- Home

- Collections

- SANKO PJ

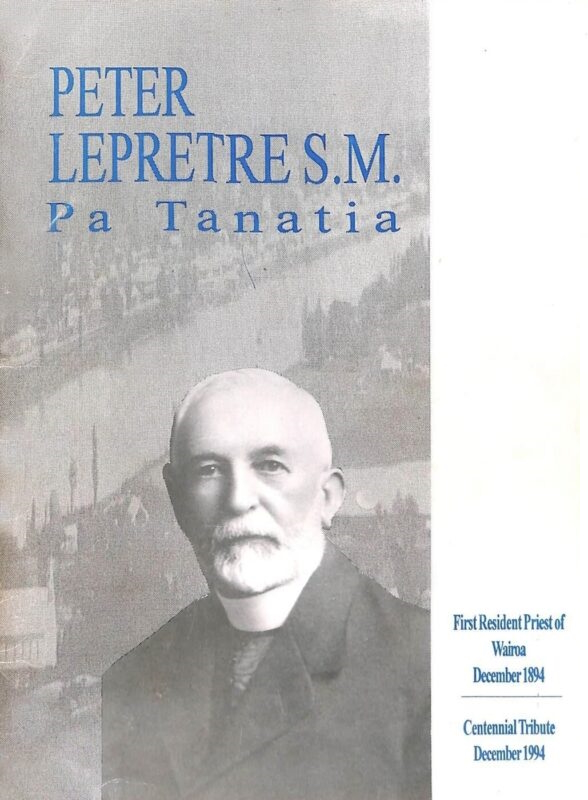

- Peter Lepretre SM

Peter Lepretre SM

FOREWORD

One hundred years ago, on 2 December, Peter Lepretre arrived in Wairoa to make his residence there. He could not have known that Wairoa would be home to him for the rest of his life. Once todays Catholic community had decided to honour this centenary, a commemorative booklet was proposed as a significant part of the celebrations. This was agreed on and a small group was asked to produce a booklet. What has resulted is not, perhaps, as stylish a production as might have been wished. Fr Lepretre is certainly deserving of the best but we had to be realistic about the resources available. We wanted a resonable priced booklet that would reach a wide number of families.

It is appropriate to acknowledge help received. Wellington Diocesan Archives and Marist Archives have willingly made there [their] resources available. Br Gerard Hogg has delved in the latter with great tenacity. John and Margaret Swan have helped greatly with photos and facts of Wairoa. The locals here and everywhere have dipped into there memories and albums to see what treasures were there. In general, wherever help was sought, there was always a willing response. Gisborne Photo News have produced the booklet. They were able to see at the outset that it was possible to marry our high hopes with our low budget. This gave us the confidence to press on. We leave our readers to appreciate the high quality of the finished product.

The committee has enjoyed the task given it. To save future researchers unnecessary sleuthing, section 3 was written by Max Crarer. Fr. Noel is answerable for the remaining sections. Our goal was not of course to write the definitive life of Peter Lepretre. We have tried to pay him a sincere tribute of thanks. Ko tenei he tohu aroha mo Pa Tanatia

Biddy Bretherton

Max Crarer

Noel Delaney S.M.

Molly Thompson R.S.J.

Page 1

THE EARLY YEARS 1

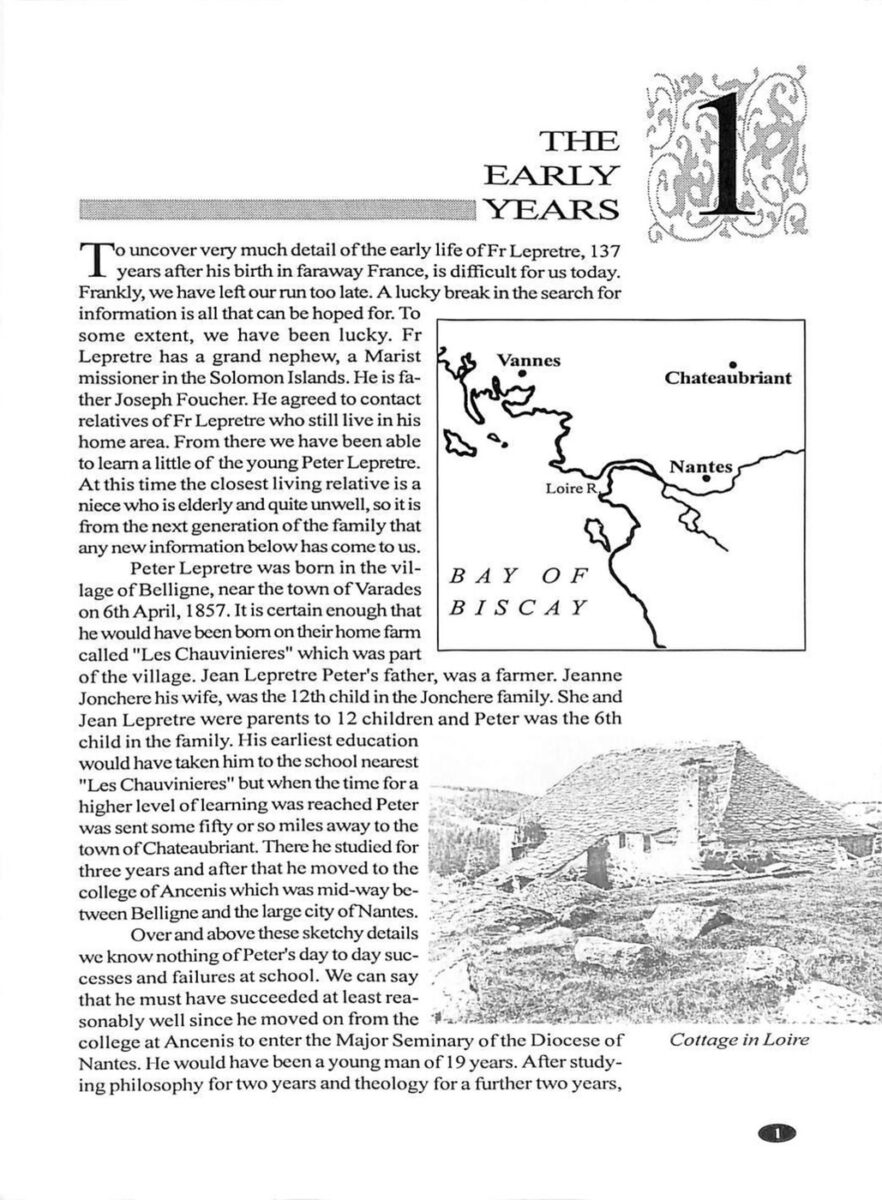

To uncover very much detail of the early life of Fr Lepretre, 137 years after his birth in faraway France, is difficult for us today. Frankly, we have left our run too late. A lucky break in the search for information is all that can be hoped for. To some extent, we have been lucky. Fr Lepretre has a grand nephew, a Marist missioner in the Solomon Islands. He is father Joseph Foucher. He agreed to contact relatives of Fr Lepretre who still live in his home area. From there we have been able to learn a little of the young Peter Lepretre. At this time the closest living relative is a niece who is elderly and quite unwell, so it is from the next generation of the family that any new information below has come to us.

Peter Lepretre was born in the village of Belligne, near the town of Varades on 6th April, 1857. It is certain enough that he would have been born on their home farm called “Les Chauvinieres” which was part of the village. Jean Lepretre Peter’s father, was a farmer. Jeanne Jonchere his wife, was the 12th child in the Jonchere family. She and Jean Lepretre were parents to 12 children and Peter was the 6th child in the family. His earliest education would have taken him to the school nearest “Les Chauvinieres” but when the time for a higher level of learning was reached Peter was sent some fifty or so miles away to the town of Chateaubriant [Chateaubriand]. There he studied for three years and after that he moved to the college of Ancenis which was mid-way between Belligne and the large city of Nantes.

Over and above these sketchy details we know nothing of Peter’s day to day successes and failures at school. We can say that he must have succeeded at least reasonably well since he moved on from the college at Ancenis to enter the Major Seminary of the Diocese of Nantes. He would have been a young man of 19 years. After studying philosophy for two years and theology for a further two years,

Photo caption – Cottage in Loire

Page 2

Peter was judged ready to receive minor orders and did so. We can only speculate now about the background to his Marist vocation. How he came to know about the Society of Mary and what led to his interest in becoming a Marist have not been recorded for us. The city of Nantes is on the Atlantic seaboard of France, west and a little south of Paris. It was not part of France where the Society had been invited to begin any of its apostolic works in the time that Peter was growing up.

It is interesting to note however, the number of young men who joined the Society of Mary around this time from the diocese of Nantes. The earliest religious profession in the Society of Mary of a man from Nantes diocese, was 1841 and this was a man never to be forgotten in Wairoa, Euloge Reignier. There were thirty young men professed as Marists from that year until the end of the century. New Zealand did well from this diocese, especially in men who gave sterling service ministering to the needs of the Maori people. Euloge Reignier, Christopher Soulas, Cyprian Huchet, Peter Lepretre, Francis Melu, Peter Broussard, Julien Maillard and Jean-Marie Vibaud were all vocations from the diocese of Nantes.

Apart from personal contact with Marist Religious in France there were other ways that missionary vocations as such, and Marist vocations in particular, were fostered. From the city of Lyons a publication called the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith was widely disemminated [disseminated] in France. Letters from missionaries in the field, and accounts of emerging Christian communities in faraway countries, inspired many young French men and women to follow a call to life as missionaries. There were times too when Bishops from emerging dioceses went on preaching tours in cathedral churches of France in the interests of their “foreign missions”. It was this kind of occasion for example, in the cathedral of Rheims, that moved a soldier of the French army Maurice Boch, to hand over his rifle and become a Marist missionary in the early 1900’s in Bougainville. There is a sequel to the Boch story that is worth telling. When news came to him that in the 1914-18 war the Germans had bombed the cathedral of Rheims where he had been ordained, Boch took temporary leave of his mission to rejoin the French Army. Vengeance for the desecration of Rheims had to be exacted. But by the time he reached France the war was over. C’est la vie. Of Peter Lepretre we do not have this kind of background information. That the seeds of a Marist vocation had been sown in his heart became clear when he was invited in 1880 to go to Dundalk, Ireland, to make his novitiate

It was in 1861 that the Society of Mary opened a school in

Photo caption – Euloge Reignier SM

Page 3

Dundalk, a town of 11,000 people on the east coast of Ireland and on the border of the Six Counties of the North. It was called St. Mary’s Collegiate school. The first rector was a French Marist, John Leterrier. He was later to become the first Marist Provincial in New Zealand from 1889-1894. The prospectus for the opening of St. Mary’s school appeared in the “Dundalk Democrat” in August 1861. It gave a fulsome account of the excellent education parents and students could hope for at St. Mary’s. A final paragraph raises another matter:

“As the fathers of the Society of Mary devote themselves to the home and foreign missions, they will also admit and board in their house a limited number of novices who will receive instruction in philosophy and theology”

Part of the reason for Marists to accept this teaching apostolate in Dundalk was the opportunity for some French Marists to become proficient in spoken English. This would serve them well in Australasia and other English speaking mission countries. In Peter Lepretre’s case however, there was further reason. In 1880 the French Government set about to implement new anti-Religious laws. Religious were expelled from teaching in schools, houses of formation for Religious were closed and many Religious were compelled to leave their homeland. Dundalk then became the logical place for Peter to fulfil his canonical novitiate. So he spent one year on Irish soil. It is interesting to note that James Hickson, later to be Parish Priest of Wairoa, entered Dundalk two years earlier in 1878.

As a newly-professed Marist, Peter was posted to St. Joseph’s College Montlucon. This was a town a hundred kilometres or so west of the city of Lyons. The Society of Mary opened this college as early as 1853. For the next two years he was Vice-Principal of the school. On the 7th February, 1882, he made his perpetual profession as a Marist and went then to Barcelona in Spain to complete his theology studies with other Marists there. On 24th August, 1884, he was ordained to priesthood in Lyons by Bishop Dubuy [Dubois?] whose diocese was in Galverston, Louisiana [Galveston Texas?], USA. Soon after ordination, he would have returned to the home farm of “Les Chauvinieres” to rejoice with his family and would surely have visited the Major Seminary of Nantes and other places which had helped him along the way to becoming a priest of the Society of Mary.

Brothers or priests of the Society of Mary who wished to be part of the missions of Oceania had to make an approach to the Superior General. We do not know the story of Peter Lepretre’s missionary vocation – what inspired him to make the choice to leave family and fatherland for the faraway regions of Oceania. What we do know is that his parents were very unhappy about his impending

Photo caption – Chapel Novitiate

Page 4

departure. For him also, leaving home would have been a human wrench despite the Christian commitment that inspired it.

On 17th December, 1884, just four months after ordination, Peter left Marseilles aboard the “Caledonien” a French Steam Ship. With him were three Marist companions. By way of Suez, Aden, Mauritius, Adelaide and Melbourne they arrived at Sydney on 31st January, 1885. By and large wind and weather proved favourable throughout the long journey. In Melbourne the “Advocate” gave details of cargo and passengers and noted: “The steamer is in her usual yacht-like order”. After a little time with the Marists in Sydney, Lepretre and one companion of the journey Francis Huault, took ship for Wellington where they arrived on 16th February. Peter was 28 years of age.

WAIROA LIFE: EARLY DAYS

1841: Fr Claude Baty visits Wairoa.

1844: Rev J. Hamlin plants first blackberry.

1851: Fr Baty dies in New Caledonia.

1853: Settlers establish own local government.

1857: Peter Lepretre born. James Carroll born.

1865: Government buys 4,750 acres for town of Clyde.

1869: Mohaka affray with loss of life.

1877: Local Government authorised: Town population 100 settlers.

1879: Sister Mary Joseph Aubert makes a perilous journey to Wairoa to tend Fr Reignier “At the Gates of Death”.

Page 5

MISSION WORK 1885-1894 2

Within three weeks of embarking at Wellington in December 1885, Peter arrived at his first permanent residence in New Zealand. On March 4th he reached Hiruharama (Jerusalem) on the Wanganui River. The main reason for this appointment was to enable him to learn the Maori language. Apart from the help the Maori people would be able to give him, there were Fr Soulas and Sister Mary Joseph Aubert to guide him. From the desolation following the 1864 battle of Moutoa near Hiruharama, Catholic life began to revive there when Christopher Soulas and Sister Mary Joseph came from Pakipaki in 1883 to take up residence. This village was a good environment for the new recruit to be schooled for the apostolate to the Maori people. This is not to underestimate the extent of culture shock that the young man fresh from France would have to contend with. At the end of 1885, we get a valuable insight into Jerusalem from a letter written by Archbishop Redwood to the Marist Generalate in Lyons.

“I have just spent Christmas day at Hiruharama,” he begins. “I abandoned my cathedral and went to spend Christmas among my happy Maori people. There were 50 confirmations, 500 people gathered to celebrate Christmas, beautiful singing in Latin and Maori and after the principal Mass we had a superb banquet. The Maori people did it all themselves without help from the Sisters or other Europeans and there were dishes a la Maori, a la French and a la English catering for all tastes”

So Peter’s first Christmas in New Zealand must have been memorable enough. In his letter the Archbishop spoke of a new enthusiasm in the mission that was very consoling. “Fr Melu already speaks Maori well and Fr. Lepretre is pitching in bravely and is promising to speak Maori one day with the purest accent. When we are able to, we dream of setting up other centres of missionary activity.”

The good Archbishop was full of optimism.

Photo cations –

The young Peter Lepretre

Jerusalem 1886

Page 6

In fact, the dream became reality very quickly. Fr Melu was posted to Otaki where he accomplished prodigious deeds. On 28th March 1886, Fr Lepretre moved to Pakipaki where he occupied the mission house built in 1880 by Fr Soulas and vacated by him in favour of Hiruharama three years later. It is interesting to reflect now on the assignment this young missionary priest was given. He was 29 years of age, he had been ordained for less than two years and he had had one year of preparation at Hiruharama for this new posting. In that year there were only four baptisms recorded as celebrated by him and the entries in his handwriting show a tentative approach in recording Maori names. Reflecting on his Pakipaki assignment many years later, Fr. Lepretre stated “I came to Pakipaki in 1886. As I said, I was in charge of all the East Coast from Gisborne to Wellington. There was a good number of Maori in Hawkes Bay. Fr Delach arrived in 1890 (actually 1891 Ed.) and came to Pakipaki with me”. So for the first four years, Gisborne to Wellington was his sole charge. The Marist mission at Meeanee 20 miles away was well established of course, but by now Fr Reignier was an invalid and Fr Yardin, who came to support the old man, had no experience in the apostolate to Maori people. The extent of territory covered by the young Lepretre, as we see it in part in his register of baptisms, is hard to believe. On 4th March 1886, Lepretre had arrived at Pakipaki. Soulas’s little church had lost all its paint and was “quite naked.” By May he can report to Soulas that he has been to Napier and other parts of Hawkes Bay and has spoken to Father Reignier. His first visit to Wairoa was late in August and his first baptism was an infant Tihemi Rui at Kihitu. Among others baptised on this visit were William and George Maurel (sic). He visited Mahia at this time and reported on his return to Pakipaki that most of the Mahia Maori were Mormon.

By mid 1887 he is ready to venture south. At Te Oreore near Masterton he finds a large group of Catholics, with others interested and asking for baptism, but he is going to spend time instructing them in the faith. On 13th September he writes to Soulas from Masterton in reflective mood. Hawkes Bay is proving difficult because the Maori are so spread out. Moreover, the “melange” of Maori and Pakeha works to the disadvantage of the former. Hopes were high for Wairoa. “Last time I was there a number came to Mass. The only thing is, they say, it happens too infrequently and they are often neglected.” Te Oreore seemed promising and the people were talking about building a church. The church of the Sacred Heart was indeed built and opened by Archbishop Redwood in March 1890. Today it is

Photo captions –

Pakipaki Mission

St. Stephen’s Te Oreore

Page 7

still in a very tidy condition. There were baptisms also at Hauharetu near Upper Hutt. When it was time to return home he writes “I went back to H.B. along the sea coast, Castlepoint, Matakaikona, Akitio, Wainui, Porangahau, Wanstead and Waipukurau, saying Mass and baptizing etc. as I went along.” His hope was to visit southern parts of his mission every five weeks.

After three years of this solo missionary work, Peter is writing to M.l’abbe Colas, a priest of the city of Nantes.

“My silence is not the result of forgetfulness, and you must excuse a missionary whose district extends 140 leagues (420 miles) in length and 40 leagues (120 miles) in width. I am always on the tramp from village to village, always sorry that I am not able to be everywhere at once. During my visit to a village, morning prayer is said in common during Holy Mass. In the evening the bell calls my flock for catechism and night prayer. A meal follows. Then we all meet in the main house of the village for rosary, a chat and a sing-song. The main portion of the day-time is spent on visits, personal interviews and instructions. In spite of the vexations, humiliations, disappointments and great sufferings which are the daily bread of a missionary, I assure you we are not without many consolations. I do love my missionary life, and it would cause me much pain were I to be parted from these dear Maori people whom I have instructed and baptised.”

By early 1891 Fr Francis Delach was posted to Pakipaki as an assistant missionary. He had arrived from France on New Years day, a man nine years younger than Peter Lepretre. It was as well that he arrived when he did. An absence of Lepretre’e[s] name in the baptismal register along with an entry in an 1891 “Wairoa Advocate” give us important information. Lepretre’s health was causing concern. Our trusty “Wairoa Advocate” reports:

“We are glad to hear from Sydney that the health of Fr Lepretre is rapidly improving. The expectoration of blood from which we regret to say the Rev. Father was suffering, has now almost ceased and he is gaining in weight daily This will be good news to the numerous friends of the Rev. Father in New Zealand who will, we are sure, join with us in the fervent hope that he may soon be sufficiently restored to resume his missionary labors among the Maoris.”

It seems that he was on sick leave from March 1891 to May 1892. Most of 1891 was spent in Sydney. By late January 1892 he had returned to New Zealand “much improved.” He is baptizing again by 26th May. So the work based at Pakipaki goes on. There were busy years in 1892 and 1893, with frequent visits to Wairoa. There were several baptisms at Ruakituri. To the two men resident at Pakipaki it must have seemed as though settled days had come at last. Within three years however, Pakipaki was abandoned for a second

Page 8

time. In 1893 Delach went to Otaki. Lepretre moved out in August 1894 and in November was officially named resident priest in Wairoa. The unpredictable circumstances that made these changes necessary were given in 1926 in a letter he wrote to a young Kiwi Marist, Augustine Venning:

“The reason Pakipaki was left for Otaki in 1893 and then for Wairoa was this. The Maoris had a big meeting (te Kotahitanga) at Waipatu near Hastings. All the Maoris were at it. An old woman and her not too honest daughter were at home. Mr G.P. Donnelly and his groom drove to Pakipaki, a lawyer Mr Lewis from Havelock North came, they went to the old lady’s house near the church, the lawyer came to me for a pen and ink The old lady forced by her daughter sold all the land from Pakipaki to the road to Maraekakaho, (having been in H.B. you must know the place). The Maoris hearing this had a big tangi, petitioned the government for the sale to be repealed, but nothing could be done. The Maoris went about 7 or 8 miles from Pakipaki, so we were told also to leave Pakipaki. I went to Wairoa after Fr Kerrigan’s death on August 6th 1894. For a long time I came twice a month to Pakipaki for about 10 years and then the priests of Otaki took charge of it until about four years ago.”

This section of Lepretre’s letter to Venning would be interesting to research further, but that would be outside the scope of this booklet. Some background however, can be given. We do know that the Kotahitanga (The Maori Unity Party) did meet at Waipatu from May to June 1892. Key figures named do have established places in Hawkes Bay history. G.P. Donnelly, who married the high-ranking Airini Karauria, certainly came to own land in the Pakipaki area. The church and mission house at Pakipaki were certainly built on a land block known as Kakiraawa. It was a block of 3,043 acres set up by the Crown in 1866. There were eight names in the title grant, one only of whom is a woman. Another is Urupene Puhara, of whom more will be said elsewhere. It is significant to note that the alienation of the Heretaunga lands in the last century – forced or contrived as researchers are beginning to reveal – seem to have directly influenced Lepretre’s and Delach’s lives. The “melange” of European and Maori in Hawkes Bay which Lepretre has referred to as working to the disadvantage of the latter seems, in this case, to have worked to his disadvantage.

WAIROA LIFE: 1880’s

1880: St Paul’s Vestry proves a fire alarm bell

1881: Owners of gorse hedges to be warned of spreading the weed

1882: St Peter’s Church built

1885: Fr Yardin goes to Meeanee

1886: Five live rabbits sighted in Mr Poyzer’s garden

1888: First Wairoa Bridge opened. Tolls charged Children going to Church free

1888: Fr Lepretre sings the Requiem Mass for Fr Reignier’s funeral.

Page 9

THE WAIROA OF 1894 3

What did our first resident priest find when he took up his appointment in Wairoa? As anything I write will only be gleaned fron [from] newspapers or documents of that era, it would seem more fitting to commence with a description of Wairoa written by Francis Yardin, who visited the Wairoa-Waikaremoana area, in the company of Fr Lepretre and a Mr Malony, in the early 1890s. This was just a part of a very extensive walking tour the trio made at this time. Fr Yardin (1824-1904) was originally stationed in Lyons where he spent many years as Procurator for the Marist Missions of Oceania. His role was to supply from France many of the religious and material needs of Marists all over the Pacific. He came to New Zealand in 1875. His last posting was to Meeanee, Hawkes Bay, in 1885, where he died eight years later. I quote his words:

“Wairoa is a small town of 400-500 inhabitants, situated on the right bank of the river of this name, some two miles from its mouth, and 42 miles from Napier. Not yet thirty years ago it was called Clyde, but the inhabitants renounced this official name to give it that of their beautiful river, and their choice was made law. The embankments which line the river are decorated with the handsome name of “Marine Parade”. It is the district of commerce and public establishments: Post Office, Courts of Justice, Communal Library, Entertainment Hall, Hotels, two or three large streets parallel to the wharves, and streets running at right angles form the whole network of Wairoa.

Nevertheless these streets are not all lined with houses – was Paris built in a day? But there are some attractive residences indeed, a good number of cottages surrounded by gardens in blossom – where fruit is plentiful in the autumn; and if you add to these small earthly paradises three churches, fine schools, a hospital, a newspaper which skilfully defends the rights of the locality, and a prison to lock away those who would voilate [violate] those rights – or have drunk one too many, you will be forced to admit that Wairoa possesses all the signs of high civilisation…”

Photo caption – “was Paris built in a day?”

Page 10

To add to Fr Yardin’s description, Wairoa in those days also boasted the sevices [services] of a plumber, carpenters, painters, photographer, shoe and shoe-repair shops, doctor, dentist, solicitor, general store, draper, barber, cabinet-maker, bank, leather and saddlery shops, stables where horses or wagons could be hired, jeweller, bushmen, auctioneers and interpreters. It could indeed be said that Wairoa was, for the times, a modern community.

There was also a baker who, besides having a shop, delivered fresh bread daily to hotels, boarding houses, and the more closely populated parts of town. The bread was delivered by horse and cart, and a loud cry of “baker” at each street corner soon drew people out for their daily supplies.

Similar ultra-modern services applied to milk and meat. The milkman, again using horse and dray, called “Milko” at each stopping point and people who needed fresh milk came with their pots, billies or jugs, to be served by the simple and convenient method of the milkman, using a half pint, pint or half-gallon measure to dip into his 24 gallon can. In those days, people were a hardy lot, and if you happened to be squeamish because you [you] saw a swarm of flies depart from your dipping measure as the milkman picked it up – then you didn’t use milk.

The butcher delivered every second day. (He had to “kill” on the intervening day.) Again the horse and dray were his mode of delivery. In a covered shelter hung a small quartered beef, a few mutton and sometimes a pig. On his cart was a large wooden chopping block and as roast, undercut or stewing steak was ordered, out would come the knife and chopper and the order would be instantly fulfilled. In hot summer months flies were a constant companion of the meat cart – but then who cared about an odd fresh “blow”. After all, in hot weather everything perishable had to be cooked immediately. In the summer, corned beef was a popular dish. Being well salted it kept far better. The butcher always carried an array of pickled meats and no doubt, when he finished his rounds, all unsold meat went into the pickle barrel. In those days when refrigeration was unknown, milk and meat could go off in the hot weather in a few hours. So housewives, besides tending to their families, had to constantly keep the home-cooking fires burning.

Photo captions –

Outside McGowan’s Boarding House

All the signs of high civilisation

Page 11

In those early days, fish must have been a large part of the diet of the 500 or so resident population. The river was unspoiled and teeming with fish life. Flounders, mullet, eels, herring and kahawai were there for the taking and whitebait was on the menu every day of the year. Almost every year large shoals of kahawai, possibly pursuing herrings or even being themselves chased by kingfish, would cross the bar, enter the river and proceed upstream as far as the old bridge. The river from bank to bank would become a spectacle of leaping fish, the pursuers and the pursued and into the turmoil hordes of gannets would plummet into the boiling waters for an easy meal. Down by the bar, pipis were available for the taking. Alas, with the rape of our seas by large trawlers with echo sounders and trawl nets, those days will not be seen again. In the 90’s Wairoa had a thriving flax industry and the boats that used the river to bring in freight and passengers generally returned to Napier carrying wool and flax.

When the time came for Fr Lepretre to make his home in Wairoa, he found a pastorate eager for the presence of a permanent priest. In the last century death was a more frequent early visitor to many families. Large families were the rule, and the childhood illnesses of chicken-pox, mumps, measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis and pneumonia were all killers that could take many lives. A resident priest who could give the last rites and say a funeral Mass was a very desirable acquisition.

On the human side, our priest found a hard-working population, little different from today’s people with likes and dislikes, people with idiosyncracies, but with perhaps one major difference. Because the average life-span was much shorter and death a more constant early visitor, people tended to rely more on God in prayer for help than on antibiotics and sulpha drugs. So the original catholic families, whose names are scattered throughout these pages, set to work with a will to build a preysbytery [presbytery] for their priest who had arrived in Wairoa to take charge of the town and a far-flung area on 2nd December, 1894. Later a school would be built for their children, but let a more knowledgeable pen than mine record that story. Max Crarer

WAIROA LIFE 1890’s

1891: Fr Lepretre recuperates in Sydney

1891: O. Johansen paints Wairoa Bridge – 29 pounds

1892: May floods destroy many bridges

1894: Death of Fr Patrick Kerrigan in Napier

1894: FIRST RESIDENT CATHOLIC PRIEST

1894: Typhoid and Diptheria [Diphtheria] epidemic

1897: Fr Lampila dies in France

1897: Blackberry declared a menace

1898: Severe quake topples 300 chimneys

1898: “Tangaroa” makes its first visit

Photo caption – First Wairoa Hospital

Page 12

4 AN OVERVIEW 1894-1993

The sale of Pakipaki land in the early 1890’s disrupted the workings of the catholic Mission. Almost all the Maori community moved away, it seems. The place had no future as a permanent residence. To remain would lead to “sheer loss of time”, as Lepretre explained to Redwood. Lepretre finally folded his tent at Pakipaki sometime in August, 1894. On 15th August, he baptises three girls in Napier, probably pupils of the Providence. One is Mary Harata from Whakaki near Wairoa. His next baptisms are at Ruakituri on Wairoa’s border with the Urewera. For the rest of the year, he is clearly based in Wairoa.

What moved him to come north to Wairoa was the sudden death in Napier of Fr Patrick Kerrigan the assistant priest there. Kerrigan was a Derry man who had studied at Dunalk [Dundalk]. He had achieved much since his arrival in New Zealand in 1875. In Napier “he was a boon and a blessing to Fr Grogan the parish priest,” his panegyrist told the congregation. In fact “his zeal brought him to a premature end.” Fr Kerrigan had been called to Wairoa to attend Mr Harmer in his final illness. The stress and strain of this pastoral visit seems to have taxed his health. When finally he arrived back in Napier he contracted a serious chest condition and died within a few days on 6th August.

His death was surely a factor that helped Redwood make the decision to ask Lepretre to take up a permanent residence in Wairoa. Napier parish would no longer have to serve the needs of another somewhat distant town.

In his letter to Lepretre of 27th November 1894, Redwood puts things clearly.

“…You ask that your residence may be transferred to Wairoa where you could have charge of both races. Having considered maturely together with Very Rev. Father Provincal your request and the reasons alleged in support of it, I have determined to accede to your desire and I hereby appoint you to the charge of Wairoa without separating finally that district from the territory assigned to the Society of Mary but removing it from the charge and juristiction [jurisdiction] of Napier.

Photo caption – Peter Lepretre

Page 13

…Hoping your ministry will be fruitful to a very consoling degree in regard to both races and imparting to you and your people my best blessing.

I remain…”

It is clear from this letter that Wairoa does not become a parish in the strict cannoical [canonical] sense in 1894. It remains a “Mission” with a “Mission Rector”. It is clear al[s]o that Lepretre took the initiative in suggesting that it would be good for him to live in Wairoa and to serve both races. We know from earlier letters that he had a soft spot for the Maori people of Wairoa. His readiness to look after both races says something about [t]he man. He felt that an integrated ministry could be achieved and to a high degree he did achieve this in his time. He was in sole charge in this isolated part of the mission field and he was clearly persona grata to both Maori and settler. But his earliest enthusiasm and expertise had prepared him to work among the Maori people. His knowledge of Maori language and customs was his position of strength in ministering alone to both races for the next 26 years.

In the 1950’s Mrs Hector Murdoch identified the house that Fr Lepretre lived in when he first settled in Wairoa. It was the home that the Aldridge family grew up in and is still remembered by Madge Cooper, one of the Aldridge children. The photo of it you see here was taken in 1953 but the house has since been demolished. This house of course, was no more than his base when he was in town. He was still an intinerant [itinerant] missionary responsible for a large patch of territory. A few years later he summed it up.

“Limits: for White population, from Esk River south to Reinga north – 80 miles long; east to west about 40 miles.

Maori population, from Dannevirke south to Tiniroto north, 200 miles long; east to west about 40 miles.

White population 140

Maori population 150”

These were the Catholics known to him. It was a large area to cover for so few people. But cover it he did.

In his first year, he visited Pakipaki at least five times but on each occassion [occasion] only one baptism is recorded. A remnant of his flock must have lived in the area. It is the year that his new presbytery is being built in Wairoa. The year after its opening, he seems to have covered the highways and byways of the rugged hinterland of Wairoa. In a latter report to his Marist Provincial he listed the villages he was accustomed to visit in rotation on some week-days to celebrate Mass:

Photo caption – First rented residence, 1894

Page 14

Tangohio [Tangoio], Mohaka, Nuhaka, Whakaki, Te Hatepe, Ruataniwha, Te Uhi, Te Reinga, Te Otutoko, Paeroa, Matoitoi, Tukemokihi, Opoiti, Whakamahi, Waiparipatu, Kihitu and Patunamu. In winter the unmetalled tracks were impassable. In a journey to Tukemokihi on one occasion it took him and his guide three hours to go six miles – “in places the track was no more than two feet wide and bordering along drops of hundreds of feet.” Meals, when fortune favoured, could be a piece of boar but “rather too often apiece of heavy bread soaked in tea.” With a tent to sleep in bodily needs were provided for.

In 1897 he pays a lot of attention to his southern outpost Makirikiri, south of Dannevirke. There are numbers of baptisms on his visits in March, July and August. In 1898 he is back there on at least four occasions. Given that Makirikiri was 200 miles from Wairoa and that travel in and out of Wairoa in the 1890’s was unpredictable, Lepretre must have been away from his comfortable mission area for long periods. However, his visits to Pakipaki mission become less frequent and help is given by the Marists stationed at Otaki. In particular Delach, who knew the area well, made reguar [regular] visits to Makirikiri, Pakipaki, Waimarama, Moteo and so on. For Lepetre’s [Lepretre’s] sake, this was a good arrangement. His health which had earlier required a period of rest in Sydney was again a matter of some concern. From the early 1900’s, his work was largely centred on Wairoa, although he had regular contact with St Joseph’s Providence in Napier, as a kind of chaplain figure to the Maori girls there. He would now have more time for the “tasteful supervision” of the presbytery grounds.

In June 1906, Archbishop Redwood came to Wairoa. There are no confirmations recorded for this year. He may have been making a relaxing holiday visit. In five hand-written pages he has left us a detailed account of a two day excursion to Lake Waikaremoana.

“On Tuesday 6th of June Father lepretre S.M. and I started from Wairoa for Lake Waikaremoana. We had a fine comfortable buggy and a pair of good horses in perfect condition which Fr Lepretre drove in right good style…”

Photo caption – Poyzer’s Hotel

WAIROA LIFE: 1900’s

1904: J. Bowie appointed Head master of Wairoa School.

1906: Telephone exchange opened.

1906: Fr Lepretre takes Archbishop Redwood on a two day tourist trip to Waikaremoana.

1907: Mr Summerfield forms Ruataniwha Road.

1909: First Frasertown Bridge opened.

1909: Mary MacKillop, Foundress R.S.J. dies in Sydney.

1909: Wairoa Town declared a Borough.

Page 15

It is interesting reading, this pleasant interlude in a busy life. They were back safely in Wairoa by 6 p.m. Thursday.

“I shall long remember with pleasurable feelings this very successful excursion; nor can I speak too highly of the beauties of Lake Waikaremoana. They fully justify its great reputation.”

It was probably late in the year that a plan was being considered to give Lepretre a trip to Europe, for the sake of his health. The Marist authorities in Lyons were not enthusiastic to begin with but the New Zealand Provincial, Thomas Devoy, did not give up. In September 1907, the Superior General, Jean-Claude Raffin, finally authorised the visit. He mentions the need for a replacement in Wairoa. Lepretre was absent from Wairoa from 27th January to 29th November 1908. His place seems to have been taken by Nicholas Binsfield. He was in Hawkes Bay 1904-10, residing at times in Meeanee and at other times in Napier. Francis Delach also spent some time in Wairoa that year. We know little of Lepretre’s return visit to Europe. There is a reference to it from Fr Raffin in a May letter. “Good Fr Lepetre has arrived here after having had the consolation of visiting Rome, having an audience with the Holy Father (Pius X) and receiving the Apostolic Blessing.” He has seen a doctor who has prescribed treatment that gives every hope of restoring his health.

We have no evidence to show that Lepetre returned to visit his family at “Les Chauvinieres”, but it would be almost unthinkable, not to say inhuman, that he would not have done so. When in a few years, he undertook the building of St Joseph’s School and convent, we know that he was given authority by his Provincial to use a family legacy to help with finances. Perhaps this was the family’s response to his visit and his opportunity to explain the needs of his Mission of Wairoa. The final cost of school and convent seems to have been £2,400. The Lepretre family legacy contributed a generous £700 to the project.

Lepretre seems to have returned with new energy. Marist Home Missioners, Fr O’Connell and Kimbell, were engaged to enliven the faith of the St Peter’s community. It succeeded well and did much good. “Several stray sheep have returned to the right path and continue to stay on it.” While there was some benefit to his Maori flock, he proposed a special Mission for them later and

Photo caption – The famous Kiwi

Page 16

hoped Claude Cognet would come from Otaki to be the preacher. In his day to day letters to the Provincal, he usually ends by “hope you are well”, but on an occassion [occasion] at this time he hopes “you are as well as I am”. Then comes the building of the convent and school. Some months after the official opening, there seems to be talk of Lepetre’s moving from Wairoa. “You mentioned that Meeanee would be better for me than Wairoa or Pakipaki” he says in a letter to Regnault. “If we get fair support from the Bishop I do not mind staying at Pakipaki.” But good religious that he is “of course please yourself about this matter.” The decision was to leave things as they were. It is about this time it seems, that the big, black thoroughbred – so it is said – Kiwi, joins him. There were £35 needed for a horse and harness. Kiwi is one of the strong memories of senior parishioners today. Harnessed to the smart gig, Kiwi and his owner became part of Wairoa. Rene Gray remembers having many Kiwi-powered rides.

In mid 1913, there are signs that the isolation of Wairoa is beginning to tell. He is nearing 60 years of age; he is five busy years on from his European sojourn. He writes to Regnault:

“I was very sorry I could not go to Meeanee, when you were there. I miss all the little occasions to meet other confreres, which would be a great treat for me. I was in Napier last week for a day, it is only the second time I could go out of Wairoa, this year.

I feel at times that I could run away from Wairoa as far as possible, to the Antipodes of it, in Spain. Barcelona would be near enough. It is a good thing I am poor, for if I had the means, I do not think I could resist the temptation of clearing out. Twenty years in prison is a long time.”

In October he reports bad health and having to take to his bed with “un gros rhume.” He had recently had bad experiences with “la bar” in his travel arrangements. But life went on.

In early 1918, there was an interlude in Lepetre’s isolation that must have pleased him. On 2nd January a group of 12 Marist seminary students from Greenmeadows came to spend the summer in Wairoa. The “Wairoa Guardian” of 4th January reports:

Photo caption – “Tangaroa” crossing “la bar”

WAIROA LIFE: 1910’s

1910: Disastrous Cyclone wreaks havoc.

1910: “We are completely isolated. We will soon have to resort to aeroplanes.” Lepretre, 11.4.1910.

1910: First motor registration in county – J. Hunter Brown

1912: Wairoa Hospital and Charitable Aid Board constituted. Wairoa now served from Napier

1913: Wairoa Borough generates electricity.

1914: Outbreak of Great War.

1914: Wairoa’s first freezing works.

1916: Red-triangle markers mean no faster than 8mph when passing.

1919: Death of Fr James Taylor in Townsville.

Photo caption – “Tangaroa” crossing “la bar”

Page 17

They came and returned on the “Tangaroa” and stayed in all for 10 weeks – somewhat longer than was planned. Lepretre must have enjoyed having these aspiring Marists coming to daily Mass and bringing a measure of youthful enthusiasm into his life. They had the use of a boat to fish on the river; they planned an excursion to Lake Waikaremoana. Even Tommy Corkill lent them “an old cart and horse without shoes”. A wagonette and two horses were hired from H.B. Motor Company and a lucky duo or trio had the luxury of Kiwi and gig. Another day two adventurous spirits borrowed bikes to visit Morere hot springs and found the roads exceedingly rough. It was “a most enjoyable camp in altogether new surroundings.” So enjoyable was it that no one had checked the date for their return. One day Fr Lepretre sent a message down to the camp by some lad on a bike – who was he – saying a phone call had to be made to the seminary. Tom Heffernan phoned “and got a bit of a blast for not coming home.” He was equal to it: “Father, had we come home unannounced and unexpected what sort of reception would we have got?” “Oh, yes,” came the reply “I suppose it’s our fault but come home as soon as you can.” Dutifully they broke camp only to find “la bar” was favouring them. They had to be billeted with Catholic families for another week. Had not the shipping firm Richardson’s hand been twisted by parliamentarians and public works men waiting in Napier to go to Waikaremoana to investigate the hydro-electric scheme, the “Tangaroa” might have been delayed longer. The students’ assessment was definite. “That was a glorious camp.”

Photo captions –

“A large party of Meeanee Mission students has arrived to spend the summer vacation in Wairoa bacthing (sic) [baching] in a dwelling on Kopu Road south.”

Students camp, Kopu Road, 1918

St Peter’s Church

Page 18

On 27th July 1919, Fr James Taylor died in Townsville, Queensland. He was a victim of the post-War influenza, just 44 years of age. James was born in Wairoa in 1875. At the loss of both of his parents, the McGowan family took him in. They saw the promise in him and, at the right time, Lepretre made arrangements through Fr Yardin for James to attend St Patrick’s College, Wellington. Later he did his priestly studies with Marists in Paignton, England, taught for three years in America and was ordained after he had returned to New Zealand. His death came after he had spent two years in Australia in the work of preaching parish missions. He had a special empathy for the poor and sick and a great patriotic heart. A poem he wrote, “Good-bye New Zealand” begins:

“My island home, dear land of peace and joy

My childhood’s nurse, my youth’s wild passionate love.

Thy scenes which gladdened, soothed me as a boy

Are not to cheer my manhood – doomed to rove.

Too well I loved thee, something like a mother –

Death early tore her from my lonely heart.

It searched in vain the wide open world for another

Its filial love to her it did impart.

I well remember, even as a child.

How close I clung, and even loved to be

In some lone spot of beauty, green and wild.

Or else in rapture by the queenly sea.

There’s not a leaf, a tree, a flower that blows

Upon thy bosom, natural garden fair.

But round my heart was wound a tendril close

To rend – to sever which – I cannot bear.”

James Taylor had ever remained a Wairoa boy, the first vocation to priesthood from Hawkes Bay. The Catholic community would have felt his untimely death deeply. Mr and Mrs McGowan paid for the statue of St Peter Chanel as a memorial to James, and also the plaque which still has a place in St Peter’s Church. People still remember that Peter Chanel and Therese of Lisieux were two saints Fr Lepetre spoke about most often.

With the 1920’s, seven years have gone by since there was a suggestion that Lepetre move out of Wairoa. It was not to be By September, 1921, Celestine Lacroix is administering St Peter’s Wairoa. What brought about this change is not clear. There may be archival records waiting to be uncovered. It is sometimes said that Lepetre resigned his charge of St Peter’s. Another report says “since 1922 he has been devoting himself exclusively to the Maoris of this vast district.” Whatever the reason, the result is the same. His responsibility now is pastoral care of the Maori people. It is interesting

Photo caption – William and Jane Moroney

Page 19

to note that on the Provincial Finance documents for October, 1921, the title Parish of Wairoa is used for the first time. It will now have a parish priest – and an aging missionary apostolic, with limited jurisdiction, trying to meet the needs of a scattered Maori flock. Is there some irony in a decision that was made in 1923. The Pakipaki mission was given back to him and he had to take up again the torturous journeying in and out of Wairoa.

Since 1909 Lepetre had had few dealings with Pakipaki. He would have known no doubt that Urupene Puhara, son of Puhara Hawaikirangi , the original friend of Lampila’s first Pakowhai mission, had legally deeded to the Church one acre of land around the church and mission house at Pakipaki. Was he present at Urupene’s tangi when he died in 1914? We do not know. However it happened, people had migrated back to Pakipaki and there would have been old friendships to renew. A family that should be mentioned here is the Moroney family. William and Jane Moroney ran the large boarding house at the Pakipaki settlement. It provided permanent rooms for workers at Borthwick’s Freezing Works which opened about 1906. Casual accommodation was also available. It was an oasis of faith and hospitality at Pakipaki and a home away from home for itinerant Maori missioners. William had hoped to set up a hotel as his brothers Dan and Mick had done at Waipawa. The three brothers had come from Ireland in the 1870’s. The Maori people, however, did not allow a licensed premise at Pakipaki.

Once William had spied out the land on his arrival in Hawkes Bay, he sent to Ireland for his sweetheart Jane McShane, to join him. She was 18 when she boarded the “Helen Denny” bound for New Zealand. Accompanying her were one of her sisters and a friend, Agnes Shelvin. Agnes would later marry Edward Winter. They became the parents of Ag and Mag Winter, well known to earlier Wairoa generations. One of Jane and William’s daughters, Genevieve, married Paddy O’Kane. They farmed at Ardkeen and Paddy later became a Member of the Legislative Council. After Mass on most Sundays, the O’Kanes joined the Winters for the Sunday meal.

When Lepretre resumed the pastoral care of Pakipaki, he visited it every month. The Moroneys were given advance warnings of his visits. He would go by boat to Napier and by train to Pakipaki. One of the nine Moroney children would wait at the station and carry

WAIROA LIFE: 1920’s

1920: Archbishop – not in order for our children to attend Sesame School.

1921: Cellstine [Celestine] Lacroix is administering St Peter’s

1923: Lepretre responsible again for PakiPaki.

1925: James Hickson now Parish Priest.

1927: First exploration for oil at Morere

1928: Gala opening of St Therese’s

1929: First electricity from Tuai.

1929: Radio 2ZP Wairoa on air.

Photo caption – Hato Hohepa Providence

Page 20

his case to the house. He would be treated right royally. All religious who visited the Moroneys were served off the round dining table in the front parlour. This table is still in the possession of one of the daughters. By the numbers of Baptisms Lepretre performed there in the ’20s, Pakipaki had become alive again. It was quite a village with a bakery, a post office and a billiard room. In 1927 Lepretre turned 70. He would have welcomed Granny Moroney’s hospitality. Nor was Jane’s kindness forgotten. When she died in 1937, her motherly care of the priests was acknowledged. A solemn Requiem Mass was celebrated in the Immaculate Conception Church, Pakipaki. A choir from St Joseph’s Maori College came to sing and her casket was draped with a woven Maori mat.

At 70 years of age, Fr Lepetre was not yet ready to call it a day. There was a church to be built at Paeroa, Ruataniwha Road. It had to be built so that he was assured that his missionary labours of nearly fifty years would not have been in vain. The story of St Therese’s church is told elsewhere.

Photo caption – Hilda Morrell, Pa Tanatia, Mina Rangi Terito, Peter Morrell Snr, Peter Morrell Junior: Front: Mereana, John and William Morrell

Page 21

PETER THE BUILDER 5

SECTION A: ST PETER’S PRESBYTERY

Thomas Lambert tells us that Fr Reignier had a basic wattle and dab [daub] hut set up for himself on the north side of the Wairoa river, opposite the Clyde Hotel. This served him for the times he needed to prolong his visits to the district. Outside this hut, he planted a sweet brier or dog rose imported from France. The rose finally spread to noxious weed proportions. It rivalled but ultimately has not outdone Rev. Hamlin’s blackberry. After Reignier’s time, the hut no doubt disappeared, but it can claim to be a first shelter for a Catholic priest.

Archbishop Redwood formally appointed Fr Lepretre to reside in Wairoa in a letter dated November 27th, 1894. The need for a priest’s residence was explicitly mentioned in this letter. For some years past Wairoa had been seen as an adjunct of Napier, where Fr Michael Grogan had been in charge since 1884. In describing Napier in his 1887 “Sketch of the Work of the Catholic Church” the Archbishop ends by saying: “Besides Napier proper there is a nice little church at Wairoa, across the bay about sixty miles from Napier and a small congregation attend monthly.” It is clear, however, that this small congregation was not without hope of having a resident priest one day. Money was already being put aside, as the Archbishop was aware of in his letter of appointment.

He makes the point:

“With the money already collected for a priest’s residence in Wairoa and some other contributions, you will be able at an early date, I hope, to erect a comfortable residence in your new district.” The money in question was held by Fr Grogan conjointly with members of the Wairoa congregation. “Fr Grogan will be glad to have the charge of Wairoa removed from his shoulders”-

Fr Patrick Kerrigan, his assistant, had died suddenly the previous August and had not been replaced. And no doubt Fr Grogan would be very happy to make over the money “so that you may set about building the residence without unecessary [unnecessary] delay”.

With these instructions and information in mind, the young Lepretre was thrown off the deep end into his first building venture. By all accounts he was well supported by the local community and all the preliminaries for a new building were quickly attended to. Mr Robert Lamb of Napier was engaged as architect, but he did not live to see the residence built. As the “Wairoa Guardian” reports … “we believe it was the last building this clever architect designed”

Page 22

Another architect, Mr Finch of Napier, was called in to see the job completed. Mr R.A.Gardiner a local contractor, “carried out every detail with splendid results.” Another local Mr McGowan, did the concrete work and bricklaying, “and not only did he build the chimneys, but also made the bricks, which says much for the nature of the clay to be obtained from the Wairoa flats.” Another local tradesman, Mr Johansen “executed the plumbing work and no one could wish for better workmanship than is here displayed.” Painting and decorating were in the hands of Mr Robb, our local house decorator and photographer. That he has excelled himself is not saying too much.”

A year after Lepretre’s arrival, almost to the day, the new residence was ready. “Wairoa Guardian” of December 7th 1895, under the heading “The Home of Father Lepretre,” describes in extravagant Victorian detail each of the six rooms in the new house – “one of the prettiest houses in Wairoa.” Take the hall for example, from which all six rooms lead.

“Soft reflections from the crystal lights blend harmoniously with the wall paper of light blue and pink panels strewn with dark brown flowers. A linoleum dado, in colours of blue and brown, heightens the effect… The ceiling is flatted in delicate shades of pink and salmon, whilst the double moulding is picked out in tones of amber, azure blue, gray salmon and light pink. The floor is mahogany stained on either side, the remainder covered in linoleum in colours to suit the surroundings. Persian mats complete the furnishings of the hall.” Was Paris built in a day!

All six rooms were 11 feet in stud and “ventilated on the most approved principles.” The doors of kauri, with rimu panels, were massive and handsome, with black and gold fingerplates. Each of the six rooms – drawing-room, study, bedroom, bath-room, ideal kitchen and servant’s bedroom – is described in detail. No reader’s imagination could resist the stimulus of such fulsome reporting. Take the study-room for our visual delectation.

“The study on the right-hand side of the hall, is also a cheerful, cosy room. Here the decorator’s art has been exercised to more useful effect. The window, a large double one, is hung with lovely lace curtains, draped with a valance of choice art muslin. The ceiling is flatted in shades of pink and azure blue, and the moulding in dark pink, azure blue and wild rose. The effect is dainty and suits the colouring of the wall-paper, which has a cream ground luxuriant with running flowers in a shade of heliotrope. The mantlepiece is varnished rimu picked out with gold, and the effect is bright and cheerful and when the open fireplace is filled with crackling logs, the brightness will be intensified. The linoleum is a new design in dark heliotrope and deep cream. The effect of floor covering, wall-paper and ceiling is very pleasing and restful to the eye. The furniture is in keeping with its surroundings, also the pictures, while the numerous well-filled book-shelves speak for themselves as to the nature of the kindly Father, their owner.”

Page 23

Lest the imagination be cloyed by an excess of visual imagery, a detail or two of the other rooms complete the [Provincial]picture. The mantelpiece in the drawing-room, all in New Zealand woods, was a masterpiece of the carver’s art, not too heavy in design and yet with a grandeur in every curve and line which was very noble. In the bedroom, by contrast, the mantlepiece was in a quaint design of rimu with honeysuckle panels. There was a handsome coverlet for the bed composed of hundreds of pieces of silk and velvet The bathroom, favoured with the first peep of day, was papered with washable paper of ivory-white adorned with sage green floral design. The ideal kitchen was fitted with one of Shacklock’s Orion ranges with boiler and latest improvements. By contrast with what many home owners provide for the servant – a box of some kind – the servant’s bedroom in this house was light, airy and well-appointed.

The plaudits having been paid with generosity, the hard realities of life were sounded in the final paragraph. “A bazaar will be held during race week next, in aid of the fund for building the presbytery.” So the money already collected and the “some other contributions” mentioned in Archbishop Redwood’s letter, were not sufficient to pay for “one of the prettiest houses in Wairoa.” In all his time in Wairoa, Fr Lepretre will never be free from fund-raising activities. Bazaars and concerts were the favoured money raisers.

The race week bazaar was typical of bazaars over the years. It was the culmination of long preparation with generous help from Napier people and notable efforts of the pupils of the Napier Catholic school. At 3pm. on a February Monday afternoon Mr J.Powdrell, county chairman, declared the bazaar open in the Jubilee Hall. Mr Powdrell said he was pleased to open the bazaar. People needed their minister to “keep them in the proper path” and he needed a house to live in. Any spare cash those present had, could not be better employed than in patronising the many stalls for the sake of the cause. For his part, Fr Lepretre thanked the ladies who had contributed to the “grand display.” They would be anxious “to try their powers in the way of extracting coins from those present.” He would delay no longer.

About 300 supporters paid for admission on the first day and the bazaar ran for a further two days. The returns from the stalls and the good people organising are worth noting

Stall No. 1: Mrs Poyzer and Mrs Harmer, assisted by Mesdames Williams and Pearse and Misses Allen, Carroll, Pearse and Keefe. They raised £51.5.11d

Stall No. 2: Mrs Torr and Mrs Gilligan, assisted by Misses Jeffares, Cleary and Hawkins. They raised £45.11.9d

Stall No 3: Mrs Moloney assisted by Misses Hawkins and M. and L. Moloney. They raised £40.16.9d

Stall No. 4 (refreshment): Mrs J.Mullins, assisted by Mesdames P. Mullins, Stairmand, Strasburger and Misses Coughlan and Strasburger. They raised £9.2.7d

Page 24

Mr J. Fitzpatrick ran the shooting gallery, Miss Lawton the wishing well and Master Swiggs and Winter the lucky bag. After expenses, it was gratifying to find “a substantial balance of £178.2.8d available for the object in view.” So the first venture of “Peter the builder” came to a happy ending, with the support of great numbers of the townspeople of Wairoa. One might suggest that a tradition began with that first bazaar which has continued to the present day. A little pars [para?] in the “Wairoa Guardian” 18 months or so after the bazaar adds a final touch to the new residence.

“The grounds of the Catholic presbytery, under the tasteful supervision of the Rev. Fr Lepretre, are now looking in splendid condition. The whole front portion has been laid out in flower beds, most judiciously arranged and in a month or so should be a blaze of gorgeous hues. The place reflects great credit on Father Lepretre – it excels everything of the kind in the country.“

Page 25

SECTION B: ST JOSEPH’S SCHOOL

The first mention of a school in Wairoa that Thomas Lambert (“Story of Old Wairoa and the East Coast N.Z.”) could find was in 1859. This was when the Provincial Council of the day voted £50 in aid of education in Wairoa. A small school certainly existed in 1863 with fewer than 30 pupils. But teachers came and went and there were times when Wairoa had no trained school teachers.

By 1904 however, schooling was a stable fact of life. The Wairoa District School was well settled near the present Presbyterian church with three classrooms and 171 pupils. This was the year that Mr John Bowie B.A. became the headmaster. Perhaps as many as 40 children at the school were from Catholic families. In August 1909 however, these buildings which were already quite old, were destroyed by fire. Pupils were dispersed to other sites for their schooling.

Mr Pat Helean has left us the information that he was a new entrant at the Wairoa school in 1909. After the fire, he was one of the several who found a place in a private school in Mr R.J. Pothan’s house in Paul Street. This school is one of interest to us. Mr Pothan, whose engineering and machinery shop was located where New World is found today, had two daughters Freda and Rene. The Pothans seem to have been rather protective parents. A contemporary of the two daughters described them in all charity as “different.” At the time of the fire Rene and Freda were already in the care of a governess-teacher Miss Huscott. A few other invited children it seems, came to the house to benefit from Miss Huscott’s schooling. In a letter of September 1st, 1910, Fr. Lepretre refers to “Miss Huscott of the Bambino School.” Whether this is its official title is not clear. What is clear is that Miss Huscott wants her Bambino school to keep going.

“Miss Huscott of the Bambino School is trying to get some reason to continue her school even when the Sisters will be here.”

Fr Lepretre to Dean Regnault, 1.9.1910

Photo caption – RJ Pothan

Page 26

and Mrs Pothan does too. So much so, that Fr Lepretre is aware of Mrs Pothan’s determination to get another teacher should Miss Huscott decide to move on. In the Booklet produced for the 75th Jubilee of St Joseph’s School 1986, we read:

“Miss Huscott was the first to suggest that a convent and school be established, and Fr. Lepretre S.M., the then parish priest, was very enthusiastic as were the Parishioners when the idea was put to them.”

It is difficult on evidence now available to verify these facts as given in this statement. Writing to Dean Regnault on October 15th, 1909, Fr Lepretre makes the earliest reference to a school that I can find. He is speaking of the precarious state of his finances.

“I have only what I receive from the Propation of the faith: this year I received £28.15.0. All of that has been spent.” Then he outlines some improvements that are needed. “A school is equally necessary but to be able to begin this venture I would need to have at least £1,000 sterling.”

So two months after Wairoa District School was burnt down the need for a Catholic School is mentioned. The disruptions caused by the fire might have been a factor in a heightened interest in a Catholic School. A Catholic school system had of course been well set up throughout New Zealand by 1909. This was a response to the Education Act of 1877 when State-funded education became, by law. Free, Compulsory and within certain hours, Secular. One of Archbishop Redwood’s most important initiatives for his large diocese was the establishment of Catholic schools. It is fairly clear that, at the time we are speaking of, the Catholic people of Wairoa were hopeful of having a school for their children. Whether Miss Huscott was the prime mover remains unclear.

By May 1910, things have developed. Dean Regnault, who became Provincial of the Society of Mary in 1908, is making his first visit to Wairoa. In a letter to Archbishop Redwood written in Wairoa, he has this to say:

“A week ago. I made my way to Wairoa for the first time. It soon became evident to me that a strong agitation for a school had taken a firm hold of the people but the Parish Priest was convinced that they were not prepared to make the necessary sacrifices and that the scheme was premature.”

Photo caption – Archbishop Francis Redwood

Page 27

So much for the reported enthusiasm of Fr Lepretre to Miss Huscott’s reported suggestion that a school be established. Dean Regnault gives the Archbishop a full account of events that took place while he was in Wairoa. A meeting about the school was held after Sunday Mass. The main points raised were finance for building, future support for the school and possible number of pupils. Fr Lepretre thought “40 descendants of European parents and from 15 to 20 Maoris could be gathered together.” Dean Regnault was amazed at the tone of the meeting. “I have seldom seen a meeting so enthusiastic or parents so anxious to provide their children with a good Catholic education …. Fr Lepretre has now caught on the enthusiasm. I have to restrain him otherwise he would make a start at once.” The important matter of staffing the school was not overlooked. Dean Regnault took the matter up with the Archbishop.

“If your Grace approves of the work, an application will have to be made to some Religious Order. I understand from Fr Lepretre that he has given some kind of promise to the Sisters of St Joseph, Meeanee. He has a preference for that Order. These Sisters in the South Island are doing excellent work, equal to that of any other Religious Order, and I think it would be a great boon to them to have another house in the neighbourhood of Meeane [Meeanee] where they seem to be somewhat isolated. If your Grace wishes it, I shall write to them.”

His work in Wairoa completed, Dean Regnault left for Meeanee next day. His letter had concluded, “It is raining here very heavily.”

The Archbishop fully approved of all that emerged from the Wairoa meeting. Speaking of the Archbishop’s repIy, Dean Regnault was able to say:

…. “our choice of the Order was his choice also.”

The Archbishop added that the Sisters of St Joseph had promised him a community whenever he would want one. By the end of May the stage was set for the Catholic people to have their school. Extant plans and specifications were suggested to save money. People needed to be appointed to “canvass the district for subscriptions” and the inevitable bazaars had to be planned. The Dean himself was encouraging. “I need not tell you that I shall give you all the assistance I can.” No good work however, goes without set-backs. Fr Lepretre’s earlier unrestrained enthusiasm was soon tempered by the practical difficulties of erecting two substantial buildings. In September he is having doubts about finance. He realises that when the sisters come he will not be able to serve the remote areas of Wairoa “and if I am not sent a missionary the district will be neglected.” And he is getting much older, “the years are the cause of it.” Journeys on horseback are increasingly more difficult. Despite such woes, the contract for

Photo caption – Dean Regnault

Page 28

the convent and school was fixed at £1394. With furnishings “it will not go far from £1600.” For the school, the plans for Johnsonville school were used. By late October the foundations of both buildings were complete. A shipment of totara timber was awaited, but “la bar” had delayed its arrival. Mr Allen, secretary, and Mr Taylor, Clerk of Works have a lot to say at meetings and want to control everything. This lack of confidence in the Parish Priest was seen as an insult and Fr Lepretre voiced this and other concerns to the Provincial. The Dean, known for his diplomacy, gave good advice:

“Your men are good Catholics and sensible men. If you put the matter before them in its true light, they will follow your directions.”

So it proved, and the work proceeded amicably. By the end of November the school room was nearly finished. The convent was not to be ready before the end of February. “La bar” continued to be a problem.

The focus now shifts to events leading up to an opening of the school. Sydney is contacted to ask the Sisters to arrive in Wairoa in mid January. Carnival week – races, show, regatta 16-21 January, – is targeted for a bazaar to raise funds.

“We must try to make the opening a memorable event for the sake of the Convent and school and also ask for help.”

Once the enthusasm of the people of Wairoa for a school had been tested and then approved by Archbishop Redwood, Dean Regnault wrote to the Provincial Superior of the Sisters of St Joseph in Auckland on 20th May 1910. He began his letter to Sr Raymond Smith:

“I have Good News for you”

The Good News was that the Sisters who had been at St Mary’s College Meeanee since 1886, would no longer be isolated. There was to be a community of sisters in Wairoa. In his diplomatic style Dean Regnault made his request:

“Now, dear Sister, you must not, you cannot afford to lose this foundation. Kindly write to Sydney at once and tell Rev. Mother to have some nuns ready for next February. They will begin with some forty-five white pupils and twenty Maoris, there is no telling what number they will have before the end of the year.”

Sister Raymond it is worth noting, one of the Pioneer band of Sisters who came to New Zealand in 1883, obviously obliged Dean Regnault and wrote to the Superior General in Sydney. As a result, three Sisters were chosen to begin St Joseph’s School in Februrary [February] 1911. Later in 1910, Fr Lepretre had written to Sydney, asking that the Sisters be

Page 29

in Wairoa in mid-January, 1911. They did in fact, arrive on 26 January.

The three Sisters were all New Zealand born. The Superior, Sr Lucian Brosnahan, was born and brought up in Kerrytown, South Canterbury. So also was Sr Emerentia Kelly, while Sr Xaveria Bailey’s family lived in St Patrick’s Parish, Auckland. It is good to think that we still have links today with these Pioneers, however tenuous, through Sr Molly and Sr Colleen. Sr Molly knew all three of them in Religious Life while Sr Colleen can claim family links with Sr Lucian

Sr Lucian remained in Wairoa till the end of 1917. From then on, she taught mostly in schools in the Coromandel and Auckland areas. On present available information, we are not sure how long Srs Emerentia and Xaveria remained in Wairoa. Sr Emerentia died in Auckland in 1957 and Sr Lucian died there in 1961. Sr Xaveria died in Sydney in 1962. God rest them in all their labours.

Their labours in Wairoa, however, were only about to begin. In December, they crossed the Tasman from Sydney to Wellington and in due course made their way to stay with their community at Meeanee. The final leg of their journey meant crossing Hawke Bay by the trusty S.S.”Tangaroa”. The “Wairoa Guardian” of January 27th 1911, records arrivals of January 26th. It names eighteen passengers and “several others”. The Sisters are named. Another who was named appeared also in the Personal Column as having spent part of his holiday at a Cadet Officers’ Training Camp in the Wellington district. This was Mr John Bowie, who since 1904 had been Headmaster of Wairoa District School. Before many days the Sisters will have reason to be grateful to Mr Bowie.

After a tumultuous welcome at the Wairoa wharf where Fr Lepretre and a large group of parishioners had assembled, the Sisters were driven to their temporary residence. Their convent was not yet ready. Fr Lepretre made the presbytery available to them for as long as that would be needed. It was fortunate that a few years earlier it had been extended by two rooms. There was no long settling-in process. One week after the “Wairoa Guardian” had announced the Sisters’ arrival, it carried this notice: “St Joseph’s School in Queen Street, under the management of the Sisters who recently arrived from Sydney, will open on Monday”:

Photo caption – School, Convent and Church

Page 30

And it did, as the “Wairoa Guardian” of Monday assures us.

St Joseph’s Catholic School opened this morning under difficulties seeing that the desks are on the “Tangaroa” and were taken back to Napier.”

Another trick played by Fr Lepretre’s “la bar.” It was at this point that Mr Bowie came to the rescue with the loan of desks from his school. Perhaps he had shared school experiences with the Sisters as they travelled to Wairoa on the “Tangaroa.” After the August 1909 fire which destroyed the old District School, a new school was built on the present Wairoa College site. When it was opened in November 1910, a speaker at the opening was able to say: “It is the first time the town has had a decent school.” Within a few months, St Joseph’s would provide a second “decent” school, though not completely decent” without its own desks.

In a letter to Fr Regnault on February 17th, Fr Lepretre began:

“The school is now open, all the Catholics except for five attend there. In all, there are 58 children, of whom seven or eight are Protestant and all the others Catholic …The Sisters are very delighted. I must say also that they, all three, are excellent. I could not desire better…..”

But despite such promise, there were clouds of war on the horizon. “But with the school, the war began” Fr Lepretre wrote and the instigators of the war are none other than Mr and Mrs Pothan. They require a school environment consonant with the cultural and intellectual needs of their two daughters. Mr Pothan convened a meeting “in order to discuss the measures to be taken to resolve the matter of the Maoris. They would need a school of their own and a special sister.” Such a proposal was not music to Fr Lepretre’s ears nor to the Sisters. “Fortunately,” Fr Lepretre continues, “not everyone shares the same opinion and Pothan has made himself many enemies.” There were parents however, who did not send their children to the school for “fear that Pothan will not find them worthy of his children.” It is hard to believe that within two weeks of the opening of school the pastor of Wairoa would write:

“If people were to take Mr Pothan’s side, the best thing for the Sisters to do would be to leave to avoid his persecution… He told me he was going to write to the Archbishop and that my days in Wairoa were numbered.”

Of course it did not come to that. Things must have settled down quickly enough. The spirit of St Joseph would have helped sweet reason to prevail. By mid-April plans for an opening of school and convent in May are firming up. The roll has risen to 72 despite Mr

Page 31

Pothan. An extension of the school is needed. So it seems the second room of the original school was not built initially. It is interesting to find that when Dean Regnault said he could not come to the opening in May, Fr Lepretre asked if Fr Taylor his Wairoa protegee [protégé], could come instead. Fr Taylor sent Fr Lepretre the following telegram from Leeston:

“Taylor parochus Leestoniensis si possible adibo cum archiepiscopo” (From) Taylor parish priest of Leeston. If it is possible, I shall come with the Archbishop.”

Did he come? The “Wairoa Guardian” tells all. On Monday 8 May, the “Wairoa Guardian” announced to the local people that “Archbishop Redwood is expected to arrive in Wairoa on Friday, and will formally open the new Convent and school on Sunday next. A confirmation service will also be held on the same day.” An up-date on 12th May advises that the Archbishop, accompanied by Very Reverend Dean Regnault and Fr H. McDonnell, parish priest of Napier, will arrive this afternoon. So Dean Regnault had a change of heart and Fr Taylor missed a chance of returning to his home town. The stage is now set for the grand opening on the following Sunday and what an eventful day it was. In the Wednesday “Wairoa Guardian” following the opening, an amazingly full account of the day is printed. This is in keeping with the reporting practice of the day and especially of this newspaper which is a treasure-trove of Wairoa history. All praise to the staff of that time.

Sunday began with a Missa Cantata sung by Dean Regnault. The choir, under the baton of Mr Horton sang the Mass of St Cecilia. After Mass Archbishop Redwood confirmed 13 boys and 10 girls. The names read like a St Peter’s Parish Who’s Who of the day – Barrett (2), Buchanan, Corkill, Crarer (3), Dillon (2), Finucane (2), Gilligan (2), Hird (3), Johnson, Matthews, Mullins (2), Smith, Taylor, Twomey. It was, in fact, the last time Archbishop Redwood administered confirmation in Wairoa. A formal luncheon followed which was attractively set out in the “Convent schoolroom.”

The blessing and official function began punctually at 2pm. Messrs J.O. Scott and E. Devery had decorated the convent with flags which helped to conceal some unfinished work by the builders. Seated on the verandah in the official party were Archbishop Redwood, Dean Regnault, Fr McDonnell, Fr Lepretre, His Worship Mr. J. Powdrell, County Chairman Mr. J. Hunter-Brown and Mr. J.L .Matthews representing the church committee. The Archbishop, the Mayor and the County Chairman were the speakers and their words are amply reported. The Archbishop was pleased to be here “in the rising town of Wairoa.” The present occasion was “a new epoch in the history of Wairoa.” The Mayor was pleased to see such a large gathering

Photo caption – James Taylor S.M.

Page 32

“Wairoa had a great future – unlike towns that had a mushroom kind of existence and soon were not heard of.” For the County Chairman, it was a great pleasure to be present. He referred to the Christian era of convents and monasteries where the work done promoted later civilization. He paid tribute to Fr Lepretre who was “highly respected by all.” The final word was with the Archbishop who said they “now came to a part of the proceedings that could not well be omitted: an American had said that Money led to the Devil, but it was the very devil to be without it”. (Laughter). On the day £70 was donated with promises of more.

Many gathered in St Peter’s Church for an evening service. Fr Lepretre led the recitation of the Rosary and the Archbishop gave an interesting and vivid account of the Eucharistic Congress he had recently attended. The people were greatly aided by his “beautiful word picturing”. One can but admire the energy and enthusiasm of this man of 72 years. For the Catholic people of Wairoa and indeed for the whole town, it was a day to remember.

So successful was the school that by December 1911 a contract had been let “to extend the school and to add two rooms.” To pay for this an acre of parish land was sold and inevitably, a bazaar and social were organised. By July 1912, the additions were complete and the roll had risen to 88. “So the school did not come too soon as some were inclined to think. We have four Sisters and they are all very busy. They have 17 or 18 pupils for music and also a good number for painting etc. There are no boarders as yet.”