- Home

- Collections

- MILLER OA

- My Experiences in World War Two

My Experiences in World War Two

Page 1

August 2012

Entry and exit from POW camp

Listening to Mark Sainsbury, TV presenter, comment about his late father’s war experiences during World War II, I felt as if he was describing my own army experiences. It appeared as if his father and I were on parallel courses.

That is: First Echelon, Egypt, Greece, Crete, POW at Stalag V111B and long service.

I am not sure if our paths crossed directly. However I have since learnt from Mark that his father was in the Artillery. Mark regretted not asking his father more about the war.

Thus I have recounted some of my own experiences.

I was in the uniform of the Otago Mounted Rifles, on my way to camp, when war was declared in October 1939. After returning to the farm that I was working on near Dipton, Southland, I enlisted, and was sent to Trentham, Wellington, where we were given a 303 rifle, the latest in technology (well it was in 1914/18). We were given a number, mine being 5851 and commenced three months of basic training. At the end of this time we were positioned in our respective companies. I found myself in Division Provost Company even though I had requested a posting to the Artillery but the only big guns were the ones with red on their caps!

On the 4th January 1940, 4 days after my 22nd birthday, we sailed from Wellington on the SS. Strathaird (nobody was allowed on the wharf to wave goodbye) and the last we saw of New Zealand was Mt. Egmont, sitting in the sea. Our convoy was aimed for Fremantle where we joined with the Australian troops before heading for Colombo in Ceylon. How impressive was our convoy, with all those great ships steaming along together escorted by destroyers, cruisers and that plunging grey Battleship, HMS Ramillies riding in our wake!

On arrival in Colombo the most conspicuous shoreline structure was a great notice proclaiming;

“CEYLON FOR GOOD TEA”

This notice has never been re-erected.

Page 2

After arriving in Suez, Egypt, we entrained for our main camp at Maadi. All New Zealanders will relate to Maadi, but when we arrived there were just a few tents in the sand, although the office block was a wooden structure. There was also a movie theatre that was eventually pushed to the ground by irate soldiers when the projector kept breaking down.

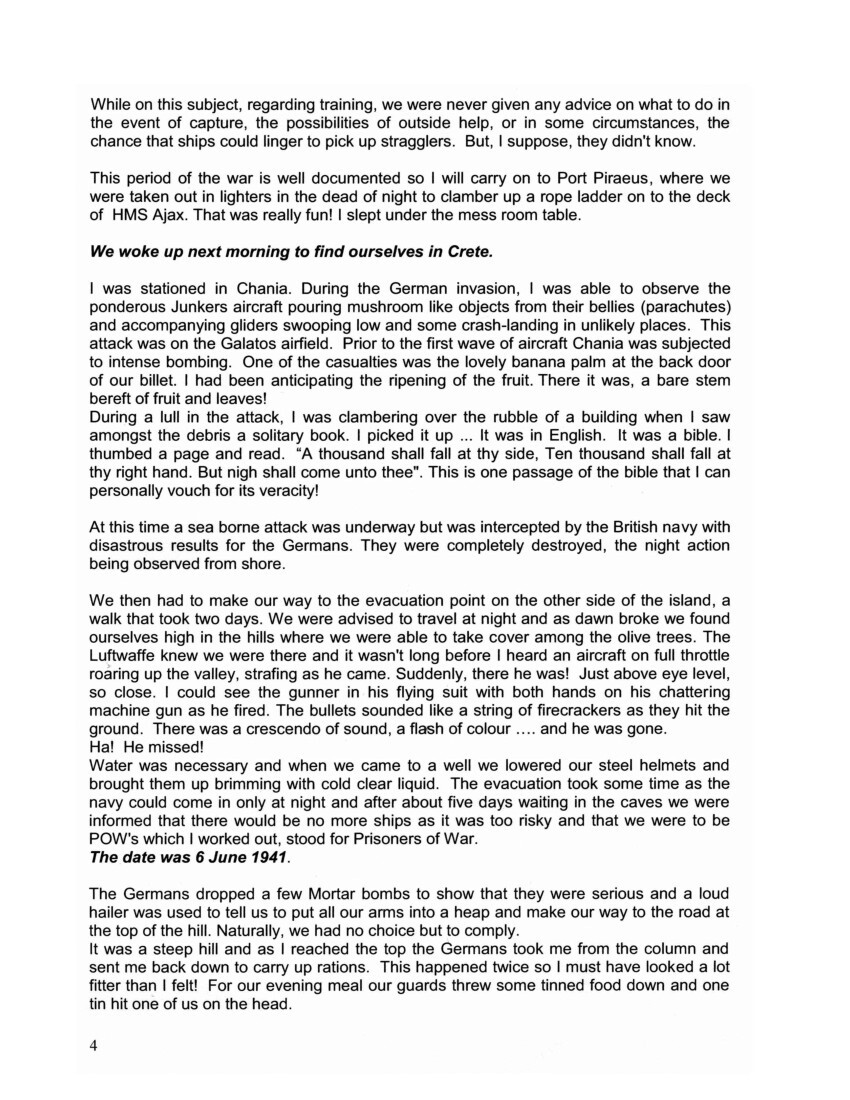

The role of my Company was traffic control on motorbikes. Once I had the pleasure with a fellow rider, of escorting Anthony Eden to the outskirts of Maadi. His chauffeur pressed us to go faster, which we did.

We enjoyed our time in Egypt with the warm weather and manoeuvres in Northern Africa.

We spent some time on duty in Cairo.

We visited the great pyramids and observed the Nile River boats and all the activity.

After a period of time we were granted a holiday in Palestine which once again revealed a very different lifestyle and culture. Our New Zealand accommodation in Jerusalem was opposite the grand King David Hotel. This was later bombed by terrorists in July 1946.

On the beach at Tel Aviv there were wrecks of two ships. These belonged to Jewish people who were not permitted to land and in desperation they drove the vessels ashore.

After a further period back in Egypt, the orders came to prepare to move to Greece.

On our voyage we encountered high winds with some snow, a faulty rudder, and high seas but all was forgotten when an issue of rum was made to all hands. After a stop in Athens we made our way over Mt. Olympus on our motorbikes and on to Salonika in Northern Greece. The Greek people were wonderfully hospitable and loyal to the end as all Kiwis will testify. During the retreat I was stationed at the main crossroads in the centre of Larissa. This was at a time of intense bombing and there were few pauses between attacks. When there were, I wandered down the main street and it was very strange to find that I seemed to be the only inhabitant. All the shops were still open. There wasn’t a soul in sight! I walked into a music shop, picked up a violin and wished I could play and then returned to my post. Somehow I had come across a large box of figs. As each truck passed I threw them packets of figs.

I was soon joined by my friend, Reg Winstanley, who was from Nelson. He too had been wandering the empty streets and found himself in the local bank. There was money in abundance and in answer to my unspoken query he told me that if he had taken any, he would have just been tempting providence.

The following night we worked together directing the traffic past dangerous shell holes until dawn. On the next day on our journey south we had to spend a night near a stream on the other side of a ploughed paddock. During the night it rained causing the field to become a muddy morass.

Photo caption – Mounted on my BSA in the desert.

Page 3

By the time we reached the other side the mud had so packed around the wheels of the bikes that it was impossible for them to revolve. The only remedy was to hack the mudguards off and continue without them until we arrived at the next gathering point. This was the last I saw of him. Win was a close friend and we had been together since our days at Trentham. As we evacuated Greece some ships were sent to Crete and others to Alexandria. We were on different ships!

It was Win who was with me when we holidayed in Palestine and other excursions and I still have good photos of him. He was with the Division when they were fighting in Libya but was killed at Sidi Rezegh. He was awarded a Military Medal for his bravery and now rests in the El Alamein Cemetery.

It was then decided that the army would be diverted to a coastal road that would take them through Lamia. This was a big move and no way would they leave it in the hands of a mere Lance Corporal! Consequently, General Freyberg arrived with Captain Robin Bell to make sure that all went to plan. After discussing the best way of making the change (my role was to listen) the General turned to Captain Bell. “Now, you will need some rations. Here are two packets of biscuits. Will that be enough?” Oh! Thank you Sir, I’ll be able to last a week on these! Robin needn’t have worried. I had plenty.

Robin was deprived of sleep at this time so he had a short sleep in my bed which was in a nearby bicycle shop. The blankets were a bit damp from the previous day’s rain.

Robin’s wife was a close friend of my sister and on our return to Hawkes Bay we both recalled those times.

We made our way south and eventually arrived at an embarkation point at Port Piraeus, Athens. Here, the engineers were busy making all machinery unusable to the Germans by draining the motors of oil and running them until dry. It took about ten minutes. I helped by shooting holes in the petrol tank of my motorbike. All I could do was to make great dents without penetration as my bullets were machine gun size and only operable because I had pinched the rims to make them fit the calibre of my revolver. The reason? The issued bullets, six of them, were lead-nosed and contrary to the Geneva Convention, hence my rejection of them. It is hard to believe that in all our weeks of training we were never shown how to fire the pistol we were issued with.

Photo caption – With Win (Reg Winstanley) on leave

Page 4

While on this subject, regarding training, we were never given any advice on what to do in the event of capture, the possibilities of outside help, or in some circumstances, the chance that ships could linger to pick up stragglers. But, I suppose, they didn’t know.

This period of the war is well documented so I will carry on to Port Piraeus, where we were taken out in lighters in the dead of night to clamber up a rope ladder on to the deck of HMS Ajax. That was really fun! I slept under the mess room table.

We woke up next morning to find ourselves in Crete.

I was stationed in Chania. During the German invasion, I was able to observe the ponderous Junkers aircraft pouring mushroom like objects from their bellies (parachutes) and accompanying gliders swooping low and some crash-landing in unlikely places. This attack was on the Galatos airfield. Prior to the first wave of aircraft Chania was subjected to intense bombing. One of the casualties was the lovely banana palm at the back door of our billet. I had been anticipating the ripening of the fruit. There it was, a bare stem bereft of fruit and leaves!

During a lull in the attack, I was clambering over the rubble of a building when I saw amongst the debris a solitary book. I picked it up … It was in English. It was a bible. I thumbed a page and read. “A thousand shall fall at thy side, Ten thousand shall fall at thy right hand. But nigh shall come unto thee”. This is one passage of the bible that I can personally vouch for its veracity!

At this time a sea borne attack was underway but was intercepted by the British navy with disastrous results for the Germans. They were completely destroyed, the night action being observed from shore.

We then had to make our way to the evacuation point on the other side of the island, a walk that took two days. We were advised to travel at night and as dawn broke we found ourselves high in the hills where we were able to take cover among the olive trees. The Luftwaffe knew we were there and it wasn’t long before I heard an aircraft on full throttle roaring up the valley, strafing as he came. Suddenly, there he was! Just above eye level, so close. I could see the gunner in his flying suit with both hands on his chattering machine gun as he fired. The bullets sounded like a string of firecrackers as they hit the ground. There was a crescendo of sound, a flash of colour…. and he was gone.

Ha! He missed!

Water was necessary and when we came to a well we lowered our steel helmets and brought them up brimming with cold clear liquid. The evacuation took some time as the navy could come in only at night and after about five days waiting in the caves we were informed that there would be no more ships as it was too risky and that we were to be POW’s which I worked out, stood for Prisoners of War.

The date was 6 June 1941.

The Germans dropped a few Mortar bombs to show that they were serious and a loud hailer was used to tell us to put all our arms into a heap and make our way to the road at the top of the hill. Naturally, we had no choice but to comply.

It was a steep hill and as I reached the top the Germans took me from the column and sent me back down to carry up rations. This happened twice so I must have looked a lot fitter than I felt! For our evening meal our guards threw some tinned food down and one tin hit one of us on the head.

Page 5

The guards who were good Austrian soldiers were most concerned and ensured he had extra rations. A night under guard and then the long trek back to the camp. It was hot by day but cold at night but I was fortunate in finding a stoney culvert where I could shelter from the heavy dew.

The end of the next day brought me to our destination and near the entrance I spied a soldier asleep under a large blanket. I eased half the blanket from him and cuddled up for the night. He was still asleep when I woke in the morning so I tucked him in without him being aware of my presence.

Now began a different and not very pleasant period of our internment. We were in tents on the shore of the Mediterranean and conditions were basic. The latrines consisted of shallow trenches in the sand and the roar of flies, when disturbed, was thunderous! Although we were able to swim each day to maintain cleanliness, it wasn’t enough to stop lice from causing an annoying rash around my waist although this was probably exacerbated by dietary problems.

After a few weeks we were taken by ship to Greece. This ship was normally used as a coal carrier but there was plenty of room for us in the holds. However we were allowed to climb out on to the decks once we entered the shelter of the Greek mainland. To combat the menace of lurking submarines we hugged the coastline all the way to Salonika, Northern Greece, so close that on one still morning I could hear the strains of a flute wafting over the tranquil waters. Was the player a shepherd tending his flock, or perhaps an Olympian sprite sending a message of peace? It was a moment for reflection and I made the wish that one day in the future I may be able to retrace this journey in more congenial circumstances. A wish that was unfulfilled!

After disembarking we were marched through the town and through the ancient Grecian city wall to a nearby compound where conditions were very poor. Rations were very meagre and berri berri and jaundice were common complaints.

This camp was staffed with younger Germans, Hitler Youth, who were trigger happy. Too close to the wire and you risked being shot. One New Zealander, Joe Bartosh, trying to find his way at night in the toilet, struck a match. The guard outside saw the forbidden light and dropped a hand grenade through the window! He died. Previously Bartosh and I were together on the deck of the HMS York, a warship that had been seriously bombed and then run aground in Souda Bay.

We were there as part of a small working party and at one stage he handed me a piece of dried withered bread. I was surprised at his generosity until I realised he had false teeth. I bit into it and my teeth squeaked. I was soon able to return the favour by offering him a portion of rice that I’d found on the deck. Incidentally, the main turret gun was still operable throughout the invasion and during the night fired over our heads. There was a flash of light followed by a great bang! and then a whoosh whoosh as the shell passed overhead.

From here we were herded into cattle trucks (8 horse, 40 hommes) for the eight days journey to Germany. It is interesting to note that when we first boarded, many were on the verge of dysentery but after a few days, when we were let out alongside the tracks, the opposite occurred and there were lines of men all trying to do their best.

Page 6

A town in Bulgaria was our first stop and we were met by ladies from the Red Cross, all dressed in blue and white striped uniforms and looked so beautiful and CLEAN! They gave us a tin of meat and a loaf of bread to last us for the rest of the trip.

Eventually we arrived at Stalag VIIIB near Lamsdorf in Czechoslovakia.

The workings of this Stalag.

Our first entry meant we had to have all our hair shaved off and all our clothes were put through a delousing steam bath. Unfortunate, indeed, were those who forgot to take their boots out! We also had a shower and then photographed, given a number, mine was 21864. (For some reason my photo was taken later and by then my hair had regrown.) We were also given a pair of wooden clogs and a square of cloth in lieu of socks. Clogs were good to wear when the ground was covered in snow.

After a while we all lined up for a ration of soup. It consisted of fish and potatoes, lentils and peas. At one stage a ripple of excitement went down the queue when it was learned that some lucky one had a whole potato dropped in his soup. A WHOLE POTATO! I, at this stage, was succumbing to jaundice, a lack of the required vitamins, and was put in hospital for a week. On discharge, I received a Red Cross parcel with a tin of condensed milk which I enjoyed too much. This made me all yellow again but it lasted only a day so the rest of my hospital stay was a delight.

The Stalag was divided into several compounds of long sheds housing 200 men with a 100 men in each barrack with a division between the two supplying cold water for ablutions and washing. There were several rows of bunks, three beds high, with straw paillasses [palliasses] and wooden bed boards. Due to the shortage of wood these boards were gradually used for brewing the all-important cup of tea and the Germans replaced them with fencing wire. After a period of time the straw disintegrated and the wire was clearly visible . . . but we slept well.

We were able to shower every 11th day. We all stood under a spray head waiting for the hot water to be turned on. After a short time it was turned off. We then busily lathered ourselves (or did our best with the weak German soap) until the water was turned on again for the final rinsing. The toilets were alongside, a building with 40 holes, no partitions. The whole complex was surrounded with barbed wire, with machine gun posts and searchlights at intervals around the perimeter. Occasionally a guard and dogs patrolled at night. So we were well looked after!

There were about six or seven thousand men in the camp with many more in the attached working parties. An issue of camp money was made but not highly valued but could be used for some purchases. Cigarettes were the main source of currency. Two cigs for a haircut. A few small stalls were set up. In many ways it was like a small town, with several orchestras, brass and jazz bands and drama groups. There was also an outside group who regularly visited all the camps and presented very professional plays and concerts.

There were also units where one could go to further their education in any language or subject. Rugby was played on occasions and I am happy to report that the Kiwis usually won but not in soccer!

Page 7

Once a year there was a display of art. This show was unbelievable! To see all the articles made from basic materials was astounding. There was a working steam engine made from jam tins, handsome clocks, a superb chess set carved from toothbrush handles, by a craftsman obviously, and finger rings made from toothbrushes with a photo of their loved one inserted. Working windmills and other devices all made from tin.

In the art world I clearly remember a painting of a Canadian who had been captured in Dieppe. It depicted his rugged face, clad in a balaclava with hands outstretched as he told his story. Linking his wrists was a chain. Apparently at some camp in England, Germans were subjected to this treatment and in retaliation it was decreed that we should also be handcuffed. Hence the reason for the chain. The chains were no deterrent. They could be unlocked with a sardine key and when the guards came to put them on they found they were working on an endless queue. They soon gave up.

Another example of the use of tin was when a glass window was shattered. Every piece was collected and edged into a piece of metal, making an intriguing mosaic artwork.

Cooking some food from our Red Cross parcels and the brewing of tea was done by the use of a blower, an apparatus with a fan housed in a circular container, a cocoa tin leading to a firebox and two pulleys made from cotton reels with boot laces as belts. This was most effective and needed the minimum of fuel. In Italy, they used what we now know as a thermette.

The rations supplied were only just sufficient to maintain life but the wonderful Red Cross parcels, which we received once a week, enabled us to keep the pangs of hunger at bay, although new prisoners found it tough, until their stomachs contracted. Red Cross parcels came mostly from USA, Canada and Britain with the occasional one from NZ. The English parcel contained 1/4 pound of tea, tinned creamed rice or beans, packet of biscuits, tin of margarine and condensed or powdered milk. The American parcels were noted for the quality milk powder called Klim (milk spelt backwards) with tinned meat, cracker type biscuits, butter, jam, chocolate and other goodies.

In the earlier years German transport was unaffected by the war but as the Allied attacks came closer and destroyed the railways, so our parcel supply was interrupted and issues became fewer.

The camp rations consisted of hot tea made from mint, or an ersatz coffee made from burnt maize or perhaps one made from herbs. Not unacceptable, but it was often used for shaving. This would arrive about 9 am and towards midday soup made with turnips (a mainstay) and potatoes, or fish and cabbage and any other available vegetable. Sometimes a good pea soup and mostly all nutritious.

In the late afternoon we received a loaf of bread, a small portion of meat (horse meat) and a spoonful of jam. This was often beautiful strawberry jam as they grew wild on the nearby hills. The bread was divided into six pieces, about the width of a matchbox, or eight pieces when transport was disrupted. A pack of cards was produced and a card placed on each piece. The corresponding card dealt to the recipient was his piece. That way, no argument!

Page 8

As food often had to be divided it was necessary to have a “Mucker In”. That is someone to share and cook with. Most were in pairs but some were foursomes. My mucker was Joe Kellor from the Nelson area. He was a fairly fussy eater and I remember him giving me the beans from his soup because they were fermented. One day, he felt terrible, with a bad cold, and decided to visit the doctor. He did, and was diagnosed with tuberculosis and put into hospital and then repatriated through Sweden back to NZ. He died when he returned.

After that I went on a working party where we were employed in the production of wood wool. This was in the hills, and I think that the new environment enabled me to prevent the onslaught of TB as in later years I was told there was scarring on my lungs. Lucky me!

Back to the Stalag! The soups were always delivered in large keebles or urns and as we queued we received our allotted ration which was the equivalent of a jam tin. Afternoon food was collected by a delegated party. We were often given a “fish cheese”, which was good when it was fresh but if older it was slimy and foul smelling. The bread was from rye and long lasting as the date stamped on it showed. Weeks old, and occasionally mould showed in the cracks. But it was nutritious and kept us going. Except for the odd camp search when we had to stand out in the cold for nine hours, they left us alone.

As Stalag V111 grew and was becoming unmanageable, it was decided to change the name to 344 in 1943 and establish two smaller Stalags. One of these was in Teschen, Poland in which I was placed. It was a coal mining district with plenty of coal to keep us warm. Alongside was a Russian block and frequently we saw the carts carry out the dead. The Russians were not party to the Red Cross so had a very hard life with typhus rampant. When we were being deloused in the early days, one of the group had the clothes of a Russian that he had kept for show. It was so covered in lice that spoonful’s at a time could have been removed from the seams.

It was at this time that the Allied forces were building up their armies for invasion but those fighting in Europe were getting very impatient and accusing Britons of not doing enough. The Soviet soldiers I spoke with declared “England is fighting the war! With Russian blood! At that time, it was hard to argue. At night our room was cosy but fairly cramped.

Photo caption – Fellow POW’s at E250 Sudetenland work camp

Page 9

Our Red Cross parcels were kept by our respective beds and we were surprised to find that food would disappear during the night. We worked out that a Ruski was sneaking in and spooning the condensed milk as we slept, leaving the empty tin! In the room was a metal stove for heating and would at times be very very hot. One night there was a cry. “The Ruski’s in the room”. This was quickly followed by a scream of agony that just made us freeze in our tracks, as the poor bloke ran into that almost red hot stove! He was found later in the wash house.

From here I went to a military warehouse where flour was stored. It had been brought from the Ukraine and was in beautiful linen bags which we purloined and used for sheets. These bags had to be turned every now and then, to stop the mould. We used to make long narrow bags to hang down each trouser leg and filled them with flour! We had a professional baker in our party and it was here that I learned to make a bread roll and to this day I still follow his instructions.

As the Russians advanced we were returned to Stalag V111B.

Each year we told each other that we would all be home for Xmas and there was always someone who had the latest news which was always encouraging. “What’s the griff?” was the question asked when more news was required.

On the wall of the main barrack room was a large map showing the advance of the Allied Army depicted by a line of red string strung round pins placed on the various cities so we always kept up with the latest news. This was in agreement with the Germans as long as it showed where the troops were according to their own papers….but we knew better and the guards asked us about the true position.

Then, during the winter of 1945 we were aware of the constant rumble of the guns on the Russian Front. They were coming! The Germans must have valued our company as they decided to move us out to “safer” places, but we had to walk.

So began our march in early February (known as the Death March or Great March West).

We left in the late evening at the end of a very cold day. As we made our way and night fell, the conditions worsened and walking become difficult. The ground was frozen and every now and then someone would fall. At 3am we arrived at a large barn where we had to sleep for the rest of the night. It got so full that there was no room for anyone else to get in. We had to sleep with our boots on as they were too frozen to get off. So that was the first day and we marched through the depths of winter to the slush of Spring, enjoying the farmers’ turnips or potatoes when available. Turnips were ok eaten raw, but just try potatoes!

I can remember surprising little of the march but etched in my memory is an occasion when one wintry day, a column of Russian prisoners stood aside to let us through.

As we passed I raised my head to see this line of inscrutable Mongolian-featured faces observing us closely. Some were black skinned, some very oriental looking and all with their highly padded clothing and headgear. As I looked, between our faces, the snow appeared to be driven almost horizontally. I can still picture that moment!

Page 10

After marching for about 6 weeks we were passing a farmers shed with a pile of turnips outside which attracted some prisoners, and inside was a heap of sweet smelling hay. I knew all about hay so I quickly dived into it and allowed the guard, unknowingly, to lock me in. I had the loveliest sleep and after waking, waited for the farmer to open up. As I walked out I wished him a very good morning. He requested I wait, but I tarried not.

I had only two or three days of freedom before the Gestapo picked me up and not knowing what to do with me, put me in a jail full of, I think, political or civilian prisoners. I was the only soldier and was searched before being allocated Celle zwelf . . . Cell twelve.

It was spotless, with green paint to head height and white above, and a flush toilet, hand basin and a low bed with one blanket. A high barred window showed a patch of blue sky. I used to watch the American Flying Fortresses, escorted by their fighters, as they flew by on their path of destruction. The whole sky became criss-crossed with vapour trails turning a clear morning into a cloudy one. Later mission accomplished, they steadily returned. Back to their bacon and eggs!

As my stay was expected to be of short duration I was allotted “punishment rations” but once they realized that I was here for a longer period, I was given the normal amount of food. This consisted of a small portion of margarine, jam, bread and a weak ersatz soup that was so thin it was hardly worth licking the plate…but the exercise was good! Saturday was the big day. We got six or seven small potatoes, boiled in their skins. When the warder came to collect my plate he seemed surprised. “Where are the peelings?” I looked at him and said “There are no peelings.”

Each evening we had to report outside the cell. In my case Celle zwelf, ein man! It looked like a scene from a movie as I looked down on the rows of inmates, men and women.

After a period of time I was given work with a group in a nearby room. It was here that one day I felt a small package pressed into my hand. Once back in my cell, I opened it to find a thin little cigarette, one match and a tiny piece of striking paper. This called for strategy! That evening, when the guards had all retired for the night and the complex was quiet, I placed the paper carefully on the floor, readied the cigarette, and with the one match poised over the paper, I struck! The tension was electric! The match burst into flame and I was able to enjoy my smoke but after the first puff my head was so dizzy that I had to lie down to finish it. Moral. Don’t smoke!

My job was to paint glue on gas mask rings. I knew that I should not be there, but as the Gestapo had put me in, the military were unable to get rid of me. But, one day, after I had been there for six weeks, the Governor of the Prison arrived and I explained my predicament. He was most concerned and arranged that I move the next day. He couldn’t understand my German but I had a Dutch friend who understood my accent and translated my words.

The next day I was marched to a nearby Russian work party. As I entered the quarters I was aware of a strong pungent smell. They were smoking shavings of pine tree wrapped in newspaper. Every now and then the cigarettes would burst into flame and they would wave them frantically to extinguish them. They were lying on straw on the floor, all padded up in their winter clothing. There was a partition between their piles of straw and mine so I was content to have my own patch.

Page 11

Alongside our area was a small plot of land which was to be planted in potatoes and I was detailed to do the planting. This I did and after pointing out that there would be a shortfall of seed, and that more would be required, I finished the job. That night I had potatoes for tea and the problem was how to cook them. This was solved by threading them on a piece of wire and lowering them into the glowing coals of the heating stove. True, they did have a very charred look but they were all right inside and I was able to share them with my new-found friends. I had never noticed before that Russians had such black lips!

Our job was to build tank barricades using tree trunks. We would line up and count “ras, rah, tree,” and all lift together. After six weeks on poor rations, I didn’t have much strength but once I learned the Russian word for four, I found the going much easier.

As time passed, once again we were ordered to march, but this time it was of shorter duration.

NB: there is a gap here in my memory regarding the exit from the Russian working party and my arrival at the castle. I cannot remember the name of the location of the castle but know that it was west of Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia.

I still had not met up with any fellow kiwis.

It wasn’t long before we arrived at a fairy-tale castle. It was beautifully situated on a rocky hill surrounded by forest and the towers gleamed in the sunshine. It was easy to imagine the bowmen firing their arrows from the slots. It was occupied by mostly American and some British prisoners of war.

Previously, it had been occupied by Jewish detainees and there was wire netting placed around the ramparts to stop them from jumping to their deaths. We were housed in the lower rooms and it was from this camp that we commenced our final march. As we made our way down the country roads, littered with the goods of refugees, the Germans guards were no longer with us and we found ourselves on our own.

Then I realised the war must be over.

There were also streams of ex-combatant Germans making their way home in the opposite direction. Noticing a water filled quarry, I knew that it would be used to get rid of unwanted arms. On investigation I found arms of all sorts and collected half a dozen pistols. Smith and Wesson’s, Lugers, P38’s, and others. Noting a group of farm buildings, I approached and found a good sleeping place in the loft.

By morning I reflected that the pistols were not desirable in the world we hoped to live in so I left them in a little pile for the farmer to find when he next fed his cows.

I then turned my attention to the rest of the complex. There was not a soul to be seen, I opened a wooden door and found a room full of women and children all with a look of horror on their faces as they looked at me. There was a great sigh of relief when they saw who I was, and welcomed me saying, “Oh! Come in, we thought you were Russian.” This personifies the regard the Germans and English had for each other but as to becoming a successful enemy, I felt an abject failure.

Page 12

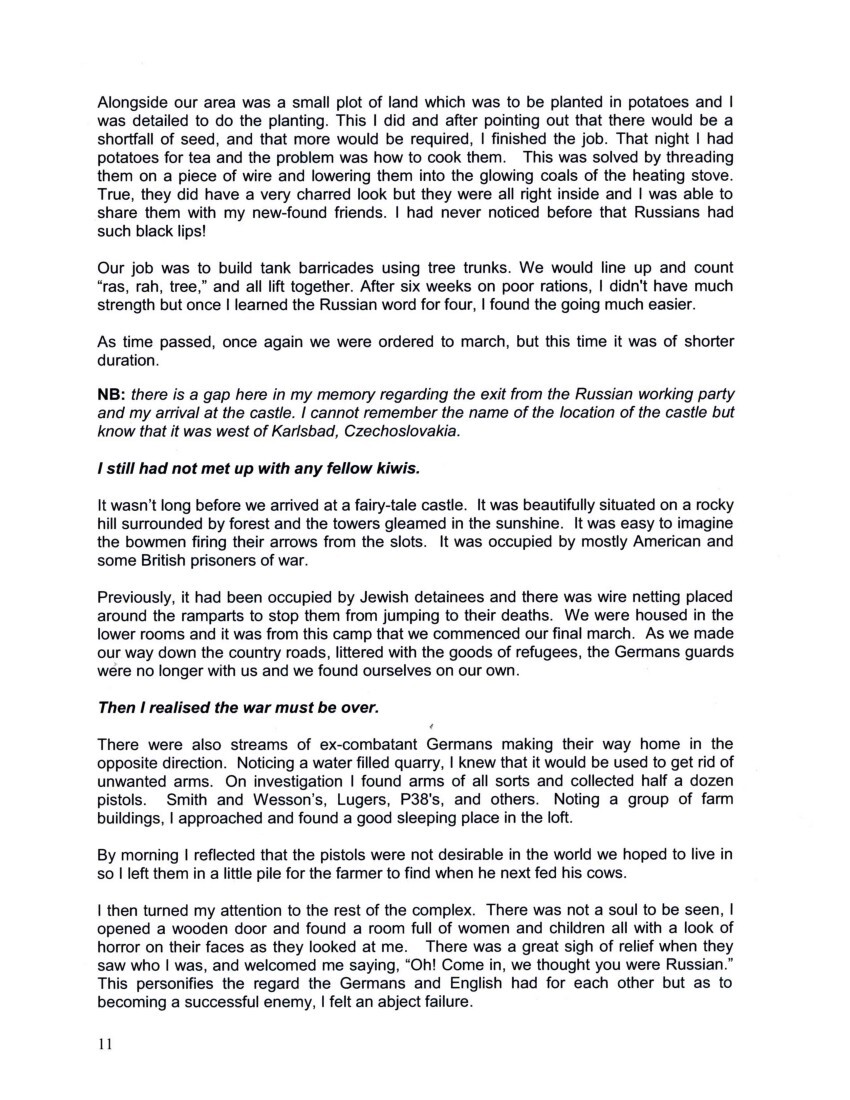

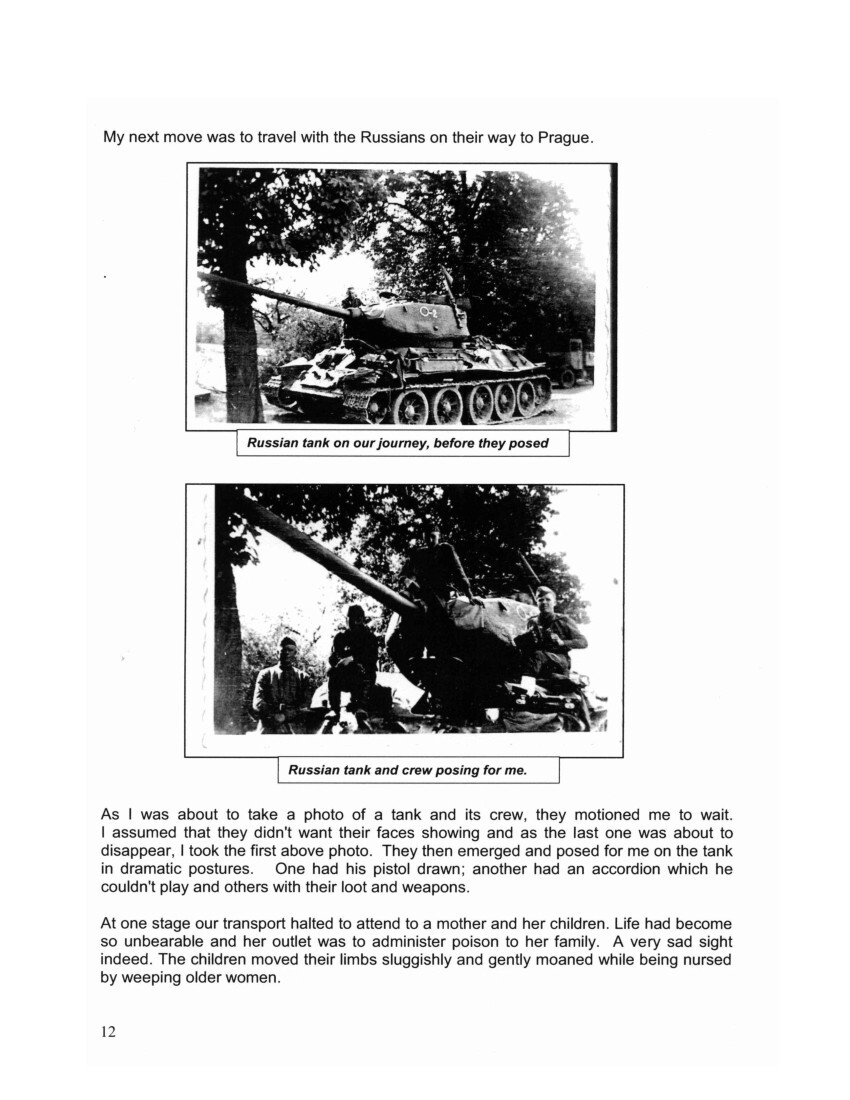

My next move was to travel with the Russians on their way to Prague.

As I was about to take a photo of a tank and its crew, they motioned me to wait. I assumed that they didn’t want their faces showing and as the last one was about to disappear, I took the first above photo. They then emerged and posed for me on the tank in dramatic postures. One had his pistol drawn; another had an accordion which he couldn’t play and others with their loot and weapons.

At one stage our transport halted to attend to a mother and her children. Life had become so unbearable and her outlet was to administer poison to her family. A very sad sight indeed. The children moved their limbs sluggishly and gently moaned while being nursed by weeping older women.

Photo captions –

Russian tank on our journey, before they posed

Russian tank and crew posing for me.

Page 13

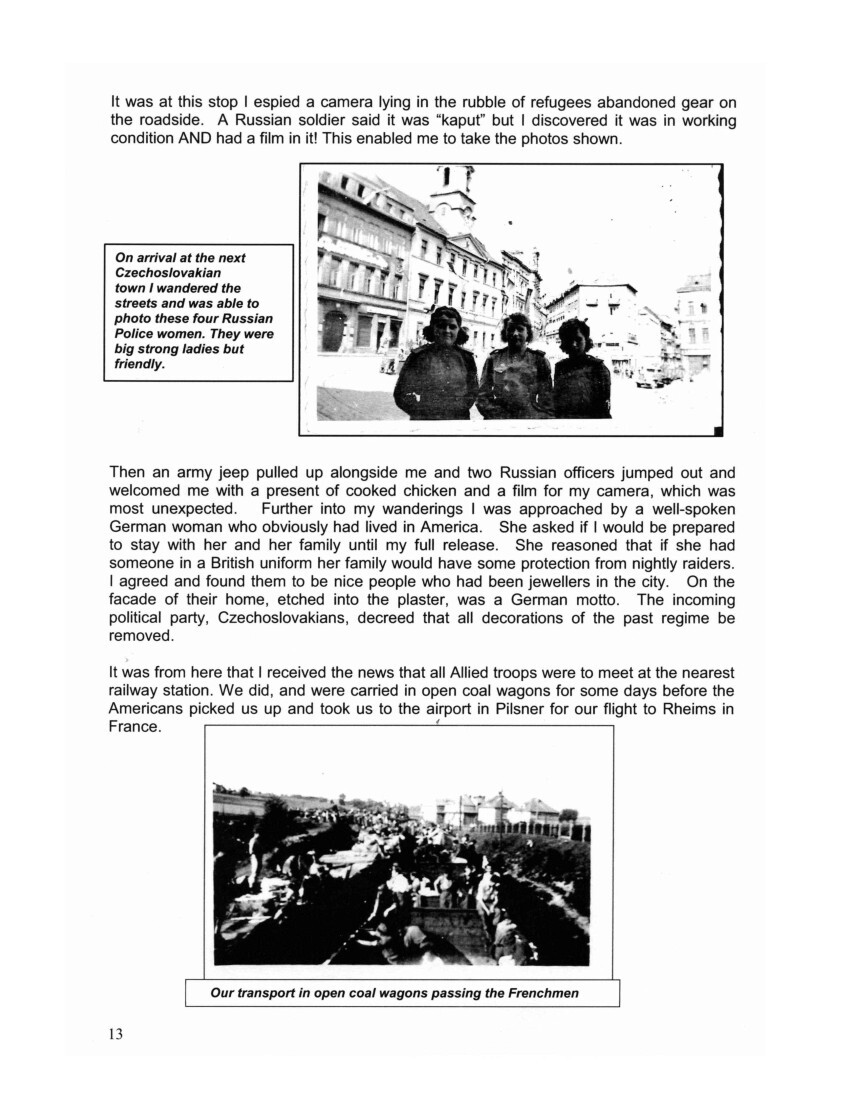

It was at this stop I espied a camera lying in the rubble of refugees abandoned gear on the roadside. A Russian soldier said it was “kaput” but I discovered it was in working condition AND had a film in it! This enabled me to take the photos shown.

Then an army jeep pulled up alongside me and two Russian officers jumped out and welcomed me with a present of cooked chicken and a film for my camera, which was most unexpected. Further into my wanderings I was approached by a well-spoken German woman who obviously had lived in America. She asked if I would be prepared to stay with her and her family until my full release. She reasoned that if she had someone in a British uniform her family would have some protection from nightly raiders. I agreed and found them to be nice people who had been jewellers in the city. On the facade of their home, etched into the plaster, was a German motto. The incoming political party, Czechoslovakians, decreed that all decorations of the past regime be removed.

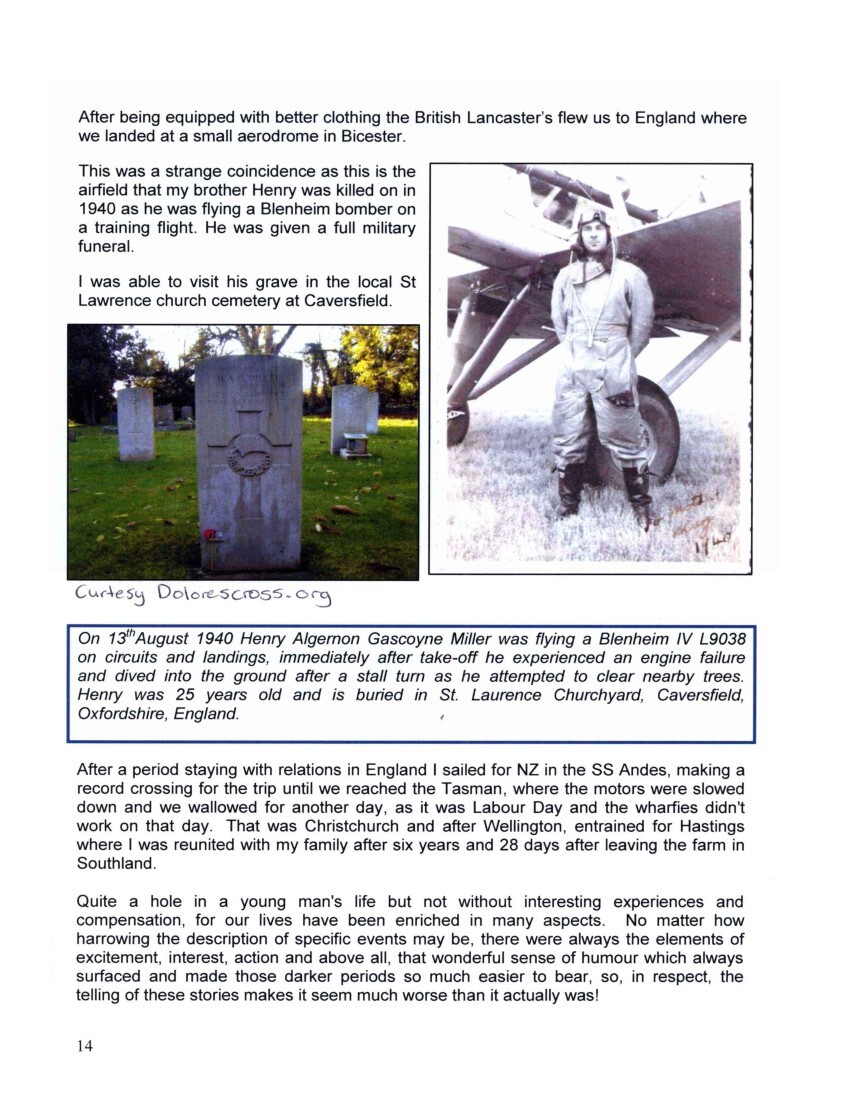

It was from here that I received the news that all Allied troops were to meet at the nearest railway station. We did, and were carried in open coal wagons for some days before the Americans picked us up and took us to the airport in Pilsner for our flight to Rheims in France.

Photo captions –

On arrival at the next Czechoslovakian town I wandered the streets and was able to photo these four Russian Police women. They were big strong ladies but friendly.

Our transport in open coal wagons passing the Frenchmen

Page 14

After being equipped with better clothing the British Lancaster’s flew us to England where we landed at a small aerodrome in Bicester.

This was a strange coincidence as this is the airfield that my brother Henry was killed on, in 1940 as he was flying a Blenheim bomber on a training flight. He was given a full military funeral.

I was able to visit his grave in the local St Lawrence church cemetery at Caversfield.

After a period staying with relations in England I sailed for NZ in the SS Andes, making a record crossing for the trip until we reached the Tasman, where the motors were slowed down and we wallowed for another day, as it was Labour Day and the wharfies didn’t work on that day. That was Christchurch and after Wellington, entrained for Hastings where I was reunited with my family after six years and 28 days after leaving the farm in Southland.

Quite a hole in a young man’s life but not without interesting experiences and compensation, for our lives have been enriched in many aspects. No matter how harrowing the description of specific events may be, there were always the elements of excitement, interest, action and above all, that wonderful sense of humour which always surfaced and made those darker periods so much easier to bear, so, in respect, the telling of these stories makes it seem much worse than it actually was!

Photo caption – Curtesy [Courtesy] Dolorescross.org On 13th August 1940, Henry Algernon Gascoyne Miller was flying a Blenheim IV L9038 on circuits and landings, immediately after take-off he experienced an engine failure and dived into the ground after a stall turn as he attempted to clear nearby trees. Henry was 25 years old and is buried in St. Laurence Churchyard, Caversfield, Oxfordshire, England.

Page 15

One of my great regrets of the POW days is not keeping a book that the Germans produced showing photographs of the Battle for Crete. We were allowed to buy it with camp money and it was beautifully printed with graphic photos of the invasion. At the back were several blank pages which over a period of two years I filled with the signatures of men and their regiment or service they belonged to, one from each unit. I had the names of sailors from all the great battleships, destroyers, submarines and all the British Regiments and Airmen and the service in which they served. I learnt of so many famous names during my collecting and I still recognize many when they arise today. On the first day of our March I realized I could only carry the necessities and any surplus weight had to be jettisoned. The book was a heavy one so I tore the pages from it and carried them separately. I had them at the Craggy Range farm for many years but they had got tatty, and the indelible pencil was fading so they were discarded. What a wonderful record it would have been today!

I’m sure all other Service Personnel so much appreciated the wonderful help that all New Zealanders gave in the assistance of our rehabilitation.

Their generosity with low interest loans for farms, homes, businesses and other help has not been forgotten.

I would like to meet up with other First Echelon men but there are not too many of us left.

NEW ZEALAND ARMED FORCES MD387A

STATEMENT OF SERVICE

NEW ZEALAND DEFENCE FORCE

of Gascoyne Francis MILLER

No. 5851 Rank: Lance Corporal

Force: New Zealand Army

Served Overseas

5 January 1940 to 24 October 1945

…to…

…to…

Served in New Zealand

17 October 1939 to 4 January 1940

25 October 1945 to 21 February 1946

…to…

Date of Discharge: 21 February 1946

Total Service: 6 years 128 days

Medal Entitlement: 1939 – 45 Star

Africa Star

War Medal 1939 – 45

NZ War Service Medal

DATE: 15 June 1992

Defence Force Headquarters

Wellington

NEW ZEALAND

SE Tyler-Wright

for Chief of Defence Force

Page 16

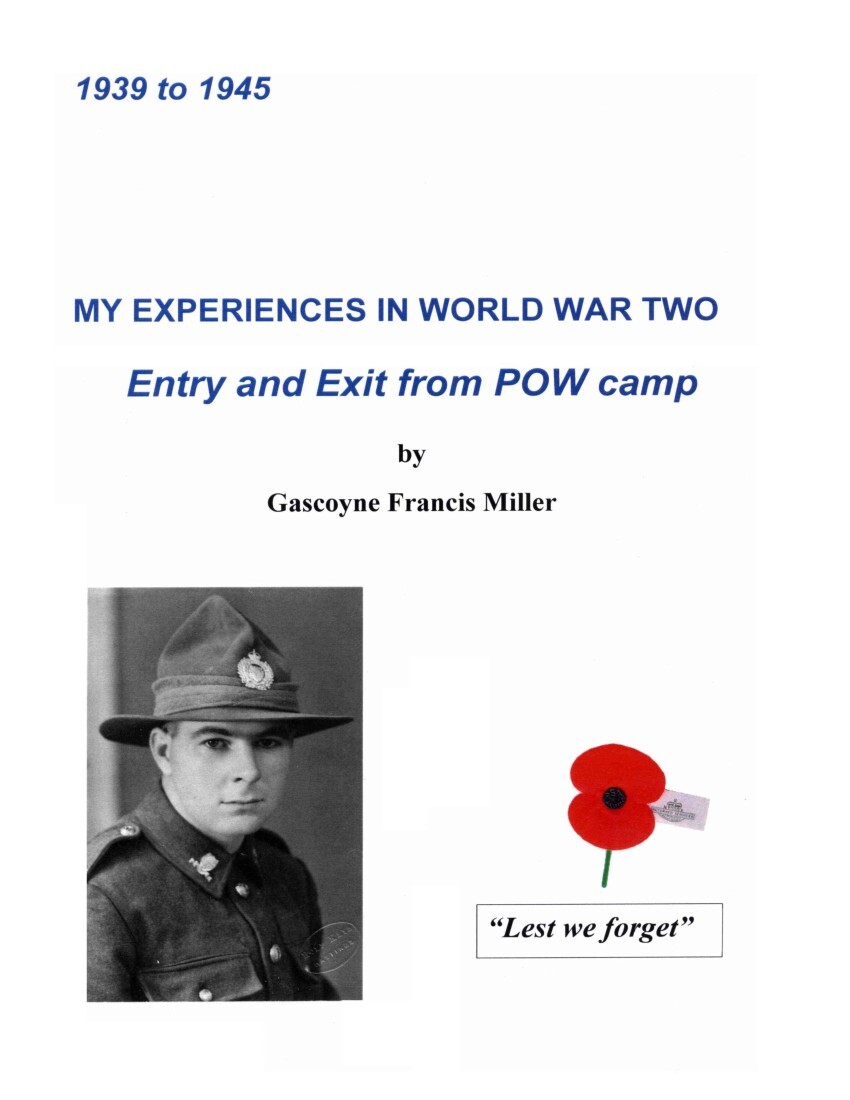

Incidentally, I am 94 years old and as I write this story on my Ipad [iPad] I reflect that so much time has passed since my use of a slate and pencil in my early school days. My daughter, Cathy McGregor, assisted with document layout, editing and inserting the photos.

I have a beautiful leather bound photo album which I bought in Egypt, filled with photos of my time overseas.

Gascoyne (Jim) Miller

153 King Rd. Meeanee R.D.3, Napier, New Zealand.

Phone 06 8344 652

[email protected]

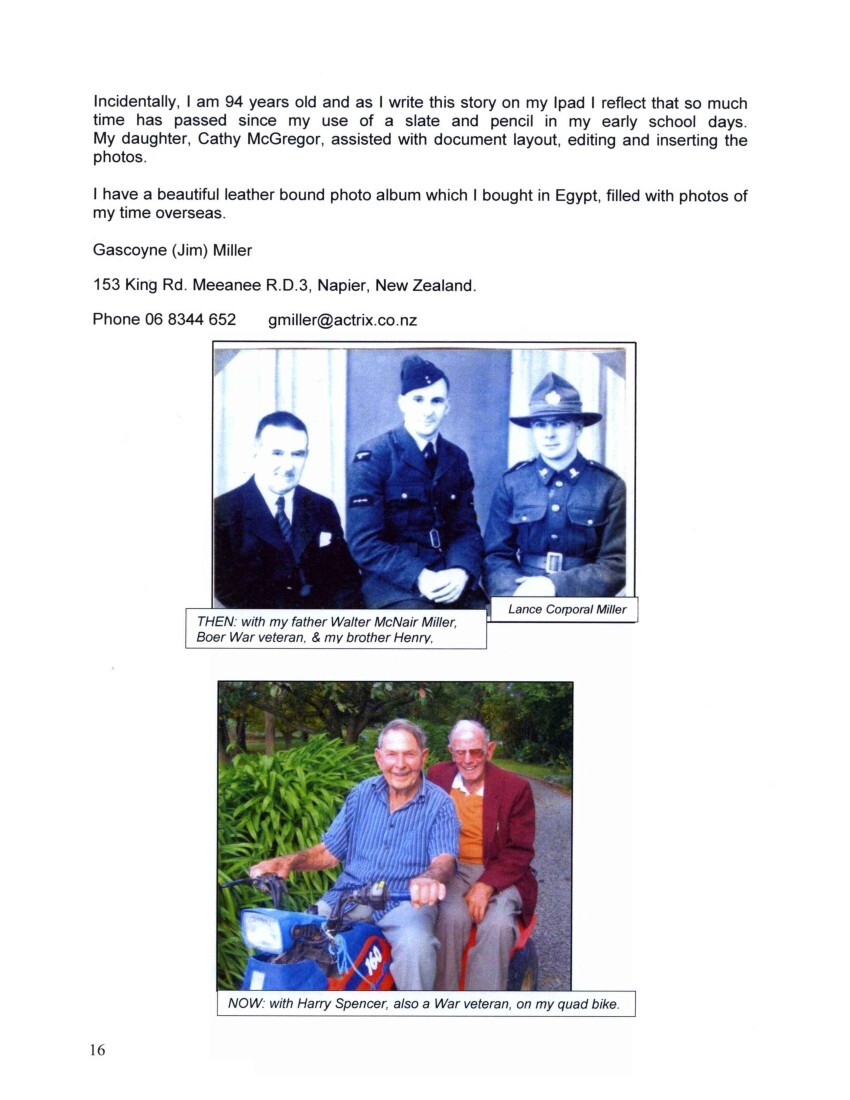

Photo captions –

THEN: with my father Walter McNair Miller, Boer War veteran, & my brother Henry.

Lance Corporal Miller

NOW: with Harry Spencer, also a War veteran, on my quad bike.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Tags

Format of the original

Typed documentDate published

August 2012Creator / Author

People

- Joe Bartosh

- Captain Robin Bell

- General Freyberg

- Cathy McGregor

- Henry Algernon Gascoyne Miller

- Harry Spencer

- Walter McNair Miller

- Reg Winstanley

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.