- Home

- Collections

- VOGTHERR GE

- Full Story of the Great Earthquake Disaster, The

Full Story of the Great Earthquake Disaster, The

“THE WEEKENDER” Overseas Edition

The Full Story of the Great Earthquake Disaster

At Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand

On 3rd February, 1931

Illustrated with

28 Pages of Special Photographs

Taken at the Scene of the Destroyed Towns

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE MAP

Price 1/6

This Edition cannot be sold outside New Zealand.

The Weekender

The largest circulation of any weekly paper published in the famous Canterbury District, New Zealand.

Special Overseas Edition. Price Three Shillings.

Office: 97 Gloucester Street, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Advertising Rates on application. Registered for transmission by post as a newspaper.

Great Earthquake Disaster Costs Many Lives

Towns Crumpled to Ruins in Ninety Seconds

Full Story of Greatest Disaster in Southern Hemisphere

Out of clear, blue skies and into a scene of peace and content Death stalked in frightful wrath through smiling Hawke’s Bay district in the North Island of New Zealand on the morning of February 3rd, and left behind a wreckage that has stunned the most casual by its tragic suddenness.

One moment day by day business was moving through its routine; the next, where there had been jest and laughter, Fear stalked, chilling the hearts of man, woman and child, and sending them shrieking and screaming through a whirlwind of crushing masonry and heaving, rocking ground. Where there had been love and happiess [happiness] and all those little things that go to make life, there was only terror gripping the imagination; chaos wrenching and tearing families apart. There was awfulness.

Now that some time has elapsed it is possible to give a coherent account of the disaster, and in the following pages this will be found, together with a special reference map and photographs showing in detail something of the completeness of the disaster.

THE FULL STORY.

Shortly before eleven o’clock on the morning of February 3rd, an earthquake was felt over nearly the whole of the southern half of the North Island, and extending as far south as Invercargill, in the South Island. The shake, apart from the devastated areas, was felt as a steady roll, buildings in Wellington swaying under the pressure.

A few hours afterwards the news was flashed through the Dominion that the worst earthquake in the history of the country had occurred and laid in ruins the thickly populated towns of Hastings and Napier, besides affecting many smaller towns in the same district. Following the shake, fire broke out and swept through the business sections of both towns.

Wild rumours were circulated as to the number killed, and during the afternoon it was generally accepted as a fact that over 1000 deaths had occurred. This was corrected by a wireless report from H.M.S. Veronica, which was lying in Napier Harbour at the time, and the morning papers carried the information that there were 100 dead and 1000 more or less seriously injured. All regular communication with the devastated towns was cut off, and had it not been for the connection maintained by amateur wireless operators, the dread would have been much greater.

The following message, sent out by the Chief Postmaster at Gisborne, on the afternoon of the disaster, gives a graphic indication of the position as sensed by those in the towns, and its effect on the people of the Dominion can be readily imagined:-

“Local broadcasting station has picked up message from Postmaster, Hastings, as follows:- ‘Hastings, half town in ruins. Number dead. No outlet north or south Hastings. Gangs of men out on lines now. Napier said to be worse than Hastings. New Post Office down. Bluff Hill down. (No authentic news Post Office.) Post Office tower down. Staff safe. One body woman visible; may be more. Roach’s shop down and burnt. Several dead. Library down. Dead bodies recovered. Gill’s Auction down. Gill dead. Assistant dead. Grand Hotel down; proprietor missing. Water and light cut off. Committee formed rationed food. Police formed gangs organise clear up, etc. Weather fine. Shakes are almost continuous and are continuing.”

Dead Lie in Streets.

During the day and through the evening further details of the completeness of the disaster came to hand. Interviews with some of those who had been in Napier were secured. Mr. S. Lewis, of Sydney, told his story briefly, but with dramatic reality. He was in his car outside the Post Office when the ‘quake came.

“All of a sudden the car shook violently,” he said. “I jumped out to see what was wrong, but fell over. On looking up I saw all the buildings opposite collapsing. Then clouds of dust enveloped the whole place. People were rushing about screaming. No one knew what was going to happen next. Thousands rushed to the beach. Every two-storeyed brick building came down. All the asphalt roads buckled up.

“People were lying dead in the

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

WHITE LIGHT OF COURAGE.

Out of the crumpled fire-swept chaos come vignettes, each of which is a wonderful story of the heroism that lies deep buried in the souls of all mankind.

In one awful moment the Nurses’ Home at the Napier Hospital was crushed, killing many of the Sisters and nurses sleeping in their quarters after coming off night duty. Through the remains of the institution terror spread its cloak. And yet, in that moment, palpitating with fear, those of the nursing staff who lived had no thought but for the unfortunates lying in their beds. Through the haze of dust, through the shambles amongst which lay their friends, went girls and women, living up to the highest traditions of a profession that has been world-honoured, and will be as long as humanity survives.

It is not much to say in cold print, but when you stop to think that women could go through this, putting all to one side that they might carry out into the open the patients they had been nursing, it is something so big and so wonderful that it shines through the dark clouds of disaster like some great shaft of clear, white light.

streets. Women rushed about in hysterical condition, while thousands, on reaching the beach, entered the water.”

When the ‘Quake Came.

Rushed immediately to the scene, a special reporter from “The Dominion,” Wellington, told the story of the happening. His account read:-

Shrouded with a pall of evil-smelling smoke, Napier has become over-night a skeleton of its former self and the grave of what remains an indeterminate number of its population of 20,000 persons. With one gigantic sweep the earthquake has reduced the whole town to a heap of ruins, still blazing and crumbling at each shake.

The population has become a community without a home, without food or water, and for the most part without shelter. In one moment, so sudden was the visitation, the population was divorced from its town, to become, as it were, a thing apart from the roaring mass of buildings that joined in one great conflagration from end to end of the business area.

Napier as a town has been wiped off the map. To-day it is a smouldering heap of ruins, the sepulchre of a prosperous port, and the gaunt remains of a beautiful seaside town.

The face of the Bluff (a famous hill) has come down across the road to Port Ahuriri and blocked access to it by land as well as by sea, at least for the moment. The whole face of Hospital Hill and the other heights behind the town have crashed on to the buildings below. Not a building in Napier has escaped damage. Houses have lost chimneys or whole sides. Streets have been torn up like bililard [billiard] cloths ripped by a sturdy cue, and telegraph poles have been thrust at a crazy angle over every road, with wires tangled and hanging from wrecked buildings like charred serpents suspended from the last branches of a brick and concrete forest.

The accounts of those who were in town at the time of the upheaval show that the movement of the earth was almost vertical, and that the whole area was forced upward for several feet with one terrific jerk, to subside with a sickening jolt.

As appears to have been the case in other parts of the stricken district, the upheaval came like a flash and left behind it a trail of ruin within a few seconds. At 11 o’clock in the morning shops and offices were full of people. There was an immediate rush for the streets, but those who gained them were in many instances buried as they reached the footpaths.

The whole of Napier was deafened with the roar of falling masonry. Then a strange silence followed for a space. Suddenly recovering from their terror, the people raced for the foreshore, to avoid being trapped by still crumbling buildings. Even on the beach the sight was terrifying. The sea washed away from the beach for hundreds of feet, and then rolled back. At the same time the Bluff roared over the road at its foot. Rocks that before had never appeared above the surface came above the water level, the whole seafront rising about 8 or 10 feet.

Appalled, the residents of Napier gazed in horrified amazement at the destruction. The hills behind the town were crumbling away in clouds of dust, whole sides of houses high above the shore were being torn away, and on the flat huge tongues of flame were appearing from every direction. The town was immediately isolated from the outside world, and Napier was left a blazing ruin to witness the burning of its very heart for a day and a night.

Services Organised.

With the earth still shaking under their feet and with the blazing ruins surrounding them on all sides, doctors, nurses and others, rushed to the scene by special aeroplanes, organised the work of rescue, and dressing-stations sprang up almost instantaneously. Uninjured men in the stricken areas and those able to move about were organised under the direction of officers from the warships in post [port] and a beginning was made to ascertain the real extent of the damage.

It was only when a systematic search commenced that the extent of the death roll [toll] was realised, and whereas a hundred was thought to have covered the whole area, it was soon discovered that this figure would be exceeded in Napier alone.

Day and night the searchers continued their grim task among the ruins. The details of what they found in many instances are things that are better not placed in print.

The call sent out for motor-cars to convey the women and children away from the stricken area was responded to by the countryside, and there was a constant stream of traffic moving along the roads that were undamaged.

One man whose wife had been in Napier walked the sixty miles to town in a frantic search for her. His feet were bleeding when he arrived, but he did not rest until he had discovered her – in the hospital, having just given birth to a child.

Stories of frantic searches ending in relief at the finding of dear ones or tragedy at finding them gone or “missing,” continue to filter out from the devastated areas. At the Parke Island Old Men’s Home, Napier, James Collins, aged 90, was dug out of the ruins by a party of grave-diggers, after having been buried for three days.

Even to-day the total number of those dead cannot be ascertained, as more bodies are being found in the ruins, and there is also the fact that many are thought to have been buried under some of the hills when they slipped. Present figures give the number at approximately 250, but this will not represent the final figures.

IN THE CATHEDRAL.

At St. John’s Anglican Cathedral the shock came while the Very Rev. Dean Brocklehurst was conducting a Communion service for a fairly large congregation. The whole building, which was of brick, crumbled to the ground.

Among those present was Mrs. Tom Barry, senr. A large girder caught her, pinning her to the ground. Her son saw her plight, and did his best to release her. The efforts of others were also fruitless.

Then the building caught fire, and the flames, spreading, crept closer to Mrs. Barry. Every effort was made to save the unfortunate woman, those helping playing a hose on her and on the timber near by.

It was seen, however, that a rescue was impossible, and, as a last resort, a doctor rushed up to the agonised woman and gave her a strong injection of morphia.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

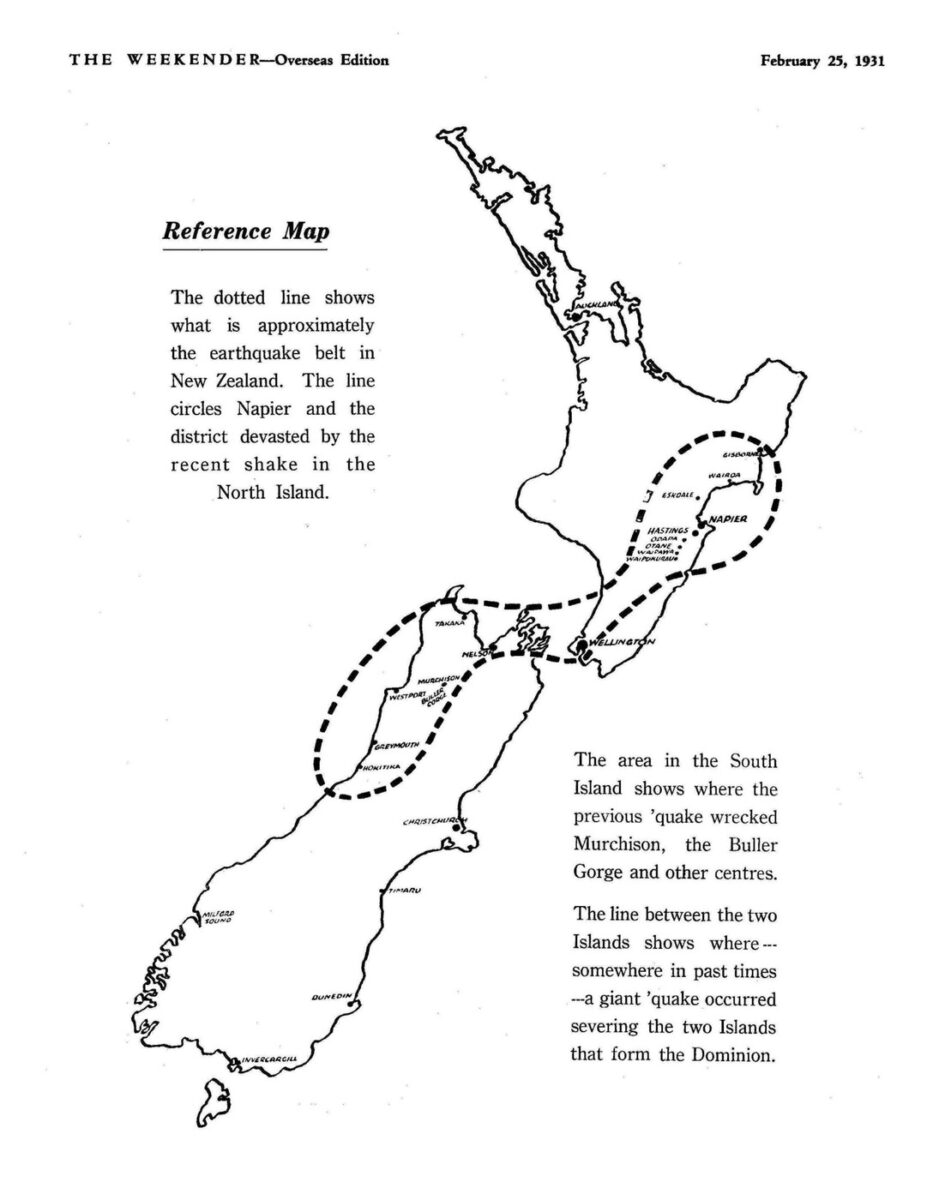

Reference Map

The dotted line shows what is approximately the earthquake belt in New Zealand. The line circles Napier and the district devasted [devastated] by the recent shake in the North Island.

The area in the South Island shows where the previous ‘quake wrecked Murchison, the Buller Gorge and other centres.

The line between the two Islands shows where – somewhere in past times – a giant ‘quake occurred severing the two Islands that form the Dominion.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – An extraordinary photograph taken a few hours after the earthquake, showing people carrying their belongings through the ruined streets. On the left is all that remains of the Empire Hotel, and on the right that of the Clarendon Hotel. Note the fierce fires raging in both views.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Reminiscent of Ypres during its last days of bombardment in the war. Note the remains of the motor car in the centre of the picture. Below shows the devastation at Port Ahuriri, with the remains of the Post Office dominating the scene, and the clouds of smoke from burning buildings shadowing all.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Hastings – Above – Wrecked premises in the main street. Centre – All that was left of Roach’s store. There were fifty people on the top floor at the time of the earthquake, and it is known that nine of the girls employed there lost their lives. Below – Odd cases of looting occurred and the picture shows the patrols guarding the ruins against further thefts.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Standing like a beacon in one of the stricken streets is this solitary cross, perhaps emblematic of the faith filling the breasts of the people who are now planning to build again on the ashes of the former hopes.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

Napier – From whichever angle the town was viewed there was the same scene of utter and hopeless desolation. All that men had worked for through the years was lost in a moment.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – An illustration giving an excellent idea of the utter wrecking of the buildings, and showing how little hope there was for those unfortunate people caught beneath the falling walls.

Napier – Picking his way through the almost blocked streets. A solitary searcher on the lookout for anyone imprisoned under the ruins of the buildings he passed by.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – After the first blaze of the fires had died down it was possible to some extent to gauge the extent of the damage. Note the debris reaching right across the street. In one instance several taxi drivers were buried under such a fall.

Napier – A close-up view of the damage done to one of the principal streets. While the homes on the hill in the background seem intact most of them were rendered inhabitable.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Another view of the Nurses’ Home at the Hospital showing the completeness of the damage. In the centre can be seen a motor car. Below – Contemplating the ruins of business premises that a short time before had represented all they had in the world.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – A task that made strong men flinch. Searching for the dead and injured among the ruins of the shattered town. Some of the victims were unrecognisable, and had to be buried unidentified.

Hastings – Many places in the town had false brick fronts. Here is all that remains of a tea room with all the tables set on the top zoor [floor]. The brick fronts fell outward, thus saving many lives.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – A mass of tangled wires and debris strewn about the streets. Another scene in the business area.

Napier – The scene immediately after the earthquake was beyond description. Here is a street – at one moment bordered with handsome buildings – the next strewn with bricks and masonry beneath which people and motor cars were buried.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – This great building towered up, massive and impressive, but in three or four minutes it was smashed and torn about as it shows in the illustration. Below is a scene in the town shortly after the upheaval, knots of residents contemplating the damage.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Hastings – Above – A view looking along one of the principal streets in the town taken shortly after the earthquake. Below – Here was a beautiful home with a motor car standing out in front. Today this is all that is left of it.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Looking along Marine Parade, once the pride of the town. The photograph shows the remains of Messrs. Murray, Roberts and Co., Ltd’s building and that of the Y.M.C.A. Bluejackets from the warships can be seen searching among the remains for bodies.

Napier – In the foreground can be seen all that remains of the fine memorial erected to those who fell in the Boer War. At the back is all that is left of a fine building.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – After the fires had died out. The main business areas, where it was estimated that the damage will reach in the vicinity of £9,000,000.

Hastings – Looking from Russell Street along the length of Heretaunga Street. The buildings on the left-hand side of the photograph have been completely wiped out.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – In the track of the earthquake. After the shake that brought handsome buildings to the ground, fire swept through the devastated area. Above shows the smouldering ruins of business premises, and below one of the the principal streets hopelessly blocked.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Hastings – Although the devastation in Hastings was not quite so severe, the town was practically wrecked. The photograph shows part of the damage done in Market Street.

Napier – In the background can be seen the Post Office. Although the building was damaged the staff escaped, but several people lost their lives in the lobby of the building and the immediate vicinity.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Hastings – As with its sister town of Napier, the main business area in Hastings was utterly wrecked. Here is another view showing part of the wreckage.

Hastings – Here is a building at the corner of Heretaunga and Market Streets, Hastings. The illustration shows how the front of buildings was torn away, leaving the furnishing of the rooms showing to the street.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Gaunt ruins against the sky line, giving a graphic idea of how completely the upheaval wrecked buildings and strewed the place with their remains.

Napier – With their homes gone and with gaunt fear in their hearts, making them afraid to sleep inside buildings, thousands of people spent the nights on the sea shore in tents and under all manner of improvised structures.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25 1931

Napier – Nothing seemed to withstand the fierce wrenching twist. Here is what was once a magnificent building. It was reduced to this state in 90 seconds.

Napier – An odd chimney and heaps of debris are all that remain of magnificent buildings which were almost intantaneously [instantaneously] reduced to shambles.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25 1931

Napier – Giant masses of masonry were taken and thrown about as though they were pebbles. Note the two blocks in the picture above. Below is another picture taken while the fires were ravaging what the earthquake left behind in its track.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Hastings – Above – Here is all that is left of the once imposing Grand Hotel, where the proprietor and his wife both lost their lives. Below – One of the business premises underneath which many bodies were supposed to be lying.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – One of the greatest tragedies happened in this building – the Nurses’ Home at the Hospital. Here Sisters and nurses were crushed while they were lying in bed. Reference to the heroic action of those saved is made in the text at the beginning of the issue.

Napier – View of the Nurses’ Home taken from the rear showing the interior of rooms where, all unsuspecting, women and girls were peacefully sleeping when the awful catastrophe swept them into the Great Hereafter.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25 1931

Napier – The Marine Parade, where on Sundays thousands used to stroll their way through the quiet hours of the afternoon, was turned into a shambles of flying bricks and timber. The photograph shows the view looking north.

Napier – In the heart of the business centre. Great, gaunt shells are all that remain of once fine buildings, the site of many of which marks the tomb of some unfortunate.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Day after day the grim task went on – a task that brought home with full realisation the terror, as body after bodies – those of men, women and little children – were recovered and removed for identification purposes. In many instances there were only pitiful heaps of charred bones.

Does this make you realise what such a disaster means?

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Above – This illustration shows with extraordinary clearness the way in which the earth was twisted and torn. In some instances motor cars running along the roads were trapped in the crevasses that opened up suddenly. Below – The remains of the band rotunda on the Parade. This is another illustration that shows how the buildings were suddenly lifted up and then, as suddenly, dropped. Note the spread of the posts.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

THE WEEKENDER – Overseas Edition February 25, 1931

Napier – Looking down Hastings Street, where the wreckage completely blocked the thoroughfare. On the right is all that is left of the Bank of New Zealand building.

Napier – All that is left of the Provincial Hotel. What would have happened had the shake occurred at night when the bed-rooms were all occupied is too terrible to contemplate.

– “Weekender” Photo, Copyright.

Printed by the Civic Press, Wellington, New Zealand, and published by Jesse Barnes, of New Brighton, Christchurch, New Zealand, for the proprietors, The New Spectator Co., Ltd., 97 Gloucester Street, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Subjects

Tags

Format of the original

Book paperbackDate published

25 February 1931People

- Mrs Tom Barry

- Reverend Dean Brocklehurst

- James Collins

- Mr Gill

- S Lewis

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.