William Colenso – the botanist

The centenary of the death of William Colenso was marked by a ceremony organised by the Hawke’s Bay branch of the Royal Society at the site of the Mission Station at Waitangi, Awatoto.

Colenso was secretary-treasurer of the Hawke’s Bay Philosophical Institute, the former operator of the branch, for 10 years.

This article discusses one of the province’s most influential pioneer figures.

Interest in Colenso tends to centre less on his successes than on the qualities which animated his work.

Other men could have achieved success as printer, missionary or scientist, but could many have reached the same high levels in several fields and done so despite frustrations and disappointments such as were suffered by Colenso?

To see the man for what he was requires knowledge of his beginnings. Well educated in a private school and at the age of 15 began work with a Penzance, England, printer.

Six years later he was an efficient printer and bookbinder who used his spare time to visit the British Museum and the Zoological Gardens at Kew. He heard that the Church Missionary Society wanted a printer for New Zealand, and after applying was taken on.

After arriving he found many printing supplies had not arrived, but made do and in less than two months produced the first book in Maori on some of the scriptures.

His “History of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi“ was adopted as the official account. From around Paihia he collected specimens of shells and insects and his interest in natural history was encouraged.

In Paihia Colenso was to meet three scientists of note.

On Christmas Day 1835 he saw and heard botanist Charles Darwin. But of more importance was his short friendship with Allan Cunningham who he met in 1838.

The pair worked together and Cunningham collected botanical material for Colenso.

In the years before his death he encouraged the young printer-botanist and through him another contact was made in 1841. Colenso’s work had impressed Lady Jane Franklin. She and her husband, Sir John Franklin, Governor of Van Dieman’s Land, had done much for the encouragement of science in the Southern Hemisphere.

On her return to Tasmania from Paihia she sent Colenso a botanical microscope.

He was asked to contribute to the newly-founded “Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science,” to the controlling society of which he had been elected a corresponding member.

A still more important event was to occur in August 1841 when the brilliant young scientist, Joseph D Hooker, entered Colenso’s life. From then on natural history was to permeate Colenso’s existence.

He was not free to join Hooker as often as he wished, but often enough to learn much of plant hunting and to begin a life-long friendship. With increasing confidence Colenso sent specimens to Hooker. There were many qualities in Colenso which caused him to be accepted as a fellow traveller by the Maori, whom he described as ‘these friendly people’.

In less than 10 years he crossed the North Island by at least three routes. He walked its length using different routes and explored his mission district thoroughly.

In Hawke’s Bay, in 1845, on his route to reach parishioners dwelling in the inland Patea country, he travelled along the Waipawa and Makaroro rivers heading for the peak of

Te Atuaomahuru .

While that journey failed in its objective it was far from fruitless.

He wrote: “But when at last we emerged from the forest, and the tangled shrubbery on its outskirts, on to the open dell-like land just before we gained the summit, the lovely appearance of so many and varied beautiful and novel wild plants and flowers richly repaid me the toil of the journey and the ascent – for never before did I behold at one time in New Zealand such a profusion of Flora’s stores.

In one word, I was overwhelmed with astonishment, and stood looking with all my eyes, greedily devouring and drinking in the enchanting scene before me.

I had often seen what I had considered pleasing Botanical displays in many New Zealand forests and open valleys . . . but all were as nothing when compared with this – either for variety or quantity or novelty of flowers, – all, too, in sight at a single glance.

But how was I to carry off specimens of those precious prizes?

And had I time to gather them? I first pulled off my jacket, or small travelling coat, and made a bag of that, and then … I added thereto my shirt, and by tying the neck … got an excellent bag; while some specimens I also stowed into the crown of my hat … fortunately the day was an exceedingly fine one, calm and warm, so that I did not suffer from want of clothing.

That night I was wholly occupied with my darling specimens, putting hem [them] up, as well as I could … among my spare clothing, bedding, and books; only getting about two hours sleep towards morning.”

Rarely in existing records does one read of Colenso carried away by intense pleasure.

Apart from his dynamic interest in botany he was the first European to document the impact of forest destruction in the Ruahine Range in 1845 and 1847.

Colenso’s clarity of speech in describing his experiences leaves no doubt about the meaning.

One can easily picture Colenso and his friends either struggling over logs, or having crashed down through the rotten logs into a large, deep pit.

About 1867 Sir Joseph Hooker’s work “The Flora of New Zealand” was published. Colenso had the honour of being one of the principal contributors.

Hooker, the senior British botanist, paid tribute to his enthusiasm and devotion as a collector, saying: “In every respect Mr Colenso is the foremost New Zealand botanical explorer and the one to whom I am the most indebted for specimens and information.”

In 1867 the New Zealand Institute was formed in Wellington and Colenso was a foundation member.

He had prepared two papers for the Dunedin Exhibition and from this time Colenso was a constant contributor.

The Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Philosophical Institute was formed on September 4, 1874, with Colenso elected secretary-treasurer, also as a member of council.

In 1872 he was appointed Inspector of the Common and Private Schools under the Provincial Council.

When Provincial Councils were abolished in 1876 Colenso continued until 1878 as Inspector of Government Schools.

In 1878, at 66, Colenso retired and took time to enjoy his home and garden, and to set in order his shells, fossils and herbarium.

Soon he returned to botany with all his old enthusiasm.

He often travelled to Dannevirke and Woodville and his solitary figure was often seen as he hunted in the remnants of the great forest – the Seventy Mile Bush.

The tangible results were seen in the sketches and specimens which accompanied the papers he read at every Institute meeting in 1879.

He resigned office as secretary of the Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Institute after ten years of honorary service.

In 1885 certain Fellows of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Hooker, and three members of the New Zealand Institute: Dr Hector, Sir Walter Buller and Sir J E J Von Haast nominated him for election as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a signal honour indeed.

He was elected in 1886.

His name stands with those of two famous Fellows associated with New Zealand, Captain James Cook and Lord Rutherford, but only Colenso had done all the work thus recognised entirely in New Zealand.

Moreover it was done when he was without contact with other workers in the same field. Colenso had the friendship of some leading men in Hawke’s Bay.

He was a staunch friend of the Maori. Between Te Hapuku, their chief, and Colenso was sincere friendship based on mutual respect and trust.

Colenso held in high esteem the work of Donald McLean, and vice versa.

A friend from the earliest days of European settlement was Henry Stokes Tiffen, Commissioner of Crown Lands.

He and Colenso shared a love of trees. On the basis of shared interest in botany and education was the genial, kindly Henry Hill who was for 37 years School Inspector for Hawke’s Bay.

They both enjoyed the friendship of a younger man, scholarly William Dinwiddle, [Dinwiddie] the legally trained editor of the Hawke’s Bay Herald.

All three were writers, all three were keen members of the Institute.

The Reverend. William Colenso who was born in Penzance, England, in 1811 died in Napier, in 1899.

He was buried close to the entrance of the first Napier cemetery on Napier Terrace.

His old friend, Henry Hill wrote: “The scene . . . was sad, and withal beautiful.

An old man full of years and honours was borne to his resting place. Yet no wife, no child, no relative was there to mourn his passing.

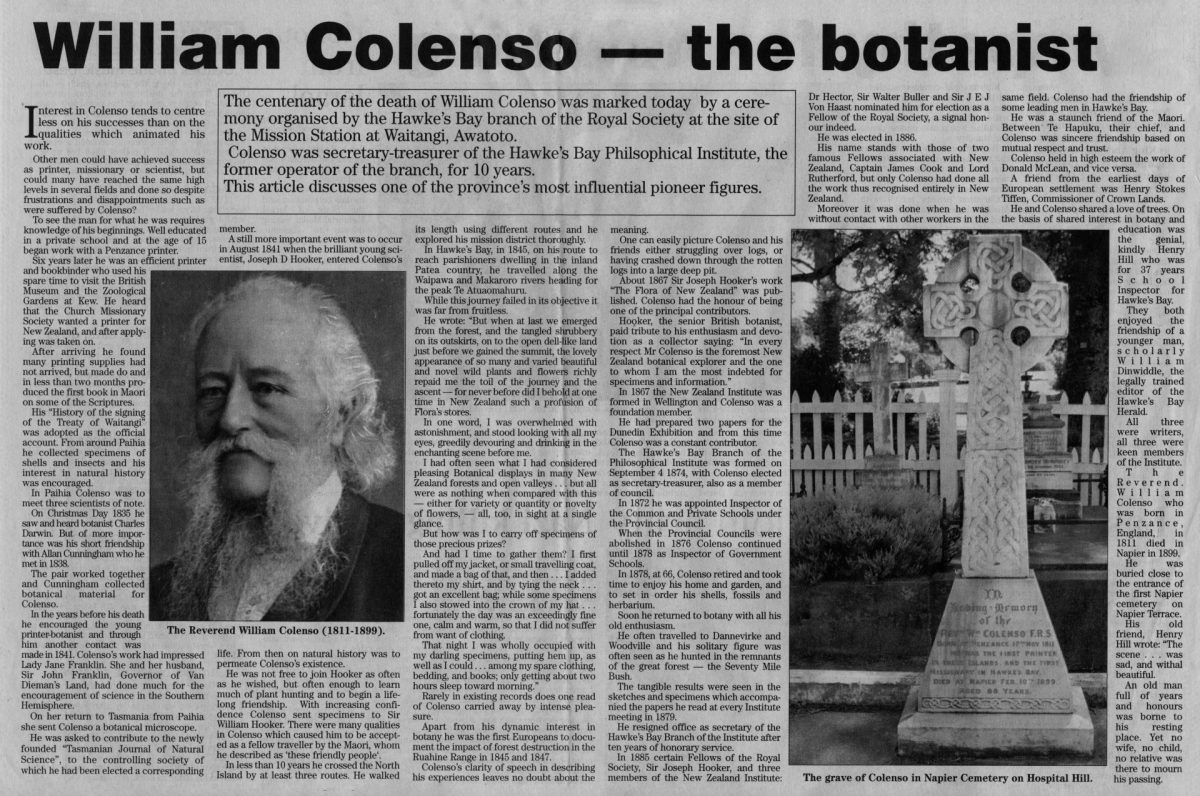

Photo captions –

The Reverend William Colenso (1811-1899).

The grave of Colenso in the Napier Cemetery on Hospital Hill.

Epitaph –

“In

Loving Memory

of the

REV’D. WM. COLENSO F.R.S

BORN AT PENZANCE 17th. NOV. 1811

HE WAS THE FIRST PRINTER IN THESE ISLANDS, AND THE FIRST MISSIONARY IN HAWKE’S BAY.

DIED AT NAPIER FEB. 1Oth. 1899

AGED 88 YEARS.”

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.