- Home

- Collections

- Anonymous 2022

- Links in the Chain

Links in the Chain

LINKS IN THE CHAIN

By A.H. Bogle

With a Foreword by SIR DAVID SMITH

L.L.M. HON D.C.L. (OXON) HON L.L.D. (N.Z.)

JUDGE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW ZEALAND 1928-1941

CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ZEALAND 1945-1961

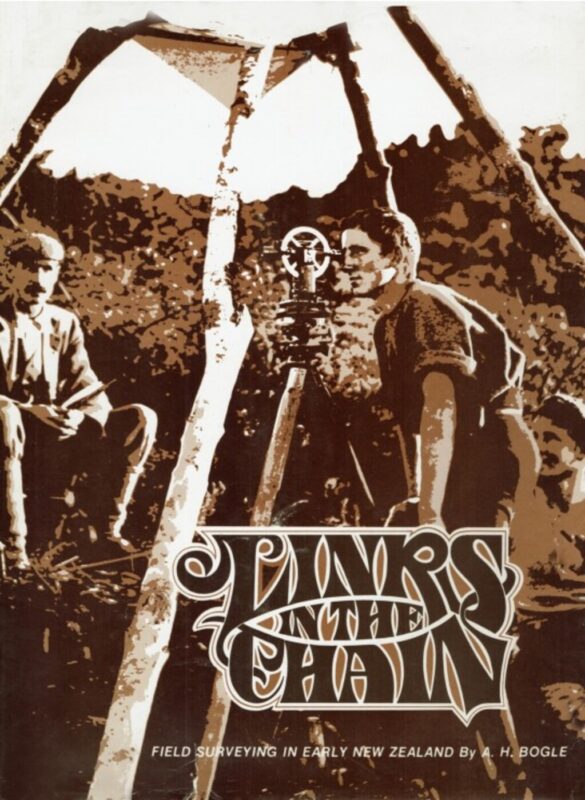

The field surveyors who opened up the New Zealand countryside for settlement, farming and industry were a race apart in more ways than one. They were men of independent spirit, yet imbued with a great sense of togetherness, enabling them to overcome tremendous physical odds. They were also called upon to endure months of isolation, often in inhospitable surroundings far from their homes and kinsfolk, requiring them to adapt socially and emotionally to an entirely alien existence. Archie Bogle, who tells his story in this book, was among the last of the field surveyors and during his long and eventful career, the doyen of his profession. He typifies the adaptability, the earthy sense of humour, the understanding and tolerance cultivated by men compelled to band together in trying circumstances and inevitably thrown into contact with people, who, for good or ill, their professional operations vitally affected but who came to respect the surveyors for the human qualities they possessed.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

“Haere ra!’’

I became a member of the Survey Board in 1939 and in the same year took on the editorship of “The New Zealand Surveyor.” I remained a board member, an examiner, and editor for 30 years and even acted briefly as board secretary when the regular secretary was away sick. Practically every surveyor now registered in our present institute up to 1968 passed through my hands at one time or another. It is really something to have spent a long life at professional work well worth doing, in close contact with men well worth knowing.

While a member of the board, I was sent to Australia four times to represent New Zealand at conferences of the Reciprocating Survey Boards of Australia and New Zealand. The first time I went alone to Melbourne, and on later occasions was associated with Messrs R. G. Dick (twice), and R. P. Gough, both former Surveyors-General. They were wonderful gatherings; apart from the experience of wide travel in a new land, surrounded by every hospitality. We had the great benefit of man to man meetings with senior survey experts from all over Australia. Many became old and trusted friends, still remembered with thanks and gratitude.

In 1950, the usual four-yearly boards conference was held at Wellington and was made the occasion of a large assembly of representatives from all English-speaking survey authorities, including the United States of America.

To give our guests some slight idea of the manifest advantages of our favoured land, a bus trip to Napier was organised. Anyone who knows Hawke’s Bay will remember how, some two miles short of Waipukurau, the road from Takapau rises to a ridge crowned by the Pukeora Sanitorium. From that point a clear view may be had for 10 miles or so straight down the valley of the Tukituki River, which cuts through the middle of the lovely township of Waipukurau.

I was armed with a megaphone, explaining to our guests all the features of the shining landscape. We were on the rise, ready to descend, and on a sudden impulse I said over the megaphone: “Attention all! Will you please observe strict silence for the next two minutes.” It worked perfectly, until some restless traveller asked what all that was in aid of.

“Nothing much,’’I said, “It just happens that I was born here.’ Believe it, if you can, that kept them quiet for another two minutes at least.

It kept me quiet, too. As we passed on down the road, there was scarcely a hundred-yard stretch on either side that did not hold some point or feature an old shack, a plantation, the lake or river bank which called up the past in vibrant recollection of days long gone.

The home of my childhood was the stationmaster’s house, which stood on the approach road to the railway station itself, about 50 yards from where the main road crosses the railway line.

Page 82

The kindly tourists wanted to know the exact location, but, as far as I could judge, a modern service station now stood on the site.

There were few spots within a three-mile radius of Waipukurau that had not known the barefoot trails of my three brothers and myself and several other exploring companions. As far as I know, I am the sole survivor. We all went away to the First World War. In my own family, I alone came back. My brothers bones lie scattered far from Waipukurau: Gilbert with the New Zealand Rifle Brigade on the Somme; Gordon with the Australians at Ypres; Stafford with the Royal Engineers on Gallipoli.

“Haere ki te kainga, haere ki te iwi, haere ki te po. Haere!”

Page VII

APPRECIATION OF A.H. BOGLE

BY

THE HON. SIR DAVID SMITH

For about three years before his death on March 14, 1972, my old friend Archie Bogle had been recording his experiences as a surveyor from youth to middle age. He was then approaching his ninetieth year and was in failing health. So his project was a characteristically gallant venture.

He had helped much to open up the untamed central parts of the North Island for settlement and it was of that enterprise, almost exclusively, that he made his record. He could, of course, have dealt with many other important matters. He had held all the offices of the New Zealand Institute of Surveyors, including the editorship of its journal for 38 years, and the presidency twice, from 1931 to 1933 (during the economic depression when the surveyors were badly hit) and again from 1955 to 1957. He had become a Fellow of the Institute. He had received its highest award, the Fulton Medallion (Class Al) for outstanding service to the Institute and his profession. In his honour, the Institute had established the Bogle Award for the benefit of promising young surveyors.

He had also been a member of the Survey Board for 40 years, a member of the first Town Planning Board and of the Geographic Board. He had, for long, been unquestionably, the doyen of the surveying profession. He had also served in both World Wars and had received the honour of Commander of the British Empire.

Behind all these distinctions and activities lay much important work and a knowledge of the New Zealand situation in relation to it. Yet, at the end of his life, when he came to survey the past and to consider what, if anything, he should leave on record for posterity, it was his active life as a pioneering surveyor that came to the top. So we have this book. It is surely a fine achievement, especially for one of his years, in failing health.

Archie Bogle had not kept a diary and he regretted the fact. But his memories, refreshed by past accounts of them to his friends – for he was a born raconteur – sufficed with a little research, for his purpose. His style is episodic. He creates pictures for the mind of incidents and scenes, from which the whole life of the early surveyor may be visualised. The style, too, has the graces of understatement and of humour.

We can enjoyably sense the surveyor’s love of the open air, the bush and the birds. We can appreciate the friendly relations of “the boss” and his assistants, whether Pakeha or Maori, though sometimes there was trouble with the cook naturally enough when a good meal at the end of a long hard day was of prime importance. On the other hand, we can sympathise with these hardy men when the rains descended and the floods came, when the Wanganui River presented endless problems as a highway, when unbridged streams had to be crossed, when clothes were sodden in bitter weather, when precipitous faces had to be negotiated and when accidents even unto death, had to be dealt with.

So, while the book should entertain its readers of today, it should also bring home to them, as they bowl across hills and valleys and plains, the debt they owe to those surveyors who first laid out the roads and fixed the boundaries so that passage could exist and settlement follow.

The Institute has asked me, as perhaps Archie Bogle’s oldest surviving friend, to give some account of him as I knew him. In honour of his memory, I shall try to comply.

Archibald Hugh Bogle was born at Waipukurau in 1883. His father, James Bogle, who was the railway stationmaster there, was of Scottish stock. James Bogle’s father, Archie’s grandfather,

Page VIII

married Jane Bell, a daughter of James Stanislaus Bell, a Scotsman who was appointed, in 1841, to be British Superintendent on the Mosquito Coast, near Nicaragua. His function was to encourage British trade in the Carribean after the break-up of the Spanish South American empire. There was thus, one may infer, a strain of adventure in Archie’s heredity. This thought is supported by the fact that Jane Bogle’s younger sister, Emelia, married that great adventurer, G. F. von Tempsky who fought so gallantly, and lost his life in the wars against the Maoris. Archie was always proud of the fact that his grandmother’s sister had married von Tempsky. These family connections may help to account for the strong element of adventure in Archie’s own blood and to illustrate the Bogle family motto “spe meliore vehor’’ – I sail on in better hope.

Archie was the eldest of James Bogle’s family, followed by his sister, Dorothy, and his brothers, Gilbert, Gordon and Stafford. The youngest child, Jack, died in childhood.

Archie went to Napier High School with a scholarship. In due course, he passed the Civil Service and University Entrance examinations. In 1900, he joined the Lands and Survey Department at Wellington. In 1902, he attended Victoria University College but he did not attend again until 1906. During the interval, as he tells us in his book, he learned surveying as a cadet, working much in the middle parts of the North Island. With the cheerful, chaffing, happy-go-lucky nature of his youth, he made friends among the Maoris and came to speak their language.

By 1906, he had qualified as a surveyor and was employed by Seaton and Sladden, a leading Wellington firm. He then returned to the University from 1906 to 1910. He never aimed at a degree, but took a few classes in subjects which he wished to study. His brothers, Gilbert, Gordon and Stafford, also came to Victoria. In 1907 and 1908, the four brothers were there together. They all enjoyed the student life and each of them played his part.

At the University, Archie was, as he remained throughout his life, tallish, lean, with a long head, well-defined features and eyes that were merry but often quizzical, as they betokened the making of some bantering or witty comment. Mostly, he seemed to bubble over with good cheer. He was kindly, too, and ready to help any cause that appealed to him. He joined no student religious societies. He was, it seemed, by nature a humanist. His code was “playing the game’’ a code which he observed throughout life.

He was a splendid all-round sportsman. In various years, he represented the college at rugby football, cricket, hockey, tennis and athletics. In some years, we were members of the same hockey, tennis and athletic teams. In 1908 and 1909, he was New Zealand University champion in the 120 and 440 yards hurdles. But his talents were by no means limited to sport. He was an artist with words and had a sparkling pen. He was sub-editor of “The Spike”, the students’ magazine, in 1907 and editor in 1908.

He had a fine tenor voice. With his singing and acting ability, he gave expressive renderings of college songs, written by the great student composers of those days, Siegfried Eichelbaum, Seaforth Mackenzie and Frederick de la Mare. With his brothers as principal assistants, he organised the hakas which he had learned from the Maoris and which enlivened the preliminary proceedings of the Extravaganzas. Dressed and painted realistically, his band of warriors gave thrilling performances, ending with a rush down the aisles of the theatre through an excited audience. As one may imagine, Archie was a very popular student.

At Victoria, he met the lady who was to become his wife. Bertha Langley Reeve came to the University in 1906. She was a woman of strong but engaging character and of high intellect, with a gift for mathematics. Like Archie, she took a prominent part in student life. They were fellow members of the Glee Club. They were married in 1911 and settled in Wanganui, where Archie practised his profession.

VIII

Page IX

When the First World War came in 1914, Archie had wife and child to support, but in September, 1915, his brother, Stafford, was killed at Suvla Bay, on Gallipoli, and Archie wanted what he called ‘‘a crack” at the enemy. So when, about that time, the Chief of the New Zealand General Staff appealed for men with engineering experience to enlist, because the army engineers were short of officers, Archie enlisted. In characteristic style, he wrote to me saying, “I am awa ‘to the killin’, Davie, my lad.”

He saw active service in France with the New Zealand Engineers and also with the Royal Engineers of the British Army. While he was there, his brother, Gilbert, who was a Regimental Medical Officer with the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, was killed on the Somme, in September, 1916, when gallantly attempting to rescue a wounded man. Archie soldiered on. But the horrors of war could not destroy the artistic nature which he combined with so much practical ability. When writing home that the bombardment at Messines in June, 1917, was probably the hottest yet, he could still comment upon the beauty of the vegetation that was left and upon the fact that birds were singing all through the bombardments.

His artistic nature found further expression in verse when the ‘‘Chronicles of the N.Z.E.F.”’ the newspaper for the expeditionary force, held a competition for a New Zealand national song. There were many entries. The judges were the New Zealand High Commissioner in London, Sir Thomas MacKenzie, and that very distinguished New Zealand statesman, writer and poet, William Pember Reeves. They awarded the prize to Lieutenant A.H. Bogle. Here is his poem as it is recorded in ‘‘The Old Clay Patch’’, the Victoria University College book of poetry:

‘Far away yonder across the dark water

Set like a gem on the breast of the sea,

The joy of my heart and the queen of my fancy

New Zealand is calling, aye calling to me.

Others may boast of their cities and temples

Castles and pedigrees, lands wide and fair,

But give us a glimpse of our clean running hilltops

And where is the breath like our own native air.

There is the soil that has formed us and fed us,

Streams that we played by, the warm sky above;

And there are the hands that we clung to as children,

The homes of our dead, and the women we love.

New Zealand! My country! The fount of pure freedom,

Where all who are worthy may bear them like men,

May the Lord give us strength to uphold thee in honour,

And the star of thy destiny never shall wane.’

About the time this poem was written, Archie’s last surviving brother, Gordon, was killed at Ypres, in September, 1917. The loss of all his brothers struck deeply into Archie’s consciousness. There were times long after the war, when he wondered why his family should have suffered so severely, sometimes dwelling on the quenching of the promise of Gilbert, whom he had helped through his medical course. There were also times when he felt a little bitter when he met some prosperous persons who, he thought, might have gone to war but who, for some reason, did not. For the most part, however, he kept these feelings to himself and few would have known he had them.

Page X

After the war, Archie returned to his profession in Wanganui. When the deep economic depression of the 1930’s dried up his work, he and his wife fought back. They left Wanganui, living for a time in a caravan, while Archie took jobs around the country, building small bridges and other small structures. His highly educated wife, in jolly mood, cooked for Archie and his men, some of them Maoris whom they both liked well. Before the Second World War, they settled at Stokes Valley, where Archie was able, in due course, to develop some land at a profit.

During the Second World War, he enlisted again. In 1943, at the age of 60, he went to Tonga to construct defences against possible attack. None was likely. So he applied to be sent to the Middle East where there was fighting. Inevitably, at his age, his application had to be rejected. But the rejecting officer, Brigadier Stewart, who stammered a little, showed his appreciation by saying, “By God!……. Bogle… you are….a bloodthirsty…… old bastard.” In essence, however, Archie was only seeking to do to the full what his loyal and adventurous spirit was telling him to do.

After the Second World War, he returned again to the activities of his profession and the work of the New Zealand Institute of Surveyors. As part of that work, he took a large share in the initiation of the proposal for the establishment of surveying as a University discipline and in pressing for its approval. As Chancellor of the University of New Zealand at the time, I was well aware of this development and supported it. The project has been successfully accomplished at the University of Otago.

Archie’s wife died in 1946. For over a quarter of a century since then, he had the support and affection of his family. Each of his two sons became a Rhodes Scholar and a University professor, a very special distinction for one family. His elder daughter is a Home Science graduate, and his younger daughter was the top Social Science student of her year. This is a record of achievement of which he must have been deeply proud, but he was not the kind of man to say much about it.

In his last years, he came to live in Wellington. He practised his profession to the extent that it suited him. We used to meet, at times at the dinner table, and we went to some symphony concerts. He liked music, especially if it were bright and gay but he positively disliked the garish noises that sometimes pass for music today. For his eightieth birthday, the Institute gave a dinner in his honour and I had the pleasure of being a guest.

About the middle of 1969, when his health had deteriorated so that he could no longer properly manage his flat, he went to Auckland to stay with his younger daughter and her family. In January, 1970, he went to Rarotonga to stay with his elder daughter, whose husband, then retired from the New Zealand Works Department, was assisting the Cook Islands Government. But Archie disliked the heat and was glad to be back in Auckland in March. He stayed there, receiving hospital treatment when required, until his death two years later.

Archie Bogle was an exceptionally gifted man. His experience of life made him search for reality. He sometimes contemplated other people with a reserved slightly smiling, interrogating look to see if he found it. He did not tolerate humbug or dithering. He had courage in abundance and said what he thought. The qualities of honesty, desire for fair play, wide-ranging ability, capacity for hard work and determination, combined with an innate hankering for the team spirit and co-operation, showed naturally in all his activities and attitudes. He had his sombre times but he was rarely, if ever, without the capacity for racy speech. A quip causing laughter could break a deadlock in debate. According to the occasion, he could be consistently serious, gay, witty or humorous. His own chuckle and laughter remain clearly in mind. To me, he seemed to evoke affection, quite unconsciously. He has left behind him a lasting and lovable memory for his family, friends and colleagues and, through his work, a permanent contribution to the welfare of New Zealand.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.