- Home

- Collections

- MOODY M

- Books, Articles

- Hawke's Bay Earthquake, The

Hawke’s Bay Earthquake, The

Earthquake ’31 Page 3

The day of destruction

Hawke’s Bay had known disaster. There had been floods. A great fire in 1886 had destroyed much of Napier’s business area.

But nothing was as shattering and total as what occurred at 10.47am on Tuesday, February 3, 1931.

Two mighty shakes, just 30 seconds apart, paralysed the province and killed 258 people in New Zealand’s greatest natural disaster.

Rail and road links to the outside were severed, telephone and electricity supplies cut, Napier’s inner-harbour port crippled, and buildings demolished in an area from Wairoa to Waipukurau.

For Napier, still worse was to come. Within minutes of the first earthquake – magnitude 7.9 on the Richter scale – fires started in the main business areas in Emerson Street and Ahuriri. By the time they finally spluttered out, 10 acres of Napier’s central business area had been gutted.

Six-hundred-and-seventy-four aftershocks over the next two months were a constant reminder of the trauma of those first hours.

The earthquake and fires caused damage assessed in 1931 values at $9.7 million. In the currency of the late 1990s it would have been nearly $900 million.

Napier bore the brunt of the earthquake, and 162 of its people perished, but Waipukurau, Hastings, Waipawa and Wairoa were also hit hard.

In a few seconds 900 chimneys came crashing down in Waipukurau, the post office clock tower was wrecked and the brick frontages of many businesses collapsed.

In Wairoa the huge upheaval saw shop fronts give way and wooden buildings close to the waterfront collapse, while the town’s traffic bridge across the river was destroyed. Three people lost their lives in the Wairoa area.

In Hastings a large portion of Heretaunga Street was laid to waste as buildings collapsed, and more than 90 people died.

Those who emerged unscathed were stunned and shattered by the experience. In communities the size of Hawke’s Bay’s towns of those days, few did not suffer the loss of family members, other relatives or friends.

The tumble of masonry which caused the first casualties is vividly remembered by Miss Nancy Hobson, who was inside her father’s chemist shop under Napier’s old Masonic Hotel.

Fifty years later she re-called: “I felt it coming. My first instinct was to run outside. I had barely got on to the road when the whole face of the hotel fell.

“It was like being on the deck of a ship in rough seas. You didn’t know where your feet were going to hit the ground.

“I tripped on wires and fell over people. I couldn’t control my walking at all. It was very dark and there was this extraordinary roar of falling masonry that went on for a very long time.”

These were the conditions which killed so many people fleeing to escape the violently rocking buildings. Facades, cornices and parapets – popular architectural decorations of the time – toppled and struck death blows.

Several days later a journalist witnessed workmen removing a mound of rubble from what had been the entrance to the Masonic Hotel. He told readers that seven bodies were found “huddled together where they had tried to rush from the building”.

In some ways an even more horrific fate awaited many who never made it to the streets.

Maimed, pinned down, or simply trapped inside buildings, they were at the mercy of fires which broke out in several chemist shops around town and which soon engulfed the whole main business centre of Napier.

Desperate attempts to save them were doomed by the heat of the fire or the weight of the rubble.

Fireman, sailors, policemen and civilians heard the screams of people perishing in the flames.

The search for survivors began immediately. Townspeople were joined by crew from HMS Veronica, which happened to be berthed at the port.

Fire-fighting soon became almost impossible, mainly through a lack of water resulting from broken water mains.

Residents left their homes. Many camped on the beachfront; others gathered in groups on front lawns and other open spaces as the lesser earthquakes continued.

Open areas such as the racecourse at Greenmeadows became a field hospital: Nelson Park was designated a refugee centre.

As Napier and Hastings started to organise relief work, offers of assistance poured in from the whole of New Zealand.

The naval vessels HMS Dunedin and Diomede sailed with relief equipment and workers from Auckland. Within hours, medical and relief work was proceeding at pace with volunteer agencies such as the Red Cross at the centre of activity.

Initially the earthquake cut all road communications between Napier and Hastings and the rest of the country, with the exception of what is now State Highway 2, from Hastings to Wellington.

The Wellington-Napier railway line remained intact up to Ormondville in Central Hawke’s Bay. Telegraph communication reached into the province as far as Waipukurau.

The severity of the shake put much of the automatic telephone equipment out of alignment – rendering it useless – and the disruption to power services from the Waikaremoana and Mangahoa power stations left much of the province without power.

Outside assistance was desperately needed and no time was wasted in getting the vital telegraph lines and railways back into operation.

Though most parts of New Zealand had felt the quake to some extent, the only immediate word to the outside world hinting at the severity of what had happened in this area was a radio message from the Veronica. One of its signallers relayed the message: “Medical assistance required; fear considerable loss of life.”

The Post Office moved quickly to re-establish telegraphic links. Repair gangs left Wellington by road within hours of the alert and reached Hastings the following day.

Photo captions –

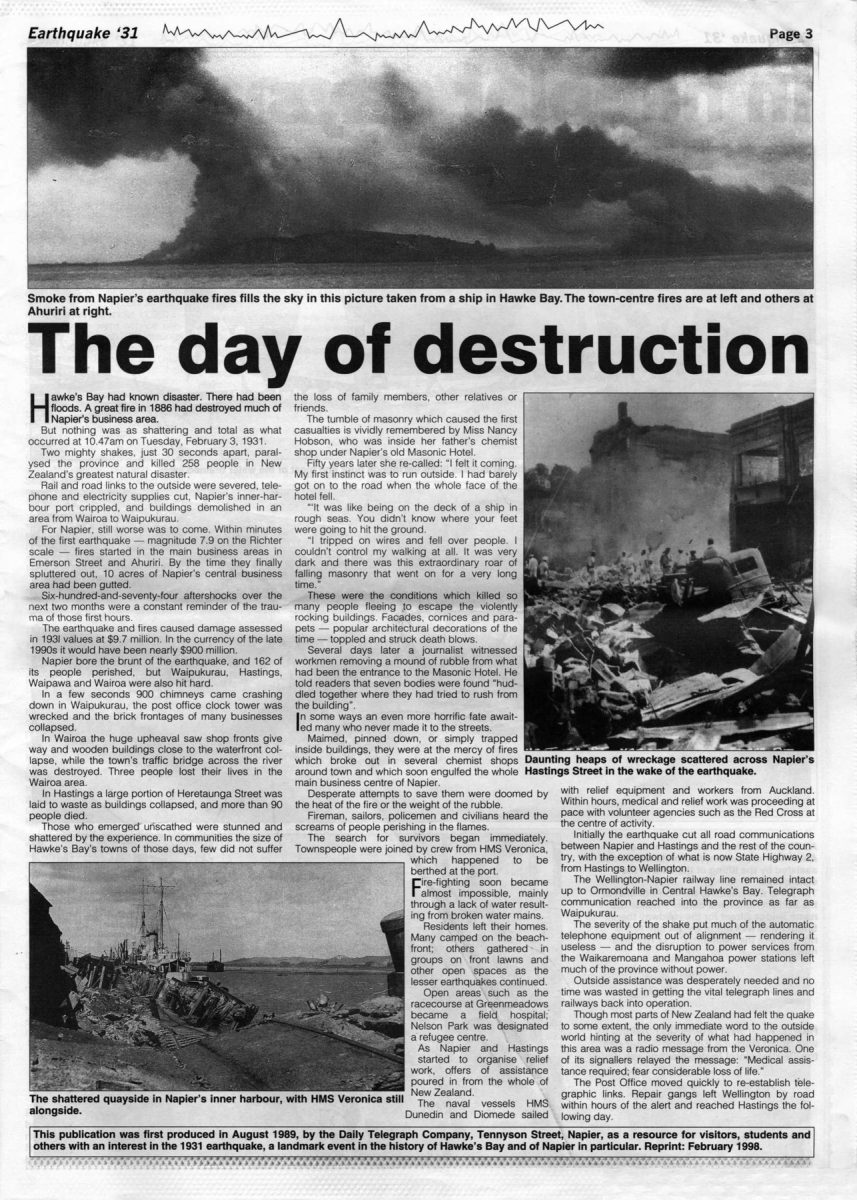

Smoke from Napier‘s earthquake fires the sky in this picture taken from a ship in Hawke Bay. The town-centre fires are at left and others at Ahuriri at right.

Daunting heaps of wreckage scattered across Napier’s Hastings Street in the wake of the earthquake.

The shattered quayside in Napier’s Inner harbour, with HMS Veronica still alongside.

This publication was first produced in August 1989, by the Dally Telegraph Company, Tennyson Street, Napier, as a resource for visitors, students and others with an interest in the 1931 earthquake, a landmark event in the history of Hawke’s Bay and of Napier in particular. Reprint: February 1998.

Earthquake ’31 Page 4

In happier days…

Photo captions –

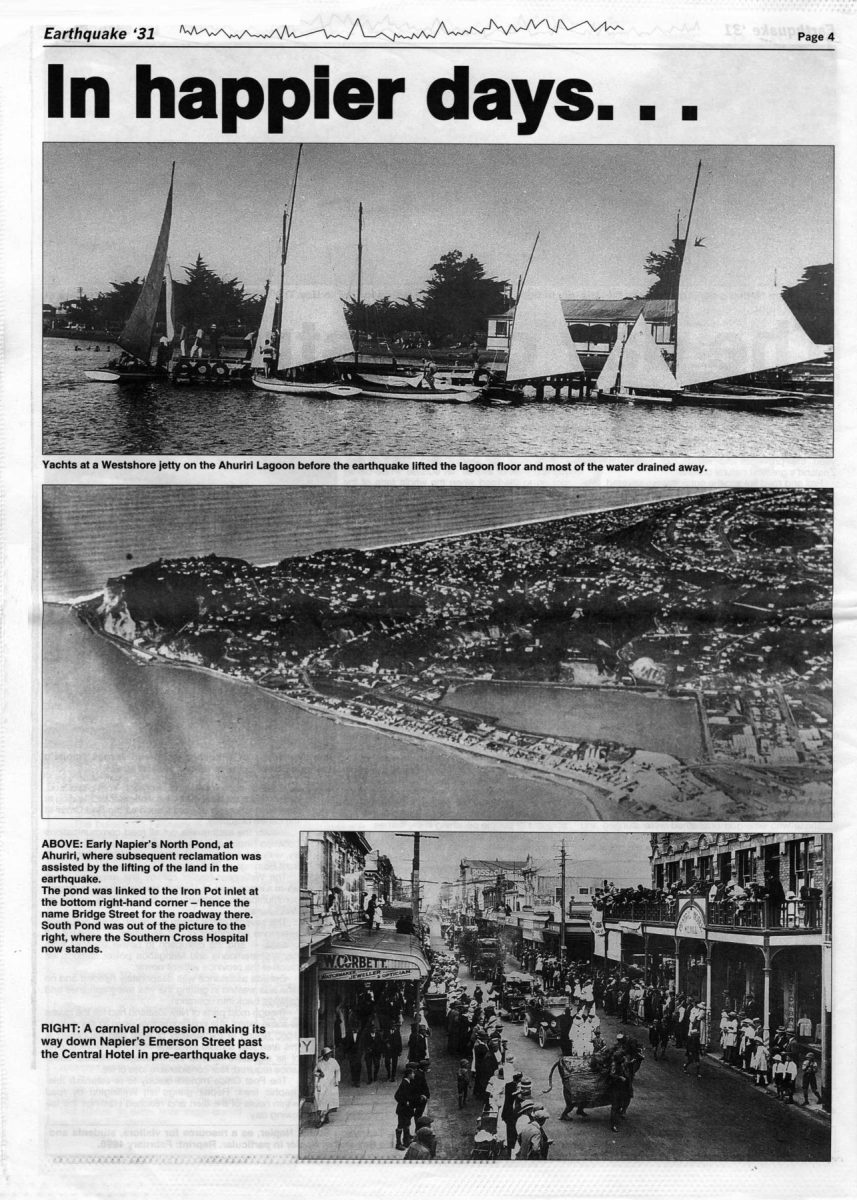

Yachts at a Westshore jetty on the Ahuriri Lagoon before the earthquake lifted the lagoon floor and most of the water drained away.

ABOVE: Early Napier’s North Pond, at Ahuriri, where subsequent reclamation was assisted by the lifting of the land in the earthquake.

The pond was linked to the Iron Pot Inlet at the bottom right-hand corner – hence the name Bridge Street for the roadway there. South Pond was out of the picture to the right, where the Southern Cross Hospital now stands.

RIGHT: A carnival procession making its way down Napier’s Emerson Street past the Central Hotel in pre-earthquake days.

Earthquake ’31 Page 5

The scene is set

Europeans had been properly settled in Hawke’s Bay for less than 100 years when the earthquake which caused so much destruction to their homes and town centres struck.

They had established themselves in Napier and Hastings, with smaller towns at Havelock North, Taradale, Waipukurau, Waipawa and Wairoa.

Hawke’s Bay was not a crowded province. Napier had a population of just over 16,000 in 1931; Hastings had just under 11,000.

Both towns were service centres for the rich Heretaunga Plains, where there was mixed and pastoral farming, and fruit-growing. Both towns also had modest processing and manufacturing industries.

In both, the 1920s had seen a building boom and an upsurge in motor traffic, and Napier was also served by electric trams.

Napier was established at Onepoto Gully in 1844 and grew over the years on and about Scinde Island, a dominating limestone hill known by the Maori as Mataruahou.

The business heart of the town was, as it still is, immediately to the south of Scinde Island; the housing extended further south, narrowing to an isthmus near the Napier Boys’ High School.

Inland of the isthmus was marshland, though a roadway straddling this ran through to Taradale.

There had already been some reclamation here of the shallow, salt-water, marshy lagoons. Such work had got rid of some of the “variety of noxious and pestilential gases” which the Provincial Surgeon had identified in 1860.

He had been unimpressed with the site of Napier. His comments on it read: “Exhalations from this porous crust can scarcely be considered compatible with the preservation of health; neither is it so, and when the town has increased considerable apprehension may be entertained that they will prove a fertile source of fevers, agues, diarrhoea, rheumatism…”

On the west side of the island was the Ahuriri Lagoon, 3000 hectares of tidal mudflats, a popular area for beach picnics and yachting.

The Port of Napier, meanwhile, was divided into an inner harbour and an outer one. This situation was reflected in two factions in Hawke’s Bay, one of people seeking development of the inner harbour, the other supporting the outer harbour.

That was a situation eventually resolved by the earthquake.

Nineteen kilometres south of Napier and 10 kilometres from the sea was Hastings, originally called Heretaunga when it was settled in 1864.

Hastings then was similar to a typical, small English market town; its satellite township of Havelock North was a popular retirement centre and the location of various private schools including Woodford House, Iona College and Hereworth School.

Much of the development in and around Napier took place during the latter half of the 19th century. For example, the first post office was set up in 1852, at Port Ahuriri.

Also during that decade, coach links with surrounding areas were established and the 19-year-long construction of the Taupo road started.

Electric telegraph links with Wellington were established in 1867; in the 1870s Napier came in line for railways development.

In February 1875, the nine-member Napier Borough Council had its first meeting; around the same time, the Napier Gas Company was established.

Improvements to the Marine Parade were carried out in the 1890s, and in the early 1900s the borough council began raising major loans to pay for various civic amenities such as cemeteries, bridges, parks and a library and fire station.

Hastings experienced slightly later growth. There was little early European demand for land there. However, the area had grown enough by 1883 to have the right to elect a town board.

The work of 30 years was virtually destroyed in 1893, when a fire ravaged much of the town.

As is noted in the historical book Hawke’s Bay Before and After: “The years still rolled on, and gradually Hastings was transformed from just an ordinary town to something worth while.

“New buildings were erected, the town was beautified, good permanent streets were put down, parks were put in order, good street and community lighting was introduced, a women’s rest and hospital were erected and in many of these reforms Hastings was able to show points to practically every other town in the Dominion.”

In the immediate lead-up to the 1931 earthquake Hawke’s Bay was gripped by drought and the world-wide depression. Livestock and consumer goods were all fetching low prices.

And also taking people’s attention, before the earthquake swept all else aside, was a January 31 fire which razed the public hall and library at Clive, the jailing and release of Mahatma Gandhi in lndia, the emergence of dictator Mussolini in Italy, the United States successes of racehorse Phar Lap, and Hawke’s Bay cricketer Tom Lowry’s selection to captain a New Zealand team to visit England.

Photo captions –

A band plays serenely at the junction of Tennyson Street and Marine Parade in pre-earthquake Napier.

Traffic-busy Heretaunga Street, Hastings, before (above) and after (below) the earthquake.

RIGHT: The cleaned-up ruins of Napier. The L-shaped Post Office building on the corner of Hastings and Dickens Street, at top right, was the only major building to survive in the pictured area. Nearest the camera is Tennyson Street, with Emerson street beyond.

Earthquake ’31 Page 6

Why the earth quakes

George Eiby, a retired superintendent of the Seismological Observatory of the former Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Wellington, looks at the lessons of the 1931 earthquake in the light of a further half-century of research. Mr Eiby died in 1992.

Earthquakes are as inescapable as the weather. Even Mars: and the Moon have them.

Here on Earth, seismologists report that every year there are a couple of million of them strong enough to be felt, a thousand or so that could bring down chimneys, and a dozen potential disasters. It’s just as well that so much of our earth is ocean, mountain desert, or uninhabited forest so that our chances of being hit by a big one are small enough.

How is it then that we keep reading of distant disasters that kill a hundred times more people than all New Zealand shocks taken together? The answer is not bigger earthquakes, but poorer buildings!

One of the earliest lessons from the Hawke’s Bay earthquake was the need for strict building laws, and our engineers have come to be among the leaders in the art of designing earthquake resisting structures.

There has also been astonishing progress in understanding how and why earthquakes happen. Some seismologists are raising hopes that reliable earthquake forecasting is not far away. Others insist that forecasting is a side issue; that there is little point in predicting when cities will fall down, and that we should concentrate upon making them stand up.

Both schools of thought agree that we need a sound knowledge of the habits of earthquakes.

Piecing the earthquake story together has been a long business, and we have yet to reach the end of it. As long ago as the 18th century John Michelle realised that waves travelling through the solid Earth were responsible for shaking down buildings, and suggested ways of tracing them back to their source. By about 1900 recording instruments had been invented, and we had learnt a great deal more about the kinds of waves involved, and how they travelled.

We also knew that the shocks were a consequence of the processes that built mountains and shaped the face of the Earth. Rocks far underground were fractured and set off the seismic waves. If the shock was big enough and shallow enough, a great crack could break through to the surface and appear as what geologists call a fault.

After the big San Francisco earthquake in 1906, H F Reid examined the displacements of the ground near the San Adreas [Andreas] Fault, and realised that what had happened was an “elastic rebound”. A long, slow accumulation of strain had finally brought the rocks to breaking-point, and released the stored energy. The earthquake was not something sudden and abnormal, but a return to normal from a condition of strain.

That the strains are going on is clear enough from the folds and fractures that can be seen in rocks almost anywhere, but where do they come from? During the last few years, earth scientists have arrived at an explanation they call “plate tectonics”.

As with most important scientific theories, the basic ideas of plate tectonics are simple, but they turn out to explain most features of the earth’s surface, from the broad pattern of continent and oceans to earthquakes, volcanos, and the deep trenches in the ocean floors.

Great fractures have been found to divide the outermost layers of the earth into about seven large, rigid plates which float on the more plastic material of the mantle underneath. The Earth’s internal heat keeps this more plastic material in and moves outward toward the margins of the continents as it cools. There it descends into the mantle once more, and is melted and reabsorbed.

The plates are carried along by this movement, which brings their edges into collision, folding and fracturing them, and producing belts of earthquakes and volcanoes. Because they are rigid, the central parts of the plates are comparatively stable.

New Zealand lies at the meeting of two plates.

To the west, the Indian Plate carries both Australia and India, while to the east the Pacific Plate forms the North Island.

This thrusting accounts for the Hawke’s Bay earthquake of 1931 and, indeed, for all the earthquakes in the northern half of the South Island.

In Fiordland, the same forces are responsible, but there it is the Pacific Plate that is on top, and the Indian Plate that is being driven beneath it. The complexities of the transition are a subject of lively scientific argument.

Since European settlement began, New Zealand has had about 15 earthquakes within half a magnitude or so of the size of the Hawke’s Bay one, yet only the Murchison shock in 1929 produced casualties running to double figures, and none has caused comparable damage to property. Why was it so destructive?

The short answer is that its origin was unusually close to centres of population, and close to the surface. In places where a plate is being thrust back into the mantle, very deep shocks are often found. New Zealand’s deepest – under north Taranaki – were more than 600km down; but the great majority of shocks, including all the destructive ones, originate within the crust, about 30km thick.

In 1931, there were few good seismographs in New Zealand, and we had to get most of our information about the Hawke’s Bay earthquake from overseas recordings, so it would be rash to be too dogmatic about the position of the origin.

The best estimates put the epicentre (the point on the surface directly over the origin) between Rissington and Patoka, about 25km north-west of Napier, but this could be as much as 20km out in any direction. The depth was no more than 15 or 20km.

The magnitude of the shock was 7.9, about the same as that of Murchison earthquake two years earlier. It is not the country’s biggest shock, that distinction going to the south-west Wairarapa earthquake of 1855, which had a magnitude of at least 8. The Inangahua earthquake in 1968, the last of New Zealand’s really serious shocks, reached only 7.1.

There is more to a big earthquake than an underground breaking of rocks and the radiation of a train of waves. The whole of the earth’s rust [crust] must readjust, with consequent uplifts and subsidences, and a sequence of aftershocks that may persist for a year or more. In Hawke’s Bay two common accompaniments of a large shock were missing – a tsunami (or seismic sea-wave) and visible displacements along a geological fault.

The curious disruption of the tides and the draining of the Ahuriri Lagoon were not the result of a tsunami, but of the regional uplift that was a permanent result of the earthquake. An area some 90km long and 15km wide was raised by a maximum of about 3 metres. There was also settlement of poorly compacted land near the mouth of the Tutaekuri River and on the Heretaunga Plains.

Could it happen again? So far as the geological story is concerned, the answer is yes, the movement of the plates is not going to stop.

Hawke’s Bay will have more earthquakes and a few of them will be as big or bigger than the one in 1931. What need not be repeated is the loss of life and property. We know how we should build, and where we should build to withstand even the strongest likely shocks.

Are we wise enough to apply our knowledge?

Maps text –

PLATES THAT MOVE THE EARTH’S CRUST

EURASIAN PLATE

INDO-AUSTRALIAN PLATE

ANTARCTIC PLATE

ANTARCTIC PLATE

PACIFIC PLATE

NORTH AMERICA PLATE

NAZCA PLATE

Major Earthquakes

(since 1843)

Record of death and destruction

Dates, locations and Richter-scale magnitudes of the major New Zealand earthquakes since 1843, with the death tolls in brackets in the nine cases where lives were lost:

1843, July 8, Wanganui, 7.5 (2)

1848, Oct 16, Marlborough, 7.1 (3)

1853, Jan 1, New Plymouth, 6.5.

1855, Jan 23, South Wairarapa, 8.1 (5).

1863, Feb 23, Hawke’s Bay, ?

1876, Feb 26, Oamaru, ?

1888, Sept 1, North Canterbury, 7.

1891, June 23, Waikato, 6.

1895, Aug 18, Taupo, 6.

1897, Dec 7, Wanganui, 7.

1901, Nov 17, Cheviot, 7 (1).

1904, Aug 9, off Cape Turnagain, 7.5.

1914, Oct 7, East Cape, 7-7.5, (1).

1914, Nov 22, East Cape, 6.5-7.

1917, Aug 6, Nth Wairarapa, 6.

1921, June 19, Hawke’s Bay, 7.

1922, March 9, Arthur’s Pass, 6.9.

1922, June 19, Taupo, ?

1929, June 16, Murchison, 7.8 (17).

1931, Feb 3, Hawke’s Bay, 7.9 (258).

1931, May 5, Poverty Bay, 6.

1932, Sept 16, Wairoa, 6.8.

1934, March 5, Pahiatua, 7.6, (1).

1942, June 24, Sth Wairarapa, 7.

1950, Feb 5, south of the South Island, 7.

1950, Aug 5, south of the South island, 7.3.

1953, Sept 29, Bay of Plenty, 7.1.

1955, June 12, Seaward Kaikouras, 5.1.

1958, Dec 10, Bay of Plenty, 6.9.

1960, May 24, Fiordland, 7.

1962, May 10, Westport, 5.9.

1963, Dec 23, Northland, 5.2.

1966, March 5, Gisborne, 6.2.

1966, April 23, Cook Strait, 6.1.

1968, May 24, Inangahua, 7 (3).

1972, Jan 8, Te Aroha, 5.1.

1974, April 9, Dunedin, 5.

1981, April 14, under Lake Taupo, 6.

1981, May 25, 400km sth-west of Stewart Island, 6.4.

1981, Nov 17, nth-west of White Island, 6.3.

1981, Dec 28, Cape Turnagain, 5.7.

1982, Oct 30, Taranaki, 5.7.

1983, Jan 27, Kermadec Islands, 7.3.

1984, March 8, north-west of Gisborne, 6.4.

1984, Dec 30, east of Coromandel, 6.3.

1986, Oct 27, Lake Taupo, 5.9.

1987, March 2, Edgecumbe, 6.3.

1987, March 22, near Mayor Island, 6.1.

1988, June 4, Te Anau, 6.6.

1989, May 31, Otago, 6.6.

1989, July 7, north of Whakatane, 5.8.

1989, Aug 8, Patea, 5.8.

1989, Nov 30, Gisborne, 5.0.

1990, Feb 10, Lake Tennyson, 5.9.

1990, Feb 19, Weber, 5.8.

1990, March 28, Rotorua, 5.9.

1990, May 13, Weber, 6.0.

1990, Aug 16, Weber, 5.2.

1990, Oct 5, Cape Palliser, 5.6.

1990, Oct 6, Cape Palliser, 5.6.

1990, Oct 20, Lake Tennyson, 5.5.

1991, Jan 28, Westport, 6.3.

1991, Jan 29, Westport, 5.9.

1991, Feb 15, Westport, 6.0.

1991, July 12, Taupo, 6.2.

1991, Sep 8, Bulls, 6.3.

1992, March 2, Porangahau, 5.8.

1992, May 27, Blenheim, 6.7.

1992, June 21, Bay of Plenty, 6.1.

1993, April 11, Te Hauke, 6.1.

1993, Aug 10, Gisborne, 6.7.

Earthquake ’31 Page 7

Earthquake scientists look now to sky

The surface of the Earth in New Zealand is restless and almost constantly on the move.

It is rising in Hawke’s Bay, but sinking in the Marlborough Sounds.

It is extending in some regions, contracting in others.

During an earthquake this movement is very rapid, but the build-up of elastic strain beforehand is very slow and may take hundreds of years. On a wider and grand scale, the plates just drift across the surface of the globe at speeds of tens of millimetres a year. The crunch comes in the plate boundary regions – of which Hawke’s Bay is a part.

There are a number of ways to keep track of the shape of this mobile Earth. In the past, surveyors have used theodolites to measure the relative positions of trig points – sighting from hill-top to hill-top. Others have levelled routes along railways and across country to establish accurate heights.

Allan Hull, in his 1985 Victoria University of Wellington research thesis, used the levelling observations made before and after the Hawke’s Bay earthquake to sort out the north-east trending, elongated pattern of uplift and subsidence.

There was a maximum uplift of nearly three metres at Old Man’s Bluff near Aropaoanui and a maximum subsidence of one metre near Hastings. The line of ‘no change’ ran from Bridge Pa through Awatoto to the Waihua River and may be related to a buried fault on which movement of some metres took place.

Similarly, the horizontal movements of trig stations have been observed, both in the Hawke’s Bay region and elsewhere.

But these land-based measurements are being overtaken by space-based or extra-terrestrial ones. Tomorrow’s geophysicists and surveyors will look to the skies – to a constellation of satellites 20,000 kilometres above the Earth’s surface.

The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based positioning system which uses the US Navstar satellites to provide precise locations and heights.

The satellites carry very precise atomic clocks and continuously broadcast a coded signal, which is monitored by small, portable receivers. These receivers, though at first expensive, are rapidly lessening in price.

Provided the orbits of the satellites are precisely known from tracking stations around the Pacific, it is claimed that, with a network of receivers in New Zealand, locations can be made with an accuracy of 10-30mm, horizontally and vertically.

The Department of Lands and Survey already has some receivers, Victoria University Earth scientists are collaborating with overseas scientists who will be bringing receivers to New Zealand, and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research is involved.

The Royal Society of New Zealand is updating its overall plan for the study of earth deformation.

Over a period of years, we hope, using GPS, to be able to see the drift of the plates and see the Chatham Islands moving towards the East Coast at about 50mm a year. We will see the ongoing deformation of the East Coast region itself, and the build-up of elastic strain.

Longer term, we want to answer the most important question: How much of the relative movement between the plates is taken up by large earthquakes and how much is taken up by plastic flow or a seismic slip without earthquakes?

The answer will tell us much about how often we might expect large earthquakes, and part of the answer may lie in the sky.

Still learning about the events of 1931

For every earthquake of the magnitude of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake there are in the same region a million smaller earthquakes which are mostly unfelt.

The small ones are called micro-earthquakes and have a magnitude of only one to three on the Richter scale.

Since 1970, seismologists from Victoria University and the Seismological Observatory (DSIR) have been using very sensitive portable seismographs to detect these micro-earthquakes, to determine the rate of activity, its location and the stresses involved.

The waves from these earthquakes are also used to find the properties of the rocks between the earthquakes and the seismographs.

Now, in the 1980s, the cause and nature of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake is finally being understood by the seismologists. This understanding is coming from a wide range of observations and their interpretation. These sources include: Micro-earthquakes; 1931 seismograms from overseas; 1931 deformation; oil prospecting in Hawke’s Bay; plate tectonics and gravity surveys.

From the global motions of the plates, we find that the Pacific plate to the east of Hawke’s Bay is moving north-west at about 85 millimetres a year. This plate is being carried down (subducted) under Hawke’s Bay, beginning in the Hikurangi Trough 150km south-east of Cape Kidnappers. The subducted plate lies 23km under Napier, and about 80km under Ruapehu, and dives down to a depth of 350km.

The overlying plate to the west, of which Hawke’s Bay is just the deformed edge, is called the Indo-Australian plate and is a rigid plate under-lying the Tasman Sea and including the continent of Australia. This plate is moving northward, away from Antarctica.

So, though the subduction under Hawke’s Bay is toward the north-west, the relative motion between the plates is convergence in the east-west direction at about 50mm a year.

In the ranges rising to the west of Hawke’s Bay there are several massive active faults. The Mohaka fault runs north north-east between Patoka and Puketitiri; the Ruahine fault runs along the front of the Black Birch range. These faults are nearly vertical and the relative motion on them is such that the east side moves south. They cut right through the overlying plate, down to the plate boundary below.

During the Hawke’s Bay earthquake, no major fault broke the surface. The main permanent deformation was an uplifted dome more than 90km long and 30km wide, trending north-east and with a maximum up-life [uplift] of nearly three metres. This raised area was separated from a narrow zone of subsidence to the south east, which including Hastings, by the line of no-change from Bridge Pa through Awatoto to the Waihua River.

From seismograms recorded around the world in 1931, it was found that the earthquake triggered beneath Patoka at a depth of around 17km.

Over 50 years later, in 1983 and 1984, Stephen Bannister undertook micro-earthquake surveys in the Hawke’s Bay region as part of his research at Victoria University toward a PhD. The locations of the earthquakes he recorded and the seismic waves from them have helped to locate the plate boundary beneath Hawke’s Bay.

He found from oil exploration work that the top 5km of the Earth’s crust in Hawke’s Bay is relatively weak and that there is evidence of a major, steeply dipping fault buried beneath the surface sediments.

Computer modelling by DSIR geophysicists have shown that the observed uplift pattern from the Hawke’s Bay earthquake is consistent with about 7 metres of slip on a buried fault, which trends north-east and dips steeply toward the north-west.

The 1931 fault rupture was triggered about 17 kilometres deep beneath Patoka. It sent seismic waves racing out in all directions at about six kilometres, a second, hitting Hawke’s Bay above and heading for Europe below.

Meanwhile, the fault rupture spread out at about half this speed, ripping along the existing fault towards the surface of the Earth and to the north-east and south-west.

The fault break stopped short of the surface. The weak surface rocks deformed and draped over the buried fault, causing uplift and subsidence. Many people noticed the few seconds’ gap between the start of the shaking and the buckling of the ground.

This, many years on, is a seismologist’s view of these dramatic events.

We are learning from the past, to prepare for the future.

Diagrams text –

GLOBAL POSITIONING SYSTEM

NAVSTAR SATELLITE

PACIFIC PLATE

50mm/YEAR

Hikurangi Trough

Mt Ruapehu

Sea level

Hikurangi Trough

INDO-AUSTRALIAN PLATE

HB Quake

PACIFIC PLATE

S.E.

Photo caption – Jim Ansell, a former professor of geophysics at Victoria University of Wellington, prepared the material on this page especially for this publication. Professor Ansell was an old boy of Napier Boys’ High School. He died in 1993.

…part of Napier’s Architectural Heritage.

The Rothmans Building was designed by Louis Hay (1881-1948) and built by the Faulknor Brothers in 1933 for Mr Gerhard Husheer, Managing Director, National Tobacco Co. Ltd. Mr Hay was a director on the National Tobacco Company board at the time of the Hawke’s Bay Earthquake. One of the best descriptions of the building is contained in Peter Shaw’s book Art Deco Napier: Styles of the Thirties*.

“Perhaps Louis Hay’s best-known building is the National Tobacco Co of 1934, now owned by Rothmans. In this Hay employed a distinctly Sullivanesque scheme of placing an arch within a square, in accordance with the wishes of his client, Mr Gerhard Husheer, that the building be simple in form yet elaborately decorated. Hay had already remodelled three houses at the end of Elizabeth Road for this wealthy client, and had leadlight designs returned to him by Husheer on the grounds that they weren’t fancy enough. The National Tobacco Co building shows no such restraint, covered as it is with cleverly placed clumps of sculpted concrete roses. On either side of the highly decorated doors, carved by Gwen Nelson of Havelock, the roses are combined with raupo into a pleasing but unlikely arrangement. The two piers of the arch display the Art Deco undulating wave motif Hay had already used on the Hildebrandt Building. Vine leaves and bunches of grapes also feature. The gleaming brasswork of the banisters, the rich woodwork of the doors, the ornate lamps and the speckled marble foyer with its beautiful glass dome make this Napier’s most luxurious post-earthquake building. Obviously no one demanded restraint of the architect, the Depression seemingly an irrelevance to this client.”

* Art Deco Napier: Styles of the Thirties, Peter Shaw (text), Peter Hallet (photographs)

FIRST PUBLISHED (REED METHVEN [METHUEN[ 1987).

Earthquake ’31 Page 9

ABOVE: The ruins of the Municipal Theatre dominate this view of central Napier after the immediate clean-up of the earthquake debris. Beyond are three of the survivor buildings – the public Trust, behind it the E and D Building (now Hallenstein’s) and, to the right of that, Dalgety’s building (now occupied by Classic Hits 89FM).

RIGHT: Damage to the Mt St Mary’s Seminary chapel at Greenmeadows, where two priests and seven students were killed by falling debris.

BELOW: Collapsed wards at the Napier Public Hospital.

EQC

WHAT IS EQC?

The Earthquake Commission (EQC) is the new name of the old Earthquake and War Damage Commission. EQC is a Crown Entity which has the job of providing EQCover, including collecting premiums and paying claims. EQC has a Disaster Fund for the payment of claims. This is currently worth over $2.3 billion. EQC has also arranged its own overseas reinsurance cover in case of catastrophic earthquake and, if that is not enough, the Government is required by law to make up any shortfall.

WHAT IS EQCOVER?

EQCover is the natural disaster insurance scheme available from the Earthquake Commission (EQC) (Previously the Earthquake and War Damage Commission) from 1 January 1994.

EQCover insures homes (including flats and holiday homes), personal belongings, and the land the homes are on.

EQCover insures against earthquake, natural landslip, volcanic eruption, hydrothermal activity and tsunami.

EQCover also insures damage caused by storm or flood to residential land (but not to the home or belongings).

EQCover applies only to residential homes which are insured against fire.

HOW DO I GET EQCOVER?

When you buy a houseowner’s policy for your home, or insure your personal belongings, your insurance company has to charge a disaster insurance premium, which it passes on to the Earthquake Commission (EQC). This gives you EQCover.

WHEN WILL I GET EQCOVER?

EQCover is a new scheme which started on 1 January 1994. Cover under the old scheme will continue for your home and personal belongings until your insurance policy expires during 1994. At that time, if the policy is renewed, your cover with EQC will change automatically to the new scheme.

Your insurance company will send you a renewal notice shortly before the date applicable to you. We have asked them to include an EQC brochure, at that time, to remind you of the changes.

HOW MUCH COVER DO I GET?

EQC insures your home on a replacement value basis, but there are limits to the amount you can claim (and on which you pay premiums).

These limits are the least of the following:

– the amount for which you have insured your home on a replacement basis (ie, the replacement sum insured);

– if your fire insurance policy does not have a replacement sum insured, an amount specified by you in the policy for EQCover on your home or holiday home (which cannot be less that [than] $1000 per square metre of floor area).

– $100,000 per dwelling.

EQCover also insures your personal belongings and gives cover on the same basis as the fire insurance. So, if your personal belongings are insured against fire on a replacement basis, EQCover will also be on a replacement basis; but if they are insured on a less favourable basis than replacement value, than [then] EQCover will be on the same, basis. The limit of EQCover for personal belongings is the lesser of:

– the amount for which your belongings are insured against fire.

– $20,000.

WHAT IF I NEED MORE COVER?

If you think EQCover is not enough for your property, talk to your insurance company who can give you additional cover.

IS ALL MY PROPERTY COVERED BY EQCOVER?

Most, but not all, of it is. Some of the property not covered is motor vehicles, trailers, boats, swimming pools, fences, jewellery, money, works of art, securities and documents.

EQCover insures only direct damage. It does not, for example, extend to paying for temporary accommodation, as some insurance policies do.

WHAT ABOUT MY SECTION?

There is limited insurance cover on your section, mainly the land around the house, with some cover for the main accessway and underground services. An excess applies to claims on land.

WHAT ABOUT FLATS AND APARTMENTS?

A “dwelling” is any self-contained premises being used as a home. The limit on the amount of EQCover you can have applies to each “dwelling”. So a building can contain more than one dwelling , e. g. an apartment block, or a house with a self-contained granny flat. Each building is eligible for cover up to $100,000 multiplied by the number of dwellings in the building.

Therefore buildings which include more than one dwelling can be insured for more than $100,000. To get full EQCover, you must inform your insurance company of the number of dwellings in your building, otherwise you will only be able to claim up to $100,000, regardless of how many different homes are in the one building.

If you live in a “dwelling” which you don’t own, and you have personal belongings, you can get EQCover on those belongings.

ARE THERE EXCESSES?

Yes. For a claim on a house the excess is 1% of the amount of the claim with a minimum of $200 per dwelling. For belongings, the excess is $200. For land, the excess is 10% of the amount of the claim, with a minimum of $500 per dwelling and a maximum of $5000.

HOW MUCH DOES EQCOVER COST?

The cost is worked out at 5 cents (Plus GST) for every $100 insured. The most you could pay a year including GST is $67.50. This will give you the maximum cover of $100,000, plus $20,000 on personal belongings.

EARTHQUAKE COMMISSION CLAIMS

Steps to follow if property is damaged by earthquake, landslip, volcanic eruption, hydrothermal activity or tsunami, and you have a claim on the Earthquake Commission (EQC).

If possible, take photos before moving anything.

You can make temporary repairs for safety or to prevent further damage or discomfort.

You can get essential services like toilets and water systems repaired immediately but keep everything the repairer replaces (and keep a copy of the bill).

You can clean up spillages or crockery and glass breakages (but don’t throw anything not perishable away yet).

You can dispose of perishables like ruined or spilt food. (List the items as you bury, burn or dump them).

Phone EQC free 0800 652-333 as soon as you can to lodge a claim or get more advice. It is better to do this yourself rather than getting your broker, agent or insurance company to call.

EQC will ask for your idea of the extent of damage and who you are insured with. EQC will tell you whether an assessor will call to help you with your claim or whether you can go ahead with getting repairs done. EQC will follow this up in writing.

You must call EQC within 30 days if you want to claim. Also listen to your local radio station.

Earthquake ’31 Page 11

Long-term burden on businesses

The record of Hawke’s Bay’s 1931 earthquake can still provide a shock.

In today’s terms the value of losses and damage in Napier and Hastings on that fateful February 3 was a staggering $900 million.

And it was the business community in both cities which was forced to bear the brunt of that cost.

The burden hung like a millstone round the necks of retailers for more than 20 years. Its weight finally dragged some to a premature end.

Wally Ireland’s dream of becoming a prosperous retailer was shattered in a few brief moments that day – he had been only 11 days in business as picture framer and art supplier.

The first tremor sent stock hurtling around his Dickens Street store; the second hurled him bodily into the street and, as he lay “paralysed” in the convulsing roadway, Napier’s thriving retail area collapsed, then burnt.

The front section of Harston’s building, which was built to specifications prepared after the disastrous Murchison earthquake, withstood the earthquake but the back section was destroyed.

They had planned to rebuild that section but someone stole the bricks before construction started.

The story of losses both in the earthquake and ensuing fires was repeated throughout the entire city.

Business records became of paramount importance because those firms unable to prove their solvency on the day of the earthquake were debarred from assistance.

The loss of bank records added further complications to the business world and several businessmen, even half a century later, were still adamant that they repaid pre-earthquake mortgages twice.

Unfortunately, the disaster occurred at a time of depression. The government’s grants amounted to about a fifth of the estimated total losses in Napier and Hastings, though it did make some loan concessions in later years.

Although loan moneys, through the Napier Rehabilitation Committee, were made available to businessmen for the re-establishment of the retail area, it was generally not enough.

One borrower, who needed $150,000 to re-build and another $26,000 for stock, received a loan for only $39,000.

It was the support Napier received from the wholesale industry that played an important part in the restoration of the business sector.

Wholesalers and other large business interests in other areas of the country rallied around and while they were not always able to provide monetary aid, they gave help in other forms.

In the first weeks after the earthquake efforts were concentrated on restoring essential services and repairing homes; there was little help for the businessman.

Some optimistically opened in undamaged back-rooms or erected their own temporary premises on their devastated sites. The first tangible sign of a return to normal in retailing came with a $20,000 loan from the government for the building, by the Fletcher Construction Company, of temporary premises in Clive Square.

And on March 16, nearly six weeks after the disaster “Tin Town” was opened with provision for 54 shops.

The actual reconstruction of the business area was delayed while planners widened the three major streets, Tennyson, Emerson and Dickens Streets, and set aside space for service lanes in the business area.

The rebuilding of Napier was the greatest programme of concentrated building New Zealand had seen, and, in the first two years after the earthquake, permits for the construction of new buildings worth nearly $1.6 million were issued.

The first new permanent building to be completed was Barrys Bottling Co Ltd’s Wellesley Road premises, and one of the first businesses re-established in the inner city area was Canning and Loudoun’s Tennyson Street garage.

The Masonic Hotel opened for bar trade in December 1932, and Hector McGregor Ltd was also operating from new premises about the same time.

By January 1933, 108 shops in the new Napier had been completed, 21 were still unoccupied and 43 were under construction.

By 1940, as New Zealand clawed itself out of the depths of the depression and into the grasp of a major world conflict, the rebuilding of Napier was virtually completed.

After being confined to eight streets at the time of the earthquake, Napier’s business centre has now expanded into Raffles and Vautier Streets with office blocks rising in what were once residential areas.

The government may have dragged its feet over financial aid to the province’s commercial interests, but its departments moved much more decisively to restore transport and communication links.

At 1.35am on February 4 the first telegraph communication from Hastings to places south was arranged and 12 hours late Napier was reconnected.

A regular air service started between Auckland, Gisborne, Hastings and Wellington, which carried mail, messages and supplies regularly until February 9.

Postal and telegraph services were also carried by motor vehicle to post offices at Waipawa, Waipukurau and Dannevirke, where they were directed on to their destinations.

Some of the Hastings and Napier staff were transferred to the branch offices to cope with the rush.

Nearly all telegraph communications had been restored to some semblance of normality by February 5, although telegrams into the stricken area were still being accepted at the “sender’s risk”, due to the displacement of so many people.

By February 7, mail services had been resumed from temporary post offices at the Hawke’s Bay Farmers’ Buildings in Napier and the railway station in Hastings.

As soon as it was discovered rail communications were interrupted from Ormondville north, repair gangs were rushed into the district and a train service to Hastings was restored the day after the ‘quake and to Napier the next day.

Although the early trains using the line had to proceed with caution – much of the line had shifted its alignment at various points – the rail service was to prove invaluable for taking refugees to other provinces.

Within a week, damage to the track had been repaired to a standard almost equalling that preceding the ’quake.

To the north, the incomplete Napier-Gisborne railway escaped major damage. Work on the Mohaka viaduct, the largest in the southern hemisphere, had only just started. On the unfinished line some sections were badly twisted, but the main problem was the slumping of embankments. The line was to take until 1939 to reach Wairoa.

It wasn’t until February 16 that a regular Hawke’s Bay Motor Company vehicle negotiated the Napier-Wairoa road, although access had been gained several times during the previous week by one or two adventurous motorists.

At Wairoa the main road bridge across the Wairoa River was badly damaged in the first ’quake. It was completely destroyed by a later ’quake, in September 1932.

The Napier-Taupo road was blocked by slips and was not negotiated for more than a week.

Photo captions –

Sleepers and railway lines go round a brand new bend between Napier and Bay View.

Abandoned vehicles in the fissures that formed in the embankment road linking Westshore with Napier.

Tin Town, the temporary shopping centre built on Napier’s Clive Square.

Earthquake 31 Page 12 Earthquake 31 Page 13

Napier- thriving, destroyed, reborn

Panoramas of central Napier before and after the 1931 earthquake.

This picture was taken in the mid 1920s.

This picture was taken soon after the area’s near total destruction by shaking and fire.

The only four major commercial buildings to survive in central Napier have been numbered and can be seen again in the bottom picture. They are the then new post office (1) and Public Trust Office (4) and the buildings now occupied by Classic Hits 89FM (2) and Hallensteins and Glassons clothing shops (3).

This third picture was taken in 1935, showing truly amazing progress with reconstruction in a mere four years.

Earthquake ’31 Page 14

They lived through the ordeal

Personal experiences of the 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake as recounted to the Daily Telegraph for the pages of a commemorative publication 50 years after the event.

Mr Jack Greatbatch, of Napier, lost his father in the earthquake, and his ill mother died three months later.

Mr Greatbatch was sitting beside Steve Moss in room C2 at the Technical College when the earthquake hit.

“We both went toward the door, but a clump of bricks fell down from the chimney, forcing us back.” he said.

“We went back and hid under our desks, terrified. Steve then broke a window, which I thought was a sacrilege then.

“We saw a ray of sunlight and realised the wall had fallen out, so we scrambled out through the dust and rubble into Station Street.

“We had a few cuts and bruises, but otherwise we were okay. We were all made to go and stand in the ground opposite the Catholic church and when the second big shake came we looked over and saw the church tower shaping toward us, with the bells ringing. I don‘t know how it didn’t come down.

“I then hightailed it home down Munroe Street and a further ’quake opened up wide fissures in the area where the trees are now planted, while one or two of the big water tanks in the railway yards split.”

It was not until later that day that Mr Greatbatch learnt that his father, Tom Greatbatch, had been killed when a wall from Barry Brothers’ Bottling Company building fell on him.

His mother, Lydia Greatbatch, was in Napier Hospital where masonry crashed down all around her but she was unscathed. It took five nurses to lift the masonry off her bed.

Mrs Greatbatch was transferred to Masterton Hospital.

Mr Jack Greatbatch lived in Masterton for the next 2½ years and many of his friends in Napier treated him as a Jonah every time he returned.

“You could just about bet on it,” he said. “Every time I came back there was another earthquake. A woman I used to board with when I came to Napier took it so seriously she immediately took everything off her shelves from the time I arrived.”

Mr Greatbatch recalls another unusual incident at the time of the earthquake. “There was an odd shower of rain that fell over our house in Napier South, yet the rest of the sky was cloudless and it was a bright sunny day.”

Sailors’ grim tasks amid wreckage

There were many acts of bravery in Napier after the quake. Some of the sailors from HMS Diomede earned high praise for their efforts.

One was Jack L Harris, a cousin of Napier shipping company manager Eric Presling.

Mr Harris, who became a resident of Wellington, recalls that he was in a party sent up to the Bluff Hill reservoir, the top of which had collapsed.

“The reservoir was completely drained of water, and we had to clear many tons of broken bricks, mortar, stones and earth by loading it into buckets let down on a rope through the great gaping hole above,” he said.

“We were working between 30 and 40 feet underground, the entrance being down a ladder in a very narrow shaft which could be used by only one person at a time.

“While we were underground another shake took place and the earth was visibly trembling. If the top of the reservoir had caved in, we would not have had a hope of escaping alive.

“That job was completed early afternoon, to our great relief, and we then went to the Masonic Hotel, then a mass of smoke-blackened bricks spread out over the footpath and half way across the road, with several crushed and ruined motor cars underneath.

“Our object was to recover bodies which were known to be there and we came across them after clearing away a lot of debris.

“I have tried to erase that sight from my memory – one of the most revolting it has ever been my misfortune to witness. Those crushed, mangled and burnt corpses with a look of horror and fright on what remained of their faces.

“As they had been dead several days it was far from pleasant to be too close to them. We had to carry gas masks with us. As the bodies were recovered they were placed straight into plain wooden coffins. We saw huge lorries loaded right up with those coffins on their way to the burial ground.”

Mr Harris also recalls that the section he was with cooked and served meals from the old Hastings Street School.

“A majority of old people had congregated there this sunny day barely 24 hours after the tragedy; it was pathetic to see the look of despair on their faces.

“They were virtually helpless to do anything for themselves, still stunned by what they had been through the previous night of horror, as if unable to realise just what had happened, while probably a large number of them had lost very near relatives and friends.

[Advertisement]

ALEXANDER

CONSTRUCTION (HB) LTD

Registered Master Builders

– Residential – Commercial – Industrial

For Buildings that stand up to the test of time

Dunlop Road

Napier.

Phone 843-9626

Fax 843-9079

Registered mb

Master Builder

MEMBER

Earthquake ’31 Page 15

Clerk’s warning saves lives

The actions of Claude Temperton, chief clerk of the New Zealand Insurance office in Napier 50 years ago, saved the lives of several people.

Mr Tom Prebble, who was a 19-year- old clerk working in the NZI building, then sited on the corner of Tennyson and Hastings streets, recalls the events:

“Mr Temperton stopped people rushing out of the building when it was still shaking following the first big earthquake.

“If he hadn’t done this, I am certain several of our staff would have been killed. As it was, one of the girls (a Miss Brandon) who worked upstairs in the solicitor’s office was killed when a piece of masonry fell on her.”

Mr Prebble who worked for NZI for 41 years, retired as manager in Napier in 1971.

“I was just sitting at my desk in the office, which was opposite the Masonic Hotel, when I felt a terrible rumble,” he said.

“I said: ‘That’s a big truck going up the street.’ Then she blew. It was just whoof, whoof. Very few could stand. I had a pole next to me so I grabbed that and I was later told that I said: ‘This is the end of the world.’

“I was also told that I grabbed one of the office girls’ legs and hung on, but I can’t remember that.

“The building was made of large Oamaru stone blocks. It was lined with wood and had wooden floors, but they had limestone filler between the first and second floors to deaden the sound.

“The result was that you could hardly see a thing for dust and rubble.

“Bricks also flew off the parapets of the Masonic Hotel and were hurled across the road through our windows.”

Mr Prebble was one of nine people in the office, including his sister Maisie (later Mrs Ogilvie), and when they left together they walked along Herschell Street.

“We saw a girl lying dead outside the Hawke’s Bay Council building,” he said. “We then came back along the Marine Parade, which was undulating just like a sea.

“The whole front of the Masonic Hotel had fallen out. We saw an amazing rescue. A man was sitting on his bed on the top floor, apparently caught by a beam. The fire brigade put up a ladder to rescue him. The fireman would run up the ladder, but would then run down again as the building was shaking terribly. He did that several times before he eventually freed the man and they both ran down the ladder, one after the other.

“After this our attention was drawn to the sea. It had receded such a long way and this was why there was a fear of a tidal wave coming and people were told to go up the Hill.”

Mr Prebble was one of several men also detailed to go to the hospital and help.

“We got a lift up in a car and when we got there the hospital was a terrible mess,” he said.

He and others assisted by carrying blankets to the first-aid post at the top of the Botanical Gardens. He also remembers seeing rescuers recovering a girl from the bottom of the demolished nurses’ home.

“She had been on night duty and had been trapped. She spent more than four hours there before they got her out.”

The nurse was Miss Tuppy Loten, whose father was the headmaster of Te Aute College. She became Mrs Sam Dwyer, the mother of Jeremy Dwyer, who was to come Mayor of Hastings.

Mr Prebble said about 35 people slept on the lawns outside his parents’ home for several days.

Ten days after the earthquake he and the other NZI staff were sent to Dannevirke, and they worked in the company’s office there for six months.

“Just when we were leaving home there was another quake which was just as big as the first one,” he said. “Our house really shook.

“We eventually got on the train that had come up from Wellington with many men seeking work in the rebuilding of the town, as this was in the midst of the Depression. However, many of these men never got off the train. That shake was enough for them and they went straight back to Wellington.”

Photo caption – TOM PREBBLE

Two-storey college collapses

Late Napier businessman Mr Jim Rogers was a 14-year old-student in Class C1 of the upstairs section at the Technical College on the corner of Station and Munroe streets when the ’quake struck.

Recalling his experiences shortly before he died, he said. “We had just gone back after recess and we were sitting at our desks when the ’quake came. As the whole building was brick, the walls went out and the roof collapsed.

“The only thing that saved us were the desks. No one was killed in our class but we had to crawl out underneath the desks to the passageway and find our way down the stairs.

“You couldn’t see for the dust from the broken mortar. l climbed out over a high concrete wall and then the second shake came. I jumped off the wall and down into Station Street. Then I ran down to Dad’s shop – C E Rogers Ltd.

Later he and his mother were evacuated to Nelson where they stayed with relatives for two weeks.

The family shop and furniture factory was burnt down in the fire that followed the earthquakes, but it was rebuilt on the same site.

[Advertisement]

OUT OF THE EARTHQUAKE CAME ART DECO NAPIER

DISCOVER NAPIER’S TREASURES – TAKE A GUIDED

ART DECO WALK

Walks leave The Art Deco Shop at 2.00pm every Saturday, Sunday & Wednesday, year round. (From 26 December to 31 March, walks are conducted daily). The walks include introductory slide presentation, walk, brochure, video screening and refreshments.

Enquire about Mid-Summer

MORNING WALKS

DISCOVER EXCITING SHOPPING AT THE ART DECO SHOP

Books, postcards, notecards, note-paper, poster & prints, tee shirts, caps, umbrellas, tote bags, tea towels, ceramics, jewellery, giftwraps, spoons, badges, chocolates, videos, embroidery kits. Art Deco Walk & Tour Guides, aprons, CDs, photo frames, scarves, tiles, cocktail glasses & more.

Have a complimentary tea or coffee

WATCH A VIDEO

THE ART DECO SHOP

DESCO CENTRE, 163 TENNYSON STREET (Opp Clive Square)

OPEN DAILY 9.00 TO 5.00pm (shorter hours in Winter)

Earthquake ’31 Page 16

Stunned citizens in rubble-strewn Hastings Street, Napier, watch the daunting task facing firefighters in the hours following the first jolts.

On the fringes of Napier city some houses on the hill collapsed altogether.

The Masonic Hotel ablaze as viewed from the intersection of Hastings and Tennyson streets, Napier.

Dr. Moore’s private hospital on Marine parade snapped at the base and toppled backwards.

[Advertisement]

Are you a Commercial Property Owner or Tenant?

Knight Frank is a specialist commercial and industrial property valuation and advisory services firm that comprises 16 offices throughout New Zealand.

Our Napier-Hastings office is active throughout the Hawke’s Bay and East Coast regions and provides professional commercial real estate research, valuation, advisory, negotiation, arbitration and administration services for the purposes:

Finance and Insurance

Market Rental Determination (Rental Reviews)

Development Decisions

Refurbishment Cost-benefit Studies

Lease and Real Estate Acquisitions and Disposals

Market Trends Analysis

Investment

Contact the experts at:

Knight Frank KF

Knight Frank

Registered Valuers and Property Consultants

Knight Frank House, Cnr Dalton & Station Sts, NAPIER

Tel: (06) 834 0012 Fax: (06) 835 0036

Earthquake ’31 Page 17

Young refugee tells her story

I remember mechanically thinking I must get home to see how the rest of the family had fared, but my legs seemed devoid of power.

I half fell into huge vents in the ground and stumbled over mounds of soil and concrete where banks and gardens had fallen on to the roads.

I think it was my first glimpse of the sea that shocked me most. It had swept out in one vast movement and the sea bed was visible for miles. I think the thought was uppermost in the minds of many people that a tidal wave would follow.

I could see great clouds of smoke billowing from fires which had already broken out in the region of the harbour.

At last I was in the street where I lived and on all the faces of neighbours and friends was the same half incredulous and dazed look as each one tried to think out some sense in their confused minds.

I pushed open the back gate and was immediately confronted with an assortment of bricks from the chimneys, upended water pipes and broken drains, protruding at all angles from vents in the ground. Overhead, electric wires dangled aimlessly where they had been wrenched from the side of the house.

I made my way to the gate again and my mother was coming along the road with my younger sister who had been waiting at the school. Of another sister and brother there was no sign.

We saw a car go past and stop outside our gate. In it was my brother with his head heavily bandaged. He was in the second storey of the Technical College at the time and the whole building collapsed.

We were beginning to wonder if we would see our other sister again when we heard that she had gone up to the Hill because of the rumour of a tidal wave. A friend offered to bring her down from the hill, and soon our family was complete.

We managed to carry a mattress along to a nearby section and made my brother as comfortable as possible. The night seemed endless, and full moon was blood-red from the reflection of the fires. The ground trembled with shocks of varying intensity.

The dawn came and revealed in all its starkness the utter desolation. There was very little to eat so I thought I would go over to the town and try to procure something. lt was a nightmare of a journey, and at one stage the road was completely blocked. I tried a different route and on my way passed the nurses home at the hospital, which had fallen down like a pack of cards killing several night nurses who were asleep at the time. Patients from the collapsed wards and injured people from the town, were taken to the Botanical Gardens nearby where beds were placed beneath trees.

Houses and lamp-posts were tilted at the craziest angles, and from one home a woman ran out screaming. Evidently the strain of further quakes had proved too much for her. A little later l was in the town itself and I could only stand and gaze uncomprehendingly at the ghastly scene. Fires were smouldering in every direction, and weary, smoke-grimed firemen were struggling desperately to stem the shooting flames. Great heaps of blackened masonry thrust gaunt shapes against the grey sky.

I wandered on, and came to an area which so far was free from the flames. Here a butcher had a temporary stand and was serving meat to any who cared to purchase it. I bought some chops and with a few stale buns headed home. I arrived back eventually at our small camping area to find that most of the women and children were preparing to leave the town. The probability of an epidemic through lack of water and the destroyed sewerage system was an ever-present menace.

By this time my brother was in a good deal of pain from the injuries to his head, and needed a doctor’s care. We heard that there was a medical officer on board HMS Veronica, which was aground in the inner Harbour.

While my mother took the rest of the family down to the boat, I went home to see what I could gather in the way of clothes. A large wardrobe had fallen over on the suitcases and l was unable to lift it, so l found a blanket, and placed a few articles in it for each member of the family.

While I was in the midst of it, a heavy jolt shook the house and I dashed outside. When I had plucked up sufficient courage to go in again. I picked up my bundle. By this time I was glad to get out of the topsy turvy house, and having placed the blanket and contents on the seat of my bicycle I wended my way over piles of debris to the wharf.

An hour or two later we heard that we would be able to go to Wellington the following day in the ship Ruapehue [Ruapehu]. The Northumberland, which was anchored in the bay at the time, offered to take as many passengers as she could on board for the night. We left the Veronica in one of her launches.

Later we were told we were to be transferred to the Ruapehue [Ruapehu]. This time by a cargo sling, as the gangway was considered too difficult to negotiate in the choppy seas.

I remembered I had left my bicycle on the wharf before going aboard the Veronica. At any other time this would have been a vital loss.

Several members of the Red Cross were gathered on the Wellington wharf and they helped us into waiting vehicles and we were driven to the Town Hall where women from different organisations provided us with clothing and anything else we required.

Later we were informed that those having no relations to go to would be billeted with different people who had offered to take the refugees. We were driven to a home not far from the city and two rooms were placed at our disposal. These kind people did all they could for us, and we were there for about three weeks.

At last we heard that we could return to Napier. It was a strange home-coming, as we had no idea what to do. We knew our home was unlivable in its present condition, if it had not already been burnt. After making inquiries our mother was told that tents had been erected in one of the parks to enable returning residents to stay there until their own homes were habitable.

The next day my mother and I went home to see if we could do something to it. The house was still there! And some kindly soul had seen me leave my bicycle on the wharf and had wheeled it home, for there it was inside the gate, with two very flat tyres.

Napier resident Rona Lawrence (pictured) was 17 at the time of the earthquake, and wrote this account of it four years later.

At the time of the quake she was visiting a friend on Bluff Hill. Her mother and family lived at Ahuriri. Her father had died in 1927.

She was inspired by her experience to enter a competition in 1950, when Napier was declared a city, to choose a motto for the new civic coat-of-arms. Her entry, “Faith and Courage”, won and became Napier’s’ motto.

Photo captions –

The earthquake caused the complete collapse of the brick-built Anglican cathedral in Napier (left), with the loss of two lives. But as can be seen from the picture of the ruins (right), the parish hall behind it escaped almost unscathed.

Pulling down an insecure wall in Napier’s Herschell Street.

Sailors working through the rubble at the Napier Technical School, where 10 died on their first day back after the summer holidays.

Our 127th year

The Daily Telegraph

Monday October 7, 1997

some things never change…

The Daily Telegraph building before the 1931 Earthquake.

The present building erected after the 1931 Earthquake. Photo taken 1933.

Technological advances and instant communications now enable us to bring national and international news right to your home within hours of happening. But some things never change – The Daily Telegraph’s commitment to bring you a news service six days a week, delivered to your home.

The Daily Telegraph building today.

Earthquake ’31 Page 19

Door opened to expansion

It is surely ironic that the earthquake which virtually demolished Napier in 1931 was a salvation for the town.

For it was the devastating quake, and the fire which followed it, that opened up the way for Napier to progress.

For 80 years before 1931 the town had been hemmed in, its expansion blocked by sea and swamp.

But immediately following the disaster of February 3, 1931, the town’s civic fathers acted to redevelop the town, to re-plan it for the future, to make good new land which nature had forced upon them.

Not only did the disaster give the town much needed space for growth – it also led to new approaches in civic planning, in architecture and in roading, and changed the entire face of the town.

Some have described Napier before the earthquake as dramatic, a town nestled up against Scinde Island with the Pacific Ocean to the east, inland waterways to the west.

But another early assessment, from 1860, described the area then as “a barren, uninhabited, hopeless spot for a town”.

Whichever, the earthquake certainly changed it all. In 1925 Napier could not have grown more without enormous sums of money being spent on reclamation. But with the violent upheaval of 2800 hectares of the lagoon area and the improvement of a further 1100 hectares, Napier‘s future was virtually unlimited. It began to expand in earnest.

A definite town planning process sprang into being. The land famine which had threatened Napier was over.

Engineers diverted the Tutaekuri River, reducing the danger of flooding and opening up a massive new area of safe land for housing and industry.

The Napier Harbour Board, which had a massive land inheritance from the quake, leased 190 hectares to the Napier Borough Council in 1934 which was developed to become Marewa.

Negotiations between the board and council continued over the years to free up more land for housing.

But it wasn’t only new suburbs which grew on the new land.

Over the following decades parks, the airport and the Pandora industrial were all established in places which had once been submerged or at least so swampy as to be useless for development.

The Napier harbour was also completely changed by the earthquake. In 1931 the town had two harbours – the Breakwater and Inner harbours – both separate and both inefficient.

And the earthquake left both in a shambles.

The day after the earthquake it was obvious the Inner Harbour at Ahuriri would be useable only by small ships.

The order went out to the board’s staff to make the Glasgow wharf at the Breakwater and its approaches serviceable.

This was achieved inside a 10-day deadline.

The decision then might be seen as a pointer to the future of port development in Napier. The following years saw a steady and well-planned transition from the two separate harbours to the harbour, in the true sense of the word, which the Port of Napier represents today.

Perhaps the most obvious and inevitable result of the disaster was in the buildings of Napier.

Pre 1931, Napier was endowed with many buildings of interesting design, rich in the detail of the Victorian era. Styles ranged from Gothic revivals and various classic revivals to some early colonial.

But much of this was demolished in the earthquake, in the fire which followed, or in the wave of demolitions of damaged buildings which took place after the quake.

For many years after 1931 the main desire of most citizens was to rebuild and remove all reminders of February 3.

The widespread destruction that day was partly attributable to the inadequate standard of buildings in the town.

Masonry had been favoured as a building material, because of fire problems with timber, but masonry was not earthquake-resistant.

The situation was aggravated because the buildings had been planned by immigrants from lands where earthquakes were little known or understood.

But there were some buildings throughout Hawke’s Bay which survived the earthquake; strengthening systems were developed in the region after the quake, systems which have been employed else where and further developed since.

The 1931 earthquake and consequent fires in Hawke’s Bay emphasised the need for not only up-dating and improving building bylaws but also the enforcement of design standards.

Subsequent earthquakes around the world permitted close studies to be made of building behaviour under different conditions.

The result has been very much higher structural design and fire protection standards being brought into force, not only for new buildings but also for strengthening old buildings as they were refitted or altered.

While the effects of the earthquake and fire of 1931 are evident in the whole of Napier as it is today. there is only one specific memorial to the earthquake.

This is the bell and nameplate of HMS Veronica, which have been placed on Marine Parade.

The Veronica was a sloop attached to the Royal Navy which was in port at the time of the earthquake; her men helped outstandingly in the rescue efforts which followed.

Diagram text –

HAWKE BAY

CITY OF NAPIER 1931

PORT AHURIRI

WESTSHORE

EAST COAST RAILWAY

SOUTH POND

HOSPITAL HILL

INNER HARBOUR (AHURIRI LAGOON)

SWAMP

DAMAGED BUSINESS AREA

NELSON PARK

McLEAN PARK

TUTAEKURI RIVER

BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL

DAMAGED AREAS

EARTHQUAKE AND FIRE

SWAMP

Photo captions –

A view across pre-earthquake Ahuriri Lagoon, from the Poraite [Poraiti] hills to Napier Hill (also known as Scinde Island), with Westshore just visible running off to the left. This area is now airport and farmland.

“…Their sun is gone down while it was yet day.” The memorial grave for earthquake victims in Napier’s Park Island Cemetery.

A 1931 earthquake will happen again somewhere in New Zealand…

are you prepared to survive?

Before

Fasten movable objects

Get a Disaster Survival kit

Make sure you’re adequately insured

During

Keep calm

Stay clear of walls and buildings

Stay indoors

Shelter under tables or door frames

Stay away from glass

After

Turn all energy sources off

Stay indoors until it’s all over

Check for casualties

Look out for neighbours

Listen to your radio

Pick up a free brochure at any Civil Defence office.

For full advice on all disaster precautions contact your local civil defence office at the council offices nearest you…

CD CIVIL DEFENCE

Napier City Council Civil Defence (06) 835-7579

Wairoa District Council Civil Defence (06) 838-7309

Hastings District Council Office of Emergency Management (06) 878-0500

Central Hawke’s Bay District Council Civil Defence (06) 857-8060

Hawke’s Bay Regional Council Emergency Management (06) 835-9200

Earthquake ’31 Page 21

Steps forward in insurance cover

Two massive earthquakes on the North Island east coast were the catalyst which saw the establishment of the Earthquake and War Damage Commission.

The first of the two, the 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake, devastated Napier and Hastings and wrought havoc in Wairoa and Central Hawke’s Bay.

The other, 11 years later struck Wairarapa and also caused disruption in Wellington.

In 1941 the government set up a War Damage Commission and three years later it was changed to include provision for earthquakes.

In 1992 a government and insurance industry working party made sweeping changes to disaster insurance. It began phasing out earthquake cover on commercial buildings and from January 1, 1994 it has introduced cover on residential properties on a replacement value with a cap of $100,000 (plus GST) for home and $20,000 (plus GST) for personal property available for replacement.

The changes mean that people with homes valued at more than $100,000 need to acquire insurance beyond EQ Cover, it they want full protection.

Photo captions –

The tent town set up in Napier’s Nelson Park to shelter the homeless.

Workers and visitors at a Red Cross depot in the grounds of Hastings’ Central School. A staff of 56 manned the depot, which served 2500 hot meals a day and even kept food available throughout the night.

Napier Girls’ High School students sort through salvaged books.

Earthquake ’31 Page 22

A range of other sources

For almost 50 years the most authoritative and keenly sought-after publication dealing with the 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake was Hawke’s Bay Before and After, published by the Daily Telegraph on July 1, 1931.

This volume was reprinted as a facsimile edition towards the end of 1980 with additional chapters by former editor of the Telegraph, Geoff Conly.

Mr Conly, who died in 1992, was also the author of the book on the earthquake, entitled The Shock of ’31, also published in 1980.

H K Stevenson’s history of the Port of Napier, Port and People is also a valuable source of information.

The history of Napier was published by the Napier City Council in 1975 as The Story of Napier, 1874-1974, by Dr M D N Campbell.

Aspects of the earthquake relating to rural Hawke’s Bay are covered in the History of the County of Hawke’s Bay, by Kay Mooney.

Matthew Wright’s book, published by the Napier City Council, Napier City of Style (1996), also contains information on the earthquake and its aftermath.

A detailed study of earthquakes is contained in Earthquakes, by G E Eiby (Heinemann, 1980).

A wealth of detailed information about the earthquake, along with tangible mementoes, is held by the Hawke’s Bay Museum. This includes a wide selection of photographs and many unpublished manuscripts.

A section of the museum has been developed for a permanent display on the earthquake, and it includes a 20-minute audio- visual display.