It will be exactly 50 years tomorrow that people like Napier’s Saima Pritchard (then Saima Antje) began a new life. She was one of hundreds of “displaced persons” who arrived in Wellington aboard the Dundalk Bay on June 27, 1949, as there was no longer a home for them in Europe. She was born in Estonia but has not seen the beloved land of her childhood since she and her mother were forced to leave in 1944. She is one of a number of Estonians now living in Hawke’s Bay.

ROGER MORONEY spoke to Saima. This is …

SAIMA’S story

They have been on the television news almost every night since it all went tragically mad in the Balkans.

Refugees, laden with what little they could gather up, apparently walking nowhere away from what was once their home. Their plight has introduced new words for misery and suffering into the English language. Words such as Kosovo and Pristina.

And while their faces are unfamiliar, the expressions they wear are enough to bridge five decades for Saima Pritchard.

When she sees the refugees, particularly those embarking on a new life somewhere on the other side of the world, the memories return.

Memories of a war which began 60 years ago and which saw her beloved Estonia, a small Baltic nation bordering the former Soviet Union, become the target of aggressors.

She can read the expressions of the Kosovo refugees. She can pretty much understand what they are feeling, and has some simple advice.

“If they are going to stay in New Zealand and think it will be a better place for them and their children, then I say open your minds and open your hearts. Accept what you find here. Go slowly. Take what you need and give what you can.”

In her own situation, when she arrived in Wellington to the terrifying sight of huge hills and distant mountains (“we all wondered how we were going to get across them”) she was determined to “get on with it”.

She and her mother, like thousands of other Estonians, along with Czechs, Poles, Latvians and Lithuanians, had little choice but to leave the lands they called home. Before embarking on a scruffy converted troopship to New Zealand in 1949 they spent five years wandering Europe as DPs (displaced persons).

Her parents had separated by then. Her father, a tall, distinguished looking man, was an officer with the German-aligned Estonian SS, while her mother’s name had been placed on a death list by the Russians.

“She was to be shot. Her crime? She had been a registrar of the civil court.”

The chaos of war, fused with the political empire-building of greater powers, wrecked the small, dignified nation of Estonia – a homeland Saima last saw 55 years ago.

She is a strong-willed woman – something no doubt inspired by having to use her wits and guile to stay one step ahead of the Russians as she and her mother sought freedom. Yet while the years have helped her cope with what she experienced, her voice lowers and there is clear sadness in those eyes when she speaks of how everything changed.

Born in the capital, Tallinn, she was nine years old when the Russians marched into the country in 1939 in a brazen annexation which drew little response from nations the Estonians thought would have stepped in to help.

“The Russians, they thought they owned everything,” she said angrily, adding Estonia was helpless to resist as most of its small army was in Finland.

Ironically, they had gone there to bolster Finnish forces in the face of Russian movements.

“Our president called for help from what he thought were our friends, and that included England. But no-one wanted to know. Don’t talk to an Estonian about Churchill!

“When the Russians first came we all hoped nothing bad would happen,” Saima said. But eleven of our family were sent to Siberia. My uncle was the finance director of Estonian Railways. He had a wife and two young daughters. My uncle was never seen or heard from again.”

His wife, described by Saima as an immaculately presented woman, was not able to return to Estonia for 20 years.

“She was dilapidated, she was an old woman. She had been working, labouring. It was no life.”

Her mother’s stepsister and husband, and their four children and another relative were also sent away. None of the men was ever seen again.

At the time, because she was only a child, Saima was more bewildered than frightened, and even after the Germans took their turn to move into Estonia she was not afraid.

“As long as you weren’t Jewish they would leave you alone.”

However, as the years went by it became increasingly clear that there would be no future for her, and many hundreds of others, in Estonia.

As Germany’s war began to falter and its troops began moving out, the Russians showed every sign of moving back in. It had become too dangerous to stay.

Saima had to leave the land of her birth, able to take only the memories of wonderful childhood years when she visited her grandfather’s farm and walked the flat, green fields.

She laughed while remembering Estonia’s two “mountains”, the highest of which was just 300m, and recalled the heavy snowdrifts of winters where the temperature dropped to -20deg.

That was all left behind when, on the advice of her boss, a judge by the name of Mr Sulke, Saima’s mother made plans to get out.

“Grab your daughter and go quickly,” was his simple, desperate advice to Saima’s mother.

They found a place on a German cargo ship and left the port of Tallinn on August 22, 1944.

Saima was 14, and didn’t know at the time it would be her last glimpse of home.

“We were ever hopeful that one day we could go back.”

Her mother shared her optimism, and wrote in a diary of the departure:

“It was beautiful but terribly sad to watch the sun setting over the towers and steeples of Tallinn. When will I see you again my dear hometown, with all my dear ones?”

The voyage was uneventful despite the threat of Russian air attack, and a day later the ship anchored in Gotenhafen harbour (in former East Germany).

Saima and her mother were told they would have to wait aboard as the refugee camp they had been earmarked for was full.

But within hours an order was issued allowing people to go ashore to “wherever anybody wanted to go”.

The refugees scattered in all directions, with Saima and her mother taking the advice of Mr Sulke and his family and setting off for Plau, a small town about 120km west of Berlin. They spent the nights sleeping in railway stations before arriving in Plau on August 26.

Her mother wrote “for accommodation we were given straw mattresses and the floor of a closed barber’s shop”.

Two days later they moved on to Parchim, about 20km away, but were forced to return to Plau. Then they were sent back to Parchim again and spent an uncomfortable night before being moved to a refugee camp.

“There are Russians everywhere,” her mother noted.

“If they are going to stay in New Zealand and think it will be a better place for them and their children, then I say open your minds and open your hearts. Accept what you find here.”

Saima Pritchard

FORMER REFUGEE FROM ESTONIA

“Today suffering from homesickness. Weather is very bad. Impossible to go anywhere. We sleep in one room with at least 30 people. No privacy. Lumpy straw mattresses, no sheets, thin army blankets of dubious cleanliness. Food is army style. No dining rooms. Communal showers are cold. Men, women, children live all together. No privacy.”

Aware they were in constant danger, due to the death sentence the Russians had placed on her mother, the pair decided to assume Flemish identity and even took up speaking it.

“We hid behind the Flemish language,” Saima said.

Months went by and the war was essentially lost for Germany. With the allies pushing into the heart of Hitler’s empire, Saima and her mother targeted Hannover, about 160km to the southwest, as it was away from the Russian advance.

But getting there meant getting past the Russian line, and that meant possessing the right papers.

“You had to have papers for everything. The Russians knew all about lots of papers but they didn’t really know where anything was. You could lie to them.”

Aware of the danger her mother would be in if she was identified, Saima approached a border guard for the appropriate stamps and signatures to get to Hannover. First she got her own stamped, then went back later with her mother’s papers.

“I flirted with the Russian there. Oh how I flirted,” she laughed.

As she made small-talk with the delighted guard, she placed her bag over the top of the papers, hiding her mother’s name and details. Had the guard scanned the identification document properly he would have discovered teenage Saima was apparently a woman of 40-plus years.

But, smitten by the attractive girl in front of him (who promised to meet him in Hannover if he let her go there) he simply signed and stamped the papers.

Saima and her mother were on their way but still had to contend with large numbers of Russian troops on the roads.

“An American army jeep arrived and they started waving their arms about – as did the Russians. An American then came over and said ‘its okay now, we’ll watch over you’. We had a beautiful sleep that night.”

They spent five long years in camps, along with tens of thousands of displaced people, before being made aware New Zealand was taking refugees as “new settlers”.

There was nothing for them in a Europe battered by six years of war, and a homeland annexed by the Russians.

So they set sail, with about 950 other DPs, on the 7000-tonne Dundalk Bay, a former German troop carrier re-registered under an Irish flag, and arrived in Wellington on June 27, 1949.

It was a strange, peaceful new world and Saima determined to make the best of it. Her excellent education and good command of English saw her eventually find work in government departments after initial stints waitressing and working as a seamstress.

“I did not want to waste my education.”

But her mother, who died about 10 years ago without ever again seeing her beloved Estonia, never really settled.

Saima remembers well the early months of Kiwi-hood as she lived in a camp at Pahiatua.

“It was a thousand times better than what we had. The food was good and we had hot water.”

Her only concern, having been taught English as a girl by a teacher who had attended Oxford, was understanding English, Kiwi-style.

“What was a bloke? What was a sheila?” she laughed.

She moved to Napier in 1956 (the same year she was naturalised) on the advice of a doctor in Wellington concerned about her mother’s health.

“The doctor said Napier had a better climate so I got a transfer through the Lands and Survey, and here I am.”

She met Colin (“a very nice Kiwi man who has spoiled me rotten”) and married.

Sadly she lost a baby boy, but she and Colin raised two daughters. With pride she showed a photograph of them when they were little. They are wearing beautiful Estonian traditional costumes she made herself.

“I am a naturalised Kiwi and this is where I live, but I am a proud Estonian,” she said.

It is her wish that the displaced people of Kosovo, those tagged as refugees, will be like her and find a new home in New Zealand, work hard and “make all they can of it”.

Photo Captions

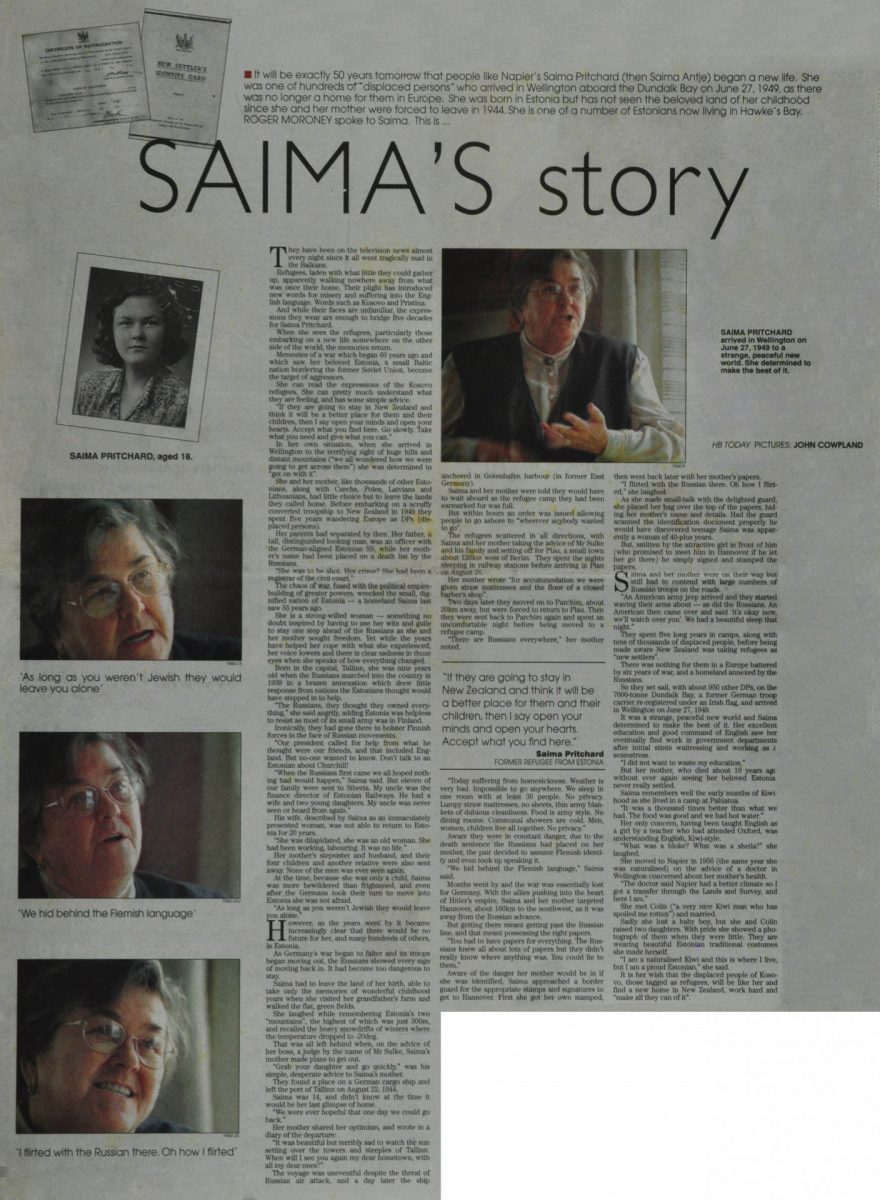

SAIMA PRITCHARD arrived in Wellington on June 27, 1949 to a strange, peaceful new world. She determined to make the best of it.

HB TODAY PICTURES: JOHN COWPLAND

SAIMA PRITCHARD, aged 18.

‘As long as you weren’t Jewish they would leave you alone’

‘We hid behind the Flemish language’

‘I flirted with the Russian there. Oh how I flirted’

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.