Before the mountain

Fortune plays its part

Luck and coincidence helped New Zealanders, including Hillary, join what was supposed to be a British expedition. JOHN HENZELL recounts the events that led to May 29, 1953.

The thought of the 1963 Everest expedition having no New Zealanders on the team seems unthinkable now.

But that’s what could easily have happened if not for a series of seemingly unconnected events – everything from Adolf Hitler’s geopolitical ambitions in Europe to a threatened boycott by other Everest team members – that combined to put Sir Edmund Hillary and his climbing partner George Lowe on an ostensibly British expedition.

Hillary is blunt about what he believes would have happened if he and Lowe had been left out – we would not be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the ascent of Everest.

The claim is not as arrogant as it might sound. Throughout the war years, the European Alps were off limits to British alpinists.

However, right up to the early 1950s the tough restrictions on taking money out of cash-strapped post-war Britain still put the brakes on climbers gaining experience on the high peaks of Europe.

So when the British began picking climbers for the 1953 Everest Expedition there were a lot of bold and skilled rock climbers but precious few with extensive snow and ice experience, which is the predominant type of climbing in the Himalayas. And the wild valleys of highest Nepal were a long way from the European style of mountain huts and guided ascents that Hillary later described as “so different to the hardy mountaineering we’d been accustomed to that it was a little like a rest cure.”

Here at the other end of the world, none of those restrictions applied to what was, by chance, a particularly talented generation of Kiwi mountaineers.

The dramatic upsurge of the Southern Alps from the Tasman Sea meant massive glaciation and dodgy weather. And to get into the big hills meant shouldering a huge pack and going into the mostly untracked wilderness, with the knowledge you only had yourself to get out of trouble.

This was the environment where a young Hillary learnt to climb.

At the age of 20, the shy, awkward and conflicted beekeeper spent the first summer of World War 2 on a tour of the South Island. The high peaks of the Southern Alps made an immediate impact and in the lounge of the Hermitage, he basked in the elation of having stamped around in some old avalanche snow in a nearby gully. Moments later, the appearance of two climbers who had just completed a grand traverse of the three peaks of Mount Cook made him feel utterly insignificant.

Six years and some rather neglected beehives later, Hillary had built up the skills to climb Mount Cook for himself. Fittingly it was in the company of the man who became his climbing mentor, guide Harry Ayres, who added skill and finesse to the strength and determination Hillary already possessed.

Hillary says Ayres was the greatest climber of his generation, and possibly any New Zealand generation. Better yet, he describes his gratitude when Ayres “took me under his wing and, for three marvellous seasons, we climbed the big peaks together.”

By 1950, the Himalayas beckoned for New Zealand’s best and brightest mountaineers, with a team of 10 making the wildly ambitious plan to tackle Everest the following year on the first all-Kiwi expedition to the range. By the time reality intervened, Hillary was invited onto a team of four attempting Mukut Parbat, a peak 1600m lower than Everest at the head of the Ganges in the Indian Himalaya.

In another one of the twists of fate that took Hillary towards the summit of Everest, also kicking around the Himalaya in 1951 was Eric Shipton on an Everest reconnaissance. As the leader of some of the pre-war expeditions to Everest, Shipton had a soft spot for Kiwis because of the ice-climbing ability and ruggedness of Waitaki teacher Dan Bryant, who had been on his Everest expedition in 1935. He wrote later “because of the great respect and liking I had for Dan” he spontaneously invited two of the New Zealand team to join him.

When the four New Zealanders had to choose who among them should go, it created an acrimonious argument that resulted in permanent rifts among the team. (The irony was that Shipton said later he was happy for all four to have come, since they were paying their own way anyway.)

In the end, time money and strength of will saw the New Zealand expedition leader, Earle Rickford and Hillary join Shipton.

Shipton admired anyone who could travel fast with heavy packs over difficult ground and wasn’t too fussed about creature comforts, so it was little wonder that he got on well with Hillary. The bond was strengthened by a second reconnaissance in 1952 (a Swiss team had the sole permission to attempt Everest that year) with Hillary, Lowe and Riddiford. When Riddiford hurt his back, Shipton was planning to attempt Everest in 1953 with a six-man climbing team of whom half were to be New Zealanders – Hillary, Lowe and Harry Ayres.

Then came the bombshell that would have seen the expedition without any New Zealanders – Shipton was dumped as leader in favour of John Hunt a senior military man whom the Himalayan Committee thought would be more likely to organise a successful ascent.

Hillary recalls feeling that they were going to be excluded, but he was so upset about the boorish dismissal of Shipton “that I doubted whether I cared if I went at all.”

“I’m sure it’s absolutely true that I wouldn’t have been involved in Everest if Shipton hadn’t invited George Lowe and me to be in the party,” he said.

“When John Hunt took over the leadership he emphasised that he wanted all the members of the party to be people he knew and he’d assessed. He hadn’t met George or me so he was a bit reluctant to take us. That would have been a big disaster for the expedition, I would have thought.

“However, we had the support on our side and all the other British climbers we’d been with in the previous two years (Charles Evans, Tom Bourdillon and Alf Gregory) all said that if George and I weren’t asked, then they wouldn’t go either. As a result of that, John Hunt conceded.

“Its a very good thing we did stay in the team because of our skills at snow and ice climbing. The British climbers were all really hot stuff rock climbers but they weren’t all that strong on ice and snow. We were, just because we happened to have some pretty good mountains in New Zealand and we’d climbed a lot of them.”

Having remained on the expedition against the original wishes of the leader, Hillary wrote to Hunt promising “to do our best to more than justify our inclusion.”

And the rest became history.

Photo captions –

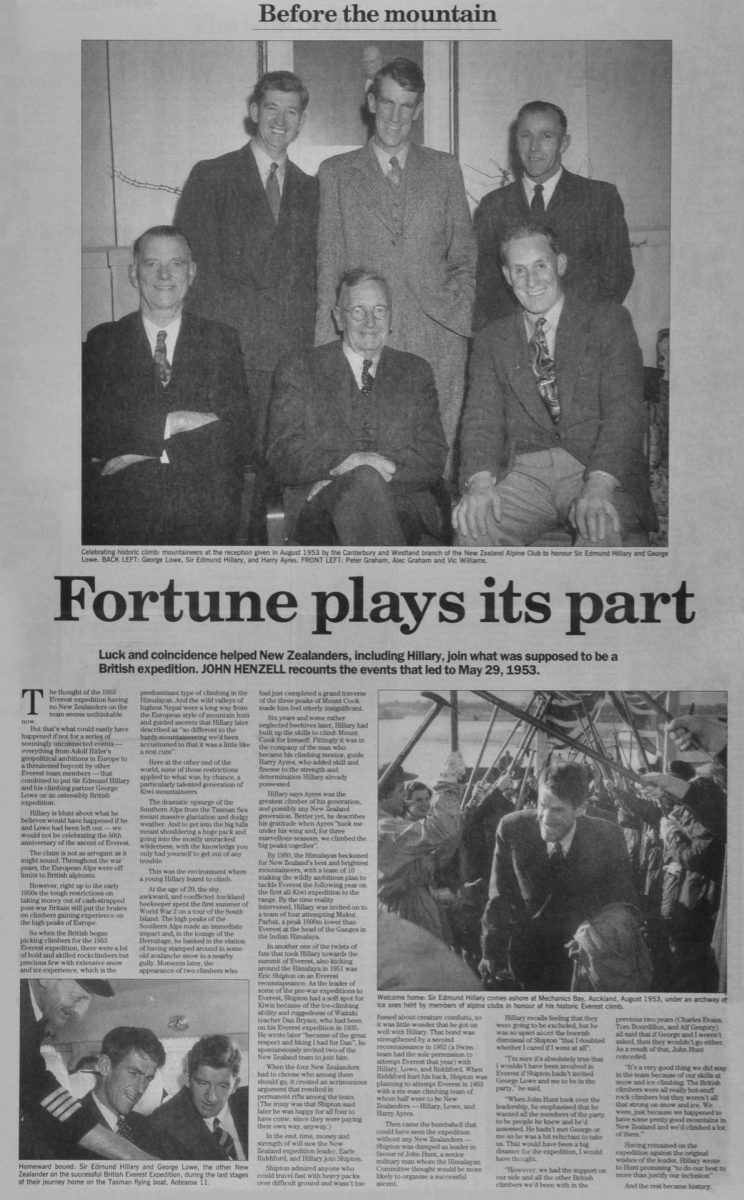

Celebrating historic climb: mountaineers at the reception given in August 1953 by the Canterbury and Westland branch of the New Zealand Alpine Club to honour Sir Edmund Hillary and George Lowe. BACK LEFT: George Lowe, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Harry Ayres. FRONT LEFT: Peter Graham, Alec Graham and Vic Williams.

Homeward bound: Sir Edmund Hillary and George Lowe, the other New Zealander on the successful British Everest Expedition, during the last stages of their journey home on the Tasman flying boat, Aotearoa 11.

Welcome home: Sir Edmund Hillary comes shore at Mechanics Bay, Auckland, August 1953, under an archway of ice axes held by members of alpine clubs in honour of his historic Everest climb.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.