- Home

- Collections

- MOODY M

- Newspaper Articles

- Newspaper Article 1991 - Settlers with an eye to business

Newspaper Article 1991 – Settlers with an eye to business

Settlers with an eye to business

Most of the earliest settlers in the Hawke’s Bay had no intention of spending their lives cutting through native bush. Capitalism, driven by Victorian business ambitions, was the real motive behind their moves in the province. MATTHEW WRIGHT reports.

AN ENDURING image of Hawke’s Bays settlement is that of the tough, resourceful colonist, ready and able to live a rugged life rewarded only by the knowledge that coming generations would reap the benefits of endless sweated labour.

Cut-out “colonial cottages” on breakfast cereal packs join museum displays of pit-sawn timber cottages in perpetuating the picture. The image of early colonists in tattered clothes, eking out an existence amid half-felled bush, remains both compelling and pervasive.

The southern half of Hawke’s Bay was settled in precisely this fashion during the 1870s. However, these pioneers did not spearhead the European invasion. Most of the earliest settlers had no intention of spending their lives cutting down native bush or, for that matter, sacrificing themselves to lives of abject squalor.

Capitalism, driven by Victorian business ambitions, was the real motive behind the very earliest settlement in Hawke’s Bay. Wealthy middle-class colonists from England sought to exploit the resources of the province. The profits they made allowed them to enjoy the comforts of large houses, refined social occasions, and all the luxuries that Victorian civilisation could provide. They exerted an overwhelming influence over political, social and economic developments.

A few people, like William Colenso, had arrived in Hawke’s Bay before many large landowners took an interest in the region. Remembered in local histories as the first pioneers, their actual influence on the subsequent social, economic and political development of the province was minimal.

Large-scale settlement began with a tide of land purchases spreading up the Wairarapa, as middle-class Victorian businessmen settling in Wellington sought a return on their capital.

Hawke’s Bay was the next obvious target. In 1840 W B Rhodes bought 1,228,000 acres in southern Hawke’s Bay for a mere £343. He was stopped by the Government from taking up his claim, but was followed by a flood of other speculators, all eager to cash in.

Many of these purchases were illegal under the Treaty of Waitangi; in 1850 the Government appointed Donald McLean to purchase land in Hawke’s Bay for the Crown. By late 1851 he had purchased nearly 700,000 acres, and by 1864 had added a further two million acres, at a cost of £180,000.

Investors were not interested in the Ninety Mile Bush that covered the south of the province. Profit could only be made quickly from the clear grasslands of central Hawke’s Bay and it was here that the first buys were made, with the aim of setting up large sheep stations.

Naturally the new land owners did not work the land themselves. Employees provided the direct muscle and farm management expertise. These people made up the first major wave of European settlers into the province. Often with plenty of capital, they saw no reason to deprive themselves of the comforts also enjoyed by their employers.

Getting sheep into the province was the first priority. Merinos had been brought across from Australia a few years before and were spreading north-ward from Wellington. In late 1848, Henry Tiffen and James Northwood hired Fred Tiffen to take 650 sheep from the Wairarapa into Northwood’s 50,000 [acre] property at Pourere [Pourerere]. The flock numbered 3000 when it arrived.

These sheep were the first of a veritable flood. In 1851 there were 10,000 sheep in the province, and by 1854 double that number grazed on the Ahuriri and Hapuku blocks alone.

By 1856 more that a third of Hawke’s Bay had been purchased by Europeans. Some 700,000 acres were occupied as sheep runs. Only 1458 acres had been fenced, but there were 130,000 sheep and nearly 4000 cattle. Wool exports were worth £20,000.

Impetus continued to come from Wellington. Some saw Hawke’s Bay as a useful place in which to invest profits from other ventures. C J Pharazyn, a Wellington shopkeeper who also owned a farm in Palliser Bay, bought land near Tikokino and left his sons as managers. John Johnston, another Wellington-based landowner, purchased Hawke’s Bay properties totalling nearly 33,000 acres.

George Hunter, who also came from Wellington, acquired Porongahau [Porangahau] Station, on the east coast of the province.

Some ventures were not successful. In the volatile economy of the early province, even the most well-organised deals occasionally went wrong. Cartwright Brown invested $21,500 in Abbotsford and Matapiro, but by 1869 had been forced to file for bankruptcy as a result of falling wool prices.

Some investors, hoping to speculate on natural resources were disappointed. Colonel G S Whitmore bought up nearly all the land between Rissington and the Kaweka ranges during the 1860s because he believed there was gold in the Kawekas. When his belief proved unfounded, he sold the land as quickly as he could.

Money lenders were quick to see openings. One of the foremost was Algernon Tollemache who, after meeting little success as a landowner in the South Island, turned to money lending as a more lucrative source of profit. He charged 10 – 15 per cent interest at first, but competition during the 1860s lowered his rates to around 7 per cent.

Shopkeepers, businessmen and other settlers flooded into the region as the new land owners spread, attracted by the chance to profit from new markets for transport, food, tools, manufactured goods, building – virtually everything needed to support a farming community.

These people helped to transform the province from a Wellington-based profit-making venture into a bustling Victorian community in its own right. Development passed beyond the stage of mere exploitation and with the growth of secondary industries new openings became available. A few businessmen, such as James Watt, actually moved to Hawke’s Bay to take better advantage of the situation.

T K Newton established the first wood [wool] broking business in Napier in 1855. Robert Holt’s timber trading business, established in 1858, expanded rapidly into general sawmilling with the growth of Napier and Hastings. William Nelson tried his hand at farming without much result, so he turned to meat processing. By 1874 there were five wool brokers in Napier.

Hawke’s Bay’s major land owners did not content themselves with mere run-holding. In an age where profits from actual farming did not meet expectations, land speculation was a temptation to which many of the enterprising Victorians succumbed.

Subdivision into town sections was the fastest way to make a quick profit. There were also benefits from having a service centre nearby. Station owners scrabbled to set up their own towns across the province. Clive was laid out as early as 1857 by Henry Tiffen on behalf of Joseph Rhodes. Havelock North followed in 1860, set up by the Chambers family, and F S Abbot [Abbott] established Waipawa, calling it Abbotsford to advertise the sale of the sections.

That year station owners set up Hampden (later Tikokino), Blackhead, Wallingford, Tuatane [Tautane], Porongahau, and Hadley near Waipawa. None came to much. The enthusiasm of run-holders to cash in farms outstripped demand. Even so, many persisted in the hope of turning a profit. H H Bridge laid out Onga Onga in 1872. Sydney Johnston of Orua Wharo established Takapau shortly afterwards.

The most successful new town was Hastings, where half a dozen landowners subdivided adjoining sections in 1873. Hastings’ success spelled the end of the line for a handful of rural service towns further south.

Victorian capitalism surged ahead at full steam during the 1870s. Property values soared. Fortunes were made. Hawke’s Bay’s wealthy continued to gain power and influence.

All was undone by the collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1879. Almost overnight many land speculators were ruined. The country was plunged into a state of acute economic depression. In Hawke’s Bay, the age of speculative investment was over.

Photo captions –

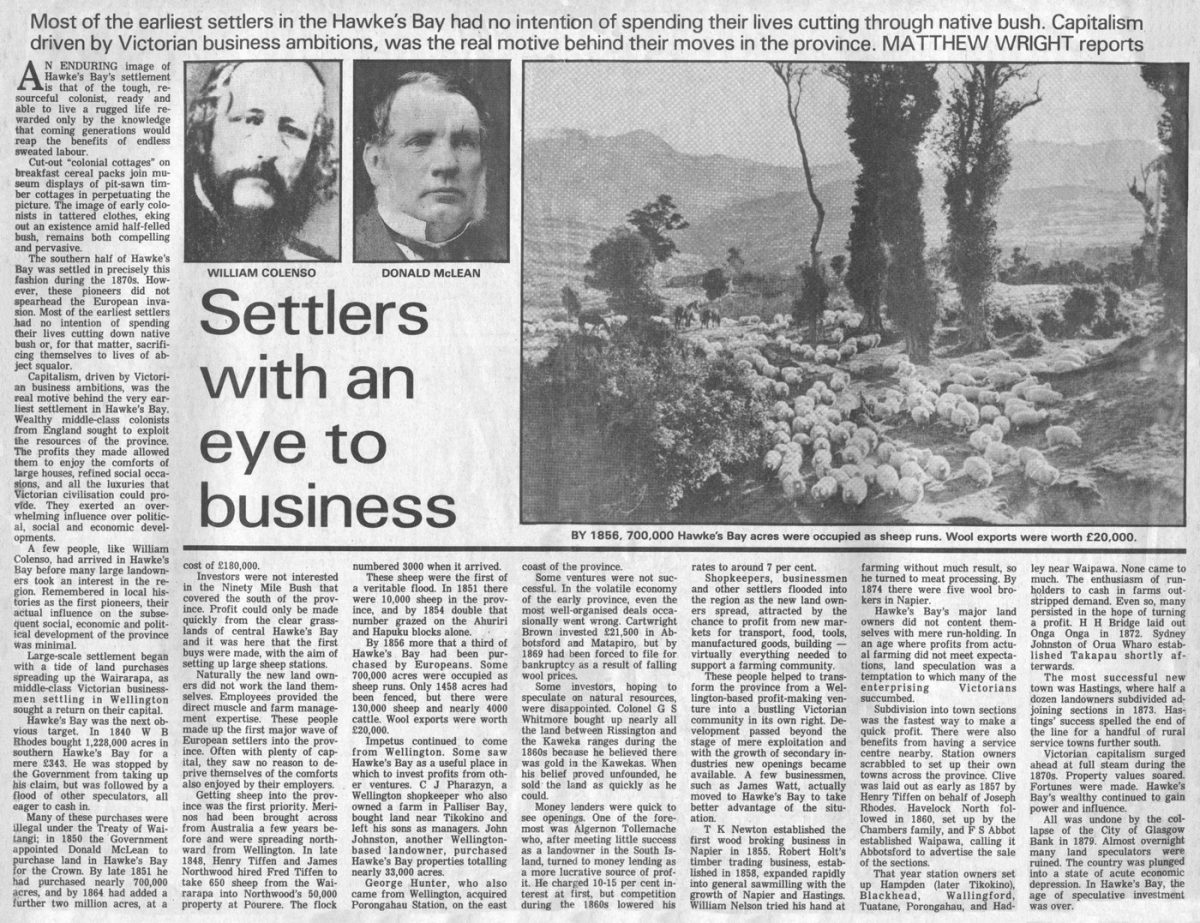

WILLIAM COLENSO

DONALD McLEAN

BY 1856, 700,000 Hawke’s Bay acres were occupied as sheep runs. Wool exports were worth £20,000.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Subjects

Format of the original

Newspaper articleDate published

26 January 1991Creator / Author

- Matthew Wright

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.