- Home

- Collections

- OLIVER DJ

- Making a Difference

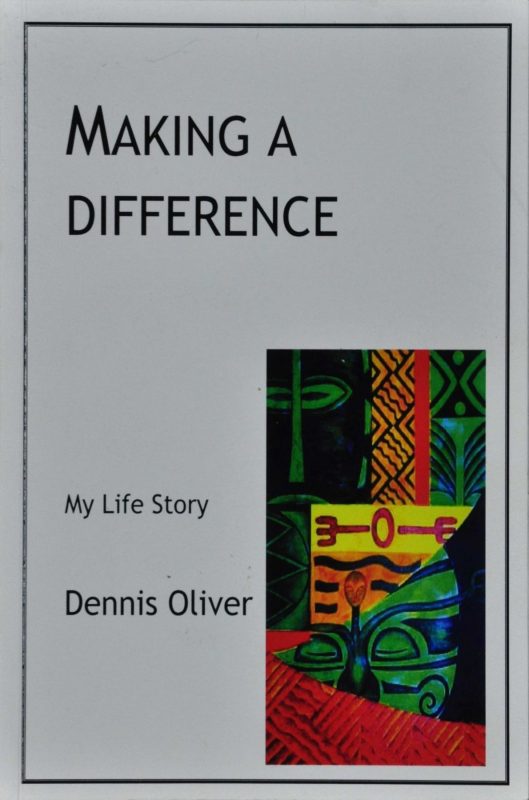

Making a Difference

PREFACE

I originally wrote this book for the family, particularly for Robert, Richard and Shelley. However, since putting it to print I have realized that some of it might be of interest to others, in particular the way we grew the YMCA in New Plymouth from small and homeless to big, housed and thriving ; the bits about the shoeshine boys story and the Rural Work in Fiji; the campaign to reduce the suicide rate in Samoa, at that time the highest in the world; the innovative programmes in Samoa and the wide range of programmes we invented in Hastings to help unemployed people find their way into the job market.

I have included Chapter ten, ‘A Purveyor of ideas’ particularly for those readers who use the Community Development process in their work.

It has been my privilege to have indirectly touched on the lives of thousands of people in New Zealand, Fiji and Samoa through many absolutely wonderful staff of the YMCA’s there. They are too numerous to name but I would guess that they are still exercising their wonderful talents in their current spheres of influence.

I have titled it “Making a difference” because that’s the mission my mother encouraged me to pursue over seventy years ago and I am still working on it. Since I finished writing it in 2007 a couple of events have made highlights; In 2010, the book my son Robert wrote, “Me’a Kai – the food and flavours of the South Pacific”, at the Gourmand book award won the title, THE BEST COOKBOOK IN THE WORLD. A lot of the credit goes to my wife Jean and is a positive reflection of our families time in Fiji. Then in March 2012 l was the recipient of the DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI SERVICE AWARD by Massey University at a grand reception in Wellington.

I must acknowledge the artistic merit of my nephew Jeff Lockhart who designed the Pacific motif on the front cover.

It still remains my personal life story and I have to say, I have achieved nothing by myself. I have helped others organize and tackle stuff that has helped us all grow and develop.

It has been one adventure after another shared with the family team, and it carries on even now. Retirement from full-time paid employment presents lots of opportunities for community work. And that adds satisfaction and fulfillment to one’s life.

Dennis Oliver

Contents page

Chapter One Growing Up in Hawera 1

Chapter Two Enter the New Plymouth YMCA 22

Chapter Three Expanding My Professional Self 38

Chapter Four The Fijian Adventure 48

Chapter Five Back in New Zealand….briefly 81

Chapter Six Adventures in Samoa 86

Chapter Seven Inventing Community Management Ass’ 112

Chapter Eight Back Home to Hastings New Zealand 123

Chapter Nine And so to Retirement 159

Chapter Ten A Purveyor of ideas 177

Page 1

Chapter One Growing up in Hawera

I was born in Wanganui, New Zealand on August 13th 1932. My father had emigrated from Cornwall having served his time as a grocery assistant at the Co-op in St. Dennis. The family’s home was in the village of Indian Queens, not far from Newquay. Dad was the eldest in the family of two boys and five girls. His cousin Harry, had emigrated to New Zealand and in 1924 wrote to dad encouraging him to make New Zealand his new country. He said, “The wages in your line runs from four pound ten shillings a week, and board one pound ten shillings a week. Hours of work quarter past eight in the morning until half past five and one o’clock on Wednesdays, nine o’clock on Saturday nights. A fortnights holiday in a year on full pay. I’ll tell you this, if you stayed out here for three years you would never want to stay home (Cornwall) any more. Now you must please yourself, you won’t pick up gold in the street and you’ll get hard knocks and wish yourself home, but you must have courage and fight and you will win as I have done. Fifteen years ago I landed in New Zealand without a friend in the world and thirty shillings in my pocket. I did all sorts of jobs. Now I am on my feet. I was a carter in a timber yard twelve years ago; l went to stacker, tally clerk, foreman, now travelling the country on orders with a motor bike at five pound ten shillings a week. I also own my own home worth six hundred and fifty pound and keep 500 fowls and can hatch one thousand eggs at a time . . . Now Will, I hope things are clear to you. I am not going to advise you my way, it’s up to you. This country wants men, and you and your friends would get on alright provided you stick…” This was sufficient encouragement for dad, so he come, and he stick.

When he arrived in New Zealand he got a job with Maypole Stores, Wanganui, owned by the Gilbert family. My sister Laureen was born two years earlier than me. My mother was called Joyce, her maiden name was Irene Joyce Gilling. She was brought up at one stage at Matapu, Taranaki, and her father was a beekeeper and wrote one of the first books about beekeeping in New Zealand. He drowned at Kawhia when Mum was pregnant with Laureen. My mother’s mother was Janie Trerise. If one journeys to Cornwall and visits Trerise Manor, the line of family going back to around the fourteenth century shows a Janie Trerise about every third generation. I cannot however, claim a direct line there. But wait!! There is the

Page 2

possibility that maybe, according to an ancient letter written by my aunt that the Trerises of Trerise Manor…but perhaps that is speculation. ??

All of this background demonstrates why I describe myself as “an indigenous Pakeha with a Samoan Chiefs title (more of that later) and Cornish blood.”

When I was two years old in January 1935, Dad took Mum, Laureen and me back to Cornwall to meet the family. These were the years of the Great Depression but the young grocer saved money by living for two years on broken biscuits, bruised fruit, dented tins and any other scraps the grocer shop threw up. At the same time, Mum earned fifty pound by taking wooden bowls, doing pokerwork designs on them, a touch of paint, a coat of varnish and selling them from door to door. We travelled from Wanganui to Auckland by train to catch the ship and apparently at every station the train stopped I asked, “Is this England?” We left Auckland on January 25th 1935 on the good ship “S.S. Ormonde” taking seven weeks to get to England. On the journey, at the port of Aden, Mum’s diary said “Dennis insisted on calling the camels ha-ha gee gees.” When the ship went through very rough weather Mum’s diary reports on the fall of the sick one by one until “Only Dennis went to dinner and ate the lot like a real little man.” A couple of stories have been passed down from the five months in Cornwall. The family took Dad aside and said “You got to stop Joyce braggin. We don’t approve her braggin.” Dad enquired,” What she braggin about?” “When we ask ‘er, ‘ow ‘arre ye Joyce? , she says ,”Good. ” Not up to ‘er to say she’s good. So Dad drilled Mum that when she was asked ‘ow arre ye, the correct response was, “proper thankee.” My dad’s family had a little farm and had a few cows to supply the Cornish cream which they sold in the village. Apparently one time I wandered into the house with cow manure up my leg having been down at the cow shed. When they asked, ‘Where’s your gumboots?” my reply was, “in the moobuck.”

On August 22nd we sailed from London on ‘S.S. Remuera’ via the Panama Canal arriving in Auckland on September 28th 1935. l have no actual memories of this Cornish experience, but when l next travelled to Cornwall in 1987 aged 55, the lilting Cornish brogue became second nature as quick as taking the next breath.

When I was five, we moved to Hawera which was to be my ‘home’ for all my boyhood years. At that time, whilst Dad was still with Maypole stores Wanganui, a group of grocery stores came on the market and the Gilbert family suggested to Dad

Page 3

a business proposition. The upshot was that the struggling Cut Rate stores with seven shops were bought out and made into Maypole Stores (Taranaki Ltd.) with Dad as Managing Director and with the financial backing of Maypole Stores Wanganui, and A. S. Patterson, grocery wholesalers. The deal was that Dad would earn his shares as they were converted from dividends each year. The firm was expanded to thirteen shops in Hawera, Eltham, Patea, Manaia, Stratford, Inglewood and New Plymouth.

All my schooling was done at Hawera Primary School and Hawera High School. I have few memories of school life. The last rugby game I played I was around eight years of age. The school bully who was twice the size of any other kid was squashing all and sundry as he made a feast of tries. I attempted at being the hero by throwing myself at his legs only to get my face kicked as I landed in the mud. I went home bawling my eyes out and haven’t played rugby since. I learnt by experience that I don’t like getting my face kicked so therefore avoid those situations where it is considered legal and manly. At High School I took up hockey and played in the school’s second eleven. In Standard Five, I had a succession of five teachers through the year and gained the impression us kids were just a factory job lot. I think at that stage I went from better than average to that meaningless report card, “Could do better.” I did well at High School in english, mathematics, wordwork [woodwork] and physical education. I have no idea why they tried to teach us history, geography, social studies or science and there was little or no attempt to make it relevant to us. I think I had four good teachers over four years and several that should have never been let loose on the human race as guides and mentors. I sat School Certificate in 1948, the year of the polio epidemic when schools had been closed for twelve weeks prior to the exams. I failed School ‘C’ by two marks. These were the years when School ‘C’ was structured so that fifty percent had to fail. I sat again in 1949 thinking I would cruise through with very little effort. However, apparently everyone else tried a bit harder and I failed by two marks again. I attended the Hawera High School centennial reunion with the sole intent of finding the gym teacher who always said “Good work Oliver”, the only teacher I remember saying that to me. I went on to make a career out of that.

I left school and joined that staff of Maypole Stores. I worked at the main shop in Hawera for a year while it was in the process of becoming the first self-service store

Page 4

in New Zealand. I did a six month spell on the rural delivery truck and managed to get stuck on a wide variety of back country farms in an assortment of muddy situations. I was the bulk store man for a few months and learnt how to stack 180 pound sacks of wheat three high and 200 pound sacks of washing soda four high. There was a skill in taking a 180 pound sack of wheat on your shoulder, carry it twenty yards and tip it into a forty gallon drum.

I worked in number three Maypole for three years with a character of a boss. We were next to the White Hart Hotel and some of our customers came straight out of the pub into our shop. These were the days when shops opened at 8:30am Monday to Friday and closed at 5pm Monday to Thursday and 8:30pm on Fridays. Nobody opened Saturdays and Sundays. Service was Mrs Jones asking the grocer over the counter for a pound of butter resulting in grocer darting to the fridge, getting a pound of butter and placing it on the counter. Many customers telephoned their order to the shop which was delivered the same day by the boy on the bike. Sometimes after school l was the boy on the bike. Customers ran up accounts on credit which were paid off on the 20th of the following month. Farming families accounts were frequently in the hundreds of pounds monthly. All the dockets were added up without a calculator in front of the customer. Payment was made by cheque or cash, real money, pounds, shillings, and pence. Plastic credit cards had not yet been invented. Change was counted back into the customer’s hand. There were no plastic bags. There were brown paper bags and parcels were tied up with string, not cellotape. I still have parcel and string skills and can add columns of figures. I overcame a lot of shyness and after a time enjoyed meeting people, having a bit of a chat and giving them friendly personal service. This was my first association with Maori. Two old Maori ladies came in every Thursday, sometimes after imbibing next door and enjoyed being served by the big-boss’s-boy. In my last year with Maypole, I worked in Patea, Manaia, and Eltham in relieving positions. I remember being the relieving manager in Eltham while the manager took his annual leave. I think every bad debtor in town came in to try it on but I don’t recall being caught out. Although it was early in the process, there was a feeling l was being groomed to eventually take over Dad’s position as Managing Director. Such was not to be.

During my years of working for Maypole Stores, my mother and I honoured a contract we had made when I first started work. She asked me what my friends were

Page 5

paying their mothers for rent now that they were earning. I asked around and reported to Mum that most were paying three pounds a week. She said that if I saved half of my weekly wage into a special account until I was married, she would only charge me two pounds a week rent. If however, I saved three quarters of my weekly wage, she would only charge me one pound a week. For six years from age 18 to 24, I saved three quarters of my weekly wage so that when I married I had one thousand pound in the bank. This was more than the average annual wage of the time which was about eight hundred pounds.

Hawera was a good town for a young boy to grow up in. it was small enough to be familiar, with a host of community organizations to be involved in, and plenty of civic amenities for a growing lad to enjoy. Next to Maypole Main Shop was the local cinema, The Grand, locally known as ‘The Bug House” The weekly serials included The Lone Ranger, The Phantom, Buck Rogers, Gene Autrey [Autry], but my outright favourite was Tarzan. Johnny Weissmuller was my number one hero. Most times I managed to get into the pictures without paying. Sometimes, I would go around to the back of the pub, pick up a crate of empty beer bottles, take them around the front and sell them their own bottles. On other occasions, depending on what was showing in the first half, I would wait outside the cinema, mix around with the half time crowd, then a couple of minutes after most patrons had gone back in, go into the darkened cinema, find an empty seat and sit in it. Sometimes late patrons would come, stagger around in the dark, make a bit of a rumpus trying to find their seat which had mysteriously disappeared and get thrown out for their disturbance. Pity that. This sort of game was always done in the company of another mischievous companion.

There were a few places just out of town that were good for a game or two. I remember going down opposite Turuturu-mokai where there was a bit of a pond. Jock and David and I had a right royal swim only to emerge with black stuff all over parts of our bodies, including some private parts. l got told off a treat by my Mum for getting tar all over everything. She scrubbed away at my body with Brasso which was renowned as an excellent tar remover. l was lucky to retain my emerging manhood. They certainly shone well.

Another time, Jock and Dave and I sped around Turuturu-mokai on our bikes and sped over a narrow plank over a stream. You didn’t dare get the wobbles or you would end up in the drink. Which is exactly what Dave did, and it was only after

Page 6

watching him for a couple of minutes, Jock and I realized that being upside down under water with a bicycle on top of you wasn’t healthy for survival. So eventually we dragged him out half drowned, full of mud and a bit wiser. These were learning experiences only gained by the adventurous.

The war years, 1939 to 1945, were significant during my boyhood years. The evening news on 2YA was the day’s important event. For one long period, the news was grim with heavy casualties amongst the Allies, and the seemingly unstoppable advance of the German war machine. There was a heavy air of doom in all community events and a pall over the spirit of our home town. Everybody had a relative on active service. Dad was not drafted into the army but was placed in the EPS, the Emergency Provisionery Service. It amounted to being prepared to deliver stores to the Home Guard or the Army or other special services in the case of an emergency.

Dad’s brother, uncle John, had emigrated to New Zealand and was posted to Fiji to teach the Fijians how to drive army trucks. The designer of the trucks hadn’t taken into account the size of Fijians feet which could engage the brake and accelerator at the same time. Some considered John’s job more dangerous than many at the front line.

Most families had their life impacted more than ours because of rationing, but the life of the grocer gave us the opportunity to use the unused ration coupons of others. Every family had a book of ration coupons for tea, sugar, butter, petrol and other items. On the purchase of any of these products, as well as paying money, one had to surrender the appropriate number of coupons. When they were used up, tough, no more until the next ration book was received.

I spent a lot of time playing commando games. Camies home had a bit of bush, a bit of swamp in the bush, and a small lake. We made some bombs that were fairly dangerous. One of them was made with a shell casing, a filling of gunpowder mixture, and half a dozen .22 bullets for good measure. We made a hole in a small bank, packed our bomb in it, lit the fuse and ducked for cover. It’s a wonder the boom didn’t alert the police. We didn’t do another that dangerous as the .22s that went whistling through the air gave us a bit of a fright. Camies older brother was not to be trusted. He invited us to have a row in his tin tub on the duck pond and when we were in mid lake, fired 22s into one end of the tub until it started to sink. The lake wasn’t very deep so we got out and left him to deal with the tub.

Page 7

Another of the consequences of the war period, were some special activities available. “Veges For Victory” was a major thrust. Dad always had a wonderful vegetable garden. There were large commercial vegetable gardens on the edge of town. One offered half-a-crown a sugar bag (about twice a pillow cover) for pickers to pick pea pods. Eat as many as you like. I biked to the farm and ate about the first sugar bag, then picked a sugar bag by which time I felt a bit crook with gas building up so collected my money and biked home. By the time I got home, I was a dangerous item with buildup of a lethal gas. Mum had a meeting of the Methodist Women’s Fellowship in our house and my farting was so persistent and powerful, I wasn’t allowed in the house until later in the day. A cool drink and a stern lecture were brought out to me at the far end of the back yard.

I dressed up as a commando for the Victory in Europe parade in May 1945. It was a big event with every imaginable community group marching down High Street behind the Hawera Band making every noise that they could all conjure up.

Our family frequently had camping holidays. We camped during summers at Nelson, Golden Bay, Napier and the Bay of Islands, Northland. We also visited Mum’s sister Dee and husband Fred at Pirihaka, Whakatane and Ohope beach. What a piece of paradise Ohope beach is.

We also as a family worshiped at the Hawera Methodist Church. Dad was a lay preacher and sang as a bass in the choir. Mum sang as a contralto in the choir while Laureen and I attended bible class and Sunday school.

The clarinettist

Two of the acknowledged community strengths in Hawera were its music and its drama societies. Much of the strength of music in Hawera lay in the leadership of H. C. A. Fox Esquire. He was the conductor of the Hawera Brass Band and the Hawera Orchestra. The Hawera Brass Band was highly respected at national brass band events and on one occasion in the 1940s took the top prize in the national championships. For ten years, from age eight to eighteen, l attended weekly clarinet lessons under the tutelage of H.C.A. Fox. He was not a cuddly man. He had a firm persona, a waxed twirly moustache, a slicked down hair style, given to criticism rather than praise, an inclination for precision rather than passion, and a military style suitable for parade. I can not say I enjoyed the lessons, but, I did become relatively

Page 8

technically proficient at playing the clarinet. I remember one day biking to Mr. Fox’s place with some fear and lots of reservation as I knew I hadn’t done enough practice of a particular piece to satisfy him. With dragging steps I forced my way to the front door, raised my hand to ring the bell, and froze. I couldn’t do it. So I quietly snuck back out to my bike and spent half an hour resting in the park. When I finally went home I told Mum that Mr. Fox was sick but she telephoned him and caught me out. Mr. Fox and mum rescheduled my lesson. I was certainly learning about persistence. One only becomes good at an activity if you give it hours and maybe weeks and probably years of guided effort. This lesson was one of my strengths through my career as there were many times it would have been easier to give up. I later turned the lesson into a life strategy, “When the going gets tough, there are two potential outcomes. The situation can beat you, or you can beat the situation….. and the decision as to which it will be is in your head.”

I played in the Hawera High School Band, and I would offer the opinion that playing the clarinet does not lend itself to marching at the same time with the music clamped on a bracket eight inches from your face with trombones and euphoniums and base drum behind while simultaneously performing parade ground manoeuvres, left, right, double back, halt and so on ows your father.

I was entered and played in the Hawera Competitions for several years. It says something for Hawera that the annual competition in the Opera House attracted hundreds of children and some a bit older in all types of musical and dancing and speech and drama items. The woodwind section frequently drew up to a dozen competitors. I gained the second prize several years and in 1947 won the top spot with a gold medal. By aged fifteen, l was placed in the Hawera Orchestra and by age eighteen was principal clarinettist. There were four clarinettists in the Hawera Orchestra and all the others were older than me.

Ruth Dyson on flute and I played a duet over Radio Wanganui, ‘Moonlight Sonata.’ I played in numerous concerts put on by a variety of community organizations. One of the most interesting pieces that I played was a Mozart Divertimento for a trio of two clarinets and bassoon. A professional sound technician recorded the first part as I played it into his reel to reel recorder. Then when he played that back I played in the second part whilst the two parts were recorded on another recorder. Finally that duet was played back while I played in the bassoon part on an alto E flat clarinet which was picked up on the other recorder. It was the

Page 9

first time that I had heard the whole piece played. This was then placed on a vinyl record at 33 rpm which is now pretty well unplayable. However, the journey was fun.

A casual enquiry was made with the National Symphony Orchestra about the age of recruitment but they suggested enquiring again later. When I left Hawera to take a position in New Plymouth, my clarinet days finished there. I learnt many life lessons through my clarinet playing days. I have rarely felt such a sense of wonder when, fifty members of an orchestra with a variety of string, brass, woodwind and percussion instruments, sitting there each studying strange marks on pieces of paper, then …… the conductor raises his baton, and when he brings it down a variety of sweet noises harmonise to make music, and that particular sound had never been heard on this planet before. It started in one persons head, possible years ago and countless miles away, and we, the Hawera Orchestra, had recreated that vision in our town and place. That is a special type of magic to nurture ones soul.

Amateur dramatics

The Hawera Repertory Society was very highly regarded at a national level and was often well placed in national events. I acted in a few Repertory Society plays, but my main source of drama was the Wesley Players. My mother set up the Wesley Players as a club of the Hawera Methodist Church and she was the Director for most of their plays in the early years. Every Easter and Christmas we presented a play and as often as not, my sister Laureen and I had leading parts, These productions had Christian themes, but other plays through the year were solely for entertainment. A couple of musical hall types were ‘A Fruity Melodrama’, and ‘The ‘Ole in the Road.’ One of my worst moments was on stage in the Opera House to a live audience. The play was about Saint Michael and the theme was built around Saint Michael appearing on the stage with a ragged coat. Playing the part of Saint Michael, haggard and drawn, l shambled on to mid stage upon which one of the other leads would say, “Why are you wearing that terrible cloak?” And shock, horror, I had forgotten to put on the cloak. I was struck dumb. This was definitely the right time for a massive hole to appear and swallow me up whole. Fortunately, the lead improvised on the spot and said, “Why are you wearing such terrible ……… pants?” I felt lucky that I at least had pants on. Most weeks, for about ten years from aged fourteen, I was rehearsing for a play, presenting a play, or just getting over a play. I think that

Page 10

sense of drama, of presence, of stage craft was a useful life tool for many future situations.

Hockey was a fairly minor event in my life. It did however, lead to one of life’s significant events. I played in the Hawera team second eleven and we entered a team in a five-a-side tournament to be played in Eltham. My father lent me the firm’s car, a 1948 Mercury which had loads of power and, new to my experience, power steering. Our team of five, plus an older man who was to referee games, set off from Hawera. About half way to Eltham along one of the straights, I decided to overtake a car. The road was a bit frosty, the road had a highish crown, I got my right wheels a bit in the gravel just off the tar seal, and when having passed the other car pulled the wheel to come back onto the left side of the road, the Mercury went into a side slide. I pulled the wheel fast the other way and went into a left side slide. Pulled franticly on the wheel to go into another right side slide in the meantime observing that the car I had been passing was still travelling along beside me. I gave the steering wheel one more wrench to the right and decided to let the car straighten itself out. Which it did at 60mph straight for a boxthorn hedge fronted by a power pole made out of two railway lines bolted together. The Mercury snapped off the power pole and l looked up to see this pole coming straight down like a knife approaching butter. As the car fell onto its side and rammed into the boxthorn hedge. It came to rest on the left side with the power pole hard up beside it with a piece of boxthorn the size of a man’s arm half way through the windscreen twelve inches from my face. We were all stunned. Someone said, “Turn off the ignition,” which I did, we wound down the windows and scrambled out back to the road. The rest of the team went on to the hockey tournament, which they didn’t win, the referee went to hospital in a state of shock, and I hitched back to Hawera to report it to police. Frank Floss was the traffic cop and took me in his car with siren screaming back out to the crash site to supervise the recovery and to examine the scene. The second most terrifying thing that day was travelling in the police car against the flow of race traffic weaving in and out of near head on disasters. To his eternal credit, even though the car was written off, all that my father wanted to know was anybody hurt. When we did get another car, I took it down to Opunake Beach and practised putting it into and out of side slips so that I had more control for my future driving. In the 54 years since that time, I haven’t had another accident.

Page 11

Adventures in Scouting

My experience in the Boy Scouts movement was nothing short of monumental. Whatever is the age that a small boy can start in Cubs that is the age I started; probably six. Hawera had a Scout Hall down by the town swimming pool. I think several Scout groups used the hall at different times of the week. The hall had a high ceiling with a large rope strung from the centre. It was great fun to get a big swing up almost touching the walls at both ends. At one end a fixed ladder led up to the loft where a variety of tents and camping equipment was stored, mostly battered billies for cooking over an open fire. At the other end of the hall was a flag lanyard for flying the troop flag or the national flag, and two rooms, one kitchen and one toilet, all fairly basic. In the Cubs, I did what all small boy Cubs do. I dibdibdibbed, and dobdobdobbed with Akaela. We might well have tuwittowu’ed with Baloo. We crouched with our fingers on the ground and howled like wolves. We learnt a few knots, how to salute with two fingers, and how to chase one another round and round in circles. Before long, with this experience, I became a Sixer, which means Charge Hand/Group Leader of a group of similar small boys. The absolute magic of the Boy Scout movement from age six and upward is the use of small groups, Sixes in Cubs, and Patrols in Scouts. This is the stuff where one learns leadership, that is, coaching a group to achieve goals. It’s a communication and motivation strategy that is best learnt on the job.

From 1946 (aged 14), I kept a Scout Log, a written account of all my Scout activities. I was a Patrol Leader with about six Patrol members, most of them more than handy at being somewhat physical when push came to shove. Clari, Phil, Bolshie, and Noel could have been a handful but, fortunately we pulled together very well. When there were Patrol or inter-troop competitions, we always acquitted ourselves with distinction. We had a Patrol camp at Corrigans farm beside a creek with willow trees both sides. One photo shows three boys on a bridge we made with X frames at either end, a three-rope walk over the creek tied down on both sides with guy ropes. The log reports, ‘We erected this bridge with a bit of a struggle getting her up, however she came down easily enough. I had just finished taking this photo when bridge, Dave and Edgy fell into the river up to his neck. Edgy was hanging by his feet out of the water but his head was under. For a while we didn’t know what to do….’

Page 12

The record then drifts off to discuss the engineering faults we had made with insufficient guy lines. However, to the best of my knowledge Edgy didn’t die, so apparently we solved that one too. At the same camp, another photograph shows a thirty foot flag pole which we erected. We seemed to be always cutting down trees. The Conservationist badge came later on. I see also that this was the first occasion I had taken photos. A few pages further on in the log, the report is made that we developed and printed our own photographs. Black and white and Baby Brownie camera. The Riverdale camp in the same year reported ‘this was the same as every other camp except that Noel broke his arm.’ Nice to know that a broken arm was not the usual.

At the Patrol Camp in 1947, it rained all the time but we didn’t care. We built a little raft of green wood on which to place our cooking fire as it was 6 inches deep of water all over. Our sleeping tent was a bit drier as we had pitched it on the only piece of higher ground. During the night, our Troop Leader visited as it had been raining solidly for twelve hours to find us fast asleep surrounded by water beginning to lap our sleeping bags. We were really peeved off that he made us strike camp in the middle of the night. Such is life with worrying adults skulking about. The next few pages of the log mentions Patrol and Troop camps at the Stratford Maintain house on Mount Taranaki/Egmont, next to the Tawhiti stream (which it turns out is the overflow of the Nolantown sewer), and Ararata.

Then the log reports on….. the 800 mile bicycle trip with Ivan and Dave. Over a two week period we travelled from Hawera to Wanganui, up the river to Pipiriki, across to Waiouru, up to Taupo, then Rotorua, pause for a week for a Scout gathering to meet Lord Rowellan, World Chief Scout, then across to Hamilton, then down to Waitomo caves, continuing to Mokau, Lepperton and home to Hawera. I have to say we caught rides when it suited us. An old Maori guy in a battered truck gave us a ride from Patea to Wanganui. We had expected to take a river boat from Wanganui to Pipiriki, only to be told that it no longer did the trip, so we took the bus to Pipiriki. It was a winding, grinding unsealed road which took four hours to complete. We camped at Pipiriki and the next day, pushed our bikes 17 miles up one long hill to Raetihi, also unsealed. Not great for bicycle passage but great for the development of character and tired leg muscles. The next day past Ohakune, we arrived at Rangataua and it started to rain so we asked a farmer if we could stay in his barn for the night. He gave us a room in the house where his wife gave us a slapup meal.

Page 13

Fortunately, it rained the next day so we stayed on and had three more great meals. I wonder how often that sort of hospitality is offered to strangers these days. The next day we did eleven miles up hill by train. See, we were getting smarter by the day. Then a long bike day along the Desert Road to Lake Taupo where we stayed at a bach for the night. The next day we pushed on to Wairakei where we pitched camp and had swims in a hot pool. At Rotorua we pitched camp at Dickens Motor Camp at Ngongotoha [Ngongotaha]. We had fun in the Blue baths, were intrigued with the Brylcreme dispenser, met a beaut damsel (hubba hubba is recorded), and met Lord Rowellan in a milk bar where it is recorded ‘we shook hands and shared jokes.’ I have no idea what sort of jokes one shares with the World Chief Scout, but there you are, we did it. After the Rotorua visit, we pushed to Hamilton for the night then down to Waitomo Caves where we spent the night in a hostel. The next day, it is recorded, we got our first puncture. The next day we biked to Mokau that is, 75 miles (about 125 kilometers) of hilly country, head wind, driving rain. A lot of character being developed if somewhat wet. We bunked down that night in a bus shelter with a gravel floor and to this day I can describe the experience. The walls didn’t go all the way down to the floor creating ideal conditions for a strong, cold draught. The gravel produced hard, lumpy, cold, unwelcoming feelings. Cooking the dinner on the billy proved unreasonable so the food was mostly raw. The next day continued 70 miles to Lepperton with once again a head wind and driving rain. We felt by this time that we had had our fair share of character development and caught the train the last 50 miles home to Hawera. Three newspapers carried the story, “Four Hawera Boy Scouts Undertake Long Cycle Trip.”

The log then reports on a First Class signaling camp at Hicks’s in the Tongahoe valley, a First Class badge hike, Easter 1949 Troop camp, a tramp on Mount Taranaki over ten miles of alpine track and river bed course, and a one week tramp and holiday in a back country bushman’s hut in Ararata. All in 1949. This was one of my School Certificate years. The log carries on with a range of Scouting and back country tramps and camps through the following years.

1954 announces the first of my Wanganui cruises, a flotilla of canoes of all types on a National Scout expedition. Alan and I had been preparing for twelve months, raising the money, building a canoe, having waterproof fitted bags made so that if we tipped over, all of our gear would remain safe and dry. A party of twenty young men (by this time, I was 22 years old) gathered at Cherry Grove, Taumaranui [Taumarunui],

Page 14

preparing to travel 144 miles by canoe, through 239 rapids over eleven days to reach the river city of Wanganui. Phil and I had taken the slow train to Taumaranui where the tour group leader, Jim, met us and took us to the first camp site. Amongst the craft assembled were a 26 foot Maori Dugout, a three man Canadian Rob Roy, and another canoe which was immediately called ‘the Ripper’ on account of it suffering at least three rips a day to its canvas. Of the 239 rapids, we learnt 239 times that a 26 foot Maori Dugout will not ride over the waves, which as a rule are about ten foot apart, but will ride through each wave and will fill with water from the front to the back. Quite commonly the guys in the front will celebrate getting through a rapid, while the paddlers in the back were up to their necks in water. The Canadian Rob Roy, however, was so tippy that of the 239 rapids, it tipped over about 139 times. Phil and l, in HMS Seagull, tipped over once, and that on day five, on rapid 194, the back breaker Autapu. At the end of each days paddling, we would look for a good camp site on the river banks, pull in and make camp. We carried small two man pup tents and cooked everything over open fires.

We operated in three patrols, each with an experienced Patrol Leader, Jim was the Expedition/Troop Leader, and Mike was the Quartermaster in charge of a mountain of stores. We had to carry all of our food for twenty hungry young men for eleven days, plus all of our water. The Taumaranui sewer runoff ran into the Wanganui River so if one accidentally swallowed a teaspoon of water while swimming, there was a good chance of getting bangbang. One of the ten newspapers articles about the trip, reports that the Scout Party painted a flag pole near the confluence of the Ohura and Wanganui Rivers that was erected by Maori at the end of the Hau Hau wars. My log reports, “One bright spot was the case of the Hau Hau totem pole, erected at the beginning of the Maori wars. It is situated at the side of the Ohura River so we undertook to scrape off the moss and paint it with Maori paint – fish oil and red ochre. It was a terrific job and nobody could stand it up the pole for very long. We used leg irons and a rope around our girth. Ian did his spell of ten minutes and at the peak of suffering, shouted down that although Hillary had got knighted for climbing Everest, he hadn’t had to paint the flippin’ thing.” The reporters on hand soon picked that up.

The day before we arrived at Pipiriki, we explored a previously unknown cave. Our Leader Jim, had a copy of an old diary of a Rev. Richard Taylor published in 1921 which described a cave, but whilst we couldn’t find that cave, we found a hole

Page 15

in the ground with a steam of water disappearing down it. We climbed fifty feet by rope down the waterfall into a cave fifty yards long and ten foot wide. At the bottom, there was virtually no light and within a few steps, apart from our torches, the only light was glow worms high up on the ceiling. We followed the water to a large pool, dropped down and followed the next waterfall to the Puraroto cave on the bank of the Wanganui River. Whew. After fifty more miles of slogging the last stretch of the river, twenty miles of which is tidal, we were met at Wanganui by the New Zealand Chief Scout, Major-General Lockhart, the Dominion President Mr. Christie and the Taranaki and Wanganui District Commissioners.

The log reports that the following year, l decided to do the Wanganui River again, taking Johny and Stanley along for the trip. As we were about to head off out of Cherry Grove, a chap wandered up and asked if his group could join us as he had promised them a trip down the river and didn’t have a clue or map to know how to go. So our party of Johnny, Stanley, Neville, Trevor, Elaine and Brian Sumbodyorother set off down the river. After two days we sighted another canoe on the bank and they pleaded with us could they join us. So we added Jack and Helaine to the crew. The log reports that at Retaruke over night the local dogs through the night stole our supplies of meat, bacon and bread. We compensated by catching eels every night, chopping up steaks and putting them on the embers then eating them for breakfast. The following year, 1956, I did the trip again with Phil, Les, Mike and Darryl. On this trip the river was in flood about ten foot, it rained the whole time, we caught and cooked and ate a goat. We finished the journey at Pipiriki three days earlier than expected because of the roaring torrents.

The following Easter, l had my final river/canoe trip, this one down the Patea river. Trevor, Phil, Les and l pushed off from Mangamingi, at the back of Stratford. Unlike the Wanganui river which had been previously traveled by steamer and hundreds of canoes, the Patea river was untamed. Our maps showed that from Mangamingi to Patea was only half the distance of the Wanganui but about the same fall of 120 feet. There was very little water at Mangamingi and we had to get out of our canoes at the first few rapids and push them through the shallow rapids. Fortunately all of our canoes were made of plywood. Around the first corner we came upon a wild goose so we gave chase, caught it and stowed it on board for dinner that night. Around the next corner, we came across a gaggle of geese in a fenced paddock, obviously part of a farmers stock. Sorry, head down and paddle like mad.

Page 16

The going that day was tough. Log jambs, shallow rapids, hordes of large mosquitoes, sand flies and every other type of flesh eating insect known to man. We made very little progress the first three days and we were starting to panic as the days of Easter were running out. On the fourth day, according to our maps, we were about half way to Patea. We figured out that we were within five miles of the Tongahoe Valley up very steep hills. Above the bush which lined the river, we could see farm tracks. We decided to hide our canoes up in the bush and hike out to civilization and call home for the rescue parents. Fortunately, all of this worked out as planned. About three weekends later was ANZAC weekend, giving us another three days to complete the journey. Which we did arriving at Patea river mouth about midday on the Monday.

This concluded my adventure through the Scouting movement. By this stage I was Assistant Troop Leader but had no wish to carry on to higher office. The lessons I learnt were immeasurable. The major lessons were about leadership and project planning and execution. If I tried to extract all of the things I learnt through my Scouting adventures, it would take a step into the world of theory which is not what this is all about. If I was to quote a subject of one of my research projects, it would be, “I don’t know what l learnt but I use it all the time.”

The keen gymnast

My other great love during my adolescent years and into young manhood was gymnastics. I think it started at Hawera High School with our Physical Education teacher Murial Hughes giving a group of us plenty of encouragement. Murial was the only teacher I remember giving me unqualified encouragement. Every other teacher would give the occasional encouraging word followed immediately with “could do better”

A small group would often stay after school and practise tumbling in the school hall. This before we had a purpose-built gymnasium. I remember taking a flying dive over a row of five chairs onto a roll on the tumbling mats. We would also practise forward somersaults and handsprings on the tumbling mats. We had a horse for vaulting over but I don’t recall any other apparatus.

Page 17

I joined the St. Johns Gym Club around 1948 and attended Thursday night gymnastic sessions in the St. Johns Presbyterian hall. The hall was not very large so to get sufficient run to vault the horse, we started the run in the entrance passage. The Gym Club had a horizontal bar made of wood about 6cm thick. This meant you couldn’t get your thumb and fingers spread around it. We also had parallel bars that were as stiff as iron, and swinging Roman Rings. We held camps which included a bit of tumbling and exercise sessions but were mostly loafing about and swimming. About this time, the Danish gym team toured New Zealand and we had a hand in promoting their exhibitions.

In 1951 a party of nine travelled to Wellington to observe the New Zealand Gymnastic Championships held in the YMCA. This was my first experience with a YMCA. The Gym Champs were a big thrill to us all as they were of a standard we hadn’t seen before. At the tail end, when the competition had concluded, a man wandered into the gym, changed down to shorts and singlet, and tried out some of the apparatus. His standard was another higher level again and we wondered who he was. it transpired that he was a Hungarian refugee named Andras Pillich, he had very little English language but was immediately viewed by the Hamilton YMCA as a potential recruit as coach.

Our popularity with the local Hawera public grew year by year as we put on displays of tumbling, speed teams vaulting the horse, novelties such as diving through the flaming hoop and various balancing acts. We had a “Balance Squad” comprising six members who entered walking in a handstand and then did group balance cameos. We put on ten displays in 1953 including two for a Queen Carnival, The A & P Show, the Hawera Progressive Association, the Tawhiti School, The Wesley Sunday School, New Plymouth Girls High School, and the New Plymouth YMCA.

Many of our club members started to make regular visits to Hamilton, partly to receive some coaching from Andras Pillich who was now employed as the gymnastic coach at the Hamilton YMCA, and partly to talk about setting up provincial gymnastic associations from which to build a national organisation. In 1955 the Auckland, Waikato and Taranaki Gymnastic Associations were established. I was elected on to the Executive Committee of the Taranaki Association. The first National Championships were planned for October 1955 to be held in Hamilton. A small group from our club, Trevor, Mike, Darryl, Bill and l started making monthly weekend visits

Page 18

to Hamilton, preparing ourselves as contestants in the coming event. Sometimes we travelled by car, sometimes by train. The train left Hawera at around 10pm on the Friday night, and arrived in Hamilton at 4am. Most times, Colin would meet us and we would bunk down on the floor at his place. On one of these occasions, Colin had telephoned the night before to say he was not available and we were on our own. We had thought there would be some type of hotel open at Frankton Junction. When we arrived, there was a taxi at the stand who informed us he didn’t know of any accommodation available at that hour of the night. I asked him to take us to the Police Station. The Duty Sergeant firmly told me that the Police Station was not a flop house and we should ‘move along please sonny. Not to be deterred l pointed out that we had nowhere to move along to and the gym didn’t open until 9am. We needed a bed. I suggested that if we went outside and threw a stone through the window he would be obliged to put us in the cells for the night. He reluctantly agreed to let us spend the rest of the night in the women’s cell on the understanding that we had to be evicted if they had real criminals to hold, and that we had to be out before the next shift took over at 8am. We signed for a thin blanket and were locked in the cell. The graffiti in the women’s cell was so graphic and absorbing, I don’t think we got much sleep, but the education gained was immeasurable. Our gymnastics wasn’t up to scratch that weekend.

About this time, I started experimenting with a couple of horizontal bar tricks that I had seen Tony Curtis do in a movie. The first was then called ‘the Grand Circle’, which amounted to throwing yourself into a handstand on the high bar and going around and around in that position. I was not too sure of the risk involved as I had heard that at the bottom of the swing the pressure on your hands was three times gravitational pull. So I had made arm straps with leather which were then looped around the bar in case of an unexpected exit. It worked fine most times with a lot of grunting, shoving and general muscle action. I learnt later, of course, that using muscles was entirely the wrong way to go about it. The other trick was ‘the Flyaway’. This amounted to throwing almost to a handstand on the high bar, swinging through the bottom and when starting to go up the other side, let go the hands and you would, with a bit of luck fly through the air revolving backwards sufficient to land on your feet. Bravo. I made mistakes in the timing of letting go every now and again. Once I let go too late and somersaulted upward to crack my shins on the bar whilst upside down and eight feet off the ground to land in a heap under the bar on my

Page 19

neck. Nasty. Another time in a display in St. Johns Hall I let go a trifle early and shot like a rocket straight for the stage landing with my hands against the stage. Just saved my head by a whisker.

And now, in October 1955, we were about to find out if we were ready for the first New Zealand National Gymnastic Championship. A Youth Team and a Mens Team travelled to Hamilton where the competition was held in the YMCA. We had been practicing compulsory routines on the floor exercise, the parallel bars, the horizontal bar, the rings and the vaulting horse. There were teams competing from Hamilton YMCA, Hamilton Tech, Hawera St. Johns, Auckland, Gisborne and Wellington. All the compulsory routines went well enough. Then each competitor had to perform a routine of ones choice on each piece of apparatus. The Taranaki Herald newspaper reported, ‘HAWERA GYMNASTS RUNNERS-UP TO NATIONAL CHAMPIONS AT HAMILTON. Runners-up to the New Zealand champions, St. Johns Young Mens Gym Club, Hawera, scored well when it sent two teams – D. Oliver, W. Drake and T. Humphrey (senior) and M. Bourke, D. Skiffington, and B. Hedley (junior) to Hamilton to compete in the first New Zealand gymnastic championships. The senior team was second in the overall championship to the winners, Hamilton YMCA, only recently returned from a tour of Australia, and in the individual competition Dennis Oliver won third place followed closely by Trevor Humphrey and Bill Drake in that order.’

I think that accomplishment was the highlight of my gymnastic activities although, I did go on to gain third place in the Mens A Grade Competition the next year, was the New Zealand Chief Judge for Mens Gymnastics for two or three years in the mid 1960s and was the President of the New Zealand Gymnastic Association for one year in the late 1960s. Neither position was comfortable with lots of dissention to cope with. I was also President of the Taranaki Gymnastic Association for about five years from about 1957 on. Somewhere in there, prior to 1956, I set up a Wesley Gym Club and we had about twenty boys who met once a week to try out their stuff. I remember standing at the vaulting horse ready to catch the next kid who was asked to call out what vault he was doing. Billy started running and called out, “I’m doing a fox trot.” Fortunately, just before he sprung into the air, I figured out he meant a ‘Wolf Drop’ and was able to provide the appropriate support. We put on annual displays of the boys gymnastic tricks, much to the delight of crowds of parents.

Page 20

A busy social life

All of these activities didn’t leave me much time for what you might call a private life. From around the ages of 16 to 23, the weekly plan of community activities was ; Tuesday night – orchestra practice; Wednesday night – Wesley Gym Club; Thursday night – St. Johns Gym Club; Friday night – work in the grocer shop; Saturday nights -Scouts; Sunday nights – courting; Monday night – resting, drawing strength for the next round. Which brings to mind Mark Twains expression, “Schooling interrupted my education.”

I should perhaps make some mention of my courting activities. I tended to stay with one girlfriend at a time for a year or more until something interrupted our relationship. Take Mary from Manaia for example. I biked to her place pretty well every week for more than a year, but when for about the fiftieth time her father asked if I was ‘saved’, to which I was never quite sure what to answer, I decided to look elsewhere for company. Then I was with Pam from Opunake for a couple of years. Fortunately, by this time I had grown out of the bicycle and was borrowing my father’s car for the 42 kilometre journey. Somewhere in there was Shirley from Stratford.

And then, Johnny and l were sharing a girl who was here on a visit from Australia, Johnny one week and me the next, when her birthday came up on Johnny’s week. “I’ll fix you up with a date,” said Johnny, “and you can bring her to the party.” He said he would pop along to Maypole number 3 on the following Monday morning at 10am as he knew that she walked from the Bank of New South Wales to the cake shop to get the bank staff’s morning tea. This arrangement sounded satisfactory so,… there she was, and,… there I was, and,.. I was smitten. What a warm, sunny smile. What an attractive young woman. I was hooked. I courted Jean from 1953 until we married in June 1956. Jean flatted in town with a girl friend, worked at the Bank of New South Wales and, in the weekends went home to the family farm at the back of Mokoia, about eight miles from Hawera. I travelled many a time out to the farm during weekends and sometimes helped Jean’s father with a bit of farm work.

Don Reisterer was back in Hawera for the farewell of our Methodist Church Minister, Rev. Gordon Hannah. At that time, Don was employed by the National Council of YMCAs of New Zealand as Assistant National Secretary. He overheard

Page 21

somebody congratulate me on the 1955 National Gymnastic Championship results and my particular success. He congratulated me and suggested I might be interested in the position of General Secretary of the New Plymouth YMCA which was vacant and which had been vacant for some time. From what I could make out, it involved mostly coaching boys in gymnastics, and conducting summer camps. This was a major crossroads in my life. It would mean a departure from the security and probable promotion in my father’s Maypole Stores, and entering an occupation of my two favorite pursuits, gymnastics and camping. There was a period of consultation with the National YMCA Secretary, George Briggs, a matter of prayer and a lot of heavy thinking. In the long run, I decided in March 1956 to apply for the job. I saw it, in a sense, as a type of Christian mission, as it was part of the effort to keep boys and young men in healthy pursuits, developing character and their leadership potential.

Page 22

Chapter two Enter the New Plymouth YMCA

I drove to New Plymouth and attended the interview held in a poky little room half way between the basement and the public hall of the YWCA in Powderham Street. I think there were six men that interviewed me as I gave my responses to some fairly stupid questions, such as, “How do you make Cocoa for sixty boys at camp?” Other questions were more to the mark such as my skills at coaching, at leading groups and my Christian convictions. They asked me after the interview to wait outside. As I departed and even before the door was closed, I heard Frank ask in a loud voice, “I don’t know what we have to talk about. He is the only one that has applied ” After a couple of minutes, I was asked to enter the room again and was informed I had the job and to start as soon as possible. I gave the date in March that I was available and informed the committee that as l was getting married in June, I would need two weeks leave without pay at that time.

At some time during the interview, the seed was sown that there was a need for the YMCA to obtain its own building as it was at the time renting space at the YWCA. I was to learn later, that the YMCA had historically been formed in New Plymouth as the Boys Work section of the YWCA. It had in the 1940s become a legal entity in its own right, but had never detached its activities from the YWCA building. It had over the previous few years developed a camp site on property leased from the Electric Power Company at the Meeting Of The Waters called Camp Huinga. A lodge with kitchen, an ablution block, and about three small huts had been erected.

I had been told that there were about 200 boys enrolled in gym classes, but they had been in abeyance for several months so it was questionable how many would re-enroll. In the event, just a few over 100 enrolled. For the first time I had a class of five year olds, about twenty little ‘Tiny Ys.’ There were two classes aged up to about ten, a class of eleven to thirteen year old boys, and a dozen or so high school boys, the ‘Hi Y.’ The Hi Y members were also voluntary leaders with the other classes and acted as group leaders with all of the activities. These boys made a contribution probably beyond their understanding, not only to my career responsibilities, but also to the development of the small boys in their charge, and most certainly to their own leadership development. The boys all called me ‘Skip’, carrying on a tradition from previous staff at the New Plymouth YMCA.

I had an office attached to the meeting room halfway down to the basement. The basement of the YWCA was used as a gymnasium but its limited size made it

Page 23

unsuitable for a significant range of events. It was approximately twenty metres long and about eight metres wide but its main limitation was in its ceiling height which little more than three metres. That made it hopeless for the horizontal bar, roman rings, fairly tight for the parallel bars, way out of the question for basketball, volleyball or badminton. All of the boys classes were after school except for the Hi-Y which was held on Friday evenings. The boys all paid fees per school term, so for the first couple of weeks I was busy before and after classes receiving the fees, writing receipts, and making out membership cards. This certainly helped me to remember the boys names. Ten years later when I had five hundred boys in gym classes and one hundred and eighty boys at camp, I still knew all their names because of writing the receipts, often addressing an envelope, reinforcing these codes into the memory banks.

Six weeks after I started, I was cleaning out some drawers in the desk, and found some accounts that had been unpaid for three months. They amounted to a total of two hundred and forty pounds. I telephoned the Chairman, Laurie Cooper, and he instructed me to pay the accounts. So I made out the cheques and the Chairman signed them and posted them away. Two days later, the Bank Manager telephoned to say that our account was overdrawn and we should make no further withdrawals until a credit balance was regained. Horror! What about my wage for the next three months?? I relayed this information to the Chairman but he was a bit stunned and offered no suggestions of how the situation could be remedied. Enter the miracle!! The next day, Dan Archibald, Head Gym Master at New Plymouth Boys High School, knocked on my door, asking if I could help at the Boys High each morning in the gym as they had two or three classes at a time and it was too much for one teacher. Dan knew of my association with St. Johns Gym Club in Hawera. He knew I had no formal teaching qualifications but that l was experienced at taking classes in gymnastics and general fitness training. For the next seven years, every week day morning from 8:30am to around 12 noon, I was assistant gym master at New Plymouth Boys High School, and from 1:30pm until 10pm, I performed the duties of the General Secretary of the YMCA of New Plymouth. The money I earned from the Boys High was about five times more per hour what I was paid at the YMCA, but the Boys High paid me no holiday pay or sick leave.

Strange as it may seem, this era was prior to the popularity of wearing track suits in the public arena. So, I changed my clothes, either taking them off or putting

Page 24

them on, fourteen times a day. At the start of the day, I took off my pyjamas and put on my street clothes; at the Boys High I took off my street clothes and put on my gym shorts; when finished I took off my gym shorts and put on street clothes; after lunch at the Y I would take off my street clothes and put on my gym shorts; after afternoon classes l would take off my gym shorts and put on my street clothes and go home to dinner; after dinner back at the Y l would take off my street clothes and put on my gym shorts; after gym I would take off my gym shorts and put on my street clothes; finally I would go home take off my street clothes and put on my pyjamas.

Much of the time at the Boys High School, the regular teacher took the lesson, while I helped around the edges getting the slow or reluctant boys involved. There was, however, a succession of regular teachers, some lasting a year or two and others a week or two. Within a couple of years, I took the lessons as often as not. During the summer, we could set a cracking pace. Next to the gymnasium on one side was a sports field, and out the front was the school swimming pool. I would set up an exercise circuit in the gym with about ten different exercise stations. When a class arrived, I would conduct a ten minute warm up session, then the boys would run twice around the sports field, twice around the circuit in the gym, then two lengths of the school pool. Fit boys loved it. The others usually got around the course if somewhat tardily.

Later in my career, probably around 1963, I had five New Zealand Champion sportsmen, who had previously been pupils at New Plymouth Boys High, come back to me for fitness training. I would analyse their sport to figure out the particular type of fitness they needed. They were Kevin Gibbons, pole vaulter; Peter Quin, skier; Brian Purser, badminton; John Dean, cyclist; and Norman Reid, who already had an Olympic Gold Medal for walking, but wanted to get more upper body strength. The type of thing I did could be demonstrated by the action I took with the cyclist, John Dean. I watched him ride a couple of races, and viewed a few films – this was before the days of videos. I noted that in every race, he was right up there with the leading bunch, and in the mad final dash for the line, he would finish behind the others. I put him through a series of exercise tests and noted that his pulling arm muscles were much weaker than his pushing arm muscles. In analysing what is required of the body in the final dash, it is the strength of the arms that allows the rest of the body to furiously pump the pedals. So I put him on an exercise regime that over a few months gained a balance in the strength of the arms, and he started winning races.

Page 25

Kevin Gibbons I coached mostly on the rings and the ropes swinging with his hips over his shoulders; Peter Quin I had on the pommel horse getting the idea of a rotational balance between the shoulders and the hips and on the trampoline getting the idea of changing direction whilst in mid-air. It was an interesting period of my gymnastic days.

In the meantime, at the YMCA, we took in a group wanting to do Judo and started the YMCA Judo Club. With our contact with Andra Pillich, we learnt of the German address for Olympic standard gymnastic apparatus, and with the help of George Briggs, National Secretary of the YMCA, we applied for Lottery money and started to import first rate gear. What a difference! Less grunt, more swing. Some of the Hi-Y showed some promise at competition gymnastics, so we gained approval to move our good apparatus to the Boys High gymnasium and held our Friday night Hi- y sessions there. A few years later, two of our previous Hi-Y members, Bryan Jury and Mike Ranger, had achieved such a high standard to be part of a New Zealand team that competed at the World Gymnastic Championships held in Dortmund, Germany.

In June 1956, I married Jean at the Hawera Methodist church. A real knee-knocking event. I don’t know why I was so nervous but I certainly got the shakes. We travelled to Hamilton then Auckland ready for the honeymoon in Fiji. Jean’s father George, had paid for her two sisters to have a school trip to Australia, and had promised Jean an equivalent amount. Jean had earned savings of one hundred pounds, so, with Georges contribution we spent all of Jeans savings on the fortnight in Fiji. We had a week in Suva staying with the family of Gladys March, a school friend of Jeans, and a week at the original Korolevu Beach hotel. Our accommodation was in a thatched bure on the white sand beach next to the coral lagoon. This was the easy way to fall in love with Fiji.

We bought our first house in New Plymouth on Ngamutu Road for 2300 pounds. This was a very modest bungalow with two bedrooms and a very steep footpath accessing from Ngamutu Road. | used 400 pounds of my savings, my father leant[lent] us 1000 pounds and I borrowed 900 from an Insurance Company. Five years later, we sold that house for 2800, quite a good margin in those days. I also spent 400 pounds on a Prefect car, and 100 or so on furniture. We started married life using wooden apple boxes for seats in the kitchen/dining room, and every piece of furniture was as cheap as one could get.

Page 26

Back at the YMCA, as each term progressed, the numbers in the classes increased, so that by the end of the year there were 150 boys engaged in Y Gym classes.

Camping for boys

I started to prepare for my first camps at Camp Huinga. That first year, we held two camps, both for boys aged ten to thirteen and we had 24 boys at each camp. Board member Frank had obtained four workmens hut on the cheap from the Army. These were equipped with eight bunks each to accommodate the boys. These huts were so small however, that the floor space between the bunks being no more than two feet, was not sufficient for eight boys to get out of their bunks at the same time. They also had a lot of knot holes in the timber walls. I used to go around the cabins at night to discourage the boys from talking after lights out but, I became wary of this practice after a stream of urine came jetting out of one of the knot holes. He should have gone before he got into bed. Once again, the Hi-Y members were the cabin leaders and Jean was the Camp Cook. One boy, Peter said to her, “What do we call you? Are you the Cookie ?” to which Jean replied, ” I don’t like being labelled like a peanut cookie.” Peter considered this and asked, “Can we call you Peanut?” To which they agreed and from that day forth in excess of 2600 boys who attended one of our camps called Jean ‘Peanut.’

One day, a small boy came up to Jean and said, “I don’t think my mother will let me come back to camp, Peanut.” Jean asked, “Why is that Arthur?” “These boys are teaching me rudeness.” “What on earth are they doing?” asked Jean. “They are jumping out of bed and wriggling with no clothes on.” Jean said she would make sure that horrible and nasty practice was stopped. Arthur came for about ten years to Camp Huinga.

I ran the camp in a somewhat military style with morning inspections, kitchen and ablution block fatigues, lining up outside the cabins and marching into the dining room for meals. We had morning devotions in an outdoor chapel that we built in amongst a group of native trees and a morning sports competition. Over the years we designed and built an obstacle course we called “the commando course. ‘ In the middle of it, after a rope swing over a ditch was an underground tunnel that was a bit of a maze with a few blind alleys. Once you crawled past the first bend, it was absolutely and completely pitch black. We had constructed it by digging trenches,

Page 27

then covering them with planks of wood then covering with dirt. Every year, at least one kid would go into total panic at the complete darkness and stand up erupting the covering dirt and planks.

One of the entertaining traditions we developed was that each cabin group sang their own grace as soon as they had their meal and were all present. The words were, “For health and strength a daily food we give the thanks O Lord, For fellowship and all things good we praise thy name O Lord.” Each cabin would try to put it to a different tune. So we heard Hinando’s Hideaway, Rock Island Line, Mary Had a Little Lamb, and many other tunes being distorted to fit the Health and Strength model.

We began lining the walls of the dining room/lodge with 4inch wooden match lining, and pokerworking each boys name and home town onto the wood. Over the years, most of the walls were lined in this way, a living, evolving history of all the boys that attended Camp Huinga. Boys came to Camp Huinga from different areas of Taranaki, many from farming families who were looking for a way to give their boys a break from the farm over the summer school holidays.

My second year as Camp Director at Camp Huinga was a very testing time. A real outright horror. I was hit, as some would say, with a triple whammy. Jean gave birth to our first child Robert, on December 13th 1957. As she was unavailable to cook for camp, I hired a Dutch/Kiwi lady as Camp Cook. On the first night, she became so overly excited at the kids and camp she went into a nervous breakdown. At four o clock in the morning I had to call the doctor who stuck a large needle into her which knocked her out and he carted her off for the duration. I would have to do the cooking and Directing. Whammy One. Jim, my Programme Director, a senior high school student leader, the next night went down with influenza and a temperature of 104 degrees. His parents had gone north on vacation so I had to nurse him, direct the camp and cook. Enter Whammy Three. It rained for ten days without a minutes stop. Forty boys and their cabin leaders for ten days without a skerrick of support. The kids and the leaders were wonderful. Entertained themselves, invented indoor competitions, quizzes, games and ran the whole show while I cooked and nursed Jim through the term of the camp.

The numbers attending Camp Huinga increased by almost fifty percent each of the first few years until we were conducting three camps each of ten days for sixty boys at a time. The Cabin Leaders started to be drawn from those boys who had attended as campers for several years. The need for the Leaders to have a camp for

Page 28

themselves without younger charges to absorb their interests became obvious. I approached the New Plymouth Lions Club for funds, searched and found a site within the Egmont National Park where the Waiweranui Stream flowed from the Parks boundary into farmland above Okato. It took a couple of years work, but the funds were found and the lodge constructed with about sixteen bunks. Most of the Leaders would do a ten day duty at Camp Huinga and then attend a two week camp at Waiweranui. Things were fairly basic there. Much of the cooking over an open fire; a pit-dug toilet in the bush; down to the river for water for cooking and downstream for washing. The morning body wash tended to be somewhat spartan with the water not too far from the snow and ice. The hikes were tough, all uphill on the way out but fortunately downhill on the way home. A hike to Bells Falls took three to four hours and a climb of about three thousand feet.

I employed a Camp Director to oversee Camp Huinga and Directed Camp Waiweranui myself with an experienced mountaineer as Assistant. The difference in rigour between the ‘kids stuff’ of Camp Huinga and the rugged survival mode of Camp Waiweranui became obvious before long.

Then, the Egmont National Park Board advertised the availability of the North Egmont Chalet to any community group willing to keep open the public tearooms. I put the proposition to the Board of Directors that we take a lease on the property, conduct junior adventure camps for 13 and 14 year old boys, twenty four at a time, plus group leaders, which we did. We advertised in the local newspapers for anyone, probably retired, willing to operate the tearooms at their own risk and reward, to live accommodation rent free at the Chalet, paying only for their use of electricity. A very interesting assortment of chalet tearoom managers operated the chalet for the next several years.

Jean and I, and by this time three children, Robert, Richard and Shelley, together with Samantha the dog, Viti the cat, and a whole bunch of household and personal things, would load up the station wagon the day after Christmas, and make the chalet our home until the end of January.

We operated two camps a year, a fortnight each. I would keep in touch with Camp Huinga by telephone and Camp Waiweranui by CB radio through a relay station, and once a week got in the car and visited each camp whilst the Camp Challenge programme at North Egmont was run by my Deputy Camp Director. By this stage we had over three hundred boys through our camps every January. We

Page 29

conducted Leadership Training camps once or twice a year for the cabin and group leaders.

After my trip to USA in 1969, we also conducted day camps from the stadium in New Plymouth for boys and girls six to eight years of age taking the total of campers each summer holidays to over 480 happy campers. I loved visiting the day camps on their last night when forty little kids with their group leaders and their Camp Director in their hired bus would set up camp on the banks of a stream down on a beach, make sleeping tents out of plastic sheets, cook their sausages and potatoes over an open fire and spend the night camping out under the stars. What an adventure.

This arrangement of four camp locations gave a wonderful progression of development of each individual child. Later, we developed the skills to help each individual camper set personal growth goals for their target in camp. I believe the character dimension in camping is a potential development experience difficult to match.

Camp Challenge at the North Egmont Chalet opened up the possibility of significant outdoor experiences. Each camp had an overnight camp out in the original rain forest following some off-track expeditions. Some of these followed natural terrain and some used map and compass methods. Then each camp of 24 boys and their leaders would complete a one day climb to the summit of the mountain. This was a tough exercise and required strong climbers in muscle and wind and good mountain leadership. The critically important leadership skill was being prepared to turn back when the environment presented too many potential risks. Over several seasons I climbed to the summit thirteen times and took my sons Robert and Richard when they were around eight and ten years of age. Our dog Samantha followed one of the leaders who was on a private climb to the summit. Samantha had to be put into the haversack to be brought down and the next day her legs were stiff rigid. She had to be helped to lie down as her legs poked out as she lay on her side.

One of the interesting side benefits of this move to use Mount Egmont with two camp locations was our increase in a cadre of useful group leaders with mountaineering skills. Some joined as members the North Egmont Alpine Club but found that many of their expeditions were a bit more expensive and extensive than our school boys could afford. So we formed our own YMCA Tramping Club. Those leaders who had left school took the positions of club officers and they planned a

Page 30

year of activities around all areas of Egmont. Our club was coached by Dave Rawson, a very experienced mountaineer and local coordinator of Search and Rescue. Not long after our club was formed, a party of girls from New Plymouth Girls High School became overdue and were notified as lost on Egmont. Dave swung into gear around midnight and sent several experienced search and rescue teams into various possible routes the girls might have taken. Dave considered our boys the most skilled at off-track maneuvering so sent our team down some ridges in case the girls had wandered off the track. All groups carried CB radios, first aid kits, water and hypothermia rescue kits. At about three in the morning the signal went out, the YMCA boys have found the missing girls party and are bringing them out. What a proud bunch of YMCA Tramping Club members we had. The newspaper headlines made great reading to a lot of mothers, proud of their boys. There had been more people killed, at that stage, than any other mountain in the southern hemisphere through foolhardiness and misadventure.

Highlights of the growing gym classes

Meanwhile, back in New Plymouth, our gym classes for boys were increasing in numbers year by year. When our numbers reached 250 we moved out of the YWCA and relocated to the A & P Society hall, next to the Army Hall. There we had bigger space and a much dirtier floor. | used to clean the floor with kerosene and sawdust, and every day of every week hundreds of small boys would come to YMCA in nice white shorts and leave in grubby brown gym gear. They certainly had very diligent mothers. And still they came. The numbers grew to 500 and I employed an Assistant who helped out with the classes.

In the early days, the Hi-Y practised a range of activities preparing themselves for the Older Boys National Tournament. Each August school holidays I took a team of six boys to Wellington, Christchurch and other YMCA centres where they would compete and meet with boys from eight or nine other YMCAs. The tournament included inter team contests in gymnastics, volley ball, basketball, table tennis, relays, impromptu speeches, prepared speeches, and scripture reading. The boy who won the scripture reading would give the reading at the church service on the final Sunday. All the boys were billeted out by host families for the duration of the

Page 31

tournament. It was a grand way of building the national identity of the YMCA from the ground up.

Locally, the YMCA held Father and Son Banquets in the A & P hall for 400 boys and dads. Magnus Hughson, our YMCA President described the peas pie and puds meal as ‘a sumptuous feast’, much to the delight of the Ladies Auxiliary. Mind you it was followed by jelly and ice cream.