‘Wahine girl’ took control

Few people who work at Hawke’s Bay Hospital realise their work colleague Sue Willoughby is a hero. It’s not something she likes to talk about but she did speak to KATE NEWTON about that fateful day 38 years ago.

It was April 10, 1968, and 18-year-old aircraftwoman Sue Willoughby had just finished her recruit course for the Royal New Zealand Air Force in Christchurch.

She was looking forward to a couple of weeks holiday at home with the family in Fielding and excited about spending a night on the inter-island ferry Wahine which had been advertised as a “floating hotel”.

Having boarded the Wahine the evening before in Lyttelton, Sue shared her cabin on the lowest deck with three other aircraftwomen.

The women had woken at dawn and dressed in their Air Force uniforms.

Just before 7am Sue felt the boat shudder, lurch upwards, and then come down sideways.

Announcements over the intercom explained the ship was aground on Barrett’s Reef at the entrance to Wellington harbour but they were told there was no danger, to stay calm and report at their muster stations.

The southerly storm was at its height with winds gusting to 155km/h but Sue was stuck in a packed windowless corridor for hours.

As the ship drifted down the harbour, dragging its anchors, the passengers sang to pass the time.

“Rocking, rolling, riding, out along the bay. . .”

Still listening to instructions that they were in no danger, the passengers were told to get their life jackets and make their way to an open part of the ship.

Sue went to a seated area where people were starting to worry.

There were no life jackets to fit the children and the lifeboats on the side of the ship that was high in the air were unable to be thrown out into the water.

“At some stage the boat which was already a bit skewy became more so,” Sue said.

It was just after 1pm when passengers heard the call to abandon ship.

After being told they were in no danger, many of the passengers were stunned. Some had removed their life jackets and were using them as pillows. Others didn’t know which side was starboard (right) and began to make their way up to the high side of the boat.

Sue started helping families into life boats and was comforting one couple with three young children.

She offered to take their middle child, a little boy, and took off his life jacket to get a better grip on him.

All the lifeboats had already been lowered and the inflatables were blowing away so Sue leapt into the water holding the young boy tightly.

After the two had spent 20 minutes in the freezing water and were almost exhausted a life boat picked them up.

Sue knew it was important to keep the boy talking and awake so told him all the fairy tales she could remember.

“Because I was concentrating on him I wasn’t really panicked. It was good to have someone to help focus my mind on surviving,” she said.

Sue couldn’t feel her legs from the cold. Her shoes had come off and her stockings were shredded by the wooden deck of the ship. Her shins were bruised, but she was lucky.

Many of the 51 who died were in the first lifeboat which was swamped soon after launching.

As some of the life rafts approached the shore at Eastbourne, waves as high as six metres capsized them.

Some drowned while other people were dashed against the rocks of the pounding surf and their bodies washed up along the stretch of beach.

The storm had left debris on the road and prevented emergency vehicles form getting to the beach, meaning some who made it to the shore alive then died from exposure.

Sue comforted the children in her boat and watched as the waves crashed over the Wahine.

“I think your mind protects you so you stop seeing the enormity of it all in a situation like that,” Sue said.

Sue’s boat came ashore at Wellington harbour and she carried the boy to safety. It wasn’t until then that she started to cry.

The survivors were taken to the Railway Station where the little boy’s mother recognised him.

She was relieved to see her son but distraught as she had lost her youngest when he slipped through the life jacket and was lost in the raging ocean.

“It was chaos. There were so many relatives who had come to see their families. People were watching you as you walked through.” Sue said.

She kept in contact with the family for a while but eventually lost touch.

All of Sue’s fellow aircraftwomen survived the sinking and Sue’s Dad came down and took her home to Fielding.

She was known as the Wahine Girl from then on at the Air Force base in Woodburn.

A fear of being in aeroplanes and on the ground floor of department stores haunted Sue for a few years after the sinking but she has since overcome the phobias.

Her handbag was recovered from the sunken wreck and delivered to her a few weeks later, but because she had just finished the course and was shifting, all her belongings had been lost.

“At that age things still happen to you and I became aware very quickly that I could have much more control over my life,” Sue said yesterday.

“I could survive and I did a lot of deliberate things like helping the family. I realised I could take control in difficult situations. ”

It became obvious to Sue that she belonged in the public service sector and she soon started training as a psychiatric nurse.

That career choice turned out to be the perfect one, with Sue moving a year ago from Dunedin to work at Hawke’s Bay Hospital as the manager of the mental health inpatient unit.

Sue doesn’t think about that ill-fated sailing often but likes to keep it in her mind around the anniversary.

She hopes to make it to the 40th anniversary in two years.

“It’s something like that that makes you realise you are mortal and you only have a certain time on this Earth,” she said.

FACTBOX

The twin-screw turbo electric steamer Wahine was built at Govan, Scotland, in 1966 for the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand Ltd by Fairfields Ltd of Glasgow.

It was the second ship to bear the name and at 8948 tons, the largest in the company’s fleet. Referred to as a Steamer Express by the company’s publicity department, at 488 feet (149m) long she was also one of the largest ferries in the world.

The Wahine could accommodate 927 passengers in cabins on six decks and in greater comfort than in any of her predecessors.

After the sinking, a Court of Inquiry was convened. In December 1968 it was to return with a list of errors and omissions made both onshore and aboard the ferry.

At the same time, it was noted that these occurred under very difficult and dangerous conditions.

The Inquiry found that the primary reason for the Wahine’s loss was the presence of water on the vehicle deck.

Fault was found with Captain Hector Robertson for failing to report this to those onshore and also for not reporting that the ship’s draught had increased to 22 feet after striking the reef.

Photo captions –

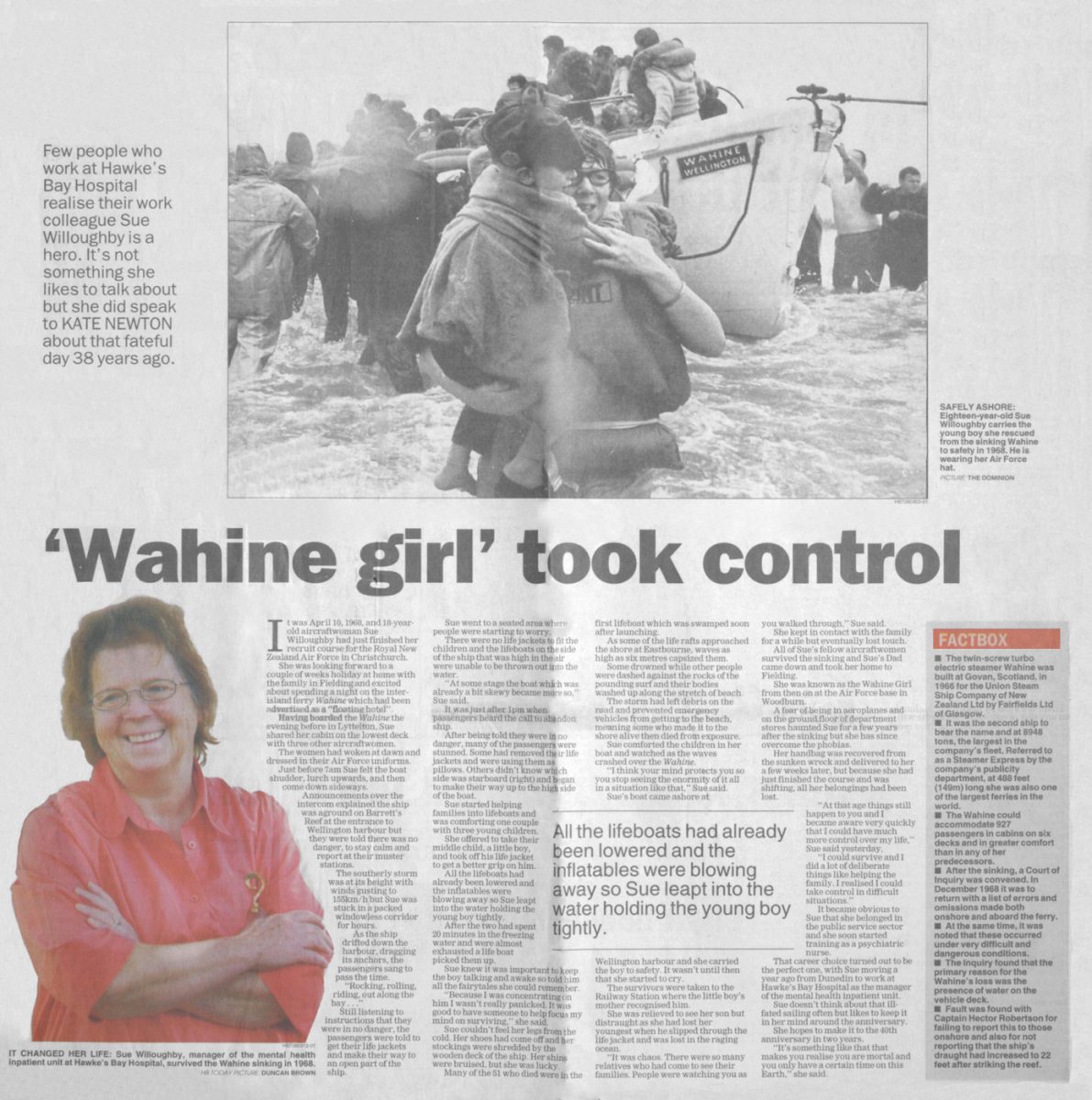

SAFELY ASHORE: Eighteen-year-old Sue Willoughby carries the young boy she rescued from the sinking Wahine to safety in 1968. He is wearing her Air Force hat.

PICTURE: THE DOMINION

IT CHANGED HER LIFE: Sue Willoughby, manager of the mental health inpatient unit at Hawke’s Bay Hospital, survived the Wahine sinking in 1968.

HB TODAY PICTURE: DUNCAN BROWN

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.