- Home

- Collections

- JACKSON DL

- Various

- History of Hawke's Bay

History of Hawke’s Bay

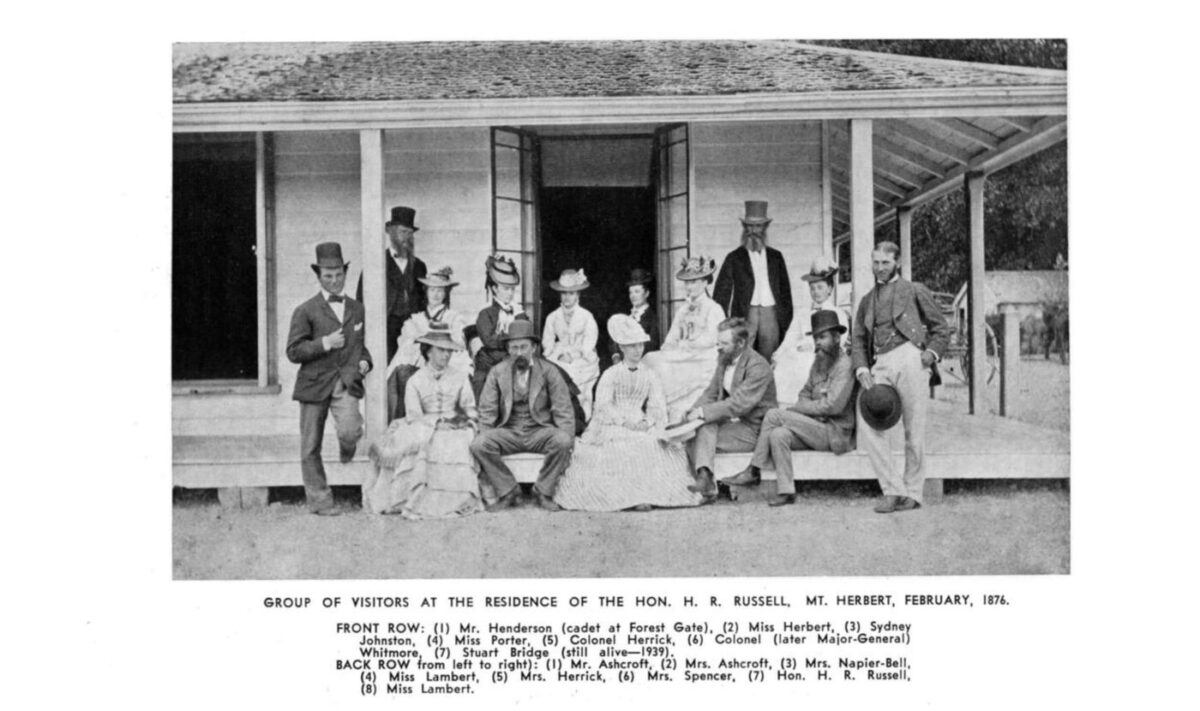

GROUP OF VISITORS AT THE RESIDENCE OF THE HON. H. R. RUSSELL, MT. HERBERT, FEBRUARY, 1876.”

FRONT ROW: (1) Mr. Henderson (cadet at Forest Gate), (2) Miss Herbert, (3) Sydney Johnston, (4) Miss Porter, (5) Colonel Herrick, (6) Colonel (later Major-General) Whitmore, (7) Stuart Bridge (still alive – 1939).

BACK ROW from left to right): (1) Mr. Ashcroft, (3) Mrs. Ashcroft, (3) Mrs. Napier-Bell, (4) Miss Lambert, (5) Mrs. Herrick, (6) Mrs. Spencer, (7) Hon. H. R. Russell, (8) Miss Lambert.

Wholly Set Up and Printed in New Zealand

By Wright and Carman Ltd.,

177 Vivian Street, Wellington,

And Bound by John Dickinson and Co. (N.Z.) Ltd.

Wellington,

For A. H. and A. W. Reed,

Publishers,

33 Jetty Street, Dunedin, and

182 Wakefield Street, Wellington.

London: G. T. Foulis & Co Ltd.,

Australia: S. John Bacon, Melbourne,

1939

FOREWORD.

In this Centennial year it is fitting that we should turn back and look at the past. To Hawke’s Bay the occasion has come as an opportunity to do what had not properly been done before – to produce a comprehensive history of the whole Province.

If this volume has successfully fulfilled that function, it has been due to the unstinted labours and careful research of the members of the Hawke’s Bay Centennial Historical Committee.

This body was formed on 27th October, 1937, at a general meeting, as a Committee of the Hawke’s Bay Provincial Centennial Council, and it was decided that it should produce this history as a Centennial Memorial for all Hawke’s Bay, the various local bodies thereof contributing the required funds.

Thanks are above all due to Mr. J. G. Wilson, whose masterly history, mainly of the early days, was acquired for the use of the Committee, and Mr. W. T. Prentice, who contributed the unique and valuable Maori section. Thanks are due also to Mr. Russell Duncan, for his interesting article on Early Days at the Port of Napier; Mr. C. L. Thomas, for his pretty little piece on Pukemokimoki, the hill of the sweet-scented fern; Mr H. Guthrie-Smith, for his valuable Introduction; Messrs. John Williamson and James Hislop, for the very able and comprehensive Educational section, and the latter for his excellent Military section; Rev. Father Riordon, for his assistance in the Roman Catholic portions of the Ecclesiastical and Educational sections; to Mr. W. T. Chaplin, for his careful checking of the Hastings account; Mr. T. Lambert for his special Centennial history of Wairoa, on

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

which the necessarily brief account given is based; to Mr H. A. Henderson for the use of his thesis on Southern Hawke’s Bay; to the Secretary, Mr A. M. Isdale, for the work of typing and editing, under the supervision of Messrs. Wilson and Price as Co-Editors, and for the article on Settlements on the Puketitiri Road, prepared largely from information supplied by Mrs. F. Hutchinson of Rissington; and especially to Mr. C. Price, to whose indefatigable labours are due the following: – In the Days of the Bullock Waggons, Old Coaching Days, Napier Harbour, Shipwrecks, Napier (except Mrs. Dunlop’s Narrative, contributed by Mr. Wilson), Hastings, Taradale, Sports and a description of the 1931 Earthquake appended to Mr. Wilson’s general article on Earthquakes.

And, furthermore, our most earnest and grateful thanks are due to the unnamed many who have provided materials and assistance towards the shaping of this work.

May it be found worthy of these efforts and of the Province of Hawke’s Bay.

J. A. ASHER,

Chairman.

Napier,

7th September, 1939.

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION 9

PART I – THE MAORI HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

PREFACE 19

I COMING OF TOI. (Rongokako, Kahungunu) 21

II THE INVASION OF HAWKE’S BAY BY THE NGATI-KOHUNGUNU (Turupuru, Taraia’s Raids on Heretaunga) 31

III KAHUTAPERE 47

IV TU AHURIRI 57

V TE WHATUIAPITI 64

VI TE WHEAO PA 73

VII RAIDS AND MIGRATION TO NUKUTURUA (MAHIA) 85

VIII THE LAST FIGHTS IN HAWKE’S BAY 98

PART II – EARLY HAWKE’S BAY.

INTRODUCTION 113

I DISCOVERY OF HAWKE’S BAY 115

II THE DAYS BEFORE ORGANISED SETTLEMENT. (Whalers, Traders, etc. The Explorers and Early Visitors. The Early Missionaries.) 135

Contents – Continued.

Chapter. Page.

III THE COMING OF THE SETTLER. (Origins and Conditions. Maori and Pakeha. Progress of Settlement. In the Days of the Squatter. The First Sheep in Hawke’s Bay, With the Founding of Pourerere Station and Various First Hand Accounts of the Experiences of the Pioneers.) 192

IV TOWNS AND SETTLEMENTS. (The Country Townships. Country Districts and Settlements. Settlements on the Puketitiri Road. Early Residents of Westshore and Petane and the First Township. The Scandinavian Settlements and Woodville.) 264

V ROADS AND COMMUNICATIONS. (By Road and Rail. By Water. By Air. Post and Telegraph.) 324

VI INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL. (Trade. Industries of Hawke’s Bay. Local Taxation in Hawke’s Bay in 1865.) 368

VII GOVERNMENTAL. (Provincial Government. County System.) 380

VIII VARIOUS. (Our Noted Men. Some Stories.) 386

IX TE AUTE COLLEGE AND ESTATE 390

PART III – NAPIER, HASTINGS, WAIROA AND SPECIAL SECTIONS.

I NAPIER AND SUBURBS. (Napier. Taradale and Greenmeadows. Other Suburbs) 407

II HASTINGS 421

III WAIROA 428

IV VARIOUS. Education. Ecclesiastical. Military Section. Napier Musical and Dramatic. Sports. Earthquakes in Hawke’s Bay.) 433

CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY 453

BIBLIOGRAPHY 455

INDEX 458

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

Group of Visitors at Mt. Herbert, 1876 Frontispiece

Relief Map of Hawke’s Bay (1864) Facing Page 16

Map of Port of Napier, 1855 98

Old Pa Posts on Gwavas, near Tikokino 99

Te Hapuku, Paramount Chief of Hawke’s Bay 99

Noah, Native Chief of Pakowhai 99

Rev. William Colenso, First Resident Missionary at Ahuriri 99

Woburn (Hatuma) Outstation, 1860 114

Mr. J. G. Wilson’s Modern Residence – The Author’s Home 114

Hawke’s Bay Coat of Arms 146

Mrs. Roe, nee McKain, Writer of Westshore History 146

Alexander Alexander, First Permanent Trader, 1846 147

Mrs. J. B. McKain and Two Daughters, taken 1875 147

Mount Vernon Homestead, about 1856 162

Forest Gate Homestead, J. R. Duncan, built 1857 162

Bishop William Williams, First Bishop of Waiapu 163

Thomas Lowry, Pioneer Sheepfarmer, arrived 1851 163

C. H. Weber, Civil Engineer, arrived 1860 163

G. T. Fannin, Clerk Provincial Council, 1858-76 163

Sir William Russell’s Homestead, “Tunanui,” 1862 194

Captain Anderson’s Residence, “Omatua,” 1862 194

Sir Donald McLean, Land Purchase Commissioner, etc 195

List of Illustrations – Continued.

Hon. J. D. Ormond, Superintendent Province, 1869-76 Facing Page 195

Mr. Mason Chambers’ Modern Residence, built 1915 210

Waipawamate Stockade, erected in early 60’s 211

Sketch of Omarunui Engagement, 1866 211

Waipawa Town, 1874 274

Hampden (Tikokino) Blockhouse, completed 1865-6 275

Onepoto Military Camp, 1859 290

Tennyson Street, Napier, 1860 290

Gore-Browne Barracks, Napier, taken 1863 291

Deviations on Titiokura Hill, taken 1915 338

Taupo Five Horse Coach, taken 1909 339

G. E. G. Richardson, Shipowner, arrived 1857 354

Inner Harbour, Port Ahuriri, taken in the 80’s 355

Rev. J. A. Asher, Presbyterian Minister St. Paul’s, 36 years, Chairman Hawke’s Bay Centennial Historical Committee 402

Napier Town, 1864 403

Early Napier, date not known 418

Removing Pukemokimoki Hill, 1872 418

Napier, showing Napier South before Reclamation 419

William Marshall, Napier’s First Schoolmaster, began 1855 434

Dr. Thos. Hitchings, Napier’s First Medical Man, arrived about 1856 434

First Buggy in Hawke’s Bay, imported by Father Reignier, taken about 1888 434

Hastings Town, 1886 435

Veterans’ Reunion, 1913 – survivors of 1863 450

Hastings from the Air, 1939 451

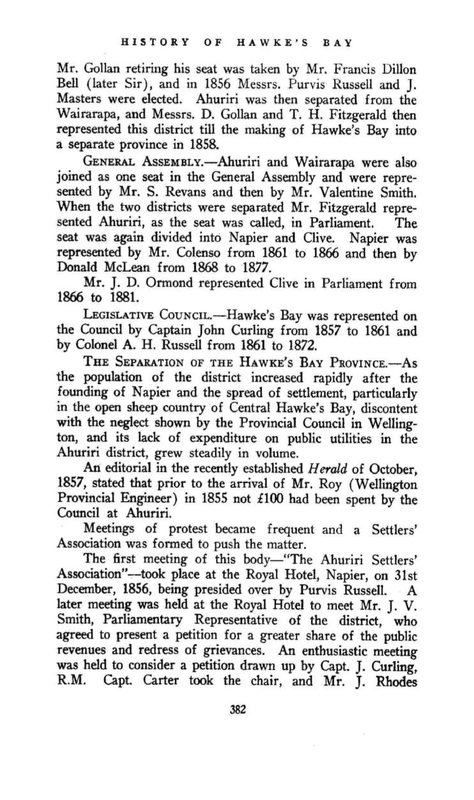

Maps – General Locality; Native Land Purchases; Inner Harbour and Rivers on Heretaunga Plains, 1864, and The Same To-day Inside Front Cover

Genealogical Key to Maori Section Inside Back Cover

Page 9

INTRODUCTION.

CLIMATE: Hawke’s Bay has a Mediterranean climate – warm, dry summers, cool, moist winters – with a tendency to summer droughts and occasional phenomenal cloudbursts of tropical intensity, causing at times severe floods. In 1924, 16 ½ inches of rain fell at Eskdale in nine hours.

BOUNDARIES: The Hawke’s Bay Provincial District is bounded on the north by the 39th parallel; on the west by the watershed of the main range, which passes under various names as noted below, to the Manawatu Gorge; to the south by the Manawatu river to the mouth of the Tiroumea stream, and then in a straight line running eastwards to the mouth of the Waimata creek, on the coast a few miles south of Cape Turnagain.

STRUCTURAL AND SOIL: Hawke’s Bay consists of: (a) Western Range (from south: Ruahines, Kaimanawas, Kawekas and Mangahararus) and its foothills (as Wakararas and Birch Range). Composed largely of grey-wacke, from which our river shingle and possibly gravel conglomerates are derived, this chain ranges from 3,000 to 4,000 feet high. The highest point is about 5,000 feet. (b) Middle Valley, apparently an earth-fold or “structural valley,” which continues the line of the Wairarapa Valley from the Gorge as the Manawatu basin (a hilly basin much broken by deep valleys), the extensive Takapau-Ruataniwha plains (an old lake bed), and the Te Aute valley (divided in two by the Te Aute hill), coming out by Paki Paki to end in the Heretaunga Plains and Hawke Bay. Mainly gravel and silt. (c) Coastal Hills. From the Puketoi Hills a low limestone and papa range with no special name except, behind Havelock North, “Havelock Hills,” goes

Page 10

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

on to end in Cape Kidnappers, and is said to be represented across the bay by the Mahia Peninsula. Its highest point is Kahuranaki (2,117 feet), near the Havelock Hills. (a ii) An extensive area of lower limestone and papa hills running north from Ruataniwha plains between Middle Valley and Western Range; and, from the Heretaunga-Ahuriri plains on, between the Range and the waters of Hawke’s Bay to Mahia. Originally a tilted plateau or peneplain, now cut into gorges and hills and valleys by numerous streams. (b ii) The Heretaunga-Ahuriri Plain, formed by three main rivers (Tuki Tuki, Ngaruroro, Tutaekuri) having filled up a portion of the southern end of Hawke Bay (a process still incomplete when settlement began). These are mainly gravel overlaid with good silt, and are the richest lands in Hawke’s Bay.

It was because of the Western Range that the exploration and early settlement of Hawke’s Bay were so much from the sea and up the coast from the Wairarapa. The Manawatu Gorge was the only gap. The Taupo track was steep and difficult, the Taihape road not completed till the 80’s.

Practically all Hawke’s Bay was at one time covered with wind-blown pumice from the volcanoes on the other side of the range. Erosion has done good service in removing this.

“Havelock Hills” – Actually Kohinurakau Range; other little coastal “ranges” are”- Waewaepa, Whangai, Tutiri and Kaokaoroa.

THE MAIN RIVERS, taken regionally, are: – (a) Northern – The Wairoa, the Mohaka and the Esk flow from the Western Range through the lower hills into Hawke Bay. (b) Central – the Tutaekuri (once called Miani), Ngaruroro (Alma), Tuki Tuki (Plassey) flow into Hawke Bay across the Heretaunga-Ahuriri Plains; the first two from the Kaweka and Kaimanawa Ranges through the lower hills; the last from the Ruahines across the Takapau-Ruataniwha Plains, and thence, passing the entrance to the Te Aute Valley (into which a tributary which joins it just a little further on, the Waipawa, used to flood), it follows a course of its own inside the coastal hills till it swings round to break through the Havelock Hills into the plains. (c) Southern – The Manawatu flows from the Ruahines down the Middle Valley at the southern end of Hawke’s Bay and breaks through the Western Range in the Manawatu Gorge, and thence through the Palmerston North district into the Tasman Sea.

Several short streams, as the Porangahau, run from the coastal hills to the sea.

Page 11

INTRODUCTION

LAKES: (a) Hatuma lake, possibly formed by the damming effect of the flood-plain of the Tuki Tuki across the exit of a wide valley. (b) The old prehistoric Lake Ruataniwha, now as noted elsewhere a large plain, since the breaking through or perhaps earthquake fracture of the eastern hill ramparts in two places to let out the Tuki Tuki and Waipawa rivers. (c) The old (till post settlement) Lake Roto-a-tara, in the southern division of the Te Aute Valley, drained in 1888 by Rev. Samuel Williams. (d) Poukawa Lake – or swamp plus lakelet – in the northern part of the same valley. (e) The beautiful Lake Tutira, apparently due to earth subsidences.

There are also a number of small lakes or large ponds, as Oingo, near Fernhill and Puketapu, which can best be described as “squeeze” lakes, being due to minor earth fold activity.

Lake Waikaremoana is outside the old provincial boundaries of Hawke’s Bay.

VEGETATATION: Pre-Settlement. (a) Western Range and foothills. Bush (not heavy, but beech (miscalled birch) (on all the higher country) and subalpine scrub. The high Inland Patea plateau among the mountains is covered with snowgrass and tussock and small scrubby plants. (b) Middle Valley. With its abundant rain and good soil, the southern part was filled by the 40 Mile Bush (70 or 90, including Wairarapa), all heavy timber, except for natural or Maori clearings – perhaps old lakebeds – as Oringi, etc. It was because of this bush obstacle that the first sheep came up the coast instead of through the Wairarapa and up the Middle Valley, and why in the early stages of exploration and settlement the Manawatu Gorge was not more used. Whether by reason of its more gravelly soil, less rain, or Maori fires, the Takapau-Ruataniwha Plains (save for isolated clumps of kahikatea (white pine), were bare of bush when the whites came, being for the most part (swampy portions and fern areas excepted) wavy plains of high blue grass (agropyrum multiflorum), very nutritious for stock. There were bush areas towards the foothills and by Waipukurau. Te Aute valley was lake, and raupo and flax and toi toi swamp and beautiful heavy bush. (c) The coastal hills were large covered with bracken fern and tutu scrub, except for the highest south and east slopes, where there was bush here and there. (a ii) The “lower hills” were also

Page 12

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

covered with enormous areas of tutu and fern, with 10 to 15 per cent. light bush in the damper portions and a small amount of heavy bush. There was most bush towards the ranges, and as at Tutira, there is a possibility that much lower bush may have disappeared in Maori conflagrations, inevitable where man uses fire. (b ii) On the Heretaunga-Ahuriri Plains were two main patches of bush, the Big Bush and Little Bush. Like the Poverty Bay Flats, their original covering was Microlena Stipoides, often called rice grass, which was good for stock, and considerable areas of manuka (according to Sir William Russell). As it is a fire weed, this must have been due to burning of fern by Maoris. Raupo, flax, toi toi, nigger-head (upoko tangata), cutty grass, etc., were to be found in the extensive swamps.

FAUNA: PRE-SETTLEMENT. With the forests and other varieties of native flora to which different kinds were adapted, native birds were in myriads. Wood pigeons were plentiful, parrots and parakeets swarmed at times in the 40 Mile Bush. There were hundreds of pukeko, tuis were abundant, and bell birds also well known.

Kiwis, not being prolific, were never thick, and the huia had a limited range, in the 40 Mile Bush, being heard at Dannevirke, Woodville, etc.

The strange piping note and whirr of the evening home-ward mutton birds flying overhead in the dusk unseen was very familiar to the early settlers.

The blue wattled native crow, saddleback, and New Zealand bush robin, now gone, were then known.

The long-tailed bat, but not the native frog, used to be quite common in Hawke’s Bay. Lizards were numerous, and there was an exuberance of native insect life: swarms of green and brown beetles and of hole-dwelling native bees (with their natural foe, the tiger beetle), numbers of trap-door spiders and the pretty bright green and vari-coloured hunting spiders (with their enemy, the clay-building mason wasp), and thousands of tiny native butterflies.

PLANTS AND ANIMALS INTRODUCED BY THE NATIVES AND CHANGES: The Maoris brought and cultivated their kumera and taro and yam, making their clearings, and, by accident or design, burning large areas of forest land, which then went to fern, this having happened on a sufficiently striking scale near

Page 13

INTRODUCTION

Tutira. However, the general balance was left very much as it was.

The kiore, or native rat, soon established his little run-aways through the undergrowth, but was not a menace to the birds, and the native dog lived spiritlessly and inoffensively with his masters, content to grow fat.

With the coming of the missionaries the Maori, with new seeds (peach, tobacco, thyme, mint, wheat, maize, etc.) and implements, greatly extended his cultivations, but early in the thirties exchanged various breeds or mongrel nondescripts from traders or whalers for his now extinct dog.

POST SETTLEMENT CHANGES: (a) Clearing. The more open flat country was stocked first, the native blue grass or rice grass being eaten out and replaced by sowings of English grasses. Fern hillsides were burnt and the young shoots eaten and crushed by stock, while the young grass sown took hold – or more often manuka at first in the poorer country. The requirements of building, fencing, etc., began to use small areas of bush, and sawmills were established, as at the Big Bush and Little Bush on the Heretaunga Plains and areas about Waipawa, Waipukurau and Hampden. A big forest still stretched from Waipawa to Waipukurau in 1874. (See map.) This we might call the era of use.

Then came the era of the axe. In 1872, Scandinavian immigrants were brought expressly to clear the great 40 Mile Bush, cutting and then burning to win growing patches from the “wilderness,” while sawmills worked steadily. Fires in standing bush became more and more important, and from the later 80’s to the 1900’s we might call the era of fire, including the great Norsewood fire of 1888, which destroyed part of the village, and the first of the early 1900’s, which destroyed much of the forest towards and in the Wairarapa.

The results have been so often pointed out that we shall only note in passing the great increase of erosion and loss of soil, and remark on the shallowing and shingling of the rivers. This was due in part to greater erosion, in part to the destruction of the native vegetation which had canalised the rivers, trapping the silt of floods and growing thereon, keeping the streams to deep, straight courses. This explains such references as having to cross the Waimarama by canoe, and the canoe and raft transport of heavy goods to Waipawa and

Page 14

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

Waipukurau. Ships at Hadley “wharf” as drawn on plan was then not such a far flight of fancy.

(b) Sowing (and weeds). The richer plains and hills of Hawke’s Bay are now in English grasses and clovers, and everywhere are exotic trees, singly or in shelter belts and plantations. The poorer country has in some cases, after the land has been consolidated by stock, found native grasses “take” where English grasses would not. In others, where occupiers have been less wise or fortunate, burns have brought manuka in place of fern, meaning much toil. Only in the mountains does any great amount of bush – and that mostly light – yet survive.

Of weeds, suffice to note that blackberry has gained a fatal hold on some areas – early brought by missionaries (Jas. Hamlin at Wairoa), it is alleged, like sweet briar (attributed to Father Reignier), also common, but not dangerous. Watercress, whose introduction we have noted elsewhere, makes a welcome addition to our streams, and it would be interesting to know how and by whom mushrooms were introduced. While forest plants, like forest living birds, have suffered most severely from clearing, the imported weeds, far from being able to step in and take their place, have had to compete with the open country native weeds (like fern and manuka) and grasses, which they supplement rather than supplant.

Maori cultivation was important to the early settlers, who used to buy wheat, maize, potatoes, vegetables and seasonal fruits, while export of these also went on from Hawke’s Bay. Having to be self-supporting, the settlers themselves soon grew wheat and ran mills, but with the loss of first fertility agriculture declined during the 60’s and 70’s, and Hawke’s Bay became predominantly pastoral. With the turn of the century, however, dairying in southern Hawke’s Bay, and then fruit growing, market gardening, etc., on the Heretaunga Plains and elsewhere, became established.

(c) The destruction of native fauna – as much by loss of food and natural habitat, consequent on clearing, as by hunting and vermin – meant the disappearance from Hawke’s Bay of native crow, saddleback and bush robin, the extermination of the huia, the decimation of the parrots and parakeets and pigeons, the practical disappearance of the bell bird. With flowering honey-trees round the towns, the tui is maintaining

Page 15

INTRODUCTION

himself and even increasing. The ducks are a remnant, the mutton birds few. The pukeko multiplies again under protection. Some species maintain themselves in small numbers in wooded recesses, others are unaffected or increase, suiting a more open life.

The brown and green beetles and native insects and butterflies are rarer; the old luxuriance has gone. The reason for their decline is partly loss of food and habitat, partly depredations of important and native birds (better able to see them under more open conditions).

(d) Introduction of European fauna. Captain Cook’s pigs multiplied and made their steep tracks; his black English rats soon began to drive to the wall the kiore, to be driven mountainwards themselves by the brown rat of the whalers, who brought also mice. The first horses (Apatu, 1834 and Colenso, 1844) and cattle (Colenso, 1844) are noted elsewhere. In the later forties the Maoris began to bring numbers of horses from Rotorua over their difficult and dangerous Taupo track. With the coming of the settler his horses and cattle, and, above all, the ever-increasing flocks of sheep, beginning in Hawke’s Bay about 1849, began to track and consolidate the land – very spongy in the early days. The run-off – down their tracks – became quicker, and erosion more pronounced. A better consistency was made for grass, both imported and the native danthonia, which was before mainly confined to the hard-beaten areas round Maori pas.

The next noteworthy event is the tremendous increase of the many uninvited insects that came with the animals and seeds. By the 70’s the situation was serious – armies of caterpillars, grasshopper and locust plagues (c.p. Mount Vernon reference), and myriads of other bugs and beasties, devoured all before them. The Hawke’s Bay Acclimatisation Society did as others were doing and imported birds, while mass bird migrations from other districts into the new territory of Hawke’s Bay were a feature of the 80’s.

In the 80’s and early 90’s there were great rabbit migrations – desperately fought by a southern boundary fence about 1883 in the same manner as sheep scab in the 60’s – followed by a wave of weasels. Rabbit Boards sprang up, with regulations, fences and hunters, and the nuisance gradually abated.

Page 16

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY.

(e) Drainage. Early Hawke’s Bay was covered with swamps. The work of drainage done to these was enormous. The real draining of the hillsides, spongy and boggy with the accumulated humus of ages, was done by sheep, with the trading and consolidation and hard water-channel tracks.

(f) Reclamation. Rev. Samuel Williams boldly reclaimed lake and all, with much swamp, at Lake Roto-a-tara. The Heretaunga-Ahuriri Plains had huge swamp and lagoon areas, systematically reclaimed. Nelson and Kennedy’s reclamation of Napier South (completed 1908) as noted, hastened the natural process by copying it, banking off areas into which the river was allowed to pour its silt. The Inner Harbour reclamation was not by man, but by Earthquake (1931).

(g) Rivers control: is a specific problem in the Esk Valley and the Heretaunga Plain, built up by three rivers, all subject to excessive flooding in the occasional violent rainstorms, allied with other factors such as melting snow, high tides and contrary seas, already saturated ground, etc. These floods have on occasion covered large parts of the plain and done serious damage. Forest destruction does not seem to be the main factor, as the first big floods, noted by Colenso, were in 1845 and 1847. The next in 1867, changed the course of the Ngaruroro, the Karamu being the old course, and flooded much of present Hastings. The ’93 inundated Clive, the famed ’97 covered 60 out of 100 square miles of the plain, and ten rescuers were drowned trying to reach Clive. The 1902, 1910 and 1916 floods on the plains, and the 1924 and 1939 cloud-bursts in the Esk valley are the most noteworthy since.

Little has been done to the Esk, but in the Heretaunga Plain successive Rivers Boards, beginning on a district basis, and amalgamated into one in 1910, have wrestled, by means of banking and diversions, with a problem made ever more urgent by increase of settlement and accompanying growth of fences, trees, etc. – barriers to free escape of flood waters.

(h) Earthquakes. The 1931 Earthquake raised the old Inner Harbour, as we have noted. It also loosened the inland country and made it much more liable to slips in wet weather, hastening erosion. The coastline north of Napier was raised considerably. A brief lake was formed in a huge landslide. Past earthquakes, in the light of recent experience, may have had more to do with land formation than was suspected.

Page 19

PREFACE

A writer in these days who attempts to write Maori history requires a great deal of courage, for he has a very difficult task. The Maori had no system of writing by which events could be recorded, and one has to take on chance the history as handed down from generation to generation. The day of the tohunga, who committed to memory many of these things, has long passed, as has the old Maori who had some knowledge of them. The sources of first-hand information are therefore almost extinct. The present-day Maori does not seem to interest himself in these matters, and it is surprising how ignorant he is of the history of his own people and country. It is, therefore, with some diffidence that I attempt this History of the Maori of the Hawke’s Bay district. No continuous history of this district has yet been written, though many of the events that are recorded herein have been touched upon by different writers. I have not hesitated to use the writings of such well known men as Elsdon Best, Sir Percy Smith, J. A. Wilson, Harry Stowell and others, and have also had access to the old Native Land Court records of the late Captain Blake, kept by Mr. J. T. Blake, of Hastings. As a quarter-caste and a Licensed Interpreter, I have had a close intercourse with the Maori people of this district for the last sixty years and also some forty years’ experience in Native Land Court work. I have always interested myself in anything pertaining to the Maori. Much of the information herein recorded is from the knowledge thus gained. It has been difficult to sift some of the matters to obtain the correct version because some of the old men in relating events would, when approached years later, tell a slightly different story. Indeed on two occasions to my knowledge, when works of well

Page 20

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

known writers were produced in the Native Land Court by litigants in support of their claims, such works were refused to be taken in evidence by the Judge on account of the inaccuracy lies therein. It is known that certain battles fought and claimed by the tribes in this district as victories were, by the other side, claimed as defeats. It is with the Maori as it is with other Nations. Take, for instance, the reports of the Ethiopian, the Sino-Japanese, and the Spanish wars where cables one day told of battles fought and victories won which were contradicted the next day by the other side.

Though I believe the events herein recorded are in the main correct, I fully realize that there may be other versions which some may prefer to accept.

The Maori is a highly imaginative fellow, full of worship of his ancestors, often claiming them as super-beings and clothing them with supernatural powers. Who, for instance, can believe the story of Maui fishing up New Zealand from the bottom of the sea with, some say, the jawbone of his grandfather, others, the jawbone of his ancestress, and others, his own jawbone that he had taken out? Again, who can believe there ever existed a giant of the magnitude of Rongokako, who when smoked out of his cave, took one step from Kidnappers over to the Mahia peninsula, another step to Whangara and then jumped over the trap laid for him by Tawa into the Bay of Plenty? The reading of Maori history has a charm of its own, but the reader is left to sift the fact from the myth, the natural from the supernatural.

A whakapapa, or genealogical tree, of some of the leading local families of Heretaunga is attached hereto and goes right back to the first Maori, Toi Kairakau or Te Huatahi. A reference thereto will enable one to fix fairly closely the period of many of the events herein recorded. The general method adopted in these matters is to count a generation as 25 years.

This little work has been undertaken at the instigation of, and as an assignment from, the Hawke’s Bay Centennial Historical Committee, and I hope it will afford some pleasure and interest to its readers.

W. T. PRENTICE.

5 Madeira Steps,

Napier.

Page 21

CHAPTER I.

COMING OF TOI.

It is generally known from various native sources that the first Maori to come to this district was Tara. To know who Tara was it will be necessary to go back to the Polynesian ancestors of the Maori. It is said that during a regatta held about seven hundred and fifty years ago at Tahiti, the contestants in the large canoe race went out of the lagoon beyond the reefs into the open sea. A terrific gale, accompanied by fog, suddenly sprang up from off the shore and drove the canoes far away from home, and some of them were cast upon different Islands. One of the anxious ones on the home Island was an elderly man called Toi, whose grandson, Whatonga, was one of the missing contestants. After waiting many days in vain for Whatonga to return Toi equipped and manned his large canoe, which he named “Te Paepae ki Rarotonga,” and went in search of his beloved grandson. Failing to find him amongst various islands, as a last resort he remembered the land of Aotearoa that Kupe had found and sailed thither, calling at the Chatham Islands on his way. After many days he reached Aotearoa, landing in the North Island in the vicinity of Auckland. Gaining no information here of his grandson, he soon put to sea again. Sailing down the coast to the Bay of Plenty he landed at Whakatane. This was destined to be his last sea voyage, for this old sea dog and intrepid sailor decided to remain there permanently. Here he built and ensconced himself and party in a strong, terraced pa known as Kapu-te-rangi.

To return to Whatonga, it appears that he and his comrades were cast upon one of the islands in the Society group,

Page 22

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

and, in the course of time, when opportunity offered, they eventually returned to Tahiti. Whatonga, finding that his grandfather had not yet returned from his quest, decided to go in search of the old man. After equipping and manning a large canoe, which he called the Kurahaupo, Whatonga and his friends set sail. A search among the various islands failed to find his grandfather, and this bold young sailor decided to sail to Aotearoa, which he reached in due course. He found, after enquiring at several places, that Toi had reached Aotearoa and was living at Whakatane. Thither he turned his canoe, and in due course, landed and found his grandfather.

Later on Whatonga decided to strike out for himself, so sailed down the coast and landed at Nukutaurua at Mahia, where he settled permanently. Here he and his people held sway right up to the Wairoa district. Years later, Whatonga’s two sons, Tara and Tautoki, decided to set out for themselves and, manning their canoe, set sail for Ahuriri.

Now it must not be thought that these two were the first settlers in this district. When Toi and his people came to Aotearoa it was found that the place was already inhabited by people organized into tribes. The accounts are somewhat confused; these aboriginals are sometimes called the Maui people, the Maruiwi, the Moriori, etc. Hawke’s Bay, with its Inner Harbour abounding with all kinds of fish, and its beds of shell fish, and its rivers, lakes and swamps teeming with eels and all kinds of game, was a veritable land of plenty, and had naturally attracted settlers. Tradition tells that at Maori Gully, near Te Pohue, a large section of the Maruiwi had met disaster. At night, with the enemy in full chase, and ignorant of the track, they fell over one by one into a deep chasm and were killed. This disaster was known as “Te Heke-o-Maruiwi.” There were also men who claimed descent from the Marangaranga people, while at Porangahau there were tribes known as the Raemoiri and Upokoiri. Very little, however, is known of these people. They were not of the calibre of the Toi people, and in warfare many soon succumbed to the more virile Polynesians, while others became absorbed by intermarriage.

At the time Tara and his brother came the outlet of Te Whanganui-o-Rotu, otherwise known as the Ahuriri Lagoon,

Page 23

COMING OF TOI

was near Petane. Although long since filled up, traces of this outlet still remain. Driving his canoe up this channel and running it ashore, Tara was the first to jump out. Immediately on touching soil he heard his putorino, or bugle, being sounded far away at Wairoa, which caused him to emit a prolonged Ketekete – a noise made by clicking the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth, as when urging on a horse or expressing surprise. That incident gave to the spot its name of “Keteketerau” (a hundred surprises), by which it is known to the present day. The brothers soon found out what a land of plenty they had come to, with food all round ready for the taking. Later on they went inland and lived awhile at Heretaunga. It was not long before Tara discovered the three lakes known as Poukawa, Roto-a-Kiwa and Roto-a-Tara, the last being named after him. These lakes abounded in all kinds of waterfowl, also in tuna, kokopu, inanga and fresh water pipi. Here was food in plenty. Tara, being a greedy man, reserved these lakes for himself. He was looked upon as a sacred man, and his people were therefore careful not to touch the products of the lakes, which he so reserved. The small, central lake on the top of the hill, Roto-a-Kiwa, was set aside by Tara as his bathing pool. In their season were caught and brought to Tara the fowl and fish from the lakes. In the Roto-a-Tara there is a small island called “Awarua-o-Porirua,” in connection with which there is a certain Maori legend. It is said that while Tara lived here there existed at Porirua a certain taniwha named Awarua-o-Porirua. It is strange that no Maori can tell us what a taniwha is like. Apparently it is a mythical amphibious monster, mentioned by the natives of the Pacific in their legends of the far homeland, that bores under water deep into the ground. This taniwha left Porirua with another taniwha and travelled northwards, killing and eating people as they came. The aboriginals of the Porangahau district, the Raemoiri or Upokoiri (people of the overhanging brows, or suspended head), became very much alarmed at their approach. They made a stout resistance and fought the invaders. One of the taniwhas was killed, but Awarua-o-Porirua managed to escape to Roto-a-Tara. There he found a home with plenty to eat, and he bored for himself a hole in the lake. Tara, hearing of the arrival of this taniwha at the

24

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

lake and the encroachment on his preserves, became very angry and he made his way down to the lake to fight the invader. In the fierce struggle that ensued the taniwha was defeated, and managed to make its escape to Porirua. During the fight the lashing of the monster’s tail stirred up the sand in the bottom of the lake and this formed a sandbank above his burrow, which eventually became an island known ever since as Awarua-o-Porirua.

Tara and his brother did not reside permanently here. They wandered southwards to Wairarapa and to Wellington. The Wellington Harbour was in time called Te Whanganui-a-Tara, so it can be said that they held sway from Ahuriri right through to Wellington. They prospered in the land and their families grew, and their descendants became known as the Ngai-Tara and the Rangitane. The Rangitane were so named after Rangitane, Tara’s nephew. The Ngati-Upokoiri eventually came to Roto-a-Tara and built for themselves a strong pa on the Island. Here they dwelt for some generations and, though the place was attractive on account of its abundance of food, the Ngati-Upokoiri do not appear to have been ousted in the various skirmishes that were fought on the shores of the lake until some generations later, when the Ngatikahungunu came to the district.

Before going further it will be necessary to give the table of descent of some of the leading parties: –

Toi-Kairakau

Rongoueroa

Awanui-a-Rangi

Hingunui-a-Rangi

Rauru

Rere

Tata

Tato

RONGOKAKO

TAMATEA

KAHUNGUNU

Page 25

COMING OF TOI

RONGOKAKO.

There were giants in Aotearoa in the early days. Some five hundred and seventy-five years ago there was one known by the name of Pawa, who held sway in the Bay of Plenty. He kept to his own district, where he held great mana. Another giant was Rongokako. He was born in Aotearoa and was a Maori. There is a small mountain called Kahuranaki, about half-way between Hastings and Waimarama. It stands two thousand, one hundred and seventeen feet above sea-level. This, to the Maoris, is a sacred mountain, and from the shapes of the mist on its summit they can forecast the weather. When the late chief Te Hapuku lay a-dying he asked that he be placed so that his eyes would close resting on Kahuranaki. In a cave in this Mount lived Rongokako. Kahuranaki was then the gateway between two populous districts, Heretaunga and Waimarama. In those days people had to walk between these two places and they had to pass by the Mount. Now the giant Rongokako was very fond of human flesh, and as long as he could get that he would eat nothing else, so he spent a good deal of his time looking for it. He lay in wait on the track and when any traveller passed that way he cracked him on the head with his long club and took him off to his cave.

Soon the people of Waimarama began to miss their folk and asked the people of Heretaunga whether they had seen them, and likewise the people of Heretaunga asked the Waimarama people whether they had seen their relations who had gone thither from time to time. When it was found that neither had seen the relatives of the other suspicion was aroused. A meeting was called, and it was arranged that two small parties should be sent over the track; one to go ahead and the other to follow soon after, keeping the first in sight, but concealing themselves. This was done. All went well until Kahuranaki was reached. Then the second party suddenly saw the giant jump up with his long club and kill the members of the first. They returned at once and reported what had happened, and the people determined to kill the giant. A large number of men assembled and journeyed to Kahuranaki to slay him. They found his cave and he was in it asleep. They

Page 26

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

cut down the bush surrounding the cave, set it on fire and smoked him out. The giant, awakened by the stifling smoke and heat, rushed out of his cave only to find he was surrounded with fire. He saw that unless he got out very soon he would perish. Taking one great leap out of this ring of fire he landed at Te Matau-a-Maui (Kidnappers). From there he took a step right over the bay on to the Mahia peninsula and thus escaped the threatened vengeance.

Now it happened that Pawa, the giant at the Bay of Plenty, knew that Rongokako was coming, so he determined to set a trap and destroy him. This trap or tawhiti was laid between a place called Tawhiti right across to Mount Hikurangi, near the East Coast. Hikurangi is the mountain on which Maui’s canoe is said to have rested after he fished up the North Island, and on this mount Pawa fastened the other end of his trap. The next step Rongokako took landed him at Whangara, just above Gisborne. Looking north, he saw the trap that was laid for him, so he gave one tremendous leap over the trap, but, misjudging the distance, landed in the sea in the Bay of Plenty. Here he had the misfortune to be attacked and pierced by a huge sting-ray, which caused his death.

KAHUNGUNU.

The Maori is ancestor-proud and generally tries to trace his ancestry through one or more of the canoes of the Great Migration in about 1350. As far as the Ngati-Kahungunu are concerned this cannot be done. Kahungunu is the eleventh Rangatira in the direct line from Toi, who came to Aotearoa some two hundred years previously. Intermarriage took place between the two sets of people and they became merged. The descendants of this man inhabit the part of the North Island stretching from the Mahia through Hawke’s Bay, down to Wairarapa and on to Wellington. There are also some in the Bay of Islands, Bay of Plenty and on the East Coast. They are cousins of the Ngati-Porou of the East Coast and of the Ngai-tahu of the South Island. A short history of their progenitor will not be out of place.

Page 27

COMING OF TOI

Kahungunu was born at Kaitaia, in the Bay of Islands. His mother was Te Kura and his father Tamatea, both of high and illustrious lineage. They lived amongst the restless Ngati-Awa tribe, which at that time had settled in the north, and which was later expelled by the local tribes. His father, Tamatea, had built a large canoe named Takitimu, often confused with the migration canoe of the same name. He was one of the greatest navigators of his day. Taking Kahu with him he accomplished the feat of sailing right round the Islands. For this he was called “Tamatea pokei Whenua” (the circumnavigator of the land). Kahu developed into a very industrious and intelligent young man. Tall, peaceable, amiable, he took no part in battles. While still a young man he undertook many successful enterprises both on sea and land. He married his cousin Hinetapu, by whom he had three children. He became involved in the quarrels of the Ngati-Awa, and at their request undertook and engineered the making of a large canal from Port Awanui to Kaitaia to facilitate the passage of war-canoes from the sea. In this undertaking, he was harassed by the tribes that were expelling the Ngati-Awa and was compelled to abandon his operations. Leaving his wife and children at home he went south with some companions and eventually reached Tauranga. Here he had a happy reunion with his father Tamatea and his people. This was the first time he had seen his father since he had left him as a child. Owing to a quarrel over the braiding of a woman’s hair in some fishing-nets Tamatea left the place, and later on Kahu followed him to the Wharepatiri pa.

After a while father and son set out on their travels in a canoe and came to Turanga, now Gisborne. From here they continued southward and came to Arapawanui, in Hawke’s Bay. This was always a prominent landing-place and pa, and noted for its shell-fish, fine fern-root and native rats. From here they came south through the Keteketerau channel on to Roro-o-Kuri, an island in the Inner Harbour, and stayed in the Otiere pa. This was one of the two pas on the island which were later sacked by the Chief Te Koau Pari.

Page 28

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

Father and son enjoyed their stay at this pa and fed on the luscious patiki or flounder for which the Inner Harbour was noted. They even stopped for a while on Tapu-te-ranga, a conical island in the Inner Harbour known as the Watchman, and had as pets a tuatara lizard and a huge crayfish. From here they went inland to Ohiti at Omahu, where the tuatara lizard was lost for a while. When it was found they decided to take it home to the mountain range. Thither they proceeded and took the crayfish with them and came to Puna-awatea, where they placed the crayfish in a large hole in the stream, and at Pohokura, on the Ruahine Ranges, they freed the lizard in a large cave. A greenstone heitiki was fastened round its neck and a tree which was called pohokura was planted. It is said the lizard is still there, and when it roars it is an indication of bad weather. At the Rock Cave, Turangakira, one of the party died from exposure to frost and snow.

The party then left, and by various stages reached the place now known as Whanganui. The present settlement of Putiki derived its name of Putiki Wharanui a Tamatea Pokai Whenua from Tamatea’s top knot. Here Kahu, becoming angry over his father’s greed in connection with a papahuahua, left him.

Tamatea proceeded up the Whanganui River and eventually crossed Taupo Lake to its outlet, where he landed. Through the earth sounding hollow under his feet he called the place Tapuaeharuru (sounding footsteps). Being a great navigator, he boasted to the people that he could descend the Waikato River in his canoe, the Uapiko. Unheeding the warnings of the dangers of the river, he advanced in his canoe until he came to the Huka Falls, where his friend Ririwai left him by jumping ashore. Tamatea and his thirty companions continued on over the falls and there perished. It is said that his canoe, in the form of a rock, can still be seen at that place.

Kahungunu, after the separation from his father, turned his face towards Tauranga. After a long journey by various stages over the Kaingaroa plains he at last got back to Tauranga, his starting place. Here he did not remain long, for he left after being struck in the face with a kahawai by his brother. He travelled through the bush until he came to a

Page 29

COMING OF TOI

cave, which he entered. Here he was seen by a passing native named Paroa, who invited him to the village. He lived at the village for a while and Paroa soon found how capable a man he was, so gave his daughter Hinepuariari to him for a wife.

He soon became restless, and we next find him wending his way along the coast to Whakatane. He was warmly welcomed wherever he went as the Tauranga district was occupied by his own people descended from Toi, their common ancestor, and at Whakatane he was hospitably received by the kindred of his grandfather Rongokako. At this place he took unto himself another wife. It was not long before these people, too, became aware of his industry and ability. He entered fully into their social life and helped to put the place into good order. His reputation grew; so much that parents began to extol him as an example to their young people.

Kahu does not appear to have made this place his permanent abode, for presently he moved on to Opotiki. Here he took unto himself another wife and then went to Hicks Bay. Always restless, this man continued his journey and, rounding East Cape, proceeded southward to Tolaga Bay. It was not long before we find him further south at Whangara. As soon as the people discovered his identity they took him to see the sacred footprint of his grandfather, the giant Rongo-kako, which was firmly embedded in the rock. The next footprint, known as Tupuae-a-Rongokako, was some thirty miles away. Unusual for Kahu, he remained some years at Whangara, and although he made journeys elsewhere he always came back to this place.

We now come to the wooing and winning of his favourite wife, Rongomaiwahine. While he was at Whangara Kahu heard of the fame and beauty of the Chieftainess Rongomaiwahine, who lived with her mother Te Rapa at Tawapata, on the Mahia peninsula. The reputation of this man had long preceded him. Leaving his wives at Whangara this much-married man proceeded to Nukutaurua and thence to Tawapata, where Rongomaiwahine lived with her husband Tamatakutai, and her mother, Te Rapa. Seeing the Chieftainess he became very much enamoured of her. Her husband was a Chief and a carver of wood, but a poor food provider,

Page 30

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

so Kahu set out to separate the two. He studied the people, their manner of life and their food supply and he soon made himself at home. By his cleverness, industry, and organisation he kept the kainga well supplied with fern-root, mutton fish or paua, and other kinds of food, and there was great feasting. He soon won the goodwill of the people and became a great favourite. The people realized the difference between Kahu and their Chief Tamatakutai. Kahu was a wonderful man, while their Chief, apart from his wood carving, was a waster.

Kahu, dining well one night on paua, retired to sleep in his corner of the Wharepuni, while Rongomaiwahine and her husband retired to another corner. In the night when Kahu knew by their gentle snoring that the other two were sleeping, he went over to their corner and played a rude joke on them and then darted back to his own corner and commenced to snore. Rongomai soon woke, and giving her husband a poke in the back with her elbow asked what he meant. The man, half-awake, denied that he did anything and blamed her for it, and after a short tiff they went to sleep again. When Kahu heard their gentle snores again he got up and again played the same joke on them. This time there was a serious quarrel between husband and wife and each vowed to leave the other in the morning. While this was going on Kahu listened and snored his approval.

The next day husband and wife separated just as Kahu wanted, and the people, seeing what a good match it would make, soon gave Rongomai to him for a wife, and she made no objection. She became his favourite and most celebrated wife and the parent of illustrious children. He took up his abode with his wife in the impregnable pa Maunga-a-Kahia, which is situate some eight hundred feet above the cliff, and commands a clear view right up the East Coast. They both lived to a good old age and Kahu died at this pa.

There were no stirring, warlike feats to redound to his glory; like his father Tamatea, and his grandfather, Rongokako, he was always a man of peace. This cannot be said of his children or grandchildren. They more than made up for his deficiency. His old age was embittered by the strife and quarrels of his sons and grandsons who, when not quarrelling with their neighbours, were quarrelling amongst themselves.

Page 31

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

The children he left at Kaitaia peopled the North, and by intermarriage formed a large branch, and there were also large families to his children along the East Coast at Gisborne and Mahia. They grew and multiplied and became one of the largest and most virile of the modern tribes.

Many Whakatauki or proverbs concerning this man and his doings have been made, and on account of a certain physical peculiarity (magnus penis) and of his affairs with women and their sayings, and also of his wooing of the fair Rongomaiwahine, the tales of this man are related with great gusto and are well known amongst the tribes today, and as long as the tribes last his memory will be evergreen.

CHAPTER II.

THE INVASION OF HAWKE’S BAY BY THE NGATI-KAHUNGUNU.

The following is a family tree of some of the principal participants in the incidents that follow: –

KAHUNGUNU

Kahukuranui

Rakaihikuroa

TARAIA

Te Rangitaumaha

Te Huhuti

TUPURUPURU

Te Rangituehu

Hineiao

TUPURUPURU.

This man was the great grandson of Kahungunu and was a prominent Chief of the ever-increasing Ngati-Kahungunu tribe. He lived some eighteen generations ago (about four hundred and fifty years), and was the fourteenth in the direct line from Toi. His father, Rakaihikuroa, was proud of his son, who was a rising Chief and became the person of the greatest mana at Turanga.

Page 32

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

There also lived at this time at Turanga another Chief by the name of Kahutapere, who had married Rongomaitara, the sister of Rahaihikuroa. These two were therefore the Uncle and Aunt of Tupurupuru. This couple had born to them twin children, by names Turakitai and Turakiiti. Tupurupuru became very fond of the twins and used to spend much time watching them at their play. Tupurupuru’s father, Rakaihikuroa, became jealous and feared greatly that these children would gain the ascendancy over his son. He became angry also over a certain incident connected with a papahuahua, a Maori delicacy, being birds preserved and cured in their own fat. These were given to the twins to eat, but Rakaihikuroa thought that they should have been given to his son, Tupurupuru, the Chief. It was in connection with a papahuahua that Kahu left his father, Tamatea, at Putiki.

Rakaihikuroa brooded over the matter and he made up his mind to destroy his sister’s twins. It was not long before he hatched a plot with this end in view, but being unwilling to carry out his own foul work he prevailed upon and directed his nephew, Tangiahi, to commit the murder.

The two boys were in the habit of spinning their tops at a certain place, and this place was noted by Tangiahi. He set to work and dug a large pit and carefully covered the top with sticks and turfed it. Another version is that this pit was a disused kumara pit beside the path. This was in Rakaihikuroa’s pa of Maunga-puremu, near the present township of Ormond. The plan succeeded. The children fell or were pushed into the pit, and as soon as they were entrapped Tangiahi filled it in. As evening came Kahutapere and his wife became anxious and searched everywhere for the children. They could not be found and no one seemed to know where they were. Kahutapere suddenly bethought of a novel idea. He had some kites made out of raupo and shaped like hawks and he let them off. They kept rising higher and higher until the wind carried them over the house in the Maunga-puremu pa, in which Rakaihikuroa lived. Unfortunately for Rakahikuroa when those kites mounted over his house they kept bobbing their heads again and again in the direction of his house. It was then known who had killed the children.

When the people in the pa saw these kites nodding down

Page 33

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

at them they became apprehensive. They tied a long string to a stone and threw it into the air over the string to which the kites were attached and pulled them down one by one. But it was too late, the little “birds” had done their work.

Kahutapere immediately went off to his pa Pukepoto and called his warriors and friends together and attacked the Maunga-puremu pa. There was a great fight. Tupurupuru and several of his people were killed, but Rakaihikuroa and others escaped. Kahutapere and his warriors went on the war-path and there was a great scattering of the people. That attack and defeat was known as the Paepae-ki-Rorotonga. They even gave a name to the stones and oven in which Tupurupuru was cooked.

The fugitives then fled in large numbers. They formed themselves into two large parties and went in the direction of Wairoa, one party going by way of the sea coast, and the other inland.

THE COASTAL PARTY. – The Coastal party had with it the following Chiefs who became leaders in subsequent fights: –

Rakaihikuroa

Rangitawhiao

Te Aomatarahi

Rahiri

Ruatekuri

Tupurupuru II, son of Ruatekuri

Tawhao

Taraia

Now, wherever these fugitives went, they found that the land was already peopled by various tribes and hapus, so that they would have to fight for a home and a footing in the land. Following the coast they travelled south to Nukutaurua, Mahia peninsula, at a place called Ukuraranga. The fugitives stayed at this place for some time until the Chief of the place, Kahu-paroro, arose to go to Turanga. When Takaihikuroa discovered his intentions he bade the Chief farewell and said, “Friend, go in peace to where my son rests and when you hear him crying after me let him rest,” meaning, of course, that the bones of his son were not to be disturbed.

When Kahuparoro arrived at Turanga he did not heed the old Chief’s warning, but collected all Tupurupuru’s bones and

Page 34

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

brought them back with him to Te Mahanga, near Mahia, and left the skull there. Although Kahuparoro did not know or foresee what his action meant at the time it made history and caused the death of hundreds of people. Kahuparoro then went on to Nukutaurua and secretly made fish-hooks out of Tupurupuru’s shoulder blades.

One of the principal foods of the Maori is fish, and Kahuparoro, who now was possessed of some wonderful hooks made from the bones of a great Chief, arranged a fishing party to go to their favourite rock, Matakana. When the sea was smooth they pushed off in their canoe. One of Rakaihikuroa’s men, Tamanuhiri, wishing to do a little fishing on his own account, jumped into the canoe with them, and they paddled out to the fishing-grounds and commenced fishing. Now Kahuparoro baited and threw out his line with the wonderful hook, and forgetting all else chanted a hurihuri or incantation. It happened to be very effective, for he soon hooked a large hapuku and began to play it. He commenced to talk to the fish as fishermen sometimes do, and jeered at it and told it not to hope to escape for was it not caught with a wonderful hook made from the bones of the great Tupurupuru? Now the stranger in the boat heard this, and found that it was as he had expected, the bones of Tupurupuru had been used. He then gave himself a blow on the nose and held his head over the side of the canoe as if in a faint, while his nose bled. This was a ruse to be taken ashore. The people of the canoe noticed that he gave every appearance of being ill, so they took him ashore and then returned to the fishing-grounds. Tamanuhiri immediately went to Rakaihikuroa and told him what he had seen and heard, and after a consultation it was decided to avenge this insult.

Meanwhile Kahuparoro and his party had a very successful day and returned to the shore in the evening with their canoe laden with fish. This fish was distributed among the people in the pa. As the weather gave every indication of remaining calm another fishing expedition was arranged for the next day. The refugees expected this and sent a strong party down to the landing-place, where it remained hidden. In the early morning the fishing-party came down to the shore and commenced to pull out their canoe, when they were

Page 35

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

suddenly set upon and attacked by the concealed party and were all killed. This massacre was known by the name of Te Humatorea.

The same man, Tamanuhiri, had by some other means or other discovered that a man named Hauhau had used some of Tupurupuru’s bones to dig for fern-root; this was looked upon as another great insult, and they determined to avenge it. Rakaihikuroa, who still remained there, went to look for a suitable place to dig fern-root, and having found it he thought he would call out the inhabitants of the place as a working-party to assist in the digging. They came out and set to work with the others. The fugitives from Turanga had their digging implements in their hands, while the local people were scratching in the soil, going deeper and deeper after the fern-root. At this stage, Rangitawhiao, of the refugees, started a chant. Many things can be expressed in a chant, and in this particular one the Chief incited his people and exhorted each one to watch his man. When the fern-root diggers had reached a good depth and were stooping down, at a given signal they were set upon and killed by the refugees from Turanga. That massacre was known by the name of “Hau-hau”. That was the last slaughter at that place to avenge the desecration of Tupurupuru’s bones. In that massacre one hundred and forty people were killed.

After this Rakaihikuroa, with his refugees, proceeded on his journey towards Wairoa, where they arrived in due course. In the massacre at Hauhau, a young Chief, Taraia, a brother of the dead Tupurupuru, came into prominence. After the refugees had been in Wairoa for some time they wished to cross the river. The local people had removed the canoes, so Taraia called to them to bring over the canoes as they wished to cross, but this the local people refused to do.

Now Taraia, besides being a very capable warrior and leader, was a very crafty young man, and knowing the curiosity of the Maori he resorted to a ruse to get possession of the canoes. He had a litter or sedan chair made and in this he placed a woman. This woman was his daughter, Hinekura, whom his people had made ready by making tattoo marks all over her body. They then danced a great haka. As the litter was being carried from place to place the people, according to

Page 36

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

instructions, flocked round it looking in. This excited the curiosity of the people on the other side of the river. First one of the inhabitants came over in his canoe and joined the throng round the litter and he was instantly clubbed and his canoe taken possession of. Then another one came over in his canoe and was treated likewise. Meanwhile that sedan chair was kept moving and local people continued to come over in their canoes and were all treated in the same way until Taraia had all the canoes he wanted and was thus able to cross the river. This massacre was called by the name of “Te Eketia,” on account of the boarding of the canoes. We will leave Taraia and his refugees here while we follow the travels and adventures of the Inland party.

THE INLAND PARTY. – The Inland party, led by Rakaipaka and Hinemanuhiri, journeyed through by way of Hangaroa to Waihau. There was at this time in the district a tribe of aboriginals called Te Tauira. They were very numerous and had several pas, the chief one of which was Rakautihia. It was into the territory of this tribe that Rakaipaka and his party came, and they remained at Waihau some time. It was not long before they found some reason for attacking this tribe. They felt sure of the conquest, so in order to avoid trouble after the conquest, they divided up the lands of the Tauira tribe amongst themselves beforehand. The attack was then launched and resulted in the complete defeat of the Tauira tribe. Many of them fled from the district towards Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa, where they had relatives and friends, whose hapus they joined.

About this time, at Turiroa, a place some three or four miles up the Wairoa river, there arose some trouble over a pet tui. The tui when taught is a splendid talker. The Chief there was Iwikatere. It was the custom of the Maori before planting their kumara and taro or sowing their seed, or commencing any other work to get the tohunga and have a ceremony. This tui had been taught to say the prayers and incantations used while the Maori planted the kumara and taro, so it became a much-prized and important bird. In the pa adjoining that in which Iwikatere lived there dwelt another Chief by the name of Tamatera. He became very envious of the owner of the bird, so one day he borrowed it. He omitted

Page 37

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

to return the bird, and after a long time the owner took it away. Now Tamatera did not like losing the bird, so he went at night and stole the tui.

The next morning Iwikatere, finding that his tui had disappeared and, knowing who had stolen it, immediately collected his warriors and attacked Tamatera and his people. Tamatera evidently expected this attack so was ready for Iwikatere, and so well did the thief and his people fight that Iwikatere was repulsed. Iwikatere now found that he could not by himself overcome his enemy, so he bethought himself of Rakaipaka and his refugees from Turanga, who were not far off, so went to him and invoked his aid against Tamatera. This was readily given, so the attack was made and a very fierce fight ensued. Many were killed on both sides. Tamatera and his people were beaten; he and another Chief called Taupara and many others were killed. The survivors, led by a Chief called Ngarengare, and his grand-daughter, Hinetemoa, fled to Heretaunga. Although these people were beaten by the two tribes at Wairoa they were good fighters. When these refugees arrived at Heretaunga the place was already occupied and they, in turn, had to fight to get a home for themselves. The Tane-nui-a-Rangi, who were in occupation, were defeated and driven out of their lands, and the refugees took possession of them and settled at Pakipaki, Poukawa and Te Aute.

The present name of Pakipaki is an abbreviation of the name Pakipaki-o-Hinetemoa. One hot summer day the grand-daughter Hinetemoa, when strolling along accompanied by her slave girl, came to a stream. She stationed the maid on the bank while she had a bathe; when she came out she slapped and rubbed her body by way of massage as bathers generally do, and thus gave rise to the name Pakipaki-o-Hinetemoa (the massaging of Hinetemoa).

When defeated, the survivors of the Tane-nui-a-Rangi fled inland to the seventy mile bush to a place near Dannevirke. Eventually a great fight took place here and they were defeated. The place got the name of Umutaoroa (the ovens that took a long time to cook).

Page 38

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

TARAIA’S RAIDS ON HERETAUNGA.

FIRST RAID. – Taraia, after the Eketia massacre, determined to make a raid on Heretaunga. He organised a war-party, picking his warriors mostly from the Ngai-Tamanuhiri and Te Aitanga a Hikuroa. Leaving the main body at Wairoa under the charge of the Chief, Taraia and his war-party left on their man-killing expedition. They journeyed overland, and the first pa of any note in their path was Aropaoanui.

AROPAOANUI. – Aropaoanui was a large and important sea-coast pa situated at the mouth of the Aropaoanui River. This place was visited several years previously by Tamatea and his son Kahungunu when they were greatly taken with its food supplies. It was also a port of call where canoes that came along the coast broke their journey. The last occasion this place was so used was when a large fleet of some fifty canoes from up the coast called on their way to the tangi when Sir Donald McLean died at Napier.

The people of this place were known as Te Aranga Kahutari. At the time of Taraia’s raid the Chief of this pa was Rakai Moari (of the overhanging eyebrows), otherwise called Rakai Weriweri (Rakai the Ugly), because he had a large wart on the bridge of his nose between the two eyes which made him look hideous. He was a distinguished warrior.

Some time previously to this Te Aranga Kahutari people were raided by a war-party from inland. So able was the defence put up by Rakai and his people that the raiders were defeated. The usual celebrations ensued, followed by the lighting of the hangis and the cooking of the slain. Here an incident happened that gave the name to the place. The cooks, on opening up the hangi and watching a portion of the human body therein, suddenly stopped in their operations and with eyes bulging and hair bristling stepped backward and then bolted. They told Rakai that the men they had killed and cooked were alive. What they had seen was the twitching behind the kidney fat which one usually sees in a beast after it has been killed and dressed for some time. Rakai, on hearing what the cooks said, jumped up suddenly and proceeded

Page 39

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

to the hangi and paoa nui (or thoroughly bashed) the offending portion. Hence the name Aropaoanui – the thoroughly bashed kidney fat.

THE WAIKOAU FIGHT. – Rakai was not taken by surprise by Taraia. Somehow he got to know that the raiders were coming and so, when they appeared, Rakai called out “Where is Taraia?” and Taraia replied, “Here I am.” Rakai then said, “Stand forth that I may know you.” Taraia did so. He was easily recognisable by his dress-mat of feathers. Rakai then said, “I shall know you presently, your heart shall be my food.” He then challenged Taraia to single combat. Taraia picked up a stone, reciting the tipihoumea (a short incantation) threw the stone, and so well was it directed that it hit Rakai’s putiki and knocked off his head-dress of feathers, which fell right at Taraia’s feet. It was then that Taraia called out, “I know that it is I that shall eat your heart presently.” Rakai the Ugly then came down from the pourewa, or staging of his pa, and engaged in mortal combat with Taraia. The fight between these two warriors was fast and furious while it lasted, but in the end the older Chief, Rakai the Ugly, began to get the better, and Taraia commenced to run. When the raiders saw what was happening to their Chief they began to stampede. It would have gone very badly with them if it had not been for Hinepare (Lady of the plumes), the wife of Taraia. She was the daughter of Tamanuhiri, who went out fishing in Kahuparoro’s canoe. She was standing on a big rock overlooking the fight, and when she saw her husband run she jeered at him for running away and leaving her to the mercy of the enemy. Her brothers heard her, so they turned round and stood their ground, so also did Taraia, who rallied his people, and they returned to the fight. The struggle that ensued was fierce and long, but Taraia prevailed and a large number of people were killed, including Rakai the Ugly. This was known by the name of the Wai Koau (waters of the shag) fight.

After a while the raiders moved on to Whakaari, near the headland at Tangoio. This place was used later as a whaling station. While here Taraia and his party had a visitor from

Page 40

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

Heretaunga. He was a friend of Taraia’s named Totara. In the course of his talk he boasted about the abundance and quality of the food in the district. It was then that Tawhao, one of the Chief in the Coastal party, said, “The Whanganui-o-Rotu” (the Inner Harbour) “shall be my garden” (Mara-a-Tawhao). Taraia said. “The Ngaruroro” (celebrated for its supply of kahawai) “shall be my drinking cup” (I pu-o-Taraia).

Taraia now turned his attention to the great pa at Heipipi, which was next in his path. Before proceeding with the account of his attack it will be worth while knowing something about the pa and its builders.

HEIPIPI (pipi-necklace). – About six or seven generations before the general migration in 1350 a canoe load of emigrants came to Aotearoa in the canoe Mata-atua, under their Captain Toroa, and landed at Tako. They were a branch of the Ngati-Awa people, who were a restless tribe and could not settle for long anywhere. Here they settled for a while and began to spread. They built a strong pa at Rangihu. It was not long before they reached Waitangi and Kerikeri, and gradually they went up these rivers, crossed over the ranges and went down by the Waihou river into the Hokianga country.

Here they built some very great fortifications, with underground channels, dug-outs, ruas, and food-stores. These people knew how to build, and they occupied a large tract of country.

Soon afterwards another Ngati-Awa canoe arrived with a further load of emigrants, who landed at Doubtless Bay and went over to Kaitaia. These people built a pa at Oponini, Hokianga Heads. Here then these two sets of people lived and kept in touch with one another for a few generations, when war broke out.

The Ngapuhi had arrived in their canoe from Hawaiki and landed south of the Bay and eventually settled in Hokianga. The Ngati-Awa had given offence to the local people, which gave rise to an attack led by Ngahere, a member of both tribes, and the Oponini pa of the Ngati-Awa was destroyed. A general war followed. The Ngapuhi of Hokianga joined in with Ngahere, and in the end the Ngapuhi prevailed and drove out the Ngati-Awa.

The Ngati-Awa came away in two canoes, one, under

Page 41

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION

their Chieftainess Muriwai, landed at Whakatane, and another went round the North Cape and down to Taranaki. In Whakatane, Muriwai’s people joined with the Ngati-Awa of Toi descent, and for some time lived on the banks of the Awa-a-te-Atua.

Later, under the two leading Chiefs, Wharepakau and Patuheuheu, they went further inland and built the Whaka-poukorero pa up in a mountain. They used this as their headquarters and spent their time hunting and killing the Urukehu, a harmless and weaker people of fair skins, who were driven into the bush and ranges. They were ultimately attacked and destroyed at Heruiwi.

They later left Whakapoukorero and came through to Motu, where they built another pa. From here a large section of the tribe known as the Mamoe or Whatumamoa came through to Hawke’s Bay, led by the Chief Te Koau Pari (the cliff shag). They built two very strong and large pas, one at Heipipi and the other at Otatara.

The Heipipi pa was built on the Petane hills, overlooking the sea about half a mile from the Petane village, with large dug-outs and communicating channels, and the stockade extended far up the hill.

The Otatara pa covered about eight to one hundred acres. It was of the village type and consisted of two pas, the upper one called Hikurangi and the lower one called Otatara.

Colenso, some nine-eight years ago, describes it as a strong defensive work of great extent requiring a great number of men to defend it and repel an attacking force. It was only one of the many visible spurs above the river which were fortified. It has a precipitous descent to the river bed and was in the immediate vicinity of good eel swamps and sea and river fishing. A military man visiting the site estimated that it would take ten thousand men to man and defend that pa.

Heipipi reached its zenith when Tu-nui-a-Rangi (standing out largely on the horizon, illustrious, or Tunui of Rangi descent) was its paramount Chief. He was a very high tohunga as well as a great Chief. He was a superman, with supernatural powers, and his fame went far and wide. The Otatara Chief at that time was Paritararoa.

Page 42

HISTORY OF HAWKE’S BAY

Taraia knew what he would be up against if he made a direct attack against that great pa, so he determined to take it by strategy if possible. Leaving Whakaari he came with his warriors along the coast. At a little lake on the way they caught a woman who was washing clothes. She was Hinekatorangi, Tunui’s daughter, and she was promptly handed over to the commissariat department. The lakelet or swamp, now dried up, has ever since been called Te Wai-o-Hinekatorangi. As the sentinels at Heipipi could see far and wide from their look-out, Taraia waited until the darkness of night before he proceeded any further. Leading his warriors he came down to the sea-shore below Heipipi. He then told them his plan. Those with dark garments had to lie about, some on the shore, while others were to be tossed about by the waves so as to resemble blackfish being stranded, whilst he and the rest would hide close by. In the early morning they put this plan into operation. In the first streaks of dawn the look-out from the tower noticed the stranded blackfish and aroused the people, who made their way down the hill to the shore to capture their prize. Tunui came out on to the hill and watched them. When they reached the shore the warriors in ambush suddenly sprang out and proceeded to capture and kill them. Tunui, noticing this, suddenly cast incantations over them and the captives slipped out of the hands of the raiders. Taraia, noticing the man on the hill, asked him [if] he was Tunui, and, on being assured that he was, asked him to come down to the shore. Tunui came, and they rubbed noses and made peace, so there was no fighting. After this, Taraia, desiring some paua or mutton fish, asked Tunui if there were any near, and was told of a plentiful supply at Parimahu, a place on the coast beyond Porangahau. Taraia and his party then proceeded to Keteketerau, the outlet of the Inner Harbour, near Petane. This harbour now had the name of Te Mata-a-Tawhao. Tunui, leaving his people, went away to a cove in one of the islands in the Inner Harbour, where he kept a pet monster called Ruamano, which he used as a horse. When next Taraia and his people saw him he was riding his monster past them through Keteketerau out to sea. It is said that he rode round the Kidnappers and eventually landed on the shore at Waimarama.

Page 43

NGATI-KAHUNGUNU INVASION