- Home

- Collections

- THOMSON MJ

- Family History

- Dearer By the Dozen

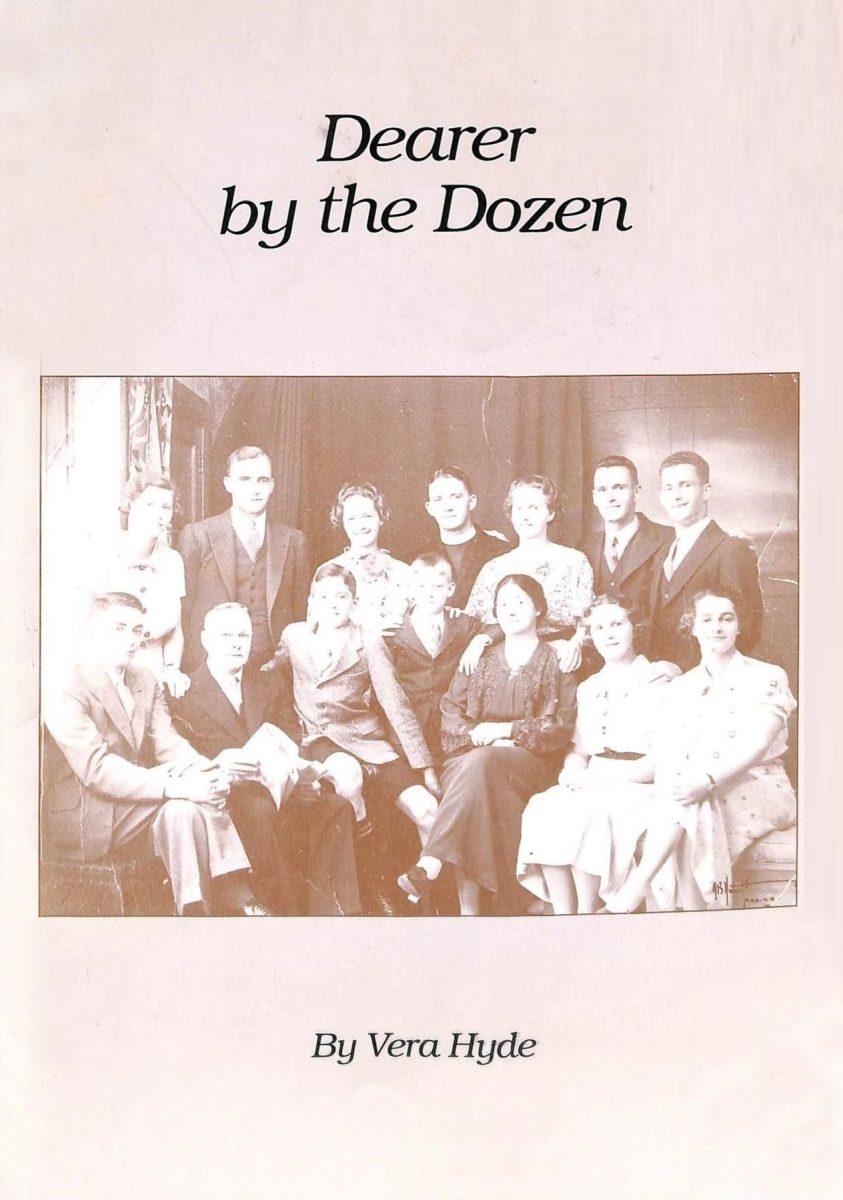

Dearer By the Dozen

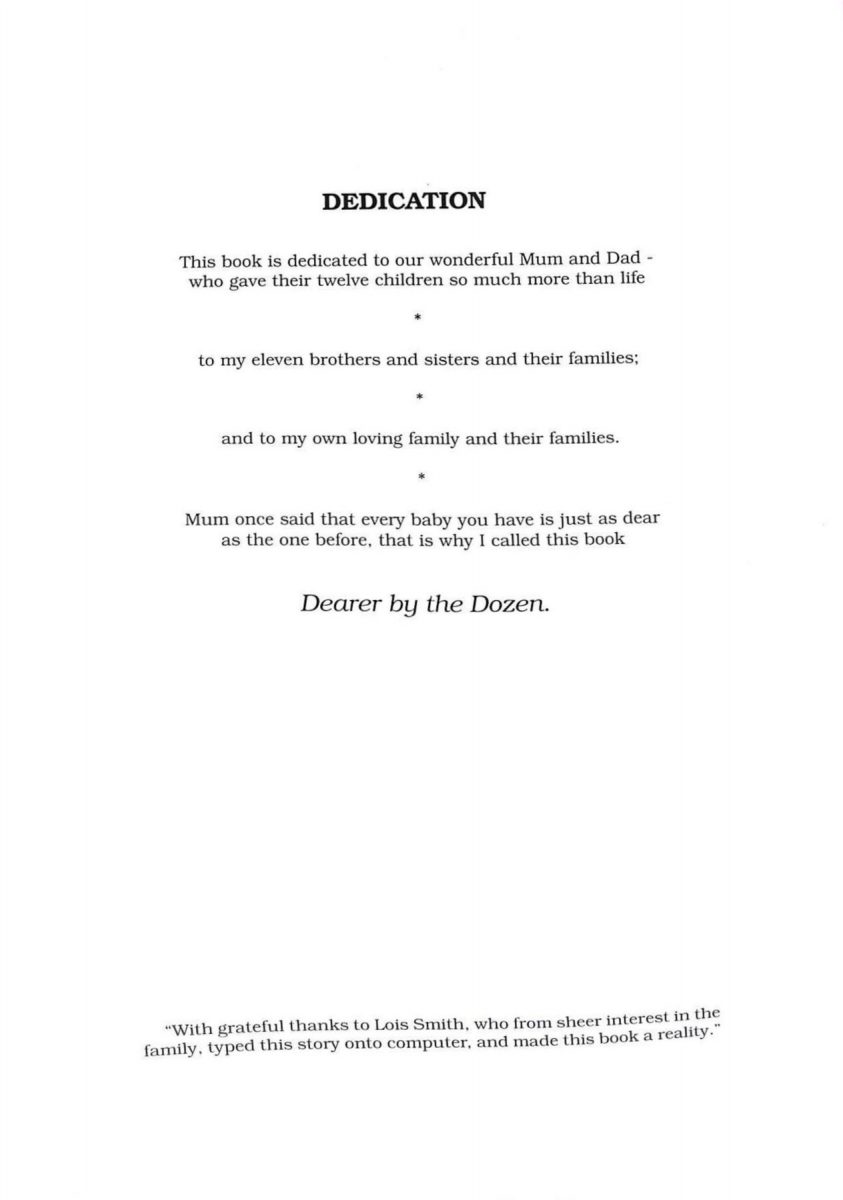

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to our wonderful Mum and Dad – who gave their twelve children so much more than life

to my eleven brothers and sisters and their families;

and to my own loving family and their families.

Mum once said that every baby you have is just as dear as the one before, that is why I called this book

Dearer by the Dozen.

“With grateful thanks to Lois Smith, who from sheer interest in the family, typed this story onto computer and made this book a reality.”

Page 2

OUR PARENTS & HOME

“Fancy being one of twelve kids! What’s it like?” one of the girls I worked with asked me this nearly fifty years ago and I told her of the fun it was, making her quite envious. Many years later at a Mothers’ Union meeting in Cambridge when our speaker couldn’t come, one of the members asked if I would tell them a little about our family life, and what it was like belonging to a family of twelve – seven boys and five girls. I found such pleasure in chatting away about the family that after sixteen years and eighty-one “talks” later, and because of the great interest shown by so many people, I decided to write this book.

Our Mother, affectionately “Mum“ to us all, was born at her parent’s home in Waghorne Street, Port Ahuriri, Napier in 1883 and was christened Susan Rebecca Rolls. Her Father Mark Rolls, was a baker who made only a few hundred loaves of bread a day which he delivered only on the flat, refusing point blank to deliver on the hill. He was a very heavy gambler and lost a great deal of money at the races, and was also an avid buyer of unnecessary and sometimes useless articles at auction sales. Once he even bought a chair with only three legs. He was apparently a hard man too. One day he came home and found Granny was out (she was only at the store across the road) and he was terribly annoyed about it. Granny was so upset she declared she wouldn’t go outside the gate again, and she didn’t for almost twenty years, until Grandad died. She was a short cuddly person and we all loved her coming to our place, which she did from when I was quite young. She wouldn‘t let us do the dishes when she was there and how we loved her coming!

One vivid memory is of Granny sitting in the rocking chair singing away to us, and in particular the song, “The Boers have got my Daddy”. She didn’t have any teeth for many years as she got older, but could chew a steak as well as anyone with a good set of teeth. She didn’t wear glasses either, she just said God didn’t intend us to have any of those false things. She died aged 92 still without glasses and teeth.

Mum attended the Port School until she reached standard six then at thirteen went to work as a tailoress for the Misses Laurie and Miller, receiving no pay at all for the first year, five shillings (50 cents) per week for the second year, seven and sixpence for the third and so on, and by the time she married at age twenty she still earned only one pound ($2) per week. The only work for women and girls in those days seemed to be dressmaking, millinery, or domestic work.

Dad was also born at Port Ahuriri – in 1880 – and his father was John Prebble of J, & W. Prebble. Their business was later sold to Messrs. Barry Brothers. When Dad was three months old his parents moved to a house (a little more than a shed) in Goldsmith Road, or rather Goldsmith Terrace, and the only washing facility at the new home was a copper and kerosene tins in the back yard. Grandma came out from England to marry Grandad and was quite horrified at the way she had to live. As their family increased, (they had nine children), two bedrooms and a bathroom were added to their home at a cost of forty seven pounds. Unfortunately the receipt for the payment was mislaid and when another account came it had to be paid again.

Dad started work as a joiner at Bull Brothers at the Port, earning 5/- a week for the first year, 10/- the second, 13/6 the third, and 15/- per week for the fifth year. When he married at twenty-three he was earning two pounds nine shillings and sixpence (not quite five dollars] for a forty eight hour week, and later as

Page 3

Foreman the highest wage he got was under six dollars. He held the position of foreman for twenty three years until a heart attack forced him to give up work. He had worked at the same bench for forty years.

Mum and Dad started going for walks after Sunday School when Mum was fifteen and a half and in 1904 when she was twenty they were married at St Andrew’s Anglican Church in Ossian Street at the Port. Mum was married in a navy blue costume and I don’t think they even had a wedding breakfast because of lack of finance.

Our house was built in 1905 – just the complete shell and roof by a builder – and Dad finished the whole of the rest of the house at night and at week ends, or I should say on Saturdays, because he wouldn’t do any building work on a Sunday, and it took him quite a while. Only one room, plus the kitchen and bathroom was really finished when Mum and Dad and three month old Jack moved from their house in Hardinge Road. When number two, three, and four were born they were brought up to the sound of plenty of hammering, planing and sawing of timber.

Mum and Dad’s bedroom was a good size – 12 x 12 I should think, and the second bedroom was large enough to sleep five children because in later years we had two three quarter beds and a single one in that room.

As the family increased another bedroom was finished, and then the only place to extend was the basement, and I’m sure neither Mum nor Dad ever dreamed they’d have to extend their home to accommodate fourteen people.

As the house was built on a sloping section, a wall 10 feet high was put up so many yards from the house and work began on excavating the clay from underneath the house to fill in the ground in front to make a lawn and garden. The wall went right across the front of the section. The work was done at night and at week ends, and Dad and the two eldest boys – Jack and Reg – were busy with picks and shovels slogging away for months. For the room under the house, beams were put in to replace the studs and finally a room 20 x 14 feet was ready. The two eldest moved into this bedroom and as another baby arrived, the next eldest boy moved down, until in the end there were five boys sleeping there. Outside this room which was set back five feet under the main structure. Dad installed a horizontal bar which was used daily by the boys over many years. Luckily there were no falls from it which was just as well because the only thing to fall on was concrete! The bar is still there in 1990.

There was no access between this room and the main house so wet or fine it was a case of out in the open and round the house to the side door of the house. The bedroom underneath was always referred to as “Down below” and when you were down below the inside of the house was referred to as “Up Top.” Later Dad and the older boys made part of the front verandah into a lovely big porch and this held three extra beds so we were well off for accommodation.

Dad was very strict and hard and a stern disciplinarian, but played with us a great deal. He also taught us many things we’d never have learned had we been left to our own resources or if the training had been left to Mum, who said she was just too busy and didn’t have time to teach us, finding it much quicker to do things herself. This of course was only when there were so many young ones. When we were older she taught us a great many things.

Dad taught the older members of the family when they were five years how to wash socks and handkerchiefs and how to scrub the bench and side

Page 4

back steps. I can remember so well being stood on a chair with a sack apron tied round my chest and being given the sand-soap and scrubbing brush and shown how to scrub the bench and steps. I think we all loved our jobs too.

Dad also nursed us all to sleep when we were toddlers – quite often two at a time – and he said for as long as he sang songs we stayed awake, but as soon as he sang hymns we went to sleep. He and Mum would carry the sleeping toddlers off to bed and they didn’t stir when put down. It was a different story during the war when I lived at home, Dad nursed our little daughter to sleep but as soon as he put her into bed she wakened and I remember him saying quite sadly “Not one of my twelve ever did that.”

He was always busy in the garden at weekends, but never missed Church on Sunday evenings (that was his only outing) and after Church he always went cross the road to visit Grandma Prebble. In the evenings during the week he was either sitting astride a form in the kitchen mending shoes, or down under the house in the workroom making some article of furniture, or perhaps a toy or cart for the boys. When mending shoes he put the shoe last on the ironing blanket on the form to deaden the sound of the hammering, and he didn’t at any time hammer after nine o’clock at night as he didn‘t want to disturb the neighbours. That applied when he was building the house too. Apart from the big brass bedstead in the main bedroom and a three quarter iron bedstead in the front bedroom, he made every bed and piece of furniture in the house The drawers in the dressing tables and chests of drawers ran in and out as if on satin, and even the very large drawers in the main chest pulled in and out with ease. His work was perfect, and Fred inherited this perfection of work. When Fred was eighteen months old Dad gave him a little hammer and he used to hammer away on pieces of wood, and by the time he was three he could hammer in tacks very well, and during the weeks, months and years that followed, the fender in front of the fireplace in the kitchen and the wooden end and legs of the settee were simply filled with tacks. I remember so well that little wee boy hammering away day after day. Working with wood was surely in his blood. It was no trouble to Dad to make a new fender, and legs and end for the settee.

Dad was just over sixty when he became ill with a heart attack and he had many visits to hospital during the next three years. One of the sisters told us that in all her years in the hospital she’d never before known a man so proud of his family. He did love seeing us when we went to visit him and seemed to take great pride in introducing the different members of the family to the nurses. He died when only sixty-three, and I’m sure he often sees us now and is very proud still of his twelve children. At least I hope he is.

Reg was the first one to have a car and he was so very good with it, often taking Mum and Dad for drives at the week end. I often think now with all the family having nice cars, how Dad would have loved the different outings he could have had. The doctor thinks Dad strained his heart with all the heavy work he did after the earthquake, and after never having had an illness he found it very frustrating just pottering about. He had a very full life up to the time he first took ill and we thank God for his example and help to us all.

I’d like now to write more about our Mum who was the most placid soul one could meet. She really was quite exceptional, a wonderful Christian, a very loving and concerned mother, a very great worrier, and oh so funny with her superstitions.

Page 5

One day Bert our parson brother, said to her, “You can’t be superstitious and be a Christian too Mum,” and she replied, “I can,” and she was that way until she died. When Fred went overseas during the war she gave him a piece of ribbon – his lucky colour – to keep in his pocket all through the war which he did to please her. She was so sure it helped him come back. When we were young our finger and toe nails were never cut after our bath on Saturday, but always and only on Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday. Monday was for health, Tuesday for wealth, Wednesday the best day of all, Thursday was for losses, Friday for crosses, and Saturday no luck at all. We were always encouraged to go outside and look at the new moon, never through a window. If we forgot anything and went back for it we had to sit down and count ten. Even when Mais and I were going to work, we’d be dashing off to catch the bus when suddenly one of us would remember something forgotten, tear back into the house, sit down and count seven in a breathless rush, grab the thing forgotten and off we’d go again.

When in later years Mum went to the chiropodist she would go only on the first three days of the week. If ever we were starting something new like making a frock or such like, we were always encouraged to start on the first three days of the week and when the moon was waxing. It didn‘t matter which day we finished the article it was the beginning which was so important

Visitors were asked to leave by the same door as they entered, otherwise, according to Mum, they brought sickness to someone in the family, and this she firmly believed. One day Dr Gilray called to see someone who was ill, and after his visit was standing beside the front door talking to Mum. When he came to leave Mum gently took him by the arm and led him to the side door saying. “You don’t mind going out the way you came in do you Doctor? If you go out the wrong door someone in my family will be ill.” It didn’t seem to occur to her that someone was already ill and that‘s why the doctor had called!

As we got older everyone teased her unmercifully about her superstitions but she took it all in good fun and just went on being superstitious.

I was at a Missionary meeting one day and on the way out dropped my glove. The man behind me picked it up and I looked grateful but said I wouldn’t say anything as it was bad luck to thank anyone for picking up a glove. He just looked at me in amazement, put his hand on my head and said to all assembled, “Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve just been discussing the heathen and we have one in our midst.” Everyone laughed, but I never forgot that experience and although I was only eighteen at the time. I’ve never been superstitious since.

Mum had all sorts of wise sayings which she passed on to us, like a ‘stitch in time saves nine’. ‘There’s no disgrace in a darn, but there is in a hole.’ ‘Least said, soonest mended,’ etc. She couldn’t bear to hear people ‘going on’ about anything and if it was about anyone she’d say

‘The poor thing can’t help it’ or “You can’t have been meant to do that, or go there.” We were constantly told to turn the other cheek and not to worry too much about what others said. ‘Five minutes with your feet up are worth twenty with them down,’ and this she took note of all her life. She was never too busy to have twenty minutes or half an hour’s rest after lunch every day, and I‘m sure this helped towards her wonderful good health. She still had her forty winks as she called it even with all the family about her.

Page 6

Another wise saying she used to have was, ‘There‘s nothing, neither good nor bad, but thinking makes it so.’ Two of her favourite sayings were ‘Worry is like a rocking chair; it gives you something to do but doesn’t get you anywhere’, and the other was given to her by brother Bert and that was – ‘Everything that happens can be so taken, that the net result will be far better than it would have been if it hadn’t happened.’ This gem was pinned up in the kitchen for all to see.

How kind she was that Mum of ours. My last term in standard six I came last in the class of fourteen and went home weeping with shame, but she just put her arm round my shoulders and said, “Never mind dear, you can’t be good at school work and a great help at home too. What a diplomat. I loved staying home if ever she was ‘snowed under’ and consequently missed quite a lot of schooling. Anyway my powers of concentration were practically nil.

As the boys grew up they had several names for Mum. She was called Mom, Momma, Susan, Susie, and occasionally Mother, but mostly Mum. Poor soul, she came in for more than her fair share of teasing from those seven boys, but she took it all in good fun and in her usual placid way.

She was an avid reader of the NZ Woman’s Weekly from its inception and would very frequently quote little bits of information, so much so that if ever she started a sentence with, “I read,’ everyone would volunteer ‘In the Woman’s Weekly!’ One day she read quite a long article about the healing qualities of onions. She had had piles for many years so after reading about the onions what did she do? She cut some up, placed them in a chamber and then in the privacy of her bedroom sat for several minutes each day, declaring later that her piles were much much better. The ragging after that lot was tremendous but she laughed it all away.

When she was seventy Mum said. “Now I’ve reached my three score years and ten I don’t mind when I die, and I don’t want any of you to grieve for me.” She lived another ten years and died in 1963 shortly after her eightieth birthday. We tried not to grieve but her passing left a great blank in our family life. On the evening of the day of her funeral seventeen of us went out to her grave to see the flowers and while we were there, brother-in-law Mick suggested we sing Mum’s favourite hymn – “The Day Thou gavest Lord is ended.’ but although we all started with great voice, none of us could finish even the first verse. I’m afraid it was too much.

Mum had died quite peacefully after a fairly short illness, leaving behind twelve devoted members of her family, plus sons-in-law and daughters-in-law and daughters-in-law and grandchildren equally devoted. I’m glad she lived to see how well her family had fared. If ever anyone deserved a medal for everything connected with family life, she did.

Page 7

EARLY DAYS

After the experience of having baby No. 1, which by the way she had at home with only Dad to help her, Mum said she didn’t really want any more but the other eleven were all welcome when they came. At one stage there were four under three and a half, and later eight under ten, and when Mum was thirty two she had nine children under thirteen and Dad was earning three pounds, seventeen and Sixpence (about $7.75) a week. With no Social Security what a mammoth task it must have been feeding and clothing all those children on such a meagre wage, By the time there were twelve it wasn‘t at all bad because some of the older ones were working and contributing to the family income. The most difficult time must surely have been when there were nine children under thirteen.

The first eight babies were born at home, and the other four at McHardy Home in George Street. Incidentally the only holiday Mum had in those days was going into the home to have a baby. She said she loved that rest.

Dad was foreman of Bull Brothers when the big house was built for Mr and Mrs McHardy in George Street, and in later years when it was given as a Maternity Home, Fred was one of the first babies born there.

It is hard to believe that Mum managed without a pram for the first seven babies, but if there had been one there wouldn’t have been any outings with so many little ones to cope with. She was quite content to stay at home as her husband and family were her life and she was passionately fond of babies. When she was young she used to dream of the time when she would be married and have a baby to nurse while she was having a meal. I wonder how many times she did have a baby on her knee at meal times.

There always seemed to be a baby in bed with Mum and Dad and I well remember the swinging cot near the bedroom wall in their bedroom, and the cradle beside the bed. At night Mum tied a string to the swinging cot and on to the wire wove of their bed and if the little one in the cot cried she would pull the string and rock it; if the one in the cradle cried she would rock it, and if the one in bed cried she fed it! What a remarkable person she was. She surely was born to be mother of a large family and was able to cope with surprisingly little sleep.

We all, except Tom, had dummies when we were babies and toddlers, and Tom was the first one of the family to have his tonsils and adenoids removed which rather quashed the idea held at that time that dummies caused adenoids. Mum believed that dummies if kept clean, were worth their weight in gold. My fervent belief too.

On Saturday morning when we were young we weren’t allowed out of our bedroom until 7am after which we went in on to Mum and Dad’s bed – Six or seven of us and were given our sweet ration for the week, and that was a halfpenny Sante bar of chocolate. How we loved those moments which unfortunately weren’t very long because Dad had to go to work at 8 am.

After breakfast there were many jobs to do and these were listed by Dad on Friday nights and the list was hung behind the washhouse door. He divided the jobs out between us and we had different chores each week, but didn’t know until Saturday morning what our particular job would be. There were steps to scrub, plus the kitchen bench and these jobs were kept for the young ones. Then the kitchen scullery, pantry bathroom lavatory and washhouse floors all had to be done. One would scrub and the other wipe up following the scrubber

Page 8

with a bucket of clean water and cloth. When scrubbing the bench and steps we had to use sandsoap and would scrub away until there was a nice lather, then draw pictures or print and generally play round with the soapy film until the steps or bench came out as white as snow!

Window cleaning was another of our jobs of work, and we cleaned them with a wet cloth rubbed on white stuff called ‘Bon Ami’. This left the windows covered in a white film and on these too we would draw and print. With one of us either side of the window, both sides were done at once, and when cleaning off the film it was easy to see if smudges were left, consequently the windows positively gleamed. They were the old fashioned pull up and down type and we were able to reach most of the outsides from the verandah. When the sun porch was built outside panes were left to Dad and the boys to do from a ladder.

Knives had to be cleaned with a cork dipped in water and then in some brown powder, rubbed until all the powder disappeared, then polished with a dry cloth.

Soot had to be cleaned from the coal range and the range cleaned and polished with black lead. It used to look so beautiful when finished and whoever was doing it would feel very proud of their efforts.

Bedrooms were tidied, cleaned and dusted and as we didn’t have a mop we had to go on our hands and knees with a duster on which was a dab of kerosene to collect the fluff and dust. The floor and skirtings were done properly too, beds were shifted out and dust removed from behind the bedposts, because Dad inspected our work when he came home from work at lunch time. If it wasn’t done properly we were sent back to do it again, consequently at a very early age we learned, ‘Lazy bones takes the most pains.’

For many years the floors were just stained in passages, lounge (or dining room as we called it) hall and bedrooms, then later Mum and Dad bought a narrow strip of carpet for the passage and hall. Not having a carpet sweeper we cleaned this by sprinkling damp tealeaves then sweeping backwards and forwards with a stiff broom until the tealeaves were coated with dust and swept on to the woodwork at the side of the carpet. These had to be swept up and the woodwork cleaned and polished. What a miraculous article the carpet sweeper seemed when we first had one, to say nothing of the vacuum cleaner in later years when we had more carpet.

Lamps had to be cleaned and trimmed in the early days, and wax removed from candlesticks which were then cleaned and washed. Another job was cutting up newspaper for the “lavatory” as we called it. There was no such thing as toilet paper in our young days, or if there was it wasn’t in our home. Hundreds of squares of newspaper were cut up each week and for these Mum had made a holder out of sugar bag trimmed with fancy braid or binding, and Dad nailed it to the wall in the lavatory, or toilet.

Slops had to be emptied every day of the week and we had turns doing this chore. Armed with a bucket, a jug of clean water and a cloth, we had to empty the chambers, rinse them out well then dry them. As we were not allowed to leave the bedroom once we’d gone to bed, chambers were kept in every room.

Gardening was a job most of us disliked but which we did uncomplainingly. We wouldn’t dare complain. When Dad said he wanted so and so to weed between the tomatoes, beans or somewhere else, we didn’t dream of objecting but got on with the job.

Page 9

When eventually the back yard was concreted, and the side path too, the yard had to be swept. It all looked so nice after it was done I don’t think we minded doing it.

When I was about eleven, Mais fourteen, and Bert twelve, we used to get up at 4.30am on Monday mornings to do the washing which had been put into soak the night before – two tubs full.

Bert always got up first and lit the fire, then called Mais and me. I fed the clothes into the wringer while Mais turned the handle. The sheets were then put into the copper, boiled for five minutes then Bert with the copper stick would lift the clothes out onto a board. The washing was then lifted over to a tub, rinsed in clean water, wrung again, put into a tub of water made blue (for whitening clothes) with a blue bag. After this final rinse they were wrung out again before being hung out to dry

On fine days they were hung out on a long line down in front of the house, and on several lines on the side lawn. On wet days they were hung on lines on the verandah which were zig-zagged all along the side and front verandahs. The washing was never cancelled as there was always the verandah.

My job was to rub all the soaked handkerchiefs, (the soiled ones were boiled in a large old pot on the gas stove in the scullery.) Towels, socks and nappies were next, but of course socks didn‘t go in the copper. We had a busy time but Bert used to make us laugh so much we didn’t notice the time. Mum frequently came out to remind us of our neighbours!

When jobs were all finished we were allowed to play for the rest of the day. Playing shops was a favourite pastime and Mum would give us oatmeal and sugar mixed together in an enamel bowl, and this we’d sell by the spoonful. It was lovely to eat. On occasions we were allowed to buy liquorice straps from the store at the top of the hill, and these we’d tear down in thin strips and from our shop we’d buy a strip at a time. We also sold broken biscuits which could be bought in the real shop for a penny a bag. Biscuits in those days were not packaged in packets but came loose in large tins, and by the time the shopkeeper had handled a tin of loose biscuits many times during the day he finished up with many broken ones.

We had imaginary homes in different parts of the yard or lawn, and our imaginary dolls, husbands and wives were very real to us and we played quite happily for the day. Our dolls at that time were pieces of wood wrapped in a duster or piece of fancy cloth and were our only toys, but we were so happy.

If we ventured inside Mum always found a job for us to do, so we kept well out of the way.

Turns doing the dishes from quite an early age was a good idea, and while Dad washed up, two or three would help him. Dishes in the early days weren’t so bad because we each had our dinner on an enamel plate, then we were given half a slice of bread with which to clean our plates ready for the pudding. It was difficult to tell whether or not the plates had been washed when we had finished rubbing them with the bread, they shone so beautifully! We ate the bread we cleaned our plates with so it wasn’t wasted.

I remember someone once speaking to Dad about their children arguing while doing the dishes, and he told them to get the children singing, because as he said, “They can’t argue while they’re singing.”

Page 10

I have such lovely memories of all the singing and how wonderful the harmony was when we were older. Dad and Bert sang tenor and the other boys bass. Even if it wasn’t our turn for the dishes we would stay about to join in the singing.

There was no shouting or noisy argument in our home, and no talking at the meal table unless we were spoken to. Dad had a six foot piece of dowelling which lay along the table and if anyone had their hands too far on the table. or elbows up, or talked out of turn, ‘The Stick’ was used to advantage. We had very chatty meals but only spoke when asked questions, or we had something to tell Mum and Dad. Punctuality at meals was a must, and grace was not said until everyone was seated. It applied to every meal all through our lives at home, and there were no stragglers coming in to any meal, breakfast included. We were all there ‘on the dot’.

We all, boys and girls, had to take turns getting the breakfast from when we were eleven years old. The boys gave up when they were twenty-one, but the girls went on forever. I remember longing to be eleven as I thought one must be very grown up at that age to be able to get breakfast for such a number, of course when I was eleven there were only nine children.

Every night after tea Dad played games with us. In the summer time out on what was called ‘the Green’ outside our property in Goldsmith Terrace, and on the verandah if it was wet. In winter we played indoors. Outside we played Bar the Gate, Leap Frog, Hide and Seek, French Cricket, cricket. etc. and inside Leap Frog, Hide and Seek, Hunt the Thimble, etc. What a noise there must have been on winter evenings on those bare boards in the passage and hall. I asked Mum in later years how she put up with all the noise and she said, ‘Happy noise never bothered me: arguing or grizzling I couldn’t tolerate.’

Most times we made our own fun, and while I’m sure there must have been arguments we took good care Mum and Dad weren’t about to hear.

Some cold wet Saturdays in the winter time, Mum showed the girls how to make ordinary clothes-pegs into dolls, by putting faces on them and dressing them up in pretty material, tying the material on with a spare piece of ribbon. Dad helped the boys make carts, and these were always used when we were going to the beach for a picnic.

Saturday night was bath night and the water had to be heated in the copper and carried across the yard in buckets to the bathroom window and handed in to someone old enough to take it. Dad or the boys would keep the copper fire going until all had bathed.

We of course used the same water for two or three baths, and were always in two at a time. On rare occasions Mum would have to boil a couple of sheets on a Saturday, then the water was used for the bath and we used to love having a bath in the lovely soapy water. I couldn’t think of anything worse now, but we loved it particularly when the water was being emptied out and we could slide up and down the bath.

We had three large galvanised iron baths hanging on the fence in the back yard, and on very cold nights Dad brought one of these into the kitchen, put it in front of the range, carried in two or three buckets of water from the copper, and there we’d have a lovely hot bath in a beautifully warm room. The kettle was always boiling on the stove and that water was used to top up the bath water when needed. The front of the range was left open so we could

Page 11

see the fire in the grate and feel the heat. At a time when there were eight young ones to bath it must have been a real contract for Mum and Dad. How wonderful it was for them when eventually electricity was installed and we had plenty of hot water, and how magic we thought the electric lights, instead of gas light, lamps and candles.

On Sunday afternoon after Sunday School, and when later Mum had a pram, we were taken for a walk down to and over the embankment and home over the Westshore Bridge. Mum quite often wheeled the two little ones in the pram, Dad had one on his shoulders, and we others walked along with them. It was a long walk for children but I‘m sure it was good for us as we were a very healthy bunch

Sunday nights after tea we sang hymns from the old Sanky hymn book and when old enough to go to church at night, Dad and six of us were in the choir. We loved cold wet Sunday nights when we were young, because Dad would light a fire in the big front bedroom fireplace and there we would have our tea of toast and butter or toast and jam, all sitting on the floor round a lovely fire. After tea until Dad went to Church we would have a concert when those of us who could would give an item, after which the Sanky hymn books were brought out and we’d have our hymns. Bed time was always at 7pm, until we were twelve years old for we older ones, when we were young. As the younger ones came along times were changing and Dad was more lenient.

Mais and I loved going to bed on the nights we’d had a fire and tea in the bedroom. The glow of the dying embers gave a wonderful feeling of security and warmth and we felt so very comfortable. Life for us was very uncomplicated.

I don’t remember how old I was when I first heard a radio, but I remember it so well.

Neighbours down the road bought one and they used to open their front room window and let the sound of the music echo round the hill. It was beautiful. The first piece of music we heard coming over the air was ‘In a Monastery Garden’ and I shall remember it always as I heard it that night. We were all out on the back verandah on that lovely moonlight night listening to the magic sound.

Something that created a different sound was a strap! One day Reg was coming home from school and he found a long black leather strap on the sandy road near the gasometer and near where the Port School now stands. He brought it home and no doubt was sorry ever afterwards because he was the first one to get a hiding with it. That strap hung behind the kitchen door for many many years and was used quite a bit. I think our parents thought ‘action speak louder than words.’ It didn’t seem to do us any harm though.

There was lots of mischief afoot at times, and getting into mischief without Mum and Dad finding out was quite a feat. Sometimes when parents are very strict at home their children aren’t so well behaved at school, and I often wonder if we were a little bit that way. I remember being strapped an awful lot in Standard six and at the end of the year when I was leaving school I asked the teacher why he strapped me so much, and he said, ‘You took it better than the others’. Some excuse. I know I was always blamed for talking whether I was or not, and the strap was always used

Reg and Jack I know once or twice took fruit from the neighbour’s garden, and also played knick knock on people’s doors, but I don’t dare think what would have happened if Dad had found out.

Page 12

Sometimes, when it was wet when we came home from school we took off our shoes and socks at the bottom of the hill and walked home in the gutter to enjoy the water flowing down, and then put our socks and shoes on again before entering the house, because on wet days Mum inspected our shoes when we got home to see whether the sides of our shoes showed we had walked in puddles!

School in those days was just lessons all the time with one period of sport per week, and once a year lots of practice for the Grand March in readiness for our wonderful School Ball. School wasn’t school without ‘tables’ and the twelve times tables were ‘sung’ every day, consequently it was very easy to remember them. I remember Mum saying how they used to sing some of the spelling words and always remember how to spell across with just the one c A C R O S S I unconsciously sing it to myself whenever I have to write or type it.

The strap or cane was used a great deal in those days, sometimes unfairly, but I doubt if it did much harm. At least the teachers had discipline in the classes and everyone was able to hear what was being said by the teacher and they were able to get on with their work.

What little horrors children are at times. When our basketball or football teams were playing one of the other schools, the children would go round chanting – ‘Port’s a sport’, ‘Napier Central have all gone mental’, ‘Napier South needs a kick in the mouth’, ‘Nelson Park are afraid of the dark,’ or something like that. At the time we thought their chanting quite humorous, but it wasn’t very nice to have such rivalry, although I expect it exists today.

On occasions someone at school would report that a diver was going down in the Iron Pot (where the fishing boats were tied up) at about 4pm, so we’d tear home after school and ask if we could go down and see the diver and it was fascinating to watch him preparing for his dive. Donning the very heavy suit the huge great boots which made it almost impossible for him to stomp to the side of the boat, and lastly the massive headpiece which had to be screwed, and with all the air pipes and chains attached to him he looked like someone out of this world. The men on the boat held the chains while the others assisted the diver over the side. Coming up out of the water later he looked like a huge monster breaking the surface of the water.

Another great interest for us was to watch Mr Riddell busy in his blacksmith shed shoeing the horses. We were fascinated with the fire and the anvil, and the sound of the big hammer on the red hot shoes, shaping and turning them. Whenever we had to go on a message to the Port we used to ask Mum if we could watch Mr Riddell for a little while. The bottom half of the shed door was closed, and the top half open, and we would lean on the closed half quite carried away with what we saw. I used to wonder how on earth Mr Riddell could get clean each day!- his hands used to get so dirty, and so did his face.

At one period in our school lives, Dad had an ulcerated leg and was home from work for six weeks. We children were home part of the time because of a polio epidemic, and Dad used to set our school lessons for us there on the verandah, and we’d sit at the long desk doing our work. Dad or Mum would ring the bell for playtime in which time we’d climb the walnut tree, skip, play ball and generally have fun. After a quarter of an hour, the bell would ring again and it was back to school work until lunch time. It must have been easier organising several of us than it would have been giving lessons to one child, because when they’re shared, lessons are much more enjoyable.

Page 13

Every member of the family attended the Port School and there was a Prebble at the school in an unbroken line for fifty-three years, Dad’s family all attending there. Bert and Peg seemed to be the brainy members of the family as they were both Dux of the school in their respective years.

When Mais was eighteen she took five of us out in the train to the Hawke‘s Bay Spring Show. I was fifteen and a half at the time and the other four younger. She looked very pretty in a new dress and hat, and felt very elegant until a man called out from one of the sideshows and said to her, “Come on Missus and bring your kids in,” Poor Mais felt like a pricked balloon, to think that at eighteen someone thought she was the mother of five children the eldest one fifteen. I’ll never forget that day.

On holidays, after school on school days, if it wasn’t our turn for doing veges, etc, or when we’d finished our jobs, we played all sorts of games outside and in, and with friends from up the road we had a wonderful time. Sometimes we played up the hill sliding down on cabbage tree leaves, but we just had to hear the bell ring and we were home like a shot.

As can be imagined, money had to stretch a long way when we were young, and as the family increased another new bed was needed. Dad made the bed, and Mum made a mattress case and we children spent hours and hours cutting up old material with which to stuff it. We cut up old socks, worn out blankets and any worn out clothes, and many blisters on our fingers and thumbs were the result. The mattress wasn’t at all comfortable really, but I don’t think we noticed it too much. A friend told me that Mum said she had to stuff cushions with newspapers at one time, but I don’t remember that.

A very dear friend of the family worked in the Salisbury Tearooms in Hastings Street, and every Friday night at about 8.30 or 9pm two or three of us would walk all the way to town from Goldsmith Terrace and collect left over soup and other food. The soup was carried all that way in a large gallon billy, and many rests we had to have on the way. We weren’t very old at the time either. Sometimes there were scones and sandwiches too, but we could carry them only if there were three of us. I think I was about eleven when I first went with Mais and Bert, and I know I thought it wonderful having to stay up that late. This period was all very early in the nineteen twenties.

When we had our hair cut, Mum or Dad would slip a basin on our heads and cut our hair that way to make sure it was straight. When I see myself in school photographs now it just looks as if it was cut that way too!

It looked awful, but I can’t remember it concerning me at the time. Of course that way of cutting hair didn’t last long, thank goodness.

Mum had a passion for cleanliness and many a time she‘d lick her finger and rub behind our ears, on our necks, wrists or ankles, to see if “grannies” appeared, and if they did we were sent to rewash ourselves. Our heads were also inspected for lice or nits as I think they were called and I remember being very embarrassed going to school late one morning because Mum had found a couple of lice in my hair. The teacher had to have a note about it and I felt awful. A girl in our class who had long hair, wore a black velvet band round her head and we could see the little grey things crawling on this band. The lice mostly seemed to occur in long hair and when short hair came into fashion the position eased quite a bit. I think mothers were better able to cope with the hair washing more often when the hair was short.

Page 14

I don’t think any of us possessed rain coats, consequently when it rained we couldn’t go to school. If it rained when we were at school and we got wet coming home, we weren’t able to go next day if our shoes and clothes were still damp, as we had only one pair of school shoes. Later on when Mais and I were older, if it rained when the children were at school, whoever was home helping Mum at the time would take all the lunches down and so save them – the children – getting wet at lunch time.

Mum was very particular about anyone going out after a hot bath, as she said all the pores of the skin are opened and they let in the cold air. Another thing we weren’t allowed to do was go for a swim immediately after a meal, as we were told the blood rushes to the head when eating, and ‘If you dive in the water straight away you’ll sink to the bottom and not come up again!’ She was most careful with us all and I’m sure it contributed greatly to our good health. It needed endless patience to instruct so many children, but Mum had an abundance of that and she said she reaped her reward in later life.

Going to our Aunt and Uncles in the country for a holiday was supposed to be a highlight, but oh dear how homesick some of us used to be. I remember one time on a Sunday out at “Okawa” in Fernhill when I was eight, I was swinging on the fence and singing to my self very fervently, ‘PLEASE Mum and Dad come and get me’, when in the gate at the end of the paddock came Dad’s friend’s car and he had brought Mum and Dad out for a visit. I managed quietly to beg them to take me home, which they did, and oh how thankful I was. I think it was the pitch blackness of the country that worried me so much. Also the toilet was out the garden gate and down a track in the paddock near the house. One day I was held up there for over half an hour by a big billy goat.

Many tears and much calling and banging hailed one of my cousins who came to the rescue. There was no gaslight at all at my aunts, only lamps and candles, and I think this helped to make things seem so eerie, particularly when we were going to bed.

Home was such a wonderful place, and what happy serene times we had. We look back on our lives with very thankful hearts for such a happy childhood.

Page 16

ILLNESSES AND ACCIDENTS

Each member of the family seemed to have one serious happening apart from the usual childish ailments, but it was amazing how few accidents there were with such a large family.

Jack, the eldest, was helping Dad erect a fence by the back yard. The posts were in and Dad had cut the slots out to take the top rail which was sixteen feet long. They put it in place and Dad asked Jack to hold it in the middle while he went to get a chisel to fix the alignment. He told Jack not to knock it, but a boy like Jack gave it one bang with the hammer thinking that would fix it and down it come right on his foot, cutting through the leather of his sandal and into the base of his big toe. Mum very nearly fainted when she saw it and there was nothing she or Dad could do to stop the bleeding. Of course it needed stitching. Dad carried Jack on his back all the way up to the hospital and we used to wonder how on earth he did it, as Jack was about twelve or thirteen. The hospital was at the top of the hill so it was some feat carrying a boy of that age. Jack spent over a month in hospital mainly because of blood poisoning and the wound taking so long to heal. Incidentally he put on so much weight through just sitting about in hospital that when it came to getting dressed to come home, he couldn’t do his trousers up, he was so plump! The weight was soon taken off when he was able to move about again.

Late in 1919 Jack went to his work at Richardson and Company at the Port and did all the jobs he was supposed to do first thing in the morning, then was told he could go and see the ship Pamir coming in to port. He hopped on the old office bike and rode to the wharf, stopped alongside a stringer and as he put his left foot over the bar of the bike it caught on the bar and over into the water he went. He swam to a pile, put his arms round it and surveyed the scene. No-one saw him fall, but the Te Aroha, one of the coastal boats, was berthed about a hundred feet away, and Mr Jackson the engineer, a negro and a very fine family friend of ours, was reading the paper on the after end of the ship. Jack called to him several times and when at last Mr Jackson heard the calls, he grabbed a rope, ran along the wharf and threw it down to Jack. By this time half a dozen or more men arrived, and a very embarrassed lad was pulled up on to the wharf. He hopped on the bike and pedalled home dripping all the way. Poor Mum had quite a job finding clothes for his return to work as in those days we had very few clothes.

Jack also had two motor bike accidents. The first was when he was riding home from Rongotea – near Palmerston North, with a friend as pillion passenger. Coming down the Sanatorium hill in Waipukurau, the bike skidded round a bend and Jack and his passenger were thrown. They were both dazed, and Jack said when he came to he was on the bike again. They found a doctor’s residence but the doctor was out, so his daughter, Miss Read, took them in and cleaned faces and hands. Blood was everywhere because Jack had taken a lot of skin off his face and hands. Miss Read gave the boys a meal of scrambled eggs, and when her father came home he said the best thing was to leave the raw parts uncovered so the air could dry them. Jack also had a good lump on his head where he had hit the bank. It’s not hard to imagine Mum’s reaction when he walked in home!

The second accident was at Westshore. Jack was giving the same friend a ride home after cleaning out a bach, and they wanted to clean up before going to a dance at the Sailing Club that night. As they were riding along the highway at

Page 17

Westshore, a car coming towards them was passing a horse and trap. Jack made sure the car would move back to its right side of the road, but it didn’t and he hit the car head on, or rather the car hit the bike. His passenger went right over Jack and landed on the bonnet of the car, but Jack was still on the bike. The handlebar had punctured his stomach, his upper leg was grazed and these injuries kept him home from work for a week. The car driver explained later that the person with the horse and trap was known to her and she knew the horse shied at cars. Jack and his friend consulted a well known solicitor who advised them to accept what the ladies had offered, so all they got out of it was a new pair of trousers for his friend, and the bike repairs were paid. After these episodes Dad spoke to Jack and told him how much Mum worried every time he went out and suggested he get rid of it. This he did, much to Mum and Dad’s relief.

In 1921 or thereabouts, there was a Battery Camp at Eskdale, and Jack and Reg were there. They slept in bell tents and had four eighteen pounder guns and six horses with them in camp. One night the rain came, accompanied by thunder and lightning, and they finished up with 16 inches of rain in 24 hours. They were up early in their swimming togs digging a trench round the tent to keep the water out when the order came to abandon camp as quickly as possible as the river was about to burst its banks.

They had only just had breakfast and gone out of the marquee when lightning struck the iron pin on top of one of the wooden poles. The pin was driven down through the pole and sent hundreds of splinters through the big tent. What a blessing no one was there.

About a dozen of the boys walked home sometimes up to their armpits in flood water. Cattle and sheep were being carried down the valley and drowned. The boys had to feel their way out on to the road and once they reached Petane were OK. Later, quite a number of them were asked, and went out, to clean things up after the floodwaters receded. All the tents were demolished and covered in silt. The canteen was all buried, and they had to dig up out of the mud all the tinned provisions!

The six horses were drowned and the guns were rolled over and over and half buried in silt. Jack’s pyjamas were found up a tree a couple of miles down the river. The camp piano was found pushed up a tree a long way from the camp site. The worst job they had to do was to bury the horses which had “blown” as Jack said – ‘stank to high heaven’. They had to work right alongside them because they were too far gone to be moved. They also shovelled out several hundred feet of mud and silt from the houses of nearby residents. They all slept on the floor of the Eskdale Hall and one night four of the boys decided to help themselves to some water melons growing among maize on a nearby property. They took an army great coat to carry the melons, and they had to feel their way as it was pitch dark. They duly collected a dozen or so melons and carried them out to the road by holding on to four corners of the coat, then broke a melon on the road, struck a match and much to their horror it turned out to be a pie melon! All the rest were the same. One of the boys kept on[e] and as they entered the hall he bowled the melon down the centre of the hall. As Jack said, “All hell was let loose” and they just had time to dive under their blankets before the officers came in, and switched on the light. They wanted to know what the trouble was but of course no one owned up. The boys then had to undress and get into their pyjamas after the lights went out. We used to hang on to Jack’s every word when he was telling us.

Page 18

Reg had the worst accident of all the family. When he was about six he was watching Dad put a new handle in an axe and when Dad was hammering the head of the axe off the broken handle, a piece of steel shot into Reg’s left eye. He had a dreadful eye and was home from school for nine months. When the accident happened, a young doctor said the eye should be removed, but an elderly doctor said he could save it, and his treatment was successful. When Reg went back to school the Headmaster let him skip primer three so he could be in the same class as Jack and they could do their homework together.

Reg wasn’t allowed to read much, so Dad and Jack would read all the homework out to him and he would memorise it that way. When he went to India in 1933 on transfer with the South British Insurance Co. for which he worked, his eye gave him a lot of trouble and on more than one occasion he had to stay in a darkened room for long periods.

How terrible it must have been for him having to be indoors in that heat and listen to the mosquitoes trying to get through the netting. He came back to New Zealand and after four years had to have his eye removed because it had ruptured. He didn’t have any sight in it from the day it was injured, and incidentally the piece of steel which hit or went into his eye was never found. Reg only occasionally read a book as he found his clerical work during the day and the daily paper were sufficient strain for his good eye. He had a glass eye which had to be removed and cleaned every night and if it got chipped at all it caused nasty ulcers. He later had a plastic eye and was able to drive cars from 1924, and although he had restricted vision he participated in rugby, tennis, athletics, swimming, rifle shooting, duck shooting and bowls, all after leaving college.

When Maisie was only three months old she was lying crying in her cradle when all of a sudden there was quietness. Mum went to investigate and found Jack, aged two, had put a pillow over her face and when Mum grabbed the pillow the baby’s face was quite blue. Jack, who could talk well at a very early age, looked up at Mum and said, “We don’t want her, she cries too much.” Mais also had a very bad time when aged about 20, when she had her tonsils and adenoids removed she came home from hospital but during the night I heard her weeping and on investigation found she was bleeding badly and in great pain. Mum called the doctor who returned her to hospital where because of the haemorrhaging she had to have her nose plugged. She was quite ill, but recovered quickly even after losing so much blood.

Bert had three bad mishaps, one incident affecting him all his life. Mum used to make a drink called Boston Cream which had citric or tartaric acid in it. To make a fizzy drink we put a little Boston Cream in a glass, filled it with water, and added about half a small teaspoon of baking soda. It fizzed beautifully and we all loved it. One day when Bert was about four years old he wanted a drink. He poured himself some Boston Cream, then, knowing something was added to it to make it fizz, he climbed on the bench reached up to a high shelf and got the tin of caustic soda and proceeded to put some in his drink. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture what it did to him. He screamed of course and was violently sick which undoubtedly saved his life.

Mum had to run to a friend’s place down the road where the nearest phone, was located, to telephone the doctor, who when he came said the vomiting had saved Bert‘s life. This accident has affected him all his life, and he has never at any time, been able to drink hot liquids.

Page 19

Another time he fell out of a tree at the bottom of the garden, onto a corrugated iron fence, and had to have several stitches in his scalp. He was put into the wounded soldiers’ ward at the hospital, and was there for a week. Each time these accidents happened the child had to be carried to the hospital as there were no cars available then. Later when he was a paper boy Bert had water on the knee very badly, and I did the paper run for him. One wet night a man was waiting at his gate and gave me 2/6d (25 cents saying “There you are son”. I didn’t tell him I was a girl. With Bert’s rain coat and hat on no-one could tell.

Fred was very ill after having his tonsils out when he was three. Three of us went into hospital together, Fred, Nancy and I to have tonsils and adenoids removed and for some reason the children’s ward was closed. We were put in a very large dreary basement and in the middle of the floor was a great long table on which were many many wooden arms and legs the memory of which I can never forget. They were such a gruesome sight in the dim light in the middle of the night. Why they hadn’t covered them I wouldn’t know. I was twelve at the time, Nan nine, and Fred three. Fred had to be left behind when we came home as he was quite ill. By that time (after three days) the children‘s ward was open again and he was taken there. Poor little chap how heartbroken he was when we had to leave him behind. He was a very happy little boy when he was brought home a week later.

Peg had a nasty accident when she was about four years old. Mum was in the Maternity Hospital having Dick – baby No. 12. I was fifteen or sixteen at the time and was minding house. Peg was running up the concrete steps at the side of the house when she tripped catching her face on the edge of the step, and split her upper lip from nose to mouth. Oh what an awful fright I got and what a gash it was. I had no idea what to do for it apart from putting a pad on it, and fortunately Dad arrived home from work at that very moment, so he picked Peg up and literally ran part of the way up the hill and to the hospital, where she had to have several stitches to her lip. The scar is still there, very faintly. Peg also fell out of a tree at one of our New Years Day picnics, and a wonderful friend who was a nurse, just sat beside her and bathed and bathed the bruises for what seemed like hours. Peg suffered very few after effects and Mum was sure it was due to Mrs Norman’s wonderful care.

Eric didn‘t have any accidents when young but had some heart trouble he reached fifty, then at the early age of 56 when out on the farm with his daughter, he lifted a gate off the truck and collapsed and died immediately. We were all devastated. He was the first of our wonderful family to die.

Dick – the youngest – was very ill with jaundice and had to be left in the Maternity Home after Mum came home. How very worried we all were about him as he very nearly didn’t survive. But he did! When he was about four he rushed out of the bedroom and bumped into a table in the hall splitting his head badly right between his eyebrows. How quickly accidents happen. The butcher was at the door at the time and told Mum he didn’t know a child could lose so much blood and live. He couldn’t help with transport, he just had his horse and cart. How fortunate we were that we lived so close to the hospital. Yet another accident befell Dick when Dad was turning part of the front verandah into a lovely porch. Dick was about seven, standing watching Dad high up on the ladder when the level slipped out of Dad’s hand and landed on Dick’s head causing another nasty gash which had to be stitched! He still has a ridge on his head from that wound.

Page 20

No wonder Mum said ‘you die a thousand deaths with every child you have’. She was about right.

One thing, not one of the twelve ever had a broken bone.

I was next in line and I‘m afraid I caused my parents an awful lot of worry as I was a very delicate baby. (One would never think it to look at me now!) I had projectile vomiting, (which also has a very high sounding technical name) and every scrap of food or milk seemed to be returned. I was apparently so thin that Dad carried me around on a cushion as he felt I would break because I only weighed 9lbs at nine months. Three times the doctor said I couldn’t possibly live through the night, but with Mum’s wonderful nursing I pulled through, Dad told me that many times he said “Mum was quite wonderful and pulled you from death’s door”. One day an elderly nurse who lived up the road asked Mum to try Slippery Elm compound and from the moment of the first feed my tummy accepted it and I wasn’t sick again. The slippery elm apparently relined my tummy. Unfortunately the nurse asked Mum not to tell the doctor as she said it was more than her job was worth to offer advice against the doctor’s. He said it was an absolute miracle that I recovered and he couldn’t understand it at all. What a pity it was because if he had known about the Slippery Elm it might have helped save the life of some other baby. When he asked Mum what she had given me she just told him she’d given me ‘Groats’ which was a type of baby food in those days.

As a schoolgirl I was prone to heatlumps (hives) and these when scratched turned into nasty festered sores. One year I was home for just on three months with these sores and at one time had as many as seventeen festered places on one leg. The doctor came quite regularly and he told Mum that he’d always thought only dirty children got sores but he said that now he knew better.

Tom was lucky to escape very serious injury when one day he was running up the three steps on to the side verandah and missed the second step. He fell with great force landing on his chin and had a very nasty cut which needed several stitches. Another day he was helping with the digging in the garden and when he went to put his foot on the spade it slipped and the sharp edge of the spade caught his leg and made a horrible gash. It was an awful injury, needing several stitches at the hospital. Mum’s acceptance of these traumatic situations was quite remarkable.

Nan was always very quick in her actions and one day Dad asked if she would go to the workroom under the house to get a certain tool. She ran off down the path and through the door along to the workroom and on the way caught the side of her head on a large nail from which a spade was hanging. There was lots of room, the passage being nearly six feet wide, but she must have been running too quickly and caught her head. The nail missed her eye by a fraction and she had a very nasty wound which the doctor said could have been fatal.

Bet was only three months old when Mum had to go into hospital with suspected scarlet fever and was in the infectious ward. While they were in hospital the bedroom had to be fumigated and after it was done the door was sealed with a sort of tape all round to stop all possibility of air getting in. I expect the window was done too but of course I couldn’t remember that. Mum was in hospital for six weeks and had to have Betty with her because she was breastfeeding her. When Bet was about six she had a nasty abscess on her leg and had to go into hospital to have it lanced. When Mais and Bert left after visiting her one day she

Page 21

cried so loudly they could hear her all the way down the hill as they were going home. Very upsetting for them. Bet recovered well.

One after the other we all had the normal childish ailments of whooping cough, mumps, chicken pox, measles etc and what a wonderful nurse Mum was. Nothing seemed a trouble to her – rubbing chests when we had a bad cold, dabbing itching spots, making tea or mutton broth, sponging hot little bodies and such like and generally looking after us.

When five of us had chicken pox Mum was up to us quite a bit in the night soothing itchy spots etc. and someone suggested giving us half an Aspro each. She had never used drugs but thought she would try the Aspro and at three o’clock in the morning rushed out of bed to go and look at us as she hadn’t heard a sound and she thought she had killed us all!!!

Her endless patience was displayed more than ever when we were ill or ‘off colour’ as she called it. She had some wonderful cures. If we had a cold she would sit beside us and rub chest and back for at least a quarter of an hour with camphorated oil, and I remember how her ring hurt us when using her left hand. Then we were dosed with home made cough mixture made by Mum and Dad. I can’t remember the recipe but know it contained caragene and solazzi liquorice which were bought from the chemist.

In winter time we had sulphur and treacle every week for a while – one teaspoonful at a time – and in the spring were given spring medicine made from 1 packet of Epsom salts, one teaspoonful of Tartaric Acid and one lemon cut up and a pint of boiling water added. We were given an egg-cup full each morning, and if we didn’t like it we had to hold our noses to drink it. In the early days sulphur was added to this too but left out later.

During the flu epidemic in 1918 Dad would make a cone of paper once a week, pop in a little sulphur, then putting the wide end into our mouths blew the sulphur down our throats. It was awful but I’m sure it must have saved us from getting the flu badly. I remember we had bluegum sprays hanging above our beds but don’t remember if it was to keep the flies at bay, or what it was for.

A great cure for a baby’s chapped bottom was having Vaseline rubbed on then dusted with cornflour. This was a never fail cure and so very soothing. In fact it is a good cure for chapping anywhere for adults or children.

When any of the babies had colic and there was no magnesia in the house, Mum’s cure was to pour boiling water onto a blackball in a saucer then when cool teaspoon the peppermint mixture to the baby. Very effective it was too.

Eucalyptus was a great standby for colds and wonderful for helping children and babies to sleep when they had a cold. Mum would pop a drop of Eucalyptus on her finger and just dab it on the baby’s nightgown or dress. When we were older a teaspoon of sugar with one drop of eucalyptus on it was given and a great help it was too. Too much could choke a child so it was measured very carefully. For sore throats we had to gargle with salt and water or condy’s crystals in water, and of course there was always Mum’s and Dads home made cough mixture.

For dysentery (when we were very young) white of egg was given as a cure, then later on we had to take that awful castor oil which is not recommended now. Later still we had boiled milk with a lot of honey in it.

The milk was boiled very hard, then a tablespoonful of honey added. It was awfully sweet but very effective, and this together with grated apple gone brown.

Page 22

has been our cure throughout our lives. Mum’s brother Dr Charles Jubilee Rolls, (born the year of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee), was a missionary in Abyssinia and he told her that dysentery was almost unknown there. One time a white woman arrived in Abyssinia with dysentery and she was gravely ill. Specimens were sent to the laboratory at the hospital and they were fed with sugar, but one day one of the assistants couldn’t find the sugar so fed the germs with honey and they all died. They gave the sick woman boiled milk with lots of honey and she was soon well after having been desperately ill. Apparently in Abyssinia people used a lot of honey. It would be interesting to know if this was still the case.

Several of us suffered with very bad leg ache at times – called growing pains in those days – and even in the middle of the night Mum would come and rub our legs with embrocation until they were better. They seemed to get better quickly and I’m sure the psychological effect of having someone awake and doing something about the aching legs helped in the healing almost as much as the rubbing did. Mum was a very light sleeper and would waken if one of the children were crying quietly.

A tiny lamp was always left burning if a child was ill and this was a great comfort when lying awake in the night.

If a baby or little one was ill, the cot which Dad made large enough to be used even for a five year old was taken to the kitchen during the day so whoever was ill could be near Mum while she was working, and this saved her many thousands of steps to the bedroom.

One time when I was working I remember having a very sore shoulder and somehow the typing at work seemed to aggravate it. In the evening Mum would prepare a bucket of soapy water with Sunlight soap and had me put my arm in as far as it would go, then she would bathe my shoulder for quite a long time, and after that rub it with liniment for about 10 minutes. After three days it was completely cured. She was never in a hurry when it came to doing something to help us.

After the war when my brother-in-law Mick returned from overseas, he suffered from migraine headaches and Mum would get a basin of hot water with a tablespoon of mustard in it and get him to put his feet in this while she or Bet put cold poultices on his forehead. This treatment was very effective in relieving the migraine. I think I remember Bert having the same treatment.

Quite often at our New Year’s Day picnics, or when we had been to the beach for the day, we got rather sunburnt and the cure was to mix oatmeal with water and dab it on face, shoulders and arms, or rub the affected part with cucumber. Both treatments when dry felt awful and made our faces feel as if they had masks on but they certainly “did the trick” as Mum used to say.

Mum used to say that “Mothers die a thousand deaths with every child they have”. With the accidents, sicknesses, and narrow escapes we had I think she was about right.

Page 23

TWO WORLD WARS

I was about five or six when Dad’s brothers Harry and Fred went away to the first world war and when Uncle Fred came in to say goodbye, everyone was being very brave until I suddenly put my arms round his neck and said’ “Please don’t go Uncle, please don’t go.” This completely upset all the plans for a nice bright farewell, and everyone was crying in the end.

Uncle Fred was wounded when a piece of shrapnel severed the main artery in his thigh and his leg had to be amputated, just before the Armistice, and he died when Grandma and in fact all of us were awaiting news of his homecoming. It was a very sad time for all the family.

I remember Armistice quite well when I was eight, and all the boats at the Port were blowing hooters or whistles or whatever they blow, trains tooted by blowing their whistles in a hip hip hooray way, and the church and fire bells rang out. Mum gave us old tin trays and wooden sticks, and one of us had the family bell and what a merry noise we made – all standing on the front verandah. Every few moments we’d stop our noise to listen to that coming from just about everywhere.

When the celebration of the Armistice was held in town a day or two later I remember so well going to town and Nan and Bet being dressed in pretty little white dresses and we all had red white and blue ribbon tied diagonally from shoulder to waist across our chests. I remember the crowds of people, the red white and blue everywhere, particularly on the trams, also the band and the singing. What a gay scene it was.

I remember all the war songs Mum and Dad used to sing, but one in particular Mum sang and that was:

Knitting, knitting, knitting, with the khaki wool and grey:

Mufflers, socks and balaclava caps and knitting day by day.

Knitting, knitting, knitting, with a prayer in every row,

That the ones they hold in their hearts so dear,

May be guarded as they go.

I used to love that song and always pestered Mum to sing it.

The second world war affected us all personally as Fred and the four girls’ husbands went overseas.

Jack was turned down because of his foot, and Reg couldn‘t go because of having only one eye, but he served in the Army for three and a half years in a clerical capacity. He worked in the orderly room in camp and in the Area Office.

Bert had an important position in Auckland and couldn’t be spared. Tom was ready even to being on the train but was taken off and not allowed to go because of a foot defect. Eric was in the Army, then transferred to the Air Force and was very disgusted when they kept him in NZ as an Instructor. Dick was too young to join up.

My husband, who was a Chaplain, went away with the first Echelon in January 1940, first going into camp in September 1939. When he arrived in Camp no one seemed to expect him, yet he’d been asked to go, and for about two weeks he wandered about without a uniform and without a job. He found it very frustrating.

What an awful time it was with all the men going away. In 1940 on Christmas Day the Prime Minister asked if we would tune into our radio station for a

Page 24

nationwide toast to our boys overseas, which we all thought a wonderful idea. We put the photos of our men who were away, on the table and as soon as the Prime Minister started to speak we knew it was going to be hopeless. Bet had to leave and go to her bedroom because she was so upset, then followed Mais to try and help her, then Nan had to go, then I went and we were all weeping. None of us were there to hear the toast or to drink it. Apparently the whole idea was a disaster because all over the country people were weeping just before dinner on Christmas Day. The thought of the toast was such a lovely idea but put into practice it was an absolute flop. Needless to say it wasn‘t tried again in the years following.

What lots of knitting and baking we did to send overseas to our boys, and what endless letter writing went on. We spent our evenings knitting or going to the movies and at the theatre it was awful to see so many women and girls without their escorts.

In 1942, after being away for two and half years, my husband Claude was asked to go as Chaplain on the hospital ship Oranje, and my joy knew no bounds when I realised they would be calling at New Zealand.

One day I received a telegram advising me to go to Wellington by a certain date and to be prepared to wait awhile as the Oranje would be coming in some time, but security wouldn’t allow the date to be known. Our little daughter Margaret and I were booked on the service car one Monday and on the Sunday when I was packing, the telephone rang and it was Claude. They had arrived in Wellington earlier than expected and would be there only one night. It was wonderful the way the family got into action and how all neighbours rallied round even to offering money for me to go to Sydney on the Oranje with Claude. We rebooked our seats for the car for 1 pm that day giving me just an hour to get packing finished and ready, and family and neighbours gave me sufficient money to go to Sydney, but when we reached Wellington we were advised that this wasn’t allowed in wartime. After seeing the ship off the next day I felt so wretched it would almost have been better if it hadn’t been in at all. When the Oranje went back to Sydney after that first trip of one night here, they spent thirteen weeks in Sydney and Claude had nothing at all to do apart from going visiting, visiting Scout groups, and taking some of the Javanese boys who were crew members, out for the day. These boys were given very low wages and had scarcely any pocket money and Claude found the bus companies and lots of business people were so kind to them when he explained their circumstances, so he was able to take them on several outings.

While he was in Sydney after one visit of ten days to New Zealand, Claude visited a boys’ school and while playing with the boys he fell and fractured his ankle, and was invalided home with his leg in plaster, and was on crutches. Everywhere we went people thought he had been wounded in the war and he was given V. I. P. treatment, particularly at the picture theatre. We were quite truthful and told what had happened but the preferential treatment didn’t stop! After his ankle healed he was sent to Linton Military camp where he remained until 1943 when he returned to his parish in Wairoa.

From the time of Claude’s first visit home until he was out of the Army there were lots of comings and goings and it was a very unsettling time. However, he was safe and that was wonderful.

Nan had been married only five months when one night that dreaded knock came on the door and when Reg went to the door he was handed a telegram to

Page 25

say Nan’s husband was missing believed killed. She was in Wellington at the time but fortunately living with Mais, so it came to Mais’s lot to tell Nan about Ron. She took the news very bravely and was quite wonderful.

As can be imagined, the news about Ron cast a gloom over the whole family. It felt just as if one of our own brothers had been killed. Just a few nights prior to this, on our way to church, we had been discussing the war and saying how lucky we’d been with all our boys away and still safe, and I remember someone saying, ‘Oh, please don’t tempt providence.”

Dad, who was ill when Fred went overseas and had been ill for quite a while, died in 1943 while Fred was away and he was the one we felt most sorry for, so far away from home and being without any family when he heard the news. I remember though the day he came home from the war. Most of us waited at home to welcome him, and when he came with those who had gone to meet him we were all standing outside the gate as the car came down the hill with the driver tooting the horn all the way, but when they drew up at the gate the car door opened and Fred burst out not looking to right nor left and he ran straight inside where Mum was waiting to greet him. It was a very emotional moment for us all and particularly for Mum and Fred. We left them for quite a few moments, then all burst in and the merriment began.

It was during the war that Dad was ill with his heart trouble and when he was able to potter around, he found a great deal of interest in lining the air raid shelter, on our side lawn, which the boys had dug when it was thought the Japanese might invade NZ. Dad spent hours and hours in the shelter lining the walls and making it very comfortable. He made a cupboard, complete with sliding doors, set into the wall, and stocked with everything necessary for an emergency – bandages, plaster, Aspros, medicines and brandy etc. He even put a small carpet runner on the floor and one of our long forms was taken into the shelter for seating. Fortunately the shelter was never used for the purpose for which it was built, so for a while it made a wonderful playhouse for children.

What a wonderful time it was when at last in 1945 we knew the war was all over and the air raid shelter could be filled in. Although by that time we were in our Vicarage in Waipukurau. I shared in the fun there must have been in filling in the big trench. That was done after V. E. Day (Victory in Europe). Then of course V.J. Day (Victory in Japan) came later. What wonderful processions there were, and what merriment there was at those times.