- Home

- Collections

- CROSSE PB

- History of Patoka Station During Its Occupancy By TE & HE Crosse

History of Patoka Station During Its Occupancy By TE & HE Crosse

HISTORY OF PATOKA STATION DURING ITS OCCUPANCY BY T.E. & H.E. CROSSE

The property was managed by me from 1922 to 1935 on behalf of my father, and since then, as proprietor.

This property was purchased in 1902 and was then approximately 10,800 acres; of this 6,800 acres on the eastern side of the Napier Puketitiri road is mainly easy rolling country carrying a considerable overlay of volcanic pumiceous dust. The balance of approximately 4000 acres on the western side of the Napier-Puketitiri road is very much more solid country without volcanic overlay. This absence of volcanic overlay is probably due to the fact that this block is very much steeper than the country across the road, and it would seem the volcanic showers were blown off and washed off. The whole country is very subject to high winds and has an annual rainfall of 58 inches.

Pasture Establishment:

The whole block was originally a fern country, very much cut up by stock proof gorges. The farming policy up to 1900 was breaking in by firing successive blocks and sowing a certain amount of danthonia and then crushing with heavy mobs of dry sheep. Manuka was already a threat wherever the fern was crushed out. At that time danthonia was the only grass that could be expected to persist, suckling clover was a boon in the spring and early summer, while the young fern gave an enormous quantity of feed between October and February. Cocksfoot grew well but could not persist on account of the fact that the staple feeds were all summer growths and stock were on very short rations over the late winter and early spring periods. This meant that the cocksfoot plants were eaten out.

To overcome this starvation period and bring the country into higher productivity, ploughing was undertaken on a fairly large scale. A crop of swedes would be grown and eaten off in the winter. The paddock then lay fallow during the summer, worked up again and laid down in the Autumn. English grasses were sown but very little grass fertilising was done, and after a very few years the English grasses failed and the pasture was predominantly danthonia with a sprinkling of white clover and good growth of suckling clover in the spring and early summer.

It became quite apparent that English grasses were a failure under the existing conditions. Nevertheless the necessity of growing winter feed and the early promise usually given by the young grass induced us to continue the practice.

By 1917 practically all the land within easy reach of the homestead had been ploughed and second ploughing was going on. Grass did no better and the swede crops tended to fail. By 1922, swedes, except in virgin land, had become a very risky crop. Aphis had increased enormously, bitter pit was quite common and the weight of crop had dwindled very largely.

We stopped ploughing for two years, reduced the ewe flock and slightly increased wethers. However the difficulty of wintering hoggets

(2)

forced us to grow winter crops again. Soft turnips and chou-moellier were tried in addition to swedes on the grounds that one or other of the crops would succeed.

It was by then quite clear that far thicker pasture had to be established and maintained, since wind got into thin pastures and destroyed the root system of the plants, and Manuka, pimelia, bidi-bidi and other highly undesirable growths started in the thin pasture and quickly choked the entire sole of grass. On such pastures the sheep droppings were practically insoluble and useless as manure.

Up to 1924 sporadic fertilising had been carried out, usually a good year led to something being tried, but usually basic slag or blood and bone, both gave results but lacked quickness in action. Lime appeared to be a failure, and I still consider that lime is not the answer in this class of country. On the whole we had failed to produce English grass and consequently the incentive to plough in really large areas was lacking.

As I have said, manuka was a threat when we took over the property. The threat grew to a very serious menace and as fern receded with crushing, manuka took possession. Much the same technique followed with manuka as with fern. The manuka was cut and burned, grass was broadcast and succeeded for a short time. The initial success of grass was most probably due to the potash of the burnt manuka. After the fires there was no worm infestation and sheep did well. However successive cutting of manuka produced thinner and shorter lived pasture and consequent quicker reinfestation of manuka. It is one of the tragedies of this country that any bare bit of land instantly produces some harmful plant rather than a useful one. By 1926 it appeared to me that cutting manuka was rapidly becoming uneconomic.

It consequently became essential that any land ploughed must be brought into a state of reasonable English grass pasture. The very first necessity was to achieve a reasonable degree of consolidation. In this spongy type of pumiceous soil the use of a heavy roller is not satisfactory, it produces a consolidated film on top but in doing so powders the soil to such an extent as to make it liable to blow, and in any case the film is too thin to be a solid root bed. The problem then was to produce a pasture very quickly and sufficiently luxuriant to feed the mouths of enough sheep or cattle to carry out the consolidation in the shortest possible time. Given these conditions the sheep droppings are soluble and become the chief source of plant food.

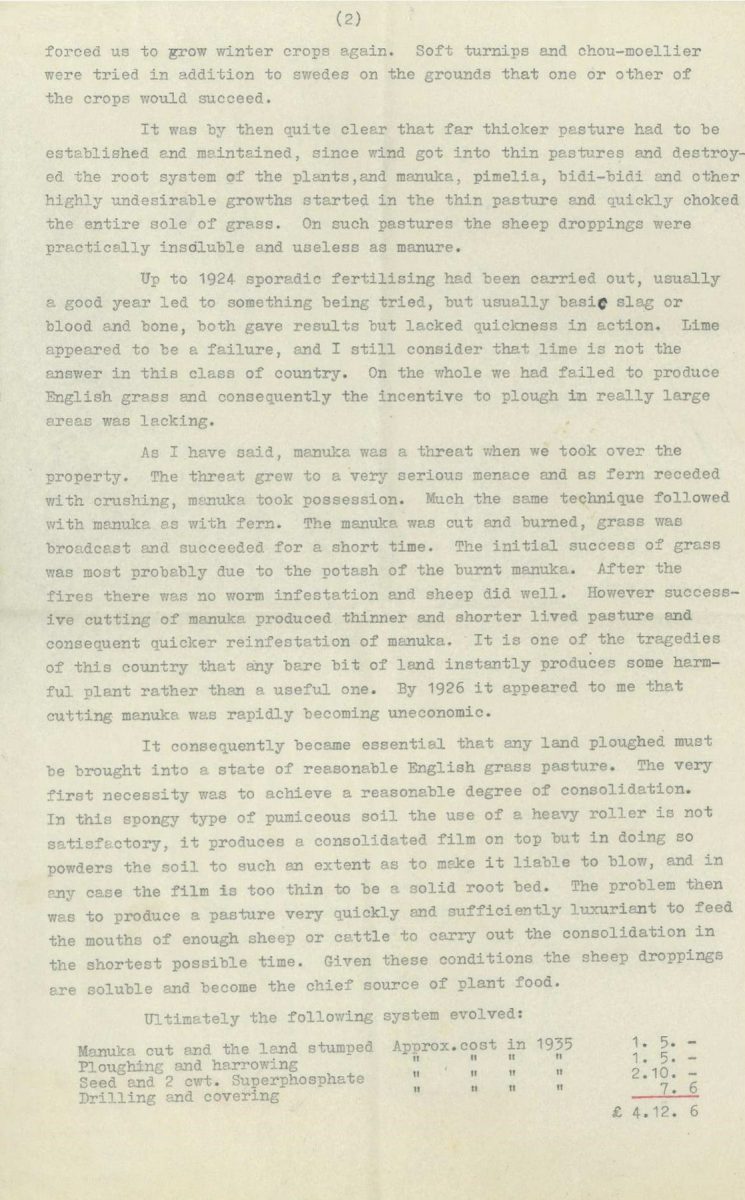

Ultimately the following system evolved:

Manuka cut and the land stumped Approx. cost in 1935 1.5. –

Ploughing and harrowing Approx. cost in 1925 1.5. –

Seed and 2 cwt. Superphosphate Approx. cost in 1935 2.10.-

Drilling and covering Approx. cost in 1935 7.6

£4.12.6

(3)

The seeding per acre was:

Perennial Rye grass 25 lbs.

Cocksfoot 3 lbs.

Crested dog 2 lbs.

White clover 2 lbs.

Subterranean clover 2 lbs.

Cowgrass or red clover 2 lbs.

Soft turnip 1 lb.

Seed of good germination and type was proved to be essential to success.

The same system today, however, is not economic, as costs have varied as under:

Manuka cut and stumped 3.10.-

Ploughing and harrowing 3.7.-

Seed and 2 cwt. superphosphate 4.15.-

Drilling and covering 12.6

£12.4.6

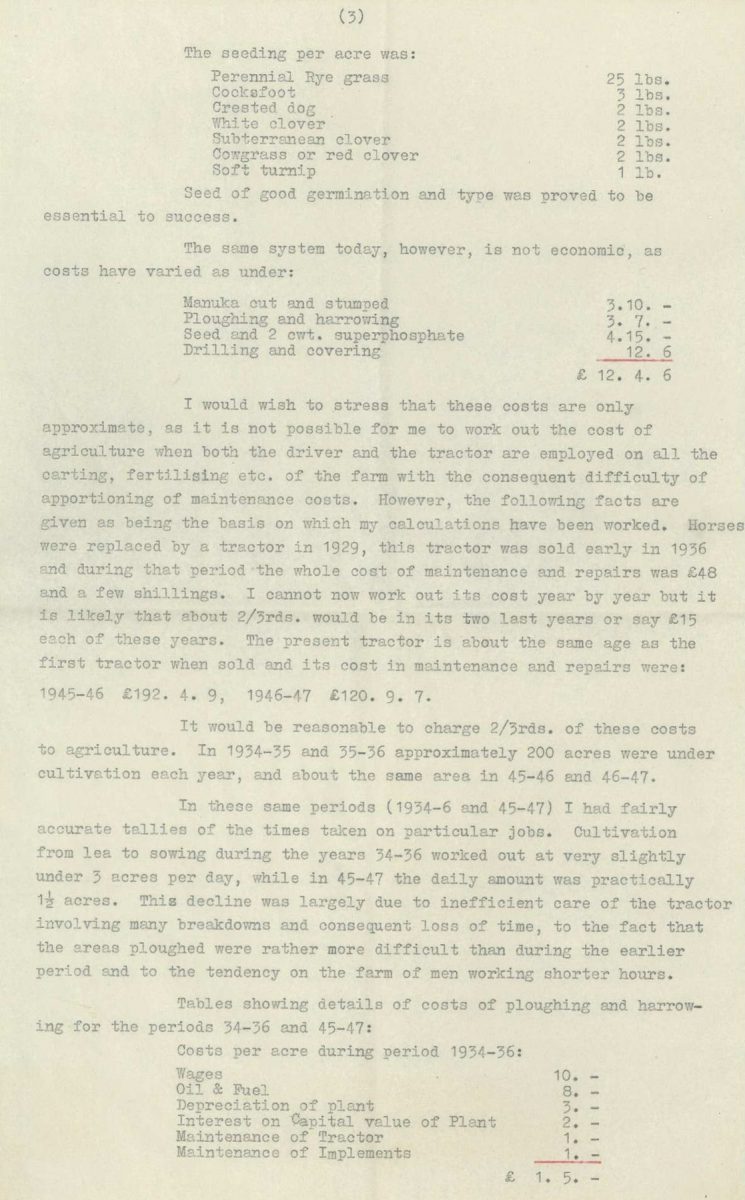

I would wish to stress that these costs are only approximate, as it is not possible for me to work out the cost of agriculture when both the driver and the tractor are employed on all the carting, fertilising etc. of the farm with the consequent difficulty of apportioning of maintenance costs. However, the following facts are given as being the basis on which my calculations have been worked. Horses were replaced by a tractor in 1929, this tractor was sold early in 1936 and during that period the whole cost of maintenance and repairs was £48 and a few shillings. I cannot now work out its cost year by year but it is likely that about 2/3rds. would be in its two last years or say £15 each of these years. The present tractor is about the same age as the first tractor when sold and its cost in maintenance and repairs were:

1945-46 £192.4.9, 1946-47 £120.9.7.

It would be reasonable to charge 2/3rds. of these costs to agriculture. In 1934-35 and 35-36 approximately 200 acres were under cultivation each year, and about the same area in 45-46 and 46-47.

In these same periods (1934-6 and 45-47) I had fairly accurate tallies of the times taken on particular jobs. Cultivation from lea to sowing during the years 34-36 worked out at very slightly under 3 acres per day, while in 45-47 the daily amount was practically 1 ½ acres. This decline was largely due to inefficient care of the tractor involving many breakdowns and consequent loss of time, to the fact that the areas ploughed were rather more difficult than during the earlier period and to the tendency on the farm of men working shorter hours.

Tables showing details of costs of ploughing and harrowing for the period 34-36 and 45-47:

Costs per acre during period 1934-36:

Wages 10.-

Oil & Fuel 8.-

Depreciation of plant 3.-

Interest on Capital value of Plant 2.-

Maintenance of Tractor 1.-

Maintenance of Implements 1.-

£1.5.-

(4)

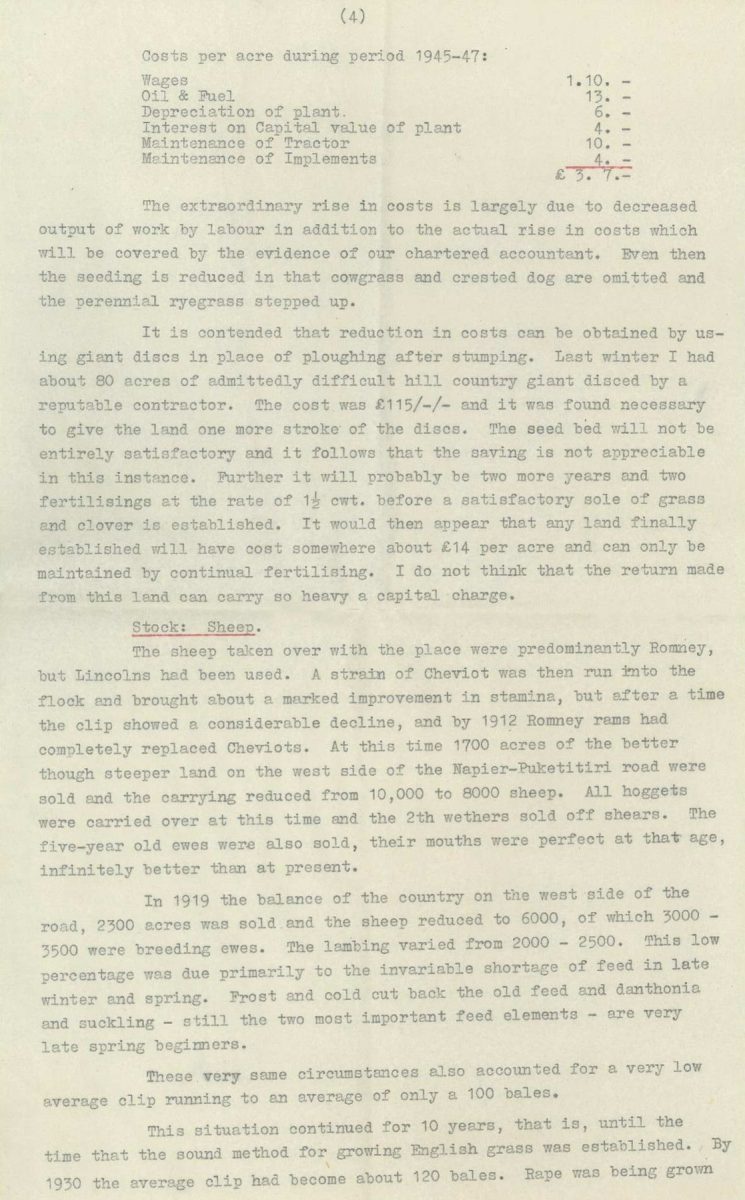

Costs per acre during period 1945-47:

Wages 1.10.-

Oil & Fuel 13.-

Depreciation of plant 6.-

Interest on Capital value of plant 4.-

Maintenance of Tractor 10.-

Maintenance of Implements 4.-

£3.7.-

The extraordinary rise in costs of largely due to decreased output of work by labour in addition to the actual rise in costs which will be covered by the evidence of our chartered accountant. Even then the seeding is reduced in that cowgrass and crested dog are omitted and the perennial ryegrass stepped up.

It is contended that reduction in costs can be obtained by using giant discs in place of ploughing after stumping. Last winter I had about 80 acres of admittedly difficult hill country giant disced by a reputable contractor. The cost was £115/-/- and it was found necessary to give the land one more stroke of the discs. The seed bed will not be entirely satisfactory and it follows that the saving is not appreciable in this instance. Further it will probably be two more years and two fertilisings at the rate of 1½ cwt. before a satisfactory sole of grass and clover is established. It would then appear that any land finally established will have cost somewhere about £14 per acre and can only be maintained by continual fertilising. I do not think that the return made from this land can carry so heavy a capital charge.

Stock: Sheep.

The sheep taken over with the place were predominantly Romney, but Lincolns had been used. A strain of Cheviot was then run into the flock and brought about a marked improvement in stamina, but after a time the clip showed a considerable decline, and by 1912 Romney rams had completely replaced Cheviots. At this time 1700 acres of the better though steeper land on the west side of the Napier-Puketitiri road were sold and the carrying reduced from 10,000 to 8000 sheep. All hoggets were carried over at this time and the 2th wethers sold off shears. The five-year old ewes were also sold, their mouths were perfect at that age, infinitely better than at present.

In 1919 the balance of the country on the west side of the road, 2300 acres was sold and the sheep reduced to 6000, of which 3000 – 3500 were breeding ewes. The lambing varied from 2000 – 2500. This low percentage was due primarily to the invariable shortage of feed in late winter and spring. Frost and cost cut back the old feed and danthonia and suckling – still the two most important feed elements – are very late spring beginners.

These very same circumstances also accounted for a very low average clip running to an average of only a 100 bales.

This situation continued for 10 years, that is, until the time that the sound method for growing English grass was established. By 1930 the average clip had become about 120 bales. Rape was being grown

(5)

and the wether lambs fattened, the ewe flock increased and the lambing improved.

In 1933 the block of 2300 acres sold in 1919 came back on our hands but was again sold in 1936. During these years production of the rough country was maintained through cutting manuka assisted by unemployment subsidies. Without these subsidies, it was by then definitely uneconomic.

By 1938 about 900 acres were well established in English grass, the rough country was carrying approximately 3000 sheep. Breeding ewes were 4400 and lambing 3800 of which 650 went off the mothers and 1100 off rape.

The carrying then was 7000 and increased with new pasture and improvement of existing pastures to 7500. Lambing was over 4000, the clip 155 bales.

With the outbreak of war cutting manuka ceased and the rough country simply hurried on its decline. Today it does not carry anything regularly although a small number were on the block for about 5 weeks during winter.

During the war my manager persued [pursued] the policy of ploughing the old danthonia paddocks and on my return had increased the breeding ewes to 5000 and the clip to 190 bales. This in spite of the deterioration of the rough country and the enormous reduction in fertiliser. The total flock still stood at about 7500 in 1945.

Cattle:

The country is not suited to cattle largely owing to the fact that in the early stages the creeks are very boggy and then run into precipitous gorges which means that losses through bogging and going over cliffs are heavy. Nevertheless cattle play such an important part in establishing new pastures in this very light land that it is necessary to carry as many as possible. From 1902 to 1928 the numbers varied between 60 to 120, between 1928 to 1938 the numbers moved up to 350. Aberdeen-Angus bulls have been in use for 35 years. The number remained fairly constant for the next 5 years.

Rabbits:

It will be noticed that the figures for sheep and cattle have both stopped at 1944. The first rabbits appeared on Patoka about 1885 and one of the station hands was duly turned into a part time rabbiter, but by 1902 rabbits were established in small numbers and from then on rabbiters were in constant employment. It would probably be correct to say that the kills of rabbits between the years 1902 and 1939 varied only between 100 and 200 per annum. I returned to Patoka in October 1944 to find rabbits everywhere, and from then on they came like a dirty mountain torrent in flood. It may interest the commission to know that the first letter on a file of 2-N.Z.E.F. dealt with the farce of keeping an experienced rabbiter, who had become permanently unfit, in Egypt, when he would be doing far better service destroying rabbits in New Zealand than peeling potatoes in Egypt. This file dealt from then on with the return

(6)

to N.Z. of permanently graded men who were engaged in primary industry in civil life and was the means of returning thousands of farmers and farm labourers.

For the years 1945-46 46-47 no fewer than 120,000 have been killed on Patoka – in the two years. I hope that for 47-48 the figure will have dropped to 30,000.

The effect on the stock carrying has naturally be deplorable and sheep are now down to 6000 and cattle to 80. These figures do not show the full depredations of the rabbits because 400 acres of English grass have been laid down during the period which should have brought (taken in conjunction with the increase in the superphosphate ration) the carrying capacity up to 8,500.

Finance:

Balance sheets do not mean very much in connection with a farm of this sort. My father owned the property up to 1933 and had multifarious interests in and out of N.Z. his affairs became so involved in the slump that I took over Patoka with its mortgage and some other liabilities. I then knew that the only road to solvency lay across the English grass paddocks and I was confident that I could produce such paddocks. Up to 1944 everything was done to this end and the place had become a very sound farm. The accumulation of increased costs, wages, rates, added to a drought and a flood of rabbits have brought me back to the point of being a nightmare to my banker and mortgagee. On top of this the new price of super is simply the end of the road.

Labour:

The general shortage of labour added to the shorter hours in industry, better conditions and greater availability of married quarters have naturally all tended to draw manpower to the towns. The shortage of country labour, again quite naturally, means that the better class of country labour can get the jobs nearer the towns with the benefits of town amusements, electric power, sports – gregariousness (few men and fewer women are really suited to the monasticity of the back blocks.) All these factors increase the difficulty of staffing poor back country stations with good type of labour. It would be equally true to say that the back country’s need for the best type of labour is far greater than that of good country. I have said before that the output of work of the majority of farm workers has fallen to a deplorable extent. This statement is clearly shown by the following:

During the war the Manager of Patoka engaged an elderly man who was considerably incapacitated. For this reason the man was engaged at appreciably less than current wages. He worked here for some years and was then employed by the same manager to work on his place on approximately the wage he had been receiving here. A few months ago he asked for a rise. His employer pointed out that he was five years older than when first taken on and since age was then one of the disabilities rendering him an underrate worker, it was obviously a greater disability now. The man agreed that he was certainly no better, but to him the

(7)

point was that the output of the normal worker had fallen so far that he was at least as good as the next man. His employer agreed that his assertion was correct and put up his wage.

Taxation:

Rates H.B. Council 1936 – £128.13.10 1947 – £385.18.10

Graduated Land Tax 1936 £89.-.11 1947 – £167.10.5

The question of county rate is dealt with under the heading Transportation. The Land tax does not appear to be justifiable on any grounds whatever, originally it was designed to force the breaking up of large holdings. In that respect its use has long since disappeared since there appears to be ample legislation to enable the Government to acquire any land it likes. There can be no excuse for demanding from me the sum of £167.10.5 simply because I am the registered proprietor of Patoka, a property which was reported on by the Lands and Survey Department as quite unsuitable for closer settlement.

Income Tax:

This type of country tends very much to extremes. One has an occasional very good year and two or three very bad years. This tendency exists of course to a degree in all types of farming.

From point of view of Income Tax it is extraordinarily difficult in that a frightful year following a bumper year means that in the middle of a difficult time one makes actual payment on the amount made in a good year. Any business which requires the whole 12 months to produce its crop is at a disadvantage as there can be no evening out of receipts and expenditure.

It would be of immense advantage to the whole of New Zealand if income derived from farming were taxed on a three or five year cycle. Farmers would be able to plan their work with far more elasticity and improvements would be carried out continuously instead of being carried out in lumps during good seasons. The result from a national point of view would be steadily increasing production at a considerable faster rate than at present.

Power:

There can be no question but that, morally, the most remote farmhouse has equal right to electricity as the office of the local power board. The supply of electric power is as much a national duty as the delivery of letters. Yet this principle is not worked on. In the case of a letter the cost of postage is the same whether the letter is delivered in the next street or a thousand miles away. It is far otherwise with power, a country district asks for power, the whole cost of reticulation is worked out by the power board concerned, and the interest on that cost plus depreciation is hung on to the necks of the group asking for power. That forms a similar burden as would be the case if a man were

(8)

asked to find interest and sinking fund on buildings, ships, planes vans and personnel employed by the P. & T. merely because he posted a letter to an address in say, the U.K. there is no doubt that electric power is one of the very greatest boons of modern times and its absence in remoter districts forms one of the most severe drawbacks to such districts. It seems that very much more determined efforts to supply power to remote country districts should be made by both Government and Power Boards.

Transportation:

It is agreed that state and main highways are essential to the development of New Zealand. Unfortunately the cost of the development of these roads has fallen far more heavily on the back block farmer than on any other section of the community. When the policy of making and maintaining high class roads was embarked on, it was decided that such work should be paid for out of benzine [benzene?] tax. The pleasure motorist was, naturally, quite agreeable to this since he was going to get more pleasant motoring conditions and reduced car maintenance costs. The ordinary commercial user was also quite agreeable in so far as added transport costs simply increased the cost to the public of the goods in which he dealt. Normally his carting is over long distances over rough roads, very little of which are assisted by main highway funds. Yet these very facts entail undue quantities of benzine being burned with the resultant enormous contribution to main highway funds. The funds are spent on roads which are used far less by the hill country farmer than by any other section of the people. Incidentally this benzine tax is now payable to the Consolidated Fund, and forms another heavy and quite unjustified drain on the hill country farmer in that his production costs are automatically raised.

Now it is held that cartage is based on a flat rate per ton per mile. Patoka Homestead and Waipukurau are practically equidistant from Hastings, the general rate from Hastings to Waipukurau is £1/-/- per ton, while to Patoka it is £1.19.-d. The answer is the difference in the two roads over which the two deliveries are made. Manifestly the answer is quite wrong, settlers in the Patoka area in fact paid much more toward building the Waipukurau road than did the Waipukurau settlers and thus gave cheaper transportation to Waipukurau, while at the same time the Patoka settler were unable to rate themselves sufficiently heavily to maintain even a reasonably passable road. To illustrate the amount supplied to the Main Highways by the back country the following figures are illuminating. In 1938 I made enquiries of some of the carriers operating in the Puketapu riding (the riding of the H.B.C.C. in which I am situated) and from what they told me of their benzine consumption I came to the conclusion that the Main Highways Board obtained revenue to the extent of probably £3000 per annum from benzine burned within the riding by heavy license vehicles. There are eleven miles of Main Highway within the riding, the actual cost of maintenance of which was about £130 per annum. This amount would be more than provided for by benzine used in the ordinary motor traffic within the riding.

(9)

Another feature of transportation seems worthy of consideration. In the immediate environs of Patoka six farmers do the whole of their carting (except sheep) and it is noteworthy that NO farmer who has undertaken his own cartage in this area has ever[y] discontinued the practice, which strongly suggests that the prices fixed by the Transport Authority are too high. In addition a great deal of the road work carried out by trucks sent out daily from Napier could be done more cheaply and expeditiously by farmer owned trucks. Working time of gangs sent up from Napier to work round Patoka very often works out at considerably less than 6 hours per day and the amount of benzine used in transporting two or three men from Napier to Patoka daily in a heavy truck is, in view of the insistent demand of the Government to save petrol, simply preposterous. Yet by law, the privately owned truck may not carry out county council work.

Another serious burden to hill country farmers is the upkeep of access roads. The further from town you go, the more road signs marked NO EXIT occur. Usually these roads serve one or two settlers whose entire rate do not cover the costs of what are virtually their own private roads. A particular case in this riding is of a road about 5 miles long and costly in maintenance – in 1934-38 the average maintenance was £140 per annum while the only farm served by it paid £8 per annum towards the upkeep of all riding roads. It is quite obvious that every farm has a right to an access road, but it is equally obvious that the cost of this road should not fall on his immediate neighbours. The answer is quite obvious, Railways are national, Airways are national, certainly highways, whether State highways or dedicated back block mud tracks should be equally national.

General Conditions:

In the immediate vicinity of Patoka practically every farm is on the market or has recently been sold. Patoka itself has abandoned 4000 out of less than 7000 acres, another farm of approximately 2000 acres two miles away is entirely abandoned, although about 150 acres have been broken in; my next door neighbour has ceased to stock more than half his property, his carrying was 2500 and now is 1200. The block of Patoka mentioned earlier as having been sold carried more than 4000 sheep twenty years ago, now carries 2500. The block on the north eastern boundary of Patoka now only stocks country which has been ploughed and laid down.

Conclusion:

25 years ago this block of 6800 acres carried approximately 6000 sheep spread more or less evenly over the whole area and this flock had an annual lambing of 2300 and produced a hundred (100) bales of wool. Today the same number of sheep is carried on about 2500 acres of which less than 2000 are in English grass, the lambing this year was 3900 and the clip was 161 bales, yet the country is still heavily infested with rabbits and about 50,000

(10)

have been killed on the 2500 acres of improved country. Of the balance probably more than 2000 acres are ploughable and capable of carrying 6000 sheep, yet it seems destined to continue in a state of desert. 30 years ago Te Haroto Station carried 20,000 sheep, today that station is desert with her[e] and there an old fencing post and bits of old rusty burnt wire. Since then the desert has leaped the Mohaka river and established itself on most of the N.W. slopes of Titiokura and Te Whaka and has thrust out fingers to claim much of Patoka and Glengarrie [Glengarry], Bennetts, Powdrells, Te Kowhai – all within 30 miles of Napier.

The reclamation of most of this country is possible but uneconomic on the short time view. It is however, a very real national asset and should be salvaged. The first essentials are:

(a) Derating

(b) Abolition of Land Tax

(c) Cheap Fertiliser

(d) Subsidy paid on every acre reclaimed to the satisfaction of the Lands and Survey Dept. I believe that in about the 80’s Bush Land in the 40 mile bush area was granted to owners of land on the Heretaunga plains on condition that planting of trees was carried out on the Heretaunga plains. The present production of the 40 mile bush area surely is ample justification for such a step.

(e) Reasonably cheap rural housing. There seems at present a lamentably different system applied to rural as opposed to urban Government housing schemes. The Government are direct landlords in the case of urban housing, while in respect of rural housing, the Government expects Local Bodies to act as unpaid agents who, in addition, guarantee the rents.

(f) Access roads which do not suffer as much as at present by comparison with State and Main Highways.

(g) Electric power

(h) It would appear desirable that the Plant Research Department make greater efforts to produce grasses and clovers suited to the poor country type. It is likely that very few suitable new grasses or plants will be found, but a Research Station situated in typical poor country should produce types of existing grasses which would succeed in poor country conditions.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.