which was kind of them – it was 3pm.

They must have rung Arnhem to say they had a prisoner and then the pilot who shot me down came over. He told me later on that he wasn’t supposed to go – the Political Officer on the station told him he wasn’t to, but he was a leading ace – 50 destroyed (48 until that day) and he said: ‘I’ve just shot him down and I’m going over to see what he looks like.’

Can you remember meeting him?

Oh yes. I saw this car arrive and I thought somebody was going to collect me. There were four in the car and there was no room for anyone extra. I saw him coming across the small bridge of the small canal that was near the hut, and there was a knock on the door and I said ‘Come in’. And in he came and stood there and saluted, and I stood up and acknowledged it – with some difficulty and pain. And he said: ‘Were you flying the Spitfire?’ And I said ‘Yes.’ And he said: ‘Well, I was flying the other.’ He spoke in English. Understandable English, with a little bit of sign language. And then he said: ‘Do you mind having some photographs taken?’ And he asked when the invasion was (it was six weeks before the invasion) and I said: ‘Well, Churchill hasn’t told me, and if he had I wouldn’t be telling you …’And he said: ‘I shouldn’t have asked…’ That was the tone of the discussion.

I said: ‘Well you haven’t got a show …’ and in his letter 26 years later he said ‘… you said we couldn’t win.’

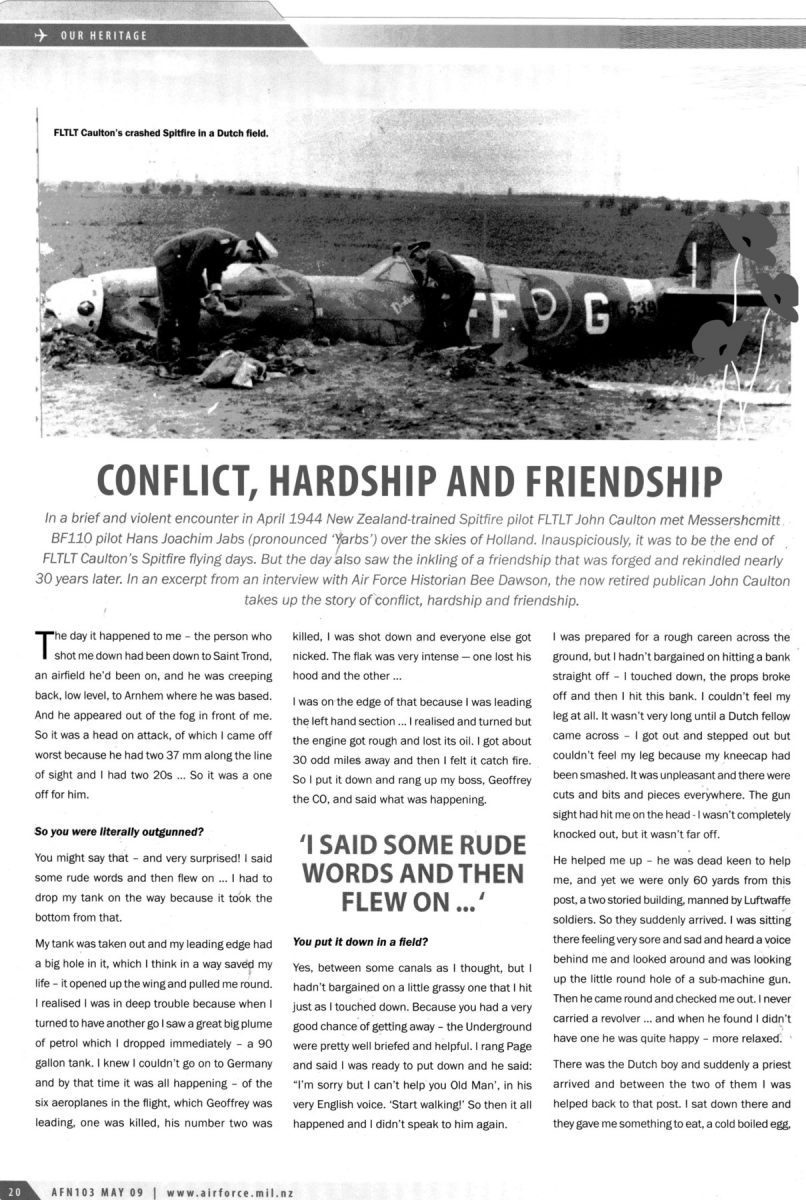

Anyway, then they went down and had a look at the aeroplane where those pictures were taken and they went off.

Then came along another car with two rather evil looking people. They were field security police – they had a chain around their neck with this big oval plate with ‘Field Security Police’ on it… It’s a very lonely feeling when you’re in a country where nobody wants to talk to you. They said nothing but motioned to me to get into the car into the back seat with my parachute. It was a lift up seat and he put it down on my foot which made me gulp with pain, so I pushed it forward and he didn’t say anything – he just turned round slowly and looked at me which I thought was an indication to me to shut up! Then they took me to Arnhem Camp – 30 off miles away and l was just put into a cell on my own.

You’d have been pretty scared…

Not at that stage – in the car I was a bit worried, concerned about saying the wrong thing, but then I was put into solitary. There was a wooden bench and a stool, and for the life of me I couldn’t get up onto the bench to lie down. I noticed that the stool was about six inches lower so with a lot of grimacing I got up onto this and lay down – with a lot of grunts and groans.

Then this little man, a sergeant major I suppose, kept on screaming at me – they scream an awful lot, particularly when they’ve got a gun. You don’t know what’s going to happen next because you don’t understand the language.

So he pushed me into the cells and after a long time I lay down on the bench. I hadn’t been there for half an hour when he came in screaming again: ‘Aus!’ With a lot of agony I got off the thing and was taken to an absolutely identical cell – one stool and one bench, nothing else. I called him a few names, but he didn’t understand them. I thought I had it set – so I put the stool against the bench and got up on the stool with my good leg and as I went to step across the stool went – it slid from behind me and I ended up against the wall with a thud …

And this character rushed in and he completely changed from being an arrogant little … and went to help me up, but I wouldn’t allow him and took a swipe at him because he’d been the cause of it by making me change rooms. And I missed him but he went out and left the door open and brought two prisoners out of another cell and they lifted me up. And I was taken to another room again where I had a bed with a kapok mattress on it! I was laid on this and then he sent for the doctor. Then he kept coming to see how I was.

The doctor came in with a field pack and put an aluminium splint on the leg which was a damned nuisance really – walking with a splint with no crutch. And he gave me an injection with the biggest needle I’d ever seen. I thought it was going to hit the bone and break off – it was like a 3″ nail. He told me to pull my tweeds down and he threw it like a dart. It was for tetanus.

The next day we were taken away in a bus – a whole bus full of us – up to Amsterdam and we were locked up there for about ten days, until they’d gathered enough for a trainload.

You weren’t with the Gestapo at this time?

No, they’d all disappeared. We were with Luftwaffe soldiers. The Luftwaffe were under obligation to keep their own prisoners. I was lucky to have them from the word go.

John Caulton spent almost exactly a year as a POW before returning to England, marrying his English bride and returning to the Hawkes Bay in New Zealand.

In the 1960s he read a book by a Luftwaffe ace Hans Joachim Jabs. His daughter, then travelling in Germany managed to track down the former ace. Caulton wrote, and in 1972 the pair met during a trip to Europe. It was a ‘liquid occasion’ with old time memories and reminiscences cementing the new friendship. In 1975 he visited the field where he was shot down and met the Dutch farm worker who had saved him. Caulton and Jabs continued to meet regularly until Jabs passed away in 2005.

Photo caption – Hans Joachim Jabs (left) and FLTLT John Caulton photographed soon after his Spitfire crash landing. Courtesy of the Caulton family private collection.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.