After World War II broke out, he volunteered when second echelon was about to head overseas, but again his eyesight let him down.

Ray finally got an opportunity to sign up with the Territorials, but that involved another eye-sight test.

“By that time, I had memorised the chart so I got a grade one ranking with grade three eyesight.”

Fifteen months of his World War II service was spent on the remote Fanning Island.

The coral atoll was a vital communication link where cable ran from Australia and New Zealand to Fiji and Fanning Island and on to Hawaii.

In World War I the cable had been cut by a German raider which then tried dragging it away, but it snagged on the reef. Australia operated the cable station, and it was feared another attempt would be made to sabotage the link.

What was to have been a six-month posting to Fanning, turned into a 15-month stint when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour and the war entered a new phase.

The coral island with its lagoon and reef was mainly flat with hundreds of coconut palm trees.

Lookout posts were up tall palm trees and also an old ship’s mast provided the vantage point for a third.

“We had one week on and one week off, which was spent back at camp.”

Long hours were spent reading or fishing in the lagoon – catches providing the only fresh food other, than coconut milk, that the guards were to get.

The odd visit by Catalina flying boats, and once even an American destroyer, served as welcome distractions. There was never to be any sign of the Japanese in those 15 months

Sending messages back home was limited to telegrams or cables which were tapped out in Morse code.

But a highly successful brief system left even today’s text messaging for dead. A list of messages could be looked over, the number alongside each one would then be selected and tapped out.

Ray remembers selecting number 25, which ensured “Happy Birthday Mum” arrived at home for his mother’s special day.

“You couldn’t select the actual words which went into the message, just the number.”

It was also the way he was to send congratulations to his friends June and John Greenfield when they married.

His return to New Zealand and the post war years were to bring big changes. First there was his marriage to Eunice, who had been introduced to him by her sister.

“She had six sisters and as there was still rationing, their combined rations for sugar and eggs enabled them to make a wedding cake.”

Ray attended university to pass his accountancy examinations and, after shifting to Auckland and living at Takapuna, he was able to build a boat for sailing in the harbour.

In the days before the Auckland Harbour Bridge was built he caught the daily ferry across to the city for work – a journey he says on which many people made friends.

The Griffiths have enjoyed their retirement years in Taupo, persuaded to come through the friendship with the Greenfields.

There was also the fishing which had already proved a pull over the years for Ray. He, John and other friends had an informal fishing circle and would spend many happy hours casting in rivers and lakes in the region.

“I’m the only one left these days.”

The Griffiths’ garden shows the signs they are keen gardeners.

The most impressive sight though is the kowhai tree standing sentinel at the garden gate. It is full of tuis – a good 20 of them chirping away – keeping a friendly guard on the man who once did that for adopted nation.

Photo captions –

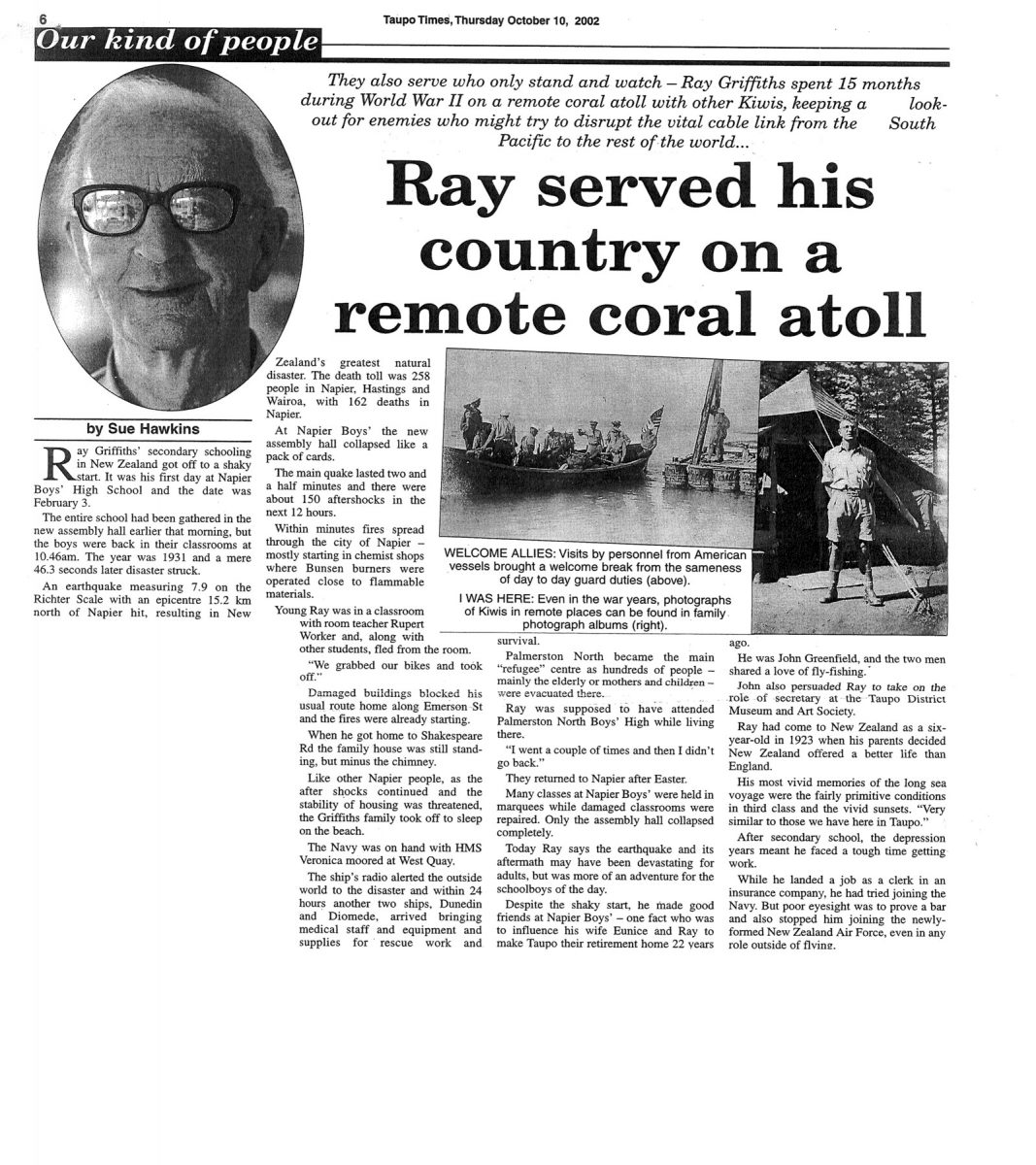

CABLE STATION: The all-important cable station (left) which was run by Australians and guarded by New Zealanders during World War II.

KEEPING WATCH: Lookout posts up coconut palms were manned on a weekly basis as the men watched out for any signs of enemy ships.

PERILOUS TIMES: Not all danger came from possible arrival of enemy shipping – coconut crabs (above) could make collecting coconuts, a dangerous occupation.

TOP WHEELS: Every young man’s dream is to have his own wheels (left).

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.