HEALING MEMORIES: A priest who was injured by terrorists is back in the Bay.

Crippled priest to focus on forgiveness

KATHY WEBB

The outpouring of emotion surrounding the return of the Unknown Warrior to New Zealand has come from a secular society in search of identity and acknowledgement of the past.

That’s according to Father Michael Lapsley, an Anglican priest and former Hastings man and who lost his hands to a letter bomb sent as punishment for his political views by the last white Government in South Africa.

Sitting in the lounge of his mother’s flat in Napier, Father Lapsley speaks with a smooth and modulated voice tinged with a hint of South African vowels.

“New Zealand families have been shaped by war, and people who never came back” he says.

“It has shaped families and lives. Every story deserves a listener, and the emotion surrounding him (the Unknown Warrior) is complex. It has many layers.

“As New Zealand has become more and more secular there are still symbolic ways as human beings we need to make sense of our past. It’s not just about identity and nationhood but about memory and acknowledgement of the past.

“It’s fortunate New Zealand has not gone to the moral war in Iraq. Because (we’re) not there, and not at war anywhere, it frees us to remember and yet not romanticise war, but to acknowledge the sacrifice that happened.

There’s also a deeper affliction – those who came back damaged and how that played itself out as families. Sometimes I think if you focus on the heroes you don’t think about the people who have gone to war.”

In a similar way, the reaction to National leader Don Brash’s Orewa speech on race relations “suggests there is a journey to be travelled”.

“In divided societies, people have not deeply heard the stories of others, and the feelings they have.”

Father Lapsley will speak at St John’s Cathedral tomorrow about his work with the Institute for Healing Memories, which was set up in [in] Cape Town in August 1998 to encourage sufferers of violence to tell their stories, so as to put their experiences behind them.

His speech will focus on the themes of forgiveness and acknowledgement.

Father Lapsley was working as chaplain to the dissident African National Congress in South Africa in April 1990, three months after the release of Nelson Mandela from prison, when he received a letter bomb that blew off his hands. No one ever found out exactly who had sent it, but the chain of command was clearly from within the Government.

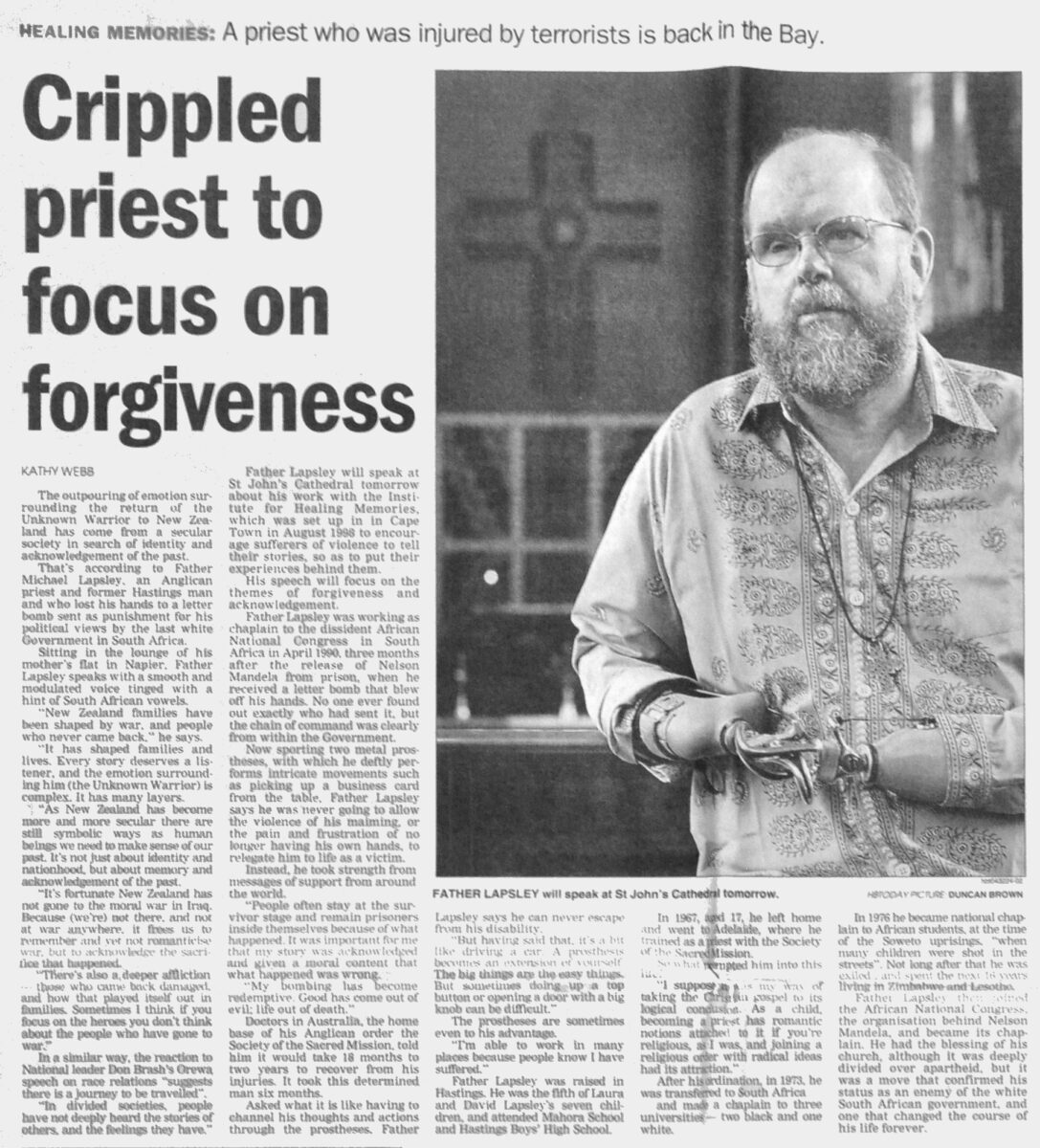

Now sporting two metal prostheses, with which he deftly performs intricate movements such as picking up a business card from the table, Father Lapsley says he was never going to allow the violence of his maiming, or the pain and frustration of no longer having his own hands, to relegate him to life as a victim.

Instead, he took strength from messages of support from around the world.

“People often stay at the survivor stage and remain prisoners inside themselves because of what happened. It was important for me that my story was acknowledged and given a moral content that what happened was wrong.

“My bombing has become redemptive. Good has come out of evil; life out of death.”

Doctors in Australia, the home base of his Anglican order the Society of the Sacred Mission, told him it would take 18 months to two years to recover from his injuries. It took this determined man six months.

Asked what it is like having to channel his thoughts and actions through the prostheses, Father Lapsley says he can never escape from his disability.

“But having said that, it’s a bit like driving a car. A prosthesis becomes an extension of yourself. The big things are the easy things. But sometimes doing up a top button or opening a door with a big knob can be difficult.”

The prostheses are sometimes even to his advantage.

“I’m able to work in many places because people know I have suffered.”

Father Lapsley was raised in Hastings. He was the fifth of Laura and David Lapsley’s seven children and attended Mahora School and Hastings Boys’ High School.

In 1967, aged 17, he left home and went to Adelaide, where he trained as a priest with the Society of the Sacred Mission.

So what tempted him into this life?

“I suppose it was a way of taking the Christian gospel to its logical conclusion. As a child, becoming a priest has romantic notions attached to it if you’re religious, as I was, and joining a religious order with radical ideas had its attraction.”

After his ordination, in 1973, he was transferred to South Africa and made a chaplain to three universities – two black and one white.

In 1976 he became national chaplain to African students, at the time of the Soweto uprisings, “when many children were shot in the streets”. Not long after that he was exiled, and spent the next 16 years living in Zimbabwe and Lesotho.

Father Lapsley then joined the African National Congress, the organisation behind Nelson Mandela, and became its chaplain. He had the blessing of his church, although it was deeply divided over apartheid, but it was a move that confirmed his status as an enemy of the white South African government, and one that changed the course of his life forever.

Photo caption – FATHER LAPSLEY will speak at St John’s Cathedral tomorrow. HBTODAY PICTURE: DUNCAN BROWN

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.