Book page

Fascinating glimpses of old Hawke’s Bay

“Old Wairoa” is a marvellous book and worth every cent of the $40 price tag.

Thomas Lambert was an Irishman who came to New Zealand from Galway in 1875 at the age of 21. He became a journalist and editor of the Wairoa Guardian and the East Coast Mail.

In his retirement he wrote a book titled “The Story of Old Wairoa and the East Coast District, North Island, New Zealand, or Past, Present and Future.” It was described as a record of over 50 years progress, with preface and dedicatory note, all profusely illustrated.

For many years the book has been a collectors’ item and library treasure and now Capper Press have produced a reprint issue.

The author was happily untroubled by the accepted methods of literary historians. In his book he presents fact and information and embroiders it with speculation and imagination.

He starts with a flight of fantasy to bring his reader into Wairoa by sea over “the heaving bosom of the blue Hawke’s Bay waters. “Our sails are flapping and our blocks are creaking, the dark pall of night hangs over us, the orb of day has not yet risen, we brace up for a tack to windward toward the everlasting hills etc.

And so into Old Wairoa through a sea of purple prose. Over the bar and up the river to a vivid description of a Maori village, its sights, sounds and smells much romanticised.

It is like starting a Victorian novel rather than a book of history. I loved it. Thomas Lambert snared one enthusiastic reader. And I did not know then that his terminal flight of fancy was to be even more purple.

The beginning

He begins at the beginning. Right at the beginning. In a chatty way he outlines the various theories of New Zealand’s origin. Those who have other geological possibilities are challenged to go out with bag and hammer, gather specimens and prove it if they can.

Lambert speculates on the existence of a great southern continent and a continent stretching from America to Asia; on the earth movements that caused the land masses to subside and submerge and reappear through the ages. He puts forward various theories for migration relating to hemispherical changes as the earth from time to time swung too far on its axis and precipitated cataclysm. Lambert specialises in fascinating little tangent journeys and he suggests that the spiral that is the base of Maori art is related to the solar motion of the earth.

On local geology the author quotes from Henry Hill, once Mayor of Napier, favourite speaker and writer of scientific papers.

Lambert again gives way to the temptation of lapsing into fantasy as he describes the subsidence of the great plain that once connected Mahia with Cape Kidnappers. In terrible volcanic and earthquake activity the plain was engulfed and all its pre-Maori inhabitants drowned as the sea swept in to its present line at the base of Scinde Island, Mohaka and Wairoa.

Speculation

The old story of why-the-whales-come-to-Mahia is put forward again, based on the belief that the Mahia Peninsula was once part of the land mass and cut by a river. Through this strait lay the “whale route,” the path of the migrating whales. It is suggested that migrating whales still look for this short cut and then follow the coast around Portland Island.

Lambert, writing in pre-earthquake days of the 1920s, suggests that what has happened many times in the past could happen again at any time and a further subsidence could drown out the coast towns and take them to the bed of the ocean – or an upthrust could draw back the sea and return some land.

In an interesting survey of the various theories of the place origin of the Maori race, Lambert comes down firmly in favour of India as the cradle of the human race. He puts the rest of us down in the same place – of a common stock.

History

“OLD WAIROA,” by T. Lambert; Capper Press; 802 pages; $40; our copy from the publishers. Review by Kay Mooney.

The legends

The New Zealand migration myths and legends are examined in detail and it is obvious that Lambert, the Irishman, has a special fancy for the traces of the fairy people of New Zealand, the white-skinned, red-haired, gentle people who retreated into the mountains before the fierce invaders and who were often heard but rarely seen. Were these pre-Polynesian people fact or fantasy? Where did the red-headed Maoris of the East Coast and the Urewera come from?

The book looks at Maori custom and religion, gives a comprehensive list of Wairoa district pa sites and one chapter deals with the story of the moa, complete with a very good map of moa-bone findings. The wars between Maori tribes, coming of the settlers, the Hauhau wars and rebellions are detailed and clear and full of snippets of new information.

There is a particularly good account of the Te Kooti story. In it, Karanama Ngerengere is mentioned as Te Kooti’s lieutenant but the author does not refer to a claim he must have heard, for it was common at one time, that the real Te Kooti was killed at Mohaka and that Ngerengere took over the name and the identity.

After this detailed account of the fighting, down to the final skirmishes, the story of Wairoa’s development in freezing and dairying and flax-dressing, its local bodies, musical societies, hospital and P. and T. fall a little flat.

The fascinating story of land buying and land deals is not touched upon. In 1925 it was still safely under the carpet.

Prophetic

However, the final chapter is a wonderful note on which to end a book. It is a prophetic look into the future of Wairoa. It was written in 1925 and the author was obviously on fire with hope for a hydro-electric future for New Zealand and captivated by the romance of a brave new world that was all-electric.

He looks ahead to 1975 and through the eyes of a Rip van Winkle who fell into shock at the thought of a £100,000 hydro-power loan, he describes the new Wairoa.

Waikaremoana is supplying power to the whole North Island. Wairoa has ousted Gisborne in importance. Morere is a prosperous spa town. Waikokopu is a busy overseas harbour.

Mahia is the Brighton of New Zealand and Opoutama is a seaside town with shops and cinemas and crowded ferries bringing in the day-trippers.

Electric trains run in all directions and cars speed along smooth roads cheaply made from the abundant papa clay. Ferry steamers down Wairoa run up and down Wairoa river to the extensive town and wharves.

At the Wairoa heads is a fashionable suburb, the Elysium. It was laid out by the harbour board when the outer harbour was built (£100,000 loan).

In Wairoa town, Marine Parade is occupied by banks and importing houses. The buildings are all of permanent material—the city council supplying shingle at 2/6d a yard as well as bricks from the municipal brickworks.

The many industries of the town show New Zealand as the factory of the Pacific, keeping her raw products and selling them processed. Cheap water power has made competition with China and Japan possible. It is hoped that soon hydro power will be superseded by power from the air and from the atom.

People do not walk to the shops. They fly along with small electric wing motors strapped on.

Agricultural projects abound, superphosphate is free and noxious weeds have been eradicated.

Much of it has not yet come. Much of it did – but not in Wairoa.

It is clear that many subsequent histories have called heavily upon Old Wairoa. Its coverage of the Maori tribal wars and also the land wars is excellent.

It is indeed profusely illustrated as claimed. Not least among the illustrations are the imaginative drawings of Wairoa in 1975 – the extensive harbours and beautiful gardens that existed only in the mind of the author.

Only the most carping of readers will object to imaginary descriptions cropping up in the middle of sober historical fact.

Attitudes

One interesting aspect of Old Wairoa is the glimpse it gives into the mental attitudes of the New Zealander of 50 years ago. It could be South Africa today in its paternalist attitude to the minority group.

Lambert deplores the deterioration of the Maori from the status of noble warrior to pool-playing and cinema-going layabout. He seems assured that the Maori race in the 1920s is done for. However, he puts forward a hopeful vision, most of it brought about by an enlightened policy for Wairoa College.

Maoris, though not entirely weaned from their love of sport, have taken very kindly to the gospel of work and have become thoroughly Europeanised with an improvement in physique and constitution. Inter-marriage between half-castes is prohibited and pure-bred Maoris now marry their like to produce a fine type of individual, in his vision.

Old Wairoa is a book well worth preserving. It is a pity the cost had to be so high but when compared to what $40 can buy today in any other shop, it will be agreed that the booksellers are offering a treasure here.

Photo captions –

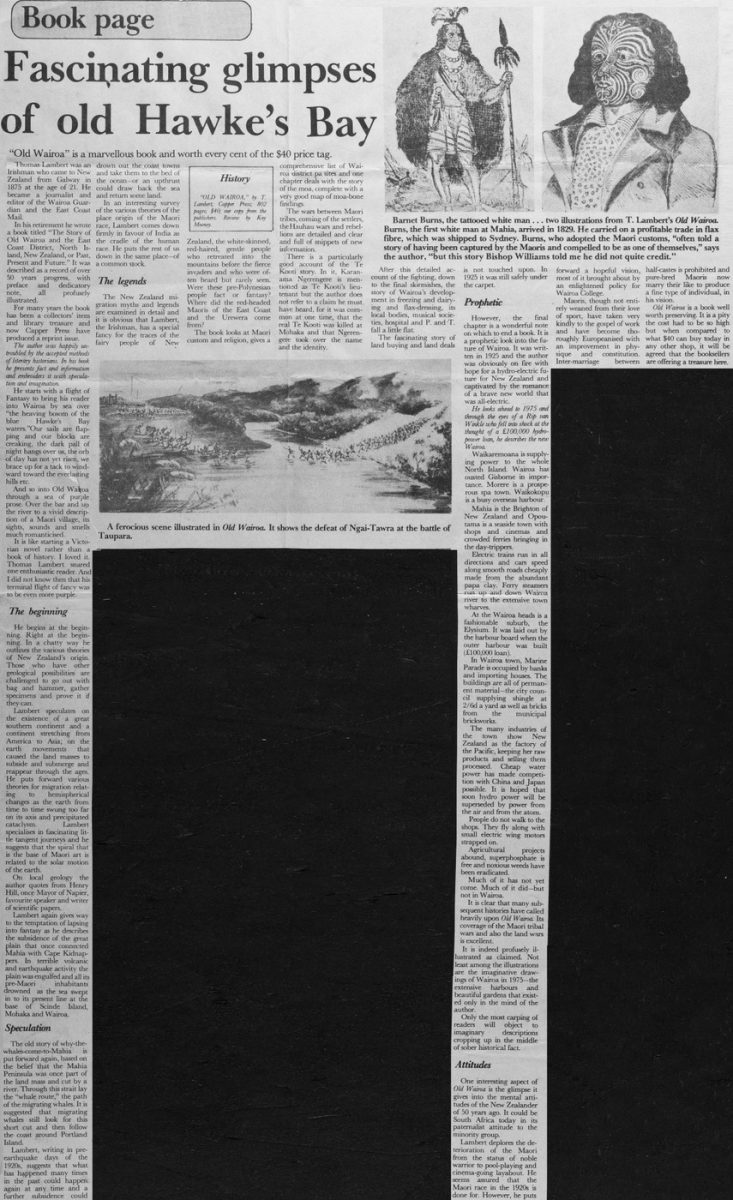

A ferocious scene illustrated in Old Wairoa. It shows the defeat of Ngai-Tawra [Nga ti-Tauira] at the battle of Taupara.

Barnet Burns, the tattooed white man … two illustrations from T. Lambert’s Old Wairoa. Burns, the first white man at Mahia, arrived in 1829. He carried on a profitable trade in flax fibre, which was shipped to Sydney. Burns, who adopted the Maori customs, “often told a story of having been captured by the Maoris and compelled to be as one of themselves,” says the author, “but this story Bishop Williams told me he did not quite credit.”

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.