- Home

- Collections

- COLLETT MA

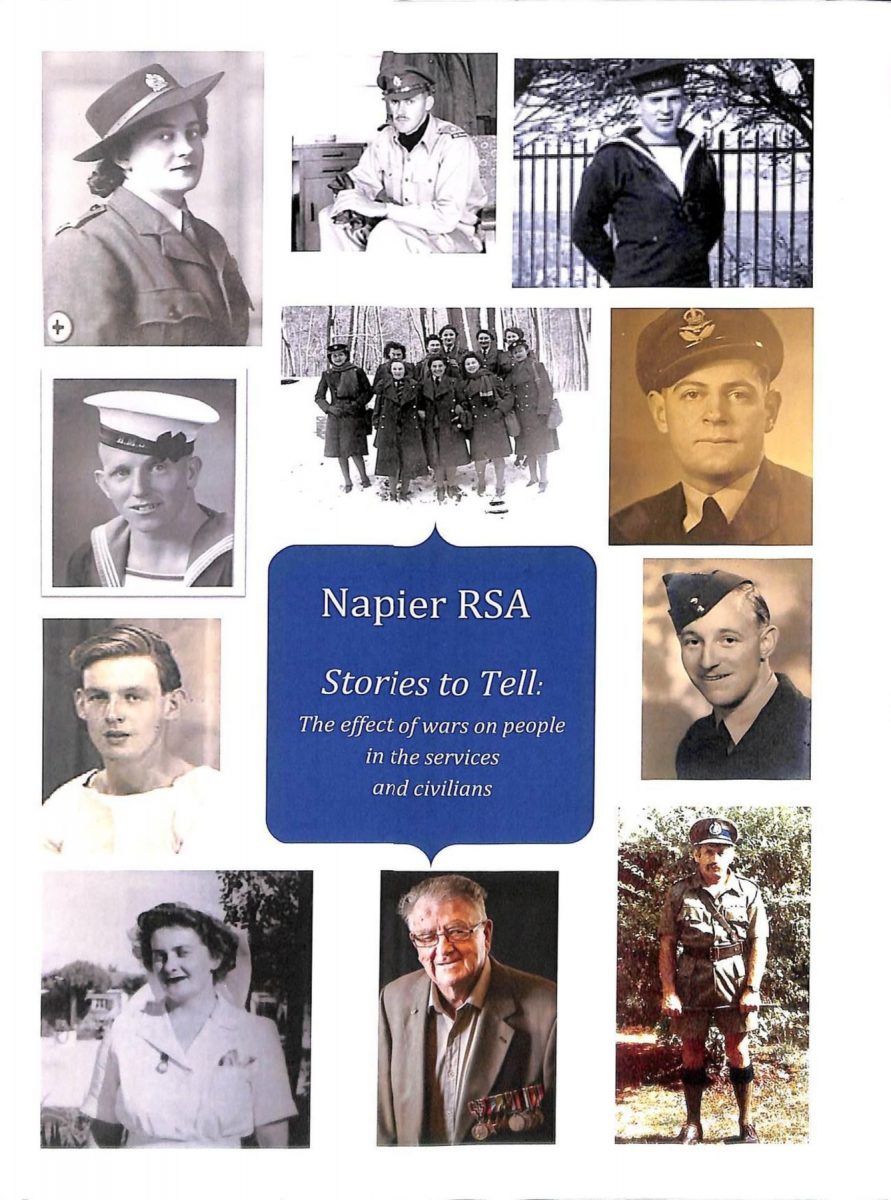

- Napier RSA - Stories to Tell

Napier RSA – Stories to Tell

Page 2

To those involved

This publication is what comes from that which can be best described as a fledging of ideas amongst a few people who have shown perseverance, comradeship and courage over almost 12 months of weekly meetings and engagements with our Veterans across a broad base of conflicts.

Literacy Aotearoa and the many volunteers from the Napier & Taradale RSA who have spent an untold, un-tabulated number of hours, interviewing, compiling and composing the following stories.

They, like the people they write about have shared in an intimacy that is rarely, if ever experienced by others and will never be forgotten.

To all the Veterans, Volunteers & Support People who have given their all to ensure living history, the good, bad, funny and not so funny is never lost by the passing of a much loved family member.

Albeit trite, I sincerely ‘thank you’ all on behalf of the Napier Returned and Services Association

John Purcell Q.SM J. P.

First printing March 2015

Page 3

About this project

During 2013, Christopher Finlayson, as Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, announced the launch of WW100, a project to commemorate the centenary of New Zealand’s four-year involvement in World War 1. Promotional meetings were then held around the country.

Committee members from both the Napier Returned Service Association Inc. (RSA) and Literacy Aotearoa Hawke’s Bay attended one of these meetings. Afterwards, they discussed collaborating in an effort to gather stories from the public to relate people’s true-life experiences of war. The Taradale & District RSA also joined the project while the guidelines were still being worked out.

After the outbreak of World War 1, author H G Wells wrote an article for the London newspapers titled The War That Will End War. Wells later used the phrase, “the war to end war”, which was widely quoted, and commonly believed. Sadly, that hope was not realised, and WW1 was not to be mankind’s final war. The cautionary lessons which should have been taught by this devastating event weren’t learned.

Over the last century, there have been countless hostilities, from localized uprisings and rebellions to another all-out global conflict. Even to this day, populations continue to wage new wars. We persist in inflicting loss, pain and suffering on one another.

We salute the courage and sacrifice of all those currently involved in these attempts to improve their world and conquer tyranny. We believe that these inspiring personal stories need to be preserved. For the sake of future generations, people need to know about the past to find better ways of improving the future.

The story gathering process

It began with weekly sessions at the Napier RSA, held to orient the new participants. Would-be storytellers attended to learn writing skills, if they didn’t already know how to craft their work. There were also some who wanted to share, but were unable to do the actual writing and they worked with our literacy volunteers. And the wonderful volunteers learned new skills such as interview techniques, and brushed up on any rusty points of grammar and punctuation.

Sometimes, we backed up faulty memory and sketchy narrative with a bit of research. For the most part, we have written down each story exactly as the teller remembered it. While we strive to present an accurate account, the occasional error is inevitable, largely due to the length of time which has elapsed since many of the experiences included here. All particulars are as accurate as possible, but some finer details (e.g. a date) may be slightly out. Some tales were collected from the journals of the departed, so were left unedited.

Page 4

Table of Contents

Page 5 A Charmed Life John Dallin Dunlop, Q.S.M

Page 7 A Full Hand Stanley Robert Douglas

Page 12 A Spitfire Fighter Pilot Max Collett

Pages 15 An Artist In Wartime William Guy Harding

Pages 16 Balloons of a Different Kind Ruby Cook nee Ruby Bull

Pages 19 Blow Out George Rogers

Page 20 From Millinery to Military Thea Lister

Page 21 In Uniform Author Unknown

Page 22 Military Exploits of the Natusch Family Guy Natusch

Pages 26 Morse and Motors Eileen Mogridge, nee Faulknor

Page 28 My Earliest Recollections of the War Eric Rogers

Page 29 My Family, Air Raids and Bomb Shelters Christine Hough

Page 31 My Korean Experience 2nd Lt. Colin Herbert Stansfield

Page 34 My Lucky Dancing Shoes Bill Walker

Page 36 Packing Food Parcels Judy Rogers

Page 37 Perils of the Merchant Navy Richard James Blundell

Page 40 Recipes for Food Parcels Arthur Hughes

Page 41 Royal NZ Navy Radar, Right Royal Leave Johnny Barham

Page 45 Sergeant Gregory George Chapman Excerpts from his 1916 Diary

Page 47 Service in British South Africa Robert Gillett

Page 50 The Black Coat In the Closet Marjorie Katherine Moore

Page 54 The End of the Road Ian John (Scotty) Burton

Page 57 The Malayan Emergency of the 1950’s Peter Gibsone

Page 58 Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd Angela Harford

Page 59 War Bride in Bomber Command Joy Thornton nee Pilkington

Page 5

A Charmed Life

John Dallin Dunlop, Q.S.M.

RNZAF and RAF NZ4214088

I was always interested in astronomy. My knowledge of the stars, along with good math skills, served me well when I joined the air force.

Some of my early training was done in Canada, before I was sent to Stranraer in Scotland in June 1944. Here we worked on familiarisation flight training. From November 1943 until April 1944, I trained to be a navigator. On 7 April, 1944, I became a Qualified Air Navigator. Then I was stationed in England in May of 1944.

From 29 November 1944 until 23 April 1945, I served as a navigator with the RAF. By the beginning of December, I was part of the crew of a Lancaster bomber in Squadron 166, and flew with her during 29 operation sorties over Germany, clocking up 67 day and 188 night flying hours.

On these flights, one of our main targets was the city of Nuremberg, located in the very centre of Germany. It is the second-largest city in Bavaria, after Munich. Nuremberg held great significance during the Nazi Germany era. This city was a symbol of German pride, having in the past been the site of the Nazi party conventions. In addition, there were major industries In the Nuremberg area.

Because of the city’s relevance, its destruction would have an important psychological significance for the Allies. Air raids were intense. A number of raids took place from 29 August 1942 until 5 April 1945. In 1945, large-scale attacks were relentless. My squadron participated in a highly significant attack towards the end of this campaign, when on 2 January every 100 square meters was hit by 38 tons of bombs.

The following description of the bombing of Nurnberg is from the “Campaign Diary 1945” on the web site of the British Royal Air Force Bomber Command:

2/3 January 1945

Nuremberg: 514 Lancasters and 7 Mosquitos of Nos 1, 3, 6 and 8 groups. Four Lancasters were lost and 2 crashed in France. Nuremberg, scene of so many disappointments for Bomber Command, finally succumbed to this attack. The Pathfinders produced good ground-marking in conditions of clear visibility and with the help of a rising full moon. The centre of the city, particularly the eastern half, was destroyed. The castle, the Rathaus, almost all of the churches and about 2,000 preserved medieval houses went up in flames. The area of destruction also extended into the more modern north-eastern and southern city areas. The industrial area in the south, containing the important MAN and Siemens factories, and the railway areas were also severely damaged… It was a near-perfect example of area bombing.

[nemet_sorstragedia_en.lorincz-veger].hu

[http:]//www.scrapbookpages.com/Nurnberg/Nurnberg01.html

Page 6

There were more hazards to our flying than being taken out by enemy fire. With so many planes involved in the attacks, mid-air collisions were one of the biggest risks. Other dangers we faced included the risks of collapsing due to lack of oxygen, or of the plane icing over. Sometimes we had to break ice in the tube.

Aiming at your target is very challenging. While we flew at an altitude of 20,000 feet in most cases, we would have to go down to 8000 feet over a target, and whilst in Transport 78th Squadron, navigation was basic. It might take 20 minutes to get a fix on a target.

What with the physical exertion, the mental concentration and emotion, this was very tiring work. We hardly ever socialised with the other flying crews.

During these early sorties, while we were still an inexperienced crew, we were very lucky. Once I had a bit of flak come at me, but all in all, we had no problems.

After the war, I transferred to the Reserve of Officers on 9 July 1947, and was asked to stay on in the RNZAF when I returned to New Zealand.

Page 7

A Full Hand

Stanley Robert Douglas

This is Stan’s full hand of medals. There is a General Service medal as well as five stars, one for every finger in his hand. These were earned over the various campaigns in which he served during WWII.

The following story focuses mainly on events in the Arctic region, for which Stan earned the Arctic Star. Clearly, there are many other stories relating to the other awards.

Middlesbrough, where I grew up, is an industrial city. Before the war began, it was busy with iron works, and steelmills, building ships and making munitions. I remember the night bombings which began when I was sixteen years old, too young to enlist. In order to volunteer to join the navy, you had to be eighteen. There was nothing for it but to wait. We lived in Captain Cook’s country and our family had always been seafarers, so I knew it was the navy for me. Besides, I’d heard my older brother’s stories of his experiences in the Territorial Army. Nothing he had to say when he came home would have persuaded me to join another branch of the services.

I did not tell the family I had enlisted until the letter arrived with details for my departure. This was in May 1941, and I was 18 ½ years old. Although this was my first time away from home, I wasn’t frightened. I just wanted to get there.

Training was in Portsmouth. Black-outs were taking place every night, so it was dark on the night of my arrival. A Royal Navy truck collected twenty of us from the train station for the ride to the barracks. We were all young men, coming from all over the country, of different classes, and destined to go our separate ways after training for our different naval careers.

The city of Portsmouth was in chaos, and the barracks had been hit under a night bomber attack. We were each provided with a hammock to sling in the cycle shed, our home for the first week. Training there lasted three months, marching from Portsmouth Barracks to the former Portsmouth Grammar School. All the children had

Photo caption – The 1939-45 Star, The Battle of the Atlantic ribbon with the France and Germany star, the Arctic Star (awarded belatedly in 2014). The Africa Star (1942) with clasp and The Pacific Star

Page 8

been sent away from the city for their own safety, and their school was set up as a ship for training purposes.

Here I learned everything I needed to work as a ship’s engineer. It was a quick apprenticeship, giving me everything except hands-on experience. You really have to learn your job at sea.

Then we had a pleasant surprise. We were drafted to Skegness, a former Billy Butlin’s holiday camp, renamed HMS Royal Arthur, class 125, where we were to finish our land-based training. Here we got away from old Portsmouth and her barracks for 1000 men; away from the night bombings and air raid sirens. The idea of holiday camps was quite new, and this specific camp had only started just before the war had begun. The facilities were new and spacious, and we had fitness training that included some very enjoyable activities such as boating and swimming.

The Mediterranean Front

My first ship was the HMS Bagshot, a minesweeper based in Alexandria. I was aboard her, and the HMS Speedy, in the Mediterranean in 1942 and 1943. After two years in the Med, participating in many naval operations, I finally got a chance to go home on leave, just a month after my twenty-first birthday.

I enjoyed the train trip home, although there were many devastating sights of destruction along the way. Due to the strict censorship of the day, there were no phone calls home to announce your pending arrival. You just turned up on the doorstep, day or night. The time went very quickly, spent in the normal manner, catching up with the locals, visiting cousins and eating in pubs. On Sundays, we still had a roast with Yorkshire pudding and veggies, thanks to Dad’s allotment. To be able to sleep in a bed once again was heaven; I said my prayers and thanked God that, so far, I had survived.

But, now my time at home was up. The war ruled all of our lives as I left for Portsmouth once again.

The HMS Javelin

My next draft from Portsmouth was to the J Class Destroyer HMS Javelin. She was new compared to the Bagshot. I went aboard the Javelin in November, 1943. She had everything; the speed, the firepower and a fine wartime record. At the age of twenty-one, it was all I desired.

I spent four weeks as a member of a working party, getting to know the ship and my new team. We had to test every aspect of the ship to assure all was in working order, and that we knew how to operate everything. After these working-up trials,

Page 9

Javelin set sail in December, joining the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow. We had no Christmas celebrations at sea. In fact, the last time I’d enjoyed a proper family Christmas feast was in 1940, and it wasn’t until I was in Canberra in 1945 that I had the chance to eat another Christmas dinner.

Scapa Flow

Throughout January of 1944 we continued with sea trials aboard the Javelin at Scapa Flow, north of Scotland. It was very isolated. There was no mail, just a desolate naval base. The only reasons to go ashore were to stretch your legs or go to the ‘wet canteen’, so called because to get to it, you had to wear your oilskins. There was nothing else to do there on Stornaway Island.

Up here in the North Sea, we had to contend with the elements. The most challenging aspect of life aboard became simply coping with the weather. We encountered fierce winds, strong currents and high seas. The seas were so rough that the big waves would easily knock you down. I still suffer with crook knees as a consequence of the rough treatment we got from nature.

While we were stationed in Scapa Flow, we frequently went on patrol. When you are on patrol, each ship is independent, free to come and go, without the backing and support of other craft. The reason behind this arduous task of patrolling the sea off Norway and Iceland was the German Battleship Tirpitz. Anchored in the Norwegian port of Narvik, it remained a constant threat to the shipping lanes to the Atlantic. This priority was not an easy task to achieve, but it was necessary. Because of all this Allied activity. Hitler thought we would land in Norway. Consequently he diverted troops from Russia, making that front vulnerable.

We would leave for a patrol, which lasted about twelve days at a time; our endurance was tested to the limit. The most urgent need was to refuel etc. This brought the crew a welcome respite.

Russian convoys

From Scapa, we also did Convoy work, working in a coordinated movement, to protect vital shipping. There would be thirty of our destroyers escorting the Aircraft Carriers 3000 nautical miles to Russia through northern waters, including the Arctic. Our escort duty was to act as an outer defence, using our own initiative to move and protect other ships in the convoy. We did this by screening for any approaching U-boats and enemy planes.

Photo caption – [http:]//www.naval-history.net/Photo10ddJavelin1DFeatherS.JPG>

Page 10

Operation Tungsten

At the end of April we formed part of the covering force for the fleet in Operation Tungsten.

On the second attack by the Fleet Air Arm, the Javelin was in a position to retrieve any downed pilots. This mission brought us into the Land of the Midnight Sun – a most rewarding experience.

While escorting the aircraft carriers, we had to sail at the outer limit of the German pilots’ flying range. This extra travelling distance caused us to risk fuel shortages. One day in early May, Javelin ran out of fuel and found herself left stationary in the Arctic Circle. We were stalled there for three days, which proved to be a nice quiet time. We actually enjoyed the break, knowing we were safe for that time because here, Javelin was far away from the action.

I woke up one morning to find snow on deck. The ship, covered in a mantle of snow, looked dramatic and dangerous.

Operation Veritas

During Operation Veritas, the Home Fleet’s Air Arm conducted reconnaissance flights off Narvik, Norway to verify that the Tirpitz was no longer a threat to the planned invasion of Europe.

The disabling of the Tirpitz was accomplished by the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, and four CAMS (carrier armed merchant ships, which had been converted for the war effort). The result of this encounter was that Tirpitz was prevented from participating on D-Day. If she had still been active, the outcome of that operation might have been quite different.

On our return to Scapa, King George VI paid a visit to the Home Fleet. This was a rare occasion, but the buzz on the mess deck was that we had been earmarked for the upcoming allied invasion of Europe, ‘OPERATION OVERLORD’. This designation would be replaced by the more common, D-Day, Tuesday, 6 June 1944.

Operation Neptune

In May the Javelin joined the 10th Destroyer Flotilla, Plymouth Command, for patrol and covering duties connected with Operation Neptune – the planned landings in Normandy. The main task of the 10th Flotilla was to protect the western flank of the invasion force from attacks by the German Navy. We numbered eight ships, being four British, two Canadian and two Polish destroyers.

By 6 June, we were off Alderney which was in occupied France, headed toward Normandy. There, pillboxes lined the cliffs; we looked for visuals from the enemy fire and trained our guns to take them out.

Early in the morning of 9 June, the flotilla intercepted three German destroyers and one torpedo boat of the German 8th Defence Force, which were being sent from Brest

Page 11

to Cherbourg, with the objective of striking at the heart of the Allied supply lines across the Channel. First we sank one destroyer, then another. The third German casualty was driven aground on the Isle de Bas where she was wrecked. Only the fourth ship escaped to go back to Brest, but had sustained damage which kept her out of action until July. These actions saved the whole operation, as this was the first and last attempt by German destroyers to interrupt the invasion.

We carried on fighting until 2 July, when we had a collision with the HMS Eskimo which was out of control. She hit the Javelin amidships. After a few hours were spent assessing the damage and exploring possible ways to safely disengage the ships, we attempted to separate them by cautiously easing the Eskimo toward the stern of the Javelin. Unfortunately, during the manoeuvre, some of our ammunition exploded in the hold, blowing the bow off of the Eskimo. The two ships were both badly damaged but able to return to Plymouth; the Javelin continued under her own power, but the Eskimo had to be towed back to England. Casualties on board the Javelin were three men killed and one injured.

With Javelin out of commission from 24 July until 31 December 1944, the crew members were all reassigned to other ships and other duties.

Meanwhile, the war had moved on. Victory at El-Alemein [Alamein] had brought the army to Italy. The Battle of the Atlantic was turning in our favour. Our next enemy, Japan, seemed to be the obvious new target. As the fleet was assembled, rumours became fact.

At Malta, I joined MHS [HMS] Camperdown, a modern Battle Class Destroyer and she transported me to my next adventure.

Never again

Never again a dawn will see

Those ships that day at Normandy.

They have sailed into history

With all our dreams and memories.

Page 12

A Spitfire Fighter Pilot

Max Collett

Waiting until he was 21 years of age to enlist with the army was not easy for a young dynamic Max

Collett. He enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force on his 18th birthday, and actually joined up on 1st April 1942. He’d followed his brothers, both already in the RNZAF. Their father (a great military man, a lieutenant in the Boer War and a captain in World War 1) was badly wounded at Passchendaele. Service to one’s King and Country was held high in the Collett household.

Max’s training began in New Zealand in Tiger Moth aircraft, in which he completed 82 hours before leaving for further training in Canada. Here Max was introduced to the Harvard and Yale aircraft in which he undertook 149 hours of training.

Following the training in Canada, he was shipped to the UK where his training continued flying the Miles Masters aircraft. From here he was posted to OTU (Operational Training Unit), and then to the revered Spitfire aircraft. Then he was posted to 485 (NZ) Spitfire Squadron, which was then at rest at Drem, Scotland, after a very hectic time in Eleven Group in South England.

Operational flying began from Hornchurch, escorting medium bombers over France. Then his squadron became the first Spitfire squadron to become a dive-bombing squadron. Here, there was either a 500-pound bomb under the belly of the aircraft or two 250-pound bombs, one under each wing.

The squadron then became part of the tactical air force in preparation for the invasion of Europe. Max missed the actual D-Day operation, having broken his ankle two days before the invasion, but re-joined the squadron in time for the move to France.

The NZ 485 Squadron landed in France, at Carpiquet Airfield in Normandy, on 26th August, 1944, as part of 145 Wing, attached to and giving close support to the Canadian Army. By this stage the Luftwaffe had been defeated, and 485 Squadron spent the rest of the war bombing and strafing at the Army’s request.

On 20th September, Max received his own aircraft, naming her ‘Waipawa Special’ after his hometown in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. On the fuselage were the letters OUD, being that aircraft’s registration.

The Canadian Army would capture an airfield, to which his squadron would fly, and then operate from that field. In some cases, when a large area was captured, Anderson netting was laid out to form a runway, and that would become their interim base.

During their 18 months in France and Holland, the squadron slept and lived mainly in tents – three men to a tent.

Page 13

In Max’s time on the squadron he was involved with 36 dive bombing missions, and many, many, strafing occasions. Several of these strafing sorties were on different sized ‘bowser’ trucks carrying petrol and other fuels, both at airfields and in convoys. Known as ‘flamers’, they made a very memorable sight, Max recalled. As part of the strafing they also successfully knocked out aircraft on the ground at the German airfields.

On other occasions the 485 Spitfires would seek out vehicle convoys, from small to large. His logbook shows a number of sorties where the staff cars of the German army, lorries and other vehicles were knocked out.

One morning, with the heavy fog seemingly as close to the ground as it could get, F/O’s (Flying Officers) Terry Kearins and Max were scrambled, literally just metres above the sea in heavy fog. Their two Spitfires completely surprised three midget submarines on the surface outside Flushing Harbour, Holland. They attacked, and sunk all three. While these were designated ‘midget’ submarines they were in effect fairly large, as was to be seen at the close of the war when this type of submarine was viewed by allied officers.

To the best of Max’s belief, this is the only recorded occasion of a Spitfire of the RAF or RNZAF sinking a submarine in the whole of the war. He was also involved in dive-bombing bridges over the river Rhine. On one of these occasions Max was hit by anti-aircraft fire and had to bail out. Fortunately being over allies lines, he was not captured.

At Bodenplatte on 1st January 1945, Hitler made one last attempt to drive the allies out of Europe. The Army attacked through the Ardennes and the Luftwaffe attacked many airfields in use by the allies. Six ME109’s attacked the airfield of 485 (NZ) Squadron. Thirteen Spitfires were lost. During this period, Hitler’s air force lost over 200 pilots, whom he could not afford to lose.

The squadron was to be converted to Tempests, so Max and the squadron went back to England to undertake a conversion course. But because of heavy losses due to mechanical problems and losses from anti-aircraft fire, there were not enough Tempests to equip the squadron. So they went back to Spitfires with a Packard Merlin engine. The Mk9b they had was the most advanced Spitfire of that time.

Some months were spent as part of the occupational forces in Germany, where the squadron would fly most days in wingtip-to-wingtip formations, indicating to the German people that they were there in a resolute way.

During some of the time in Germany, they were quartered in former Luftwaffe mess. As Max was about to leave, while checking he had not left anything behind, he pulled a German Luftwaffe logbook from under the bed. He packed this and returned to New Zealand with it. About 40 years later, through the German Embassy, Max was able to trace the owner of the logbook (a navigator of JU88’s and ME110’s), and return it to him.

Max commented, “You can imagine the German person receiving his logbook from ‘some bloke’ in Waipawa in New Zealand.” They corresponded with each other through the sending of Christmas cards for some years. Sadly the card exchange came to an end about three years ago. It would seem that logbook’s owner has passed on.

Page 14

Max left Germany on the 6th May 1945. The 485 (NZ) Squadron was in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany, overseeing the end to World War 2.

Max was awarded an MID (mention in dispatches) before he left the squadron to come home. Three days before his 22nd birthday, on 22nd October 1945, he returned to New Zealand. He had been serving, well and truly, for three and a half years.

Postscript: Max is an RSA Gold Star recipient, almost immediately becoming a member of the RSA on his return from active service and serving as secretary to the Waipukurau RSA. In his professional role as an accountant, he also ‘did the books’ for Napier RSA for around 30 years.

Anecdote

Even in wartime amongst the horror and trying times that all endured, there were moments of humour and interest. Two such events, in which Max was involved, are shown below (taken from the Summons). Both are dated 30th October 1943.

Refer to ‘Summons’ at Alnwick in the county of Northumberland,’ to appear before the Court of Summary Jurisdiction. – Maxwell A Collett, Sergeant Pilot. How do you plead?

1 – Statement of offence: More than one person carried on a bicycle, contrary to Sec 20 of the Road Traffic Act 1934.

On a certain road called Bondgate Without, was one of two persons unlawfully carried on a bicycle not propelled by mechanical power and not adapted or constructed for the carriage of more than one person.

2 – Statement of offence: Bicycle not displaying lights, contrary to Road Transport lighting Act 1927 and Lighting (restrictions) order 1940 made under Defence (general) Regulations 1939.

Unlawfully during the hours of darkness to wit at 10.55pm did cause a bicycle to be on a certain road called Bondgate Without, which did not display the front light required by and under the Road Transport Lighting Act 1927 and a red rear light, contrary to the Lighting (Restrictions) order 1940. Paras. 31 and 52(4).

Outcome? 485 NZ Squadron moved back to frontline combat. Hence the case did not proceed.

Page 15

An Artist in Wartime

William Guy Harding

As told by his daughter, Judy Rogers

William Harding was originally from Auckland. He became a professional artist, both a portraitist and one of our country’s top draftsmen. When the Second World War broke out, he worked for New Zealand as a cartographer, drawing maps for the Lands and Surveys Department.

As he was already doing an important job, and because he had a family to support, it wasn’t until the last year of the war that he was called up to serve overseas.

While on the troop ship, William made some extra money by doing portraits of the servicemen with whom he sailed.

His daughter Judy inherited her father’s artistic talents. This is her portrait of her father, drawn in 1946.

Page 16

Balloons of a Different Kind

Ruby Cook nee Ruby Bull

Women’s Auxiliary Air Force – 2093791

Ruby lived in the East End of London with her mother, sister and brother-in-law. Her ambition was to become a qualified dressmaker and she duly obtained employment with a Jewish family firm. Ruby’s new adult world was looking promising, but her carefree days came to an end with the outbreak of WW2, and the subsequent bombing of London. Her employers were now required to have the staff sew uniforms for the forces.

Ruby’s mother was deaf. She could not hear the air-raid sirens when home alone, and did not realise the urgency to rush to an air raid shelter. The family decided to move to Leicester. The only employment available to Ruby after the shift was in a biscuit factory, a placement Ruby found somewhat tedious. Ruby, hoping to find other work, was dismayed when she found that she could not leave because work in food-producing establishments was considered to be essential employment.

It was then that Ruby made a life-changing decision. She enlisted in the WAAFs (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force). She was assigned to a Barrage Balloon Command, one of the many situated in strategic parts of the country. This occupation was earlier handled by officers and men of the Royal Air Force. It was suggested in the House of Commons that women could do this work which would release the men for heavier work. The men were appalled, being of the opinion only physically fit men were up to handling the balloons. An extract from The Star newspaper on 12 July 1941, follows this story.

What Was the Purpose of Barrage Balloons?

Many people thought their purpose was to ensnare aircraft in their metal cables, like a spider trapping unwary flies, but this was not so. However, if an enemy aircraft did become entangled, this was considered a bonus. Their main object was to deny enemy aircraft low level airspace forcing them to fly higher, and thus decreasing their bombing accuracy.

What Were Barrage Balloons?

The balloons, which averaged 62 feet in length and 25 feet in diameter, were made of a very close woven fabric which consisted of several panels. They could be likened to “blimps”. The top of the balloon was filled with hydrogen white the bottom was left empty. The balloons, which were capable of flying to 5000 feet, were held by cables fixed to winches on trucks.

Page 17

Ruby was very excited about returning to London, although a little apprehensive about her new venture. She shared a three-storied house, situated on the edge of the Commons, with ten to twelve other WAAFs. The roster for household duties was the least of her worries. But then came the training, engaging the WAAFs in the numerous so-called seemingly impossible tasks for the fairer sex. Ruby was quite determined. One of the first things to learn was how to drive a vehicle. She also had to become skilled at operating winches, and to familiarise herself with equipment and devices previously unknown to her. The repairing tasks were not so difficult.

When word came through that an attack was imminent, it was time to man the balloons. The trucks were driven to the desired spot and the women could commence their routines. The winch, which was like a steering wheel, was hard to manoeuvre. In fact in wet and windy conditions it was extremely hazardous.

Care was also needed when the balloons were brought down. They had to be lowered to a concrete base and anchored with very heavy concrete blocks. Then an inspection of the hydrogen level was taken and any damages noted. It took a real team effort to successfully launch and lower the balloons.

Ruby did find the manning of the balloons physically strenuous, but the satisfaction of a job well done was very rewarding. As Ruby would be the first to admit, “It was your job and you just got on with it”. This in turn enhanced the camaraderie between the WAAFs. Ruby felt so at home, she even planted tomatoes.

But not all the WAAFs were happy with their situation. Two women from the northern parts of England, referred to as “the comedians”, made it quite obvious they were disgruntled with their circumstances. So much so that they stated that when next on home leave, they would get pregnant. This they managed to do and were duly discharged.

Life was not all work and no play. Ruby was sometimes able to take a two-day home leave. As there was a library and a pub just down the road, there was plenty of scope for socialising; perhaps at the pub more so than the library.

The precious balloons had to be guarded throughout the night and the roster specified shifts of two hours on and four hours off. At first there was only one woman on duty but it was then decided two women would be a better arrangement. Could this be because there was an army training college further down the road and soldiers, including those from the Unites States, would be passing by? The women would often see them on training exercises and marching drills.

Page 18

One night when Ruby was dozing between her two hour rosters, she was a bit grumpy on being woken. She was told not to grizzle because “there is a smashing looking man out there”. Ruby did find him smashing, and so began a friendship, a courtship and then an engagement. Ted Cook was sent abroad and did not return until the end of the war, when they married.

At the end of the war, Ruby was demobbed and worked in an office while waiting for her husband’s return. He was assigned to further duties in Italy. After hearing glowing reports of Napier, from the woman in the adjoining flat, they decided to immigrate to New Zealand.

An article from The Star – Monday 12, 1941

BALLOON JOB TOO STRENUOUS FOR WOMEN

By our Air Correspondent

Men employed in the air barrage are disturbed by stories that women are to take over their jobs. The allegation is not true because the work is too strenuous for women. This very fact has caused the Barrage Balloon boys much embarrassment as there is a feeling on board that the work they are doing could be done by girls. The trouble arose over questions asked in the House of Commons last week suggesting that women could do the work and that officers and men engaged on it would be released for more important and heavier work.

A MISTAKE

In reply to the question it was stated that the intention of the RAF was to employ many WAAFs as possible in balloon command. Many WAAFs are already employed, and ways and means of extending their employment is now being considered. It is a mistake however to assume this means women will “man” the balloons That would not be possible.

HEAVY WORK

Most of the balloons of these sites are in exposed places, living conditions are very rough and to handle a balloon in a breeze is heavy work even for a physically fit man. An unfit man would be entirely incapable of doing the work. It is definitely a man’s job and the men engaged on it have no reason to be self-conscious about their task. The women who will be employed will be employed on electric duties, repairing balloon fabric and such similar work.

Images used in this article:

360 X 240 retronaut.[com] – balloon/trucks in hanger

780 X 520 the times.co.[uk] – mending the balloon

1280 X 960 pinterest.[com] – pulling down balloon

Page 19

Blow out

George Rogers

When Winston Churchill declared that his country would enter into the War, George Rogers promptly volunteered to serve.

Then, while he was waiting to be posted, one night his bedroom wall was blown out by a bomb and he was thrown outside, still in bed. Luckily, though there was plenty of damage done to the building, not much harm came to George.

Most young men longed to fill the glamour positions, to become generals and flying aces. When he enlisted, George had aspirations to be a fighter pilot. But high-flying glory was not on the cards for George.

George was a plumber by trade, and had also worked underground on the tube trains. So when he was asked what he knew about Lancaster bombers, being such a practical hands-on man, George replied, “I can take them to bits and put them back together again”. This skill was far too valuable for the Air Force to allow him to fly; George was needed on the ground to keep the precious bombers air-worthy. And so it was that George worked on the planes flown by the now-famous Dam Busters.

They say that lightning never strikes twice. Obviously the same adage doesn’t apply to enemy bombs. George’s next personal encounter with one was when he was a Flight Sergeant. One night an injured plane returned through thick fog from a mission. She landed with her tail on fire, and George saw that there was still a bomb under her wing. He ordered his men to get that bomb off, but it blew up before they could remove it. He was thrown, and his ears bled from the percussion. George simply stuffed some cotton wool into his ears and carried on, but from that day on, his hearing has been affected.

Eventually George came to New Zealand as a plumber on a warship. He liked what he saw, and decided to stay.

Page 20

From Millinery to Military

Thea Lister

Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps

As told by her cousin, Jenny Vierkotten

When Thea left school, she worked at the Harris Hats factory in Napier.

Along with her extended family, and many other Napier citizens, she gathered at “Siberia” to wave goodbye to the troop train that was carrying an older cousin as he left for war. Siberia was the colloquial name for a small grass reserve near McGrath Street. Only immediate families of the departing soldiers were permitted on the railway platform.

It was then that Thea felt moved to contribute to the war effort and joined the WAACs (Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps). This meant a move to Wellington where she was stationed at Trentham Military Camp throughout her service.

After initial training, Thea was assigned to the Quartermaster’s Store. The WAACs worked in pairs receiving and preparing artillery for either storage or reissue to different units. They also serviced the Bofors guns while soldiers looked after the 3.7 inch guns, this latter work deemed too heavy for the WAACs. Both these were anti-aircraft guns.

Whenever the WAACs were able to obtain a leave pass, they would go by train to Wellington for some social activity, mostly attending the cinema or the Saturday night dance.

On waking one morning, Thea noticed a rash and after reporting to the medical centre was questioned, most thoroughly, by the Matron. Matron’s first reaction was to ask, “Have you been out with any Americans?” Because the Americans, after being on combat duty in the Pacific, were now on Rest and Recreation leave in Wellington, Matron feared they may have brought small-pox or some other tropical disease into the country.

Thea emphatically replied that no, she had not been in contact with any Americans, and besides she had a boyfriend, Roy, serving in Europe. Thea was ordered to return to Napier where she recuperated from a common, although unpleasant, bout of chicken pox!

At the end of the war Thea married Roy Lister. Because of the coincidence of the surname she did not have a name-change. Although the couple lived in various places In the North Island, the bond between the WAACs was always strong even if they had served in different companies. This was confirmed by the number who attended Thea’s funeral so many years later.

Page 21

In Uniform

Author Unknown

Ngaire Rowe found the following poem in the personal effects of her late step-father. It is possible that he wrote it, but she can’t be sure.

In Uniform

Summer after winter

And hope that follows fear

Sunshine after shadow

And some time you’ll be here

Laughter after sorrow

And blossoms after frost

Joy and compensation

For all the months we lost.

Page 22

Military Exploits of the Natusch Family

Guy Natusch

DSC RNZNVR (Rtd)

MNZM for services to Architecture

Guy’s family served with distinction in the First World War, and this patriotism followed into the Second World War with both Guy and his brother Roy serving with the same Natusch excellence. Roy has an unbelievable, yet wonderfully courageous series of true tales to tell of his exploits for which he received the Military Medal.

The commitment of Guy, his brother and before that, his family, can best be summed up in a comment made by Guy at the time of providing the Oral History (referred to below) when he said; “You felt in your youth that what Germany was doing was wrong and that what we were going to have to do, very simply, had to be done. So I think it is as simple as that.”

The first short story is as he told it to Ron Rowe.

How I came to join the Navy against the wishes of the Army

It began in the army in December 1941, after a year at university in Auckland where Guy was studying for his architectural degree.

His unit was the Hawke’s Bay Regiment guarding the Manawatu Gorge. However, he had earlier applied to the navy for scheme B, which was an officer selection programme. During his brief time with the army he received an invitation to attend the Naval Selection Board and physical medical inspection in Wellington within seven days.

As all good servicepersons do, Guy applied for leave, so as to attend the selection board. This was refused! The grounds given were that the army were losing too many of their personnel to navy and air force.

Guy felt then and still does, that this decision was wrong. What to do? Simple, really … he was going to accept the invitation and attend, no matter what.

Without the knowledge of the army, Guy left the camp the night before the Selection Panel. He did so by going out under the flap of the Bell tent, through the pine trees and down to a railway crossing with the road. He stood in the darkness waiting for the train that he knew went through about this time. As the train came abreast with the crossing he leapt out and boarded it. It seemed a sensible thing to do . . . even if he could not buy a ticket because the army would not grant him a ‘leave pass.’

To avoid being caught by the military personnel on the train; Guy made use of the toilet any time a Military Marshal came into sight. And so his journey from Woodville to Wellington took place. On arrival in the capital he leapt off the train and disappeared into the crowd.

Page 23

Appearing before the Navy Selection Board, Guy was horrified to see his family doctor at the head of the table. In his childhood, Guy had suffered somewhat severe asthma and a troubling tendon in his right foot that still gave him bother. The doctor asked him about these two possible difficulties to which Guy replied in a very candid, but courteous fashion that his tendon Issue would not be helped with long distance marches with the army and that his asthma would be greatly assisted by the sea air. It seemed that the doctor agreed.

Once clear of the selection panel, Guy returned to the army camp at Woodville in the same manner to that by which he had left it. On arrival he asked others if he had been discovered as missing. The army hadn’t missed him, primarily through the help of friends at the camp.

A few days later he received a letter from the navy stating that he had been successful for the scheme B commissioned officer programme and would leave NZ In ten days’ time, embarking on the Rimutaka. Obviously the army now needed to know about this and the CO summoned Guy to explain himself after having been denied permission to attend the selection panel. Guy’s reply was, ‘I’ve no Idea Sir, evidently they must have selected on the information to hand.’

Just before his 21st birthday at the end of January, he, along with twenty nine others, set sail for the UK. Candidates for Scheme B were required to be 21 years of age, prior to or during their training. They all joined the Navy as ordinary seamen for basic training with at least six months sea time before qualifying for officer training school.

That’s how Guy Natusch joined the navy – quite a story, but true. “It seemed a sensible thing to do” – for If he had not made the very real effort to attend the selection panel he would not have taken part In some interesting exploits during the war on Motor Torpedo and Motor Torpedo Gun Boats (the two small ships are different) nor earned the Distinguished Service Cross. But that is all for another story …

Two convoys that changed my life

Guy tells this story in his own words.

Joining the Navy as a Scheme B candidate – i.e. candidate for officer training, required a short period of land-based training before one could be drafted to a ship. I was one of six New Zealanders who were fortunate to crew on HMS Tartar, a fleet destroyer of the Tribal class. Tartar, of around 2000 tons with 200 personnel had the latest in technology at the outset of World War 2. It had a twin, quick firing 5-inch anti-aircraft gun in a turret mounting, along with other armaments.

Page 24

HMS Tartar and her sister ships of the Tribal class could do well over 30 knots and were used to great effect. Yet sadly several of Tartar’s sister ships suffered the ultimate fate of being sunk.

The first convoy that I and the other five New Zealanders on scheme B were involved with was when HMS Tartar was part of convoy Pedestal, to that wonderful and courageous island, Malta.

The convoy was escorted by two battleships, four aircraft carriers, seven cruisers, thirty two destroyers and a number of smaller craft; all this to protect fourteen merchant ships that had to manage 15 knots. A very slow speed when one considers the many submarines lurking in wait, but fast for a convoy.

This convoy, Pedestal, was a ‘must get through at all costs’ as Malta and the military, mainly RAF, would have been lost if the convoy failed to deliver critical supplies of aero fuels and other necessities.

And the costs were extraordinarily high. The enemy threw in all of their resources to stop what they knew would be the making, or the undoing, of the strategically placed island.

HMS Eagle, a middle- to large-sized aircraft carrier, was sunk by four torpedoes on the first day out. Eagle couldn’t fly off her aircraft quick enough to offer further cover. This sinking was followed by another aircraft carrier being badly damaged also. HMS Kenya, a larger cruiser had her bow blown off and HMS Nigeria, of the same class, had her rudders blown off through a torpedo ‘up the stern.’ A destroyer, HMS Foresight was crippled, so Tartar took her in tow during the battle; but eventually had to sink her as Tartar herself became the target.

Such was the carnage that only five of the merchantmen got through. One was a NZ ship, the Port Chalmers, and another was a petrol tanker, the Ohio, which came into harbour with her decks awash and with a destroyer lashed to either side in order to keep her afloat. Ohio was only able to travel at a mere two knots. Courage and fortitude? You bet!! This was said to be the convoy that saved Malta. It was between attacks that I said to my shipmates, “Let’s hope that this is the war to end wars.” One of my Kiwi shipmates, five years my senior replied to me, “Guy, you must study the history of mankind – man does not learn from past events.”

To put this significant event into perspective, it is said that Germany dominated the straits and Rommel’s Africa Corps was only losing a small percentage of supplies across the Mediterranean. Once Malta was saved they lost thirty percent of supplies which contributed largely to the defeat of the Afrika Corps.

Page 25

This was my first experience of sea time and experiences of what war was really like. As soon as we were able to be released, the Tartar sped at over thirty knots back to Gibraltar so as to escape the submarine threats. From Gib we went to Scapa Flow for a boiler-clean.

While at Scapa Flow Naval Base undergoing essential repairs and maintenance, sporting events were arranged including rugby and sailing. The six Kiwis all took part in the team for HMS Tartar against all the other destroyers, cruisers and battleships. Tartar won five out of six rugby matches and thanks to the Kiwis, Tartar was victorious in sailing as well. Recreation, including organised sporting events, was very important to help us forget the horrors of war and prepare us mentally for the next battle.

Then to the second precarious convoy that my fellow Kiwis and I were involved in: Leaving Scapa Flow, heading to Iceland to join convoy PQ18 was cold and rough. The convoy PQ17 (the one before ours) was a complete disaster. So again the convoy that we were part of, PQ18 was critical, but this time from a political point of view to pacify the Russians, who, desperately short of supplies, needed the convoys to succeed.

The composition of the convoy, too, was of course markedly different. This time there were about forty merchant ships with the attendant escorts of a smaller number than the Malta convoy. Pedestal. Yet the losses again were high with, from memory, something in the order of thirty to forty percent losses. Forever etched in my memory are the tankers and freighters being blown apart. The other terrible factor was our having to steam past the seamen in the water from the sunken or foundering ships, because submarines were waiting for any other ship to stop and pick up survivors and then they too would more than likely receive the deadly torpedoes. Nevertheless, if we could pick them up, we did, by stopping momentarily, literally scooping them up. We did what we could, hoping the slower small craft could reach others in time.

And so I was part of two momentous and important convoys which played a major role in the war effort and also gave me and my Kiwi mates the sea time, and experience we needed in order to move to King Alfred Barracks for our officer training. After that, I was commissioned as a Sub- Lieutenant.

Again, another story.

Acknowledgement is made to the Royal NZ Naval Museum for providing the Oral History of Guy Kingdon Natusch, from which the genesis of stories has been taken.

Page 26

Morse and Motors

Eileen Mogridge, nee Eileen Faulknor

Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, No 804702

Eileen Faulknor was brought up in Napier South, Napier. She was a member of the St. Augustine’s Church and joined the Brownies and later the Girl Guides. She had no idea that the Morse code and semaphore, which she had studiously studied, would eventually be put to good use. When her brother joined the navy, he left behind his prized car, which Eileen was instructed to take care of. She was delighted and jumped at the chance to get her driver’s licence, another useful accomplishment.

In 1940, German raiders (and later Japanese naval boats) were invading Pacific waters as far south as New Zealand. They had attacked and sunk various vessels. Blackouts were in force by April, and householders were warned against leaving doors open. Because of her knowledge of signals, Eileen joined the team at the Drill Hall and Bluff Hill look-out stations where they listened for signals from any boats that might be patrolling in the Bay.

By 1942, the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps was founded, and Eileen was ordered to report to headquarters at Mirimar [Miramar], Wellington. Because no uniforms were available, the women were initially issued with men’s attire. Eileen adapted well to army life, sharing a hut with three other women. Having both driver’s and heavy vehicle licences was a definite advantage as that enabled Eileen to leave base on various missions. Although a confident driver, she admits that driving in blackout conditions was quite scary.

It was not long before Eileen was promoted to the rank of Sergeant, with one benefit being that she shared a hut with only one other woman. When asked what it was like being a Sergeant, Eileen smiled and replied, “My word was law!”

Working in Signals was an exacting job. The women did shifts throughout the night, and any intercepted messages were reported to the co-ordinating office.

Because the work was so intense, firm friendships were established. Just for a bit of fun, when out socially, they would greet a soldier with verbal dots and dashes, such as –

dot,dot,dot,dot (H);

dot (E);

dot,dash,dot,dot (L);

dot,dash,dot,dot (L);

dash,dash,dash (O).

Page 27

When Eileen received a welcome weekend pass, she returned home on the midnight train. The luggage racks were made of a type of rope and looked a little like hammocks.

Most times Eileen was able to leave her luggage on the seat and climb onto one of these racks, managing to have a bit of a sleep before arriving in Napier in the early morning. Eileen preferred to wear trousers when she travelled, and remembers very clearly how distasteful this was to one of her aunts. When the war ended Eileen remained in Wellington for a little longer, as there was still work to complete. Finally, she returned to Napier and was reunited with her fiancé, George Mogridge, who had been stationed in the Pacific.

A.- B-… C-.-. D-.. E. F..-. G–. H…. I.. J.— K-.- L.-.. M– N-. O— P.–. Q–.- R.-. S… T- U..- V..- W.- X-..- Y-.– Z–..

1.—- 2..— 3…– 4….- 5….. 6-…. 7–… 8—.. 9—-. 0—–

Page 28

My Earliest Recollections of the War

Eric Rogers

As a child I grew up in a village called Cogan, near Penarth in Wales. Behind our house was a hill, and on the top of this was a recreational field. This was near the border of England and Wales.

I was nearly 11 years old when war was announced by Neville Chamberlain. We had a Cossar battery radio to which we listened. I remember being issued with an identity card (which I still have) and a gas mask.

My mother was also given a ration book. Mum asked me to go to the shop, and as we had a ration book I said we would not have to pay. I was so wrong.

My father was an ARP Warden (Air Raid Precautions) and he came home one day and said to go outside. The recreational field was lit up with incendiary bombs which had been dumped by the German planes because of ack-ack fire. The whole field looked as though it was on fire.

The German planes would fly over from France, over the Bristol Channel, and either the river Thames or Severn. Our village was under their flight path.

Another time, Mr. March, who was an ARP Warden, saw a parachute coming down on the recreational field. He rushed up and found it was a landmine, which exploded. He was injured and rushed to hospital. He was very lucky to survive.

I joined the Royal Air Force on the 12th February, 1947, at the age of 18. I was kitted out at Padgate in Lancashire and then went to Yatesbury in Wiltshire for basic training.

Then I was sent to Melksham, which was also in Wiltshire, to start my schooling for my trade, which was an instrument repairer. I worked on all sorts of things, but they found out I was good on instruments, so I was sent to St Athens where I was put on the bench repairing instruments.

In late 1948, I was due to be de-mobbed, but owing to the Berlin air drop, I could not do this. I went into the Reserve for two years, and was still in this when I emigrated. I came out to New Zealand, leaving in October 1954 on the Captain Cook, and arrived in Dunedin in November 1954.

Text on book cover –

“ON HIS MAJESTY’S SERVICE

OFFICIAL PAID

YOUR RATION BOOK

Issued to safeguard your food supply

Name

Address

NATIONAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

Date of Issue

If found, please return to

FOOD OFFICE.

Serial Number of Book

BL 796254

R.B.2 (Child).”

Page 29

My Family, Air Raids and Bomb Shelters

Christine Hough

We were prime targets for getting bombed because we lived at Elm Park, Hornchurch in Essex, one mile from a Spitfire Aerodrome.

We had gone to stay with Mum’s sister who lived in North London at Palmers Green, My uncle earned more money than Dad did and he and my aunt had no children, so they were not eligible for a free Air Raid Shelter. As a consequence, they did not have one of their own. Every night, we took food and drink, and bedding including our pillows to the Underground station. Then we slept on the platform with lots of others.

My favourite war-time memory is of sleeping on the platform of Wood Green Railway Station. At that time, I was 10 years old, and thought it was cool.

After four weeks, we went home as the bombing where we lived had not eventuated at that time.

Once home, we had to sleep in our air raid shelter, something I’d rather not ever have to do again. I saw that Mum was absolutely terrified. We could feel the bombs explode in the ground and the shock waves met us from about a mile away. What an awful feeling!

Then a big gun we used to call Big Bertha would come round the streets and fire at the German planes in the sky overhead. They used this mobile gun so that the Germans could not pin-point it and bomb it, like they could have done if it was in a stationary position. The noise was unbearable.

In the morning Dad and I got out of our air raid shelter; me to get ready for school and Dad to go to work in London. Business as usual!

Photo captions –

An example of a backyard air raid shelter<[https]://encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcSr1f_9vA7hgQ5RldDiJD1xFzbZMB8S-9Zy-cauLXWvu2-ZrbDcQw>

Sleeping at the station<[https:]//encrypted-tbn2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcSDUPppO4X0nplmiRgSinkqcZvYSEecicKPam313A8HyOYWcRtolQ>

Page 30

After the first night of the Blitz, Dad told me to look down the road, where you could see London on fire. We were twelve miles away. The sky was bright red with yellow and green flames coming from all the goods in the dockyards.

I will never forget that sight,

I will never forget that night.

Many, many people lost their homes.

Their places of work as well.

My Auntie Doll was killed in the Blitz on London in one of the biggest disasters of the Second World War. On 13 October 1940, German bombers attacked the city. One of the heaviest bombs they dropped hit a block of flats called Coronation Avenue. The bomb penetrated five floors of the flats above the basement shelter where 154 people sought shelter. Damage from the bombing included the bursting of the building’s water mains and gas pipes. This caused people to be drowned or be poisoned by the escaping gas.

It took nearly two weeks of digging to find the victims’ remains. In all, there were only 128 of these people whose bodies were later identified. Identification was not easy. Many identification cards and other papers had been ruined by the water. The rescue workers gathered what personal effects they could from the corpses. Some personal items had become embedded in the bodies.

Auntie Doll had said that she felt safe in the shelter although it was unpleasant to be amongst so many people. Ironically her house was relatively unscathed and still stands to this day.

Footnote:

Christine’s memories of her Auntie Doll, as printed here, are adapted from her article Killed in the Blitz which was published in the North West Kent Family History Society Journal, Vol. 6 No 4, January 1993.

Photo caption –

Coronation Avenue plaque

[http:]//assefs.londonremembers.com/images/big/49789.jpg?1319394792

Text on plaque –

“CORONATION AVENUE

IN MEMORY OF

over 160 people who died when a high explosive bomb fell on this building during the Blitz

on

13th October 1940”

Page 31

My Korean Experience

Excerpts from the memoirs of

Second Lieutenant Colin Herbert Stansfield

New Zealand Army – No 5608084

Overseas Services

08 April to 03 September 1953

29 December to 04 November 1954

It was in 1952 that I decided to answer the Government’s call for volunteers for the New Zealand Forces to be sent to Korea. I thought it would be an adventure, so decided to sign up. I was 20 years of age and entered the training camp at Waiouru.

The military training consisted of marching, general discipline, small arms training, unarmed combat and obstacle course tests, followed by Corps training where you are drafted into sections, artillery, transport, and supply to name a few.

After aptitude tests, I was selected for officer training but as I was not 21, this was deferred in the meantime. Because of my age, I was not eligible for an overseas posting until I had my parent’s written permission. My mother would not agree, so I waited until my 21st birthday and a few weeks later I left for South Korea.

Our flights took us first to Sydney, where we spent a few days at the Marrackville, Eastern Command Army Barracks.

Our Qantas DC6 flight took us via New Guinea, to Guam Island, an American air base, where we stayed overnight. The next stop was Hiro Base Camp, Japan, staying a few days to be fitted out with combat gear. Then it was on to Seoul in South Korea.

We were met by a convoy of vehicles, and travelled some 60 miles, over very dusty clay roads, to our camp, known as the 38th. I was handed a pick and shovel by Corporal Jim Canning and ordered to dig a trench for an air raid shelter. It was late into the night when we finished, but it was a good introduction to my new life. The next night entailed more digging.

My section was required to dig trenches up the valley, away from the camp, which would be a light machinegun post. The digging was easy. The following day when inspecting our work we found out why. There had been an old toilet on the hill, and the area was full of maggots.

Text on sign –

“71

THIS IS WHERE IT IS

38º

NORTH LATITUDE

COURTESY 56 CDN TPT COY”

Page 32

Climatic conditions in South Korea presented a challenge. In summer months the heat was very uncomfortable, and the troops had to rest for two to three hours in the middle of the day. Salt tablets as well as Paludrine tablets for malaria were supplied.

Then along came the wet season with spectacular lightning displays and thunder storms.

Deep trenches around the tents had to be dug. More digging!

Winter brought snow, and everything froze. The clothing issued to the troops for the cold climate was good, so that coupled with our young age, meant we found the cold not too difficult. Woollen long-john underpants, string singlet, woollen ski trousers, woollen shirt, dark green nylon over-trousers and jacket, and then a fur lined parka, with hood, made up the winter clothing. Heavy socks and commando boots kept the feet warm. To keep cosy when sleeping, we wore either our first layer of clothes or even the first and second, inside two sleeping bags topped with four or five thick blankets. Before the winter set in, the army had to lay pipes deep into the river, so that they could draw off water for the troops.

Apart from deer, oxen and a few horses, there were few animals. But there were snakes. The most dangerous was the poisonous Bootlace snake; very thin, black and about two feet long. This snake liked to crawl into your boots at night. Rats carried a virus which caused the deadly haemorrhagic fever, and they seemed to be attracted to our steeping bags. Although our Company was free from this infection, there were a few deaths among other units.

Driving was tricky, and the speed limit for trucks was 15 mph (25 kph), and for Jeeps 25 mph (ca 40 kph). I drove a Jeep in winter time, over one of the largest rivers in the country, which was covered in ice, estimated to be four feet thick.

I had only been in Korea five months, when I was sent back to New Zealand to join an officer cadet training unit. This was a very intensive course, attended by 14 cadets of which 10 passed to become officers. I did not want to fail as I was keen to return to Korea. My final leave coincided with Christmas and the Tangiwai train disaster.

Page 33

After receiving my commission I was given command of the Headquarters Platoon in 10 Transport Company. Although the company was in a static position for some time, there was always the concern that we may have to move camp at short notice. Most of the troops had collected or acquired many items that were not issued by the Army. How would they manage?

‘Curly’ Askew, from Gisborne, solved the problem by acquiring a trailer for each of the platoon jeeps. Originally the trailers had belonged to the American forces, which benefited by the exchange of cans of butter and some Kiwi boots. Apparently Kiwi boots were well sought after, as they stood up to the harsh conditions remarkably well.

The ceasefire came in July 1953, and I was sent to the Camp at Inchon for R&R (Rest & Relaxation). This camp was under the control of the British Army and was fairly dilapidated. The tents leaked and the food was very mundane. However, the camp speakers blared out the latest music, and we heard the great news that Edmond [Edmund] Hillary had conquered Mount Everest.

One part of our recreation was to organise a motor rally, teams from the various units of the Commonwealth Divisions competing. Our team of three included a mechanic. We drove nonstop over a 24 hour period, from one side of Korea, over the Taigu Mountains, to the coast. The roads were in a shocking state. Mud slips and driving rain combined to make it a perilous journey. We did not win the rally, but enjoyed the challenge.

After the ceasefire, a number of the local Korean farmers returned to their former land, and with their oxen and ploughs started to cultivate their rice fields. Unfortunately, the American forces had laid a lot of anti-tank mines which were not clearly charted. In the summer, some mines became corroded or overheated, and exploded.

Before returning home in November 1954, I spent some time on liaison duties at the Base Camp in Hiro, Japan. I visited Miajima Island, close to Hiroshima, and saw the devastation that the atom bomb had caused.

My previous job at the New Zealand Electricity Department was waiting for me, but I found it difficult being tied to a desk and each day was somewhat boring. I then decided to join the Police Force.

Page 34

My Lucky Dancing Shoes

Bill Walker, DJX569685

Royal Navy, 5th Support Group

With thanks to David Russell, who helped Bill to sort out his story.

Bill was born and raised in England. When he was a young man, he was employed to help build the Syerston Aerodrome (part of the bomber network). With the same firm, he went on from there to work on another aerodrome, and then a wireless station. It was at this time that he volunteered for the navy, having finally reached the age of eighteen. He was called up in August 1943.

By January 1944, Bill was serving on the HMS Mourne, a near-new 1370 tonne River Class frigate with a crew of 135. The Mourne was part of the escort for a convoy crossing the Atlantic. They were headed to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and set off in agreeable weather.

The following is in Bill’s own words, as he described his first mission:

“Then in mid-Atlantic a storm struck with a vengeance. Mid-winter is notorious on this run, and soon the waves reached gigantic proportions.

“With the atrocious weather pounding the ship, our living conditions up front soon became, one could say, “HELLISH”. The storm lasted for seven days and tested even the most experienced of the crew. By the time we reached St. John’s, we had suffered enough from the elements.

“Once in port there was no rest, just the usual hive of activity, as we cleaned up the mess decks and made our accommodation habitable. It was a bloody shambles, to say the least. The upper deck was a disaster area. We had lost all the life-saving gear and all the immovable gear had been damaged or blown away.”

The US Navy supplied and fitted-out the ship, allowing it to depart with a homeward-bound convoy.

Bill could be forgiven for hoping that negotiating terrible weather was behind him. But as for travelling through the Bay of Biscay, when the Mourne was on outer defence screening duties for the D Day fleet, Bill could only describe the passage as ‘VERY ROUGH’.

Soon enough though, the weather became the least of his worries, pushed to the back of his mind by the demands of battle. Besides, the fateful day of the 15th of June 1944 was a beautiful sunny day.

The previous day, the petty officer had pointed to Bill’s boots. He said that they were too heavy, and would hold a lot of water, sinking a man if he landed into the sea with them on. It made Bill think about his personal safety, and he decided to take a few further precautions.

Page 35

Because his station was located on the bridge, loading one of the six-pound guns, Bill realised that he was relatively far from the locker which held the lifejackets. On the day of 15 June, he took his safety into his own hands. “I pinched a lifejacket and stowed it in the locker next to the gun,” he says. “You weren’t supposed to do that, but I had, and it saved my life.”

Taking the twin precautions of having a lifejacket in hand and changing his footwear (Bill came on deck that historic day wearing his black patent-leather dancing shoes instead of his regulation boots) proved to be the wisest moves of his life.

At 11am the Mourne was hit by an Acoustic Torpedo, fired by the submerged German U-boat 767. This type of torpedo is accurate and lethal, homing in on the throb of a ship’s engine.

“I remember well the vivid and enormous explosion. Fortunately for me my watch-keeping station was on an open platform, open to the elements. Situated just below the bridge, the fact that I was thus exposed, and wearing a lifejacket saved my life. I was blown vertically and out, away from the ship. I landed in an oil-covered sea feet first. That is when my injuries (two broken legs) occurred,” says Bill.

The ship had been broken in half and she sank within 45 seconds from impact. When Bill came up to the surface, after being thrown into the sea, he was just in time to see the stern going down.

The only sign of life on the horizon was one Carley float with a single oar. The sole occupant, one of the ship’s stokers, called out to him. Bill swam up to the float, but couldn’t pull himself in. That was when he first realised that his legs were broken. The two men managed to strap Bill’s wrist to the rope that runs around the outside of the raft. There he stayed until rescue arrived.

“My lifejacket kept me afloat for the next seven hours. Although the sea was cold, it was bearable. Dusk was closing in, and with it my chances of being seen and rescued, would be nil. Then fate took a hand. I was picked up by HMS Aylmer, who had followed our drift from our last position.”

“Never again a dawn will see.

Those ships that day at Normandy.”

Post script: Of the thirty or so souls who were on the bridge when the torpedo struck, Bill was the only survivor.

Page 36

Packing food parcels

Judy Rogers

During World War II, many servicemen were sent food parcels from home. During the conflict, over 20 million standard food parcels were sent. These were always welcome, supplementing rations and renewing the connection with those who were left to carry on everyday life at home. Many parcels were prepared for the troops by women’s groups, but sometimes loving families would send off individually customised food parcels, which could also include hand-knitted socks and hats, books and recreational materials.

Judy remembers that back then she packed such parcels for Norman, who was her husband at that time. She always baked him a fruitcake and shortbread, and included some cigarettes, no matter what else she managed to gather up for him. Sometimes goods were scarce because of rationing, and selections were limited. The whole parcel would be the size of a big plum pudding. “We tried to pack as much as possible into it,” she says.

Her parcels would be sent by sea to Norman, who was stationed in Egypt and Italy, with the New Zealand Army Driving Corp. Parcels took a long time to reach their destination, so could only include foods that kept very well. Sometimes ships were lost at sea, and the cargo was never delivered.

Some of the information about food parcels comes from:

[http:]//n-zealandandaustraliaww2.e-monsite.com/pages/new-zealand-during-world-war-2.html

Page 37

Perils of the Merchant Navy

Amongst the Action with Richard James Blundell

In September 1939 King George VI gave the following speech:

I would like to express to all Officers and Men and in The British Merchant Navy and The British Fishing Fleets my confidence in their unfailing determination to play their vital part in defence. To each one I would say: Yours is a task no less essential to my people’s experience than that allotted to the Navy, Army and Air Force. Upon you the Nation depends for much of its foodstuffs and raw materials and for the transport of its troops overseas. You have a long and glorious history, and I am proud to bear the title “Master of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets”. I know that you will carry out your duties with resolution and with fortitude, and that high chivalrous traditions of your calling are safe in your hands. God keep you and prosper you in your great task.

Jim worked for the County Council, Napier, and had hoped to join the Army. Dr J J Foley had given Jim a full physical medical examination checking him in as A1. Unfortunately, a boyhood accident had left him with impaired vision in his left eye and scuttled his chances of joining the forces.

So Jim did the next best thing and signed up for the Merchant Navy. On 11 May, 1943, at the Napier Wharf, he boarded the MV Port Fairy, a cargo ship belonging to the Port Line Shipping Company. Jim was quite elated when Mr O’Connell, his boss, gave the staff permission to farewell him at the wharf. Jim would now be getting closer to the action.

Photo caption –

MV Port Fairy

[http:]//www.redbubble.com/people/roynz/works/6449159-m-v-port-fairv-a-blast-from-the-past

Page 38

Jim maintains that the heroic catch-phrase that men joined up for God, for King and country was all bull-s..t; they joined up purely for the adventure.

The Master of the ship, Captain John Lewis from Wolverhampton, England, was thoroughly respected by the British officers and crew. He was very fair-minded and would listen to both sides of a story, should any issues arise. One order which crew members always obeyed was to wear life jackets when on deck.

The Merchant Navy ships were of great importance to the Allies, sailing through dangerous enemy waters, loading and unloading much-needed provisions from ports world-wide. The cargo would mainly consist of rations, radio parts, ammunition and drums of high-octane petrol for the Royal Air Force, to name a few.

On 9 July 1943, a convoy comprising the MV Port Fairy, HMS troopships Duchess of York and California with HMS escorts Iroquois, Douglas and Moyla, sailed for Freetown, Sierra Leone. Two days later, near the Bay of Biscay, there was a sustained attack by three German Focke-Wulf aircraft.

The bombing left both troopships blazing. Ropes from the MV Port Fairy were thrown overboard in the hope of rescuing some survivors. The damaged vessels were torpedoed by the escort ships in the hope that the blaze would discourage further attention from the U-boats.

Jim commented that the Luftwaffe pilots were masters of their trade. It was reported that more than 100 of the seamen were killed.

The MV Port Fairy was lucky to be left unscathed, but only for a further day, when it was damaged in a second attack. The HMS Swale, a frigate returning from Gibraltar, became the escort vessel as the MV Port Fairy made her way to Casablanca, but this was not to be smooth sailing. The two ships were attacked and the MV Port Fairy was hit on the port quarter by a 50kg bomb which breached the hull and disabled her steering. Jim, who was both the refrigeration engineer and fireman, was now really amongst the action. Ammunition in cargo spaces was jettisoned and compartments flooded. The crew set up a bucket chain to douse the fire.

Many cabins had been destroyed and when it was safe for Jim to return to his cabin, another surprise awaited him. There he found a sailor on his bunk that had spotted the bottle of whisky Jim had bought for his dad. His words to Jim were “Come on Kiwi, open the bottle because we won’t be here tomorrow!” Obviously they were still there “tomorrow” and Jim’s dad missed out.

The MV Port Fairy, with only partial steering, was able to limp in to Casablanca, now under American control. It was first estimated the ship would be ready for sailing in three weeks but it was actually three months to the day.

One evening Jim and some of his mates, returning to base, missed the curfew, which according to Jim was ridiculously early – something like 9.30 or 10pm. This meant an appearance before the Officer-in-Charge and a reprimand. Jim thought it was all a bit of a joke until he was confronted by the officer whipping out a gun from his holster and slamming it on the desk, remarking “You beat this and you beat me.”