- Home

- Collections

- MOODY M

- Newspaper Articles

- Newspaper Article 1996 - The making of a man

Newspaper Article 1996 – The making of a man

The making of a man

Woody Collins is dying of leukaemia. He faces death the way he has faced life – straight in the eye without flinching. It is the measure of a man, he reckons, the manner in which he dies.

It is not the first time Woody has faced death; once buried under a slip while driving roads into the heart of bushland on the Taupo road, or the time he was rescued by a US soldier, or the time he and two others faced a pack of wild dogs that once roamed the ranges of the Central North Island. More than once he has looked down the barrel of a gun or felt the hairs on the back of his neck prickle with the knowledge that a rifle scope has him in its sights. They are stories that Woody does not divulge easily: he does not want to glorify his life, nor appear arrogant. He has known many men he ranks ahead of himself who have carried out great feats and never uttered a word of their travels or travails. They taught him humility. Talk to others who knew Woody and many mark him down as a “great man.” Such talk would certainly embarrass him. Upon the first meeting to interview Woody he surveys, measures, talks straight and jokes that no one would want to hear his story. But he is one of the characters of Hawke’s Bay and indeed, New Zealand, who have worked back-breakingly hard to secure their place and provide for their children. Says Woody: “Half the people have not lived who have made the journey.” His journey from his early days in Central Hawke’s Bay is unique, full of rich memories of the region in the past three score and ten. He came highly recommended as a character and his stories do not disappoint. In the first of a series, The Sun’s Doug Banks talks to a man who helped shape the region.

Woody Collins is a fighter, descended from a long line of fighters, some of whom had reportedly fought in Europe as mercenaries before embarking to the Antipodes early last century.

Woody’s Mum, Laura Collins, had recognised a propensity to find conflcit [conflict] in her boy at an early age and knew he would find the fighting fields just like his ancestors.

“You won’t be at peace until you’re in the grave.” Woody remembers her saying.

Woody’s father had died of cancer soon after Woody and his brother were packed off to Havelock North’s Hereworth School.

When he returned home to Homewood Station from Christ’s College in Canterbury as a 15-year-old, Laura Collins continued the process of “standing up” her boys, Woody and Peter.

Laura Collins was a feisty woman in her own right (she once told Woody how to work up and down a man’s ribs to ensure his opponent would remember him for two weeks after a fight), and she knew the boys needed the firm guiding hand of a man, so Woody was sent to work alongside one of the farm labourers, a bushman by the name of Jim Halcrow, now into his seventies. He was to play a big part in shaping Woody the man.

“My cunning mother sent me to work with him; it was no coincidence. Teach the boy, she had said to him.”

Halcrow – Woody’s voice deepens and rasps with respect when he says his name – had been a sailor in the South China Sea for 20 years before jumping ship in New Zealand, picking up any work he could before settling on Homewood Station. Halcrow was not his real name. The laws of the day had meant that Halcrow was still a fugitive and Laura Collins complained to her local MP, Cyril Harker.

“Me Mum said to Cyril Harker: ‘Cyril this is disgraceful. This man has been in New Zealand 20 years and can’t get a pension. He’s 76 and still splittin’ posts.’

“And Cyril says: ‘Laura, that’s against the law of the land.’

“I don’t give a bugger Cyril. You’re in Parliament, attend to it.”

“Next week, damn the law; the law of the land went out the door.”

It was the autumn of 1936, on a Monday, when Woody was sent down to work with Halcrow after gathering a list of gear provided by his mother – hooks and shackles, axes and saws. Woody loaded the farm’s crawler tractor and headed for plantations, planted by his grandfather James to stop the Waipawa River (now known as the Papanui), bringing the metal over its banks on to the farm.

The loggers split battens out of the heads of the silver poplar and the logs all went to the mill.

“I arrived down the back with the tractor, saw, axes, wedges and things. He looked me up and down for about five minutes; just stood there. Course, he had this great bloody walrus beard, moustache, pants curled over at the ends. He always wore bo-yangs, no socks.

“We went over to this tree to come down, a poplar and he pulled out a blunt saw. Unbeknown to me, the bloody head shepherd had told him I was the laziest bastard on the place. Course, I’d never pulled a cross cut in my life. A great big bloody six-foot-six saw … and I’m rubbin’ away and I don’t know how to use the damn thing; and he lets me go wanted to test whether I’d squeal.

“My shoulders were achin’… these teeth wanted sharpenin’ and settin’… it wasn’t cuttin’… it was tearin’ the arms out o’ me… and he knew that and he disappeared for a while. My young shoulders just kept achin’.

“By then, I was sawin’ all to hell. He knew and y’know, he never said a word. Then all of a sudden, he puts in this cut and chopped the scarf out and we went round the back. They used to stick the axe in to hold the saw up, y’see.

“I’d cut three parts through… three quarters of an hour non stop. And the old bastard, the saw stopped in the cut just like the brake went on, and he came round and said: “Oooh Wood, I think we earned a spell.

“From that day on, I was his man.”

Woody says it was an honour to work with Halcrow.

“Halcrow knew all the pulling hitches, tackles; no winch. These buggers never learned physics, they used blocks and tackles, pulleys, snatch blocks. The amazing thing about logging, if the weight is alive, if you’re breaking out a log like that, you always pull a half lift on it so the log lifts and then rolls; it’s alive, away it’ll go. If you try to lift it dead, it’ll break the gear. Pulling a rolling hitch so the log would keep spiralling. I still marvel at physics, I really do. What got me, some enormous logs we pulled out, some up to 25 tonnes. Wouldn’t break that strop, because the log was alive, we got it moving. Then we’d snipe and dee it. Today that [they] do it with a chainsaw.

“There’s a knack in all this. The old man taught me, how to use the axe, how to dress them up.

We’d get one each side of the tree, no good if you’re only right handed. I’d be messing it up with the left hand, and he’d come round and straighten it up. Go on Wood keep going, He’d teach you. If there was a shiner (a loose limb) in the tree, he knew which way they’d come down. If you didn’t watch them, they’d get you.

“One day I pointed up to him and said. ‘Jim there’s a shiner up there,’ and he grinned. I told him I’m young and I can get out of the way quicker than you, you’re old. He grins again and I can see he’s thinking, ‘young bugger’s gonna look after me now.’ But he looks at me hard and he says, with his voice deepening” ‘Get on the other side Wood. I’m old; my time is finished, you’ve got a long trail to the other side.”

“He also had a responsibility to my mother you see.

“Finish, no arguing. If somebody’s to die, better for me, I’m at the end life. These guys are real men, gutsy bastards, what a pleasure to work with.

“I worked for this guy for four and a half months. He chased Frank Smith out of the bush. Called him a Pomeranian bastard. He could throw an axe, lay it in like that (Woody waves his hand in an arc to illustrate its path) and never break the handle.”

One day, the young Woody was sitting playing with his knife quietly when Halcrow leaned over and said: “I’ll show you how to throw.”

“I was fascinated. He could throw a marlon spike (a long tapered punch) over and over for 50 metres and land it where he wanted. All those years in the China sea. He knew how to fight and look after yourself.”

Woody and Halcrow even fought together at times.

On one occasion, one of the farm workers talked ill of Woody, with which Halcrow simply threw him over his shoulder, pounced on him, whipped out his knife and pricked the tip into his neck, drawing blood.

“I won’t hear ill of Wood” he growled.

Woody says they would go straight through the river and work for six weeks and after finishing work Halcrow would have a “drunk up for five days… whisky and beer chasers.”

“He used to say to me, ‘Wood, the undoing of me has been Johnny Walker and Mrs Speights.’

“When he left us, he went down to one of those whares down the river by Waipuk [Waipukurau]; an old man’s shack.

“Then one day, Mum went to the Napier hospital to visit a friend and there’s this old man, wizened up old bugger, skinny and stickin’ out of the sheets. God she was aghast. he’d been such a well-built man, not gigantic. Y’ know, a very well-made man.

‘What’re you doin’ here?, Mum had said.

‘Ooh Madam” (he always caller [called] her madam) I’m dyin.’

“Then he said, ‘don’t put me in a pauper’s grave,’ and Mum didn’t. She took him back home and buried him and put a stone on him.”

Halcrow was just one of the many people and the logging just one of the events that spurred Woody to live life as most could never have.

Photo captions –

Bush work in those days

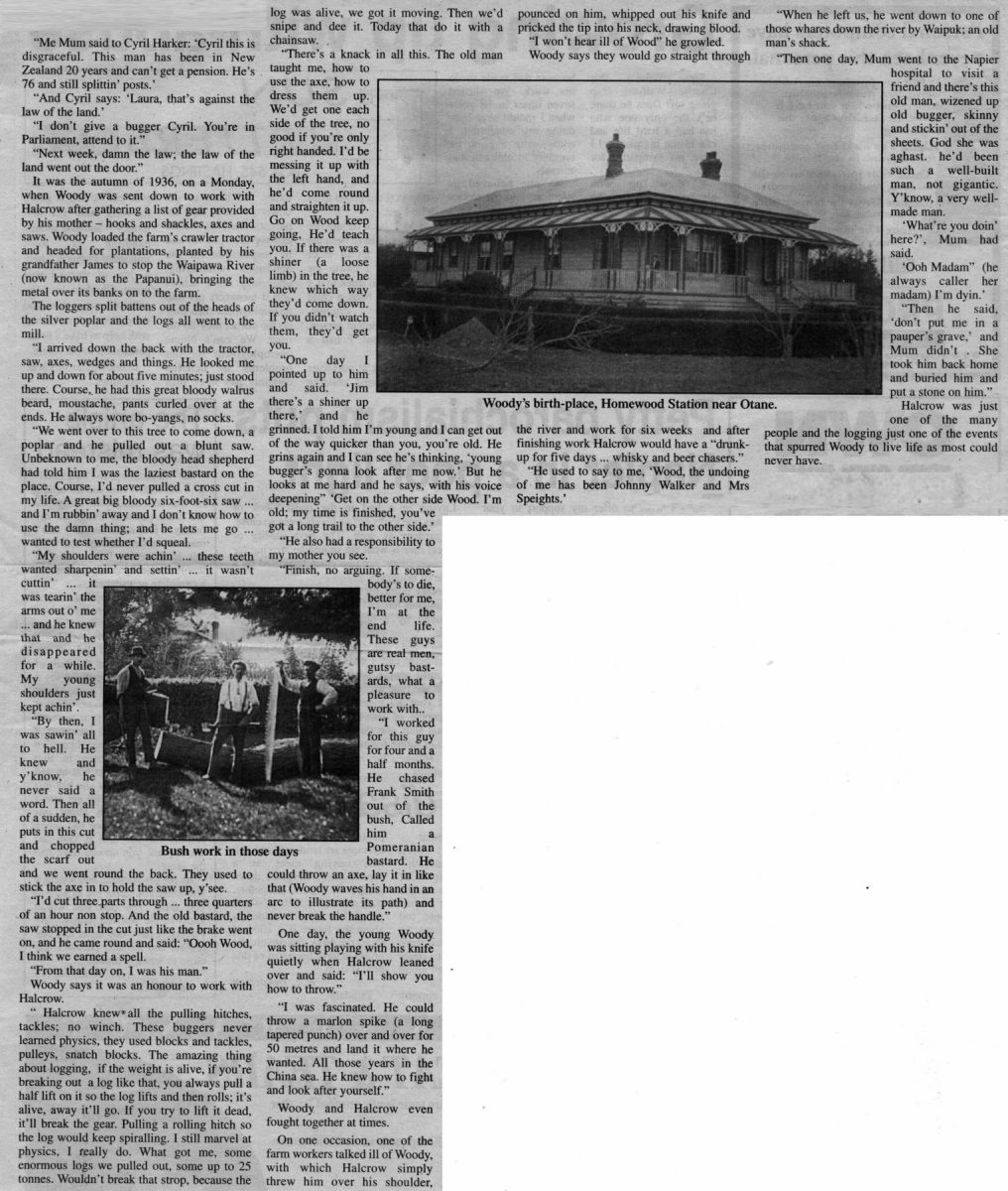

Woody’s birth-place, Homewood Station near Otane.

HB pioneers

This is the second part in a look at the life of Woody Collins, a member of one of Hawke’s Bay’s pioneering families and a man who was a pioneer in his own right, living a remarkable life in which the unusual became an everyday event. Today, The Sun looks at the early Collin’s family arrival in the region.

Like most settler families whose history is clouded by the mists of time, the circumstances surrounding the Collins emigration from England to New Zealand are not 100 per cent clear. Woody says that brothers Samuel and Edward Collins and their families, the original Collins pioneers in Central Hawke’s Bay, first arrived in Australia about 1840 or just before. A newspaper cutting floating round the family shows that when the ship docked at Sydney, the newspaper reporters, as was the custom, checked all the new arrivals as they departed from the ship.

For some reason, the brothers were not on the passenger list of the ship but were recorded in the newspaper. After scouting Australia as a possible destination, Edward and Samuel Collins, travelled to New Zealand, landing in Hawke’s Bay.

They were transported up the Tukituki River in Maori war canoes loaded with their belongings and supplies. The river, which was the main transport route into the hinterland by barge, pulled in the narrows by horse, was much deeper then and was still bordered by bush and scrub. The development of open pasture that eventually caused the river to widen and become shallower as it is today had not yet started.

All along the Tukituki’s course to Patangata, Woody can point out the rifle pits on the brows of the hills where the militia defended the river to keep it open. Woody has drawn crude maps for his family showing the pa sites, urupa (burial grounds) and other historic sites.

Samuel Collins, whose blood spawned the Collins clan in Hawke’s Bay, took a small piece of land overlooking the river near Patangata where he built a small slab totara cabin. It has long since gone but the signs of the orchard he planted still remain near the junction of the Otane-Patangata Road where it joins Valley Road.

Samuel’s brother, Edward, took over Tamumu Station, developing his block quickly. His earliest stock returns were recorded in 1854. He soon sold Tamumu and bought Abbotsford Station near Waipawa, but again sold and headed to Australia. In his time in Hawke’s Bay, Edward served in the colonial militia at the Ruataniwha and Waipawa stockades in the first Hau Hau uprising. At the time that Samuel and his brother were breaking in the land near Otane, Woody says that some of the Collins’ descendants had liaisons with the local Maori women, whose menfolk had been decimated in fighting during the Hau Hau uprising and beyond. There were five pa in the Patangata area. Most had 30 women to every man as a result of the devastation wrought by the musket wars. These wars were Maori against Maori, not the land wars that were to follow.

One of Samuel Collins’ boys, Reuben, was apparently packed off to Woodville because of these liaisons. Woody says the Maori name Karena is a derivative of Collins, taken by the offspring. He has a vivid childhood recollection of driving near Te Hauke with his father past a group of local Maori who, upon seeing A.V. Collins, turned and put their arms in the air and chanted “Karena”. Woody also reckons these liaisons with the Maori in the area were to help the Collins in the wars that followed, with the family forewarned when raids were planned. Sometimes, Woody says the Maori warriors would stay with the family in case a raiding party turned up. Both Samuel and his brother Edward spoke fluent Maori.

This bond between races was cemented, he says, during the clearing of the land, the shearing of the sheep and the myriad of other jobs as the properties were developed. “My ancestors were fortunate to have these brown allies on the back door, like an extended family.’ Samuel had seven children by two wives, but his son James was to go on to be the driving force to develop the Collins land. James, by all accounts an unusual man who, like Woody, couldn’t resist the scent of a fight, bought more land near his father and eventually developed the estate, Homewood Station, to some 12,000 acres. James fought at the battle of Omarunui in 1866. One of Woody’s sons still owns the muzzle loader complete with matching bayonet and serial number from that battle. The bayonet is slightly shorter than normal because it was later used for a period as a pithing spike at Homewood’s abattoir. Because there were no stud associations at this stage, James sent his sheep to Australia to his Uncle Edward Collins for sale.

The original homestead James built was burned down, by locals who believed the homestead haunted, and the present homestead, Homewood was built.

James became a local councillor, was a member of the catchment board, helped establish the Otane Saleyard Company, which was a major saleyard in those days and helped to get a Post Office at Otane.

James’ penchant to have it out with opponents was legendary. Woody tells the story of Alfred Dillon, who had been a bullockee, (a bullock driver), carting the wool and goods in Central Hawke’s Bay when there were no real roads to speak of and the bullocks could negotiate the mud. Dillon was to write home to a newspaper in England later that during his bullock work he spied this beautiful woman, Rebecca Collins, in the Tukituki Valley, and decided he would marry her.

With the marriage went a dowry of Collins sheep and land above the Patangata Hotel. Dillon later stood and gained a seat in Parliament for the Seddon Government. Woody says he was known to drink heavily and had to be thrown out of Parliament on occasions. He became known as the Dick Whittington of New Zealand politics.

Photo caption – Woody at grandfather James’s grave.

Fighting it out

The Sun has been overwhelmed with requests for more stories on Hawke’s Bay pioneer Woody Collins, a man who has lived life to the full, from his days in Central Hawke’s Bay’s Homewood Station, to developing his own landholdings including a 1900-acre farm on the Napier/Taupo road. Woody has little time for the do-gooders of today who bemoan the presence of guns in our society, the lifting a hand to children for discipline or the art of self- defence. Today, the Sun’s Doug Banks talks to Woody about his love of boxing and some more of the hard cases he met in his travels.

Woody Collins’s mother, Laura, accepted early that her boy would attract trouble and put him with men who could teach him the ropes. Woody also recognised early his feisty nature and started boxing while at Hereworth School in Havelock North.

“One of the Ormonds was team coach… had been an Oxford blue or some damn thing.”

Woody fought at Hereworth, at Christ’s College and in his regiment in the Army. Although not a southpaw, Woody liked to be able to “come off either hand” but his left hand was not as good as it should have been.

“Clarke Orr beat me for a trophy. I couldn’t KO him. I knocked him down three times but my left hand was not powerful enough. I loved any contact stuff. Rugby, fightin’, crazy I suppose.

“I still get excited watching boxing. I won a lot of trophies but I didn’t always win. Each year I’d make the finals, though.”

By nature, what used to be his biggest problem in the ring was he wouldn’t cover up and defend as he should have.

“I always thought that was a cur. I’d bow and scrape to no man. If I did it again, I would cover up.”

The last time Woody fought in the ring was for the Army.

“I got all excited watchin’ and couldn’t contain myself. They’d brought some guys up from Wellington. They were one short from my regiment and they asked if anybody watching could match this bloke.

“Well, I was all wound up and I said I’d jump in. I hadn’t been in the ring for two years and was unfit. My mate Darcy Weekes had had a go and he went down three or four times, blood running out of his mouth and nose, and so I said ‘I’ll fight him.’

“I got in there and in two minutes knew I was in trouble… no training. I couldn’t hold my hands up to protect my face. I couldn’t even pull my gloves off at the end.”

Woody has taught all his seven boys – and his daughter – to handle themselves. His wife Rai had no objection.

“She was no-nonsense, strong like her father, a female amazon. Her father was frightened of no man.

Other women, Woody says, would ask Rai why she let him teach the boys to fight.

“Rai used to answer them by saying: ‘I have a family of seven sons. With sons, I don’t know where their feet are going to carry them. He’s teaching them to defend themselves’.

And Woody agrees; he thinks all boys should know how to save their own hide.

“I’d get the boys on my knees and show them how to box. I showed them how to defend themselves from a knife attack.

“George has got these knife marks up the inside of his arm where this kid went to work on him in Queen Street in Auckland.

“He knew how to deflect the knife so it went up his arm and not across where it would have cut his artery and nearly bloody killed him. That knowledge probably saved his life. It was my job to teach them the use of weapons. Thank God I had a wife that had the sense to know violence is everywhere in society, even today. I have never met a man in my life who didn’t understand a good hiding.”

Discipline was also no-nonsense in the Collins household. It had to be, in the mountains of Taupo where the boys would roam wild; they had to know the limits placed by the land.

For example, Woody remembers coming home after a day out fencing on Wainui and the house was as quiet as a a morgue.

Rai marched the children out and said: “Tell your father what you did.”

Being normal children, Woody says that none of them would “talka de English.”

Woody soon fiound [found] out that the older boys had put one of the boys, Custer, into a crack in the ground before the waterfall at the Waiotahuna River. The crack went into the ground to the river, went underground for 20 feet before it re-emerged.

“The boys had put Custer in and he shoots out over rocks at the bottom. The boys wanted to see how fast he’d run out the other end. Custer was only seven or eight.”

I lined ’em up, give ‘em all a hiding, bar the little ones. Next thing they’re all over by the trees going crook at one another about whose idea it had been.

“Do-gooders today say you don’t hit kids. I had to stop that nonsense or one of the kids would “a drowned.”

The tough upbringing also flowed over to their ability to handle pain.

Woody remembers Norman Fippard, a prominent man in Hawke’s Bay, telling him a story about Woody’s youngest boy.

He had been at the Fippards playing and he walked over to ask Mr Fippard if he had a pair of pliers. “What to do?” Mr Fippard asked.

“I’ve got a splinter gone up in my toenail,” he replied. A piece of kanuka gone up under his big toenail. It was as long as a match.

“Fippard said to me: ‘Do you know, that boy stood there, the splinter had gone right through the quick and he didn’t drop a tear. If that was one of my boys, he would have gone mad.’ You see, they were so well trained by their mother, not to pull away, to put their hand up and not flinch.

I’ve seen people rip their hand away when they’re about to be stitched. That first stitch is the most important one. Once ripped it will take twice as long to heal.”

Woody also remembers many other characters over the years who, like himself, loved to mix it and not bow to anyone; one was from the well-known Lowry family of Hawke’s Bay.

“We used to go down to the old pub down on the Rangitaiki, the old armed constabulary, it burnt down. This Ralph Lowry had bought Lochinver [Lochinvar] Station.

“Ralph talks very good English. He’s been educated at Oxford, not la de da, just the Queen’s English. Ralph is a bloody tough man. He is not what people think he was. He fought in the Afghan war, in the Coldstream Guards, in England. Each one did their time.

“At Rangataiki there was always a king hitter in the place. At that time, it was Snowy Stanfield. He was about a number 8 build of a bloke, a bushman, Pakeha joker.

“It was packed this night and Snow kept taking the mickey out of Ralph Lowry, saying things like: ‘Ooh, by Joves, old fellow, this and that.’

“All of a sudden, Lowry got his glass, spun it down the bar and he says: You know something Stanfield, you got a big mouth. Come and put your fist where your mouth is.

“The whole bar went quiet. “I laughed, because I knew this Ralph Lowry. He was a big bugger, over six feet and he walked, loping along. But unlike all those guys that lope around, Ralph picks things up with his left or his right. Those sort of guys can come at you with both hands. Dangerous buggers.

“Stanfield was half full of booze and goes down to Lowry thinking this is gonna be easy.

“I laughed. We used to love this, entertainment, better than television. Stanfield went to hit Lowry and Lowry brushed it aside with his hand and next thing Lowry hit Stanfield, one two three and I laughed. You read in westerns about how guys’ legs won’t hold them up. That’s exactly how this guy went…. blood ran down his nose all of a sudden, out of the sides of his mouth and he haemorrhaged in the eyes, which was unusual, and all of a sudden, his 17 stones wouldn’t hold him on his pins and he slid down in a pool of his own blood. Lowry looks around and says to the bar, all of them hard men: ‘Any more of you got any ideas, step up no’.”

There were no takers.

Later on at the Rangitaiki, Woody remembers his mate Tom Woods, who came along a few months later, a pushing boss in the forest for Sam Andrews.

“Tom’s built like Bill Bush, straight out from here (Woody draws a vee out from his hips). This is the best (hit) I’ve seen in my life and I’m a boxer.”

“Tom is real solid, 17.5 stone, and arms… go under a horse and hold a horse up. Punchy Wallace was the king hitter at this stage. Punchy had been a “punch ball” for the great New Zealand boxing brothers the Sands.

“He was punch drunk. When he was riding on the tram he used to hear the tram bells and want to get up and fight.

On this day, Punchy sees Tom Woods, the new bush foreman for Andrews’ gang, and decides he is gonna take him on. “Tommy – he’s up in the Mokai cemetery now – is there that night and Punchy hops up to him to king hit him and Tommy’s awake to him and he says ‘OK have a go’.

“Punchy goes to hit him and he misses. Tom didn’t. All of his 16 or 17 stone went into one hand and he he hit that man. As true as I sit here, that punch picked him up off the ground, he hit the bar door, the door went off the bloody hinges and out he went. Best bloody hit I’ve ever seen in my life. It picked him up and threw him through the air like a sheaf of wheat.

“Tom popped out to finish him off, but Punchy had only one thing on his mind; he didn’t want any more of that. Tom chased him three times round the pub, a frosty night, before he disappeared into the scrub.

“I always used to say to Wallace: ‘I met your mate the other day… Tom Woods,’ and he’d change the subject. Anybody else and he’d have said: “Wait till I see that bastard.” Woody Collins reckons he met many good men during his life – as well as bad – that’s another story…

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Tags

Format of the original

Newspaper articlesDate published

1, 15, 29 August 1996Creator / Author

- Doug Banks

Publisher

Hawke's Bay SunPeople

- Sam Andrews

- Custer Collins

- Edward Collins

- George Collins

- James Collins

- Laura Collins

- Rai Collins

- Rebecca Collins

- Reuben Collins

- Samuel Collins

- Woody Collins

- Alfred Dillon

- Norman Fippard

- Jim Halcrow

- Cyril Harker

- Ralph Lowry

- Clarke Orr

- Frank Smith

- Snowy Stanfield

- Punchy Wallace

- Darcy Weekes

- Tom Woods

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.