Country Life

Along The Ghost Road Of The Inland

By Lester Masters

BACK in pioneering times before the opening of the Main Trunk railway, the Inland Patea road was practically the only access route for the huge area of country stretching westward across the ranges from Hawke’s Bay to the bushlands of the Wanganui River and northward almost to the shores of Lake Taupo.

Along it in those picturesque times, raced the stage coaches of the rival firms of MacDonald and Rhymer [Rymer]; and down it first on strings of packhorses and later on bullock and horse waggons came, probably a greater wealth of wool than was carried by any other of the main roads of the North Island. Along the route at widely spaced intervals, to cater for the needs of travellers, settlers and workers, were hotels, post office stores, stables, blacksmiths and bookmakers’ shops.

Apart from a few old buildings and clumps of trees marking the sites of others, all these things have now vanished. Today the old road to the Inland has become more or less of a ghost road. Large sections of the original route have long since become a thing of the past. For the few inhabitants who now dwell along its central 23-mile section there is no regular mail service, nor for six months of the year is any vehicle of over two tons in weight allowed over that section without a special licence.

The Founders

OWING to records having been destroyed in a fire following the disastrous Hawke’s Bay earthquake of 1931, little definite information is now obtainable on the early history of the Island. It would seem, however, from what information I have been able to gather, that the brothers Azim and William Birch were probably the founders of the sheep-raising industry in that area. Sometime in the 1860’s they crossed the ranges from Hawke’s Bay with a small flock of sheep and took up a large tract of land lying between the upper reaches of the Rangitikei and Mowhango [Moawhango] Rivers. Erewhon Station was the name they gave to their holding. Certainly to them at that time, that place must have seemed nowhere. At one stage the brothers were reputed to have had 80,000 sheep grazing on Erewhon.

The route taken by the brothers on that epic first drive was along the old Maori war trail leading up the bed of the Ngaruroro River to Whana Whana, then through Glenross and Omahaki, across the low saddle between the Burns Range and Kohinga to the Ngaruroro crossing at Kurapapaungo, and from there by much the same route as is followed by the present road.

The section of the route up the Ngaruroro to Glenross was later replaced by one up the Tutaekuri River and along the foot of the range to Glenross and then on. Later again the section from the foot of the Blowhard and on through Omahaki to Kurapapauugo [Kuripapango] was replaced by a track over the Blowhard. Eventually the route up the Tutaekuri was abandoned and replaced by the present one through Sherenden. Old-timers tell me that in the early days the Omahaki route was used to a certain extent by bullock drays.

One yarn I have heard tell of the old Omahaki track, concerned a drover and his boy assistant. The pair, while on their way through to the Inland with a mob of 50 rams, pulled in for the night at one of the camp sites. It had been a hot, tiring day, and the billy had been packed away with other gear in the pack. Bill, the drover, sent the boy down to the creek to get some water in one of the empty bottles he knew would be down there. The boy seemed a long time gone.

“Hey!” Bill yelled, “What the heck are you doing?”

“The only sound bottle I can find is full of something and it’s corked and sealed. I’m looking for a sharp stone to knock the top off.” responded the boy.

“Stop! Stop! Don’t do that,” roared Bill. “Bring it up quick and be careful with it. I’ll soon get the cork out.”

Which, on the boy’s arrival, Bill smartly set to work and did. He gave a sniff, a pleased grin came over his face. He raised the bottle to his lips and took a good swig. It was whisky all right. How it had come to be where the boy had found it he did not know or care.

Crowded Out

HE took a couple more good swigs, lit his pipe and stamped off to count the rams, just to make sure none had strayed on route. Sixty was what he made the tally, a gain of 10 and there did not appear to be any strangers among them. He had another go at the bottle and tried again. This time the tally went up to 100. He decided to go back to the bottle before the rams started to crowd him out and leave the tallying until morning.

When morning did come, Bill was not feeling very well. He heaved the empty bottle away, broke camp and counted the rams out. The tally had reverted to the original 50. Apparently the extra 50 had come and gone with the whisky bottle.

The Omahaki trail may still be traced by clumps of trees planted by old timers. As for the bottles, they have all vanished. I know because I have looked.

Glendinny and Griffin, a Napier firm, were responsible for the construction of a large portion of the Inland Patea road. By 1880 the road had reached Kurapapaungo. In 1882 the first of the two hotels, one on the eastern side of the river belonging to Mr Kinross, a Napier merchant, and one on the western side of the river belonging to Mr Alex MacDonald, were opened. In 1883 Mr MacDonald had a pedestrian swing bridge erected over the Ngaruroro River. A low-level traffic bridge was also erected over the river that year. This bridge was swept away during the 1897 flood and the present one then erected. The swing bridge was later taken down and re-erected over the Rangitikei River.

Maori Bullocky

BY 1884 the road had reached Moawhango. At this time there were also two other hotels further down the road. One at Waikonini, about a mile down the then Tutaekuri Valley Road from where the Waiwhare station homestead now stands, and the other at Konini, about another six miles down the road. Not one of these hotels, or the accompanying stores, blacksmiths’ shops, stables, etc. is now in existence. The one-time accommodation houses and horse-changing places for the stage coaches at the Konini Creek crossing at Willowford, at the foot of the Blowhard and on the western side of the Ngaruroro, have also gone.

There was an accommodation house at the Rangitikei River crossing. It was owned by a Maori bullocky named Johnny Kelly. It was later taken over by Mr Williams, a waggoning contractor. It is still in existence and is now an out-station of Mr J. B. Campbell’s Otupae station.

Johnny Kelly, the Maori Bullocky, was something of a character. At one stage he was brought before the Court for sly grog selling. He indicated that he wanted an interpreter as he could not speak English. When the constable gave evidence against him, however, Johnny jumped up and said it was all a lot of – lies. The magistrate straight away stood the interpreter down and sentenced Johnny.

On one of his trips through with his waggon, while yet some distance up the Gentle Annie, Johnny lagged behind to have a yarn with some other Maoris. His attention was suddenly drawn to the fact that his team was drifting dangerously near to the edge of a drop of hundreds of feet. He rushed along the danger side with the idea of forcing […] the road. One of the bullocks lurched his way and sent him over the drop, known since, by the way, as Kelly’s Mistake.

Mr MacDonald and some of his guests at the hotel noticed the accident and rushed down along the river bed to where Johnny had fallen, fully expecting to find him dead. Johnny, however, had gone down a shingle slide. He was badly bruised and cut about, but had no bones broken. He was taken to the Napier Hospital. While there his wife Annie visited him. When she sat on the bed for a talk, the bed collapsed. The combined weight of the pair was 35 stone.

Early Prices

JOHNNY, after surviving that fall of hundreds of feet on to the rocky bed of the Ngaruroro, met his fate as an old man in 1917 at Omahu, near Fernhill, in a simple way. While driving along the road with his horse and gig, he offered a school child a lift. As he bent down to help the child on board he overbalanced, fell forward on to the road and died of a broken neck.

I have an old hotel cashbook, loaned me by the Knolls family, present owners of what was once the Konini Hotel farm. In view of today’s conditions it makes interesting reading. Here are a few extracts:

February 4, 1889, bought off Mr F. S. Waterhouse, 20 fat wethers, 3d a head; March 16, 1889, R. Anderson, tea, bed and breakfast, 4s 6d; December, 1888, F. Healy, 2 gallons over proof whisky, £3; R. Sutherland, tea, bed and breakfast, 4s 6d; paddocking six horses, 6s; Alex MacDonald dinner, 1s 6d; February, 1889, M. Shields, one bottle whisky, 7s; Jas. Alexander, tea, bed and breakfast, 4s 6d; Two pounds tobacco, 14s; matches 3s; R. Anderson, tea, bed and breakfast, 4s 6d; one pound tobacco, 7s; one bottle gin, 7s. Left for Patea with bullock team; G. Rhymer, three horse feeds ..

All drink at the bar, either beer or spirits, were apparently 6d, and these were the days of pints of beer and bottle on the counter with spirits.

Before the formation of bullock tracks and safer roads, the wool from Whana Whana, Glenross and all points west and north to as far back as Karioi at the foot of Mt Ruapehu, was transported by teams of pack horses. But the stories of those times and of the bullock and horse waggons and racing stage coaches I must now leave until some other time.

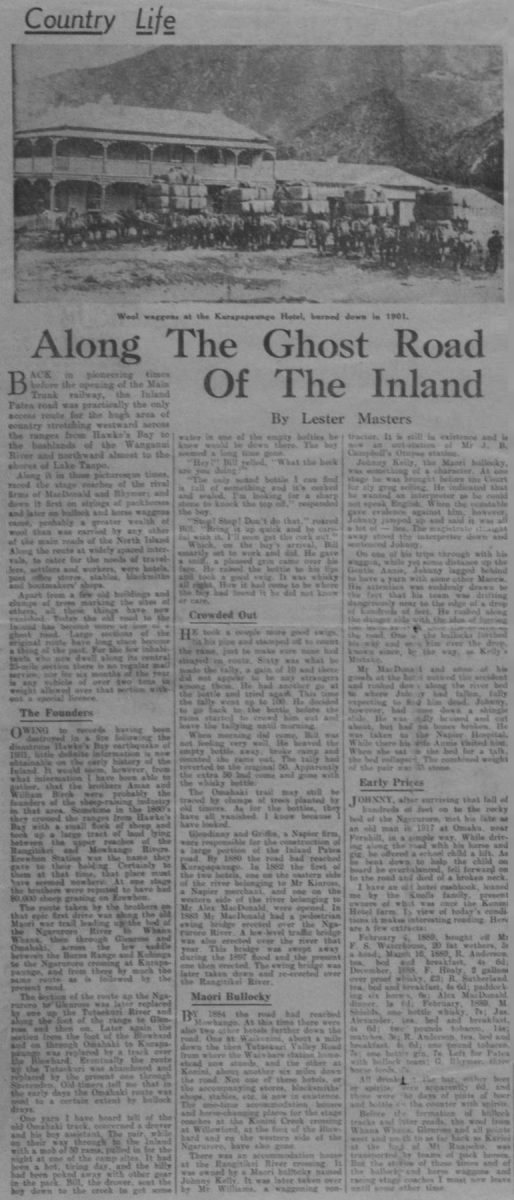

Photo caption – Wool waggons at the Kurapapaungo [Kuripapango] Hotel, burned down in 1901.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.