Bay man in thick of Dunkirk conflict

Michael Fowler

Historic Hawke’s Bay

The first book I wrote was a history on Hawke’s Bay accounting called From Inkwells to Email.

It flopped.

Broadcaster Paul Henry interviewed me and asked me, in so many words, “Why would I do such a thing?”

The Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Michael Cullen, who launched the book at EIT Hawke’s Bay in 2005, told me he wrote a history called Centennial History of the Otago District Law Society – and suggested to me that we had both had relatively challenging subjects to write about.

Of the seven books I have released so far (my eighth, a history of the Hawke’s Bay Opera House will hopefully soon be released by the publishers, Hastings District Council), this is one of my best.

But perhaps I should have called it a history of the lives of accountants, as that’s in effect what it was about.

Recently I saw the film Dunkirk, based on the events of the 1940 evacuation at Dunkirk in France during World War II.

One of the accountants I wrote about in Inkwells to Email was Major Hugh Aiton Aitken Baird (1911-2000), from Hastings, who witnessed the Dunkirk events first-hand.

Hugh Baird left New Zealand in 1929 with his parents, who were on a trip to Scotland, to train as an accountant in England.

He had been planning after leaving school to study accounting at Otago University, but it was suggested by a family friend that he go to England (and travel with his parents) to study and work as an articled clerk.

This meant five years without any income because the position was unpaid.

Hugh was supported by an uncle in England who was a doctor, because no money could be sent then to the UK from New Zealand.

After Hugh qualified, he returned to New Zealand in 1935 and worked for a Wellington firm.

However, his former English accounting practice wanted him back.

He returned to England in 1936, and to his English fiancee, Phyllis, whom he married that year.

His life would soon be interrupted with the threat of war, and Hugh volunteered for the territorial British army in 1938.

He learned to ride horses and fire heavy artillery, with his rank being lance bombardier.

The call-up for service came in August 1939, and when war was declared in September he was sent to camp.

His first commission was in January 1940, and he received the rank second lieutenant.

After landing in Belgium, they faced the German army, using 18-pounder guns against them from World War I.

When his gun-position officer was killed, Hugh took over command of the artillery unit.

“The British army does not withdraw, it just adjusts its position.”

When a retreat was signalled, Hugh said: “The British army does not withdraw, it just adjusts its position.”

In the process of “adjusting its position”, his quad vehicle towing a gun took a wrong turn. They realised this just as they were about to head right into the Germans’ path.

Before this, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, or “Monty”, had told the retreating British to blow up their guns.

Hugh and his unit arrived on a Belgian beach which was not under attack. Dutch civilians were evacuating men three at a time by rowboats on to larger vessels.

Because this was slow, Hugh was asked to take 30 married men to Dunkirk for a faster evacuation.

What met him at Dunkirk he would describe as a “shambles”.

On the beach they were bombed and fired on, leaving Hugh to think he was better off at the Belgium beach – to which he returned, only to find it evacuated.

Hugh, as the most senior officer, faced a mutiny of sorts among the men he returned with, and pulled his revolver to encourage co-operation. When a Belgian boat arrived, an exhausted Hugh was carried on it by two soldiers.

Once back in England, just as in the movie Dunkirk, he was put on a train and given a cuppa and bread and butter, which tasted superb because in Belgium they’d had to kill farm animals and forage for food.

Hugh would receive a promotion and come across Monty again at an officers’ briefing, where Monty said to the men assembled: “During my talk there will not be any coughing. Absolute silence will exist. In a minute you will be given a chance to cough.”

What followed, recalled Hugh was inspirational, which concluded by Monty saying, “We will win.”

When the war ended in 1945, Hugh Baird had the tile [title] of Major.

He could have strong opinions, and took no nonsense. This was probably why, when I was sent as a 17-year-old accounting clerk at Ingram, Thompson and Berry to deliver him a file, partner Des Thompson told me not to give Major Baird any of my cheek.

When he settled back into life in New Zealand after the war, he began an accounting practice in Hastings, and served his community well. He was a Hastings city councillor from 1959-1971, and instrumental in forming the golf club at Flaxmere. His tenacity even saw him get Hastings weather temperatures recorded on television, after only Napier had been shown.

Other achievements were a push for the Hastings and Napier motorway, and being a prime mover in forming the community Trust Bank.

Former Trust Bank chief executive Ewing Robertson described him “as a man of great vision, who was not easily deterred.

When he took on a cause, Hugh did not back off when he knew he was right”.

After Hugh passed away in 2000, I interviewed Jackie Baird, Hugh’s wife, for information on his life. Jackie, since deceased, gave me an oral history conducted in 1996 by Alex Crockett [Crocket] with Hugh.

Michael Fowler ([email protected]) is a chartered accountant, speaker and writer of history

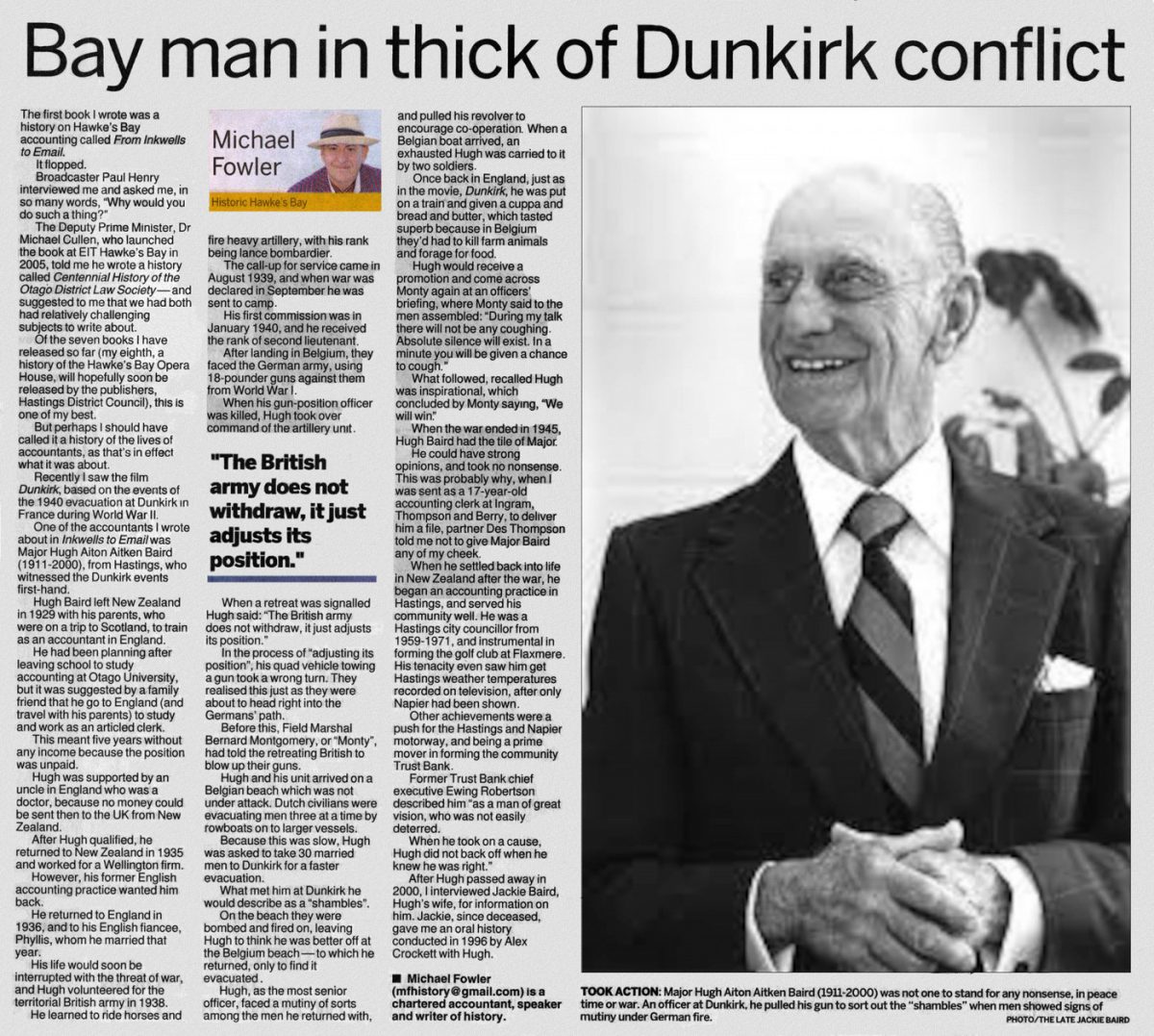

Photo caption – TOOK ACTION: Major Hugh Aiton Aitken Baird (1911-2000) was not one to stand for any nonsense, in peace time or war. An officer at Dunkirk, he pulled his gun to sort out the “shambles” when men showed signs of mutiny under German fire.

PHOTO/THE LATE JACKIE BAIRD

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.