The way we were – the Parkvale class of 1944

On Friday Parkvale School, Hastings, will begin three days of celebration to mark the school’s 75th jubilee.

Here, a former pupil, Marye Trim, recalls the way her class of 1944 was.

In December 1944 I was in Standard Six and, with my peers, thought we had reached the very top, similar to, but not to be confused with Te Mata Peak where we sometimes hiked.

After all, we were the A and B basketball and football teams; we were the cream of the school from which came dux and scholarship winner. Oh, the dizzy heights of 1944!

It had not always been that way. In 1937 we started school as a motley lot of Depression kids, born after the great earthquake of February 3, 1931. Most of us flourished on the free school supply of apples and milk.

At home, many parents rejoiced in the change of government that had brought Michael Savage and the Labour Party to power in 1935. He was hailed as saviour of New Zealand and made my new school shoes possible. I remember his large photograph in kitchen and classrooms.

At school, Miss Bain ruled the infants room. Dark-haired, dark-eyed and an excellent teacher, we loved her, “A is for apple, B is for ball…” we used to chant, seated on the mat, watching her pointer: aiming to please.

On May 12, 1937, we stood to attention at the very front of the school assembly, listening to Mr Arthur, the headmaster and to the speech of the chairman of the school board.

Cheered the empire

They said that far over the sea, “at home in England” (an expression common to the predominantly British community), His Majesty King George VI and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth were being crowned in Westminster Abbey.

We applauded, we cheered the British Empire, we accepted small slices of celebratory fruit cake and a china mug with our Monarchs’ faces on it, and we sang “God Save the King”. The rest of the day was a holiday for which we cheered again.

The next year, 1938 – primers three and four in Miss Pickett’s room – asserted independence. “I think I’ll leave school now.” I could read and write well and manage pounds, shillings and pence; why stay? So, at six years, I quit.

Then I found myself enrolled at the Central School, a long walking distance from home in St Aubyn St east. I discovered my teacher there to be a wicked witch, and in comparison Parkvale was the Emerald City. So I quickly chose to return to my little school near Windsor Park, edged by paddocks, poplar trees and a country road.

In 1939, now taught by Miss Farram, we first tasted the pain of death when a loved classmate died, fair-haired Alison. We did not realise, then, that this experience pre-empted a feeling of loss which we would sense during the following years of war.

From 1939 – 1944, we were constantly aware that there was war waging, for our fathers, big brothers and uncles were all involved in some way at the home-front or overseas.

Food rationing

I remember yet those poignant pictures, in newspapers and magazines, of the latest war dead from Hawke’s Bay. Smiling brave faces, cut off from life too soon, they prophesied to us unimaginable pain in adulthood.

But we knew we must make do with butter and sugar rations, help to weave rope hammocks and raise money for the war effort. So our class resolutely collected a mountain of discarded Craven A cigarette packets as cardboard for fund-raising.

Of course the arrival of American servicemen in Hawke’s Bay reminded us that we were in a world war. This knowledge even pervaded our games for, as we played marbles on a dusty patch of playground, vying for a big glassy, we argued about which force was better – the American Marines or the New Zealand Army, Navy or Air Force. Completely bigoted, we also asserted our opinion of Germans and Japanese.

Time went by with a new headmaster, Mr Roe, and other teachers – Miss Emmerson, Miss Dent, Miss Hay, the latter two each taking us for two developmental, nurturing years.

We continued to play dentists in playground arbours covered with climbing roses; we had secrets and special clubs. Some of the girls started to develop busts and kept lists of how many times they had been kissed by boys. A classmate lent me a copy of True Confessions which rocketed my mother into an orbit of fury.

Tuck shop pies

We continued to buy meat pies for lunch from Mrs Bagley’s tuck shop when we could scrounge threepence from our mums. Those pies were hot and memorably packed with mince and gravy. Sometimes we bought mixed lollies at six for a penny.

Then finally, one December day we were the really big kids, the class of 1944 destined to move on to various high schools and colleges. We understood long division and decimals, appreciated the fish of Maui, the five great ocean-going Maori canoes and the Treaty of Waitangi. We knew if we preferred comics to Biggles, Ballet Shoes or the stories of Katherine Mansfield. We recognised Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland as essential screen viewing – at the State or Regent, preferably.

So we declared our ambitions – secretaries, hair-dressers, builders, chefs, bank managers, teachers, musicians, writers…mummies and daddies, of course.

Fifty years on, I salute the class of 1944, sometimes strapped for punishment but not holding grudges, for we loved our school. You are important to the jubilee memories of Parkvale and in the history of Hastings, Hake’s Bay, where our world began.

Photo captions –

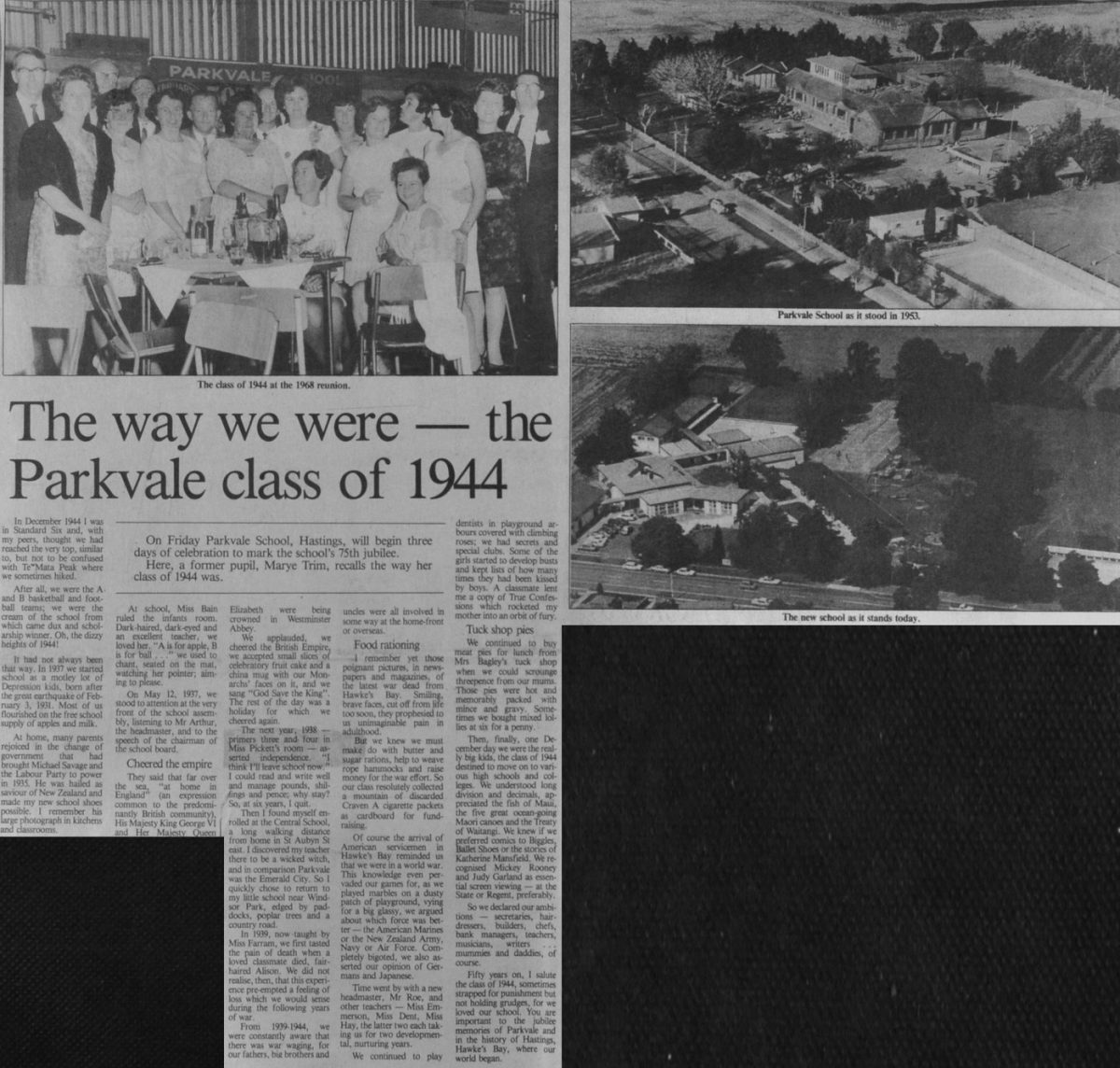

The class of 1944 at the 1968 reunion.

Parkvale School as it stood in 1953.

The new school as it stands today.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.