Guardian of the lake

Lou Dolman talks to PETER DE GRAAF about a lifetime of policing the wild and remote Urewera Ranges, sharing his love of Lake Waikaremoana with others, and preserving the memory of the lake’s long departed Maori elders.

They say Lake Waikaremoana was formed when a trapped taniwha, or spirit guardian, thrashed about in its desperation to reach the sea.

There’s another guardian at Lake Waikaremoana – although he’d be unlikely to describe himself that way – who for almost 30 years was the area’s only policeman, who has plucked countless lost hunters and trampers from the bush, and who has tried to make sure the wishes of long-dead Maori elders are respected.

Born in Ngatapa, near Gisborne, Lou Dolman started out as a shepherd in Hawke’s Bay when the rabbit plague was at its worst.

“They started strychnine poisoning the rabbits, and all my good dogs got poisoned,” Lou says.

“I was a bit distressed about it, and a chap that used to come out rabbit hunting on the farm convinced me to join the police force for a look around.”

That was in 1947; a “look around” turned into 38 years. For 29 of those he was the sole police officer in the isolated hydro settlement of Tuai, an hour north of Wairoa and 15km from Lake Waikaremoana.

As the only policeman, he was also the bailiff, arms officer, probation officer and alien officer (in charge of migrants, not extraterrestrials). He had no telephone or radio, had to use his own vehicle, and with no ranger in those days, he looked after the park as well.

“Being a policeman was quite different then – you were given a district and told to look after it. How you looked after it was up to you.”

The highlight of his career was the 1953 royal tour, when he was one of 20 policemen accompanying the royal party.

“The weather was great, the crowds were great, everybody was happy . . . Back then, if anyone didn’t want to see the queen, they stayed home.”

The lowest point was the 1951 waterfront strike. For five weeks he guarded Wellington’s wharves in the wet and cold, starting at 5am and, if he was lucky, knocking off at 9pm.

After working in Napier, Auckland and Ruatoria, Lou was transferred to Tuai in 1956. There was full employment and little trouble in the hydro villages, but search and rescue kept him busy.

“Being a policeman was quite different then – you were given a district and told to look after it. How you looked after it was up to you.”

In those days the bush was crowded with deer and the roads were littered with flattened possums – you couldn’t drive without hitting them, Lou says.

When the deer cullers pulled out in 1957, private hunters streamed in by the thousands and “got lost left, right and centre”. One night Lou had three search parties out at once; with no radios, signalling was by rifle shots.

Tired of bashing around in the bush for stray hunters, the park board’s chief ranger had proper tracks and signposts put in wherever people got lost.

“He said it was quicker to put a track in than to go looking for people, and eventually it cut our work right down.”

In later years, helicopter poaching became Lou’s biggest headache.

“I had a Toyota Landcruiser and they had helicopters, so it was a bit one-sided . . . But there was so much bad feeling and so many shots were fired, we had to do something or someone was going to get killed,” Lou says.

Poaching declined when the price of wild venison fell, but ill-feelings remain to this day.

“It’s easy to start an argument, but hard to stop one,” he says.

When Lou retired in 1985 he moved up the hill to Onepoto, a few minutes walk from the lake and with a view – when the Ureweras’ infamous mist clears – of the 1200m peak Ngamoko.

Retirement meant more time for the Friends of Te Urewera National Park, a group he chaired for 25 years, and a chance to get stuck into cutting tracks.

In the park’s early years, until the Cave Creek disaster in Paparoa National Park changed everything, most of the work was done by volunteers.

One of Lou’s “little projects” was a track up to a lookout point high above the road that skirts Lake Waikaremoana.

“To see the lake properly you’ve got to get up high, but a lot of people can’t make it up to Ngamoko or Panekiri – I wanted a place where you could get the same view without it being too strenuous.”

It took 25 years to get permission to put in the track, and a good few years after that to finish the job. Now the track to Lou’s Lookout clambers up through a jumble of massive boulders, remnants of the landslide 2000 years ago that created the lake, to a bluff with spectacular views across Waikaremoana.

With the help of other enthusiasts, he also cut a track to the Onepoto moa caves, and reopened a historic Maori trail elders had shown him decades earlier.

For many years Lou also gave weekly talks at Camp Kaitawa, an outdoor education centre in a former hydro village school, and took the children up Ngamoko.

“Whenever I talked to them years later, they’d say their fun day was at the caves, but the day that really impressed them was going over Ngamoko, because they’d climbed a mountain,” Lou says.

One of his most memorable trips followed a heavy fall of snow, and after slogging much of the way up he told the teacher it was too tough and they would have to turn back.

“But he said one child, who was born with club feet and had umpteen-dozen operations, had made up her mind she wanted to climb a mountain. I thought if she’s got this far, I’ll get her the rest, so I got her behind me and cut steps through the snow all the way.”

At 77, Lou is still putting in tracks, though closer to home these days.

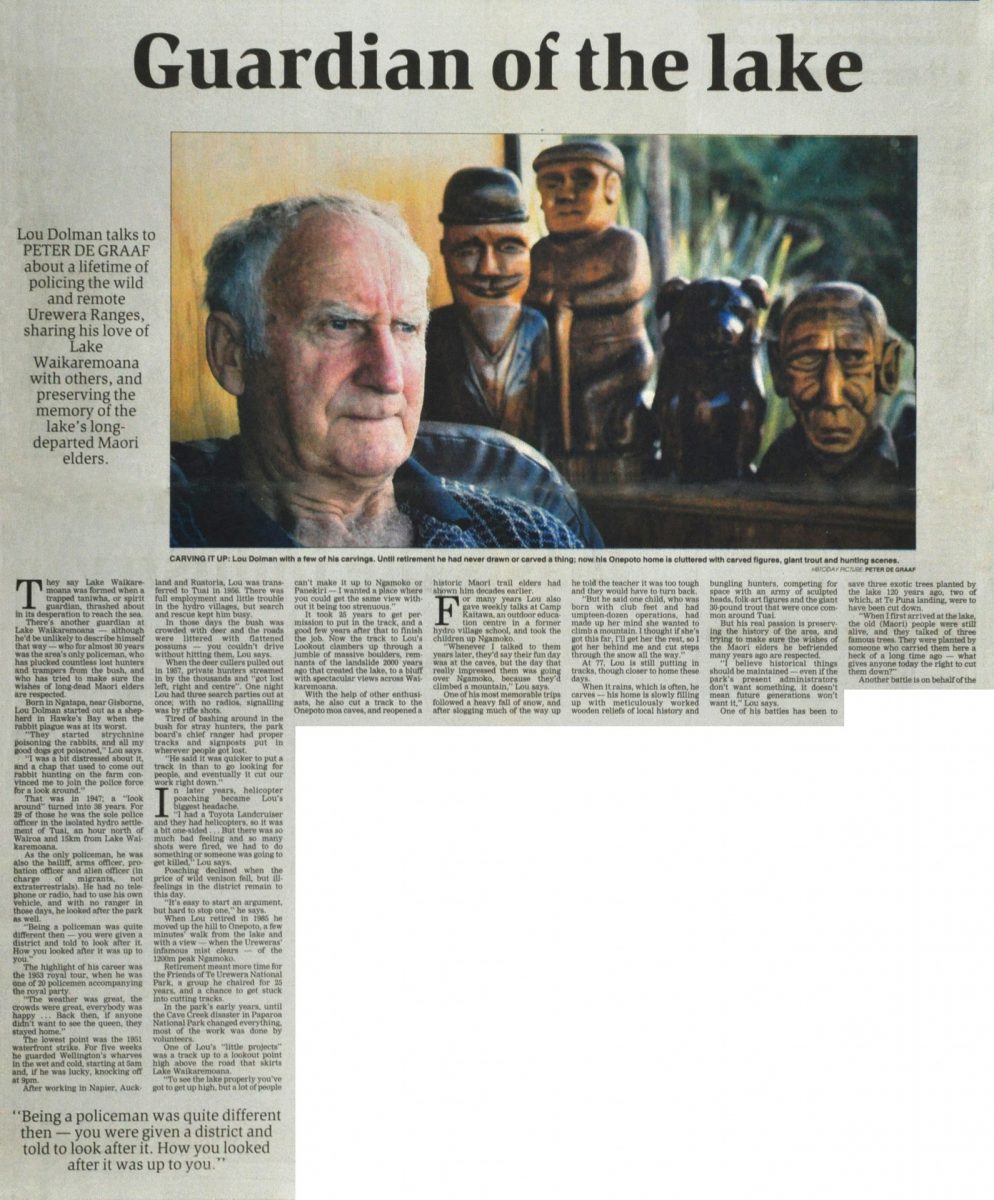

When it rains, which is often, he carves – his home is slowly filling up with meticulously worked wooden reliefs of local history and bungling hunters, competing for space with an army of sculpted heads, folk-art figures and the giant 30-pound trout that were once common around Tuai.

But his real passion is preserving the history of the area, and trying to make sure the wishes of the Maori elders he befriended many years ago are respected.

“I believe historical things should be maintained – even if the park’s present administrators don’t want something, it doesn’t mean future generations won’t want it,” Lou says.

One of his battles has been to save three exotic trees planted by the lake 120 years ago, two of which, at Te Puna landing, were to have been cut down.

“When I first arrived at the lake, the old (Maori) people were still alive, and they talked of three famous trees. They were planted by someone who carried them here a heck of a long time ago – what gives anyone today the right to cut them down?”

Another battle is on behalf of the

[article incomplete ]

Photo caption – CARVING IT UP: Lou Dolman with a few of his carvings. Until retirement he had never drawn or carved a thing; now his Onepoto home is cluttered with carved figures, giant trout and hunting scenes.

HBTODAY PICTURE: PETER DE GRAAF

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.