- Home

- Collections

- NEWSON JR

- Local History

- Naming of Napier, The

Naming of Napier, The

Page 2

The Naming of Napier

The Maori name of the district now covered by the City of Napier was Ahuriri. This is said to mean “a rushing out of water”, and may refer to the channel through which the waters of the lagoon – now mostly dry land – rushed out at low tide. This the early Europeans converted into the odd name of “Howready”.

Before 1840 when the whole country became a British colony, the only Europeans were the whalers, with their whaling stations all up and down the coast, from the Mahia Peninsula southwards. After 1840 occasional traders would come up from Wellington, exchanging goods for the pork and flax supplied by the considerable Maori population.

The first white family to come into the district was the Colenso family – William Colenso, his wife Elizabeth, and his little daughter Frances – when Colenso came to establish a Mission Station at Waitangi, a little to the south of what is now Napier. This was at the very end of 1844.

In his diaries for 1846, Colenso mentions a trader who had come and seemed likely to settle. This is presumed to be Alexander Alexander, who married Harata, a Maori girl of a chiefly family, and took up land at Wharerangi, where his grave may still be seen on the hillside.

In January, 1849, the first sheep came into what is now Hawke’s Bay, driven up from the Wairarapa by C. Northwood, F. J. Tiffen and E. Collins, with some Maori helpers. These men brought the sheep to Pourerere, and spread inland from there, leasing land from the local chiefs.

Towards the end of 1850 the first actual settler families arrived from Wellington, and built a house on the shingle spit which is now Westshore. They were the McKains and the Villers, who were inter-related, as the wife of William Villers was the sister of James McKain.

All this was very irregular, because by the Treaty of Waitangi nobody could buy or lease land directly from the Maoris. The Government had to buy the land, and then re-sell it to the settlers. So Donald McLean was sent by the Government to look into the question of buying land, and in November, 1851, Deeds of Sale were signed covering the Waipukurau Block, the Ahuriri Block and the Mohaka Block. A year or two later, after

Page 3

some surveying had been done, Alfred Domett was appointed Commissioner of Crown Lands and Resident Magistrate at Ahuriri.

Domett was one of those men of good education and some private means who came to this country in the early days of colonisation and took a leading part in its affairs. He had spent two years at Oxford, but left without taking a degree, and then he travelled for some time in North America and the West Indies. He qualified as a barrister, though he never really practised. His tastes were literary ones, and he had a circle of friends with similar interests, including the poet Robert Browning. In 1841 he decided to emigrate to New Zealand, intending to join a cousin who had settled in Nelson.

While Domett was on the way out his cousin was drowned in a flooded river, but Domett remained in Nelson, and soon became a leading figure in the new settlement. He was called to the Legislative Council by Sir George Grey, became Civil Secretary for the Colony, and then was appointed to Ahuriri, where he arrived at the beginning of 1854.

In the previous year New Zealand had been divided into six Provinces, and what is now Hawke’s Bay was part of Wellington Province. Therefore, much of Domett’s correspondence was with Dr. Featherston, Superintendent of Wellington Province. These papers are in the National Archives in Wellington, but the Hawke’s Bay Museum fortunately holds Domett’s letter-book as Resident Magistrate, which was found when the Courthouse was being renovated some years ago.

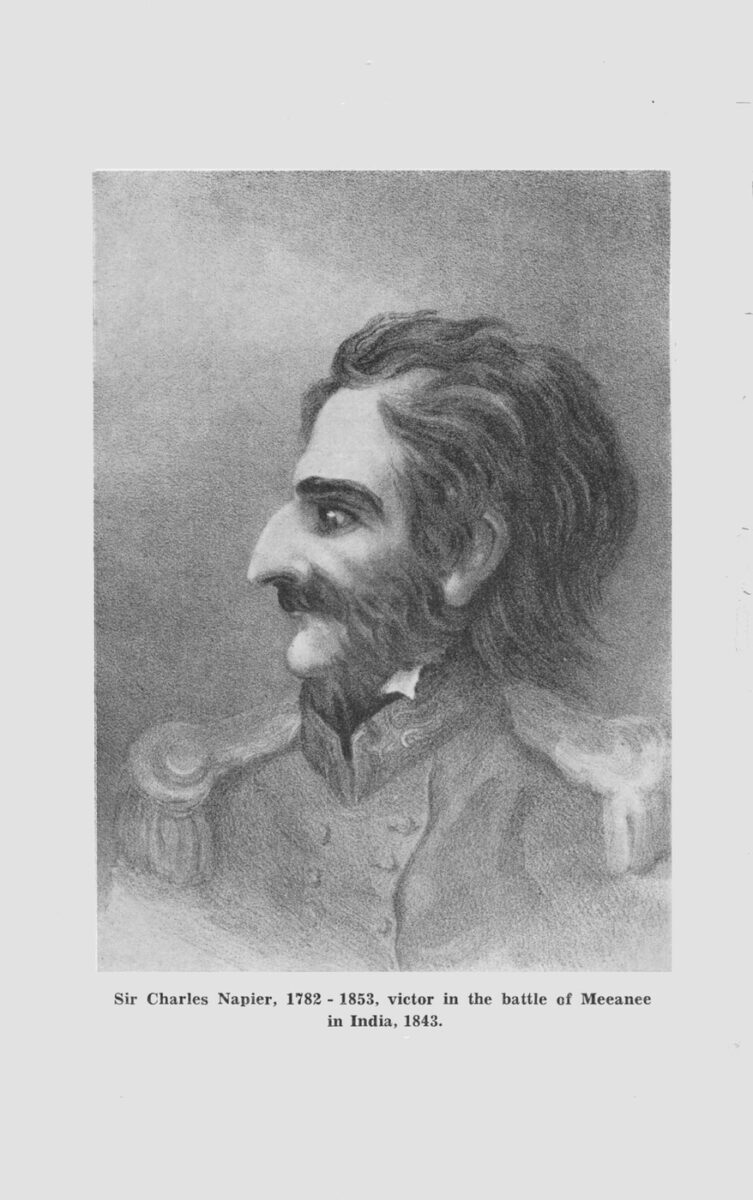

Soon after his arrival Domett wrote a letter to Dr. Featherston in which he described the district at some length. Then he goes on to say “One point remains, the nomenclature of the places in question. The native names in this district are particularly harsh, discordant to European ears or low and disgusting in signification. As almost all the inhabitants of this district united some time back in a memorial to the Governor requesting the principal town might be called after the great founder of our Indian Empire, Lord Clive, and as it appears that the Port Town can only be subordinate, I would propose that the latter should be named in commemoration of one of our greatest and best Indian Captains just dead – Sir Charles Napier. I have caused the subordinate names of streets etc., to be inserted in association with that most public-spirited benefactor of his country and trust that this step will accord with your Honour’s views upon this subject.”

Page 5

Sir Charles Napier served in the Army in India at a time when British influence was expanding there – something that naturally was not to the liking of many of the Indian Rulers. There was an attack on the British Consul at Hyderabad and to put an end to this Napier gathered together a small force, and at the battle of Meeanee defeated a much larger Indian force, so getting control of the important province of Scinde. This was in 1843. (The spelling of these names is that current in Domett’s time. The modern spelling is “Miani” and “Sind”).

In April, 1855, the first sale of sections took place in Napier. The schedule of sections and purchasers is given in the Wellington Provincial Government Gazette of July 16, 1855. The sections at what is now Westshore are listed first, and the sections on the hill and the small area of land at the base of it come under the heading of “Scinde Island”, so we know that Domett must have given the name of Scinde Island to the Napier hill, which at that time was like an island almost surrounded by sea and swamp.

In a later Gazette is printed a letter from Domett, in which he gives an account of the sale of sections and describes the lay-out of the town and his ideas for the naming of the streets.

“The names attached to the roads and streets have been given on the principle previously adopted and approved by Your Honour. The principal Town Roads and streets have been called by the names most prominent in British Indian history. As these were soon exhausted, I had recourse to the names of the most eminent men in literature and science of our day. The remaining roads are proposed to be called after the most celebrated English poets. It is better to have pleasing associations with the names of our roads and ravines, however unworthy they may seem of such distinguished ones, than to be constantly reminded of the existence of obscure individuals (ruffians possibly, and runaway convicts), whose names get attached to the places they happen to be the first to pitch upon, and almost render the places themselves distasteful, however favoured by nature.”

In this letter Domett refers to a map which he had sent to Dr. Featherson, and when it was realised that a copy of this map would be of great value in the study of the history of Napier an appeal was made to National Archives to see if the map was still in existence. After

Pages 6 and 7

No. Papers Date Receipt From whom received Subject

1853 1853 1853

006 July 5 July 9 George Rees Col. Surg. […] [re]questing information as to certifying to pay certificate of […] about […]

007 “ “ “ “ […] requisition […]

008 May 12 “ “ E.S. Curling and other Settlers […] a wish that the District may be named after Lord Clive

009 July 11 “ 11 Patrick Campbell […]

010 March 31 “ “ The Colonial Secretary Auckland […] Return of Appointment, VC to 31 March 1857[?]

011 July 9 “ 12 F.D. Bell Commt. […]

012 “ “ “ “ Henry T. Hill […] [..]pecting list of classes sent in by the Returning Officer of the Whanganui & Rangitikei Dist

013 “ 12 “ “ The Colonial Surgeon [su]pply of boots […] request fr. Their Patients in the Hospital

Entry in old register of 1853, now in National Archives, referring to the request of E.S. Curling and others that the district might be called after Lord Clive.

Page 8

an extensive search by some of the staff, who went to a considerable amount of trouble in the matter, a map was found at the Lands and Survey Department in Wellington which is apparently one of the copies made of Domett’s map. A photostat copy of this is now in the Hawke’s Bay Museum.

In his map we can see how much Napier owes to Alfred Domett. Here are the familiar names of the first streets – Emerson, Carlyle, Dickens and Thackeray, Tennyson, Browning and Byron, and the roads over the hill named after England’s greatest poets, Shakespeare, Milton and Chaucer. Here are shown the reserves set aside for Cemetery and Botanical Gardens. Here is Clive Square, and here we have Hastings Street, and also other streets named after men whose connection with India is now forgotten – Hardinge Road, Coote Road, Wellesley Road and Sale Street. The Western Spit is called Meeanee Spit, with Meeanee Quay on its inner side. Meeanee Spit is now Westshore, but Meeanee Quay is still there.

Alfred Domett held office for less than three years. The people of Nelson wanted him to represent them in Parliament, and he left Napier towards the end of 1856. Although he had called the port town after Sir Charles Napier, the name of Clive was not forgotten, and a township with this name was laid out, not at Pakowhai, as Domett had first thought, but at the mouth of the Ngaruroro River. Having the names of Napier and Clive on the map suggested the re-naming of the rivers, and for a time the Tutaekuri was called the “Meeanee” after Napier’s victory, and the Ngaruroro was called the “Plassey” after Lord Clive’s victory in India. In the first issues of the Hawke’s Bay Herald, which began publication in September, 1857, there are advertisements telling of properties for sale “in the township of Clive” and “on the bank of the Meeanee River”. For some reason or other the rivers reverted to their Maori names, but the Catholic mission on the Meeanee River became known as the Meeanee Mission, and so the district round it is still called Meeanee.

Now let us get back to the first letter of Domett’s to Dr. Featherston, with its reference to a “memorial” from the settlers. If that memorial was only in existence, with all its signatures, what an interesting bit of history it would be! Unfortunately, in this case, National Archives could only report that in an old register the memorial was noted as missing, but the entry showed that it was dated May 12, 1853, and that it was from settlers in Ahuriri asking that the district might be called “Clive” and that

Page 9

it was signed by “E. S. Curling and others.” This was some help, but it didn’t solve the question “Why Clive”. Why did settlers in New Zealand want to call their new home after a soldier and administrator famous in India?

There was another Curling here in the early days – John Curling – and when Miss A. M. Andersen was compiling the centennial booklet “Picture of a Province” she found a reference to him in Domett’s letter-book which showed he had been in India. Domett had been asked to suggest names of men who might serve as Justice of the Peace, and in a letter dated February 28, 1856, he gives the names of Capt. J. C. L. Carter, John Curling, Donald Gollan, Alfred Newman and James Anderson. Of John Curling he says:

“Mr Curling was employed for some years in a situation of great responsibility by Sir C. Napier in Scinde at the court of the Scindian rajah.”

And there was another man who had been in India, and that was Capt. Joseph Thomas, one of the surveyors employed by Donald McLean. Mr I. L. Mills, who has made a careful study of McLean’s diaries, has found mention there of both Capt. Thomas and of a “Curling” who is almost certainly John Curling, though no initial is given. Capt. Thomas had served in the army in India, leaving there in the early 1830’s, and had done survey work in other parts of New Zealand, particularly in Canterbury, before coming to Ahuriri.

It seems likely that from one, or both, of these men must have come the suggestion to call the new settlement after Lord Clive, and so a memorial was sent to the Governor asking that this might be done.

These “Indian” names have roused the curiosity of many people, and because so much material relating to the early history of Napier is stowed away in National Archives, and is not readily available, a legend has grown up that these names were bestowed by the regiments stationed in Napier for a few years, particularly by the 65th Regiment, which was the first to come. Because of trouble between two local chiefs the settlers had asked for military protection, so a detachment of the 65th was sent down from Auckland and arrived at Napier in February, 1858.

They did not bring any Indian names with them. As we have seen, names like Napier and Clive, Meeanee and Scinde Island, were in use before ever the regiment came

Page 11

here. Moreover, the 65th had been in New Zealand for twelve years before coming to Napier. A detachment of this regiment arrived at Wellington in July, 1846, sent there because of trouble with the Maoris in the Hutt Valley and elsewhere. Certainly, like most British regiments, the 65th had seen service in India, but had left there in 1822, quite a long time before coming to this country.

The only place-name the 65th might have had anything to do with is Havelock. The first sale of sections took place in January 1860, so the surveying must have been going on through the previous year – the first year of the Hawke’s Bay Provincial Government – and may have started earlier. The Indian Mutiny happened in 1857. In October of that year Sir Henry Havelock relieved the English garrison at Lucknow, and before the end of the year he had died from sickness. All through 1858, and probably 1859, accounts of the Mutiny would be appearing in the English papers and would be copied into the New Zealand papers when the English mail arrived. These accounts would be read with interest by the officers of the garrison at Napier, and it may be that someone connected with the 65th suggested the name of Havelock for the new township which was being surveyed. Or the Provincial Government might have thought of it for themselves.

Whatever the reason, the Provincial Government certainly became very “Mutiny-minded” about this time, because an old map of Napier dated 1861, shows new streets with names like Havelock Road and Delhi Road, which must have been named a year or two before that. Hyderabad Road, which is marked on Domett’s map, but not named, is named on this map of 1861.

As for the town of Hastings, it certainly had nothing to do with the regiments, which had all departed before it was even thought of. All British troops had been withdrawn from this country before 1870. The first sale of sections in Hastings took place in 1873. A few years before that Francis Hicks had first leased and then bought the land from Thomas Tanner with the intention of laying out a town. According to J. G. Wilson’s “History of Hawke’s Bay”, in the Deed of Sale the intended town was called “Hicksville”, but the name was soon changed to Hastings presumably to match the other Indian names. Warren Hastings was the first Governor-General of the East Indi Company. His trial for corruption while in office was one of the sensations of the late eighteenth century in England. The trial lasted seven years, and though he was acquitted

Page 12

in the end, the expenses of his defence cost him most of his fortune, and he would have been reduced to poverty if the East India Company had not granted him a pension.

NOTES TO THE NAMING OF NAPIER

The first white woman in Hawke’s Bay was Elizabeth Colenso, wife of William Colenso, the missionary. With her husband and small daughter she came through the surf near Waitangi in a small boat at half-past eight in the evening on December 30, 1844. The second white woman was Mrs Jane Hamlin whose husband was appointed to the Mission Station at Wairoa. The Colensos and the Hamlins left Auckland in December, 1844, for their stations on the East Coast in a small ship called the Nimrod. On December 24, Christmas Eve, the Nimrod put into Turanga (Gisborne) where there was a Mission station under the control of William Williams. There the Hamlin family disembarked, but the Colenso family continued to Ahuriri. Mrs Hamlin and the children stayed at the Mission Station, while Mr Hamlin went on to Wairoa to see about getting a house built. Early in February he went up to Turanga to get his family, and with parties of Maoris helping to carry the baggage and the children, they walked to Wairoa, arriving there on February 15, 1845. The date that the family left Turanga is given in William Williams’ diaries, which are in the Turnbull Library.

The next women were Sarah McKain, wife of James McKain, and Robina Villers wife of William Villers. The two families came up from Wellington in the schooner Salopian in December 1850, and we have no means of knowing which of the women stepped ashore first at Ahuriri.

The first white child born in Napier was Mary Jane Villers, born at what is now Westshore on November 19, 1851. She was the daughter of William and Robina Villers.

The device of the three conventional roses on the cover is taken from the arms of the City of Napier. These roses are also part of the arms of the Napier family, who gave permission for them to be used by the City.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.