Hastings loved its caring nurses

The strong bond which existed between Hasting people and their hospital will be remembered by more than 220 nurses attending a reunion in Hastings this weekend.

One of them, Valerie Smith, who trained at the Hastings hospital between 1949 and 1952, has written a book The Charge of the White Brigade which is to be launched at the reunion. Her first book published in 1989 was For Better Or Nurse.

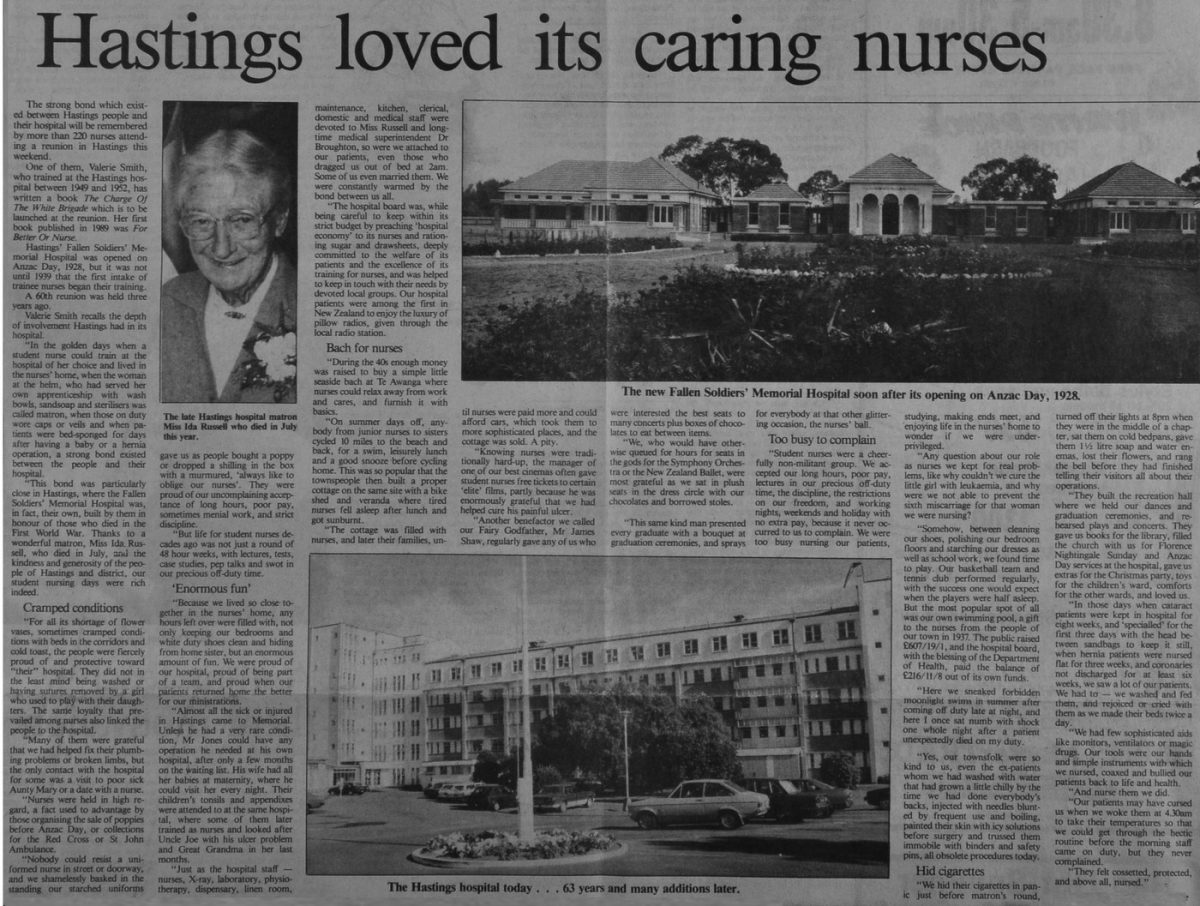

Hastings Fallen Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital was opened on Anzac Day, 1928, but it was not until 1939 that the first intake of trainee nurses began their training.

A sixtieth reunion was held three years ago.

Valerie Smith recalls the depth of involvement Hastings had in its hospital.

“In the golden days when a student nurse could train at the hospital of her choice and lived in the nurses’ home, when the woman at the helm, who had served her own apprenticeship with wash bowls, sandsoap and sterilisers was called matron, when those on duty wore caps or veils and when patients were bed-sponged for days after having a baby or a hernia operation, a strong bond existed between the people and their hospital.

“This bond was particularly close in Hastings, where the Fallen Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital was, in fact, their own, built by them in honour of those who died in the First World War. Thanks to a wonderful matron, Miss Ida Russell, who died in July, and the kindness and generosity of the people of Hastings and district, our student nursing days were rich indeed.

Cramped conditions

“For all its shortage of flower vases, sometimes cramped conditions with beds in the corridors and cold toast, the people were fiercely proud of and protective toward “their” hospital. They did not in the least mind being washed or having sutures removed by a girl who used to play with their daughters. The same loyalty that prevailed among nurses also linked the people to the hospital.

“Many of them were grateful that we had helped fix their plumbing problems or broken limbs, but the only contact with the hospital for some was a visit to poor sick Aunty Mary or a date with a nurse.

“Nurses were held in high regard, a fact used to advantage by those organising the sale of poppies before Anzac Day, or collections for the Red Cross or St John Ambulance.

“Nobody could resist a uniformed nurse in street or doorway, and we shamelessly basked in the standing our starched uniforms gave us as people bought a poppy or dropped a shilling in the box with a murmured, ‘always like to oblige our nurses’. They were proud of our uncomplaining acceptance of long hours, poor pay, sometimes menial work, and strict discipline.

“But life for student nurses decades ago was not just a round of forty-eight hour weeks, with lectures, tests, case studies, pep talks and swot in our precious off-duty time.

‘Enormous fun’

“Because we lived so close together in the nurses’ home, any hours left over were filled with, not only keeping our bedrooms and white duty shoes clean and hiding from home sister, but an enormous amount of fun. We were proud of our hospital, proud of being part of a team, and proud when our patients returned home the better for our ministrations.

“Almost all the sick or injured in Hastings came to Memorial. Unless he had a very rare condition, Mr Jones could have any operation he needed at his own hospital, after only a few months on the waiting list. His wife had all her babies at maternity, where he could visit her every night. Their children’s tonsils and appendixes were attended to at the same hospital, where some of them later trained as nurses and looked after Uncle Joe with his ulcer problem and Great Grandma in her last months.

“Just as the hospital staff – nurses, X-ray, laboratory, physiotherapy, dispensary, linen room, maintenance, kitchen, clerical, domestic and medical staff were devoted to Miss Russell and long time medical superintendent Dr Broughton, so were we attached to our patients, even those who dragged us out of bed at two a.m. Some of us even married them. We were constantly warmed by the bond between us all.

“The hospital board was, while being careful to keep within its strict budget by preaching ‘hospital economy’ to its nurses and rationing sugar and drawsheets, deeply committed to the welfare of its patients and the excellence of its patients and the excellence of its training for nurses, and was helped to keep in touch with their needs by devoted local groups. Our hospital patients were among the first in New Zealand to enjoy the luxury of pillow radios, given through the local radio station.

Bach for nurses

“During the forties enough money was raised to buy a simple little seaside bach at Te Awanga where nurses could relax away from work and cares, and furnish it with basics.

“On summer days off, anybody from junior nurses to sisters cycled ten miles to the beach and back, for a swim, leisurely lunch and a good snooze before cycling home. This was so popular that the townspeople then built a proper cottage on the same site with a bike shed and veranda where tired nurses fell asleep after lunch and got sunburnt.

“The cottage was filled with nurses, and later their families, until nurses were paid more and could afford cars, which took them to more sophisticated places, and the cottage was sold. A pity.

“Knowing nurses were traditionally hard-up, the manager of one of our best cinemas often gave student nurses free tickets to certain ‘elite’ films, partly because he was enormously grateful that we had helped cure his painful ulcer.

“Another benefactor we called our Fairy Godfather, Mr James Shaw, regularly gave any of us who were interested the best seats to many concerts plus boxes of chocolates to eat between items.

“We, who would have otherwise queued for hours for seats in the gods for the Symphony Orchestra or the New Zealand Ballet, were most grateful as we sat in plush seats in the dress circle with our chocolates and borrowed stoles.

“This same kind man presented every graduate with a bouquet at graduation ceremonies, and sprays for everybody at that other glittering occasion, the nurses’ ball.

Too busy to complain

“Student nurses were a cheerfully non-militant group. We accepted our long hours, poor pay, lectures in our precious off-duty time, the discipline, the restrictions on our freedom, and working nights, weekends and holiday with no extra pay, because it never occurred to us to complain. We were too busy nursing our patients, studying, making ends meet, and enjoying life in the nurses’ home to wonder if we were underprivileged.

“Any question about our role as nurses we kept for real problems, like why couldn’t we cure the little girl with leukaemia, and why were we not able to prevent the sixth miscarriage for that woman we were nursing?

“Somehow, between cleaning our shoes, polishing our bedroom floors and starching our dresses as well as school work, we found time to play. Our basketball team and tennis club performed regularly, with the success one would expect when the players were half asleep. But the most popular spot of all was our own swimming pool, a gift to the nurses from the people of our town in 1937. The public raised £607/19/1, and the hospital board, with the blessing of the Department of Health, paid the balance of £216/11/8 out of its own funds.

“Here we sneaked forbidden moonlight swims in summer after coming off duty late at night, and here I once sat numb with shock one whole night after a patient unexpectedly died on my duty.

“Yes, our townsfolk were so kind to us, even the ex-patients whom we had washed with water that had grown a little chilly by the time we had done everybody’s backs, injected with needles blunted by frequent use and boiling, painted their skin with icy solutions before surgery and trussed them immobile with binders and safety pins, all obsolete procedures today.

Hid cigarettes

“We hid their cigarettes in panic just before matron’s round, turned off their lights at eight p.m. when they were in the middle of a chapter, sat them on cold bedpans, gave them one and a half litre soap and water enemas, lost their flowers and rang the bell before they had finished telling their visitors all about their operations.

“They built the recreation hall where we held our dances and graduation ceremonies, and rehearsed plays and concerts. They gave us books for the library, filled the church with us for Florence Nightingale Sunday and Anzac Day services at the hospital, gave us extras for the Christmas party, toys for the children’s ward, comforts for the other wards, and loved us.

“In those days when cataract patients were kept in hospital for eight weeks, and ‘specialled’ for the first three days with the head between sandbags to keep it still, when hernia patients were nursed flat for three weeks, and coronaries not discharged for at least six weeks, we saw a lot of our patients. We had to – we washed and fed them, and rejoiced or cried with them as we made their beds twice a day.

“We had few sophisticated aids like monitors, ventilators or magic drugs. Our tools were our hands and simple instruments with which we nursed, coaxed and bullied our patients back to life and health.

“And nurse we did.

“Our patients may have cursed us when we woke them at four thirty a.m. to take their temperatures so that we could get through the hectic routine before the morning staff came on duty, but they never complained.

“They felt cossetted, protected, and above all, nursed.

Photo captions –

The late Hastings hospital matron Miss Ida Russell who died in July this year.

The new Fallen Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital soon after its opening on Anzac Day, 1928.

The Hastings hospital today … sixty three years and many additions later.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.