- Home

- Collections

- JUNE LI

- Harvest 04 - July 1958

Harvest 04 – July 1958

Harvest

VOL. 1 No. 4

PUBLISHED BY J. WATTIE CANNERIES LTD

HASTINGS & GISBORNE

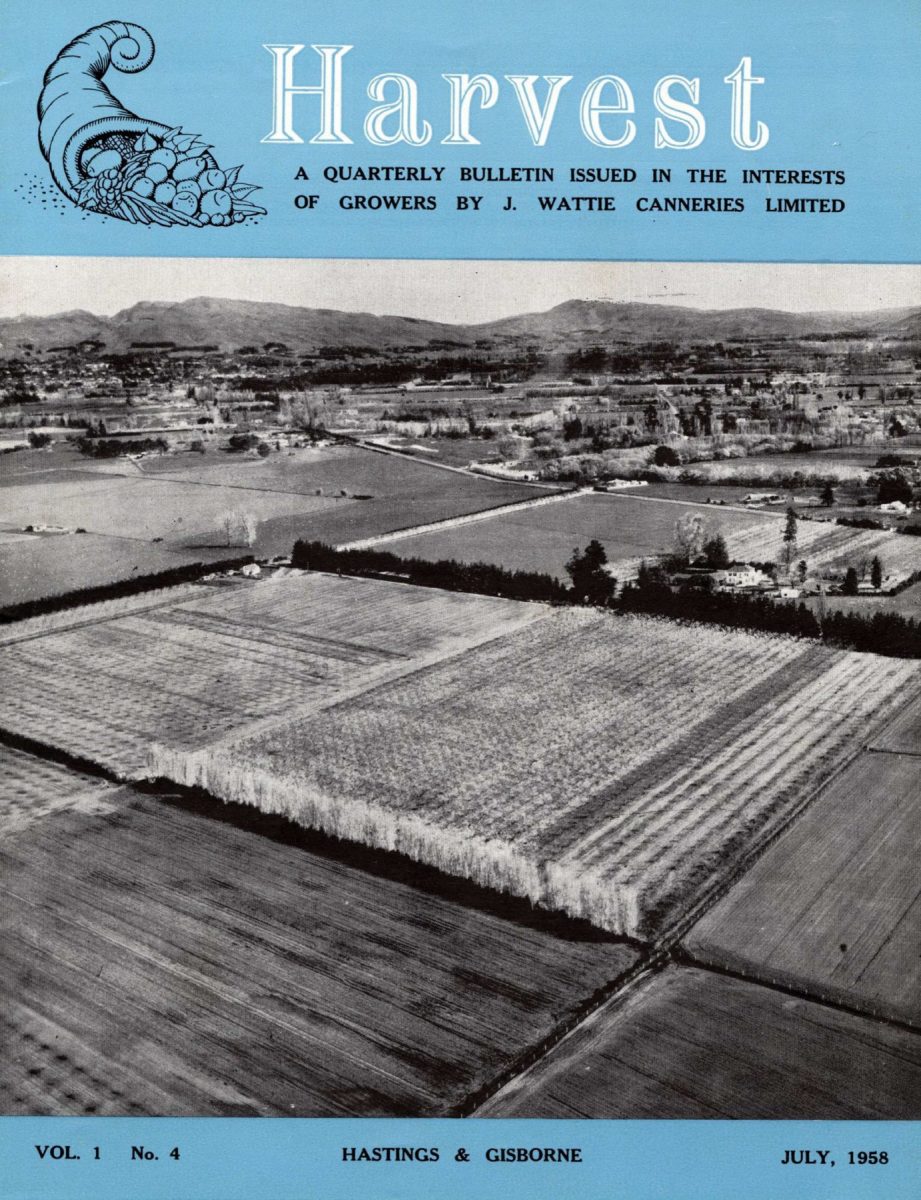

OUR COVER

The Company’s Farm at Mangateretere, Hawke’s Bay.

FOREWORD

WE ARE NEARING the end of our processing season once again, and it is very pleasing indeed to be able to say it has been a most satisfactory one – in fact, one of the most satisfactory in the history of the Company. It has made possible considerable extensions of markets. What is more, future prospects are bright. All this, of course, because of high production by you, our growers.

It could be said that there is no such thing as a “normal” season in our industry. A season that suits one type of production does not suit another, yet until late autumn, this season seemed an ideal one for most farmers.

Fruitgrowers have had record crops and excellent weather for disease control and harvesting. The average yield for peas was the highest on record, with returns of over £100 per acre for the first time. Beans, tomatoes, carrot namess and potatoes have been reasonable and, in spite of the dryness, corn crops were better than anticipated earlier in the season. Many of our growers, of course, raise sheep and cattle, and the dry autumn has not been so kind to them. With dry, windy weather, new grass was difficult to get away and the feed position has become serious.

So there it is: some growers have been very fortunate, some not so fortunate; but future prospects for the production of crops for processing are bright. It is rather early to say, but indications are for increases in many crops. The first crop of the season – broad beans – has been increased by 100 acres over last season, and dozens of growers turned away. In spite of increases it is regrettable that we cannot accommodate everyone, and waiting lists have already formed for many crops. However, it is a healthy sign for growers and J. Wattie Canneries alike. Together it means a great deal to the prosperity of the districts of Hastings and Gisborne.

Yours sincerely,

Bob June

Hastings Field Supervisor

ARE YOU THINKING OF ASPARAGUS?

The production of asparagus, especially in Hawke’s Bay, is developing rapidly. There are many reasons for this, the main one being an economic one. Returns from this crop can perhaps be improved upon by crops such as peaches, but not when over-head costs are taken into consideration. The outlay for equipment is very low, and the actual time of operation covers only about half the year. Hawke’s Bay soil and climate would appear to be the best in New Zealand for this crop, as other parts do not produce asparagus to any extent.

Demands for processed asparagus seem more or less unlimited. So far, local market demands have never been fully satisfied and the large demand from overseas has hardly been touched. J. Wattie Canneries will be planting a further area this year, bringing their own area up to 230 acres. With other growers, the area supplying our factory exceeds 600 acres, most of which is in bearing. A further large area is being planted this coming year, so that at last it is felt the local market may soon be provided for. In spite of the thousands of New Zealanders who grow their own, the demand for canned asparagus particularly is still mounting. Many say they prefer the flavour and texture of our canned product to freshly cooked asparagus.

Any grower contemplating the establishment of an area of asparagus should contact our field staff immediately. Plants at this stage can still be made available, but with the increased interest in this crop, it is doubtful if sufficient plants have been grown. Growers will be supplied with the scale of costs and practical advice on request, but a brief outline for general information in this article may be of interest.

COST OF ESTABLISHMENT.

Plants are the main item, and cost between £6 and £7 a thousand. Four thousand is the minimum number required per acre. This is for planting seven feet between rows and eighteen inches between plants in the row. Land preparation varies considerably according to whether or not drainage and levelling are required. Then there is the ploughing out of the trenches, placing and covering of the plants. The cost of maintaining the bed during the first year has been reduced considerably with the advent of pre-emergence weed sprays. First year costs have been found to run close to £40 per acre. This can be offset by the production of a crop such as green beans between rows the first year.

Maintenance during the second year is low, requiring only cultivation to keep weeds under control. In the third year the crop should more than provide for maintenance costs, and from the fourth year on for many years a minimum gross return would be £150 per acre. Well over half of this amount would be the net return.

PLANTS AND THEIR CARE.

Where seed was planted last Spring, the resultant plants are now ready for digging. Once the fern stops growing there will be no further root development. These roots or crowns can then be dug and stored, but if possible, it is advisable to dig plants as they are required for planting. The less storage, the better the results will be.

If it is necessary to store plants, the best method is to place them in boxes in a. dry condition with all soil removed, and stack them in a cool store. Stack with due regard to air circulation at a temperature of 32 to 33 degrees F. Failing this, remove all soil and dry in the sun. Stack in shade and keep them raised off the ground and covered. They will keep for many weeks in this way, provided they do not come into contact with wet soil or rain. The cover should allow air circulation. Plants that become damp will develop mould, which does more damage than the certain amount of drying out that may take place in storage.

One-year crowns are recommended. A well-grown two-year plant is too large to handle easily, and its cost is prohibitive. Two-year crowns can be used for any replacements that may be required. A few one-year crowns can be heeled in at planting time for this purpose.

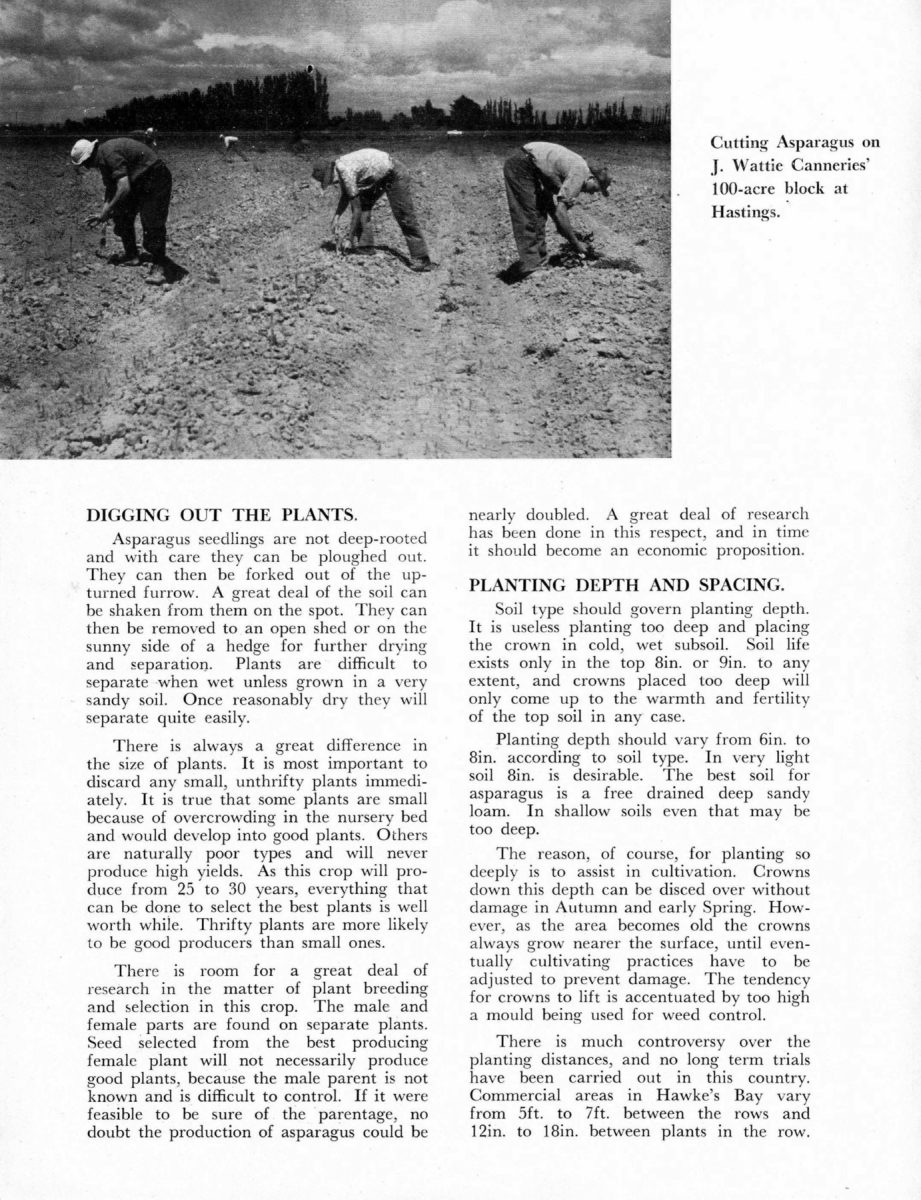

Cutting asparagus on J. Wattie Canneries’ 100-acre block at Hastings.

DIGGING OUT THE PLANTS.

Asparagus seedlings are not deep-rooted and with care they can be ploughed out. They can then be forked out of the upturned furrow. A great deal of the soil can be shaken from them on the spot. They can then be removed to an open shed or on the sunny side of a hedge for further drying and separation. Plants are difficult to separate when wet unless grown in a very sandy soil. Once reasonably dry they will separate quite easily.

There is always a great difference in the size of plants. It is most important to discard any small, unthrifty plants immediately. It is true that some plants are small because of overcrowding in the nursery bed and would develop into good plants. Others are naturally poor types and will never produce high yields. As this crop will produce from 25 to 30 years, everything that can be done to select the best plants is well worth while. Thrifty plants are more likely to be good producers than small ones.

There is room for a great deal of research in the matter of plant breeding and selection in this crop. The male and female parts are found on separate plants. Seed selected from the best producing female plant will not necessarily produce good plants, because the male parent is not known and is difficult to control. If it were feasible to be sure of the parentage, no doubt the production of asparagus could be nearly doubled. A great deal of research has been done in this respect, and in time it should become an economic proposition.

PLANTING DEPTH AND SPACING.

Soil type should govern planting depth. It is useless planting too deep and placing the crown in cold, wet subsoil. Soil life exists only in the top 8in. or 9in. to any extent, and crowns placed too deep will only come up to the warmth and fertility of the top soil in any case.

Planting depth should vary from 6in. to 8in. according to soil type. In very light soil 8in. is desirable. The best soil for asparagus is a free drained deep sandy loam. In shallow soils even that may be too deep.

The reason, of course, for planting so deeply is to assist in cultivation. Crowns down this depth can be disced over without damage in Autumn and early Spring. However, as the area becomes old the crowns always grow nearer the surface, until eventually cultivating practices have to be adjusted to prevent damage. The tendency for crowns to lift is accentuated by too high a mould being used for weed control.

There is much controversy over the planting distances, and no long term trials have been carried out in this country. Commercial areas in Hawke’s Bay vary from 5ft. to 7ft. between the rows and 12in. to 18in. between plants in the row.

J. Wattie Canneries Ltd. and Asparagus Ltd. have planted 7ft. apart, and this is recommended for various reasons. Firstly. tractors and planting distances are closely associated. It is an advantage to be able to drive in the row between the fern at times, although during the cutting season it is possible to work by straddling the row. Secondly, under present methods of weed control, earth is thrown over the bed during the cutting season to smother weed seedlings. If the rows are too close together, this is difficult and tends to make the mounds high because the soil is obtained from a narrow strip between the plants. Thirdly, anyone who has dug up or seen the root development on an established asparagus crown will realise they are very vigorous in root development and require room to develop over their long productive life.

Distance between plants in the row is also debatable. Here again, observation on established plants will show that the crown will develop up to 18in. across quite readily. Crowns planted that distance apart will form a solid row in time. If planted closer, there will be a heavier cutting in the first two or three years, but once the crowns meet they can then develop sideways only. Here again the long term view should be taken. We therefore recommend 7ft. by 18in. in general.

PREPARATION OF LAND.

This should be considered well in advance of planting time. Drainage may need attention, as it should be adequate. Tile drains become blocked with asparagus roots which interfere with their efficiency. The land should also be level.

Trials of new methods of harvesting are being carried out. If they are successful, one of the main factors will be level land. This can only be done before planting. Certain weeds, such as Californian thistle couch and convolvulus must be eradicated before planting. It is also advisable to grow a cultivated crop for the year prior to planting or make certain the turf is completely broken down before winter rains set in. This also reduces the ravages of slugs the first season, which can be serious.

Once the surface soil is well worked and level, it should be compacted by rolling, if this has not already been done by rain. Very deep ploughing is then recommended up to a dep namesth of at least 10in. to 12in. This carries good top soil down to the root area of the new plant, and leaves deep soil more or less free of weeds on top. This is then worked up sufficiently so that it will flow when the trench for planting out is made. Again, it should be compacted before the trench for planting is made, other- wise a false depth may occur. Trenches are easily made by ploughing both ways with a single-furrow swamp plough. If the soil is not too wet and is free from lumps, planting is an easy matter.

Free running soil is not easy to obtain during the normal planting time of June, July or August, and it often pays to plant as early as possible in June, when reasonable conditions often prevail.

Trenches should only be ploughed out from day to day. If they are made in advance, heavy rain or rain and wind may form a crust and loose soil is then not easily available for covering plants.

PLANTING.

Once the trench is made, planting should proceed immediately. The method recommended is the use of fruit picking aprons to carry the plants. The planter spaces the plants, dropping them at the correct intervals and with the crown uppermost. Another man follows up pulling the loose soil down from the side of the trench and covering the crown with 3m. to 4m. of soil. In this way each individual plant receives attention. Covering with an implement, such as a disc, can also be done, and may be successful where very free working soil is available. It is still necessary to walk along the row and make certain coverage is complete.

When planting is completed, the trench should be smoothed in readiness for an early Spring application of pre-emergence weed spray. This can be done by pulling loops of heavy chain on a fine chain harrow along the row. This breaks up lumps and makes an even coverage of spray possible.

At one time, the control of weeds in the first year was difficult and costly. Many areas have been abandoned because weeds took charge. Much hand work was also needed. The method was to fill the trench, gradually smothering the weeds as they germinated. If the soil was free flowing at all times, this is possible, but invariably a crust was formed and lumps, which rolled down into the trench, only made subsequent control more difficult. Hand weeding and hoeing then became necessary.

With the introduction of C.M.U. pre-emergence weed spray, first year costs have not only been reduced considerably, but control is much more efficient. The whole area can be sprayed with 3lbs. to 4lbs of C.M.U. to the acre, or just a strip along the trench itself. If the trench only is sprayed the land between trenches can be cultivated to keep it clean, and if required, can be utilised to produce a crop.

OFFSETTING COSTS.

As establishing costs for asparagus are high, ways and means of offsetting this cost are important. Much can be done by the production of crops between the rows the first year. This is not possible in subsequent years because of the fern growth. The types of crops, however, are limited. Early maturing crops, such as lettuce or French beans, are best. Root crops are not recommended, although carrots and beet can be grown.

Tomatoes have also been grown, but tend to interfere with the filling in of the trenches, and too much traffic in the harvesting operations tends to cause excessive packing of the soil.

Green beans are recommended, as they can be accepted by the factory for freezing or canning. Markets are sometimes difficult for other crops. When asparagus is grown for J. Wattie Canneries Ltd., an effort will be made to make bean contracts available. The beans are planted in November and harvested in January. When picking is completed, the whole area can be disced to remove the bean crop and to fill in the trenches, which should be done at this time of the year. The returns from a bean crop should completely offset the establishing costs of the asparagus. If any gaps appear they should be filled in with two-year crowns prior to filling in the trench in the late Summer or Autumn. This is not possible at any other time, as gaps will not show again until late the following Spring.

SECOND YEAR CARE.

In late August or early September of the second year, the whole area should be disced and harrowed to a reasonably fine tilth and kept worked until late September. It is then left until spears are up to indicate the rows. From then on clean cultivation between the rows is all that is usually necessary. If weeds show in the row, a light mould can be thrown up to smother them, but care should be taken not to build the mould up any more than can be helped. A small mould is a help to prevent wind breaking off the fern. When the fern yellows off, the whole area can again be disced and left until early Spring of the third year, when the preparation is again similar to the first cutting season. names

SEED FOR NEXT SEASON.

A considerable reduction in establishing costs can be made if growers produce their own plants. With the use of C.M.U. weed sprays the production of asparagus plants is a far easier and less costly proposition than it used to be. Particulars of seed varieties and further cultural notes will be given in the next issue of Harvest in plenty of time for next Spring’ s sowing, but intending growers should make enquires about obtaining seed immediately.

namesModifying second-year Asparagus to prevent wind damage and to smother weeds.

PEACH AND PEAR GROWING IN CALIFORNIA

A comparison with local conditions

For the past two fruit seasons, three American engineers from the Food Machinery Corporation of America have been employed in J. Wattie Canneries factory, Hastings. These men are experts on the machines used for peeling and coring pears and pitting peaches. The volume of fruit now handled warrants the employment of these men. It ensures the maximum efficiency of the machines, enabling more fruit to be handled in a given time and the reduction of waste to a minimum.

Some very interesting information is gleaned from these men, and our peach and pear growers may like to compare their lot with the factory suppliers of California.

ALWAYS A SURPLUS.

Unless very unfavourable conditions prevail, a surplus over and above factory requirements is always grown. This assures ample supplies to factories, and all growers are therefore treated alike.

By the time the thinning season arrives, the canneries have completed their surveys and know their requirements for the year. From then on the whole operation is controlled by Government inspectors; the namescanner and the grower have no direct contact. In most seasons a percentage of the crop has to be stripped completely from the trees. An inspector will tell the grower to strip say one row in every two, three or four, as the case may be. He will later inspect the orchard to see that the job has been done. The grower is compensated for the stripping operation only.

Price is not necessarily the same from year to year, but is arranged according to supply and demand. Price ranges from approximately £23 to £30 per ton for peaches. Pears are likewise controlled, and bring from £24 to £32 per ton delivered at the factory. These prices would be for all first class fruit. All peach varieties are clingstone.

A PERCENTAGE REJECTED.

A government inspector examines the crop after it is picked but still in the orchard. He informs the grower of the percentage of culls or rejects, and the canner will return this amount whether the inspector’s judgement is correct or not. These rejections are made for small or green fruit, over-maturity or rot. Each line, therefore, has to be kept separate by the canner. There would be no small growers with just a few trees, as we have in Hawke’s Bay, so the problem of keeping lines separate is not so great. All peaches are cool stored on delivery, and taken out as required. If too many peaches come forward at one time they are simply not accepted.

COMPENSATION. names

The grower does not know in advance how much of his crop he will have to strip, and therefore has to carry on as usual and prune, cultivate and spray his whole orchard. Only the cost of labour expended on stripping is paid for by the government; all the other work is carried by the grower. This is closely watched by inspectors. When a percentage of the fruit is rejected after picking, here again only bare picking costs are subject to compensation.

LABOUR TROUBLES TOO.

Labour is also a problem in California. The greater part of the labour forc namese is migratory, working north from Mexico as the season progresses, from one district to another. This unskilled labour is often the cause of much of the rejection after picking.

COMPARING OUR CONDITIONS.

Growers in New Zealand will appreciate from this brief summary that their conditions are not so bad. Most will agree that the method employed here cannot be controlled similarly because of the large number of small growers compared to fewer large growers. Although we reserve the right to reject a line on receipt at the weighbridge, once the line passes that point the grower is paid for the complete line according to grade, and our prices are higher.

LOCAL PEACH GRADING.

With so many small lines of peaches, grading for size is a problem, but experience over the years has shown that our estimates of size are very close and we have had practically no complaints. Lines considered difficult to estimate are checked over a sizing grader, so growers can rest assured that every effort is made to arrive at an accurate estimate of the three size groups, which in turn means the three prices paid to the grower. Many enquiries are received about the size and price paid for peaches. Our prices have remained constant for several years as follows: –

2½in. in diameter and larger 3½d. lb.

2¼ to 2½in. diameter and larger 2½d. lb.

Under 2¼in. diameter and larger 1½d. lb.

Since 1954 a bonus of ½/d. per lb. has been paid on the 2½in. and larger, bringing the price to 4d. per lb. This was brought in to try to encourage growers to spend more on thinning so as to get as much fruit as possible into the larger size. This fruit pays the grower better and of course, speeds up handling in the factory. The price for pears of sizes 2½in. and larger has remained at 4d. per lb. for the last three seasons. These prices compare favourably with market prices and are well above Californian prices. It would seem that cost of production locally is high, and this is mainly because of small quantities grown on mixed orchards. The larger the area the lower the costs of production. This is the main difference between local and Californ namesian production.

THIS VEGETABLE LEVY

Read all about it!

Many of our growers will have noticed a deduction on their accounts for a “vegetable levy.” Quite a lot of publicity has been given to this over the past year, but there are some growers supporting the levy who still do not know what it is all about. It means that you are supporting the New Zealand Vegetable & Produce Growers’ Federation, and your support is a worthwhile undertaking.

HISTORY.

The history of the vegetable growing industry over the past thirty years is very interesting. It is unfortunate that space does not permit a fuller account. The struggle to gain recognition and sup- port has been long and arduous. Many men have given up much of their time and energy, to say nothing of personal cost, to bring the industry to its present stage.

In the late twenties, far-sighted men, fighting for their own section of vegetable growing in their own districts, often travelled at their own expense endeavouring to set up an organisation to improve the industry in general. The depression years then set in and progress was slow. An attempt to have all vegetable growers registered was made in 1929. Another attempt was made in 1931, but the leaders of the industry had a difficult task, since growers had not realised the protective possibilities of a united Dominion-wide setup, and the Government was wary about matters such as compulsory registration.

In 1939 the council responsible for most of the spade work changed its name from “The Dominion Council of Tomato, Stone Fruit and Produce Growers Ltd.” to “The Dominion of Commercial Growers Ltd.” This held until the latest developments of 1957 made another change necessary and the body is now known as “The New Zealand Vegetable and Produce Growers’ Federation.”

During the Second World War, many changes were brought about. The war did a great deal to make the Government recognise the value of the industry. The Department of Agriculture became actively involved producing vegetables for the armed forces. An attempt to obtain reliable statistics on areas and production of various crops brought about the drawing up of “The Commercial Gardeners’ Registration Act, 1940.” This Act was delayed for various reasons until it was finally passed in 1943.

It can be claimed to be one of the few Acts passed with the unanimous support of both political parties. This did a great deal to put the industry on an organised basis, but did not overcome the problem of obtaining sufficient sustained finance to do very much. The New Zealand Commercial Growers’ Journal was established at the same time, and has done a great deal towards the unity of the industry. ‘

The Registration Act provided for the compulsory registration of all growers with half an acre or more, producing food for human consumption, with the exception of a few crops including potatoes, onions, swedes and one or two others. The Agricultural Department was responsible for the collection of the fees and the expense of the collection used up a great deal of the fee itself. It was obvious the industry could not expand under this system.

THE LEVY SYSTEM.

In May, 1955, the Dominion Council was informed that the Government intended to have new legislation drafted. This new legislation was partly brought about by growers of crops such as peas and sweet corn. These growers did not want any part of the setup as it was, and were told an effort would be made to have them exempted. These process growers later changed their mind, and have decided that by pulling in with market gardeners as such, all would benefit. As the expansion of canned and frozen foods has taken place, more and more vegetables are required for processing and less are used as fresh unprocessed food.

Another factor, the main one, which forced the issue of a levy system, was that the Department of Agriculture could no longer collect the registration fee after September 30th, 1957. If the Dominion Council tried to carry out the collection, it would entail more expense than the fee itself. Mr. Holyoake, Minister of Agriculture at the time, told the council that they would have to get out and do something for themselves, as they were the least organised major industry in the country. The turnover for the industry has been estimated at between £7 and £10 million, so it is indeed a major one.

Once again a tremendous amount of work was done by district committees and individual growers with their industry at heart. It was decided that no other method of putting the industry’s finances on a sound footing could be devised apart from a levy system. This levy has been fixed for the current year at one quarter of l per cent. of the net proceeds of the sale of vegetables at wholesale points, whether markets or processing firms. The fee is deducted at these points.

A START HAS BEEN MADE.

The Vegetable Levy Act, 1957, is now in force. The introduction of the system should prove a great benefit to the industry as a whole. The pip-fruit growers went through many trying years of development, and out of it evolved the present New Zealand Apple and Pear Marketing Board. This organisation has placed our fruit industry second to none in the world. Many countries are looking to our fruitgrowers for a lead. It is to be hoped that something similar can be brought about in the vegetable industry in spite of its added difficulties.

BENEFITS.

The amount of one quarter of 1 per cent., or 5/- in every £100, is a small amount, but with the Dominion-wide support great things can be done. The scheme is simplicity itself as far as growers are concerned. The amount is deducted from their returns. They then become full members of the Federation on application, with no further fee, and they receive a copy of the New Zealand Commercial Journal to keep them in touch with the developments of their industry.

It is hoped that as funds become available a great deal will be done in the matter of organisation and research. With good leadership, untold benefits could be derived from this major industry. It now involves the production of processed food for local consumption and export as well as fresh food production. With all growers now supporting a unified scheme, it should go from strength to strength for the benefit of all.

POLE BEANS 1957 – 1958

The 1957-58 season was not a favourable one for the growing of pole beans. Late plantings due to the long cold Spring, and the consequent late plantings of our pea crops, caused most pole beans to have a shorter harvesting season than normal. Unfortunately, in such seasons as this, late plantings cannot be avoided, as during the pea harvesting season the factory is concentrated upon the processing of peas, and cannot accommodate any great quantity of beans harve namessted during this peak period.

Climatic conditions prevailing shortly after the beans were planted also caused a setback in most gardens. The strong dry westerly winds caused uneven germination where the seed was not planted deep enough; not to mention the headaches most growers experienced when the wind made “birds’ nests” of their freshly strung rows!

The dry summer months which followed did not seriously affect many crops, as most growers have now installed irrigation of some kind.

The importance of adequate shelter was made apparent towards the end of the season, when further strong winds caused the beans to be scratched and bruised to the extent that they were unfit for processing. This is names a factor growers must give full consideration to in future, when selecting their site for a prospective pole bean garden.

Techniques of growing pole beans seem to vary from garden to garden, and from district to district. In this district most growers this season used the fine cotton string for the first time, and in nearly every case it would be true to say that they were favourably impressed with the suitability and low cost of the new material. The use of a non-shrinking paper string in place of the bottom wire was not a success, as the string did not live up to its reputation. The recommended string used in the U.S.A. could not be obtained. However, the principle of a string in place of the bottom wire is sound, and no doubt we will be able to pFactory Firsts: 2urchase the correct type of string for future seasons.

POSTS AND WIRE.

Number 12 gauge fencing wire was of adequate strength for the top wire, although where the strain was greater than 50 yards breakages did occur. One grower who was faced with this problem reduced the length of the strain by making ties at every 50 yds. The tie was made by cutting the wire at the required length and anchoring it to the foot of the following post as illustrated in a diagonal pattern.

The spacings for posts in the rows averaged 30ft. apart. Posts set at wider distances gave a much weaker support, and cases were seen where the fences collapsed when the beans were at the peak of their production. This was particularly so after a heavy shower of rain.

A very good method which is worth mentioning here is one used in the Nelson district, where the main posts are spaced at 60ft. apart in the rows and two stakes which act as props are spaced in between these main posts. At the foot of each stake a piece of case board is nailed to the bottom so that it is not forced into the ground with the weight of the crop. This method would require fewer main posts per acre, and would give a fence which is sound enough to support the crop.

Row spacings varied from 5ft. apart up to 7ft. The optimum distance for the maximum production would be difficult to ascertain, but it would probably fall between the 5ft. and 6ft. figure. However, growers normally determined their row spacings by the type of machinery they had available.

The most common types of post used were poplar and willow. These have only a very sho namesrt life, and growers who intend growing pole beans for a number of seasons would be well advised to use more durable posts. We can give growers long-term contracts for pole beans, so that there should be no need for any uncertainty upon investing in sound posts which will last for a number of years.

Next season we will be requiring an even greater tonnage of pole beans. Growers in the past have been hesitant to grow these beans, mainly because of the extra work and extra expense involved per acre, as compared with dwarf beans. Costs per acre will vary from grower to grower, depending on whether or not he has a cheap source of poles or inexpensive irrigation, and so on.

COSTS. names

The costs as set out are based on the average production per acre last season. Dwarf beans varied from 1 ton per acre up to 6 tons, with the average falling at 3.8 tons; while for pole beans production varied from 4 tons per acre up to 12 tons, average 7.5 tons per acre. With a gross return of £46/13/4 per ton, this would return to the grower £163/6/8 for dwarfs and £350 for poles. The average material and labour costs for both types of beans are set out below: –

DWARF BEANS.

£. s. d.

Seed at 1 bushel per acre 6 0 0

Fertiliser, 1cwt. Super per acre 2 0 0

Cultivation, approximately per acre 10 0 0

Hand Weeding per acre 20 0 0

Picking at 2d. per lb. 63 0 0

Balance Net Profit 62 6 8

Gross Intake 163 6 8

POLE BEANS.

Seed at ½ bushel per acre 3 0 0

Fertiliser, cwt. Super per acre 2 0 0

Posts at 200 per acre 30 0 0

String 5 0 0

Wire at 1¼cwt. per acre, No. 12 5 0 0

Cultivation approximately per acre 15 0 0

Hand Weeding 10 0 0

Picking at 2d. per lb 135 0 0

Extra Labour for Stringing, Wiring and Posts 30 0 0

Balance – Net Profit 115 0 0Factory Firsts: 2

Gross Intake £350 0 0

These costs and returns are only a guide, but from them it can be seen that a grower may expect almost twice the net profit from an average crop of pole beans as he would from an average crop of dwarfs. Such items as posts and wire which have been debited against the net return from pole beans, are really a capital asset, and their cost should not be written off in one year. If this were allowed for there would be an even greater margin of profit shown for pole beans.

Factory Firsts: 2

TOMATO PEELING MACHINE.

Tomato products have featured prominently in the development of J. Wattie Canneries Ltd. almost from the origin of the company. During a severe frost in 1936, tomatoes were grown to keep the wheels turning when fruit was not available. The venture proved sound, and the company’s tomato products have extended their popularity ever since. Sales increase year by year, and Watties are proud to be the Dominion’s largest producers of tomato products in a wide variety.

Whole peeled tomatoes are popular in this wide range. To further improve the quality of this pack, J. Wattie Canneries Ltd. were the first factory outside the U.S.A. to operate an automatic tomato peeling and coring machine. It has operated over the past two seasons and has given a new look to this pack. The machine being automatic, the tomato is not subjected to handling and goes into the can looking smooth and uniform.

Tomatoes are specially selected and fed into the machine by hand. The tomato then goes through a bath to loosen the skin. It is then transferred to a rubber cup while the core is reamed out. While still held in the cup it is twisted, which further loosens and breaks the skin. Thence it passes under high water pressure nozzles which completely remove the skin, leaving the tomato beautifully clean and smooth, ready for packing into the can. The process assures the highest possible quality of canned whole-peel tomatoes and has the special virtue of being completely hygienic.

PEACH TREES SCARCE

The production of peaches for canning is increasing rapidly. This year the demand exceeds by far the supply. Many prospective growers have been unable to plant because trees were not obtainable. The position next year will not improve greatly. To avoid disappointment growers would be well advised to contact our field staff immediately. If we know your requirements in time we can assist you.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

The donor of this material does not allow commercial use.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.