Hawke’s Bay chief early Maori writer

RENATA’S JOURNEY, edited by Helen Hogan; Canterbury University Press; 175 pages; $29.95.

Renata’s Journey, probably the earliest piece of writing by a Maori, is of special interest in recording how the two races got on with each other in the first years of colonisation.

It is of special interest in Hawke’s Bay because Renata Kawepo, born near Hastings, became a powerful chief with an influence in the developing province. He played a leading role in the establishment of Te Aute College. When he died in 1888, 6000 attended his tangi.

The journey, in which Renata was guide and interpreter, was made by Bishop Augustus Selwyn in 1843-44 to visit missionary posts throughout the North Island.

The five-month journey was difficult and punishing. Tracks were notional, the bush thick, there were no bridges, and food was scarce. The journey was possible only because of the generosity, strength and skill of the Maori group which accompanied the bishop.

The dependence of the Europeans on the Maori was almost total. They would never have found their way through the bush, obtained food, crossed rivers or managed to struggle through difficult terrain with the Maori.

Many accounts of such journeys through pakeha eyes have been published. This is the first time a Maori view has seen print.

Near Hastings

Renata Kawepo was born about 1808 at Taumata, 20km west of Hastings. He was given the name Tama ki Hikurangi. Both his parents belonged to sections of the Ngati Kahungunu.

When Renata was a child his father died in battle.

His childhood was lived in troubled times. The Ngati Kahungunu were at war among themselves and were under attack from other tribes. About 1827, Renata a 17-year-old warrior, was taken prisoner at Te Hauke by the invading Nga Puhi. His name change is said to date from here.

Renata spent 10 years in the south with his captors as a slave, then was taken to the Bay of Islands in 1837. He was freed when his masters were converted to Christianity.

He quickly learnt to write English, and instructed missionaries in Maori. He was also able to draw moko terns for the missionaries’ instruction. He was no whimp, it seems. The missionary William Colenso described Renata as bumptious, and he was said to be large, and a champion wrestler.

Not understood

A parallel account of the journey by one of the Europeans, William Cotton, chaplain to the bishop, gives insight into how Europeans at that time were prone to misunderstand and misread the Maori.

Colenso was no exception. After the journey, Kawepo accompanied Colenso to establish a mission station near Clive. Colenso is recorded as saying that he took Renata Kawepo as a house servant. He seemed to be unaware of the fact that his “servant” was a high-born Maori returning to his Hawke’s Bay people as a teacher and leader. In fact, Kawepo made Colenso’s work much easier, and undertook some arduous missionary journeys.

The journey with Bishop Selwyn must rate as one of the most arduous expeditions ever undertaken in New Zealand, yet it is described in a matter of-fact way by Kawepo. Most mornings they were up between 4 and 5, and often did not stop until midnight. It seems that Maori mostly willingly lent canoes and provided food. One pakeha at a river crossing, however, would not allow the use of his canoe until two shillings were paid. Some Maori, too, were beginning to adopt the user-pays philosophy.

It seems that the pakeha slept in tents erected by the Maori, had their beds prepared for them, and had the best of what food was available. It also seems that they carried nothing. Everything was carried by the Maori party. At times, the Maori would cross streams with their heads under water but with arms holding their bundles high.

Insight

The whole account is an interesting piece of early New Zealand history, giving at the same time some insight into how the two races regarded each other and how each adapted to a changed way of life. Author Helen Hogan provides an important analysis of the relationship as seen in the two accounts of the journey. Renata’s account is printed in Maori as well as English.

In later years, Renata Kawepo quarrelled with the inflexible, autocratic Colenso and left the Hawke’s Bay mission in 1850.

Kawepo’s position as a chief continued to grow. By 1860, he had encouraged his Ngati te Upokoiri people to return and settled them at Omahu and Ohiti.

He argued against land sales and was involved in a battle against Te Hapuku in 1857 over the question, He was wounded in this engagement. The fighting alarmed the settlers in Napier, and Kawepo wrote to calm them. He later supported the King movement, and led an army contingent against the Hauhau and fought Te Kooti. A monument at Omahu records his campaigns and the bravery shown by his men.

An interesting piece of research that adds something valuable to New Zealand social history.

Photo captions –

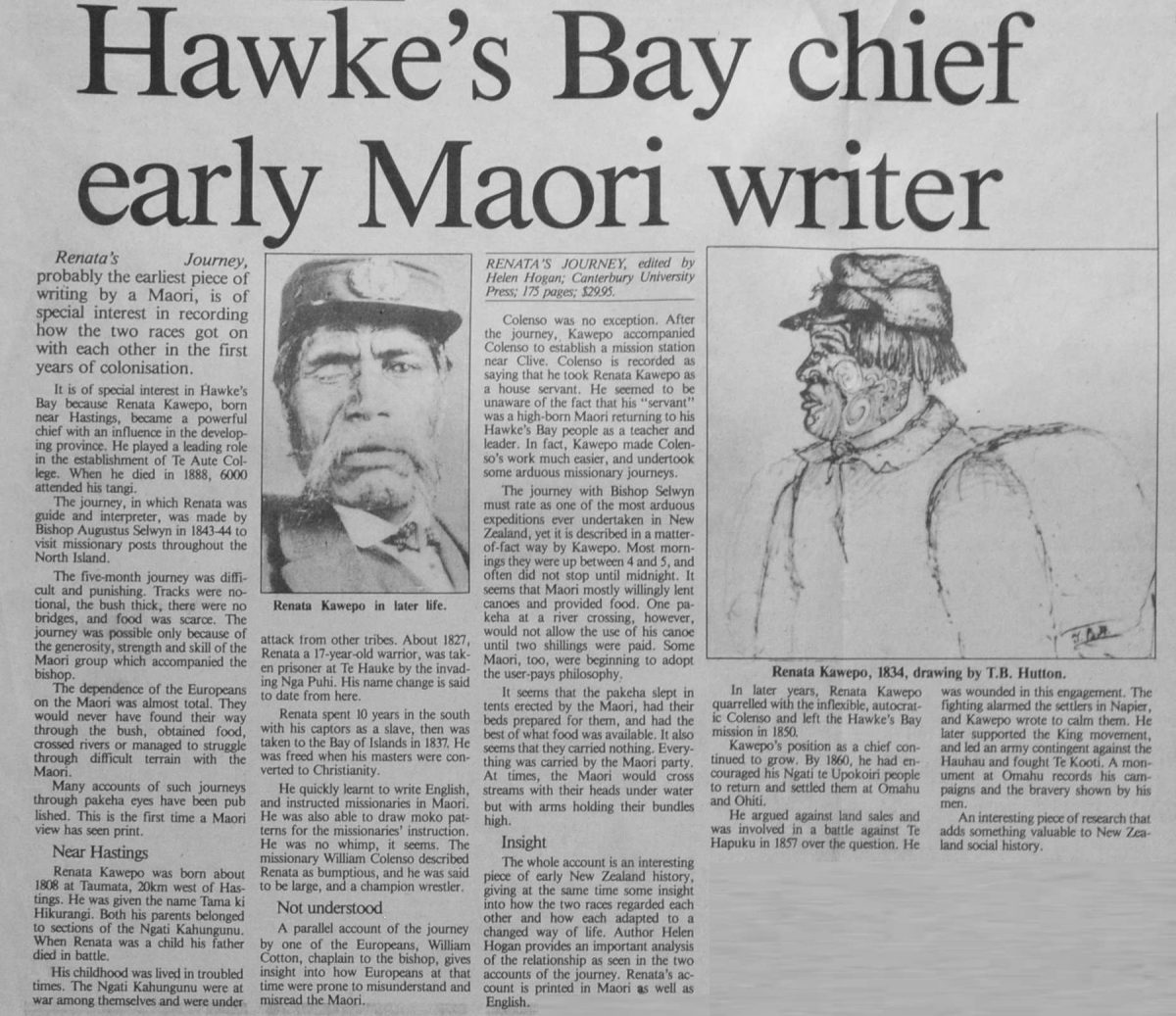

Renata Kawepo in later life.

Renata Kawepo, 1834, drawing by T.B. Hutton.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.