Herald-Tribune reporter Mary Shanahan, who won the Dublin-based Independent Newspapers’ inaugural fellowship enabling her to work on several of the O’Reilly group’s newspapers in Dublin for three months, decided to trace the roots of her ancestry while she was there…

THE IRISH famously enjoy a punt as much as a pint and the head of the National Library’s genealogical service in Dublin is not about to undermine his countrymen’s reputation.

Bernard Devaney makes me two bets, generously offering low stakes when I confess that diluted blood lines have weakened my gambling, genes. A penny that my great-grandparents did not marry in London, he says, and another that my great-grandfather was named Patrick rather than John.

Curious about how genealogy pieces together the past, I rise to the challenge – my family’s anecdotal history versus Bernard’s expertise. My search for evidence will start in the genealogical office of the handsome library building.

The Great Famine does not appear to have been the direct reason for my family’s emigration to New Zealand. With a brother, my great-grand-father John Shanahan is said to have left his hometown of Shanagolden, Limerick, 1872, bound for the goldfields of Victoria.

John’s wife Ellen and three sons stayed behind while the two brothers sailed for Australia and then moved on to the central Otago goldfields. After they had built a sod and shale cottage on what is now the Arrowtown Golf Club, Ellen and her young children joined them. My great grand-parents went on to have another three sons, including my grandfather Thomas.

But many of Irish descent who dig for roots do unearth blighted tubers. In the early 19th century, even the poorest Irish peasant leased land to grow potatoes to feed his family while other crops paid the rent

Between 1845 and 1849 the potato crops were devastated by disease introduced to Europe from North America. The failed harvests triggered widespread famine, a catastrophe which joined a chronology of Irish troubles.

An 1841 census recorded Ireland’s population at 8,177,744. Within 10 years it had dropped to 6,554,074 – an estimated million people had starved and the Irish diaspora had begun in earnest.

Throughout the country, communities held “wakes” as final farewells to those with the will and the wherewithal to sail on the so-called coffin ships to America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South America.

Emigration continued at a high level until the 1960s. Although the population is presently only 3.5-million, the booming Irish economy is attracting people and investment. Ironically, tracing ancestors is among the new growth industries, attracting tourists and employing genealogists. As the owner of a bed and breakfast jests, “Thank God for Irish emigration”.

Connie Martin of Dayton, Ohio, is in the library to track her mother’s family tree. With the unusual name of John Morten Gaffney, the ancestor who took his family to the US in the 1820s should be comparatively easy to track.

But like many who check in with the genealogical services, she has allowed little time for a search process that typically becomes increasingly complex and time-consuming. And she will find civil records don’t go back as far as she would like – many were destroyed in Ireland’s Civil War between 1921 and 1923.

The name of my great-grandfather is found in the Griffiths Valuation which recorded land leases from 1848 to 1864. Most searchers “fall off their chairs with surprise” when they meet with such early success. I’m going to be hard to impress, Bernard wryly remarks.

To scan through microfilm parish records held in the reading room upstairs needs the okay of the Limerick diocese, one of the three requiring written permission to search entries that are handwritten in Latin.

Luckily the priest who recorded baptisms in the Shanagolden parish had a legible hand – an American woman at the next desk gives up on the scrawl she has been checking.

Ghosts are sitting on my shoulder as I locate the entry for Patrick Shanahan, my great-uncle and the eldest of the sons born to John and Ellen. Although both parents were from Limerick, my late father said they married in Kensington in the 1860s. But Bernard considers it unlikely that they would have wed in London and then returned to their Irish homeland to lease farm-land. It was typical, he says, for the lease to be arranged before a wedding which would be celebrated in the wife’s parish.

The search moves to civil records in the nearby Public Offices where a long post-lunchtime queue waits outside. When I finally get to the search room, people are jockeying for single copies of yearly index books which record births, deaths and marriages.

Bad luck if you are looking for a common name like Murphy or Flynn – the indexes provide minimal information. Likely leads necessitate a fuller search costing more time and money. The hardpressed staff member is at full stretch following up with checks of more comprehensive records not available to the public.

Complicating my hunt, I eventually find Pat has been entered as Patt and his birth is recorded not under Shanagolden or Limerick but what turns out to be an administrative district called Glin.

His name is the reason Bernard has taken the second bet. Last century Irish children typically had a single Christian name. A first son was named after his paternal grandfather and. the second boy after his maternal grandfather. Will this make my great-great-grandfather another Pat/Patt/Patrick?

Cross-checking the all-Ireland marriage indexes, there is no entry for John Shanahan and Ellen Nolan. That wager is looking pretty safe.

The civil records don’t go back further than 1864 so the next step is to visit Shanagolden.

The briny air of the Shannon estuary wafts in the car window as I drive toward the village that was the family home until 1875. I try to suppress the rising sense of anticipation — what if the town turns out to be an ugly backwater? To my relief, Shanagolden is a charmingly honest hamlet cradled in rolling pastureland.

Having forewarned Father Tony O’Keefe, parish records are on hand and (glory be) they are in English, typed, in chronological order and under family names – the result of a work scheme project initiated by a Limerick lawyer interested in local history.

Although I’ve won one wager, I’m ready to concede to Bernard on the name bet. The first marriage recorded under the Shanahan list is on February 21, 1827, between Patrick and Hanora Shanahan who check out as the parents of John, James, Patrick, Thomas, Winifred and Maria, born between 1832 and 1857.

Father O’Keefe, perplexed by the number of Australians calling to check records, was referred to a newly published book, From Poverty to Promise, which tells the story behind the large number of Shanagolden emigrants to the smallest continent.

The lessor of farmland in the area, Lord Monteagle helped more than 730 men and women to leave on 66 ships for Victoria and Sydney in a migration chain that began in 1838 and continued until 1858.

Shanahans are included in passenger lists and I’m confident John and his brother would have had relations in Australia when they set off on their trip to the other side of the world. No- evidence of family members can be found in cemeteries on either side of the town. But many graves are unmarked and time and lichen have eroded inscriptions etched in stone.

In Cork, the railway station at Cobh harbour where Irish immigrants arrived to board ships has been turned into a maritime museum documenting the diaspora. This is where John and Ellen would have finally farewelled Ireland.

Tracking down the jigsaw pieces that are family history has proved a largely rewarding search. The hunt could be pursued with checks of Shanahans on Australian and New Zealand immigration lists so that the family tree could look as leggy as a millipede.

But threaded in with other emotions is the soft sadness of knowing genealogy can only ever shine the dimmest of lights on past lives. How Irish migrants steeled themselves to leaving their homeland and parents, risked typhoid and capsize on the dreaded coffin ships and settled in foreign lands – that’s the bigger story which only the imagination can flesh out.

Photo captions –

A quiet village between arterial roads, Shannagolden is no longer home to any Shanahans.

A Gaelic welcome to Shanagolden.

Failce go Seanaghualainn

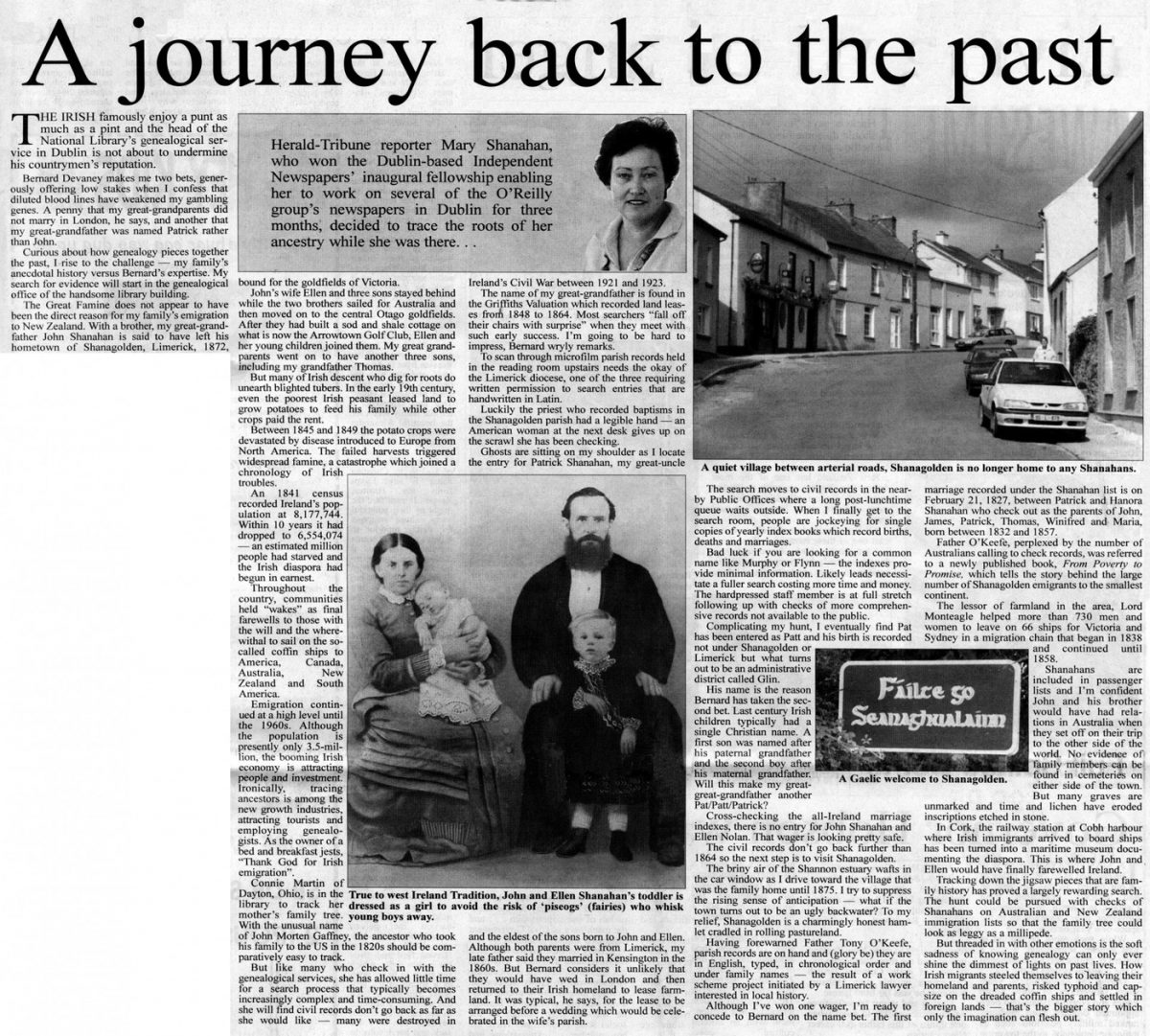

True to west Ireland Tradition, John and Ellen Shanahan’s toddler is dressed as a girl to avoid the risk of ‘piseogs’ (fairies) who whisk young boys away.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.