- Home

- Collections

- MASTERS RG

- Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves and Their Children

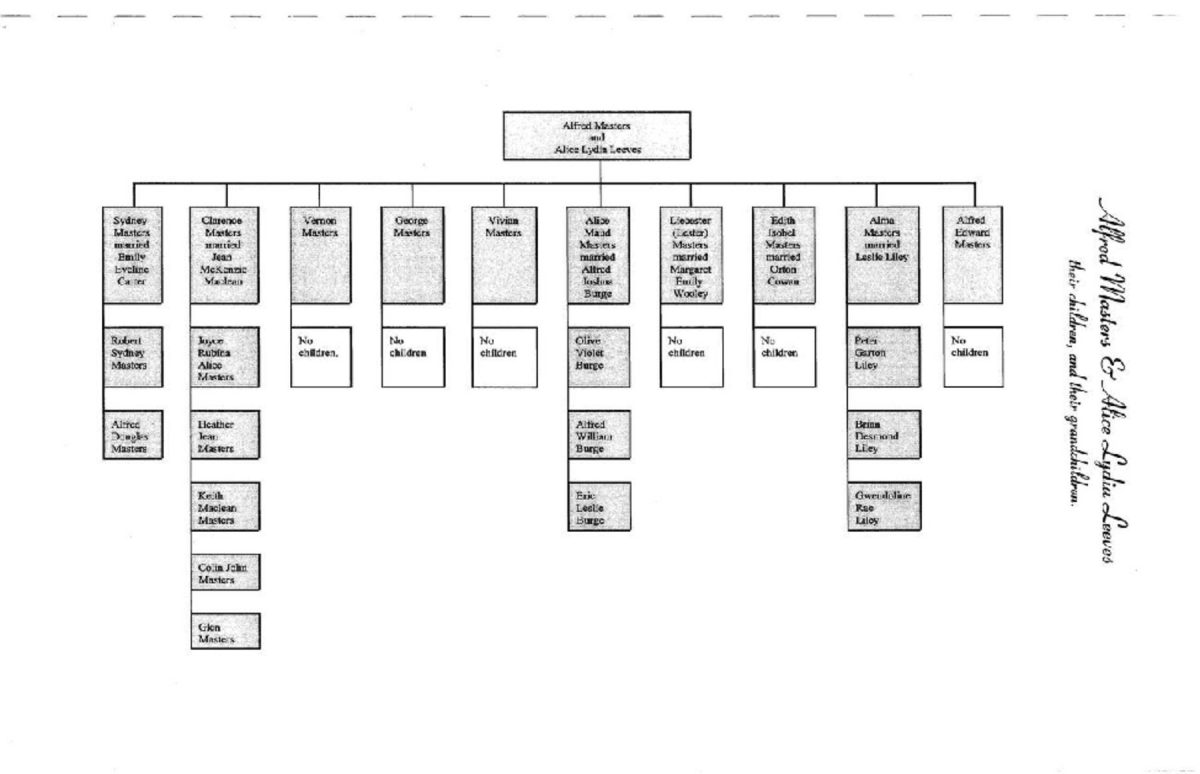

Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves and Their Children

Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves

their children, and their grandchildren

Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves

Sydney Masters married Emily Eveline Carter

Robert Sydney Masters

Alfred Douglas Masters

Clarence Masters married Jean McKenzie Maclean

Joyce Rubina Alice Masters

Heather Jean Masters

Keith Maclean Masters

Colin John Masters

Glen Masters

Vernon Masters

No children.

George Masters

No children

Vivian Masterslands for bags history

No children

Alice Maud Masters married Alfred Joshua Burge

Olive Violet Burge

Alfred William Burge

Eric Leslie Burge

Liecester [Leicester] (Lester) Masters married Margaret Emily Wooley

No children

Edith Isobel Masters married Orton Cowan

No children

Alma Masters married Leslie Liley

Peter Garton Liley

Brian Desmond Liley

Gwendoline Rae Liley

Alfred Edward Masters

No children

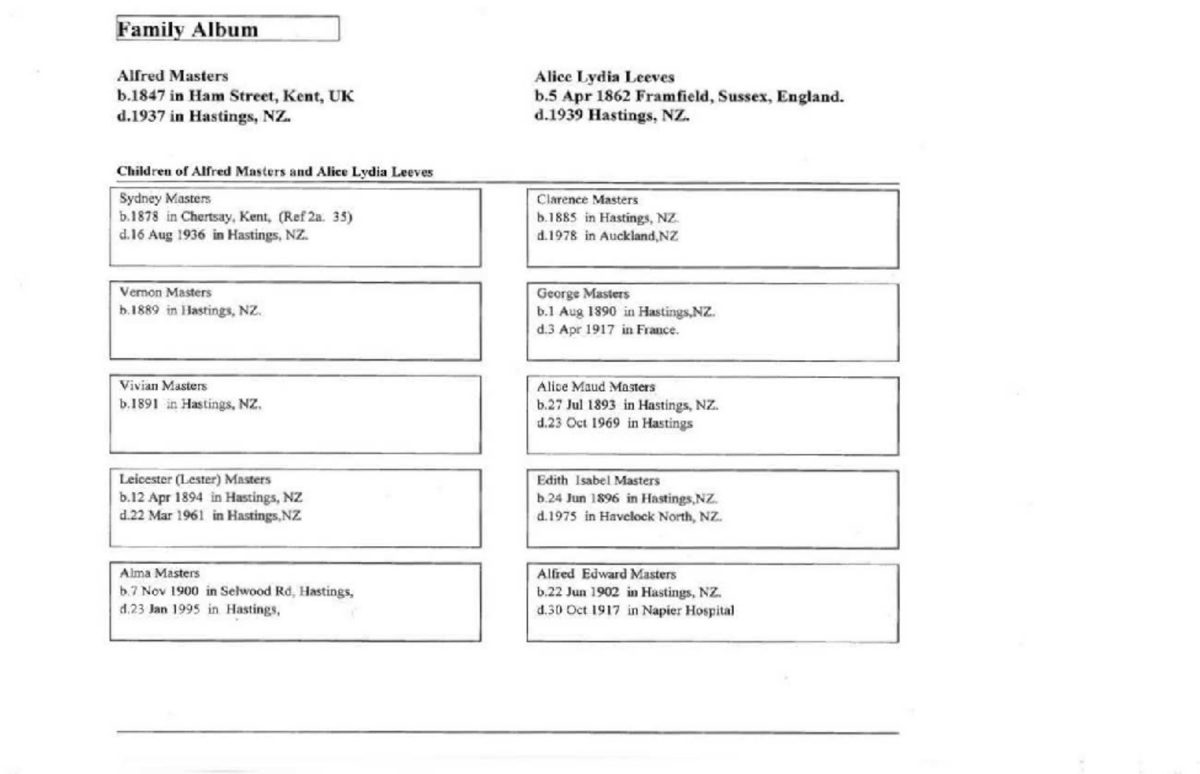

Family Album

Alfred Masters

b. 1847 in Ham Street, Kent, UK

d. 1937 in Hastings, NZ.

Alice Lydia Leeves

b. 5 Apr 1862 Framfield, Sussex, England.

d. 1939 Hastings, NZ.

Children of Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves

Sydney Masters

b. 1878 [1882?] in Chertsay, Kent, (Ref 2a. 35)

d. 16 Aug 1936 in Hastings, NZ.

Clarence Masters

b. 1885 in Hastings, NZ.

d. 1978 in Auckland, NZ

Vernon Masters

b. 1889 in Hastings, NZ.

George Masters

b. 1 Aug 1890 in Hastings, NZ.

d. 3 Apr 1917 in France.

Vivian Masters

b. 1891 in Hastings, NZ.

Alice Maud Masters

b. 27 Jul 1893 in Hastings, NZ.

d. 23 Oct 1969 in Hastings

Leicester (Lester) Masters

b. 12 Apr 1894 in Hastings, NZ

d. 22 Mar 1961 in Hastings, NZ

Edith Isabel Masters

b. 24 Jun 1896 in Hastings, NZ.

d. 1975 in Havelock North, NZ.

Alma Masters

b. 7 Nov 1900 in Selwood Rd, Hastings,

d. 23 Jan 1995 in Hastings,

Alfred Edward Masters

b. 22 Jun 1902 in Hastings, NZ.

d. 30 Oct 1917 in Napier Hospital

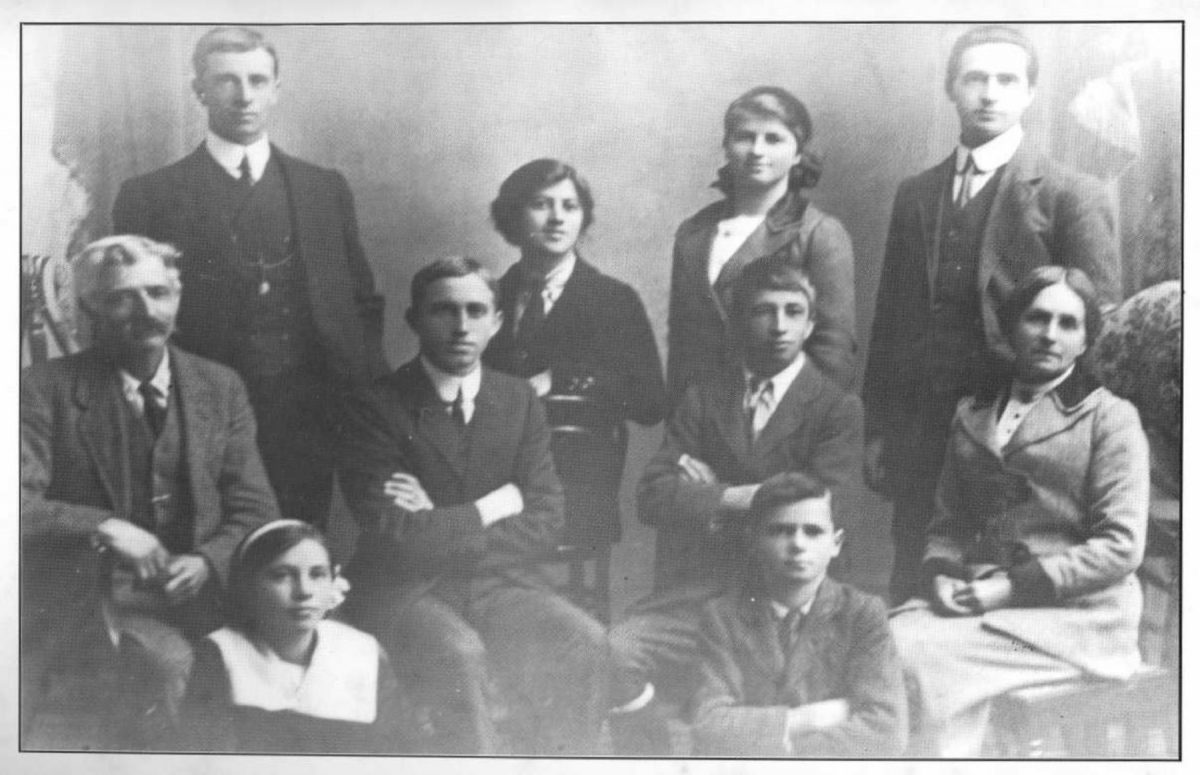

The Masters Family Group Photograph

Circa 1914

Standing in the back row:

Sydney Masters

Aged 36 years

Market Gardener/Orchardist

Alice Maud Masters

Aged 21 years.

Clerk

Edith Isobel [Isabel] Masters

Aged 18 years.

Bank Clerk

Clarence Masters

Aged 29 years.

Accountant

Seated in the middle row:

Alfred Masters

Aged 67 years.

Husband of Alice Lydia Masters.

Hop Grower.

George Masters

Aged 24 Years.

Accountancy clerk.

Leicester (Lester) Masters

Aged 20 years.

Hop Garden Worker/Shearer.

Alice Lydia Masters

Formerly Alice Lydia Leeves.

Aged 52 years.

Wife of Alfred Masters.

Seated in the front row:

Alma Masters

Aged 14 years.

Probably a pupil of Hastings High School.

Alfred Edward Masters

Aged 12 years.

Probably a pupil of Hastings Central School.

The original photograph from which this print was reproduced did not indicate the year in which it was taken. Therefore it has been necessary to estimate the year in which we see the family here. To make such an estimate, the risk of error is diminished by considering the age of the youngest in the group, and with the aid of known birth-dates, the year of the photograph and their respective ages can be calculated.

The youngest of the family is Alfred Edward Masters who is seated at the front-right of the group (as we view the photograph). The young Alfred Edward Masters in the photograph is estimated to be twelve years of age. He was born in 1902. This suggests that the year is 1914. His sister Alma who is seated in the front-left is estimated to be fourteen years of age. Alma was born in the year 1900. Again, this suggests that the year is about 1914. It is certainly not beyond the year 1914 because George Masters departed for England in 1914 to become a theological student, and later in the same year he volunteered for military service while in England. It is feasable [feasible] that the family was prompted to arrange the group photograph because of George’s plans to depart for England.

At the time of the photograph the family was living at 113 Selwood Road (now Windsor Avenue) Hastings, NZ. Their home was set about a hundred metres from the road frontage. The building featured an oblong two-storey brick structure (the dwelling) but with a hop kiln incorporated at each end.

The Masters Family Group Photograph

The photograph was taken in 1931 on the occasion of the Fiftieth Wedding Anniversary of Alfred & Alice at their home at 207 Selwood Road, Hastings. Those in the photograph are listed below from left-to-right as you view the photograph.

The arrangement of the people in the photograph is such that Alfred and Alice Masters are seated in the centre, with their children seated to the left and to the right of them. On that basis, the gentleman who is standing at the extreme right (Lester Masters, a son of Alfred & Alice Masters) should have been seated, but presumably the household was unable to produce the eighth chair needed.

The vegetation on the lap of Alma Masters and Alfred Masters is a vine of hops. Hops were grown by Alfred Masters (and later on the same property by Sydney Masters) and were a significant element in their lives.

Back row standing:

Name

Maiden name has been used in the case of married women.

Relationship

Orton Cowan

Husband of Edith Isobel Masters

Jean McKenzie Maclean

Wife of Clarence Masters

Leslie Liley

Husband of Alma Masters

Joyce Rubina Alice Masters

A daughter of Jean & Clarence Masters

Emily Eveline (Pem) Carter

Wife of Sydney Masters

Alfred Joshua (Bob) Burge

Husband of Alice Maud Masters

Leicester (Lester) Masters

A son of Alfred and Alice Masters

Middle row seated:

Name

Maiden names of daughters have been used.

Relationship

Edith Isobel [Isabel] Masters

A daughter of Alfred & Alice Masters.

Wife of Orton Cowan.

Clarence Masters

A son of Alfred & Alice Masters

Husband of Jean Masters.

Alma Masters

A daughter of Alfred & Alice Masters.

Wife of Leslie Liley.

Alfred Masters.

Husband of Alice Lydia Masters (née Leeves).

Alice Lydia Masters

Wife of Alfred Masters.

Sydney Masters

A son of Alfred & Alice Masters.

Husband of E.E. Carter

Alice Maud Masters

A daughter of Alfred & Alice Masters.

Wife of A.J. (Bob) Burge

Seated on the ground in the front row:

Name

Relationship

Alfred Douglas (Fred) Masters

A son of Sydney & Pem Masters

Eric Leslie Burge

A son of Maud & Bob Burge.

Robert Sydney Masters

A son of Sydney & Pem Masters

Peter Garton Liley

A son of Alma & Leslie Liley

Olive Violet (Molly) Burge

Only daughter of Maud & Bob Burge

Keith Maclean Masters

A son of Clarence & Jean Masters.

Colin John Masters

A son of Clarence & Jean Masters.

Alfred William (Bill) Masters Burge

A son of Maud & Bob Burge.

Page 1

Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves

and their children.

Alfred Masters was born in 1847 in a village by the name of Ham Street, which is situated about thirteen kilometres south of Ashford in the Romney Marsh area of Kent. He was the son of Frederick Masters and Sarah Masters (formerly Sarah Cobb).

Alice Lydia Leeves, who became the wife of Alfred Masters, was born 5 April 1862 in Framfield, Sussex (near Uckfield) approximately mid-way between Brighton and Tunbridge Wells. She was the daughter of Jabez Leeves, a farm labourer, and Fanny Leeves (formerly Fanny Smith).

Marriage: Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves were married in 1881 in Wilsborough, which is situated about two miles south-east of Ashford.

The Kent and Hawkes Bay connection: Alfred Masters, had worked for The Lands & Survey Dept in Kent, and is understood to have been a surveyor. Prior to migrating to New Zealand, Alfred Masters appears to have had contact with Thomas Tanner, who was a pioneer settler of the Hastings area. Tanner’s affairs were to have a pivotal effect upon Alfred Masters, and therefore his background is of some relevance here.

Thomas Tanner, born 1830, had migrated to New Zealand in 1849 on the vessel Larkins. Tanner purchased large tracts of land from the Maoris, and became embroiled in disputes regarding the legitimacy of some of the purchases. Tanner had borrowed heavily from The Bank of New South Wales and from The Northern Investment Company during his expansionary phase. The heavy borrowing coupled with inadequate returns resulted in Tanner falling into arrears with interest payments. The Riverslea Block, comprising 5,332 acres (2,158 hectares) was progressively subdivided in 1879, 1885, and 1889, thus enabling portions to be sold to settle debt arrears. Around 1882 Tanner had developed a block in hops, and about 1883 he had a financially disastrous attempt to export hops. Also In 1883, Alfred Masters arrived as a new immigrant to manage the hop gardens. Tanner’s financial problems were compounded in 1885 when a heavy infestation of Red Spider (Red Mite) ruined the vines and the year’s crop of hops. By now he owed his lenders £80,000. Tanner’s desire to ease his escalating financial problems, and his manager’s interest in acquiring property, resulted the sale of 100 acres, which incorporated the hop gardens, to Alfred Masters.

The migration: In the year 1883 the family of Alfred Masters, Alice Lydia Masters, and their 15 month old son Sydney Masters, migrated from the village of Ham Street, Kent, England.

New Zealand records of assisted immigrants who sailed to New Zealand in 1883 show Alfred Masters, whose occupation is recorded as shepherd, and his age (erroneously) as 34 years. It is doubtful that Alfred masters was ever a shepherd, and it is thought that he had stated his occupation as shepherd to improve his chances of becoming an assisted immigrant under the scheme then applied by the government of New Zealand. The same entry in the shipping record also shows Alice Lydia Masters aged 22 years, and their son Sydney aged 15 months, as having sailed from London on 29 December 1883 on the vessel S. S. British Queen. The vessel reached Wellington, New Zealand on 17 February 1884. A journey of fifty days. The

Page 2

ship’s migrant register for the journey vaguely scheduled its ports of destination as “Wellington, Canterbury, and small ports west”.

The ship carried a significant contingent of migrants who were listed as destined for Hawkes Bay, but it would appear that the S. S. British Queen did not convey them between Wellington and Napier. An abbreviated record in the Napier Museum shows that Alfred Masters, Alice Lydia Masters, and their son Sydney Masters travelled to Napier on the Southern Cross on 20 February 1883. It is not clear whether the 20th February was the date on which the vessel departed Wellington, or the date on which it arrived in Napier.

The fare (in regard to the Masters family) from England to New Zealand was subsidised by the Government under the Public Works and Immigration Act 1870, commonly referred to as the Vogal [Vogel] Scheme. The total fare was £39-0-0. Alfred Masters paid £5-0-0 in London, and the balance of £34-0-0 was paid by the New Zealand Government. On the voyage, the S. S. British Queen carried an assortment of migrants, most of whom were financially assisted. There were: 163 English, 72 Irish, 19 Scotts, 3 Germans, 1 Swede, 1 Dane, 1 French, 1 Italian.

Brother of Alfred Masters: On the same voyage of the S. S. British Queen was another Masters family who also emanated from Kent. The other Masters family was comprised of: Edward Masters, shepherd, aged 31 years; Catherine Masters aged 26 years; and children: Catherine aged 6 years; Alfred Masters aged 4 years, and Evelyn an infant. This family was also among migrants destined for Hawkes Bay. Edward Masters first appears on the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll in 1893 as a labourer, and later (variously) as labourer, or rabbiter. Edward Masters was a brother of Alfred Masters. The brother Alfred is not to be confused with infant son of Edward Masters who bore the same name. Edward Masters’ infant daughter Evelyn was to later marry Steven Jarvis, and their children (John Jarvis and Bundy Jarvis) were to own and operate an orchard in Jarvis Road, Twyford.

Employment: As mentioned earlier, Alfred Masters’ first employer was Thomas Tanner who had, among other properties, a block of about 100 acres [40 Ha] on the northern side of the Hastings – Havelock Road and which extended back from the road for ten chains [about 201 metres], between Selwood Road [renamed Windsor Avenue] and St Georges Road.

The Hop Garden Property: Thomas Tanner established the Riverslea hop gardens on the 100 acre property in Hastings about 1882 -1883 but appears to have used only 35 acres (14 hectares) for hop growing. The hop kilns (oast houses) had been built by Tommy Tanner from heart native timbers that came from Tanner’s own saw mill in the bush at Maungateretere [Mangateretere], and built of bricks from Fulford’s brick kiln at Havelock north. A hop press was also installed. One E.J. Whibley appears to have performed in a management role for Tanner during this phase. Establishment costs are recorded at £120-0-0 per acre ($296.00 per hectare) and as such it was an expensive venture to establish. For comparison purposes, £120-0-0 equated to a year’s income of a well paid skilled labourer.

The oak trees that still stand (in 1997) on the properties along the northern side of the Hastings-Havelock North road were planted by (or for) Tommy Tanner during that era.

From around 1885 when the hop plants were producing fully, 250 hop pickers were required. Some of the employees camped on the property, and others, including women and children,

Page 3

were transported to the property daily by horse drawn coach. Because of the contribution of children to the hop picking, and the significant way in which they augmented household income, summer schools did not re-open until late March.

The cooling and storage floors of the hop kiln building were used for social events, the most important of which was the hop pickers’ annual ball held at the close of each season.

Tanner sent a bale of hops to the Indian and Colonial Exhibition in 1887, and were said to compare favourably with the best of hops produced in Kent.

Tanner got into financial difficulties, and as a temporary measure, the property was taken over by a syndicate (presumably lenders or acting for lenders). By now Alfred Masters was managing the property, and the syndicate then leased the property to Alfred Masters, and later the property was sold by the syndicate to Alfred Masters.

Alfred Masters had converted the central portion of the hop kiln building into accommodation which his family used for twenty years until 1913 (at which time a home was built in Selwood Road for the family). The main access to the property was from 113 Selwood Road, and it was some two hundred yards from (and through) this point of access that the two hop kilns were situated. The two hop kilns were positioned at each end of a long two-storied house in which the Masters family were to live until 1913.

Hop Growing: The hops were grown up 5-6 six metre Manuka poles which had the base end sharpened, dipped in tar to preserve the timber, and imbedded into the [into the] ground in a similar manner to a fence post. The picking season became a labour-intensive operation. Families of seasonal workers camped in tents on the property, and entire families would become involved in the work. Hops were picked into hessian pokes [ten bushel bags]. Each hop picker would have his poke of hops measured by a bushel [about 20 kg] container, and would be paid according to the bushels picked. The hops then went by dray [a heavy-duty two-wheeled horse drawn vehicle] to one of the kilns. The kilns were for drying the hops. The kiln itself was a two-metre high raised platform with a base which was comprised of slats of spaced timber. The slats were covered with a large (expensive) horse-hair mat. A fire was lit underneath, and hops were spread over the mat. At the Masters hop kiln, the dryer was a person by the name of William Crawford. The dryer held a very responsible position on the property during the season. He tended the kiln fire, turned the hops on the drying floor at the correct times, and ensured that the correct temperatures were maintained during the various stages of the process. He made the decision as to when one batch of hops was taken off and another was put on. William was very fussy about his responsibilities and refused admittance to almost everyone while drying was in progress. Lester Masters described him as a nuggety little Kentish man with fierce looks and gruff manner. The demeanour was a facade to spare him any unwelcome intrusions or interference. His area of operation was out of bounds to children at picking time. If any were to venture that way, William Crawford would address them loudly, but would soon reveal his gentler nature by inviting them to have a look while he stocked up the kiln fire. Then he would hand out confectionery or nuts. Sometimes he would hand out potatoes that had been baked on the hot bricks. The baked potatoes would be sliced with a knife, and liberally buttered and sprinkled with salt and pepper.

After the hops were dried, they were pressed and packed, and sold under the brand name of Riverslea Hops. The name Riverslea was borrowed from the district in which the hop gardens

Page 4

were situated. The hops were principally sold to the Sunshine Brewery Napier, run by Jack Stevens. Some were exported to London, and some were sold locally in half-pound and one-pound packets through local stores for home brewing. Each packet was printed with the following home brew recipe:

Boil six gallons of water, then add 1/2 pound of hops and boil for one hour. Now add six pounds of sugar and boil for half an hour, strain, and when blood-warm put in a cup of brown sugar, the whites of two eggs, and half a pint of yeast. Let ferment for 30 hours, and then put into a wooden keg, leaving the bung out. when well fermented, bung tight. This beer is fit for use in about twelve hours.

Apart from William Crawford the hop dryer, there were other characters who worked at the hop gardens. Mr Piper, old Jim Brown, and Billy Spud. Mr Piper was a Crimean War [1841] veteran who had fought in the battle of Alma. On the slightest provocation he would give a vivid account of it. On one occasion Mr Piper accompanied Alfred Masters to Napier to collect cash from the bank. The cash was to be used to pay employees at the conclusion of the harvest. To a complete stranger sitting alongside in the railway carriage on the return journey, Mr Piper confided that “although it did not do to talk to strangers of money matters, it might surprise him to know that the little brown bag alongside his mate was full to the brim with gold and silver coins.” To Alfred Masters, the custodian of the bag, it was an unwelcome disclosure.

Old Jim Brown was a very big man with a squeaky voice. He lived alone in a cottage on his own section near the Oast House. Jim refused to pay rates, and he refused to appear in Court for the non-payment of them. He contended that by doing so he would be helping to pay white collared men to occupy easy jobs.

Billy Spud acquired his name because of his ability to dig potatoes. However, according to Lester Masters, Billy Spud was not so well endowed when it came to reasoning powers. Billy the Spud could get himself into needless difficulty with the greatest of ease.

In the early 1900s, the drain (the Makirikiri Creek which drained into the Southland Drain) that served the gardens became blocked downstream from the property. The blockage caused flood damage to the hops, and in 1894 Alfred Masters brought a civil action against the Borough Council for damages. It was the opinion of Alfred Masters that the Borough Council was responsible for keeping the drains clear and that through the Council’s failure to do so had contributed to the circumstances that had resulted in the damage to the hop vines. Alfred Masters won his case in the Magistrate’ Court but lost it again in an appeal case brought by the Borough Council in the Supreme Court. His solicitor, David Scannell, expressed the View that Alfred Masters had a case that could be taken to the Privy Council [the next level in the court system]. However, Alfred Masters considered that he had spent enough on legal fees and let the matter lapse.

Alfred Masters was awarded a Gold Medal for his hops at the Christchurch Exhibition of 1910. In the early years Alfred Masters shipped some of the hops to the London market.

The area occupied by the hop garden was later reduced to about eight acres in the vicinity of where Appledore Orchard stands (since owned successively by Sydney Masters, Alfred Douglas Masters, and Anthony Harold Masters).

Page 5

Reminiscences: Not long after arriving at the property, Alice Masters was astonished to see deer in the hop gardens. Two years later in 1886, they heard loud explosions. Because a Russian invasion was regarded as imminent, the explosions were presumed to have come from a Russian fleet bombarding the coast. Several days later, news reached Hastings of the Tarawera eruptions, and the cause of the explosions was correctly explained.

The Electoral Rolls: When gathering information on the Masters family, it was useful to search the Electoral Rolls. These provided a regularly spaced formal record of where the family was located at a particular time and the nature of Alfred Masters’ employment. These served to reinforce, or occasionally correct, anecdotal information.

The record of Births, Deaths, and Marriages has also been the source of some of the information used in this record.

The 1887, 1890, and 1893 Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll records show:

Alfred Masters, Hastings, Labourer.

In 1885 their second son Clarence was born.

In 1889 Alfred Masters purchased the Riverslea gardens from Thomas Tanner. The purchase included the two oast houses (hop kilns) and the living quarters within the same building construction.

In 1889 Vernon Masters was born. Vernon was to die as a toddler.

In 1890, George Masters was born.

In 1891 Vivian Masters was born. Vivian was to die as a toddler.

On 27 July, 1893 their daughter Alice Maud Masters was born.

In 1894, their son Leicester (Lester) Masters was born. Although registered as Leicester, the name was informally spelled as Lester in most records.

In 1896 their Daughter Edith Isobel Masters was born.

The 1896, 1897, 1900, 1902 Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows:

Alfred Masters, Hastings, Hop Farmer.

Alice Lydia Masters, Hastings, Domestic Duties.

In 1897 the Heretaunga Plains flooded and some families were driven from their homes. The top floors of the Oast House were used as a dry refuge by many of the flood victims. It was during this flood that Sydney Masters rowed a boat from the Selwood Road property to central Hastings without grounding it.

Children in those days did not have bicycles and most of their local excursions had to be undertaken on foot. Anything that made the task easier found appeal. One such ploy was to grasp the rear of a horse drawn cart or dray for a tow, or to secretly climb on board. Sydney Masters once climbed on board the rear of a butcher’s cart and was confronted by the sight of a pile of sausages. That gave him something to think about as they progressed along the road. Being a boy, and being fond of sausages, he seised [seized] a sausage and proceeded to slip off the rear of the cart with it. However, the sausage proved to be the first in a string of sausages. The butcher, who heard suspicious noises, turned to look behind. He saw a boy departing with a couple of metres of sausages trailing behind him. The cart was stopped, and the butcher gave chase, but Sydney proved to be a little more athletic than the butcher. Sydney headed through a plantation and then made his way for a shack in St Aubyn Street that was occupied by a bachelor acquaintance by the name of Geezer Smith. Geezer Smith was a former convict from Tasmania and obviously had little compunction about giving shelter to young Sydney and his string of sausages. A frying pan was produced and a hearty meal followed.

Page 6

On 17 [7] November 1900, their daughter Alma Masters was born.

Also about 1900, Sydney Masters was enrolled at Central School Hastings. He had vivid memories of negotiating a swamp with ducks on it. That swamp was where the Hawkes Bay Electric Power Board offices were later constructed in Heretaunga Street.

“Granny Masters ” (Alice Lydia Leeves) was a person who was fond of domestic activities that gave her a chance to work outdoors. Given the size of her family, her indoor responsibilities would have been very demanding, and some relief from them would have inevitably been welcome. She was reputably not a fussy housekeeper, but was particularly skilled in the craft of crochet, and would seize opportunities to work at the craft. Apart from a wide range of small items produced in fine white lace, she would crochet pillow-slips and bed covers. Such items were a major undertaking. Evenings in the lounge were an obvious time to do crochet work, but she would also sit at the dinner table (during the after-dinner conversation at the table) and work assiduously at the craft.

In 1902, Sydney Masters [at the age of 24 years] is shown on military records as having joined a New Zealand contingent of troops which eventually departed to the war in South Africa (The Boer War). Sydney Masters returned from the Boer War and lived in Hastings.

In 1902 their son Alfred Edward Masters was born.

The 1903 Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll reference to the family is unchanged (except that the occupation of Alfred Masters is simply changed from Hop Farmer to Hop Grower).

The hop picking season in March each year was an important event for the families that would avail of the employment (and consequent income). Because entire families would camp on the property for the duration of the hop picking, the Hastings District School would close for several weeks during March until the picking was finished.

The 1908 Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows:

Alfred Masters, Hastings, Hop Grower.

Alice Lydia Masters, Hastings, married.

Sydney Masters, Warren Street, Hastings, Gardener.

In 1913, the family moved into a new home in Selwood Road.

In 1911 and 1914, more of the family’s names appear on the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll:

Alfred Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Hop Grower,

Alice Lydia Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Married.

Sydney Masters, St Andrews Street, Hastings, Gardener. [A new address]

George Masters, 113 Selwood Road, Hastings, Clerk. [The address of his parents]

Clarence Masters, 113 Selwood Road, Hastings, Clerk. [The address of his parents]

In 1916, imported Tasmanian hops were cheaper, and new stock was needed at the Riverslea hop gardens if it were to continue production. It was decided to cease hop production, and to convert some of the property into orchard. On Sydney Masters instructions (while he was in camp during the First World War) Lester Masters was instructed to remove the last of the hop plants.

Page 7

On 30 October 1916 Alfred Edward Masters (a son of Alfred and Alice Masters) died at the age of fifteen years.

World War I (1914-1918) period:

George Masters was engaged to marry one Violet Bargrove of Christchurch. Immediately before joining the army, George Masters was an Anglican theological student. George served as a soldier in the Galipoli [Gallipoli] campaign (western Turkey), and despite the high incidence of casualties among troops who served in the debacle, George Masters survived the experience. With ill health he was transferred back to the British encampment in Egypt, and subsequently transferred to active service in western Europe. On 1st March 1916 he was promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant. On 27th October 1916 was sent to France (initially attached to 5 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, but soon transferred to 11 Squadron). On 15th March 1917 while serving as Observer/Gunner (probably in an FE2b aircraft) he and the pilot engaged and destroyed an enemy aircraft over Bailleul, in Belgium. On 24th March 1917, as Observer/Gunner in an FE2b aircraft (No A5442) George Masters and his pilot engaged and destroyed a German Albatros D111 aircraft while over Croisilles, France. However, shortly afterwards, while still in the vicinity of Croisilles, their FEZb was damaged in air combat with another enemy aircraft was forced to crash-land. The pilot was injured, but George Masters was unhurt. On 3 April 1917, while serving as Observer/Gunner in an FE2b (No A808) over German lines, their aircraft received a direct hit from ground-to-air gun-fire. The aircraft crashed with the loss of the lives of both George Masters and the pilot E. T. C. Brandon of South Africa.

His fiance Violet Bargrove never married, and served as a church missionary in China (until the establishment of Communism in China circa 1949), and lived in retirement in Christchurch until her death at the age of about 88 years.

George Masters completed several diaries during World War One, and these provide an insight into both his personality and the events affecting him during this period. Where available, these diaries have been reproduced elsewhere in this genealogical record.

From about mid-1917, the Oast House building was used as a school for about eighteen months until the Parkvale School was opened in 1919.

In 1921, the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows:

Alfred Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Labourers’ Agent [New Occupation. Now aged 73 years]

Alice Lydia Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Married.

And their son Clarence Masters is now shown on the Taihape Electoral Roll as an accountant, resident in Taihape.

The occupation of Labourers’ Agent is understood to be the equivalent of what we currently refer to as an Employment Agency. His roll was to maintain lists of employers seeking workers, and to refer workers to them. Presumably, he received a referral commission from the employers who accepted the workers.

About 1921 Lester Masters purchased a six acre property from Alfred Joshua Burge (who had married Lester’s sister Alice Maud Masters). The property purchased by Lester fronted onto Thompson Road, Twyford (on the southern side of Thompson Road) and was situated approximately 500 metres from Twyford Road. Lester planted the orchard, and some of the original plantings of pears (Winter Cole and Winter Nellis [Nelis] varieties) remain on the property

Page 8

as productive trees now (1996).

In 1922, the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows:

Alfred Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Labourers’ Agent.

Alice Lydia Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, Married.

Sydney Masters, Havelock Road, Hastings, Gardener. [A new address]

Alma Masters, Selwood Road, Hastings, spinster.

Lester Masters, 113 Selwood Road, Hastings, farm labourer. [Refer to the substantially expanded notes on the life of Lester Masters for a insight into his activities and interests]

In 1925, Alfred Masters is still shown on the Electoral Roll as Labourers’ Agent.

In 1925, 1927, and 1930, the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows:

Alfred Masters, 207 Selwood Road, Hastings; Retired. [The address has changed from 113 Selwood Road to 207 Selwood Road, and the occupation has changed to Retired. He is now aged 78 years]. Alice Lydia Masters, 207 Selwood Road, Hastings.

Sydney Masters, Havelock Road, Hastings, Orchardist. [This orchard was later owned by his son Alfred Douglas Masters, and later again it was owned by Anthony Harold Masters]

Clarence Masters is shown on the Taihape Electoral Rolls of 1921, 1925,1927,1930,1936, as an accountant, resident in Taihape. In 1940 he shows as accountant, 12 Burgess Road, Auckland. An Auckland telephone directory of 1955 shows him as Accountant, 22 Buchanan Street, Devonport, Auckland.

In 1927 the hop kiln building and curtilage was sold to the Anglican Church and was used as the St Barnabus [Barnabas] mission hall.

In 1931, during the Hawkes Bay earthquake, the tall brick towers at each end of the building (housing the kilns and drying floors) were badly damaged. However, the building was no longer owned by the Masters family.

In 1937 Alfred Masters died, and was buried at the Hastings Cemetery (at Stortford Lodge).

In 1939, Alice Lydia Masters died, and she was also buried at the Hastings cemetery.

Commemorative Plaque: In the St Matthews Anglican Church, Hastings, on the back-rests of the pews are brass plaques (one to each pew) commemorating eminent members of the parish. Included is a plaque to Alice and Alfred Masters. When entering the main door (at the western end), the tenth pew from the door on the left of the aisle features the small plaque. The text is in the following format:

[Image]

IN MEMORY OF ALICE & ALFRED MASTERS 1848-1937

The plaque appears to have been applied as an acknowledgement to the Masters family for funds donated to the church for the installation of long pews. At a meeting of the church committee

Page 9

on 20th February 1950 a minute was recorded as follows: “Letter received from beneficiaries of the Masters Estate offering a gift of £70 from the estate towards the provision of new pews for St Matthews Church. A letter of Acceptance to be sent.

Later, a further entry records: “Masters Family Auckland: Reported that £74 has been received as donation for seating accommodation and deposited to the No 2 a/c. The Masters Family offer a sum of £700 to form a trust in assistance in educating prospective theological students of Hastings. The Vicar is to reply after consultation with the Bishop.” This trust was to become the George Masters Trust, and it still exists in 1997.

On 2/1/47 the old Oast House was the site of the wedding of Lester Masters and his Canadian bride Margaret Emily (Meg) Wooley. It was the only wedding to have taken place in the building.

In 1950, fire destroyed the wooden part of the building.

The Era: The lifetime of Alfred and Alice Masters was an era of accelerating change. During their childhood, horses were extensively used for transport and in agriculture work. However, steam power was becoming more widely used so that in the late nineteenth century (late 1800s) steam power was commonly in use in ships, railways, and traction engines, etc. When Alfred and Alice Masters and their son migrated from England, the ship on which they travelled was steam powered. Road vehicles powered by petrol or diesel engine were not a regular sighting in New Zealand until the years immediately preceding the First World War. At this stage Alfred Masters was over sixty years of age. Horse drawn vehicles were still in use at the time of his death. It has been difficult to ascertain what mode of transport the Masters household used (other than bicycles).

Alfred Masters was known to be a sociable person, and a part of his socialising included visits to a pub in Hastings. Although, as a hop grower, he had good cause to take an interest in the beer that was produced locally from his hops, he is known as one who occasionally sampled fairly generously. Such socialising could at times placed him in a condition that rendered the bike ride homeward a little hazardous. An occasional fall from his bike was a part of the price that he paid for his socialising. At least, such evidence suggests that he was well satisfied with the quality of the products made locally from his produce.

In 1886 they were residents of Hastings when it was declared a Borough and the name Hastings was formally adopted. The name Hastings had been suggested by his former employer Thomas Tanner.

Alfred Masters first appeared on the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll of 1887, but it was not until after 1893 when woman [women] were granted the right to vote that we see Alice Masters appear on the electoral roll (for the first time in 1896).

In 1898 the Old Age Pension Act was passed by Parliament. At this time New Zealand was the only country that had legislation that provided a retirement income from the Government. Alfred Masters was then 51 years of age, but it was many years before he fully retired. It was not until 1925 that the Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows his occupation as “retired ” (by then he was aged 78 years).

Page 10

They were to witness the transition from candle and gas lighting to electric lighting. Similarly, wood or coal range stoves and ovens were replaced by gas cooking appliances, and later they were to be witness to the introduction of electric cooking appliances.

Theirs was an era in which the news media was limited to a daily copy of the local newspaper. The daily newspaper was a significant element in the daily routine of most households. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s that the household radio added a further dimension to the contact with the outside world. Public entertainment was limited to theatre, a few sports such as Rugby, boxing, and horse racing, and in the 1930s cinema added to the range of choices. Television was still unheard-of in the life-time of Alfred and Alice Masters.

By comparison with what is available today, the household appliances available during their era may have seemed very limited, and home entertainment near non-existent. However, their lives were far from inactive or boring. The lack of sophisticated domestic appliances meant that a housewife was additionally busy because of the additional time that was required to accomplish quite basic chores. Alfred and Alice Masters had a large family, and that factor inevitably added to the complexity and intensity of their daily routines.

Given the achievements of Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves, it is reasonable to assume that their’s had been a home and family life in which the essentials to a healthy and comfortable existence were generally available. However, none of that was achieved without hard work, sound judgement, some sense of adventure, and a ready sense of humour to give balance to their daily lives. The Masters children all reflected those traits, and a refined but unpretentious quality demonstrated the healthy balance of their background.

Their children were all physically active and sound, and each in their own sphere of interest and activity were to become successful and interesting people. That is in itself a testimony to the achievements of Alfred and Alice Masters.

[Photo]

A.W. (Tony) Rule. 17 June 1997

Page 1

Descendant Report for: Alfred Masters

Alfred Masters (b. 1847, d. 1937, m. Alice Lydia Leeves)

Sydney Masters (b. 1878, d.1936, m. Emily Eveline (Pem) Carter)

Alfred Douglas (Fred) Masters (b. 1918, d.1984, m. Gladys Mary Young)

Pamela Jill Masters (b. 1942, m. John Montgomerie Haywood)

Christina Ann Haywood (b. 1973)

Karen Elizabeth Hayward [Haywood] (b. 1976)

Barbara Nancy Masters (b. 1945, m. Kenneth Champney Slade)

Fiona Juliette Slade (b. 1973)

Belinda Elizabeth Slade (b. 1975)

Patricia Evelyn Masters (b. 1946, m. Robert George Elliott Moore)

Melanie Sarah Moore (b. 1973)

Caroline Louise Moore (b. 1974)

Anabel Clare Moore (b. 1980)

Charlotte Mary Moore (b. 1981)

Robert Gregory (Bob) Masters (b. 1948, m. Judith Anne Vesty)

George Robert Masters (b. 1983)

Rosemary Elizabeth Masters (b. 1985)

Anthony Harold (Tony) Masters (b. 1951, m. Heather Margaret Chisholm)

Timothy Hugh Masters (b. 1976)

Amanda Anne Masters (b. 1978)

Suzanne Mary Masters (b. 1981)

Rodney Frederick Masters (b. 1985)

Kerry Douglas Masters (b. 1955, m. Sally Leeves)

Rachel Masters

Benjamin Douglas Masters (b. 1979)

Felicity Masters (b. 1981)

Hannah Lillian Masters (b. 1984)

Edward Denby Masters (b. 1985)

Robert Sydney Masters (b. 1920, d. 1941)

Clarence Masters (b. 1885, d. l978, m. Jean McKenzie Maclean)

Joyce Rubina Alice Masters (b. 1916, d. 1995, m. Samuel William Keats)

Hugh Forbes Keats (b. 1941, m. Janice Ann Scott)

Grant John Keats (b. 1966, m. Branka Injac)

Craig Alan Keats (b. 1968)

Michelle Ann Keats (b. 1972, m. Rhys Nolan Puru)

Tyler Forbes Puru (b. 1993)

Carl Mansell Puru (b. 1994)

John Maclean Keats (b. 1946, m. Brenda Rosalie Bryers)

Renee Naomi Keats (b. 1972, d. 1994)

Blair Anaru Keats (b. 1976)

Erana Danielle Keats (b. 1979)

Alan Grant Keats (b. 1949, m. Kaye Elizabeth Powell)

Damon Bryce Keats (b. 1979)

Willow-Ann Melissa Keats (b. 1981)

Laurel Ilana Keats (b. 1983)

Brook Samuel Keats (b. 1986)

Jasper Keats (b. 1989)

Heather Jean Masters (b. 1917, m. John Hayes)

Jenifer Lindsey Hayes (m. Brock)

Lianne Gail Brock (b. 1963)

Kiren Lea Brock (b. 1966)

Christina Lianne Noad (b. 1962, fath. William C. Noad)

Keith Maclean Masters (b. 1924, m. Ines Isabel Munro)

Lesley Kay Masters (b. 1954)

Page 2

Descendant Report for: Alfred Masters

Robyn Louise Masters (b. 1957, m. Rodney Keith Palmer)

Kelly Louise Palmer

Olivier Brook Palmer

Grant Maclean Masters (b. 1961, m. Lynette Ann Gaskin)

Colin John Masters (b. 1927, m. Josephine Ann Horman)

Twin infants (decd @ 1-3 days) Masters

Gregory Maclean Masters (b. 1957, m. Lynne Judith Mossiter)

Samuel John Maclean Masters (b. 1993)

James Alexander Campbell Masters (b. 1996)

Iain Alistair Campbell Masters (b. 1960)

Colin Scott Masters (b. 1962, m. Rebecca Anne Sunderland)

Georgina Alice Masters (b. 1992)

Libby Jane Masters (b. 1994)

Harry Colin Masters (b. 1995)

Glen Masters (b. 1928, d. 1931)

Vernon Masters (b. 1889)

George Masters (b. 1890, d. 1917)

Vivian Masters (b. 1891)

Alice Maud Masters (b. 1893, d. 1969, m. Alfred Joshua (Bob) Burge)

Olive Violet (Molly) Burge (b. 1918, m. Leonard William (Len) Rule)

Vernon John Rule (b. 1941, m. Jeanette Leonie Thompson)

Lianne Rule (b. 1963)

Grant Michael Rule (b. 1965, d. 1986)

Danene Rule (b. 1970)

Anthony William Rule (b. 1944, m. Glennis Margaret Kemp)

Michelle Anita Rule (b. 1968, m. David Wood)

Hayden David Wood (b. 1991)

Natasha Louise Wood (b. 1992)

Angela Lisa Rule (b. 1969)

Philip John Rule (b. 1972, d. 1992)

Lorraine Elizabeth Rule (b. 1946, m. Clive William Garland)

Christopher Aaron Garland (b. 1971)

Gavin Clive Garland (b. 1972)

Paul Michael Garland (b. 1974)

Michael Adrian Rule (b. 1947, m. Susan Margaret Thomson)

Adele Melissa Rule (b. 1976)

Melanie Jane Rule (b. 1978)

John William Rule (b. 1981)

Alfred William (Bill) Burge (b. 1920, m. Jean Hudson)

Allan Eric Burge (b. 1943, m. Gay Julie Campbell)

Sophie Dale Burge (b. 1964, m. Ian Craig Foote)

Hallam Foot [Foote] (b. 1985)

Haemia Jean Foote (b. 1986)

Caleb Foote (b. 1988)

Seth Foote (b. 1990)

Jesse Foote (b. 1992)

Miriam Reyna Foote (b. 1994)

Sheahan Foote (b. 1995)

Leam Foote (b. 1996)

Suzanne Gay Burge (b. 1965, m. Sean Michael Martin)

Daniel Elisha Martin (b. 1993)

Elya Beth Martin (b. 1994)

Ethan Thomas Martin (b. 1996)

Eric Leslie Burge (b. 1921, m. Moira Elizabeth Cassin)

Page 3

Descendant Report for: Alfred Masters

Colleen Margaret Burge (b. 1949, m. Rodney Webb)

Ashley Shane Webb (b. 1970)

Larisa Ingrid Webb (b. 1972)

Aiyana Ambra (b. 1983)

Timothy Vardon (b. 1985)

Joshua Lawrence (b. 1992)

Gary Kenneth Burge (b. 1951)

Fritha Wyn Burge

Morwenna Simone Burge

Brent William Burge (b. 1953)

Thomas James Burge (b. 1983)

Jessica Burge (b. 1985)

Richard Conrad Burge (b. 1987)

Marlene Louise Burge (b. 1955)

Gail Patricia Burge (b. 1957, m. Paterson)

Emma Jane Paterson (b. 1980)

Ann Beth Paterson (b. 1982)

Kim Francis Paterson (b. 1985)

Leicester (Lester) Masters (b. 1894, d.1961, m. Margaret Emily (Meg) Wooley)

Edith Isabel Masters (b. 1896, d.1975, m. 0rton Cowan.)

Alma Masters (b. 1900, d. 1995, m. Leslie Liley)

Brian Desmond Liley (m. Gareth Marell Jones)

Simon Liley (b. 1962, m. Raeleen Fay McLaughlin)

Jason Kerry Liley (b. 1988)

Claira May Liley (b. 1990)

Charlotte Rita Liley (b. 1996)

Joanna Kim Liley (b. 1964, m. Merrick Walter Mullooly)

Jenna Helen Marell Mullooly (b. 1988)

Luke Desmond Joseph Mullooly (b. 1991, d. 1995)

Angela Claire Liley (b. 1966)

Peter Garton Liley (b. 1929, d. 1996)

Gwendoline Rae Liley (b. 1932, m. Charles William Sheppard Couch)

Sally Linda Couch (b. 1965, m. Dean Frederick Mildenhall)

Tyler Thompson Mildenhall (b. 1996)

Philippa Sarah Couch (b. 1969)

Alfred Edward Masters (b. 1902, d. 1917)

Ancestor Report Robert Gregory (Bob) Masters

Alfred Masters

born: 1847 in Ham Street, Kent, UK

died: 1937 in Hastings, NZ.

Alice Lydia Leeves

born: 5 Apr 1862 in Framfield, Sussex, England.

died: 1939 in Hastings, NZ.

Sydney Masters

born: 1878 in Chertsay, Kent, (Ref 2a. 35)

died: 16 Aug 1936 in Hastings, NZ.

Alfred Douglas (Fred) Masters

born: 6 Nov 1918 in Hastings, NZ.

died: 18 Mar 1984 in Hastings, NZ.

Emily Eveline (Pem) Carter

born: 1880 in UK

died: 7 Oct 1962 in Melborne [Melbourne], Australia.

Robert Gregory (Bob) Masters

born: 13 Sep 1948 in Hastings, NZ.

Gladys Mary Young

born: 13 Feb 1919 in Hastings, NZ.

Page 1

Sydney Masters

(The eldest son of Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves)

Sydney Masters was born in England, and migrated to New Zealand with his parents. New Zealand records of assisted immigrants who sailed to New Zealand in 1883 show Alfred Masters, whose occupation is recorded as shepherd, and his age (erroneously) as 34 years. The same entry in the shipping record also shows Alice Lydia Masters aged 22 years, and their son Sydney aged 15 months, as having sailed from London on 29 December 1883 on the vessel S.S. British Queen. The vessel reached Wellington, New Zealand on 17 February 1884. A journey of fifty days.

The ship’s migrant register for the journey vaguely scheduled its ports of destination as “Wellington, Canterbury, and small ports west “. The ship carried a significant contingent of migrants who were listed as destined for Hawkes Bay, but it would appear that the S. S. British Queen did not convey them between Wellington and Napier. An abbreviated record in the Napier Museum shows that Alfred Masters, Alice Lydia Masters, and their son Sydney Masters travelled to Napier on the Southern Cross on 20 February 1883: It is not clear whether the 20th February was the date on which the vessel departed Wellington, or the date on which it arrived in Napier.

The fare (in regard to the Masters family) from England to New Zealand was subsidised by the Government under the Public Works and Immigration Act 1870, commonly referred to as the Vogal Scheme. The total fare was £39-0-0. Alfred Masters paid £5-0-0 in London, and the balance of £34-0-0 was paid by the New Zealand Government. On the voyage, the S. S. British Queen carried an assortment of migrants, most of whom were financially assisted. There were: 163 English, 72 Irish, 19 Scots, 3 Germans, 1 Swede, 1 Dane, 1 French, 1 Italian.

The family moved directly to Hastings to the property owned by Tommy Tanner between Selwood Road (re-named Windsor Avenue) and St Georges Road. This property was purchased from Tommy Tanner by Alfred Masters in 1889, and continued in use as a commercial hop garden.

Hastings was established in an area that featured several wetland (swampy) areas, and Sydney Masters had reflected upon his early school days by describing an occasion on which he had negotiated a swamp, complete with ducks, at the site where the Hawkes Bay Electric Power Board later stood in Heretaunga Street (between Hastings Street and Karamu Road). It is presumed that when Sydney negotiated the swamp, it was the voluntary diversion of an adventurous schoolboy rather than the normal route to be taken.

The school to which he was going is understood to be Hastings Central School situated in Karamu Road south.

Children in those days did not have bicycles and most of their local excursions had to be undertaken on foot. Anything that made the task easier found appeal. One such ploy was to

Page 2

grasp the rear of a horse drawn cart or dray for a tow, or to secretly climb on board. Sydney Masters once climbed on board the rear of a butcher’s cart and was confronted by the sight of a pile of sausages. That gave him something to think about as they progressed along the road. Being a boy, and being fond of sausages, he seised [seized] a sausage and proceeded to slip off the rear of the cart with it. However, the sausage proved to be the first in a string of sausages. The butcher, who heard suspicious noises, turned to look behind. He saw a boy departing with a couple of metres of sausages trailing behind him. The cart was stopped, and the butcher gave chase, but Sydney proved to be a little more athletic than the butcher. Sydney headed through a plantation and then made his way for a shack in St Aubyn Street that was occupied by a bachelor acquaintance by the name of Geezer Smith. Geezer Smith was a former convict from Tasmania and obviously had little compunction about giving shelter to young Sydney and his string of sausages. A frying pan was produced and a hearty meal followed.

In 1897, when a severe flood extended across much of the Heretaunga Plains (around Hastings) Sydney Masters was a teenager. He amused himself at one stage during the flood by rowing a boat from his parents’ property to what is understood to have been the vicinity of Hastings Street on the eastern boundary of the Hastings retail area, and returned to home without once grounding the dingy.

From about April 1901 until 9th April 1902, Sydney Masters had been attached to D Company of the North Island Battalion. His unit in April 1902 was the Hawkes Bay Mounted Rifles. (Personal Military No 8978.)

On 9th April 1902, while at Trentham Military Camp in the Hutt Valley, Sydney Masters enlisted for service (as a volunteer) with the Tenth Contingent for active service in South Africa in the conflict against the Boers.

His application form described him as aged 20 years (not necessarily his correct age), 5 feet, 6 inches tall (167 centremetres [centimetres] tall), weighing 9 stone, 5 pounds (59.4 kilograms), he had brown eyes, brown hair, and dark complexion. His civilian occupation was recorded as “gardener”.

Ten contingents of New Zealand Volunteer Mounted Rifles, comprising (in total) 6,500 men and 8,000 horses went to South Africa. The ninth and tenth contingents arrived a short time before the conflict ended and saw little action. On May 31st 1902 the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed by the opposing forces, and the New Zealand Tenth Contingent of Volunteer Mounted Rifles (including Private Sydney Masters) returned home.

On 31st August 1902 Private Sydney Masters was granted discharge from the army, and resumed employment on the family property in Hastings.

The 1908 Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows Sydney Masters as resident in Warren Street Hastings, and his occupation is recorded as gardener. Sydney is by now aged twenty nine years. It is unclear whether Sydney was a commercial market gardener, but he is believed to have been comprehensively involved in the various seasonal commitments associated with the growing of hops on the property (hop garden) owned by his father.

Page 3

Sydney Masters commenced planting the orchard on the property in 1905 – 1908.

In the 1911 and 1914 Hawkes Bay Electoral Rolls he appears as resident in St Andrews Street Hastings, and his occupation continued to be recorded as gardener. Sydney’s younger brothers George and Clarence are both shown on the Electoral Roll as employed as clerks, and both entries feature the address of 113 Selwood Road, Hastings (also the address of their parents).

In 1916, at the age of thirty seven years, Sydney Masters was again in the army. However, no reference has been traced to his having served abroad during the First World War, and presumably Sydney served as an Army Instructor during this period.

It was while he was in the army in 1916 that he gave his younger brother, Lester Masters, instructions that the hop plants at the Selwood Road property were to be up-rooted. This implies two things: Firstly, that Sydney was the person who was principally responsible for the management of the hop garden, and secondly, that Lester Masters was at that time an employee on the property.

In 1916, Sydney Masters appears on the National Archive records as having married (ref No 3748) to Emily Eveline Carter (known as Pem).

In 1922, The Hawkes Bay Electoral Roll shows Sydney Masters as resident in Havelock Road. The property then occupied by Sydney was a part of the original tract of land which his father had purchased from Tommy Tanner. However, the block occupied by Sydney was planted in orchard. [This property was later owned or operated in succession by his sons Robert Sydney Masters, Alfred (Fred) Douglas Masters, and Anthony Harold Masters]

Sydney’s brother Lester Masters was also orcharding at this time. Lester had, about 1921, purchased a six acre block in Twyford (about eight kilometres west of Hastings) and had developed it as an orchard.

Sydney Masters married Emily Eveline Carter (known affectionately by relations as Pem). They had two sons: Robert Sydney Masters and Alfred Douglas Masters.

Sydney Masters was to die on 16 August 1936 at (or about) the age of fifty seven years. The orchard was operated by his sons. However his son Robert Sydney Masters flew for the Royal Air Force during World War II, and lost his life in combat in 1941 while flying in Tunisia, during the North African campaign.

The orchard was then operated by Alfred Douglas Masters (aged 23 years) for his father’s estate. Alfred Douglas Masters was to later own the property.

This group are, from left to right (as YOU view the photo) Clarence Masters, Alice Maud Burge (née Masters), Francis Thompson and his new wife Edith Isabel Thompson (née Masters), Alma Liley (née Masters), Leicester (Lester) Masters. They are at 918 west, Heretaunga Street, Hastings, the home Alice Maud Burge.

Page 1

Clarence Masters

(Son of Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves)

Clarence Masters was the second son of Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves. Clarence was the first of the children to be born in New Zealand, and the event occurred in Hastings in 1885 and about two years after the arrival in New Zealand of his parents and his older brother Sydney.

Clarence spent his childhood at the property in Selwood Road (re-named Windsor Avenue) Hastings.

As a six-year old child, Clarence was involved in an accident that resulted in the loss of a leg. He is understood to have been amusing himself by clinging to the rear of a dray (a heavy duty two wheeled horse drawn vehicle). The dray driver had halted the dray, and unaware of Clarence’s presence, proceeded to un-latch the mechanism that would enable the tray of the dray to tilt to the rear and allow its load to slide from it. When the tray tipped, Clarence’s leg became trapped between the underside of the tray and the ground. The severity of the injury necessitated amputation of the leg. It was a very sad end to what had been a little boy’s moment of fun.

Although Clarence regained the ability to walk through the use of a peg-leg, it remained a restrictive disability, and one that was to eventually influence the choice of his occupation. He was encouraged to align his schooling to a sedentary occupation, and to gain academic qualifications. He chose accountancy.

Initially, he was employed by George Roach who owned a retail shop at the corner of Heretaunga Street and King Street Hastings (south-eastern corner). Roaches retailed groceries, Manchester, ladies’ wear, men’s wear, fabrics, and shoes. Roaches also had branches at Parongahau [Porongahau], Havelock North, and at the corner of Warren Street and Heretaunga Street Hastings.

George Roach had indicated to Clarence Masters that he found appeal in the idea of bringing Clarence into the business as a partner. The idea also appealed to Clarence, but it appears that George Roach procrastinated with forming suWch a partnership. Clarence had a healthy ambition to progress occupationally, and was not prepared to wait interminably for Roach to decide whether or not he was going to form a partnership. Clarence considered that with his accountancy qualifications and experience, he was in a position to establish an accountancy practice, and by doing so could satisfy his aspirations for a more challenging occupation. He ended his association with Roaches around the period 1814-1921. He appears for the first time on the Taihape Electoral Roll, as an Accountant, in 1921.

During the time in which Clarence was in practice in Taihape, he was concurrently secretary for the dairy company at Utiku (about eight kilometres south of Taihape).

Clarence appears to have married around 1920. His bride was Jean Maclean who was born W

Page 2

on 27 September 1889 in Dornock in north-eastern Scotland, and later moved with her family [to] Cromarty (at the northern tip of the Black Isle, overlooking the channel between the Moray Firth and Cromarty Firth.) Jean had a sister and two brothers. Her father was a sea captain who spent many years sailing a merchant vessel to and from the Baltic. Jean Maclean migrated to New Zealand at the age of eighteen years (about 1907) with an arrangement to be housekeeper for an uncle in Hastings, NZ. The arrangement was for the uncle to send her home at the end of the two years, but he did not do so. As a consequence, Jean remained in Hastings and in due course met Clarence Masters, and their marriage ensued.

Their family of four children: Joyce, Heather, Colin, and Keith are understood to have been all born in Taihape, and to have attended schools there. However, Clarence and Jean considered that the formal education of their children would be better served if they were to all move to Auckland. In 1938, when Clarence was fifty three years of age, the family moved to 12 Burgess Road, Auckland. It was also the year in which Clarence and Jean undertook a trip to England and Scotland. They were to later Wmove to 22 Buchanan Street, Devonport, Auckland.

Despite having to contend with the physical limitations imposed by an artificial leg, Clarence was an energetic person. He moved with vigour, and he thought with vigour. His speech was lively, and he frequently exhibited the lively sense of humour which was also characterised his brothers and sisters. While he appears to have inherited, or learned by observation, his father’s courageous and enterprising approach to life, Clarence was far from being an exclusively serious person. He was in fact capable of astonishing and amusing his company by spontaneously engaging in fun activities which might normally be regarded as the preserve of much younger people. For example, about 1960 while visiting a niece (Olive Violet Burge) in Twyford near Hastings, the neighbouring (Burge) children, who were also related, arrived in a whirl of activity with a home-made children’s trolley. The trolley was constructed of pram wheels (and axels [axles]) mounted at each end of a plank of timber. Seating was by way of a wooden box nailed to the rear end of the trolley, and padded with a jute sack. To provide steering, lengths of chord extended from the front swivelling axel [axle], to be clasped and pulled left or right as required to achieve a left or right turn. Clarence immediately recognised the contrivance as the source of some practical fun. Despite his age (about 75 years) he disengaged his conversation with his hosts and fellow guests, and recruited the services of the Burge children to give him a ride on their trolley. Clarence was soon securely in the seat with steering ropes firmly in hand. With Colleen, Gary and Brent Burge pushing from behind, Clarence embarked upon a boisterous and noisy hundred meters escapade along Jarvis Road (and back to his starting point).

Clarence must be regarded as a very successful businessman and family man, and a person with an endearing and engaging personality.

Page 1

Alice Maud Masters

(The first daughter of Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves)

Alice Maud Masters (known as Maud) was born 27 July 1893 at the residence which was incorporated at the hop kiln building at 113 Selwood Road (re-named Windsor Avenue) Hastings.

Schooling: Maud attended primary school at Hastings Central School in Karamu Road Hastings, and on 3rd February 1908 at the age of 14½ years enroled [enrolled] at the Hastings High School in Karamu Road. [The high-school later became Hastings Boys High School] Maud completed two years at High School, and on 17th December 1909 at the age of 15 years and 5 months she left school to begin “home duties ”.

New Masters’ Home: In 1913 the Masters family vacated their residence at the hop kiln where they had lived for some twenty nine years, and moved into a new home in Selwood Road with a street frontage. Maud was by this time about twenty years of age, and her father and mother sixty five years and fifty one years of age respectively. It appears that her father was still growing hops on the Selwood property, but by this stage assisted by their eldest son Sydney.

Employment: Upon completion of her schooling, Maud was employed at Roach’s of Hastings. Roach’s retailed groceries, linen goods, cotton goods, fabrics, ladies’ wear, men’s wear, and shoes. Her employment with Roach’s appears to coincide with her brother Clarence’s employment with the firm. She was also employed by Sommersill’s General Carrying business at Ongaonga (west of Waipawa). Maud was also employed in Hastings with the solicitors Hallet O’Dowd in Queen Street. Her employment in each instance appears to have been in a clerical role, and all occurred prior to her marriage to Alfred Joshua Burge circa 1916.

The Burge family: From about 1908, the Burge family had lived in Louis [Louie] Street, Hastings, where they had established an orchard and had built a family home (which is still standing now in 1996). This property was some five hundred metres from where the Masters family were living in Selwood Road. Alfred Joshua Burge (always referred to as Bob) had been variously employed as a home decorator, a bush feller in the Tokomaru district, a farm hand, and self-employed in the supply of flax to a Tokomaru flax mill for £5-0-0 per ton during his former years in Tokomaru.

Farm Properties: At the time of their marriage, Alfred Joshua Burge owned a cropping property in partnership with an acquaintance David Patrick Henry Thompson. David Thompson was also a former resident of Tokomaru. The partnership property was in Twyford Road, Twyford. That was sold around 1919, and Alfred Joshua Burge then purchased a farm of about 36 acres in Jarvis Road Twyford. (David Thompson then also purchased a property in Jarvis Road). The couple (Alice Maud Burge (née Masters) & Alfred Joshua Burge) moved onto the new farm property about 1920, but lived in temporary quarters constructed within or adjacent to an existing shed (which still stands in 1996). During 1920-1921 a new three- bedroom home was constructed with a frontage onto Jarvis Road (also still standing in 1996,

Page 2

but modified),

Dairy Farming: The farm in Jarvis Road Twyford was principally used for dairying. For the era, the dairy herd was of average or small size with about twenty five productive cows. (Fifty years later an average small size herd comprises about 150 cows.) The milk was separated on the farm. This was a process by which the milk was run through a Separator machine to segregate the cream from the skimmed-milk. The cream was sent to the dairy factory at Stortford Lodge, Hastings, and the skimmed milk was fed to pigs.

Winter feed supplements were produced by way of hay and silage, and a 2½ Ha paddock was permanently in lucerne. Lucerne was drought-resistant, and was particularly significant as a stock feed during drought conditions.

Grass Seed: An important adjunct to the dairying operation was a commercial crop of rye-grass grown annually for seed. The farm produced rye of a particularly high standard. It was largely free of other types of grass seed, and was well regarded by the seed merchants in Hastings. Alfred Joshua Burge had commented to me that he had received very good prices for his rye grass seed.

Farm Machinery: Draft horses were used for hauling farm implements and the farm sledge. Seed thrashing was undertaken by a contractor with a seed-mill powered by a Traction Engine (a steam-engined tractor).

Although petrol engined tractors existed, they had not completely displaced draught horses (or Traction Engines) until several years after the Second World War. Farm transport requirements were served by either the traditional horse-drawn farm sledge or a dray. A dray was a heavy duty two wheeled horse drawn vehicle. Both of these latter items were used by A.J. (Bob) Burge until retirement in 1953.

The Orchard: Progressively during the first fifteen years of occupation of the farm, the southwestern side of the property was converted into approximately five acres (2½ Ha) of orchard. The trees included Winter Nellis [Nelis] pears, Delicious apples, Sturmer Pippin apples, Dougherty apples, Ballarat apples, and Granny Smith apples. Golden Queen peaches, Sultan plums, Coxes Orange Pippin apples, and Santa Rosa plums.

Before the Second World War, all fruit was sold to merchants who would call at the orchard properties and offer a price for the fruit. A price and quantity would be agreed between the orchardist and the merchant. Alfred Joshua Burge generally dealt through two particular merchants, but others would also appear on the property and enter into deals. An occasional rogue merchant would take fruit and not pay for it on the pretext that he couldn’t sell the consignment. During the Second World War fruit was almost exclusively supplied to an American Armed Services ordinance organisation that was required to supply the American Armed Services based in the Pacific. The American ordinance organisation was a reliable payer, and an effective means through which growers could market their fruit. After the war, the Internal Marketing Division replaced the American Ordinance buyers, and that in turn was replaced by the NZ Apple & Pear Marking [Marketing] Board.

Page 3

Family Transport: Perhaps of minor passing interest is the family transport used during the years when Alfred Joshua Burge and Alice Maud Masters were at Twyford: Until about 1926 the family used a Trap which was a light two-wheeled horse drawn vehicle pulled by one horse between shafts. A Trap had no canopy. It seated two people in the forward-facing seat. A storage tray was situated beneath the seat and had a similar function to the modern car boot. Their first motorised family transport was canvas-top Chrysler car of mid-late 1920s Vintage. This was followed by a 1938 Chevrolet car, and a 1953 Morris Oxford car.

Clubs & Societies: Alice Maud Masters became involved with the Hastings Red Cross Society during the Second World War, and continued her association with the Society until the mid-1950s. She was also involved with the Twyford Country Women’s Institute, and served as its president for several years. Alice Maud Masters was also involved with the Heretaunga Bowling Club for many years, and was president of the club for three terms. Her association with the bowling club involved occasional travel to other towns during tournaments or in attending to administrative matters.

Retirement and Travel: The year 1953 was a year of considerable change. It was the year in which they retired. A new retirement home was built at 918 West, Heretaunga Street, Hastings. Bob and Maud also undertook an overseas trip in 1953, and sailed by Passenger Liner via Suez principally to England and Scotland. They are known to have visited relations in Perth (Australia) who are presumed to have been members of the Leeves family. The Liner is also known to have called at Italy. Their tour later included a tour of France, and Germany.

Retirement years were dominated by bowls, friends, children, and grandchildren.

Alfred Joshua Burge died on lst February 1960, and Maud continued to reside at 918 w Heretaunga Street Hastings.

About 1966 Alice Maud married Jim Taylor who was an acquaintance from the Heretaunga Bowling club. Alice Maud pre-deceased Jim Taylor by about two-and-a-half years.

Tony Rule 2/3/96

Page 1

Edith Isabel Masters

(The second daughter of Alfred Masters & Alice Lydia Leeves)

Edith lsabel Masters was born on 24th June 1896 at the residential accommodation incorporated in the hop kiln building at 113 Selwood Road (renamed Windsor Avenue) Hastings. Given the attributes of her parents (Alfred Masters and Alice Lydia Leeves) there is every reason to believe that their home was adequately appointed, however, the Masters children found amusement in modestly declaring themselves to have been born in a hop kiln. The notion fitted well with the distinctive sense of humour that was so characteristic of Edith (and of her brothers and sisters)

School: Edith Masters is believed to have followed her older siblings and attended school initially at Hastings Central School in Karamu Road. On Monday 7th February 1910, at the age of 13 years and 7 months. Edith enroled [enrolled] at Hastings High School The school was then co-educational but was later to become the Hastings Boys High School. Edith attended High School for one year, and on Thursday 15th December 1910 at the age of 14½ years, she left school to take up “home duties”.

Employment: From the time that Edith left school, about 6½ years elapsed before she began her next known mode of employment. On 19th May 1917 she joined the *Bank of New South Wales in Hastings, at the corner of Heretaunga Street and Market Street. At the time of her joining the Bank of New South Wales she was aged twenty years and eleven months, and commenced with a salary of £75-0-0 per annum. Following two months as a probationary employee, she was elevated to Full Service status on 19th July 1917, and the event was marked with a pay increase to £100-0-0 per annum.

Edith was employed in a general clerical role. If her relatively regular pay increases were an indication or her performance, she is presumed lo have met or exceeded expectations as an employee. The pay structure and the very frequently stepped increases that applied during the era are interesting when compared to similar types of employment of many decades later. Her new or revised pay levels were applied from the following dates and for the amounts shown:

19/5/1917 – £75-0-0

19/7/1917 – £100-0-0

19/1/1918 – £105-0-0

19/7/1918 – £110-0-0

19/1/1919 – £115-0-0

19/7/1919 – £120-0-0

19/1/1920 – £125-0-0

1/4/1920 – £135-10-0

1/7/1920 – £145-0-0

1/1/1921 – £156-0-0

During the 4½ years from the date when she joined the bank’s employment on 19th May 1917 and until the date on which her resignation applied on 14th January 1922, ten different pay levels applied.

During her era, staff of her level were entitled to two weeks leave per annum for each full year of service. She availed of leave for two weeks from 22/10/15, and another two weeks leave from 7/2/1919, and two weeks from 8/12/20 (being the only full years of service)

On 14th January 1912, Edith resigned from the Bank of New South Wales to get married. The

Page 2

wedding occurred ten days later on 24th January 1922. Given that Edith and her new husband both lived and worked in Hastings, and were to remain in Hastings after the wedding, it might seem odd that she should resign to get married. However, the resignation was imposed by the banks’ rules of employment. The banks’ ruling arose from the fact that her husband was employed by another bank in Hastings. He worked for the Union Bank of Australia. The banks were then uncomfortable about the elevated risk of a husband and wife committing a breach of confidentiality on matters pertaining to their respective employer banks. In the case of Edith and her husband, the husband’s employment was granted precedence by the couple, and Edith elected to resign her employment from the Bank of New South Wales.

[* The Bank of New South Wales subsequently merged with the Commercial Bank of Australia to become Westpac Banking Corp, and later merging with Trustbank to become Westpac Trust].

Edith’s future Husband (William Orton Cowan): Orton Cowan was born 27th March 1896, and grew up in Lyttelton, Christchurch. He joined the Union Bank of Australia at its Lyttelton branch on Monday 21st October 1912, Orton was then 16½ years of age, and commenced as a probationary employee on a salary of £40-0-0 per annum.

On Tuesday 5th January 1915, immediately after the statutory New Year holidays, Orton commenced duties at the bank’s Wellington office as a clerk earning £80-0-0 per annum. His time there was relatively brief as he was transferred to the bank’s Gisborne office as a clerk on 11th October 1915. The First World War had begun about a year earlier, and Orton was required to undertake compulsory military training [Military No 30471 GNR. W.O. Cowan]. He attended a compulsory military camp from 6th April 1916 to 15th April 1916.

On Sunday 19th August 1916, while still officially attached to the Gisborne branch of the Union Bank of Australia, he was enlisted for full-time military service. He remained in the Army until well after Armistice Day (11th November 1918), and it was not until Wednesday 21st May 1919 that he was discharged from the army. On the day of his discharge he began one month of leave. This leave was without pay from either the army or the bank. On Monday 23rd June 1919 he commenced clerical duties again with the Union Bank of Australia but at its Hastings office, and now on a salary of £145-0-0.

Marriage: His transfer to Hastings was a significant event. It was while in Hastings that he was to meet his future wife Edith Isabel Masters. At that time she was employed at the Bank of New South Wales in Hastings. Approximately 2½ years later on Tuesday 24th January 1922 Edith Isobel Masters married William Orton Cowan. She was age 25 years and seven months at the date of her marriage. (Refer to National Archives reference No 1688 for marriage details)

They were to have only a further four months in Hastings. His employment was now a dominant element in their lives. He accepted a transfer to Christchurch and commenced duties there as a clerk on 2nd June 1922 on a salary of £260-0-0 per annum.

In 1931 they were known to be living in Rolleston Avenue in central Christchurch (on the eastern side of Hagley Park, and opposite the Botanical Gardens) On 29th September 1938 Orton had been promoted to the role of Sub-Accountant at the Cashel Street branch of the

Page 3

Union Bank of Australia. The following day the branch manager wrote of him as follows. “Good ability. Quick. Accurate. Neat. Duties very well performed.’

He was again promoted on 27 November 1939, this time he assumed the role or Branch Accountant at Cashel Street, Christchurch, and now with the more useful salary of £425-0-0 pa. A Branch Accountant was responsible for daily, weekly, monthly, and annual reconciliation processes, plus the supervision of subordinate staff, and the direct supervision of all other operational aspects of the branch’s activities.

Correspondence from Edith shows than in August 1939 they were resident at Flat 2, Salisbury Street, Christchurch. That address is again used on correspondence in December 1941. Their flat was in the top storey of a two story building which backed onto a manse.

Edith shared her brother Lester’s affinity for recreational pursuits in the high country. Edith enjoyed tramping in the Southern Alps and is understood to have engaged in such activities in the Arthur’s Pass area. Public transport from Christchurch to Arthur’s Pass was made easy by the regular rail passenger service between Christchurch and Greymouth.

Whether Edith herself was continuously employed during these years is unclear.

As at 30th September 1941, while still the Branch Accountant at the Cashel Street branch of the Union Bank of Australia, his annual report noted “Good appearance, personality, address [speech]. Conscientious, intelligent, efficient & reliable. Has good general knowledge and good control of staff. Keen in bank’s interests. Warrants promotion to higher rank. [Suggested] Small Branch Management’.

On 16th January 1942, Orton was appointed to the role of Audit Officer on a salary of £470-0-0 pa.

The role of Auditor involved travel throughout the country, and on some occasions Edith would accompany Orton while his Auditing assignments took him away from Christchurch (particularly those that involved audit work at the Hastings office of the Union Bank of Australia. These would give Edith an opportunity to spend a few weeks with her brothers and sisters.)

In 1949 Orton Cowan was transferred to the position of Manager at the Bank’s Feilding Branch. There they lived in the Bank-owned residence which was within a 10-15 minute walking distance to the centre of town. They were also provided with a Bank Car. (An Austin Devon of about 1951 vintage.)