As enemies they met under the clouds of war

45 years on they’re still mates

Staff reporter Roger Moroney continues the story of a unique friendship forged from an enemy encounter

Old times were relived and memories were rekindled

John Caulton, sitting in the midst of several German troops and accepting the notion that for him the war had ended, came face to face with a smartly attired Luftwaffe Major and his two aircrew from an ME1I0.

He recalls how well-dressed the three were, thinking to himself at the time how shabby he must have looked to them.

He remembers the meeting vividly.

“He walked in, in full uniform and saluted. I acknowledged (the salute) and stood up.

“He put out his hand and asked: ‘You were flying the Spitfire?’ ”

Caulton said he was the pilot and Major Jabs simply said: “I was the other pilot”

As he gathered his thoughts Jabs spoke again.

“When is the invasion going to take place?” he asked (Their meeting took place two months before the D-Day landings and the Germans knew there was something in the air).

“Churchill hasn’t actually told me I’m afraid,” Caulton replied with a wry smile.

Jabs apologised for asking such a question and didn’t raise the matter again.

Caulton told the Luftwaffe officers they didn’t have a show in the war, and cheekily suggested they give up on the spot.

“You can’t possibly win” he told them.

Twenty-five years later, in a letter from Jabs to Caulton, Jabs said: “You were right” about how the war was going for Germany.

Outside the hut the pair talked, and Caulton suggested that when hostilities were over they might even meet again.

Jabs took a piece of paper, and in large black lettering wrote on it “Major Jabs”.

He wrote that the bearer was to be allowed to keep “this souvenir of Major Jabs” and signed it.

Caulton still has the crinkled, somewhat faded souvenir today.

Meanwhile, German troops and other Luftwaffe officers scoured the crumpled Spitfire for their own souvenirs of the British fighter aircraft that even they held in great awe.

The aircraft was later destroyed.

Caulton was relaxed with the Luftwaffe officers who spoke quietly with him.

Despite being on different sides, and despite the “enemy” status each held toward the other, there was a common bond between them – the camaraderie of young men who respected each other’s roles and regarded each other as worthy opponents in the air.

However, Caulton wasn’t thrilled at the sight of the field security officers who arrived to take him away from the relative security of Major Jabs and his crew.

“They were the typical Hollywood image of German soldiers . . . cruel looking types who hardly ever spoke.”

He was taken away and sent off to spend an uncomfortable night in a cell in Amsterdam.

In Caulton’s mind, at that point, it was the last time he would meet the gentlemanly major who had shot him from the sky – but fate wasn’t about to see things that way.

The note, hastily and sincerely scribbled by Major Jabs, would eventually lead to reuniting the pair decades later.

But thoughts of reunions and forging new friendships were a long way from Caulton’s mind as he languished in the cold cell.

Food was basic … thin gruel stew from a pot heavy with the unwashed layers of previous meals. German bread, with imitation jam, was also provided. Asked today how it tasted, a look that mingles disgust and amusement crosses Caulton’s face.

He was transported across Europe back into Germany at a time when heavy allied bomber raids were being unleashed on the country.

The attrition rate for United States Air Force bombers carrying out raids was about 20 to 30 aircraft at a time, and he came across many American airmen, also prisoners and on their way to POW camps.

“At that time they were coming down like confetti.” he recalls.

Other images of being inside enemy lines and in an increasingly devastated landscape come back to Caulton.

He remembers being herded into a rail boxcar which had a sign hung from its side. It read: “Six horses or 40 men”.

He spent 3½ months in a POW hospital, just inside what is now East Germany, as he recovered from knee injuries received when he crashed the Spitfire.

His internment lasted exactly a year give or take two hours.

“I was shot down at 3pm on April 29 and we were free at 1pm, April 29 a year later,” he says.

He and 80,000 other prisoners at Mooseburg camp, near Munich, knew weeks before they were released that Patton’s army was closing in.

The Germans knew it too and began leaving the camp to defend against the approaching allied forces.

Free, Caulton travelled to Paris, for a riotous celebratory few days, before returning to Croydon, England, where he married his English bride Marie.

Apart from some brief post-war stints in Spitfires and Tempests, the war – the great adventure where John Caulton made and lost friends – was over.

But he still had a friend to make, a friend who, on the other side of the world, wondered about the New Zealand flyer he shot down.

In the early 1960s Caulton picked up and, read a book about the famous Battle of Britain.

Among the excerpts of stories was a piece written by a Luftwaffe air ace called Hans Joachim Jabs.

“I realised then he was still alive … it was a strange feeling,” Caulton said.

The opportunity to make contact with the man who ended his war came in 1968, when his daughter Jill went for a holiday to Europe after completing nursing training in New Zealand.

It was a long-shot.

Finding a man with a fairly common name in the heavily populated country of Germany was a tall order … more so considering Jill had a limited time of stay in West Germany.

However, Caulton’s brother-in-law, an officer with the RAF Security in London, came to the rescue.

He made inquiries to his counterpart at the West Germany Embassy and yes, they knew of Hans Joachim Jabs.

Many people knew of Jabs. He was an air-ace of reknown, but also a successful industrialist having built up a firm specialising in farm equipment.

The West German Embassy was at first reluctant to pass on details of Jab’s whereabouts … especially to a man on the receiving end of his wartime ME110’s cannons.

However, intentions were honestly established and the link was finally made.

Caulton wrote and Jabs replied.

In his first letter he expressed delight at hearing from Caulton, and told him of his own fate during the last days of the war.

In his faltering English Jabs said: “The year of 1945 was naturally full of very, very hard fights which I passed safe and sound”.

He was, however, made a prisoner of war himself, along with his fellow pilots and crew in the Luftwaffe night squadron, and was released late 1945.

When the pair finally met in 1972 during a trip to Europe and Britain, Caulton remembers saying simply that the event was “amazing”.

He can’t recall what was said but the friendship was genuine.

“It turned out to be a liquid occasion,” Caulton fondly remembers.

Old times were relived, memories rekindled, and the two men became firm friends.

In 1975 Caulton and his wife Marie made a second trip to Europe, this time visiting the area where as a 24 year old about 31 years earlier, he crashed his Spitfire into the farm paddocks of rural Arnhem in Holland.

He recognised the area, although the hut he was taken to had disappeared.

And he met up with another face from the past.

The Dutch farm worker who helped him from the wrecked aircraft still lived there, and the two enjoyed a remarkable reunion.

Since that first meeting in 1972, both Caulton and Jabs have met regularly – the last visit was by Caulton to Europe last year.

Sadly, plans for Jabs to travel to New Zealand (for the first time) may have been scuttled by the tragic death of one of his sons, who had been running Jabs’ Lister manufacturing firm since his retirement.

Jabs may have to turn his back on a welcome retirement to run the firm.

Apart from memories, the two have exchanged memorabilia from their wartime pasts, and the deep respect they formed for each other, as pilots and gentlemen back in 1944, has grown steadily stronger.

They are friends from different sides of the world. Friends who met under the clouds of a world war, in the colours of opponents.

They are two men who forged a unique friendship after one violent afternoon in the skies over Holland, 45 years ago.

Photo captions –

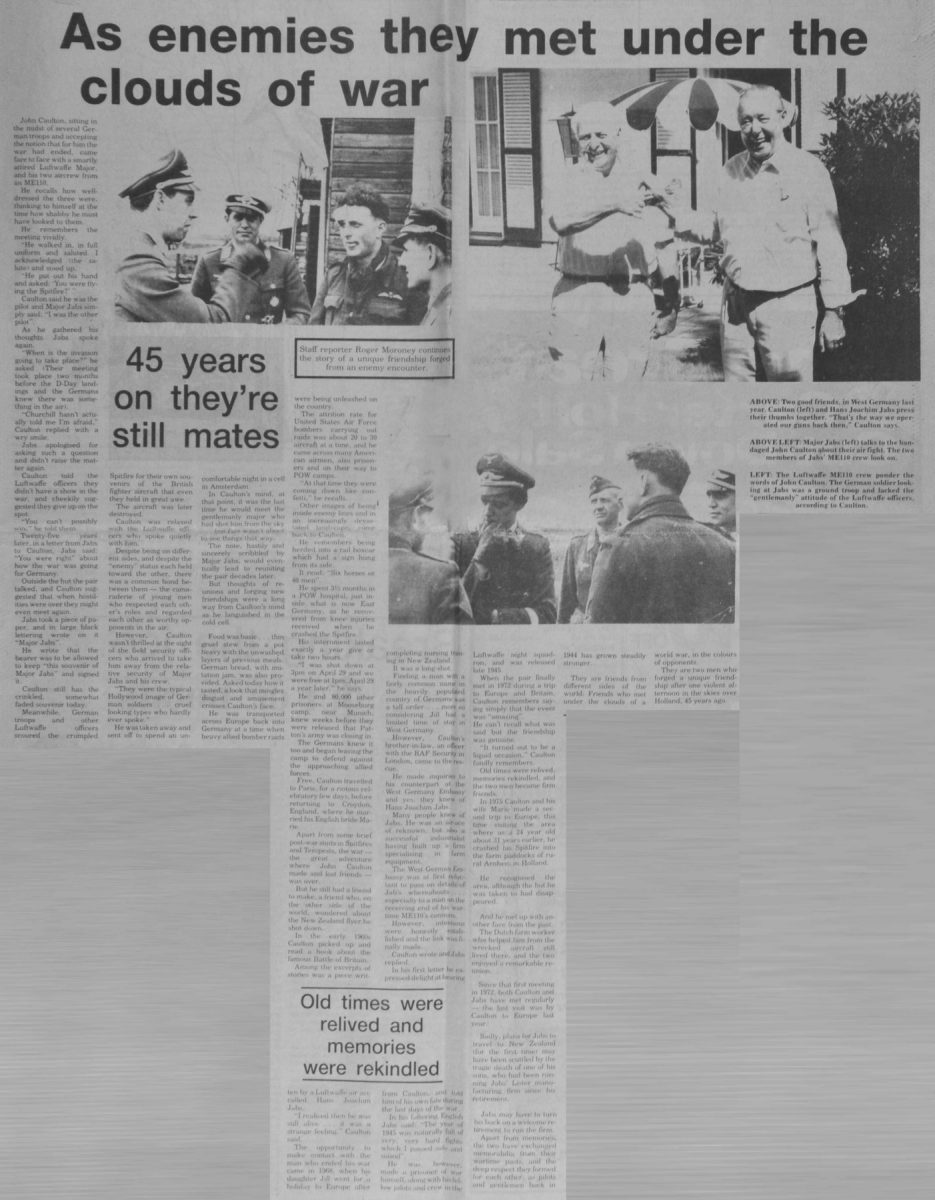

ABOVE: Two good friends, in West Germany last year. Caulton (left) and Hans Joachim Jabs press their thumbs together. “That’s the way we operated our guns back then,” Caulton says.

ABOVE LEFT: Major Jabs (left) talks to the bandaged John Caulton about their air flight. The two members of Jabs’ ME110 crew look on.

LEFT: The Luftwaffe ME110 crew ponder the words of John Caulton. The German soldier looking at Jabs was a ground troop and lacked the “gentlemanly” attitude of Luftwaffe officers, according to Caulton.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.