- Home

- Collections

- MILLER OA

- Gascoyne Story, The

Gascoyne Story, The

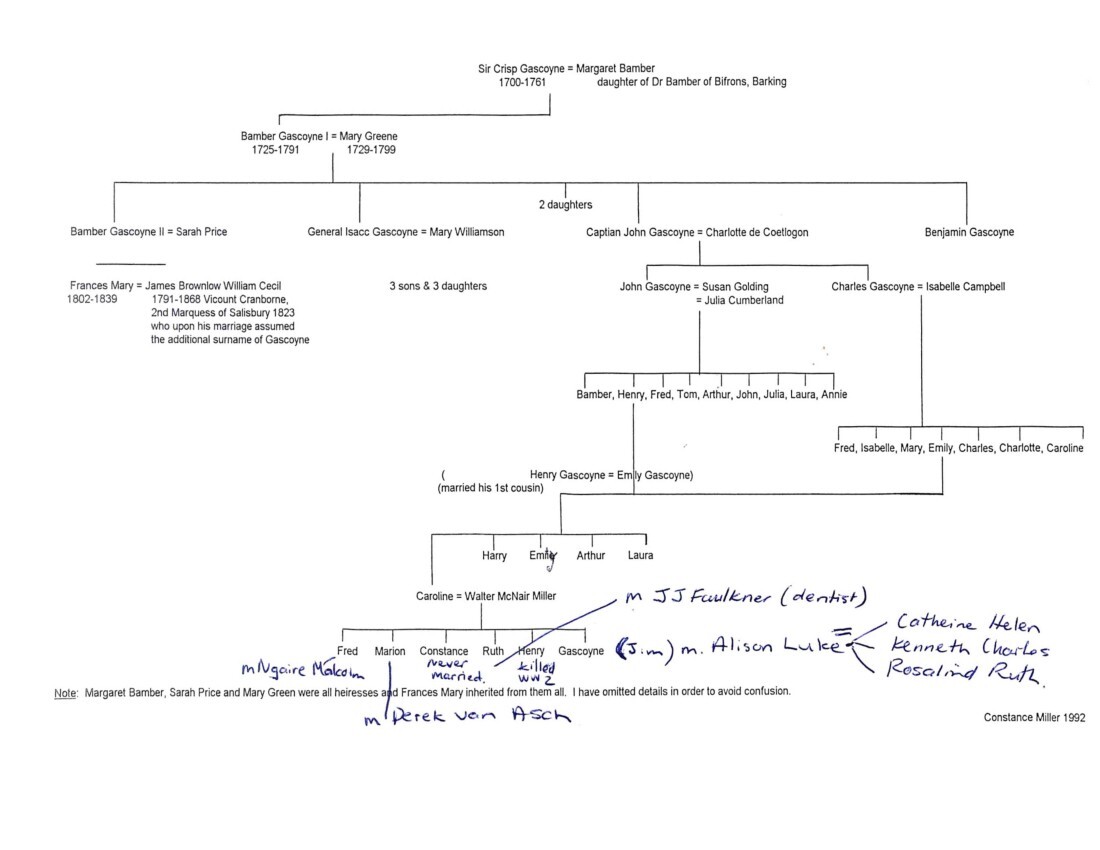

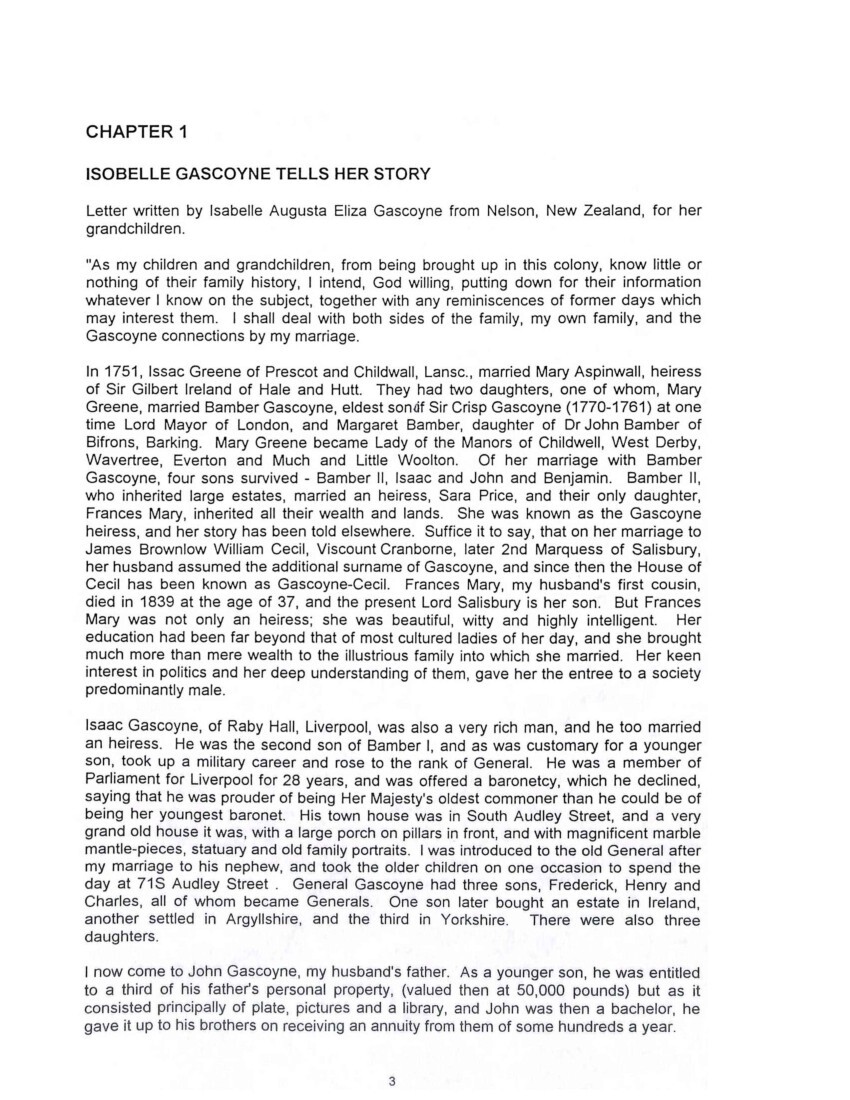

Sir Crisp Gascoyne 1700-1761 = Margaret Bamber daughter of Dr Bamber of Bifrons, Barking

Bamber Gascoyne I 1725-1791 = Mary Greene 1729-1799

Bamber Gascoyne II = Sarah Price

Frances Mary 1802-1839 = James Brownlow William Cecil

1791 – 1868 Viscount Cranborne, 2nd Marquess of Salisbury 1823 who upon his marriage assumed the additional surname of Gascoyne

General Isacc Gascoyne = Mary Williamson

3 Sons & 3 Daughters

2 daughters

Captain John Gascoyne = Charlotte de Coetlogon

John Gascoyne = Susan Golding

= Julia Cumberland

Bamber, Henry, Fred, Tom, Arthur, John, Julia, Laura, Annie

Caroline = Walter McNair Miller

Fred m Ngaire Malcolm

Marion m Derek Van Asch

Constance never married

Ruth m JJ Faulkner (dentist)

Henry killed WW2

Gascoyne (Jim) m Alison Luke

Catherine Helen

Kenneth Charles

Rosalind Ruth

Charles Gascoyne = Isabelle Campbell

Fred, Isabelle, Mary, Emily, Charles, Charlotte, Caroline

Henry Gascoyne = Emily Gascoyne (married his 1st cousin)

Benjamin Gascoyne

Note: Margaret Bamber, Sarah Price and Mary Green were all heiresses and Frances Mary inherited from them all. I have omitted details in order to avoid confusion.

Constance Miller 1992

FORWARD

It was only after Isabelle Gascoyne’s memoirs had come into my hands that I decided to put together the scraps of information I had gleaned over the years on the different members of the family from which I had descended – their background and their life in New Zealand. I had always known the old story of how, in the days of Henry IV, the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, Sir William Gascoyne, had sentenced the young Prince Henry to a short term in prison for slapping his face during a court hearing, thereby establishing the authority of the law over sovereignty, an authority that Henry IV had acknowledged; and I was fascinated, while on a visit to London, to see that the scene was depicted in a large mural behind the throne in the House of Lords. I became curious about Judge Gascoyne’s descendants. However, I decided that I would have to skip a few generations before beginning my story. Isabelle Gascoyne’s memoirs cease with her arrival in Nelson, so from there on, I had to do a great deal of research, and there are still gaps which I have been unable to fill.

I wish to thank Margaret Black for her valuable assistance with research, and my brother F W G Miller for his advice and encouragement, and all those members of institutions in Australia and New Zealand, as well as individuals, who answered my letters requesting information.

Constance M M Miller M.A., DIP. E

Hastings

Hawkes Bay

New Zealand

1992

INTRODUCTION

Most pioneer families have a story to tell, but because the members are too fully occupied or lack the inclination, many of these stories are left untold. This is New Zealand’s loss, for they are a link with Britain and her colonial past, rich with the colour and culture of other lands, and are too, part of our early history.

As I began the story of the Gascoynes who emigrated to Australia and New Zealand in the middle of the 19th century, I realized that it would be necessary to delve into and describe their background in order to give my readers some idea of the tremendous adjustment they must have had to make in settling in an entirely new environment, so far removed in every way from what they had known. Indeed I doubt if that first generation and their children ever did completely make the adjustment.

No doubt my story will be patchy. There will be gaps, incomplete picture and some omissions; but as far as possible, it will be a record of true happenings and real people as I came to know them through my study of old papers, letters, diaries and memoirs, various records and biographies, and also from the live accounts of past happenings so frequently and vividly related to me by my mother, herself a Gascoyne on both the maternal and paternal side of the family.

My mother was an exceptional character, contented, sweet-tempered, unselfish. She loved her six children dearly without being ambitious for them. She died in her 94th year, never having been in hospital or suffered a serious illness, and outliving my father by a good 20 years. My father was much more reserved and quiet, a lover of the outdoor life. Owing to his having been seriously wounded in action in the battle of Bothasburg during the Boer War, when he was a very young man, he had to spend his life in secretarial work, rather than follow his natural inclination for an outdoor occupation. He enjoyed gardening, tramping and fishing, keeping up these interests as long as his health allowed. He was the eldest son of Walter Miller, an inspector of stock for New Zealand, and a grandson of a well-known Otago settler who owned the Teviot and Roxburgh Stations, and after whom Miller’s Flat was named. But I do not intend to tell the story here of this side of the family, other than to mention the fact that they had been Scottish borderers and had their origins in the town of Roxburgh in Scotland. On my mother’s side however, I have been able to trace my ancestry back to 1700, and there begins a tale that reads like a romantic novel.

From the time we were quite young, my brothers and we sisters would listen enthralled to the scraps of stories and information that my mother used to pour out to us, stories of the past that seemed to have little relevance to our daily lives, but which we never failed to find fascinating no matter how often they were repeated. I think now, that my mother withdrew into this world of strange happenings, almost a dream world, to escape for a little while from the daily routine tasks of her life. She had not been trained to cook and sew for a big family, and she knew absolutely nothing about budgeting. What could not be paid for was simply not bought. Things were certainly not easy for her (nor for my father) but she never complained, accepting her life as it was, and was very happy. Our wise family of recent years, once said to me, “Write down everything your mother tells you about the past,” but even though one may realise that the old have precious memories and that their time is short, it is difficult to do this. We tend to shut our minds to the thought that the inevitable death of someone we love is near at hand.

Later I was full of regret that I had neglected so important a task, and that I had to depend so much on my memory and that of my sisters and brothers, and that there would be many questions that would remain unanswered.

Page 2

Nevertheless there were many interesting papers and old letters – one especially helpful, which was written by my maternal great-grandmother, Isabelle Gascoyne, to her grandchildren to explain who exactly they were, and how they had come to be living in this country.

Isabelle Campbell had married Charles Gascoyne, and her letter written in 1888, when she was 78 years old, did not come into my mother’s hands till long after my own grandmother, Emily Gascoyne, was dead. We had difficulty in deciphering some of it, but as far as possible, I shall set it down just as it was.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The name “Gascoyne” was originally spelt ‘Gascoigne’ and some branches of the family later adopted the old spelling again.

Page 3

CHAPTER 1

ISOBELLE [ISABELLE] GASCOYNE TELLS HER STORY

Letter written by Isabelle Augusta Eliza Gascoyne from Nelson, New Zealand, for her grandchildren.

“As my children and grandchildren, from being brought up in this colony, know little or nothing of their family history, I intend, God willing, putting down for their information whatever I know on the subject, together with any reminiscences of former days which may interest them. I shall deal with both sides of the family, my own family, and the Gascoyne connections by my marriage.

In 1751, Isaac Greene of Prescot and Childwall, Lansc., married Mary Aspinwall, heiress of Sir Gilbert Ireland of Hale and Hutt. They had two daughters, one of whom, Mary Greene, married Bamber Gascoyne, eldest son of Sir Crisp Gascoyne (1770-1761) at one time Lord Mayor of London, and Margaret Bamber, daughter of Dr John Bamber of Bifrons, Barking. Mary Greene became Lady of the Manors of Childwell, West Derby, Wavertree, Everton and Much and Little Woolton. Of her marriage with Bamber Gascoyne, four sons survived – Bamber II, Isaac and John and Benjamin. Bamber II, who inherited large estates, married an heiress, Sara Price, and their only daughter, Frances Mary, inherited all their wealth and lands. She was known as the Gascoyne heiress, and her story has been told elsewhere. Suffice to say, that on her marriage to James Brownlow William Cecil, Viscount Cranborne, later 2nd Marquess of Salisbury, her husband assumed the additional surname of Gascoyne, and since then the House of Cecil has been known as Gascoyne-Cecil. Frances Mary, my husband’s first cousin, died in 1839 at the age of 37, and the present Lord Salisbury is her son. But was not only an heiress; she was beautiful, witty and highly intelligent. Her education had been far beyond that of most cultured ladies of her day, and she brought much more than mere wealth to the illustrious family into which she married. Her keen interest in politics and her deep understanding of them, gave her the entrée to a society predominantly male.

Isaac Gascoyne, of Raby Hall, Liverpool, was a very rich man, and he too married an heiress. He was the second son of Bamber I, and as was customary for a younger son, took up a military career and rose to the rank of General. He was a member of Parliament for Liverpool for 28 years, and was offered a baronetcy, which he declined, saying that he was prouder of being Her Majesty’s oldest commoner than he could be of being her youngest baronet. His town house was in South Audley Street, and a very grand old house it was, with a large porch on pillars in front, and with magnificent marble mantle-pieces, statuary and old family portraits. I was introduced to the old General after my marriage to his nephew, and took the older children on one occasion to spend the day at 71S Audley Street. General Gascoyne had three sons, Frederick, Henry and Charles, all of whom became Generals. One son later bought an estate in Ireland, another settled in Argyllshire, and the third in Yorkshire. There were also three daughters.

I now come to John Gascoyne, my husband’s father. As a younger son, he was entitled to a third of his father’s personal property, (valued then at 50,000 pounds) but as it consisted principally of plate, pictures and a library, and John was then a bachelor, he gave it up to his brothers on receiving an annuity from then of some hundreds a year.

Page 4

He was at that time a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy. He afterwards married a Miss Charlotte de Coetlogon, only daughter of the Rev. Charles Edward de Coetlogan, of a noble French Huguenot family, who had been chaplain to one of the royal dukes and had fled from France with his wife and daughter at the time of the French Revolution. Mrs John Gascoyne, nee de Coetlogan, was the mother of two sons – John William and Charles Manners and four daughters. Of the latter, one died in infancy, the second at 18, the third, Mary, remained unmarried, and at her parent’s death, received a pension of 100 pounds a year from Lord Salisbury; the fourth daughter, Sophie Grosvenor, married beneath her social position, a Mr Williams, the son of an innkeeper at Bridgewater, and thereby offended her rich grandfather de Coetlogan so much that he made a new will, leaving a handsome house in London, plate, pictures and 30,000 pounds to a perfect stranger, a young lady whom he wished his grandson Charles Gascoyne to marry on his return from India, not knowing that he had already been married to me three months when he received his grandfather’s letter. Aunt Sophie had a large family. She was always her mother’s favourite, but I thought her selfish and cold-hearted and her children too. Her eldest son became a clergyman, but he was a confirmed drunkard and a disgrace to his profession. He came out to New Zealand not so long ago, and behaved so badly in Wellington that several gentlemen jointly subscribed and paid his passage back to England. Aunt Mary died some years ago, but Aunt Sophie, as I write this letter, is in her 80’s and living in London. (Author’s note: All people mentioned are long since deceased).

John Williams, my husband’s elder brother was married twice, first to an elderly widow lady, a Mrs Susan Golding, when he was only 18. She had a large fortune and a beautiful estate on the banks of the Thames. John has received from his Uncle Bamber an appointment in the War Office, but this he threw in, on his marriage, and became an idle, fashionable man-about-town, driving his carriage and four, and enjoying his new station in life. His wife died four years after their marriage, and it was then found alas, that she could only will half of her property to John, about 20,000 pounds, I believe, the rest going to her children by her first marriage. Your grandfather Charles, my husband, when a boy, paid a visit to his elder brother in his grand house in Devonshire. John was very kind to his old wife apparently, but very unwilling to let her spend any money in case she wasted it; and he used to beg her to sit well back in the carriage when they were out driving; otherwise her old face, instead of that of a young and pretty women, would spoil the whole turnout. All this however was said in joking good-humoured manner. John was the best tempered of the family, but loved money, becoming very mean and careful latterly when he had lost most of his fortune in railway speculations. But he had great charm, and a fine presence; and he married again, this time to a Miss Julia Cumberland, daughter of Admiral Cumberland. The admiral had three daughters, all good looking, but the youngest Julie, was considered a great beauty. She was called the ‘Star of Devon’ at balls, in Plymouth, where her father was in command and where your uncle met her. They married shortly afterwards and had seven sons and three daughters. The eldest son, Bamber, went to Australia and was in the Mounted Police in Melbourne and the Gold Coast. He came to New Zealand, while still a young man, because we were settled here, and very soon married. They had three children, but their young lives ended in tragedy. They were all barbarously murdered in the White Cliffs Massacre in Taranaki; and not only did the Government take no steps to punish the murderers, but about a year ago, actually pardoned the chief one and presented him with a medal for saving the life of a Maori comrade who was drowning.

Page 5

Four other sons emigrated, Frederick to New Zealand, where he died in 1882, Charles to Melbourne, dying there in 1886, and Henry and Arthur to New Zealand. Henry married in New Zealand my daughter Emily, his first cousin, and they became your parents. Of John’s daughter, Julia the eldest died at 16, Laura is now Mrs Cumberland, and Annie is Mrs Hidow. Both live in England, and correspond with us.

I now come to my husband, Charles Manners – your grandfather Gascoyne. He received a commission in the East India Company Service, from Lord Salisbury who had married his cousin and left home. His parents at that time resided in Swansea, South Wales, his father, Captain John Gascoyne holding a Staff appointment in the Royal Navy. Charles was appointed to the 5th Regiment of Bengal Light Cavalry, to which regiment my brother, Archibald Campbell, who went out about the same time, was also appointed. They became devoted friends and remained so throughout life. My brother afterwards removed to the 1st Bengal Cavalry. Before your grandfather Charles left England, being then about 18 years old, he had become engaged, but after seven years, the young lady broke off the engagement not wishing to go out to India. In 1835, Charles and I met at Cawnpore. I was on my way to join my brother at Meerut, and was under the charge of the Honourable Mrs Ramsey, wife of General Ramsay, and sister-in-law of the then Governor-General of India, Lord Dalhousie. We had a large fleet of boats going up the Ganges and halted for three or four days at Cawnpore. While we were there, the officers, among whom was Lieutenant Charles Gascoyne, gave a great ball, at which Mrs Ramsey’s only daughter Anna, and I were present. The arrival of young ladies in those days caused quite a sensation, and we were made much of, each officer trying to outdo the other in engaging our attention.

We resumed our journey to Meerut shortly afterwards, the Ramsey’s by river; but I, at my brother’s expressed wish, had had a palanquin-dawk made, for by this means I should reach him more quickly. And with a guard of two sepoys on horseback, I started on my long overland journey alone, being well provided with every comfort, wine – I remember I had never tasted Constantia before – and various other good things all placed in my palanquin by Lieutenant Gascoyne, my brother’s most intimate friend, as we parted. At 7 o’clock in the evening, after about an hour of travel, I heard a horse galloping behind the plaque. The servants were in front, so I opened the door and looked out. There was Lieutenant Gascoyne. I felt frightened at first, but he assured me he had only galloped up to see that I was safe as far as the first stage, and in case I wanted anything. Six weeks from that date we were married.

And now I go back to my own early history. My mother’s father, Major Munro, who is mentioned in the American War of Independence, as having raised a company of soldiers at his own expense to fight for England, had an American wife. They had three sons and two daughters. The eldest daughter, Annie, married Mr Pasea, a very wealthy man who owned the greater part of the Island of Trinidad. The younger, Eliza, who later became my mother, being still a child when her parents died, was adopted by Lady Heneage Osborn, daughter of the Earl of Winchelsea, and wife of Sir George Osborn, a brother officer and inseparable friend of Major Munro. Lady Heneage and her sister, Lady Helen Finch, lived in a grand old house in London, to which I, when a child, used to be taken in a queer old carriage with a lame coachman, and a hump-back footman in gorgeous livery, in attendance.

Page 6

Everything in the house looked strange to me, the drawing room full of tables and chairs with curious twisted legs and grinning monsters, and the sofas, curtains and hangings all of faded, thick blue satin damask. Lady Heneage was a dear kind old lady and very fond of me, but I thought Lady Helen stiff and cold. She always dressed in the style of Queen Anne, with her hair powdered, a gown with peaked bodice, elbow sleeves and lace ruffles, together with very high-heeled shoes. Lady Heneage dressed as a widow. They both outlived my poor mother who died in 1820, by several years. My mother received a very superior education. She became an accomplished musician, and sang Scottish songs especially well and with such expression that in India once, she fainted at the piano from the crowd that pressed round her. She spoke French fluently and also sketched well. On leaving school, she visited Scotland and there she met my father, Captain John Campbell, just before he sailed for India, and became engaged to him. The late Lord Glenely, Charles Grant, and his father Sir Robert Grant, afterwards Governors of Bombay, were related to my mother; and Lord Glenely, who was an East India Company Director, gave commissions or cadetships to my Uncle Archibald Campbell, my mother’s favourite brother-in-law, and to my father.

My mother followed my father to India about two years after her marriage, going out in the ‘Sovereign’ an East Indiaman, accompanied by her brother Archie, who would not allow her to go without his protection It was a long and rough passage in those days from Cromarty to London, and they were nearly taken prisoner by the French in 1806. My father, John Campbell of Dunstaffnage, was a medical officer, attached to the 7th Madras Cavalry, as was also my Uncle Archie. My mother remained five years in India, when her health failing she returned to England with her four children – Alexander, Archy, Osborne-Heneage and me – a baby in arms, with an Irish nurse named Bennett. She stayed in Scotland visiting Dunstaffnage and other places and finally Cromarty and Elgin. At the end of five years, in 1816, she resolved on joining my father again in India, and accordingly placed her boys under the care of a Dr and Mrs Brown at Cheltenham I was placed with a single lady at Bath, and for a child of only five years old, was very cruelly used, being forced to learn music and matters far beyond my powers or inclination. I remember when I would not or could not do my lessons she used to hold my head down in a basin of water until I was almost choked. She wished to have five more pupils but as none were forthcoming, she wrote to my guardian and took me up to London, were I was placed in a large boarding school in Cadogan Place. There I was dressed immediately in deep black and told that my father was dead.

While we were out walking one day – I was about six years old – a kind looking stout lady stopped us and asked the governess my name. Upon hearing it, she took me in her arms and embraced me many times begging that I might be sent to her house every Saturday till Monday, while I remained at school. She was a Mrs Skinner, the widow of General Skinner, and mother of three daughters. Her maiden name was McLean – she was a relative of Sir Douglas McLean, well known in New Zealand, and also a connection of the Campbells of Dunstaffnage.

After I had been at school for a year, more or less, I was roused one night from sleep, at about 9pm, taken up and dressed, and placed in a closed carriage with a footman inside, and driven a long way to Kensington, where we stopped at a well-lighted house. I was ushered into a room full of company, who kissed me and murmured, “Poor little thing”. In the morning, I was driven by my uncle to an hotel in a quiet part of London. We went upstairs to a drawing room which look very dark and dismal, for the curtains were drawn; and I saw at the far end of the room a lady in black lying full length on a sofa. In an instant I knew it was my dear mother whom I had never forgotten and had often tried to go to. She clasped me in her arms, and I would not be parted from her nor leave hold of her hand for a minute all day.

Page 7

I next recollect my brothers coming for a short time. It was then arranged that they go to a school at Putney, and my mother took part of a house, the drawing-room floor, in Lisson Grove, and sent me as a day scholar to a Miss Payton, who took pupils in a house a few doors away. My mother never recovered from the shock of my father’s death, which had occurred just as she had reached Madras. She had gone out in a ship commanded by a cousin of my father. In the “Madras Roads”, as the sea is there called, no vessel can approach the shore owing to the vast rollers, three waves in succession, which race in towards the beach. Therefore when a vessel is sighted, queer-looking natives with high conical caps of straw in which they place letters or papers, push off from the land on two logs tied together called “catamarans”. Upon the first one reaching our vessel, everyone crowded round to hear the news. Captain Campbell, not observing my mother among the crowd, read aloud, “John Campbell, Dunstaffnage, is dead. He died of Cholera after a few hours of illness caught while attending at the hospital”. My mother fainted and became afterwards very ill, for she and my father were most deeply attached to each other. Some of their beautiful letters are still in my possession.

My mother returned home and lingered for four years in Lisson Grove, where she died. She was attended by Sir Astley Cooper, Sir James Clark, Dr Abernethy and other famous doctors of the day, who would not receive fees, because she was the widow of a medical officer. I saw my mother in her coffin and never forgot her, grieving for months over her loss. After her death I became a boarder at Miss Payton’s and was very unhappy, so that when my guardian, Mr McKinloch, a great friend of my father and mother, came back to London from India, and saw me, he sent me to another school, at Clapham, kept by a Miss Montier, where I remained for two years. Two Grants were my school fellows, one the mother of the Rev. Mr Hutchinson of New Zealand, and the other became Mrs Thomason, wife of the Governor of Agra. Mrs Burn, the Bishop of Nelson’s mother, was also my school fellow, and Miss Kissling of Auckland. Lady Heneage died while I was at School at Clapham. She wished to leave me a legacy, but her sister would not allow it. I next went to school at Oxford House, kept by two old ladies, Miss Priscilla and Miss Susannah Brown. The elder always worn a turban, was very stately and dignified, and the whole school system was different from anything nowadays.

When out walking in the parks two by two, a governess at every fourth row, we were obliged to wear green veils and turn our eyes to the wall if any gentleman passed. Miss Priscilla always spoke of men as “odious creatures, necessary evils”, and advised her pupils not to marry. We had several masters who attended the Queen – Monsieur Riviere who took us for drawing, and a M Sacre and Mr Jenkins who taught dancing. There were about 60 pupils and we had a dear old French governess who could not speak English, so we just had to become proficient in the French language. Our manners, our walk, accent, how to eat and drink gracefully, how to sit down, how to converse – all these were strictly attended to along with many other graces – matters which nowadays seem to be totally neglected.

I used to spend my holidays at 47 Montague Square, the house of my guardian Mr McKinloch of the Mercantile House “Rickards, McKinloch and Co”, whose failure afterwards ruined many rich old Anglo-Indians. My guardian was supposed to have retired from India with a fortune of 30,000 pounds, and he certainly lived in great style. At his house I saw many of the great men of the day, and from the age of 15 to 17 I always attended his large dinner parties. As he was then a bachelor, he would invite some married lady and her daughters to stay during my holidays, so that I could be chaperoned. In 1827, I left school and went to Edinburgh where I had relatives. From there I went to Argyllshire where my father’s favourite brother, Captain Alexander Campbell, formerly of the East India Company Service, had purchased a lovely property called ‘Inniston’, not very far from Dunstaffnage. Here we were surrounded by family

Page 8

connections, the Campbells of Lochnell, of Barcaldine, Sir John Campbell of Airds, and many others among all of whom I visited. I became acquainted with Dr Norman McLeod’s family. His father was the minister at Morven, a wild Highland parish beside one of the numerous lochs of fiords. The sisters were all talented and wrote poetry. The old Highland hospitality and customs, especially the loyalty and devoted attachment of the cottagers or dependants [dependents] on the estate, to the laird of chief, were still in evidence there. On one occasion, when my cousin Sr Donald called out a neighbouring laird named Stewart, for some slight quarrel, they met in a glen in Appin, where Mr Stewart’s property lay. After they had exchanged shots, they shook hands and were turning away when they saw a number of their relatives perched on the brow of two neighbouring hills. Upon being asked why they had gathered there, the retainers replied that had either of their lairds fallen, his followers meant to shoot the survivor.

I had received several letters from my mother’s friends in the north of Scotland begging me to pay them a visit. Accordingly I went to my godmother, Mrs McKenzie, at Cromarty, who with the dear old Captain, her husband, completely spoilt me. From that time I always considered their home as my real home, and Mrs McKenzie’s nieces, the Miss Forsyths, were like my own sisters, especially one who afterwards became blind through an unfortunate accident. She was a most accomplished musician and sang beautifully I also stayed some months in the Hebrides, visiting many places, including Iona and Mull where two of my cousins were ministers.

My brothers all received cadetships from an old friend of my father, a Mr Ravenshaw at whose house, 9 Lower Berkeley Street, I frequently stayed while in London; and about the year 1834, my brother Archy, who had always been the most affectionate, wrote urging me to come to him in India, as he had a good appointment, and could afford to send me ample means for my passage. I did not meet with any suitable opportunity however, until 1835, when the Honourable Mrs Ramsay, whose acquaintance I had made in Edinburgh, resolved to take out her family to join her husband, at that time the General in command at Meerut and the Upper Provinces. Mr McKinloch, my guardian, was written to, and he invited me to stay in his house in Montague Square while all preparations for the voyage were being made. I forgot to mention that the pension from the Madras Orphans’ Fund, 70 pound a year, had been stopped in my case when I was 16 years old, because it was assumed that my brothers had made over their share of my father’s property to me on going out to India, and that being in possession of more than 1,000 pounds, I was not entitled to the pension. This sum however, I never received from my Uncle, my joint guardian, he giving me only what was needed for my passage money and outfit, which in those days was very expensive, and which I must say lasted me for many years after my marriage.

We all embarked for India on board the “Broxbournebury”, a magnificent Old East Indiaman, commanded by Captain Alfred Chapman, one of the most delightful men I ever knew, a perfect gentleman who treated Miss Ramsay and me like his own daughters. Among our fellow passengers were several whose names were afterwards famous in the annals of Indian warfare; they were then cadets and young civilians. At the time those younger sons who entered the Military and Civil Service were far superior in birth and position to those who now compose Indian society, especially those in the Artillery and Engineer Departments. Our voyage lasted six months. We were one month at Madras, where we took in a passenger to Calcutta, the afterwards famous Lord Macaulay. I used to listen to his arguments and conversation on religious subjects in the cuddy after lunch, with Captain Chapman, and fascinating this was. On reaching Calcutta, I parted from the Ramsays for a few weeks, and was received by the Hon. Mrs Udney, who lived in the Union Bank, of which her son was manager. Her daughter,

Page 9

Emily married a brother of Mrs Raikes whose family settled in Nelson While with Mrs Udney, I received numerous invitations to balls and parties, for the arrival of our party (the Ramsays) caused quite a stir in Calcutta society. I declined all these invitations, much to the annoyance of Mrs Udney who was anxious to introduce me into what she considered the best society. But I was not at the time interested in that sort of life; for I had been very much impressed by Captain Chapman’s religious opinions on worldly society, and I was besides, anxious about my youngest brother, who had been seriously ill, and whose whereabouts I had been unable so far to discover. His Regiment was the 43rd Battalion Infantry, but I did not know where it was stationed.

I spent many hours reading in the drawing room, an immense lofty room on the second floor, with many full length windows. A raised verandah outside, closed in with rattan, shut out the intense heat and glare. One day I was told that a gentleman wished to see me. Upon his entering the room I rose to greet him, whereupon he came forward, took my hand and said, “You do not know me, but I would know you as a Dunstaffnage anywhere. My name is McIntyre. My father and mother were cottagers on your father’s estate. My mother was foster-mother to your Uncle Alick, who brought me out to India. All I have I owe to him. I’m now a rich man. Can I serve you in any way?” I told him of my anxiety about my brother, and he promised to find him and let me know his whereabouts. A few days later he called again, and told me that Osbourne had been dangerously ill and sent up the River Ganges for a change. The doctor had ordered him a voyage to Europe, but he was so deeply in debt he could not leave the country. Mr McIntyre then added, “But I have seen his principal creditors, paid all his debts, booked a passage for him in the next ship that sails for England and given him money to meet all his expenses. I should be glad to do anything else I can for you”.

You can well imagine that I was overcome with gratitude and with many expressions of regard, we parted, I never saw him again. But numerous are the instances I could relate of the generous, warm hearted, noble conduct of old Anglo-Indians, giving assistance most liberally to brother officers in less fortunate circumstances and providing for their widows and orphans

In about six weeks or two months, Mrs Ramsay having hired a fleet of boats for our party, which consisted of herself, her two sons, aged 14 and 16, her daughter and me, together with about 30 servants, we started out on our long voyage by river for Meerut, at the rate of about 20 miles a day. There was one large budjerord, one smaller in which I was to sleep, a cooking boat and several boats for baggage and for accommodation for servants. When the wind was favourable we sailed up stream, but with a strong current against us, we generally had to be pulled along beside the bank by dandies or boatmen, who carried long ropes over their shoulders. At night we anchored or drew up as close to the bank as we could, a plank then being thrown across to enable us to get on shore. It was a picturesque sight, the innumerable small fires all around and the native servants, several of whom had their wives and families with them, squatting in groups, chatting, singing and smoking their hubble-bubbles (hookahs), or recounting the events of the day in Hindustani. This language I soon picked up, becoming very fond of Ayah, or lady’s maid, who taught me we were entertained at the different military stations through which we passed and this broke the tedium of the journey. On our reaching Cawnpore, an unfortunate accident occurred. My budjerord, while I was at dinner in Mrs Ramsay’s boat, struck on a sunken log and immediately began to fill. The other boats all stopped and the crews assisted my men to get my trunks and baggage on shore; they succeeded in saving everything. Fortunately arrangements had been made for me to proceed by dawk so it was not of so much consequence.

Page 10

I reached Meerut in about 43 hours, travelling night and day, and changing my 12 bearers every 12 miles. My dearest brother Archy rode out to meet us. We had been parted for 10 years. I found that the doctor attached to the 5th Cavalry was the son of a gentleman at Cromarty, and I had known his family the Davidsons, well. I was therefore soon quite at home with him and his wife. They were most kind people and their baby boy was a great pleasure to me. He is now Mr Edward Davidson of the ‘Spit’, near Collingwood, with a family of 10 sons and daughters. He married a Miss Mackey of ‘Drumduan’, Whakapuaka.

A fortnight after I had reached Meerut, the Ramsay party arrived, and my brother received a letter from his friend, Lieutenant Gascoyne, saying that he had asked for leave of absence for a month, and would be at Meerut almost as soon as his letter. As it was in the middle of the Parade, or cold season, he had to apply for leave “on urgent private affairs” as he put it. Otherwise he would never have got it, for he only wanted to get married, as he told me afterwards. We were married in February, 1835, before the end of the month, by special licence. I had only one bridesmaid, Anne Ramsay. Shortly afterwards, we left, and proceeded to Cawnpore, where my husband’s regiment, the 5th Cavalry, was stationed. The officers and their wives seemed to me like one family, with colonel and Mrs Kennedy as parents. The latter had two daughters married in the Regiment, Mrs Alexander and Mrs Blair. They, alas! Together with many more dear friends of ours, were murdered in the Mutiny of ’57.

While at Cawnpore, we were all invited to a party given for the military and civilians by the very same Nana Sahib who was the chief agent in the Cawnpore Massacre, and in the very same building we spent the evening, entertained by Nautch girls. A short time before 10 o’clock, I observed to my husband that the native servants were shutting all the doors and windows and becoming alarmed. I insisted on his taking me outside, where we found the flat roof of the building crowded with spectators, watching some magnificent fireworks which the natives were letting off. My husband laughed at my fears, for I had thought they were going to murder us, I felt sure they would do so sooner or later.

My health giving way, we went for a change to Calcutta, intending to go home if it did not improve. But I rapidly got better and shortly after our return to Cawnpore, my eldest child Isabella, was born. I must here mention that my dear brother had found himself so depressed and lonely after my marriage, that he applied for leave to visit Calcutta with a view to finding a wife, which he soon did. For seeing a young lady in the Cathedral on the first Sunday after his arrival, he made enquires as to her name, residence, and family, wrote to her father, an indigo planter up country, stating his name, position and so on and asked permission to pay his addresses. He always was of an impetuous, enthusiastic temperament, warm hearted and entirely unselfish. The young lady was exceedingly pretty, her age 16 – a Miss Emily Payter. Her mother was a native lady, who having separated from her husband, lived in her own house in Calcutta, where I afterwards visited her. Emily was an only child. She had been brought up and educated by some of her father’s friends in Calcutta. Archy and she spent some days with us at Cawnpore on their journey.

My brother was one of the very few to whom marriage made no difference to his love for his sister. While he lived he was the most devoted, loving relative I ever had. He was Adjutant to his Regiment, which doubled his pay, making it in those days about 1,000 pounds a year. They had four children. The eldest, a girl died young. Of the boys, Archibald Dunstaffnage Campbell and Charles Gascoyne Campbell, Archy entered the Indian Service and retired quite young as a Lieutenant-colonel, marrying the daughter of General Ironside, and residing at Princess Buildings, Hyde Park, London. Charles

Page 11

managed what was left of his mother’s property in India. After his father’s death, his mother had married a young Lieutenant named Wyndham, of Lord Egremont’s family. He spent most of her money and was killed by falling from a balloon into a lake in Bengal; after which unfortunate happening, his widow went to England to reside near her son.

My brother Archy, in 1843, had had an attack of a liver complaint and was ordered a sea voyage. Accordingly, with his family, he started for England in 1844. They put in at the Cape, Archy being still very ill, as was also a fellow passenger named Connolly, a civilian, Dr Bickerstaff, the chief medical man, attended them both, and told them it would be madness to think of continuing the voyage until they were better. My brother replied that he must do so, for he had paid the passage money for his wife and family to London, and could not afford to lose it. Mr Connelly, who was present, entreated him to remain, as he himself intended doing adding, “Here is a cheque, my dear friend, for 1000 rupees, and draw upon me for as much more as you need”. In one month they lay side by side, in the Capetown burying ground.

My sister-in-law, with her three infant children was left a stranger without friends or means, as she thought, but the Almighty Friend of the widow and the fatherless, was faithful to His promise – “Leave thy fatherless children and I will preserve them alive, and let thy widows trust in me.” I may here mention that my father, Captain John Campbell, on his death-bed in Cuddalore, had put his bible into the hands of his trusty bearer and told him to take it to the “Mem Sahib” upon her landing, being unable to write himself, and to put it into her own hands. The leaf was turned down at that verse underlined as his last words. I have the Bible still. A Colonel Rutherford, father of the Rev. Mr Rutherford who was formerly one of the Wairau clergymen at the Cape, hearing of the sad circumstances of Mrs Campbell wrote asking if she would prefer going on in the next ship to England, or returning to Calcutta. She preferred the latter course.

He then wrote enclosing money for all expenses, having already paid her passage and associated expenses to Calcutta, thereby ensuring every comfort for herself and her children. Such were our kind and generous officers in the old East India Company Service.

In 1837, we were ordered to Muttra from Cawnpore, where my eldest son, Charles Cecil McKenzie was born. He was a lovely child with flaxen curls and large blue eyes, and with skin like snow, but at the age of 16 months on July 2 he died, just wasting away in my arms. On the morning of the 23rd, my dear son, Frederick John William, names [ named] after the General’s son and Uncle John, was born. Eighteen months after, Mary Catherine Helen was born, on the 1st January 1840; and when she was nine months old, we resolved on visiting England.

We had been on the Himalaya Hills on sick leave for six months, at Mussourie. Our house was in a lovely valley or cud and was called ‘The Hermitage’. Another bungalow just above, was ‘The Monastery’, and there Mrs Masters, a sister of Mrs Blundell and her family lived. Your dear grandfather’s health did not seem to improve very quickly, so once again all our possessions were sold and we started in janpan for Dehra Dun, a very pretty English looking village at the foot of the hills, then continued by palanquin dawk for Ictarapore and the Ganges, and hence by boats to Calcutta. I cannot give you any idea of the magnificence of the scenery of the hills with the cedar forests, the lovely valleys, full of rhododendron, walnut, cherry and many other flowering trees, and capped by the everlasting Snowy Range, the highest mountains in the world. The air, the sky and the earth are all exquisitely beautiful, and the thunder storms in the rainy season grand and awe-inspiring beyond all description.

Page 12

Nothing eventful occurred on our voyage down the Ganges and we sailed for England in the ‘Carnatc’, commanded by Captain Voss. Captain Brine of her Majesty’s 19th Infantry, with part of the Regiment and the soldiers’ families were on board also. When we were about half way across the Atlantic, late in the evening, suddenly a cry of ‘Fire! Fire! was heard and smoke and flames were seen coming from the steward’s pantry which was full of wine, spirits, and other inflammable goods. The door was locked and some little time elapsed before it could forced open and the buckets ranged from the ship’s side and handed from one to another in a line, the women and children meantime shrieking with terror. It was an anxious time for everyone but the flames were soon brought under control and order was restored, by god’s mercy.

On our arrival in England, we went at once to Clifton where my husband’s family had resided for many years and were much esteemed, Mrs Gascoyne being well known for her charity and benevolence. She was an earnest Christian and a noble lady and I loved her dearly. Her daughters, Mary and Sophie did not resemble her in any way. Sophie had married her Mr Williams just before our marriage in 1835, and had at this time six children. They live in Frederick Place, a very short distance from Carlton Villa, your great-grandfather’s house.

My husband’s father was, or imagined himself to be a great invalid, and was the most considered by the whole family. Mrs Gascoyne attended to all his wants and fancies herself, always bringing him his breakfast in bed and his lunch in the drawing-room. Their income was about 600 pounds a year, but every luxury was provided for Captain Gascoyne. In short, he was a thoroughly selfish man, Mrs Gascoyne the very opposite. It is hoped that her qualities may predominate in her succeeding generations. The room that was occupied by my children was unfortunately over the drawing-room, and Captain Gascoyne soon complained that the noise of the little pattering feet annoyed him, so after much consultation with my husband, I resolved to send Fred and Mary to some dear kind cousins of mine in Argyllshire, the Rev. Dugald Campbell, who with his two sisters, Mrs Fraser and Miss Campbell, lived at the Manse some three miles from Dunstaffnage Castle. Here I knew my children would be more than welcome and thrive on Highland air and Highland fare, though I felt very much the hardship of being separated from my little ones. Isabelle, my eldest, was a very quiet, shy, reserved child and gave no trouble to anyone. She went to day school first and then a young lady teacher for two hours every day. We stayed at Clinton as far as I can remember for about 12 months, when my husband acceded to my request, (indeed in fulfilment of a promise made before our marriage) that we should visit my friends in Scotland.

On our way, we stayed for a week at Liverpool with the McAndrews, a family of rich merchants Mrs McAndrew was one of the Forsyths of Elgin, her Uncle the author of “Forsyth’s Italy”, and all of them were remarkably talented and charming. In Liverpool, my Husband was invited to dinner in the town hall, he being the nephew of the ‘old General, Isaac Gascoyne. A full length portrait of the General hung at one end of the room, recording what he had done for Liverpool during the 28 years he had represented it in the House of Commons. We took a furnished house in Elgin for a year and made various excursions in the neighbourhood, visiting many dear old friends at Nairn and Cromarty. My cousin, Mrs Fraser, also came to us for six months and here my daughter Emily Charlotte Annie Justina was born.

We left Elgin when Emily, or Amy as she was called, was about one month old, and again took up residence at Clifton. My husband, wishing to see his brother and family, who lived at Plymouth where John held the appointment of Secretary to the Royal Yacht Club, wrote enclosing a cheque for 70 pounds to pay the expenses of removing

Page 13

the family to Clifton; and they accordingly arrived, Uncle John, Aunt Julia and the 10 children, and took a house Carlton Villa. Aunt Julia was considered to be a very handsome woman, but I did not admire her style and her dress was not to my taste, flamboyant and unladylike, I thought. Uncle John had a remarkably handsome figure and a very aristocratic manner and walk (as had your grandfather also.) Shortly before we returned to India, we were disappointed of some remittances. We had expected 300 pounds and knowing that Uncle John had just cleared 1000 pounds by some business transaction my husband frankly asked him if he could return the 70 pounds he had sent him on a former occasion. His reply was characteristic of the man; “My deaf fellow, how readily would I do so were this money (the 1000 pounds) a real gain, but the fact is, I can hardly call it so, having lost so much in years gone by”. He should have said not ‘lost’ but ‘squandered’. So much for Uncle John’s character. He loved money more than all else.

Not long afterwards we set sail for India, my husband’s health quite restored and much against the advice of friends we resolved on taking all our children back with us, instead of following the general plan of leaving them at school in England. I took a Scottish servant out with me, intending to send my children under her care to the hills during the hot season and thus avoid any ill consequence of the hot climate of the plains. In September 1843, just one week before landing at Calcutta, another dear little girl was born. She lived only for five months and died at Mattra. She was more like an angel spirit than an ordinary infant, never crying or showing temper and many people told me afterwards she did not look as if belonging to this world. She was so lovely and intelligent, I grieved terribly at her loss; but in later years I felt thankful she was taken from the evils to come, to be with her little brother Charles in heaven, where I shall receive them again.

On rejoining the Regiment at Kurnaul, we found it had been almost annihilated in the Cabul campaign. A large force consisting of Cavalry, Artillery and Infantry, had been sent to quell the disturbances at the time of Shah Shuja’s accession to the throne and we had taken possession of the country and citadel. After some months, Shah Jehan (I think that was his name) brought a large army and besieged the citadel and our troops were nearly starved. It was in the depths of winter and General Elphinstone a very old and infirm officer, had resolved to give up the citadel on the promise of safe convoy. But the enemy broke faith and the moment the gates were opened, the ladies were all taken prisoner and the troops harassed on every side, were refused supplies. Thousands fell in the Passes, blocked up with ice and snow, only one officer, a Dr Byron of the Calvalry, escaped to Jellahabad. The rest all perished. Lady Sale with about a dozen other ladies, was kept prisoner for some weeks, but they were finally rescued. She was a remarkable woman and on one occasion proposed that they should stand around a barrel of gunpowder, to which she would apply the match and thus end matters. She was afraid the Sikhs might torture or insult them. Fortunately her proposal was not accepted.

We were ordered to Muttra, then to Kernaul. The Governor-General, Sir Henry Hardinge, resolved on making a tour of inspection in the Upper Provinces and my husband was ordered to attend him with his troop of cavalry. As we had never once been separated since our marriage, I of course made preparations to accompany him, sending all my children except the baby Charles, to the Hills, under the charge of a Scottish servant whom I had brought out with me. We had a pleasant march.

Page 14

The camp was a large one, consisting of the Governor-General, Staff, with elephants, camels and a large number of tents and camp followers. Sometimes I travelled in my Palanquin, but more often I sent the baby and the ayah in that and Dr Spencer the doctor of the Regiment, who was with us, drove me in his buggy. My husband rode on his charger at the head of the troop. When we were within one march of Ferogepore and about a mile from camp, a young officer came galloping towards us shouting out, “Have you heard the news? Thirty thousand Sikhs have crossed the Sutlej; an engagement is expected and every lady is ordered out of camp today before noon”.

I felt paralysed. On reaching our tent, I saw an elephant with a howdah and trappings which my husband told me Sir Henry had sent to take me to Kurnaul. The other four ladies each had an elephant also.

It was a sad cavalcade. About half way back we met an officer on horseback with dispatches, and as he had ridden in haste to reach the camp as soon as possible, he requested us ladies to give up one of our elephants to him, his horse being spent, and two of us to ride together. I gave up mine. That night he reached camp just as the Battle of Moodkee was fought, and was killed. I had only thought to do him a favour, poor fellow.

Three of the ladies who accompanied me on that march back to Kurnaul were made widows, their husbands dying on the field of Moodkee One was the Honourable Mrs Somerset; whose husband was aide-de-camp to the Governor-General. Very many brave soldiers, my husband told me later, mounted their charges joking and saying what capital fun to have a brush with the Sikhs, little realizing the strength and trained skill of the enemy, who had French officers among their leaders, and who fought with determination. Many of these brave fellows were left dead or wounded on the field all night. The attack was so unexpected and no necessary precautions had been taken or defences made.

My husband had been ordered on escort only, and was stationed about three miles from camp, with orders to keep a good look out for the enemy; and just as he had taken off his sword and was preparing to make himself comfortable for a hours rest, his subahdar had galloped up, saying that there was a cloud of dust at some distance, which could indicate a body of cavalry. My husband immediately saw through his telescope, which he carried always slung over his shoulder, what it was and giving orders to his men, galloped back to camp and gave the alarm. In a short time, almost before they had time to form the Regiment into line of battle, the Sikhs had opened fire and the Battle of Moodkee was fought and won by the British, but with terrible losses on our side. That same night, my husband and several other officers found themselves at about 10 or 11 o’clock, at the edge of a clump of trees. They had got separated from their Regiments, having only a few of their men with them after following the retreating enemy. It was bitterly cold – the 19th December, if I remember rightly and Major Gough, a nephew of the Commander-in-Chief, proposed that they should try and find their way back to camp; but all professed utter ignorance as to where they were and in what direction the camp lay. When my husband offered to lead them, feeling sure he could do so, they hesitated, but at last made up their minds to follow him. And he piloted them safely to the mess tents of the Cavalry, where they were welcomed as from the dead, having been reckoned among the missing ones. All hope had been given up of their being alive.

My husband used to say he had a sort of sixth sense of locality, always being able to retrace his steps and find his way where others were at a loss. I received letters daily from my husband until the Sikhs cut off communication by Dacok, but he kept a daily journal and forwarded it to me from time to time. It was a dreadful time of anxiety for the

Page 15

wives and families left behind at Kurnaul, and many an affecting incident occurred. Some rumour would reach us that such and such an officer was wounded or killed and I remember sitting up with one poor lady whose husband, Colonel Mair, was among the list of those killed, but who afterwards recovered from his wounds.

She, poor thing, was in violent hysterics all night and quite delirious. We could by putting our heads close to the ground, hear the thud, thud, of the artillery guns and the reverberation along the foot of the hills, although we were 60 miles away.

One night we had a terrible fright. A native rode into the station saying he had passed 400 Sikhs on their way to burn and destroy the cantonment of Kurnaul. What could we do? The soldiers’ wives and others in the area were all ordered into a sort of barricaded place. Most of the ladies who had carriages got them in readiness to start in the dark for Saharanpore, a small station near the Hills. I got the children out of bed, dressed them in warm labodes, tied a bag of rupees and other valuable round my waist, put the children into the palque gharri, a small kind of omnibus, and extinguished all lights while waiting for further tidings. However it proved a false alarm. The 400 Sikhs, more or less, turned out to be some religious devotees about to bury a great chief at some holy spot beyond Kurnaul The next day however, several ladies resolved to move to Saharanpore, as a safer place and Lady Gilbert, whose husband, General Sir Walter Raleigh Gilbert was in command with the army, kindly offered to take my two elder children in her carriage. The rest went in palanquin. We reached Saharanpore in safety and were lent government tents while we remained.

In the meantime two more severe battles were fought. That of Ferozeshah was very nearly a defeat, but owing to the ‘merciful’ deliverance by ‘Almighty god’ to use the words of the Governor-General, we gained the day. For twenty-four hours the Sikhs artillery guns had played upon our troops and at last our guns were silenced. Our ammunition had come to an end. Sir Henry called a council of war and said, “Gentlemen the day is lost, I die here. Order the Cavalry and the infantry to defile into the fort, protected by the Artillery as long as possible”. He then turned to some German prince who had been in camp and requested him to take charge of his dispatches etc…and leave at once for Calcutta, ordering him a strong guard. At this juncture, the Sikhs guns having ceased the fire suddenly, they were seen to be abandoned and the men rushing pell-mell towards the bridge of boats by which they had crossed the Sutlej. They were panic stricken, imagining when they saw the Cavalry and Infantry leaving their positions, that they were going to cut off their retreat to the river and get in the rear. On seeing this, Lord Gough, the Commander-in- Chief, called out in his strong Irish accent, “Try them with the cold stale, my boys!’ and the Infantry pursuing them with their bayonets, drove thousands of them into the river. My husband said it reminded him of the defeat of the Assyrians in the Scripture. Before leaving the field, Sir Henry called his generals together once more to return thanks to God for their signal deliverance and victory.

The Battles of Aliwai and Sobraon, in both of which your grandfather was also engaged, took place shortly after, Ferozeshah, and ended the Sikh campaign. Owing to Colonel Alexanders being wounded, your Grandfather commanded the 5th Cavalry at Sobraon. He wrote to me, “I have seen war and am horrified, and hope that no son of mine may follow his father’s profession”. He was, I was told, the coolest and bravest officer in the Regiment. He said he did not know what fear meant; and a brother officer told me that when the bullets were falling like a shower around them, at night where they stood unmounted beside their horses waiting for the order to charge, my husband was as calm and spoke as quietly, as if he had been in his tent. The officer had remarked in this to my husband, who replied that he felt perfectly calm and added jokingly, “But there,

Page 16

I do not present such a target for the bullets as you do”, he being tall and thin, Captain Wrench a very stout man.

Now I must tell you that your grandfather was no ordinary character. He was the most perfect gentleman in manner and appearance generally that I ever knew. As a boy he was his mother’s favourite, and it was a great grief to her that he chose the military profession. He was a scholarly linguist speaking French fluently, Hindu, Ordu, Arabic and Hindustani. He was appointed interpreter to the Regiment. He wrote many pretty pieces of poetry, and from his boyhood had a strongly poetic, chivalrous, imaginative, but unpractical turn of mind. He had peculiar views on most subjects and was inclined to melancholy and withdrawal from general society. The few friendships he formed were deep and lasting, and he was a sincere Christian. His voice, accent and manner had a strange, rather peculiar charm and his reading aloud of Shakespeare and indeed of all poetry, was greatly enjoyed by all who heard him. He was naturally graceful in every action, and courtesy itself to womanhood, whether young or old, rich or poor. It was almost impossible for his wife or his mother to help worshipping him.

But to my resumé my narrative. After the campaign was over, we went again to the hills and my husband, wishing for quiet and rest, chose Lugooghaut, a small military station in the confines of Nepal. But I forgot to mention in the proper place, our visit to Kussowlie, Subathoo, and Simiah, the last and most delightful place in India, The climate resembles that of Nelson in summer and of Dunedin in winter, the scenery lovely beyond all description, the hill are covered with the most luxuriant vegetation – rhododendrons, cherry, walnut, horse chestnut, deodar and other pines and flowering shrubs. The cuds and valleys are covered with wild hyacinths, and most of our English wild flowers, wild strawberries and raspberries and the cape gooseberry in profusion, and beyond all, the Snowy Range, which as I said before, is the highest mountain range in all the world and the same white cold clear horizon all the year round. At Simlah, however, the clouds are often seen below and all around you and the thunder storms are terrifically grand and full of menace. Two bungalows were struck by lightening while I was at the Hills and one lady and her Ayah killed on returning from Kussowlie.

We were ordered to Meerut, another delightful station, where we had a large and commodious bungalow and my husband made me a present of a charming landau and pair. We had many friends there, besides the ladies of the Regiment, to whom I was very attached. The native servants of India were generally most faithful, but the following incident, which occurred when we were in the tents at Saharanpore will show that our prestige had suffered even at this time and that the feeling which ended in the mutiny of ’57, had already begun to manifest itself.

When we wished to return to Kurnaul, I applied to Captain Simpson, the officer commanding the station, for a supply of native carts to transport my servants and baggage. He replied that he would do his best, but that the natives were in such a state of insubordination that he had little authority over them. He contrived to get one cart and my servants quickly began loading it with their goods and chattels. Suddenly an armed man rode up and drawing his sword, commanded them to unload instantly. I was standing at the tent door behind a screen or ‘chick’ of bamboo. I readily understood the native language and coming forward, said “Who are you who dare to order my servants? The cart was sent by the Sahib in command.” He made his sword fly round my head unpleasantly near and abused me in Hindustani. I very quickly stepped inside the tent, but my boy Fred, who was about seven years old, seized his Uncle Archy’s sword, which I always carried in my palanquin, and rushed at the man, until I pulled him inside. The man finally drove off in the cart in triumph.

Page 17

Your Aunt Charlotte was born at Meerut, in 1846, but my memory is faulty as to dates. My husband’s health had suffered severely from the Campaign and he resolved to retire from active service and sell his commission; for which he received 30,000 rupees. All my pretty furniture, carriage, horses etc.., were sold for less than a quarter of their value and we migrated to Luhooghaut, where your grandfather purchased a small estate with three bungalows on it. We occupied the best, and lent the other two to young officers who came up for the shooting season, there being an abundance of tigers, bears and other game in the hills round us, also numerous birds, which when stuffed, fetched a high price. Captain Lockett, who was our neighbour was a great sportsman. He and Dr Pierson, who was in medical charge of the district, were our only visitors.

In about 1850, during our stay at Luhooghaut, a very severe earthquake occurred, more severe than any that could be remembered since the English had possessed India. Your grandfather was reading one of Sir Walter Scott’s novels aloud to us in the evening, as was his custom, when about 7 o’clock, the slates on the roof began to rattle. They were large blocks about a yard square and heavy beams of cedar which supported them creaked and groaned most ominously. We all ran outside. The shaking lasted for 60 seconds or so, as far as I can remember. When the panic was over, the servants came rushing in, stating what various damages had been done. One was that the officers’ Mess House had been shaken down, which proved to be true and one unfortunate officer nearly lost his life. It happened thus. He had his right leg amputated some months previously, after it had been shattered by a blow from a tigers’ paw. Captain Auberb had wounded the tiger which, however, had pursued him, and there being no other means of escape, he had climbed a tree and clung to the branches. The tiger lay just below, tired at last. Exhausted, the officer tried to jump clear of the animal, but unfortunately did not succeed, falling just within reach of its front paw, which broke his leg. His attendant had come up, shot the tiger dead and conveyed his master home.

At the time of the earthquake, Captain Auberb was reclining on his charpoy, his wooden leg having been placed in a far corner of the room and his bearer gone on a message. When the officers all ran outside, he, unable to move without his leg, shouted to them, “Here! Someone give me my leg for mercy’s sake!” And he only escaped just in time before the wall of the bungalow fell.

On another occasion we had a snow storm all night and in the morning the ground all round us as far as we could see, was white, a very unaccustomed sight for my children. My husband and I were admiring the scene, when a native servant coming up, my husband said, “What is that huge log of wood doing on the pathway? Move it off”. When the man approached it, what a surprise to see it move with an undulating motion across a little gully and disappear, the native shouting “Samp! Sahab, Sampe hi!” It was a boa constrictor that had been partly paralysed by the cold, we saw small snakes, but not another boa constrictor.

While we were at Luhooghaut, my health, hitherto wonderfully good throughout my residence of twenty years in India, gave way completely, and after my daughter Caroline’s birth I was a helpless invalid for many months. We remained at Luhooghaut for about three and a half years. I was sent latterly to Almorah for a change and to be under the doctor’s care. During my absence, my husband received a copy of Hursthouse’s book, ‘New Zealand’, with which he was greatly impressed, but which I consider one of the most deceiving and mischievous books ever published on this colony. He resolved to take his family and settle in Nelson, where the Blundell family had gone. I was too ill to go with them and it was decided that I should proceed to England with one child, Charlie, and remain there with my mother-in-law, Mrs Gascoyne,

Page 18

until my health improved. Miss Sutherland would accompany the family and take charge of the children.

On our all leaving Luhooghaut and going down the Ganges, we were obliged to leave the Hoogley and go through the Sundarbans, by which the many branches of the River Ganges reach the sea and which wind like so many canals for miles and miles through the jungles around Calcutta. Arrangements were soon made for my journey to England via the Red Sea and Egypt and I went on board the “Hinrooctan”, one of the largest East Indiamen then built. There I said good-bye to my husband who returned on shore about 10 o’clock. It was a lovely moonlight night, everything being still and silent after all the previous bustle, except for the regular tread of the officer on watch on the deck overhead. Mine was the stern cabin and feeling very disconsolate and lonely, and not at all inclined to sleep, I climbed up on the bulkhead before the windows and looked about me. Just below, attached to the rudder chains, was a small boat or dinghy, containing two natives fast asleep. Suddenly the tramp overhead ceased and I heard a plunge, as of someone or something overboard about the middle of the vessel and presently a most extraordinary sound of gurgling or choking and splashing.

Straining my body forward, I caught sight of a white thing floating alongside and the same horrible noise was repeated. I then saw that it was a man wearing a heavy cloak and a white solar toupee I threw over some rope that was beside me and shouted with all my might to awake the men in the small boat. Happily I succeeded and one was overboard in an instant laying hold of and dragging the drowning European into the dingy, the natives paddled round to the side of the vessel and at once all the cabin door burst open. Every lady passenger, in a state of great alarm, appeared, believing it was her husband who, after having wished her good night and gone to enjoy a little extra conviviality with the officers, had stumbled overboard at last. “Oh dear! I’m sure it is my husband”, came from twenty cabin doors; and only upon learning that the individual was a bachelor, was peace restored. I may add that the gentleman was an officer in the Bengal Service, A Captain Bemply Baugh, who for the remainder of the voyage was like a son to me and saw me safe to Clifton, where I remained for sixteen months with Mrs Gascoyne, my mother-in-law. From there after visiting all my Scottish relatives, I too sailed for New Zealand in December 1853.

My husband had purchased eight hundred acres of land on the outskirts of the ‘bush’ at Motueka, on the other side of the Bay of Nelson. There I found a new world, in a very painful sense; and there we were buried alive for twenty years. Our capital was partly invested in sheep, the rest in land. We finally lost both, and all our savings in India vanished. I must add, however, that I can certainly say, “Goodness and mercy have followed me all my days from childhood to old age”, and now I’m ready to depart and join those loved ones gone before. God’s promises are sure even to the end. I have written this narrative straight off without a copy, and if there are errors please excuse them, as I’m now 78 years”.

Before I go on to relate what befell this family, here in New Zealand, I shall include an extract from the memoirs of little Isabelle, or Isa, as she was called, eldest daughter of Charles and Isabelle.

Page 19

CHAPTER II

CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

From the childhood memories of Isabelle Greenwood, eldest daughter of Charles and Isabelle Gascoyne.

The earliest thing I can clearly recollect is standing on the banks of the Hooghly River in India, holding my father’s hand and watching an English coming in. I had been born in Cawnpore, East India and was at this time four years old. The only white people I had seen besides my parents, were officers and their wives and children, so these strong ‘sailor men’ looked very interesting to me. I was a very timid child and would have been alarmed if I had not had hold of Papa’s hand. Very soon I was lifted into the boat and all our native servants were left behind. It was a great grief to me to part with Sudda, who had looked after me and used to carry me about and take me for walks; but everything was so new and strange that I soon forgot my sorrow in the excitement at what was taking place at the moment, and only knew that I must keep near my father. We boarded the great ship, an East Indiaman, amid what seemed to me much confusion. The loud shouts and orders to the men, the bustle and excitement, all combined to overwhelm and frighten me. The doctor had ordered that I should have a glass of Port wine every forenoon and when we had been some days at sea, my dear father gave it to me, thinking that I needed it; but my mother said that he was just spoiling me.

Next came the life in England at my grandmother’s home in Clifton. Grandfather, Captain Gascoyne, had been in the Royal Navy. Fred, Mary and I were put in charge of upper and under nurses, in two nurseries, a day and a night one, and confined there whenever we were indoors. It was so different from the freedom of our life in India and the large bungalow we were used to, with its deep verandah all round and the many servants all so willing to help and anxious to please. We were taken out for drives every day in England. I remember we all disliked the upper nurse who was sour and disagreeable and ugly, but Marianne, the younger one, was bright and pleasant and used to take us on the ‘downs’ and let us have donkey rides. When we returned to the house, we had to toil up the many steep stairs from the ‘hall’ to the nursery and I wondered why the English people had stairs. We had none in India. One day, just as we were brought in from a walk, I saw my father and his mother coming down arm in arm from the dining-room. I have a very vivid recollection of this, for I thought they looked most loving and beautiful, almost like angels. I cannot remember any time when I was not passionately fond of my father and did not admire him immensely. He was the handsomest of men. Grandmamma was beautiful too, her expression making her most lovable and father was like her. Mother and son were always devoted to each other. Grandmamma was French, her maiden name being De Coetlogan and she was very charming in her manner both in her own house and in society; and her goodness and kindness to those less fortunate than herself made her beloved by everyone. My childish ambition was to be like her.

We children did not care much for grandfather though he was never in the least unkind, but he struck us as tiresome as he complained of the noise our feet made running about overhead; for the nursery was over the drawing-room. He used to go out walking every day. One day I tried to help him on with his overcoat. I was only five years old and failed utterly, to my great mortification. It was also whispered among the servants- and we heard it from our nurse – that he was very fond of nice things to eat. We thought that it was greediness and were told by the nurse that it was downright wicked. So Fred and I felt doubtful as to his being a fine character. Grown-up people, we were

Page 20

told, always did what was right and proper. And it was the height of impertinence for children to do other than admire their elders. Aunt Mary Gascoyne, my father’s sister, was a foreign looking lady, who wore caps trimmed with pink ribbons. She was much older than my father. Another sister, Sophie Williams, lived somewhere near us and had several children, but we did not take to them as much as to our other cousins, the children of Uncle John Gascoyne, who had married a daughter of Admiral Cumberland, Julia Cumberland, and who also lived at Clifton. The eldest girl and I were sent to the same dancing school and were rivals in that art. We played together and were good friends.

During 1841 we all went up to live in Elgin, Scotland for a time, and there my sister Emily was born in the house of the Forsyths; my mother’s friends were almost all in Scotland. The Forsyth family consisted of father and two daughters who at that time must have been in their thirties. They had travelled on the Continent and were good, clever and well bred. The elder, Kate, was my godmother, the younger Isabella, was quite blind – the result of an accident in a carriage, when a parasol was opened for her by her fiancé who was sitting opposite her. There was a sudden jolt and the end of the parasol was driven into her eye. Complete blindness followed, the engagement was broken off and dear Aunt Isabella, as we called her, remained single until her death. She used to amuse herself by knitting in coloured wools and it was a mystery to me how she distinguished between the colours. When I asked her about it, she said each colour felt different to touch.

Just before we left Elgin to return to England, Amelia Sutherland came to us. She was tall, slender and good looking, with lovely auburn hair. A quiet, unselfish, tactful woman with plenty of good sense, she very soon had unbounded influence over all of us and was our friend, helper and teacher. She came to India with us and later to New Zealand and remained with us until her death in 1868. All the book- learning she had was gained at one of those good old Scottish schools where boys and girls were taught together. The boys frequently went to Edinburgh, passed stiff examinations, and became Ministers. Amelia’s taste in books was excellent and she and our father taught us all we ever learned.

I remember hardly anything of our return to Clifton except that Fred and Mary and I had our portraits painted by an artist named Fisher. They were beautifully done, as Fisher was a well-known artist and painted for the Royal family. Then came the news of a dreadful massacre at Kabul in India, which nearly broke my father’s heart. All the officers in his regiment except two were killed. It was the first great sorrow I remember. We all went then to London to prepare for our return to India. A great deal of shopping was done. We brought many books, both for grown-ups and for us children. We were taken to the zoo and various places of entertainment for children and also to pay visits to say goodbye to relatives and friends. One of these was to Misses Gascoyne, cousins of my father and I was impressed with the grandeur of the house with its purple velvet curtains lined with white satin, the powered [powdered?] footman and the Butler waiting upon us at the table. These cousins were the daughters of Colonel Isaac Gascoyne, my father’s uncle.

The voyage out to India was pleasant and very interesting to us all. We arrived at Calcutta and as my father was anxious to rejoin his regiment, which was then at Muttra, a boat was hired and up the Ganges we went partly by towing, sometimes even being rowed. It was a delightful way of travelling; every evening the boat was moored to the shore and we were allowed to go for walks – such walks; so full of interest and pleasure, with our father to point out and explain everything. He was an excellent linguist and could speak really easily to the natives, who always responded readily to his courteous remarks and inquiries and with a politeness equal to his own. Sometimes we would go to

Page 21