our past

matthew wright

Hawke’s Bay on the main truck line?

New Zealand’s history could have been very different if the main truck line had gone through Hawke’s Bay, which seemed a real possibility in the early 1880s. This is the seventh in a series of 12 articles.

Treasurer Julius Vogel hit upon the idea of a main trunk line between Wellington and Auckland in the late 1860s.

What he had in mind was a skeletal national rail system that could bolster the economy and create a platform for which the settler free market could flourish.

But he had no firm ideas on the route, and was hobbled by a shortage of funds. As a result he had to favour branch lines, including one running south from Napier and another running north through the Wairarapa.

Both lines were under construction by the mid 1870s. Debate then brewed in Hawke’s Bay over a route to Taupo.

The argument for both road and rail centred around two possibilities, either a modification of the Titiokura track, or a wholly new route via Puketitiri. The latter was favoured J B Ellman who, in August 1879, wrote to the Hawke’s Bay Herald to explain there was “no choices of routes, there was only one”.

Ellman described the Titiokura path as a “mad freak”, and proposed a line beginning near Puketapu, running through Omahu, Moteo, Rissington, Puketitiri bush and up to Pakatutu. From there it went along the Aripia valley, crossing the Mohaka by bridge.

At the point Ellman had in mind the river was only 80 feet (24 metres) wide, and a rocky outcrop made “a splendid place for either a suspension bridge or for throwing a single arch across without any piers obstructing floods”.

Ellman called for “two careful surveys and plans” to prove his case. He had “more faith in the two plans exhibited side by side than any amount of scribbling on tables” and was sure the comparison would cause the public to “wonder what has induced the authorities to blindly follow Maori advice and improve…the war track”.

The sceptre was taken up by an anonymous correspondent to the Herald who proposed a further alternative from Takapau to Maraekakaho, then up the Ngaruroro valley – missing out Hastings and Napier altogether.

Those ideas were purely local, but a Napier-Taupo connection was also being considered by central Government as part of a link between Auckland and Wellington.

In 1880 the choice of a main trunk route was far from settled.

State-funded rail ran from Auckland to Te Awamutu on the boarders of the King Country. The state line out of Wellington went east over the Rimutakas, towards the other state line coming south from Napier.

A commission formed in 1880 certainly viewed a Wairarapa – Hawke’s Bay rail connection as part of a trunk line. However, money was at a premium and the same commission not only axed the Napier-Taupo railway project necessary to an East Coast main trunk, but recommended not taking further overseas loans out before the end of 1892.

Spurred by Taranaki’s efforts to have the main trunk run through New Plymouth, Napier businessman M R Miller took up the sceptre in mid-1882.

He told the Napier Chamber of Commerce that “Hawke’s Bay people had been too modest in their demands for a main trunk – they had been above log-rolling – and consequently they had been entirely passed over”.

He had Ellman’s plans and hoped to persuade the Government to survey the route.

The Government had other ideas. Although King Tawhaio made official peace with the Government in 1881, the King Country remained essentially independent. A railway seemed an obvious way of bringing these lands into line.

Tawhaio would not permit a line to be built, but, in 1882, Ngati Maniapoto chiefs Huatara Wahanui and Rewi Maniapoto sidelined the chief. They regarded railway as a source of essential income and, after negotiations with the Government, agreed to let surveyors look for routes through their territory. They also offered land for the permanent way.

The route seemed settled, but Hawke’s Bay’s pastoralists did not go down without a fight. Despite the abolition of the provinces in 1875, they still had a strong voice in central Government.

When formal efforts to locate a route began in February 1883, one of the survey parties was sent to investigate a line from Napier into the central region. Another looked into Taranaki. Both came back with bad news: The terrain – particularly between Napier and Taupo – was just too rugged.

That left only the central route through the plateau west of Taupo as a viable alternative, but, in any cases, the politics of the time demanded that choice.

And so Taumarunui, not Takapau or Te Pohue, ended up on the main trunk line.

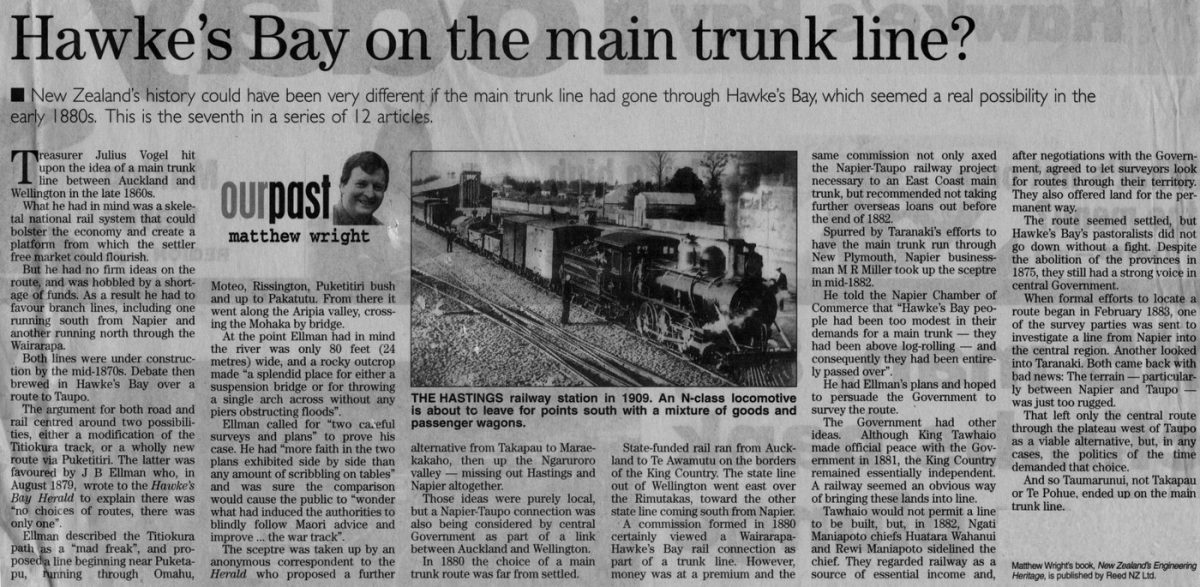

Photo caption – THE HASTINGS railway station in 1909. An N-class locomotive is about to leave for points south with a mixture of goods and passenger wagons.

NEXT: understanding the 1931 earthquake

Matthew Wright’s book, New Zealand’s Engineering Heritage, is published by Reed NZ Ltd.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.