Shearing changed Maori lifestyle

1990: Past perspectives

By Hawke’s Bay historian Patrick Parsons

Sheep flocks increased rapidly in Hawke’s Bay in the 1870s and 1880s. Annual shearing requirements created a demand for reliable shearing services and thus the shearing gang came into being. While shearing offered the Maori population employment, it also affected the traditional way of life.

Shearers had to follow the work during the shearing season which meant either leaving or uprooting the family, living in comfortless shearers’ quarters and moving on to the next property when the shed was completed. Some gangs moved as far away as the South Island, married and established permanent roots there.

On the subject of shearing gangs, one person who speaks with the authority of more than 40 years’ experience is Tuhi Wilson, the grand old lady of Te Hauke.

Nearing her 90th birthday, in defiance of the hard-working life she has led, Tuhi is living testimony to the loyalty that often sprang up between station owner and shearing gang. She is the senior surviving member of the Edwards’ family whose shearing gang served the Williams’ family of Te Aute for more than 80 years.

The association between the Williams and the Edwards’ families began with Wiremu Edwards of Patangata. He shore for the Williams family in the late 1800s. When one considers that the Williams properties included Te Aute, Drumpeel, Penlee, Pukekura, Mangakuri, Clareinch and Waipari it becomes apparent that shearing for them was a whole season’s work.

Tuhi Wilson’s mother Tahuri was first cousin to Wire Edwards and worked in his gang. This was before the days of shearing contracts. Wire kept the times and a pay clerk employed by the Williams’ would ride out to wherever they were on pushbike and pay them, together with the shepherds and farmhands.

Tahuri in charge

When Wire Edwards retired, Tahuri and her husband Ihaka Nepia took over the shearing gang. She was a logical choice to carry on the gang. She knew the ropes and the Williams’s respected her ability to get things done. There was work for them in the off-season too.

Ihaka Nepia was put in charge of the Papanui cut, an ambitious project to drain the Roto a Tara swamp. A cabin camp was set up below Kahotea and supplies were taken out to the workers from Te Aute.

While the family was based at Te Aute, Tuhi caught the train to Opapa then walked back to the school just past the Te Aute pub. Getting home wasn’t so easy. There was no train service in the afternoon and the young Tuhi faced the long walk up Te Aute cutting to her home at Pukehou. Understandably her attendance tapered off.

“Mr Arthur Williams noticed my absence at Sunday school and made inquiries. He told my mother it wasn’t good, that I should go to school. He decided that he would enrol me at Hukarere. Mum only had to pay for my clothing. Hawke’s Bay girls never paid board. Outsiders paid ten pounds a year. The Maori gave the land for Te Aute College and our food was supplied from there so local girls got free board.”

At first Tuhi suffered badly from home-sickness. “My mother had to come and see me every month without fail. She’d come on a Saturday and we’d go down town.”

When Tahuri and Ihaka took over the shearing gang, the pay clerk was abandoned in favour of a contract. Holding the Williams contract was a guarantee of regular work. Provided the gang worked well, the contract would continue indefinitely. If work standards slipped away, the shearers risked losing the shed.

Tuhi’s mother and stepfather held the Williams contract for 40 years. As soon as she finished school, she rejoined them.

“I left Hukarere in 1918. When I came back, Mum and the gang were shearing at Waipari. I went straight out there in a taxi from Otane. I was in the woolshed the next day. I’d started work! My mother worked 40 years for the Williamses. I and my husband Niania worked the next 40, 80 years altogether.”

The work was hard, the endless succession of sheep soul-destroying. When the shearers got sick of it, the local pub was an oasis between jobs. Getting the gang to the next job wasn’t always easy.

Family Feuds

Sometimes it caused families to fall out and station owners would mediate before things got too bad. It was in their interests too for harmony to be restored.

The summer shearing season lasted through October, November, December and part of January, depending on the weather. Then there was a break until May when the crutching began.

Tuhi Wilson’s gang had a traditional starting date.

“For the last eight or nine years we started on October 9. Wherever we went, we stayed in the shearer’s quarters. Our food requirements were built into the contract. The station provided the meat, sometimes free if we were doing a good job. They did their own milking too and provided us with a gallon of milk a day.”

An essential member of the gang was the cook. Tuhi recalls their cook fondly.

“I had one cook for ten or twelve years. That was Janie Hawkins. She and her husband eventually got a house at Whakatu, Janie joined us when the shearing season started. Her husband worked at Whakatu. He would come out to see Janie at the weekends. She was a good cook, very economical. Times were hard and you couldn’t get potatoes. She made up all sorts of things.”

Tuhi learned her trade in the sheds.

“I was a shed hand. When mum still ran the gang, we had a classer from Tikokino or Ongaonga. He taught me to class. Two of us would skirt the wool, roll it up and take it to him. I’d pull a piece out and class it. He’d have a look and tell me if I was right. Eventually he’d go away for a spell and leave me in charge.”

When her husband died in 1955, Tuhi carried on the gang for three years. She didn’t have much trouble getting workers. When the work got too much for her, she passed the contract to George Himona, a relative of her husband who had worked with them for 18 years.

“He was doubtful but I said: “If you’re careful, you can make quite a few bob out of it.’ He married a pakeha woman. She took it on with him and made a good job of it.”

Photo captions –

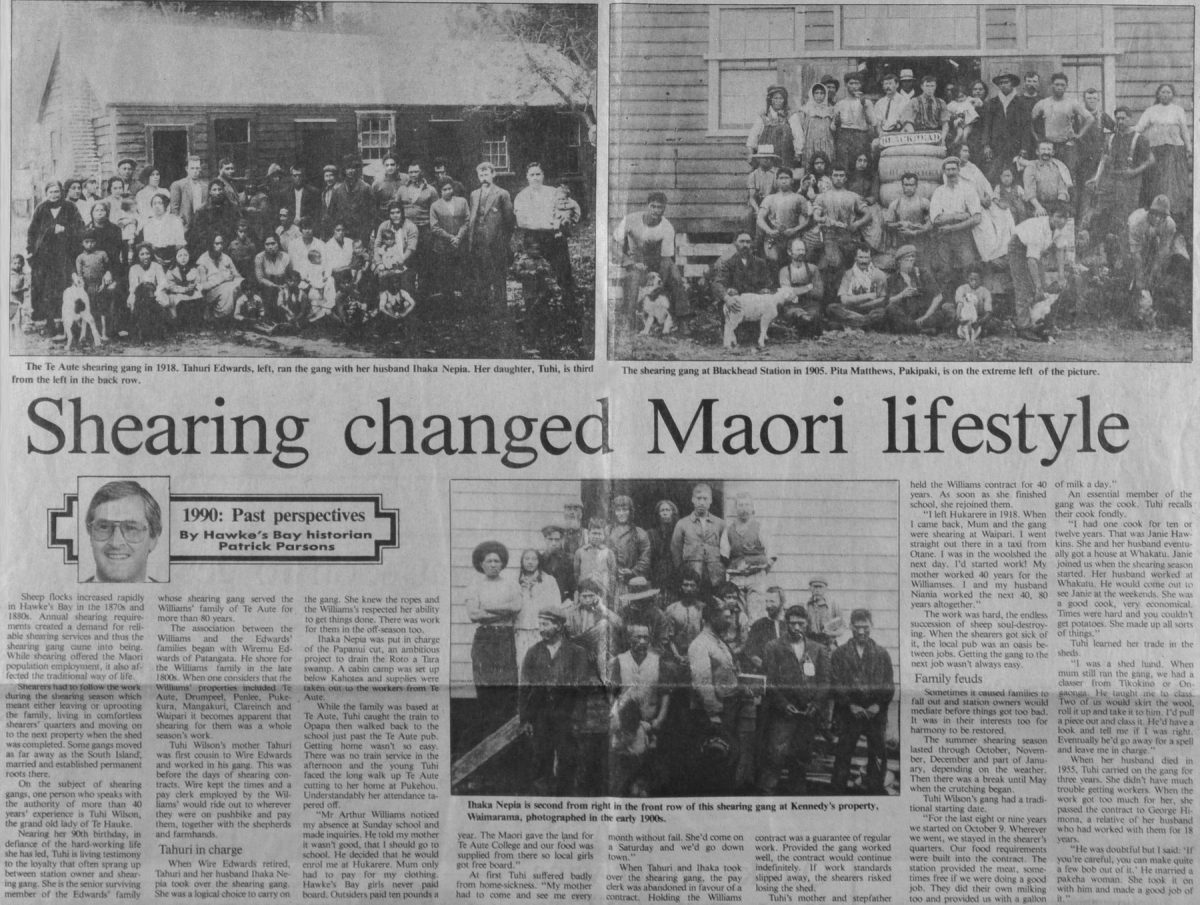

The Te Aute shearing gang in 1918. Tahuri Edwards, left, ran the gang with her husband Ihaka Nepia. Her daughter, Tuhi, is third from the left in the back row.

The shearing gang at Blackhead Station in 1905. Pita Matthews, Pakipaki, is on the extreme left of the picture.

Ihaka Nepia is second from the right in the front row of this shearing gang at Kennedy’s property, Waimarama, photographed in the early 1900s.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.