Quake survivors tell their stories

Doctor’s skills were vital

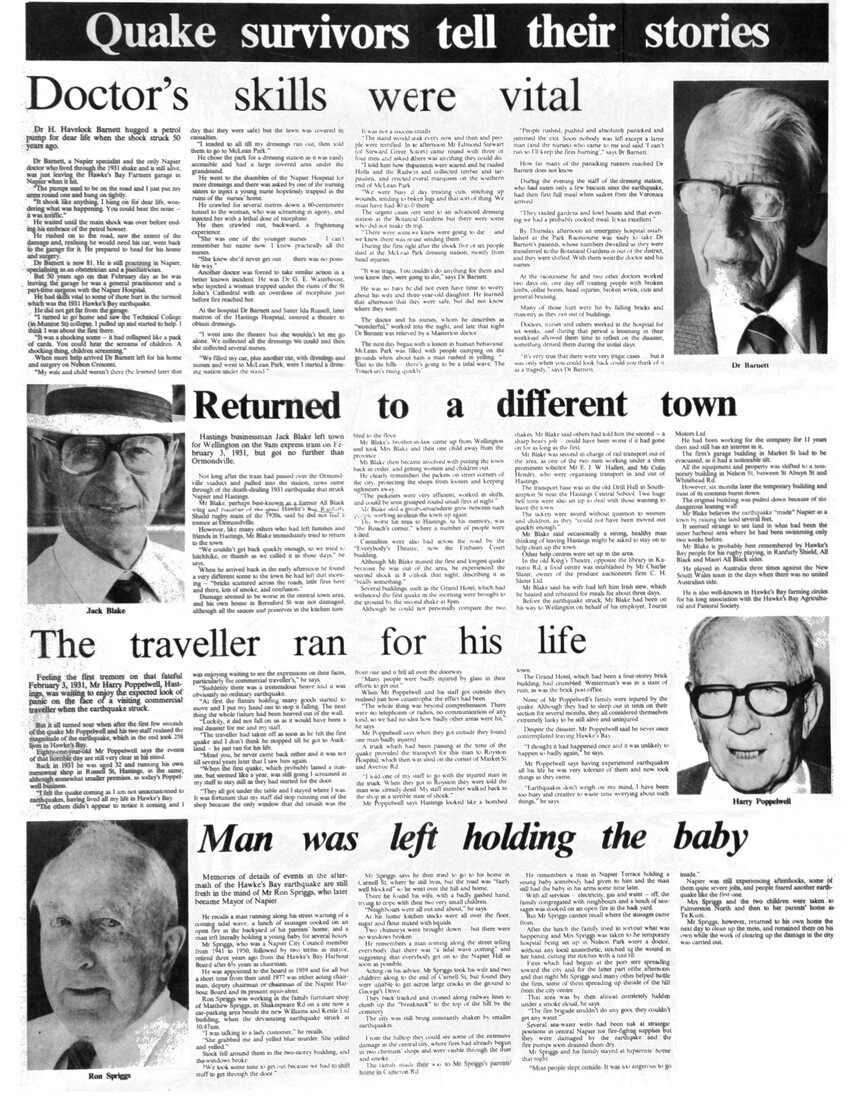

Dr. H. Havelock Barnett hugged a petrol pump for dear life when the shock struck 50 years ago.

Dr Barnett, a Napier specialist and the only Napier doctor who lived through the 1931 shake and is still alive, was just leaving the Hawke’s Bay Farmers garage in Napier when it hit.

“The pumps used to be on the road and I just put my arms round one and hung on tightly.

“It shook like anything. I hung on for dear life, wondering what was happening. You could hear the noise – it was terrific.”

He waited until the main shock was over before ending his embrace of the petrol bowser.

He rushed on to the road, saw the extent of the damage and realising he would need his car, went back to the garage for it. He prepared to head for his home and surgery.

Dr. Barnett is now 81. He is still practising in Napier, specialising as an obstetrician and a paediatrician.

But 50 years ago on that February day as he was leaving the garage he was a general practitioner and a part-time surgeon with the Napier Hospital.

He had skills vital to some of those hurt in the turmoil which was the 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake.

He did not get far from the garage.

“I turned to go home and saw the Technical College (in Munroe St) collapse. I pulled up and started to help. I think I was about the first there.

“It was a shocking scene – it had collapsed like a pack of cards. You could hear the screams of children. A shocking thing, children screaming.”

When more help arrived Dr Barnett left for his home and surgery on Nelson Crescent.

“My wife and child weren’t there (he learned later that day that they were safe) but the lawn was covered in casualties.

“I tended to all till my dressings ran out, then told them to go to McLean Park.”

He chose the park for a dressing station as it was easily accessible and had a large covered area under the grandstand.

He went to the shambles of the Napier Hospital for more dressings and there was asked by one of the nursing sisters to inject a young nurse hopelessly trapped in the ruins of the nurses’ home.

He crawled for several metres down a 60-centimetre tunnel to the woman, who was screaming in agony, and injected her with a lethal dose of morphine.

He then crawled out backward, a frightening experience.

“She was one of the younger nurses … I can’t remember her name now. I knew practically all the nurses.

“She knew she’d never get out … there was no possible way.”

Another doctor was forced to take similar action in a better known incident. He was Dr G. E. Waterhouse, who injected a woman trapped under the ruins of the St. John’s Cathedral with an overdose of morphine just before fire reached her.

At the hospital Dr Barnett and Sister Ida Russell, later matron of the Hastings Hospital, entered a theatre to obtain dressings.

“I went into the theatre but she wouldn’t let me go alone. We collected all the dressings we could and then she collected several nurses.

“We filled my car, plus another car, with dressings and nurses and went to McLean Park, where I started a dressing station under the stand.”

It was not a success initially.

“The stand would creak every now and then and people were terrified. In the afternoon Mr Edmond Stewart (of Stewart Greer) came round with three or four men and asked if there was anything they could do.

“I told him how the patients were scared and he raided Holts and the Railways and collected timber and tarpaulins, and erected several marquees on the southern end of McLean Park.

“We were busy all day treating cuts, stitching up wounds, tending to broken legs and that sort of thing. We must have had 40 to 50 there.”

The urgent cases were sent to an advanced dressing station at the Botanical Gardens but there were some who did not make the trip.

“There were some we knew were going to die – and we knew there was no use sending them.”

During the first night after the shock five or six people died at the McLean Park dressing station, mostly from head injuries

“It was tragic. You couldn’t do anything for them and you knew they were going to die,” says Dr Barnett.

He was so busy he did not even have time to worry about his wife and three-year-old daughter. He learned that afternoon that they were safe, but did not know where they were.

The doctor and his nurses, whom he describes as “wonderful,” worked into the night, and late that night Dr Barnett was relieved by a Masterton doctor.

The next day began with a lesson in human behaviour. McLean Park was filled with people camping on the grounds when about 6am a man rushed in yelling “Get to the hills – there’s going to be a tidal wave. The Tutaekuri’s rising quickly.”

“People rushed, pushed and absolutely panicked and jammed the exit. Soon nobody was left except a lame man (and the nurses) who came to me and said ‘I can’t run so I’ll keep the fires burning’,” says Dr Barnett.

How far many of the panicking runners reached Dr Barnett does not know.

During the evening the staff of the dressing station, who had eaten only a few biscuits since the earthquake, had their first full meal when sailors from the Veronica arrived.

“They raided gardens and fowl houses and that evening we had a probably [properly] cooked meal. It was excellent.”

By Thursday afternoon an emergency hospital established at the Park Racecourse was ready to take Dr Barnett’s patients, whose number dwindled as they were transferred to the Botanical Gardens or out of the district, and they were shifted. With them went the doctor and his nurses.

At the racecourse he and two other doctors worked two days on, one day off treating people with broken limbs, collar bones, head injuries, broken wrists, cuts and general bruising.

Many of those hurt were hit by falling bricks and masonry as they ran out of buildings.

Doctors, nurses and others worked at the hospital for six weeks, and during that period a lessening in their workload allowed them time to reflect on the disaster, something denied them during the initial days.

“Its very true that there were very tragic cases … but it was only when you could look back could you think of it as a tragedy,” says Dr Barnett.

Photo caption – Dr Barnett

Returned to a different town

Hastings businessman Jack Blake left town for Wellington on the 9am express train on February 3, 1931, but got no further than Ormondville.

Not long after the train had passed over the Ormondville viaduct and pulled into the station, news came through of the death-dealing 1931 earthquake that struck Napier and Hastings.

Mr Blake, perhaps best known as a former All Black wing and member of the great Hawke’s Bay Ranfurly Shield rugby team of the 1920s, said he did not feel a tremor at Ormondville.

However, like many others who had left families and friends in Hastings, Mr Blake immediately tried to return to the town.

“We couldn’t get back quickly enough, so we tried to hitchhike or thumb as we called it in those days,” he says.

When he arrived back in the early afternoon he found a very different scene to the town he had left that morning – “bricks scattered across the roads, little fires here and there, lots of smoke, and confusion.”

Damage seemed to be worse in the central town area, and his own house in Beresford St was not damaged, although all the sauces and preserves in the kitchen tumbled to the floor.

Mr Blake’s brother-in-law came up from Wellington and took Mrs Blake and their one child away from the province.

Mr Blake then became involved with putting the town back in order, and getting women and children out.

He clearly remembers the pickets on street corners of the city, protecting the shops from looters and keeping sightseers away.

“The picketers were very efficient, worked in shifts, and could be seen grouped around small fires at night.”

Mr. Blake said a great camaraderie grew between such people, working to clean the town up again.

The worst hit area in Hastings, to his memory, was “the Roach’s corner,” were a number of people were killed.

Casualties were also bad across the road by the “Everybody’s Theatre,” now the Embassy Court building.

Although Mr Blake missed the first and longest quake because he was out of the area, he experienced the second shock at 8 o’clock that night, describing it as “really something.”

Several buildings, such as the Grand Hotel, which had withstood the first quake in the morning were brought to the ground by the second shake at 8pm.

Although he could not personally compare the two shakes, Mr Blake said others had told him the second – a sharp heavy jolt – could have been worse if it had gone on for as long as the first.

Mr Blake was second in charge of rail transport out of the area, as one of the two men working under a then prominent solicitor Mr E. J. W. Hallett, and Mr Colin Hendry, who were organising transport in and out of Hastings.

The transport base was in the old Drill Hall in Southampton St near the Hastings Central School. Two huge bell tents were also set up to deal with those wanting to leave town.

The tickets were issued without question to women and children, as they “could not have moved out quickly enough.”

Mr Blake said occasionally a strong, healthy man thinking of leaving Hastings might be asked to stay on to help clean up the town.

Other help centres were set up in the area.

In the old King’s Theatre, opposite the library in Karamu Rd, a food centre was established by Mr Charlie Slater, owner of the produce auctioneers firm C. H. Slater Ltd.

Mr Blake said his wife had left him Irish stew, which he heated and reheated for meals for about three days.

Before the earthquake struck, Mr Blake has been on his way to Wellington on behalf of his employer, Tourist Motors Ltd.

He had been working for the company for 11 years then and still has an interest in it.

The firm’s garage building in Market St had to be evacuated, as it had a noticeable tilt.

All the equipment and property was shifted to a temporary building in Nelson St, between St Aubyn St and Whitehead Rd.

However, six months later the temporary building and most of its contents burnt down.

The original building was pulled down because of the dangerous leaning wall.

Mr Blake believes the earthquake “made” Napier as a town by raising the land several feet.

It seemed strange to see land in what had been the inner harbour where he had been swimming only two weeks before.

Mr Blake is probably best remembered by the Hawke’s Bay people for his rugby playing, in Ranfurly Shield, All Black and Maori All Black sides.

He played in Australia three times against the New South Wales team in the days when there was no united Australian side.

He is also well-known in Hawke’s Bay farming circles for his long association with the Hawke’s Bay Agricultural and Pastoral Society.

Photo caption – Jack Blake

The traveller ran for his life

Feeling the first of the tremors on that fateful February 3, 1931, Mr. Harry Poppelwell, Hastings, was waiting to enjoy the expected look of panic on the face of a visiting commercial traveller when the earthquake struck.

But it all turned sour when after the first few seconds of the quake Mr Poppelwell and his two staff realised the magnitude of the earthquake, which in the end took 258 lives in Hawke’s Bay.

Eighty-one-year-old Mr Poppelwell says the events of that horrible day are still very clear in his mind.

Back in 1931 he was aged 32 and running his own menswear shop in Russell St, Hastings, in the same although somewhat smaller premises, as today’s Poppelwell business.

“I felt the quake coming as I am not unaccustomed to earthquakes, having lived all my life in Hawke’s Bay.

“The others didn’t appear to notice it coming and I was enjoying waiting to see the expressions on their faces, particularly the commercial traveller’s,” he says.

“Suddenly there was a tremendous heave and it was obviously no ordinary earthquake.

“At first the fixture holding many goods started to move and I put my hand out to stop it falling. The next thing the whole fixture had been heaved out of the wall.

“Luckily, it did not fall on us as it would have been a real disaster for me and my staff.

“The traveller had taken off as soon as he felt the first quake and I don’t think he stopped till he got to Auckland – he just ran for his life.

“Mind you, he never came back either and it was not till several years later that I saw him again.

“When the first quake, which probably lasted a minute, but seemed like a year, was still going I screamed at my staff to stay still as they had started for the door.

“They all got under the table and I stayed where I was. It was fortunate that my staff did stop running out of the shop because the only window that did smash was the front one and it fell over the doorway.

“Many people were badly injured by glass in their efforts to get out.”

When Mr Poppelwell and his staff got outside they realised just how catastrophic the effect had been.

“The whole thing was beyond comprehension. There were no telephones or radios, no communication of any kind, so we had no idea how badly other areas were hit,” he says.

Mr Poppelwell says when they got outside they found one man badly injured.

A truck which had been passing at the time of the quake provided the transport for this man to Royston Hospital, which then was sited on the corner of Market St and Avenue Rd.

“I told one of my staff to go with the injured man in the truck. When they got to Royston they were told the man was already dead. My staff member walked back to the shop in a terrible state of shock.”

Mr Poppelwell says Hastings looked like a bombed town.

The Grand Hotel which had been a four-storey brick building, had crumbled. Westerman’s was in a state of ruin, as was the brick post office.

None of Mr Poppelwell’s family were injured by the quake. Although they had to sleep out in tents on their section for several months, they all considered themselves extremely lucky to be still alive and uninjured.

Despite the disaster, Mr. Poppelwell said he never once contemplated leaving Hawke’s Bay.

“I thought it had happened once and it was unlikely to happen so badly again,” he says.

Mr Poppelwell says having experienced earthquakes all his life he was very tolerant of them and now took things as they came.

“Earthquakes don’t weigh on my mind. I have been too busy and creative to waste time worrying about such things,” he says.

Photo caption – Harry Poppelwell

Man was left holding the baby

Memories of details of events in the aftermath of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake are still fresh in the mind of Mr Ron Spriggs, who later became Mayor of Napier.

He recalls a man running along his street warning of a coming tidal wave; a lunch of sausages cooked on an open fire in the backyard of his parents’ home; and a man left literally holding a young baby for several hours.

Mr Spriggs, who was a Napier City Council member from 1941 to 1950, followed by two terms as mayor, retired three years ago from the Hawke’s Bay Harbour Board after 6 1/2 years as chairman.

He was appointed to the board in 1959 and for all but a short term from then until 1977 was either acting chairman, deputy chairman or chairman of the Napier Harbour Board and its present equivalent.

Ron Spriggs was working in the family furniture shop of Matthew Spriggs, in Shakespeare Rd on a site now a car-parking area beside the new Williams and Kettle Ltd building, when the devastating earthquake struck at 10.47am.

“I was talking to a lady customer,” he recalls.

“She grabbed me and yelled blue murder. She yelled and yelled.”

Stock fell around them in the two-storey building, and the windows broke.

“We took some time to get out because we had to shift stuff to get through the door.”

Mr Spriggs says he then tried to go to his home in Carnell St, where he still lives, but the road was “fairly well blocked” so he went over the hill and home.

“Neighbours were all out and about,” he says.

At his home kitchen stocks were all over the floor, sugar and flour mixed with liquids.

Two chimneys were brought down – but there were no windows broken.

He remembers a man coming along the street telling everybody that there was a “tidal wave coming” and suggesting that everybody get on to the Napier Hill as soon as possible.

Acting on his advice, Mr Spriggs took his wife and two children along to the end of Carnell St, but found they were unable to get across large cracks in the ground to George’s Drive.

They back-tracked and crossed along railway lines to climb up the “breakneck” to the top of the hill by the cemetery.

The city was still being constantly shaken by smaller earthquakes.

From the hilltop they could see some of the extensive damage in the central city, where fires had already begun in two chemists’ shops and were visible through the dust and smoke.

The family made their way to Mr Spriggs’ parents’ home in Cameron Rd.

He remembers a man in Napier Terrace holding a young baby somebody had given to him and the man still had the baby in his arms some time later.

With all services – electricity, gas and water – off, the family congregated with neighbours and a lunch of sausages was cooked on an open fire in the back yard.

But Mr Spriggs cannot recall where the sausages came from.

After the lunch the family tried to sort out what was happening and Mrs Spriggs was taken to the temporary hospital being set up in Nelson Park where a doctor, without any local anaesthetic, stitched up the wound in her hand, cutting the stitches with a nail file.

Fires which had begun at the port were spreading toward the city and for the latter part of the afternoon and that night Mr Spriggs and many others helped battle the fires, some of them spreading up the side of the hill from the city centre.

That area was by then almost completely hidden under a smoke cloud, he says.

“The fire brigade couldn’t do any good, they couldn’t get any water.”

Several sea-water wells had been sunk at strategic positions in central Napier for fire-fighting supplies but they were damaged by the earthquake and the fire pumps soon drained them dry.

Mr Spriggs and his family stayed at his parents’ home that night.

“Most people slept outside. It was too dangerous to go inside.”

Napier was still experiencing aftershocks, some of them quite severe jolts, and people feared another earthquake like the first one.

Mrs Spriggs and the two children were taken to Palmerston North and then to her parents’ home in Te Kuiti.

Mr Spriggs, however, returned to his home the next day to clean up the mess, and remained there on his own while the work of clearing up the damage in the city was carried out.

Photo caption – Ron Spriggs

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.