18 HISTORIC PLACES: June 1984

the air. World War I had begun to break down the barriers of class and poverty and women had become used to working. Their liberation from the home was accompanied by a revolution in dress. This freedom was fuelled by other factors. The motor car provided mobility and speed. The cinema gave people in isolated backwaters a glimpse of life as it was lived in the wide world. Mass production and new inventions made it clear that the twentieth century was a new era, unlike any before. And in many countries, particularly the United States, the 1920s were years of prosperity. It all added up to a frenzied decade in which vulgarity, exhibitionism and effrontery became respectable.

The Art Deco style matched this spirit. Its lines were angular and frenetic and the motifs which were used repeatedly reflected the new freedom – sunbursts, leaping animals and women, lightning flashes and symbols of power, speed and flight. Perhaps the most characteristic shape was the ziggurat or stepped pyramid, adapted into many variations but used particularly in buildings, for it suited perfectly the outline required by the zoning laws introduced in America in 1916. These required buildings to be stepped back as their height increased to allow light into the streets.

The reign of the style can be divided into two distinct phases, the 1920s and the 1930s, separated by the Wall Street Crash, though with a gradual transition. Each phase reflects the spirit of its decade. During the 1920s, decoration was ornate (friezes, monumental entrances, complex relief panels), materials were exotic (rare woods, metals and leathers, ivory, enamel and sharkskin) and colours rich (red, purple, amber, gold, orange and brown). In the later phase, decoration was sparse and simple (circles and straight lines), materials were more prosaic (steel, chrome, glass, mirror and painted wood) and the colours cool (black, white, cream, green and silver). This phase is sometimes considered to be a different style altogether, ‘Streamline Moderne’.

The 1930s period showed the influence of the Bauhaus School of Design, founded in Germany in 1919. Its concern with the provision of an adequate standard of living was in line with the politics of the 1930s and its simplicity suited the shortage of money. Its disciples preached that all decoration was abhorrent, and that everything created by man except pure art should be rationally functional. It was hard for the public to take and the popular response was to decorate the plain surfaces, in a simpler way than before, but still with Art Deco motifs. Rounded edges and corners and cylindrical forms were also used.

In 1929, the building boom of the 1920s was brought to a sudden end by the Wall Street Crash. Buildings already underway, including that symbol of the 20th Century, the Empire State Building in New York, were completed, but very few were begun. At that time, Art Deco was in full flower as the favoured style in public buildings in the world’s major cities. But the slump prevented the style from spreading to smaller cities.

On 3 February 1931 an earthquake of magnitude Richter 7.9 struck Hawke’s Bay. Hastings suffered severe damage, with many masonry and brick buildings destroyed. In Napier, which had fewer wooden buildings in its centre, the destruction was greater. In addition, almost complete disruption of the water supply prevented the fighting of the fires which broke out. Twenty-four hours after the earthquake struck, the centre of Napier had been wiped out. Most of the few buildings which still stood were gutted by fire. 258 people had lost their lives and many more were injured. Property damage, in 1931 values, amounted to $7.5 million.

To those who were not in Hawke’s Bay at the time, no photograph or story can convey the reality of that disaster. It seems impossible, standing in the streets of Napier or Hastings today, that here were scenes of fire, death and destruction.

The Hawke’s Bay Earthquake Bill provided funds for the reconstruction of damaged buildings and services and for three years Napier and Hastings resounded to the noise of builders at work. New towns were built at a time when the World was not building.

The architects practising in Napier at the time – C.T. Natusch and Sons, Finch and Westerholme, J.A. Louis Hay and E.A. Williams – co-operated as the Napier Combined Architects. In Hastings, Davies, Garnett & Phillips were practising. The workload was enormous, for many buildings required inspection and reports before demolition or strengthening was carried out. In some offices, staff worked in shifts to complete working drawings for builders. Some buildings, such as bank premises, were designed by architects in other centres.

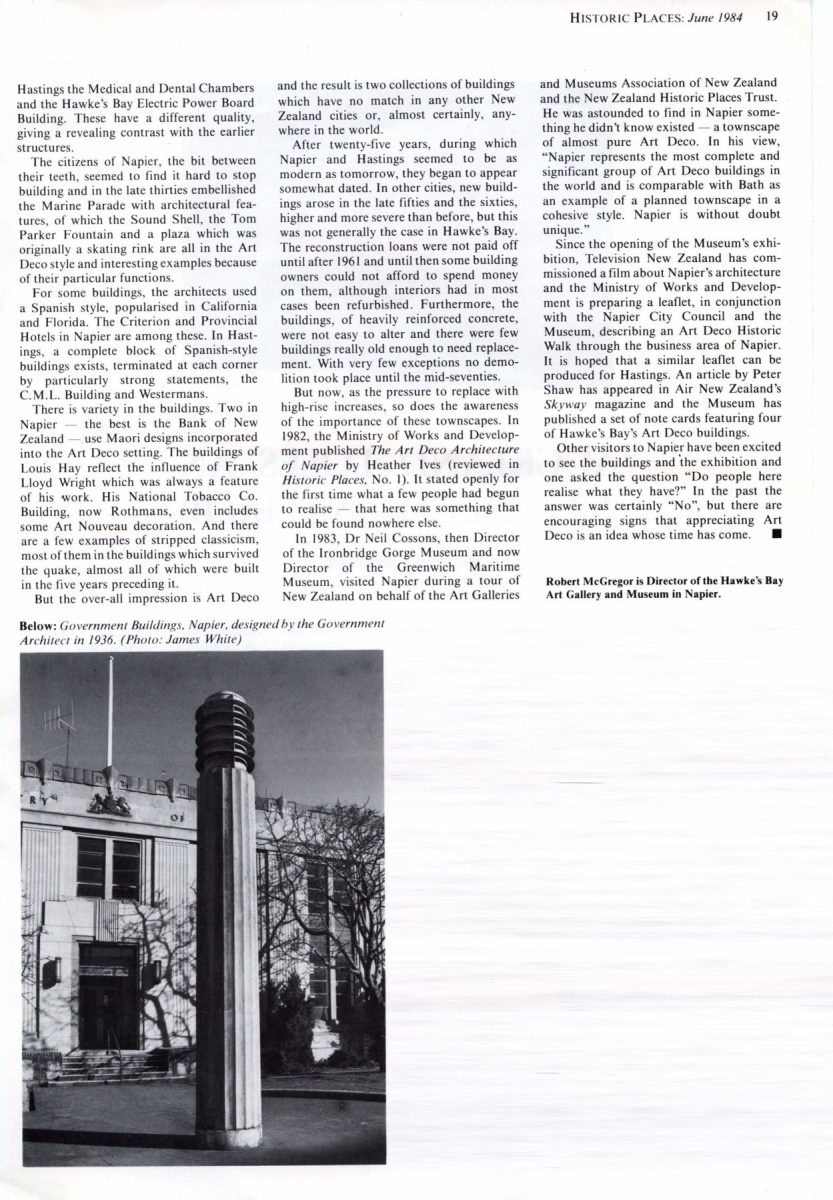

Although buildings in the area which had been erected just prior to the earthquake showed no Art Deco influence, a majority of the new ones did. Many of the new buildings were simple, low-cost premises for businesses which had suffered financially in the earthquake, but they all exhibit some form of decoration, at the very least a plaster frieze or emblem. The best of them are irreplaceable examples of the style which could not be duplicated today. In Napier, the Daily Telegraph, the A.M.P., Masson House, Rothmans and the Central Hotel are all fine examples and their neighbours, though less distinguished, provide a good foil for them. Later in the decade, the Ministry of Works, the Municipal Theatre and the T. &. G. Building arose and in

Photo captions –

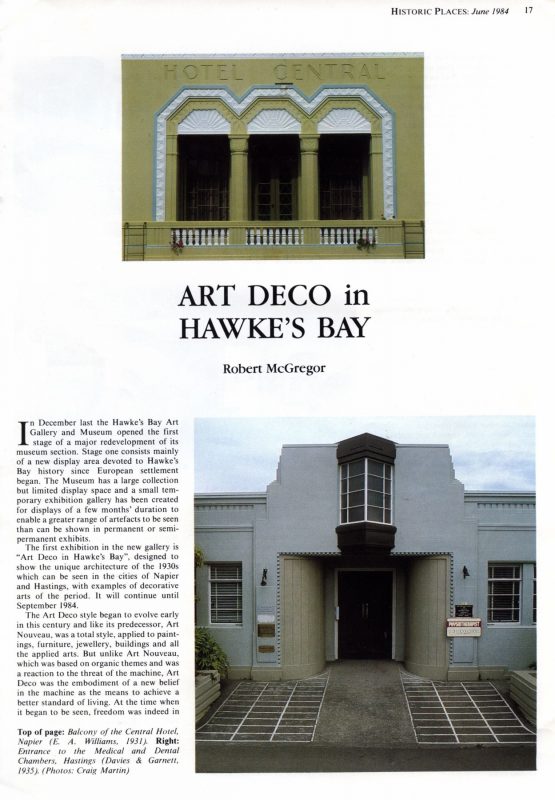

Above: Hastings Street, Napier, in 1933. The view today is unchanged. (Photo: Hawke’s Bay Museum)

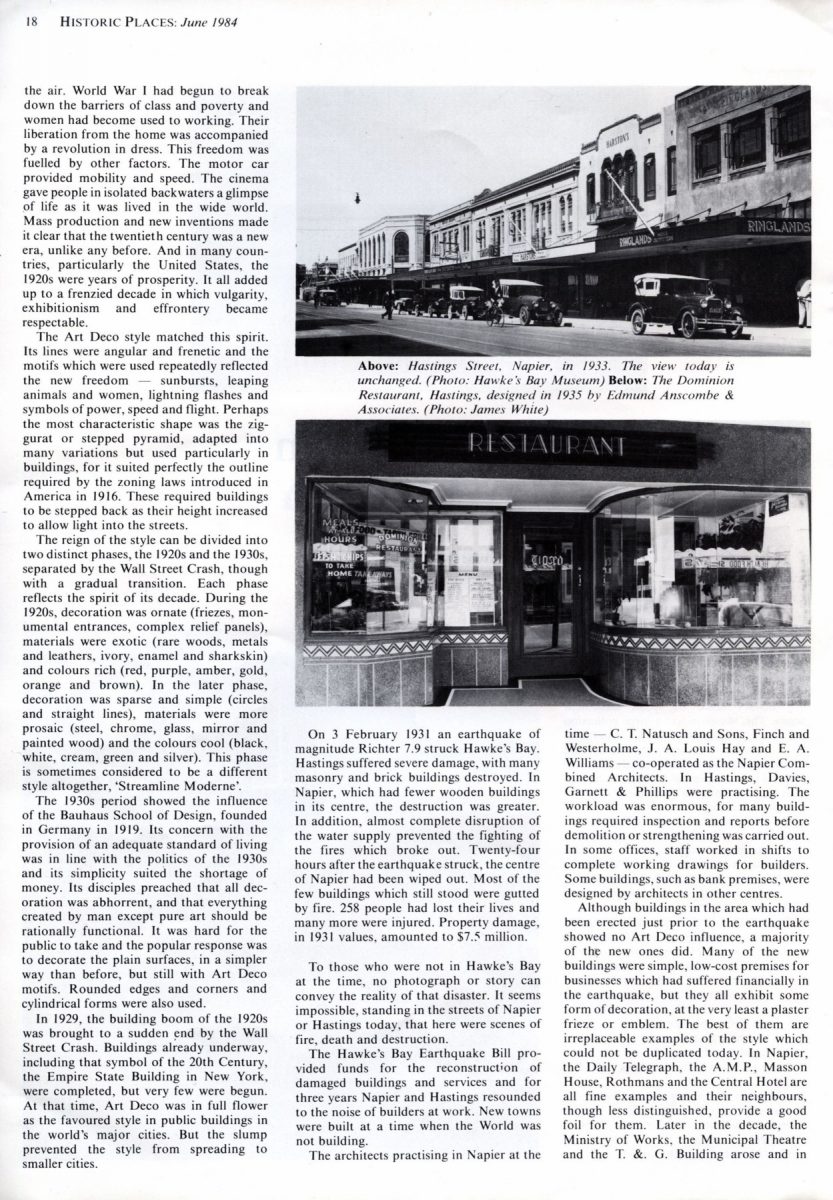

Below: The Dominion Restaurant, Hastings, designed in 1935 by Edmund Anscombe & Associates. (Photo: James White)

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.