Tomoana coopers to be phased out soon

Story by staff reporter MARY HOLLYWOOD

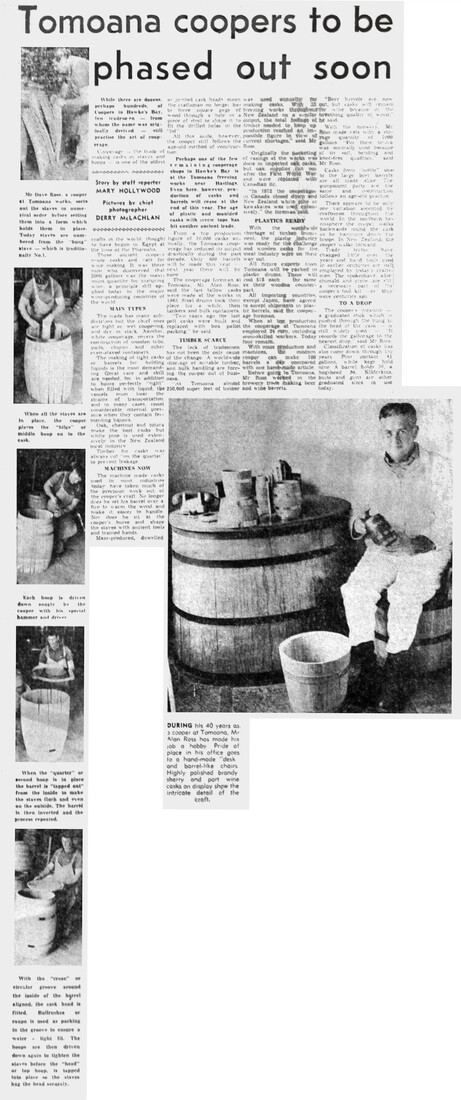

Pictures by chief photographer DERRY McLACHLAN

While there are dozens perhaps hundreds, of Coopers in Hawke’s Bay, few tradesmen – from whom the name was originally derived – still practise the art of cooperage.

Cooperage – the trade of making casks of staves and hoops – is one of the oldest crafts in the world, thought to have begun in Egypt at the time of the Pharoahs [Pharaohs].

These ancient coopers made casks and vats for wine making. It was these men who discovered that 2000 gallons was the maximum quantity for maturing wine, a principle still applied today in the major wine-producing countries of the world.

MAIN TYPES

The trade has many subdivisions, but the chief ones are tight or wet coopering, and dry or slack. Another, white cooperage, covers the construction of wooden tubs, pails, churns and other even-staved containers.

The making of tight casks or barrels for holding liquids is the most demanding. Great care and skill are needed, for in addition to being perfectly “tight” when filled with liquid, the vessels must bear the strains of transportation, and in many cases, resist considerable internal pressure when they contain fermenting liquors.

Oak, chestnut and totara make the best casks but white pine is used extensively in the New Zealand meat industry.

Timber for casks was always cut “on the quarter” to prevent leakage.

MACHINES NOW

The machine made casks used in most industries today have taken much of the precision work out of the cooper’s craft. No longer does he set his barrel over a fire to warm the wood and make it easier to handle. Nor does he sit at the cooper’s horse and shape the staves with ancient tools and trained hands.

Mass-produced, dowelled or jointed cask heads mean the craftsman no longer has to force square pegs of wood through a hole in a piece of steel to shape it to fit the drilled holes in the lid.

All this aside, however, the cooper still follows the age-old method of construction.

Perhaps one of the few remaining cooperage shops in Hawke’s Bay is at the Tomoana freezing works near Hastings. Even here, however, production of casks and barrels will cease at the end of this year. The age of plastic and moulded casks with screw tops has hit another ancient trade.

From a top production figure of 10,000 casks annually, the Tomoana cooperage has reduced its output drastically during the past decade. Only 400 barrels will be made this year – next year there will be none.

The cooperage foreman at Tomoana, Mr Alan Ross, said the last tallow casks were made at the works in 1963. Steel drums took their place for a while, then tankers and bulk containers.

“Two years ago the last pelt casks were built and replaced with box pallet packing.” he said.

TIMBER SCARCE

The lack of tradesmen has not been the only cause of the change. A worldwide shortage of suitable timber and bulk handling are forcing the cooper out of business.

“At Tomoana almost 230,000 super feet of timber was used annually for making casks. With 33 freezing works throughout New Zealand on a similar output, the total footage of timber needed to keep up production reached an impossible figure in view of current shortages” said Mr Ross.

“Originally the packeting of casings at the works was done in imported oak casks, but oak supplies ran out after the First World War and were replaced with Canadian fir.

In 1972 the cooperages in Canada closed down and New Zealand white pine or kawakatea [kahikatea] was used extensively,” the foreman said.

PLASTICS READY

With the worldwide shortage of timber imminent, the plastic industry was ready for the challenge and wooden casks for the meat industry were on their way out.

All future exports from Tomoana will be packed in plastic drums. These will cost $18 each – the same as their wooden counterpart.

All importing countries, except Japan, have agreed to accept shipments in plastic barrels, said the cooperage foreman.

When at top production the cooperage at Tomoana employed 24 men, including semi-skilled workers. Today four remain.

With mass production and machines, the modern cooper can make 100 barrels a day compared with one hand-made article.

Before going to Tomoana, Mr Ross worked in the brewery trade, making beer and wine barrels.

“Beer barrels are now out, but casks will remain for wine because of the breathing quality of wood,” he said.

With the brewery, Mr Ross made vats with a storage quantity of 1000 gallons. “For these totara wood was normally used because of its soft, bending and knot-free qualities,” said Mr Ross.

Casks from “bottle” size to the large beer barrels are all made alike. The component parts are the same and construction follows an age-old practice.

There appears to be only one variation accepted by craftsmen throughout the world. In the northern hemisphere the cooper walks backwards round the cask as he hammers down the hoops. In New Zealand, the cooper walks forward.

Trade terms have changed little over the years and hand tools used in earlier centuries are still employed by today’s craftsmen. The spokeshave, adze, chimald and croze are still a necessary part of the cooper’s tool kit – as they were centuries ago.

TO A DROP

The cooper’s measure – a graduated stick which is pushed through the bung to the head of the cask – is still widely used – “It records the gallonage to the nearest drop,” said Mr Ross.

Classification of casks has also come down through the years. Pins contain 4½ gallons, while kegs hold nine. A barrel holds 36, a hogshead 54. Kilderkins, butts and guns are other graduated sizes in use today.

Photo captions –

Mr Dave Ross, a cooper at Tomoana works, sorts out the staves in numerical order before setting them into a form which holds them in place. Today staves are numbered from the “bung” stave – which is traditionally No. 1.

When all the staves are in place, the cooper places the “bilge” or middle hoop on to the cask.

Each hoop is driven down snugly by the cooper with his special hammer and driver.

When the “quarter” or second hoop is in place the barrel is “tapped out” from the inside to make the staves flush and even on the outside. The barrel is then inverted and the process repeated.

With the “croze” or circular groove around the inside of the barrel aligned, the cask head is fitted. Bullrushes or raupo is used as packing in the groove to ensure a water-tight fit. The hoops are then driven down again to tighten the staves before the “head” or top hoop is tapped into place so the staves hug the head securely.

DURING his 40 years as a cooper at Tomoana, Mr Alan Ross has made his job a hobby. Pride of place in his office goes to a hand-made “desk” and barrel-like chairs. Highly polished brandy, sherry and port wine casks on display show the intricate detail of the craft.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.