Havelock’s hills are steeped in Maori lore

The cultural significance of the Havelock North hills to Maori could play a critical role in the outcome of the debate over subdivision plans for housing in the Te Mata Peak area. Mike Tod reports.

A century ago the hills around Havelock North were occupied by Maori in a community stretching to Mt Erin.

This could be a crucial element in the fight to stop subdivisions. It will surface in appeals and deliberations on whether to implement a heritage order or a Treaty of Waitangi provision.

There are dozens of visible examples of Maori habitation, including pa sites and pits. Maori believe some of their sacred sites have already been disturbed by bulldozers.

Sites with significance to Maori have been recorded on the Joll land at the end of Durham Drive and on the McHardy block at the end of Hikanui Drive.

The Historic Places Trust has warned the law could be broken if sites are damaged. It is considering a request to implement provisions that would stop all development on the hills.

The penalty for intentionally destroying an archaeological site is conviction and a fine of up to $100,000. Malicious damage of a site brings a fine of up to $40,000.

Refusing an authorised person access for inspection can result in a fine up to $2500.

The burning question is: What is a place of spiritual significance to Maori?

The Maori and European view of this does not always seem to equate.

Europeans need specifics on where and when an event happened. Maori build their belief on identifying with an area through ancestral and occupational links.

In terms of Te Mata Peak and its legend of the giant, Maori give equal emphasis to all features and not just one spot.

The history of the Havelock hills will never be totally clear because the land was purchased by the Government before the Maori Land Act was passed in 1865. The Act required records be kept of land transactions involving Maori. Much of its aim was to stop chiefs selling land and dispossessing their people.

Kaumatua Jerry Hapuku said he felt an order must be put in place to protect all the land from the hill to Mt Erin. There were at least 50 known sites sacred to Maori.

Mr Hapuku said there could be hundreds more. An accurate figure could only be obtained after extensive archaeological surveys.

Maori have many reasons to back up their claim the hills are of high cultural significance.

From generation-to-generation stories have been handed down about events, battles and the way life was. These play an important part in Maori beliefs and culture.

A walk over the hills will show various sites of importance to them, including pas and pits.

The fact we know of the sites and stories can be attributed to the relationship between some of the early settlers and Maori elders of the time.

Sid Joll recorded in his notebook that around 1820 the Waikato Maori invaded the area and the Ngati Pare tribe, which lived along the range as far as Mt Erin, made its last stand at Pakake on the western spurs of Te Mata Peak. The locals were nearly exterminated and the few women and children who were spared went to the top and held a tangi, looking toward Cape Kidnappers and cutting their faces and bodies with sharp flints (mata). They were then taken to Waikato.

The lament sung by one of the leading women captured as she said farewell to Heretaunga from Te Mata Peak was well known by elders as a tangi chant.

Mr Joll noted there were extensive whare sites on the spur running up from the end of Durham Drive on the Joll property. The late Paraire Tomoana stated that a valuable mere was lost or hidden in the locality during the battle with the Waikatos. It has never been recovered.

The Havelock hills are the home of several burial sites because of the fierce battles over the centuries. The enemy did not take their dead back with them.

Nobby Gully below the Redwoods on the west is a well documented burial site. Some of the dead were placed in caves that were sealed.

During the past century some burial sites have exposed skeletal remains, which have been taken to Pakipaki to be buried again.

Mr Hapuku said the remains of some chiefs and their treasures lie in the steep cliffs. Access to caves and large cracks was gained by cutting steps into the cliff. On the way down the steps were removed to hide any trace of burial and treasures.

A section of the lower hills was once the home of a Maori woman battling tuberculosis.

Hiraani Te Hei married a European around 1900, but because of the disease could not have children. When she realised her life was nearing an end, she expressed a wish to adopt five or six-year-old Kathleen Blake.

Kathleen’s father was a Maori Land Court interpreter, and possibly with an eye to the future for his daughter, arranged the adoption.

To help cope with the tuberculosis Hiraani made a tent settlement near Hereworth School in an effort to be in the fresh air. As much as she wanted Kathleen to stay with her, the natural parents would not give permission for fear their daughter would get the disease.

However, she was allowed to visit.

Hiraani died around 1904 aged 28. Kathleen was a beneficiary and later married Charles Scott. She died in 1992 aged 96. She was the mother of the late architect John Scott.

In the early 1850s, a 1619-hectare native reserve, which incorporated a large area of the Te Mata hills was created. It was given the name Karanema’s Reserve, after a son of the chief Te Hapuku.

The deed of sale said: “This land is for the descendants of Te Heipora forever.”

Te Heipora was the wife of chief Te Hapuku.

Karanema died in 1854 during a measles epidemic and in 1858 the rectangular reserve became the site of Havelock North, legally acquired by the Hawke’s Bay Provincial Government for the sum of £800.

Mr Hapuku, a direct descendant of Te Hapuku, said Karanema had a pa on the Havelock hills. It was razed after he died to rid the area of the disease.

The pa was called Kahurangi, but its exact location is not known.

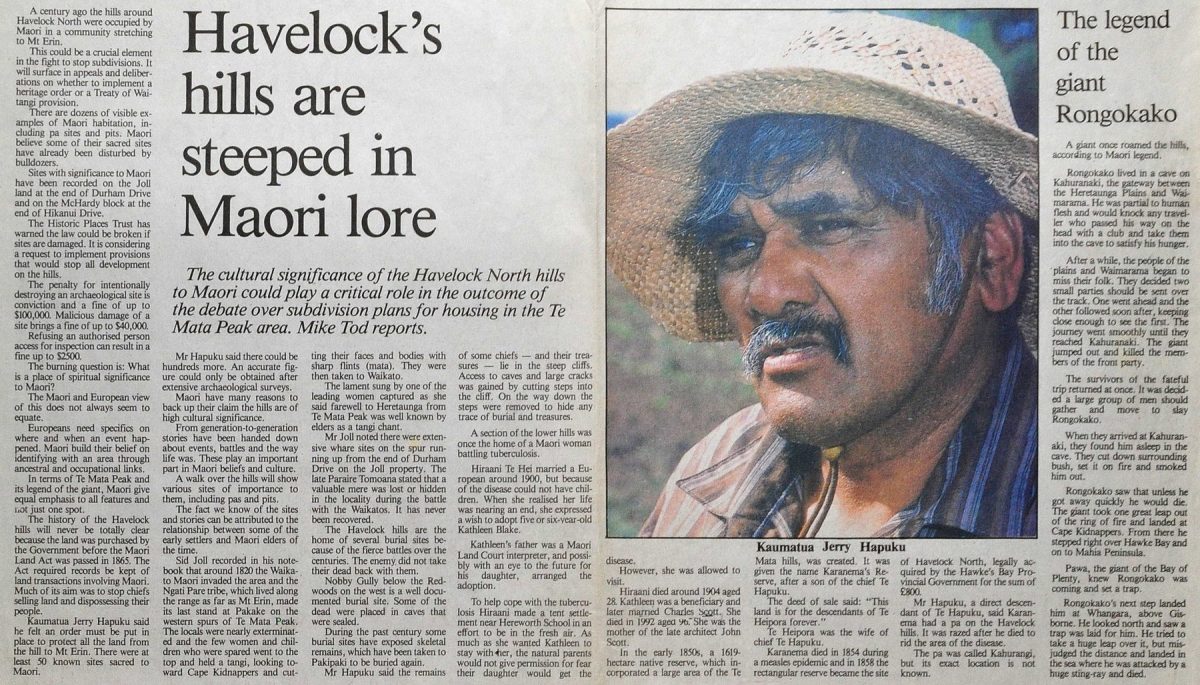

Photo caption – Kaumatua Jerry Hapuku

The legend of the giant Rongokako

A giant once roamed the hills, according to Maori legend.

Rongokako lived in a cave on Kahuranaki, the gateway between the Heretaunga Plains and Waimarama. He was partial to human flesh and would knock any traveller who passed his way on the head with a club and take them into the cave to satisfy his hunger.

After a while, the people of the plains and Waimarama began to miss their folk. They decided two small parties should be sent over the track. One went ahead and the other followed soon after, keeping close enough to see the first. The journey went smoothly until they reached Kahuranaki. The giant jumped out and killed the members of the front party.

The survivors of the fateful trip returned at once. It was decided a large group of men should gather and move to slay Rongokako.

When they arrived at Kahuranaki, they found him asleep in the cave. They cut down surrounding bush, set it on fire and smoked him out.

Rongokako saw that unless he got away quickly he would die. The giant took one great leap out of the ring of fire and landed at Cape Kidnappers. From there he stepped right over Hawke’s Bay and on to Mahia Peninsula.

Pawa, the giant of the Bay of Plenty, knew Rongokako was coming and set a trap.

Rongokako’s next step landed him at Whangara, above Gisborne. He looked north and saw a trap was laid for him. He tried to take a huge leap over it, but misjudged the distance and landed in the sea where he was attacked by a huge sting-ray and died.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.