- Home

- Collections

- Tairawhiti Museum

- Nga Taonga O Tamatea

Nga Taonga O Tamatea

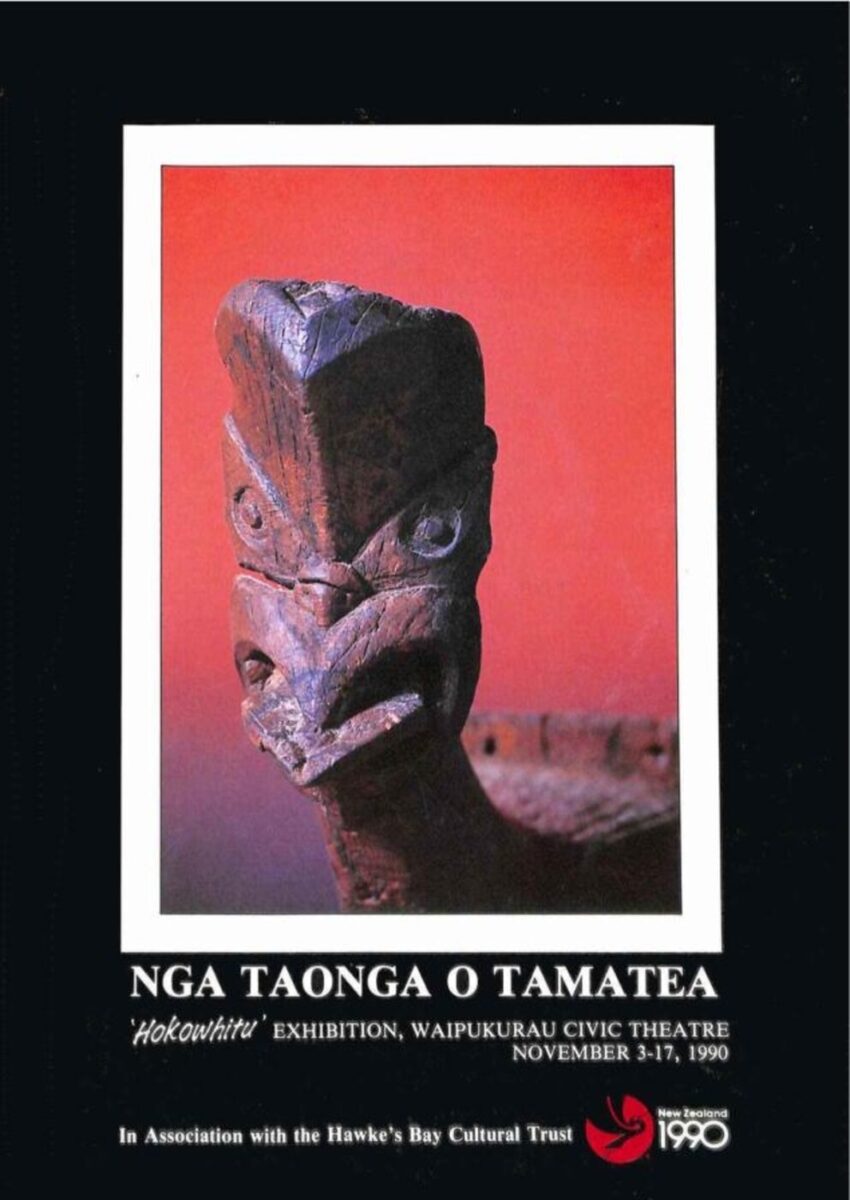

Cover description.

Tete (prow) of a fishing canoe (waka tete), found at Pariwhakaruru, Porangahau. Waka tete were used for short voyages along the coast and for fishing expeditions. The carving is of East Coast/Ngati Kahungunu style and dates probably from the mid-19th century. The decoration on the flat part behind the broken splash board is an extra embellishment.

Page 1

NGA TAONGA BOARD OF TRUSTEES

D. Tipene, Porangahau – Chairperson

P. Hira, Porangahau – Secretary/Registrar

D. Petersen, Waipukurau – Treasurer

D. Power, Pongaroa

A. Nation, Pourerere

T. Wilder, Elsthorpe

B. Hales, Wimbledon

CO-OPTED MEMBERS

Roger Smith, Director Hawke’s Bay Cultural Trust

Chris Arvidson-Smith, Registrar Napier Museum

Tony Kearns, National Museum

SCHOOL CO-ORDINATORS

Doug Putaranui

Brian Hales

LOGO DESIGNER

Don Stevenson

PHOTOGRAPHER

Grant Shanley

Page 2

TE RUNANGANUI O NGATI KAHUNGUNU INC

HE WHAKAOHONGA HOU

Ka ngaro mauri taonga ki Paerau

Kihai ka mau ki taiao

E te Iwi koutou i roto i nga mahi kua mahia e tatou i tenei tau. Ngati Kere i runga ia koutou nga taumahatanga o te waka. Ta tatou haere ki Waitangi i tutuki pai. Inaianei, ko te whakaatu i nga taonga a ratou ma kua mene atu ki te po. E te iramutu tena koe me o whakaaro Rangatira, e tautokotia nei e o tatou whanaunga Pakeha. Ka nui te mihi ki a koe.

A NEW AWAKENING

Mana taonga shall be lost to Paerau

If we do not uphold them.

To our Pakeha friends who helped us in all our projects, namely the waka, our visit to Waitangi, and now this exhibition of Maori Artefacts. I have no compunction in saying through your support a new awakening has happened to our Maori people to those things left by their ancestors. To thank you individually is not proper, but it is proper to thank our Rangatira. E Hugh Tena Koe.

Na ta koutou Pononga

CT Hohi

Charles Tohara Mohi

Page 3

PIPIRI HONONGA MAREIKURA

Poutokitangata found on the sea bed at Blackhead and named by Wi Te Tau Huata. It was used by Tohara Mohi to take the first chips out of the totara log, Te Ahurangi. Te Ahurangi formed the main part of the Ngati Kahungunu waka, Tamatea Arikinui te waka o Takitimu.

“Nga Tohara Te Ki! Pipiri Hononga Mareikura e ngau!”

Page 4

E TE RANGATIRA, A HOKOWHITU, HAERE E TE HOA,

HAERE KOE KIA RATOU KUA MENE ATU KI TE PO,

NO REIRA, HAERE, HAERE.

Nga Taonga O Tamatea ‘Hokowhitu’ Exhibition culminates many months of research compiling and collecting. It has also been one of the most enjoyable, challenging and rewarding experiences we have encountered. To the many nga people, libraries and museums who have played a part in allowing these treasures to be shared, to gain knowledge from, to enjoy, to respect and understand, on behalf of my fellow trustees, Nga Mihi Nui, Nga Mihi Aroha Kia Koutou.

In bringing together Nga Taonga O Tamatea, we have had a great experience of looking at our land, our people, our history and our future.

It is with confidence that I acknowledge the Taonga of our Tupuna is not a selection of artefacts of a culture that has passed, Nga Taonga is the link that binds us to our tupuna and leads us to our future and lives within us all today. 1990 is all about unity and understanding each others cultures I feel that this exhibition will bring us one step closer to achieving this goal.

There are two questions I often get asked, “Where is the correct place for these Taonga? And who are the rightful owners?” … For me at this point in time, from what I have seen, from the people I have met, they are safe where they are. For the future, they should be in a Whare Taonga within the tribal boundaries from where they came from, so we can all enjoy and give them the life and respect that they rightfully demand. Who are the correct owners of Taonga Maori? I believe Nga Taonga O Aotearoa belong to all the people of Aotearoa but first and foremost they belonged to the Maori.

Through the dedication and commitment of us all in Tamatea, we are a step ahead in the caring of our Taonga. These questions asked can only be answered by us all, but before the twenty-first century, they must be answered, so we can uphold the mana of our Taonga and our people.

I welcome you to come and enjoy, learn and listen.

NO REIRA

E TE IWI NAU MAI HAERE MAI.

CHAIRMAN, NGA TAONGA O TAMATEA.

RANGITANE DONALD KAKAHO TIPENE.

‘HE MOEMOEA

TA TENA TA TENA

KUA AEA TAKU’

Page 6

‘WELCOME’

It is a privilege to welcome Nga Taonga O Tamatea to the Civic Theatre, Waipukurau and to the Central Hawke’s Bay District.

This is a very special event; not only for those who have organised it but also for the whole of our community. A large number of visitors will be drawn to the exhibition and many will have travelled long distances to do so. I welcome you all.

I believe that, for our district, Nga Taonga O Tamatea will be remembered as the premiere event of 1990 as we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Waitangi and the founding of our nation. There are a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, the exhibition itself is unique. Many of the artefacts are displayed in public for the first time and others, whilst having been seen in museums and collections in other parts of New Zealand, they are gathered here together for the first time as a truly representative display of the most treasured and respect taonga of our ancestors.

Secondly, it has required an enormous amount of skill, dedication and sheer hard work on the part of the trustees and organisers of the exhibition to achieve this remarkable result and I congratulate them for their efforts. The outcome is something which they can all be proud of.

Lastly, while this important year has been celebrated throughout Central Hawke’s Bay in a wide variety of ways, it would be difficult to find an event which more aptly represents all the themes of 1990. This exhibition gives us the opportunity to reflect on the past, to learn from the art and culture of our forebears and to go forward as a community with pride and a positive outlook.

On behalf of the District Council and the resident of Central Hawke’s Bay, it is my pleasure to extend a warm welcome to everybody.

HUGH HAMILTON

Mayor

Central Hawke’s Bay District Council.

HAWKE’S BAY CULTURAL TRUST

The Hawke’s Bay Cultural Trust is proud to be able to assist with the Nga Taonga O Tamatea exhibition. We see our involvement as a reinforcement of our commitment to community outreach activities for the region. Particularly gratifying to us is that many of the taonga from our collection are being shown to the general public in Central Hawke’s Bay for the very first time.

Nga Taonga O Tamatea is more than just another exhibition; it is a statement of the past and the present; a project brought to fruition through the dedication of a few, for the benefit of many.

I Te Titiro Matou Ki Nga Wa O Mua

Ka Kapua Mai Nga Taonga

Mo Nga Ra O Mua Nei,

I Roto I Nga Taonga, Ka Mohia Matou

I Nga Tikanga,

Me Te Ataahuatanga O Nga Taonga Nei.

Roger Smith

Executive Director

Ruawharo Ta-u-Rangi

Hawke’s Bay Cultural Trust

Page 7

HOKOWHITU

NGA TAONGA O TAMATEA

The district of Tamatea has seen many people come and go. They have left behind them the evidence of their time, a variety of artefacts. Some lost, some discarded and left; and others, treasured, valued and carefully handed on from one generation to the next. These “taonga”, gathered together for this exhibition, help us trace the footsteps of our ancestors. For it is here that we, their descendants, still live, from Kairakau to Akitio, from the deep sea fishing grounds of the coast to the forest and snow-capped mountains of the Ruahine Ranges.

TE AO MATARAHI

There have been many ancestors and migrations of note. Too many to mention all of them. However a useful description of our ancestry begins with the time of Te Ao-matarahi. With him came the permanent occupation of the Tamatea people under the “heke” of Rakaihikuroa:

Rongokako

Tamatea

Kahungunu

Kahukuranui

Rakaihikuroa

Te Aomatarahi and Taraia came as the Warrior Chiefs of Rakaihikuroa Taraia’s descendants tended to remain in the Ahuriri-Heretaunga area, whilst Te Aomatarahi’s descendants occupied the coastal area.

However on his father’s side he was already connected to this district. His father was the famous Rakainui, and he in turn, was the grandson of Ueroa and Te We. Ueroa accompanied Kahukuranui in an earlier visit when the latter defeated the well known warrior Porangahau. Ueroa who was a grandson of Tahu of Turanga, married Te We, Porangahau’s daughter.

TAHU

Ira PORANGAHAU

Ueroa = Te We

Tahitotarere

Rakainui = Hinekahukura

Moengawahine TE AOMATARAHI

Ruaiti Rongomaipureora

Ngarengare Te Ikaraeroa

Tamatera TE ANGIANGI

Hinetemoa

TE WHATUIAPITI (of Pourerere

Parimahu

(of Central Hawke’s Bay Porangahau

Rotoatara Waipawa Poroporo)

Ruataniwha, Takapau,

Porangahau, Pukehou,

Kairakau)

Te Aomatarahi’s step-mother was Pouwharekura. She was of the Tamatea people and a descendant of Whaene. Te Aomatarahi married into his step-mother’s side by taking to wife two of Whaene’s grand-daughters, Houmearoa and Kuharoa, the sisters of Tutamure. Pouwharekura later become the last wife of Kahungunu.

TAMATEA

Whaene

Rongoiri

Ruariki

Pouwharekura

Te Aomatarahi was recently commemorated when the people of Takapau opened their new house Te Poho o Te Whatuiapiti at Rakautatahi. The Tekoteko of this beautiful wharetipuna is Te Aomatarahi and this bears witness to a continued veneration of him by his people. For the Takapau people he enters the district as a descendant of Tahu, whilst to seaward he is remembered as the descendant of Rongouera, better known as Porangahau.

TE ANGIANGI – TE WHATUIAPITI

Te Aomatarahi’s descendants begin the close connection with the people of Rangitane. His descendant Te Angiangi is particularly responsible for the gifts of land to Te Whatuiapiti and his related hapu. The famous food feasts led to the gift of the land and to further occupation and inter-marriage. The remaining hapu of the district reflect this era and their sub-tribal callings or karangatanga hapu are in reality both of Kahungunu and Rangitane, including Ngati Rangitotohu, Ngati Toroiwaho, Ngati Parakiore and Ngati Rangiwhakaera, Ngati Rangitekahutia.

Two of the kai-hau-kai (food feasts) which are part of the history of this district were Nga-tau-tukuroa and Te Uaua Tamariki. The feats were elaborate with related groups of hapu trying to outdo one another. The food was specially gathered and put into great piles carefully valued and named. The return feast had to return the same magnificence and if possible exceed it. When on these two occasions the return was thought to be less than the original gift of food, then the land was given over as compensation. It was by this means that the descendants of Te Whatuiapiti furthered their occupation. In particular the descendants of Te Rehunga and Manawakawa attained Otawhao and Whenuahou. Also the hapu of Te Rangiwawahia occupied from Porangahau down to Akitio.

Te Uaua Tamariki was a huge feast, with four whakatihi, or separate piles of food. The piles were prepared by their leaders and the hapu or subtribes.

1. Whakaararaumati: prepared by Hikarerepari Tamaiwaho and Toroiwaho.

Hikarerepari’s people – Ngai Tuwhirirau, Ngai Tangimoana.

Tamaiwaho’s people – Ngai Tahu.

Toroiwaho – Ngai Tunaiarangi.

Page 8

2. Toreopuanga – prepared by Huingaiwaho, Taurito and Kaitahi.

Their hapu were Ngati Hinepare, Ngai Tanehimoa, Ngai Tamatea and Ngati Hinetewai. Also Ngati Hoko, Ngati Mahu, Ngati Poporo and Ngati Kotore – these last four hapu proceeded on to the Wairarapa.

3. Rurupo – prepared by Hikataniwha and Manukirangaia. Their hapu was Te Aitanga a Tatai.

4. Rurea and Taiwha was prepared by Mutu and Kawewai and their hapu was also Te Aitanga a Tatai.

Hikataniwha, Manukirangaia, Mutu and Kawewai were all of the one family.

The circumstances leading up to this kaihaukai began when Te Whatuiapiti and Hikawera went to the Wairarapa together. Upon their return they, with Hikarerepari and Te Rangiwhakaewa, went to Turanga. They brought back with them the Ngai Tangimoana people who lived with Hikarerepari and Te Rangiwhakaewa. The feast Whareponga was prepared to which Te Angiangi came. He in return gave a feast. In return for Te Angiangi’s feast Te Whatuiapiti arranged Te Uaua Tamariki. The food was gathered from Raukawa, Ruahine, Rotoatara, Poukawa, Ruataniwha, Waipawa and Tikokino, within the boundaries of Taraia. Te Angiangi was unable to give a return feast that was to tally sufficient and the areas referred to above were duly occupied by the hapu of Te Whatuiapiti.

It was a descendant of Te Angiangi who met the first European known to Maori of these parts. The English explorer, Captain James Cook met the Chief Tuanui of Pourerere in the 18th Century. Tuanui’s descendants in this district, are the Tipene family of Porangahau, including the instigator of this exhibition, Rangitane Tipene, better known to his family and friends as Donald.

Te Angiangi

Te Ruahikihiki

Tipuaiwaho

Kihingaterangi

Te Rangitaurewa

Tuanui

Tamaiwhakahoroa

Hoani

Tipene

Taketake

Te Kakaho

Rangitane

NUKUTAURUA

This district was subject also to many raiding war parties. This brought about a high degree of shifting population, travelling and intermarriage.

The first taua was the northern “Amio-whenua”. Ngati Kahungunu, like many other tribes, felt the consequences of Ngapuhi access to European technology. Then Turoa of Whanganui led a taua which was also very well armed with muskets. Later, from Nukutaurua, Ngapuhi led a taua as part of a revenge expedition. A man called Toi, who like this tipuna Rakaihikuroa, wanted his son to be the “shining (and only) light in the sky” came to do away with local talent. The final taua known as Ngai Te Ihiihi led by the new invaders of Kapiti and Te Whanganui a Tara also brought a final episode of upset into the district. During much of this time the whole of Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa was left as an open battlefield and the people removed themselves to Nukutaurua on the Mahia Peninsula. Over a period of 15 years they fought battles and subsequently returned to evict the intending occupiers and to light their fires once again in the whole district.

HOKOWHITU

This exhibition Hokowhitu may also be seen in the light of the Te Maori exhibition. Te Maori was important for the role played by Maori people in exhibiting their cultural and artistic heritage, as artists, organisers and administrators and also as ceremonial experts and supporters. The mauri stone of Te Maori was brought to the Rongomaraeroa marae of Porangahau and was viewed by the people of this district. Tamatea Ariki Nui, centered its items on the theme of Te Maori for the 1984 Festival in Christchurch. Our tribal amorangi, Ti Te Tau Huata was responsible for the karakia which named the greenstone boulder, Te Maori and established it as the mauri for the exhibition.

The logo for Hokowhitu comes from the carving of the koruru on the original Te Poho Kahungunu meeting house of Ngati Kere. It was carved by Matenga Tukareaho of Ngati Rakaipaka, a signatory to the Treaty of Waitangi. In keeping with tikanga Maori there remains with this exhibition, as with all matters of importance, a turning to the past in order to focus the attention of both organiser and viewer. Appropriately the exhibition is intended as a memorial to Hokowhitu Ropiha, a person who worked tirelessly until his untimely death, to uplift his people, helping them to remain true to a priceless ancestral heritage of taonga Maori.

Te Whatuiapiti

Te Rangiwawahia

Kere

Te Ahurangi

Hineitaua

Whakamarino

Te Ropiha

Renata

Ieni

Hokowhitu

TAHA PAKEHA

We claim in this district the origin of the phrase “E tipu, e rea” from a waiata oriori of Te Wi of Ngai Tamatea. Apirana Ngata’s use of this phrase is extended by him to remind us also of our Pakeha heritage and its place in our lives. He places it firmly beside our Maori Heritage both together, and under the authority of God, as the means for our future development.

Page 9

From the time of Captain James Cook, and Sir Donald McLean a hundred years later, the descendants of Tamatea have lived together in peace and harmony with the first European settlers to these districts. They found a Maori population in full charge of their economic, social and cultural lives. Times have changed. Much has been lost. However a lot has been retained, and the Tamatea district of Central Hawke’s Bay enjoys a good measure of Maori-Pakeha co-operation and mutual respect.

Many of taonga of this exhibition have been retained by interested Pakeha people. Many were also gifted to settler families by Maori in return for services.

This exhibition takes place at a time of cultural renaissance for the Maori people of this district. This wider group now includes welcomed Maori from outside of Ngati Kahungunu as a whole, including Ngati Porou at Waipawa, Aotea and Tainui people in Waipukurau and indeed now, all tribal groups of Aotearoa. There are probably very few Maori if any who cannot tract a line of descent, or connection to Tamatea. The taonga of this exhibition therefore serve as a reminder to us of the early Maori settlers of this district, and also to the memory of those who gave their lives for the betterment of those who have come here to live.

Haere mai! Nau mai! Welcome! Come share in the history of our district. As we look at what remains of the expressions of our forebears let us be mindful also of the saying:

He toi whakairo, he mana tangata.

Where there is artistic excellence, there is human dignity.

Piri Sciascia

Wellington, 1990

Kiwi cloak presented by Rawinia to a Judge St. Hill.

Page 10

A VOYAGE ROUND THE WORLD

1773

October

Friday 22

In the morning we were to the south of Cape Kidnappers, and advanced to the Black Cape. After breakfast three canoes put off from this part of the shore, where some level land appeared at the foot of the mountains. They soon came on board as we were not very far from the land, and in one of them was a chief, who came on deck without hesitation. He was a tall middle-aged man, clothed in two new and elegant dresses, made of the New Zeeland flag or flax-plant. His hair was dressed in the highest fashion of the country, tied on the crown, oiled, and stuck with white feathers. In each ear he wore a piece of albatross-skin covered with its white down, and his face was punctured in spirals and curve lines. Mr Hodges drew his portrait, and a print of it is inserted in Captain Cook’s account of this voyage. His companions sold us some fish, while he was entertained in the cabin. The captain presented him with a piece of red baize, some garden-seeds, two young pigs of each sex, and likewise three pairs of fowls. Our young Borabora man, Mahine, who did not understand the language of the New Zeelanders at the first interview like Tupaya, hearing from us that these people were not possessed of coconuts and yams, produced some of these nuts and roots with a view to offer them to the chief; but upon our assuring him the climate was unfavourable to the growth of palm-trees, he only presented the yams, whilst we made an effort to convince the chief of the value of the presents which he had received, and that it was his interest to keep the hogs and fowls for breeding, and to plant the roots. He seemed to last to comprehend our meaning, and in return for such valuable presents, parted with his maheepeh or battle-axe, which was perfectly new, it’s head well carved, and ornamented with red parrot’s feathers and white dog’s hair. After a short stay he returned on deck, where Captain Cook presented him with several large nails. He received those with so much eagerness that he seemed to value them above any other present; and having observed that the captain took them out of one of the holes in the capstan, where his clerk had put them, he turned the capstan all round, and examined every hole to see if there were not some more concealed. This circumstance plainly shows how much the value of iron tools is advanced in the estimations of the New Zeelanders since the Endeavour’s voyage, when they would hardly receive them in many places. Before their departure they gave us a heeva or warlike dance, which consisted of stamping with the feet, brandishing short clubs, spears, making frightful contorsions of the face, lolling out the tongue, and bellowing wildly, but in tune with each motion. From their manner of treating the fowls which we had given the [them], we had no great reason to expect success in our plan of stocking this country with domestic animals, and we much feared whether the birds would reach the shore alive. We comforted ourselves however, with the thoughts of having at least attempted what we could not hope to see accomplished.

The wind, which had shifted during our interview with these savages, blew right off shore, and was very unfavourable. It encreased towards evening into a hard gale, during which we hauled our wind, and stood on different tack for fear of being blown too far from the coas.t heavy rains attended this gale, and penetrated every cabin in the ship. Squalls were likewise frequent, and split some old sails, which were not fit to resist the violence of the tempest. We had not expected such a rough reception in the latitude of 40o south, and felt the air from the bleak mountains of New Zeeland very cold and uncomfortable, the thermometer being at 50 degrees in the morning.

Ref. A Voyage Around The World. Vol. 1, Forster, George F.R.S. London 1777

Photo caption – An engraving from the original sketch of Tuanui.

Page 11

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CENTRAL HAWKE’S BAY

Nigel Prickett

Archaeologist, Auckland Museum

The first people to live in the region now known as Hawke’s Bay were Polynesian ancestors of the Maori people. They arrived here on the generally exposed and often windswept coast as much as a thousand years ago and for most of our region’s human history they were the sole human inhabitants. Only a century and a half ago did another people arrive to transform the landscape and change forever the ancient way of life of the first settlers.

Archaeologist in New Zealand have for many years been interested in the Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa coasts between Cape Kidnappers and Palliser Bay. As early as 1947 the late Dr H.D. Skinner of Otago Museum visited southern Hawke’s Bay and saw amongst other things a necklace of imitation whale-teeth made of shaped whale ivory, then in the possession of Mr Percy Hunter of Porangahau (1). This important find, now in the National Museum, Wellington, has been returned to Hawke’s Bay for the ‘Nga Taonga O Tamatea’ exhibition.

Another important find, from Pakuku near Akitio, is an unusually massive so-called ‘reel’ pendant, or necklace unit, in the Simcox Collection, Hawke’s Bay Museum, Napier. These two items along with many others date from the early period of Polynesian settlement in New Zealand when Maori ancestor still closely followed the older central Pacific models in their ornament and tool styles. Stone adzes, fish-hooks, ‘minnow’ lure shanks and other items found along the coast south of Cape Kidnappers over many years relate to earlier East Polynesian forms. Together they show that this part of Aotearoa was settled early by Maori ancestors, perhaps as much as a thousand years ago.

A second matter of interest to archaeologists in the possibility that the earliest settlers here hunted and ate the moa. In sand dunes from Ocean Beach south are found the bones, egg shell and polished crop stones of the extinct giant flightless bird. An early report (2) concluded that moa remains pre-dated evidence of human living sites in the dunes. Where they were apparently associated this was the result of wind erosion blowing away the sand and mixing the moa bones with deposits resulting from later human occupation. A brief archaeological survey last summer (1989-1990) confirmed this at Ocean Beach, and at Porangahau where the remains of a Dinornis, the largest of 11 species of moa, were found. Nonetheless, one day an old living site may be found with evidence that people in our district did once hunt and eat the giant bird.

A third area of interest is the presumed importance of kumara agriculture. Along parts of the Wairarapa coast to the south are extensive areas of stone-walled garden plots. In the 1970s these were subject to a detailed archaeological study by Hele Leach (3) who showed that Palliser Bay examples date from as early as the 12th century A.D. There can be little doubt that kumara was also grown on the frost-free coastal platform of Central Hawke’s Bay at this early date, but here we do not have the evidence of stone walls and mounds. What is more, in large areas, for example at Porangahau, wind erosion of the sand flats in recent decades has destroyed almost all the early archaeological landscape.

Human settlement of the Hawke’s Bay region had a devastating effect on the natural world. A study of microscopic pollen plant remains at Lake Poukawa (4) shows that as much as a thousand years ago bracken and scrub was increasing at the expense of podocarp forest. Fragments of charcoal suggest that this was as a result of the gradual burning of original forest in an area vulnerable because of low rainfall. Forest birds, many of them to become extinct or locally extinct, suffered from hunting pressure as well as from destruction of habitat.

A picture can be built up on the earliest human settlement in our region. On the coast, sea and shore gave food familiar and important to Polynesians everywhere. The narrow

Photo captions –

Fig. 1: Hunter necklace.

Fig 2: Pakuku reel.

Page 12

coastal shelf provided river-mouth village sites and extensive areas of light warm soils for tropical food plants, most importantly kumara. Behind the coastal platform forest ranges and river valleys provided great timber trees for buildings and canoes, birds for food, and plant products for food as well as for a wide range of practical needs including medicines, fibres, dyes and wooden implements.

In the ‘Nga Taonga O Tamatea’ exhibition are many items which, from their style and sometimes also from the location of their discovery where it is known, may be included among the artefacts of the first settlers of the Hawke’s Bay coast. Already mentioned are the Hunter necklace (Fig. 1) and Pakuku ‘reel’ ornament (Fig. 2). Other illustrated items are the one-piece bait hooks in bone or ivory (Fig. 3), a harpoon point from Blackhead (Fig. 4), and two important adzes (Fig. 5 and 6).

Except for the necklace and the extraordinary Mangakuri adze all these items belong in the Simcox Collection, put together over many decades by Dr John Simcox of Weber. His unparalleled collection of Maori artefacts from the Hawke’s Bay coast is now in the museum at Napier. It was obtained mostly from the area between Blackhead and Akitio where Simcox regularly visited windblown sites known to him. The majority – perhaps all – of these sites were ‘archaic’, that is, they date from the first period of human occupation of Aotearoa, until about the 15th or 16th centuries.

Notable in the Simcox Collection, and indeed in other local collections, is a group of adzes made of local Owahanga silicified limestone. The latter is of hard workable quality when fresh but quickly weathers to a softness quite useless in the fools which were being made. Nonetheless it was

Fig. 3: One piece bait hooks in bone or ivory.

Fig. 4: Bone harpoon points date from the early centuries of Polynesian settlement in New Zealand. This example found near Blackhead is an important item in the Simcox Collection, Hawke’s Bay Museum.

Page 13

extensively used in the early period as the basis of an important local stone industry. There are both finished and uncompleted (‘rough-out’) adzes on show in the exhibition.

More important as an early adze making stone is metasomatized argillite from the Nelson region. In her 1982 summary of Hawke’s Bay archaeology Aileen Fox remarked that fully half of all adzes in the Hawke’s Bay Museum were made of Nelson argillite (5). Most of these are made to early forms. Among the largest of argillite adzes found anywhere in New Zealand is one from Mangakuri, near Pourerere, now held in the Canterbury Museum (Fig. 5). It is made of black stone from the Mt Ears quarries on D’Urville Island, and is fashioned to the familiar rectangular cross-sectioned form by flaking, with some hammer-dressing in places. For some reason it has not been polished which would normally be the final stage of manufacture. Adzes like this were used for cutting or shaping large timbers. One of this size must surely have had an important, possibly ceremonial role.

Less common are early adzes made of basalt from the Tahanga quarry, Coromandel Peninsula. In the Simcox Collection is an outstanding triangular cross-sectioned adze probably of Tahanga basalt (Fig. 6).

Another important stone material in use early in the Polynesian settlement of New Zealand was serpentine. Like argillite it comes from the Nelson district. It is a soft black of green rock mineralogically related to pounamu (jade).

From serpentine was crafted a range of early personal ornaments including breast plates, imitation whale tooth pendants, and ‘reel’ necklace units such as that from Pakuku (Fig. 2). The Pakuku reel is unusual in its large size and in the many little holes drilled into both ends. At some stage a start was made towards reducing it in size by about one-third.

Fig. 5: From Mangakuri near Pourerere comes one of the largest of all Maori stone adzes. Made of argillite from D’Urville Island near Nelson, the unpolished adze measures 566mm in length, 132mm maximum width and a greatest depth of 6 mm. it weighs 6.65kg. the shape dates it to early in the Maori history of Hawke’s Bay.

Canterbury Museum E165.287

Fig. 6: The regular cross-section of this finely finished adze suggests an early date, probably prior to the 15th or 16th century. The raw material is basalt, almost certainly from the Tahanga quarry, Coromandel Peninsula.

Page 14

The ‘Nga Taonga O Tamatea’ exhibition also includes two smaller serpentine reel units from the Hunter collection, Porangahau. One is a highly polished example with three ridges while the second is more unusual with two broad ridges. The Hunter necklace also includes two ivory reels (Fig. 1). All this material was found on the Porangahau sand flats which was clearly an important focus of early settlement.

Another important find from the north end of the sand flats, near Blackhead, is the harpoon point shown in (Fig. 4). Again, this artefact is strong evidence of early occupation. Other harpoon points from the Hawke’s Bay coast include a small but beautifully finished example in ivory from near Cape Turnagain and a fragment from Burnview, both of these also in the Simcox Collection.

Between the earliest settlement of Aotearoa and the arrival of Europeans many hundreds of years later there was a gradual change in many aspects of the Maori way of life. Indeed, the first settlers did not arrive as ‘Maori’ at all but as ‘Polynesians’ from the tiny tropical islands of the central Pacific. It was only in the isolation of the new and very different New Zealand environment that a way of life evolved which was uniquely Maori while owing much to Polynesian origins.

In Hawke’s Bay there has been little archaeology carried out to throw light on change and growth in the 800-1000 years of pre-European settlement. From knowledge of other regions in New Zealand it may be suggested that here too the 15th and 16th centuries mark a high-water mark of change in population, economy, technology and settlement pattern. Before this a small population whose settlements lay largely on the coast was able to exploit an environment previously untouched by man, or indeed by any other mammalian predator. As we have seen the tools and ornaments these people made owed much to old Polynesian forms.

Gradually, however, the population grew, artefact forms changed, the pattern of settlement developed to meet near needs and the environment was greatly altered to man’s purpose.

Regarding those artefacts which have come down to us – mostly of stone and bone, fibre and wood generally have not survived – the Hawke’s Bay region shares with the other parts of New Zealand the increasing importance of pounamu (jade) for ornaments, adzes and chisels, and the development of an adze industry based on local raw material. For the latter the rock used was greywacke obtained from the eastern ranges or, more likely, from the boulder-strewn riverbeds which originate there. The character of the rock demanded different techniques of adze manufacture from those employed with argillite, basalt and Owahanga limestone in the earlier period. From greywacke were crafted highly characteristic Hawke’s Bay adzes – large, almost square in cross-section, with a steeply bevelled on blade and sometimes bearing a simple spiral design pecked in the butt. There are several such adzes in the ‘Nga Taonga O Tamatea’ exhibition, including an enormous example from Hatuma is green greywacke which is held locally.

Pounamu hei tiki are perhaps the best known of all Maori ornaments. The use of this tough intractable stone required special skills and techniques; its presence in archaeological sites, commonly as adzes or chisels, generally indicates a late date. By the 19th century the hei tiki was the most highly prized of all Maori ornaments, a popularity it has held to this day.

On the hill-tops and ridges of much of Central Hawke’s Bay are the earthwork remains of Maori fortifications or pa. most of these historically important and evocative landscape features probably date from the 17th century and later. Little excavation has been carried out however, and a great deal of work is needed to thoroughly test such generalisations. Nor is archaeology the only way to the history of these places as traditional accounts are increasingly useful regarding the later Maori centuries in Hawke’s Bay. One pa that has been excavated is Tiromoana, near Te Awanga,

Photo captions –

Fig. 7: Serpentine reels.

Fig. 8: Ngarongo.

Page 15

where Aileen Fox has dated initial fortification of the ridge end to the late 15th century (6).

The little that can be surmised of the history of artefacts on show in the ‘Nga Taonga O Tamatea’ exhibition and of the settlement sites of coastal and inland Hawke’s Bay, from which they have been recovered depends very largely on archaeological work done elsewhere in New Zealand. Almost nothing is known of the particular history of the first settlers of our region for the first several hundred years of their living here. Very little archaeology has been done, and the great majority of early sites are already destroyed by natural or human agencies. The conservation of remaining historic sites is a community responsibility of the utmost importance. There is a remarkable story waiting to be told of the arrival of the first people to live in our region and of the life they made for themselves in the new land. It is a history which will rely largely upon archaeology.

NOTES:

1. See Roger Duff, “The Moa-hunter Period of Maori Culture”, Government Printer, Wellington, 1956, page 117.

2. H. Hill, “The Moa – Legendary, historical and geological”. Pages 330-351 in Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute, Vol.46, 1914, page 343.

3. Helen Leach, “Evidence of Prehistoric Gardens in Eastern Palliser Bay”. Pages 137-161 in “Prehistorical Man in Palliser Bay” (National Museum of New Zealand Bulletin, No 21), 1979.

4. M.S. McGlone, “Forest destruction by early Polynesians, Lake Poukawa, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand”. Pages 275-281 in Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, Vol. 8, 1978.

5. Aileen Fox, “Hawke’s Bay”. Pages 62-82 in The First Thousand Years (ed. N. Prickett), Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1982, page 65.

6. Aileen Fox, “Tiromoana Pa, Te Awanga, Hawke’s Bay, Excavations 1974-5”. New Zealand Archaeological Association Monograph, No. 8, 1978, pages 28-29.

Page 16

Carvings from the former meeting house at Porangahau called “Te Poho O Kahungunu” completed in February 1875. The house was carved in northern Ngati Kahungunu style by Matenga Tukareaho and his son Hami Te Hau of Nuhaka.

As a young man, Matenga (Marsden) Tukareaho was instrumental in introducing the gospel to northern Hawke’s Bay, after returning from a visit to the missionaries at the Bay of Islands in 1834. Matenga was also a signatory to the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

In 1910, a new Poho-O-Kahungunu house carved by Hokowhitu McGregor of Nati Raukawa replaced this first house.

The carvings referred to are the pare, the waewae, the poutokomanawa and koruru.

Page 17

The lower ends of five meeting house rafters and four poupou in Arawa style. They are almost identical with rafters in the house “Kahuranaki” at Te Hauke, carved in 1912 by Neke Kapua, Te Ngaru Ranapia and others, all of Te Arawa. These rafters were probably carved at that time, perhaps for another house in the district.

Page 21

TAONGA

The respect, mana and aroha for Taonga exists today. The techniques are slightly different, modern technology has provided a wider and more practical range of tools, but the methods are the same.

Nature still provides the source of materials while new talents fashion the art forms. Fortunately, throughout the Tamatea region, there is an abundance of artists and crafts people. Positively, there is an assurance that the value and appreciation of our unique works of art, our Taonga, lives on.

The following pages show a selection of contemporary works included in the exhibition by Alan Wakefield (carver bone and wood), Maureen Wakefield (weaver), and Jack Tipene (carver, wood).

Hei matau, Alan Wakefield.

A combination of 3 different materials whalebone (point), wood (shank), muka, flax fibre (cord). A modern work of art based on traditional patterns.

NGA TAONGA O TAMATEA TRUST ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

TE RUNANGANUI O NGATI HAKUNGUNU

CENTRAL REGIONAL ARTS COUNCIL

MASPAC

TAMATEA TAIWHENUA

CENTRAL & SOUTHERN HAWKE’S BAY ARTS COUNCIL

N.Z. 1990 COMMISSION

C.O.G.S.

HAWKE’S BAY CULTURAL TRUST

A.N.Z.

D.E.C.S

TURNBULL LIBRARY

NATIONAL ART GALLERY AUCKLAND

NATIONAL ART GALLERY, AUSTRALIA

NAPIER MUSEUM

MANAWATU MUSEUM

NATIONAL MUSEUM, WELLINGTON

CANTERBURY MUSEUM

OTAGO MUSEUM

N.Z. FILM ARCHIVES

CENTRAL HAWKE’S BAY DISTRICT COUNCIL

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Description

[List of names in this title still to be added – HBKB]

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.