9

an Idiom

ARCHITECT John Scott’s professional life was unconventional, his unorthodox approach to architectural education and practice often cited as the basis for his brilliance as a designer. He was born in 1924 at Haumoana in the Hawkes Bay, and was of Taranaki, Te Arawa and British heritage. He enrolled at the Auckland University College School of Architecture in 1946, after training in the Air Force in the last year of World War II. Before that he worked for a short time as a shepherd. While he found inspiration and mentorship in the company of staff such as Vernon Brown and Bill Wilson, university life did not suit him, and he left the school a few papers short of completing his diploma, eventually finding short-term employment with R. Pickmere Architect, Structural Developments and the highly innovative Group Architects. Hankering for the nurturing environment and intellectual freedoms of small-town life, he returned to Haumoana in 1953 with his expanding family and started his own practice.

From the beginning, private residences dominated his work, punctuated by some exceptional public commissions. The architectural historian Russell Walden describes two early projects, the Savage and the Falls houses (Havelock North 1952-3), as examples of a nascent design philosophy that drew on the whare (Maori house) and woolshed as vernacular design precedents.

From these concept generators come the hallmarks of Scott’s residential designs: porches, strong roof lines, “honest” materials, such as exposed timber and unpainted concrete, and carefully placed glazing.

In a 1991 interview about the house he designed for his daughter, Ema, and her husband on the family landholding, Scott explained that his convention of arranging major sections of the house around the main entrance was derived from the pare (door lintel) of a meeting house. In Maori architecture, the pare is a ritual transition marker between the inside and outside that also sets up a division of function down the house. The pare’s carved female form, usually Hinenuitepo – a deity who is the gatekeeper to the realms of life and death – held a special significance for Scott, who regarded entrances as important places of welcome and departure.

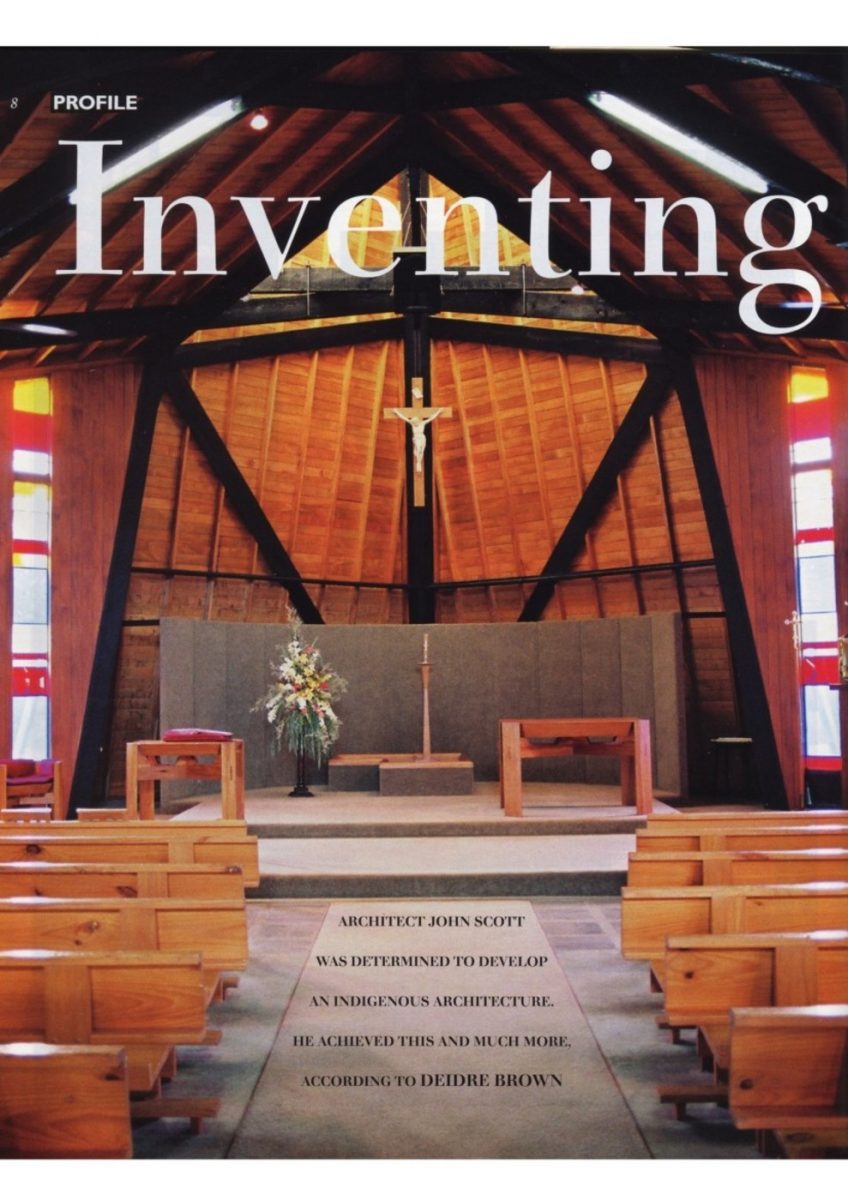

An early public triumph was St John’s Chapel in Hastings (1954-6), which attracted the offer of the project for which he is best remembered, the Chapel of Futuna, Karori, Wellington (1958- 61). Walden has described it as a fusion of Maori and Christian architecture. Its ribbed rafters, central “heart” column and low eaves are reminiscent of the anthropomorphic structure of a Maori meeting house, while its overall form was clearly influenced by Le Corbusier’s celebrated Notre Dame du Haut, completed in 1955 in Ronchamp, France.

Artist Jim Allen designed Futuna’s stained-glass windows, which are also reminiscent of those in Notre Dame du Haut and Henri Matisse’s 1951 decoration of the Dominican Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, near, Nice. Futuna’s Maori references not only locate the building here, in Polynesia, but also recall the Pacific Island of Futuna on which the missionary Peter Chanel, to whom the project is dedicated, was martyred in 1841. Futuna Chapel, as it is widely known, is generally regarded as one of New Zealand’s finest buildings, winning the New Zealand Institute of Architects gold medal in 1968 and its 25-year Award in 1986.

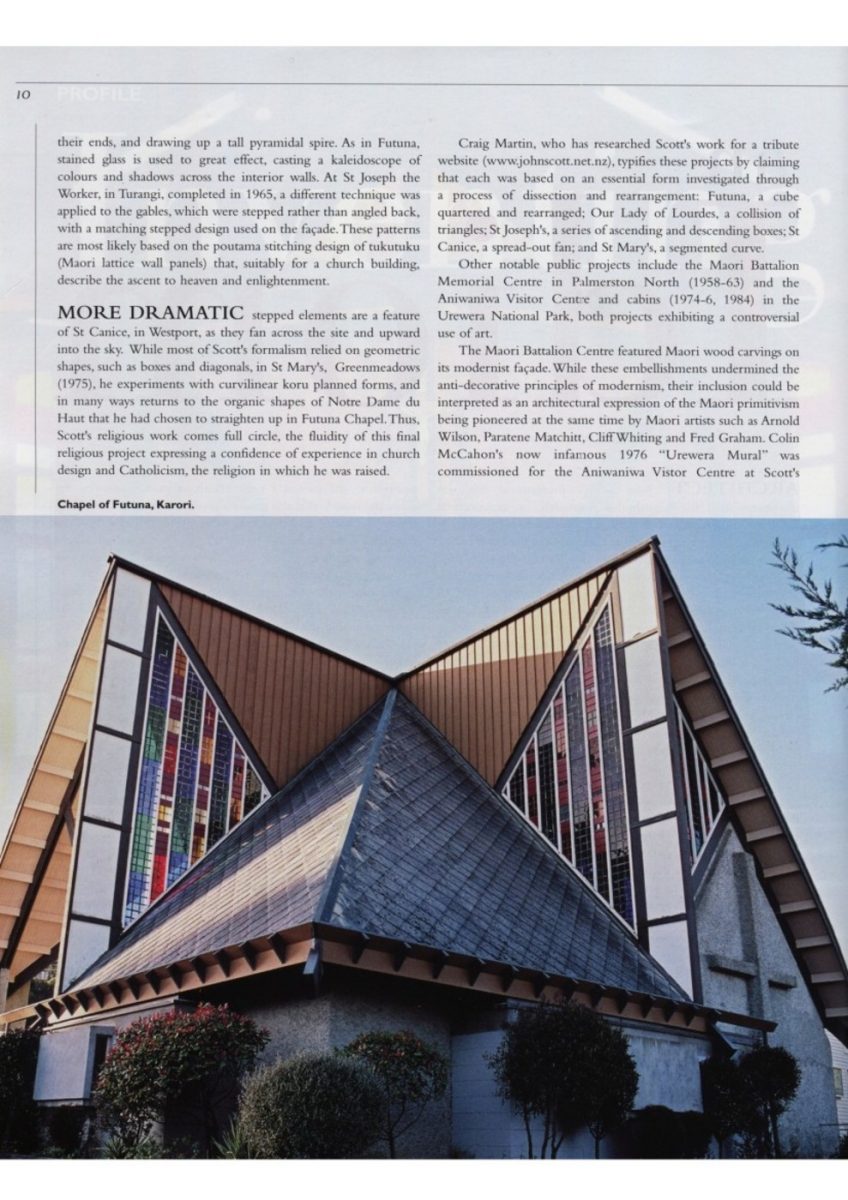

The success of Futuna led to a number of other church commissions, each of which developed forms and concepts from earlier projects.

For Our Lady of Lourdes, built in Havelock North in 1959, Scott extruded the roof line first seen in Futuna, exaggerating the gables by pulling back

Photo captions –

LEFT: Interior of Our Lady of Lourdes, Havelock North.

ABOVE: John Scott

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.