The big wet of Anzac 1938

From day one, as in a German prisoner of war camp, which in little more that a year could hold Peanuts and his friend, the prime motive was to escape the Te Pohue pub and get home. Rain and thundering hill-sides never ceased for the first two days and nights, scary and menacing.

Our first official visit from the proprietor (Prop from now on) took the form of an address. Dressed in a navy suit for receiving guests, collarless shirt, brown hat and without his teeth, he didn’t ooze traditional hospitality. His mumblings included information on meals, hot baths, bar and behaviour (which I now suspect covered “goings on”, and were mostly unavailable or strictly rationed.

After a Council of War a diplomatic truce was put forward by our escape committee, and a roster drawn up for priority with firstly hot baths, sleeping arrangements and such. Some rugs were provided, pillows, even a hot water bottle and sheets to curtain off a corner for women’s privacy.

Lack of communication with the outside world was the worst frustration. We all sat round trying to get to know each other. There were some miserable faces. We were fed somehow, with what I forget, but we were informed bread was running low. The Te Pohue store helped all they could. It was possible to dash out and buy some biscuits for the children who were unnaturally quiet cooped up like that still dumb-struck by the total experience.

A sigh of relief went up when Prop opened the bar and he was almost smiling when he rattled the till. He had his teeth in by now. Sunday’s and Monday’s weather was slightly less vengeful than Saturday’s. Nerve-shaking to listen to at night but I had a pillow now and Mum was fixed up with a rug. There were some tears, shushing of children, comforting and even a few giggles in the dark. Tuesday morning brought some window light which lifted spirits somewhat. Then good news. Mr McKeesick of Rukumoana Station, some miles away, had fixed his private phone line and all were welcome to use it. The children and dogs almost exploded up the hill shouting and barking for joy. The devastation in front of the pub alone was a shattering sight, even to those of us who thought we’d seen it all – but not in daylight. Little Lake Te Pohue had merged with a huge mud crater that was once the road turning the bend to King’s orchard. When we reached the top of the first hill, by which time the rain had stopped, sun coming through, we could see even though the clouds hung over distant hills, mile after mile of devastation. Stark brown slopes, treeless except for an occasional stalwart clump clinging there.

Mrs McKeesick’s kitchen was so clean, warm and bright we scruffies were ashamed at first to enter. Children and dogs outside! The smell of hot scones made me reel with hunger. Mrs McKeesick must have been baking since dawn.

One by one we successfully got through on that crackling line, instructed by our kind hostess how to crank the handle. Mum got hold of Dad at work and that was the first time for days I had seen her really smile. Mid-week, a Gypsy Moth bi-plane barn-stormed the pub and had us all outside waving and cheering, watching for the food drop the men had arranged over the McKeesicks’ phone. The huge pack landed with an audible thump followed by several Red Cross parcels. The men raced for them and however squashed (no sliced bread then fortunately), bread was bread.

With more settled weather and drying mud, escape plans went ahead. I hiked over the hills with the deer hunters and was taught to use a .303.

Now Mum had more worries, but it was Peanuts (the only name I remember) and his mates who reconnoitred and planned our route cross country via Rissington to Napier. I had been invited to go with them. What excitement!

The night before they left, however I was asked by a school teacher (on Mu[…] guessed) to have a little chat – in the bathroom. We sat side by side on the edge of the bath while deeply embarrassed, I meekly listened to a type of “birds and bees” story, waiting for him to come to the point. I took the hint and stayed behind with Mum.

We could see even, though the clouds hung over distant hills, mile after mile of devastation.

On the appointed day, one week from our arrival, the full party set off in sunshine. The Fryers with their dogs took a more direct route down the Esk Valley, six feet deep in mud in places. We passed the Dampney’s Eland Station to reach our night stop, the Dole Camp where we were expected, the bush telegraph having been busy.

We shared their meal, sitting on long benches at scrubbed wooden tables, devouring heavenly mutton stew, spuds, onions and camp-oven bread.

Our host politely introduced us to washing and sleeping facilities, including the long-drop, to which Mum and I were no strangers. We topped-and-tailed on a single bunk. I kept my now stiff-as-a-board socks on. It was so cold, and one gray blanket did little to lift the mercury.

Welcome dawn and good hot porridge with mugs of strong tea. I learned that the workmen had shared bunks in order to give up their mattresses, other wise we’d have “slept” on wire-wove. We made our goodbyes with grateful thanks and were on our way, Jimmy with a large mutton shank.

The “road” was off-again-on-again with wearisome obstacles, but the bongo-drums were still active. At the junction of the Taupo Road with a back-country road to the west a man appeared on a horse (the late Michael White) carrying shearers’ billies of hot tea, and couple of 50lb flour bags full of hot buttered scones, from the nearby farm. Standing around on the road in the sun, farmers and their wives to talk to, it was more like an “al fresco” morning tea party.

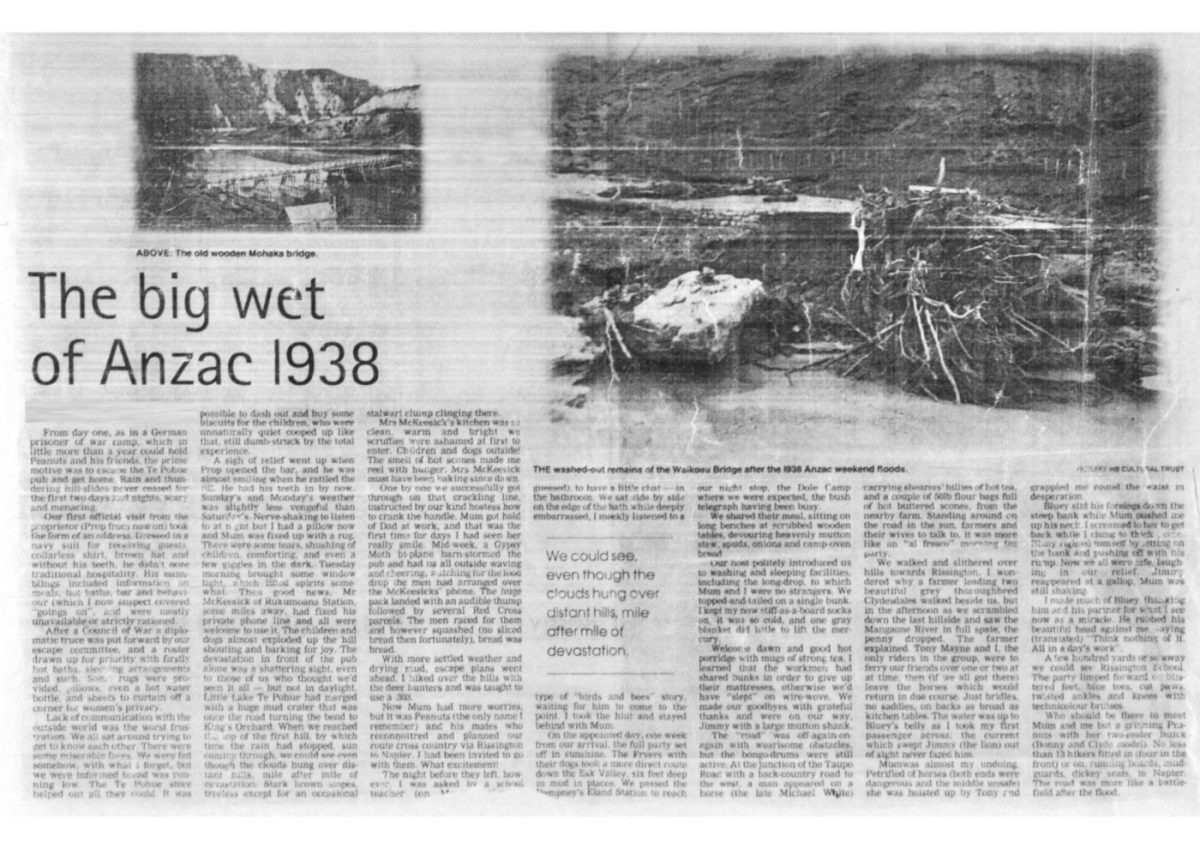

We walked and slithered over hills towards Rissington. I wondered why a farmer leading two beautiful grey thoroughbred Clydesdales walked beside us, but in the afternoon as we scrambled down the last hillside and saw the Mangaone River in full spate, the penny dropped. The farmer explained. Tony Mayne and I, the only riders in the group, were to ferry our friends over one or two at a time, then (if we all got there) leave the horses which would return in due course. Just bridles, no saddles, on backs as broad as kitchen tables. The water was up to Bluey’s belly as I took my first passenger across, the current which swept Jimmy (the lion) out of sight never fazed him.

Mum was almost my undoing. Petrified of horses (both ends were dangerous and the middle unsafe) she was hoisted up by Tony and grappled me round the waist in desperation.

Bluey slid his forelegs down the steep bank while Mum pushed me up his neck. I screamed to her to get back while I clung to thick mane. Bluey righted himself by sitting on the bank and pushing off with his rump. Now we were all safe, laughing in our relief. Jimmy appeared at a gallop. Mum was still shaking.

I made much of Bluey, thanking him and his partner for what I see now as a miracle. He rubbed his beautiful head against me, saying (translated) “Think nothing of it. All in a day’s work”.

A few hundred yards or so away we could see Rissington School. The party limped forward on blistered feet, cut paws, twisted ankles and knees with technicolour bruises.

Who should be there to meet Mum and me but a grinning Peanuts with her two-seater Buick (Bonny and Clyde model). No less than 13 hikers fitted in (four in the front) or on running boards, mud-guards, dickey seats, to Napier. The road was more like a battlefield after the flood.

Photo captions –

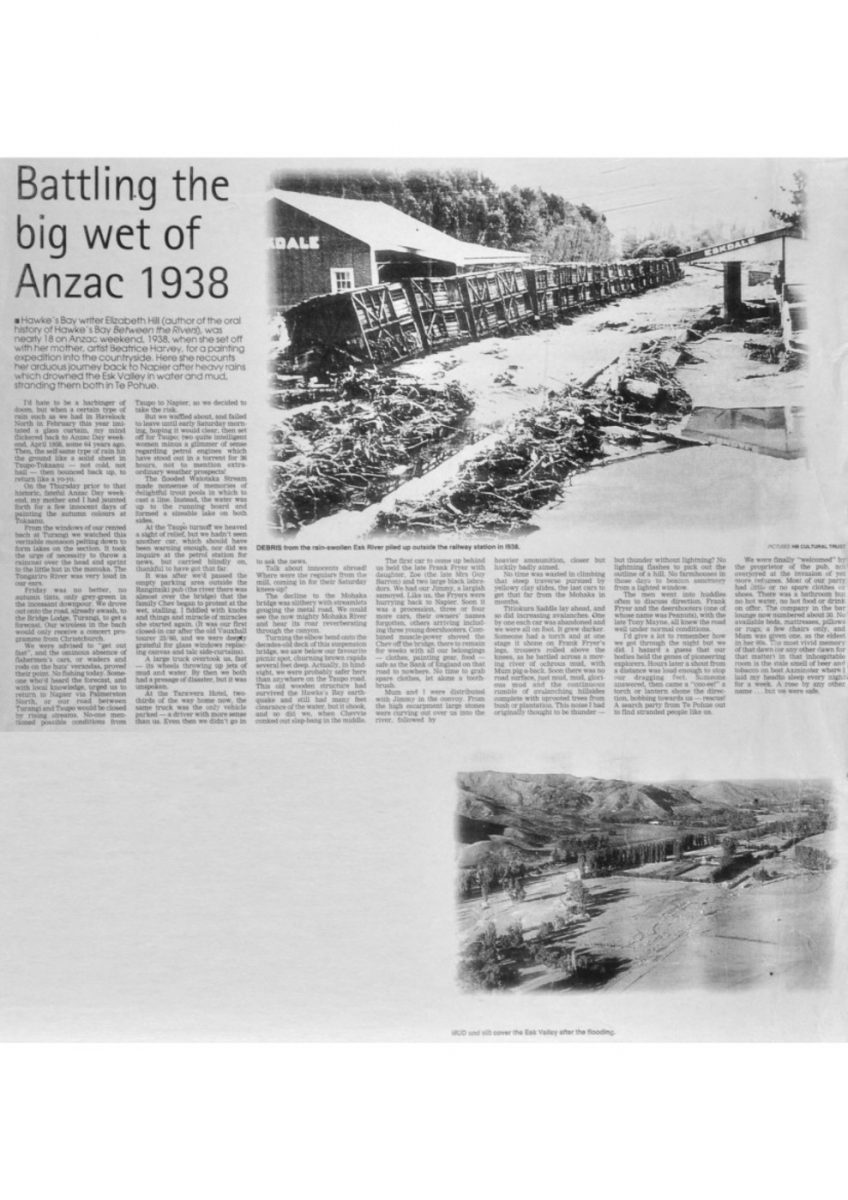

ABOVE: The old wooden Mohaka bridge.

THE washed-out remains of the Waikoau Bridge after the 1938 Anzac weekend floods.

PICTURES: HB CULTURAL TRUST

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.