- Home

- Collections

- DAWSON SM

- Pop - Arthur Stowell (1891-1963)

Pop – Arthur Stowell (1891-1963)

Page 2

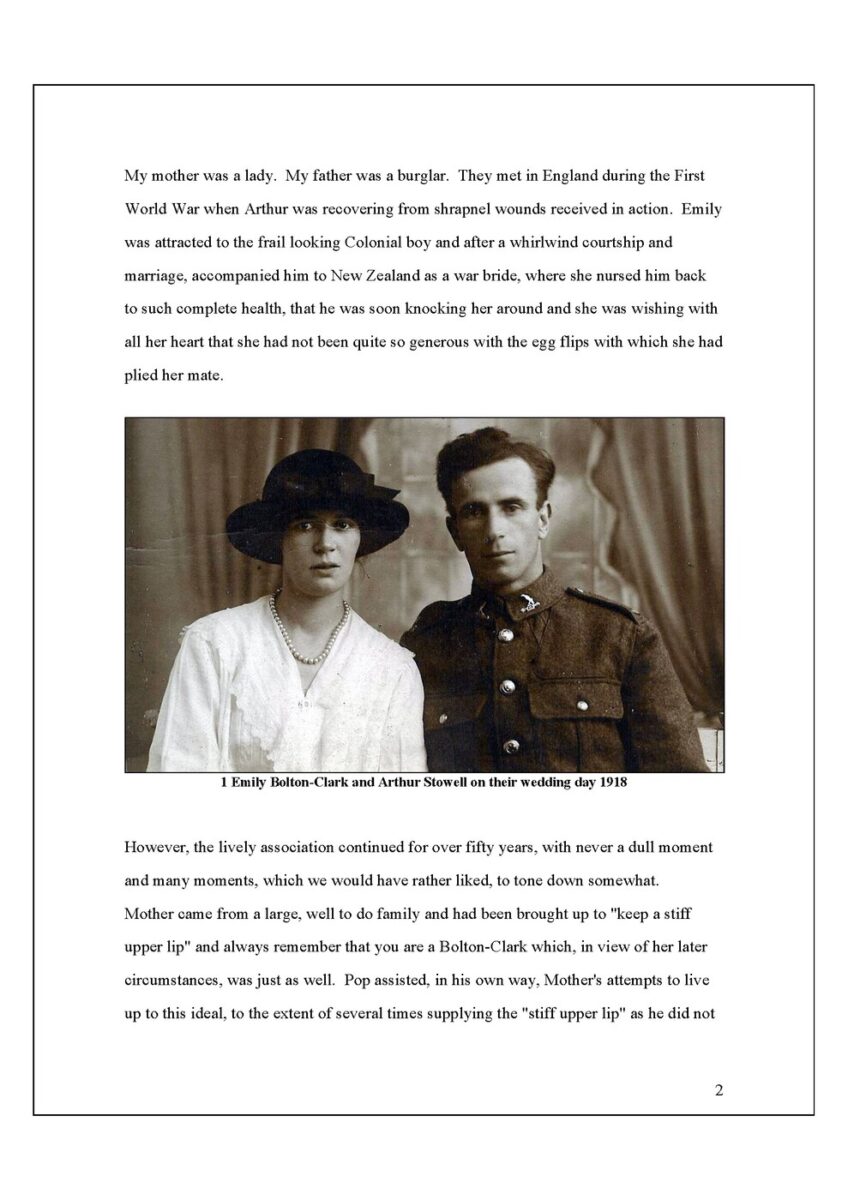

My mother was a lady. My father was a burglar. They met in England during the First World War when Arthur was recovering from shrapnel wounds received in action. Emily was attracted to the frail looking Colonial boy and after a whirlwind courtship and marriage, accompanied him to New Zealand as a war bride, where she nursed him back to such complete health, that he was soon knocking her around and she was wishing with all her heart that she had not been quite so generous with the egg flips with which she had plied her mate.

1 Emily Bolton-Clark and Arthur Stowell on their wedding day 1918

However, the lively association continued for over fifty years, with never a dull moment and many moments, which we would have rather liked, to tone down somewhat.

Mother came from a large, well to do family and had been brought up to “keep a stiff upper lip” and always remember that you are a Bolton-Clark which, in view of her later circumstances, was just as well. Pop assisted, in his own way, Mother’s attempts to live up to this ideal, to the extent of several times supplying the “stiff upper lip” as he did not

Page 3

like to be answered back and of course Mother’s unquenchable British spirit resulted in a head sometimes bloody but always unbowed. She spoke very well, without affectation, and was in spite of a very chequered and enlightening existence, every inch a lady when she died.

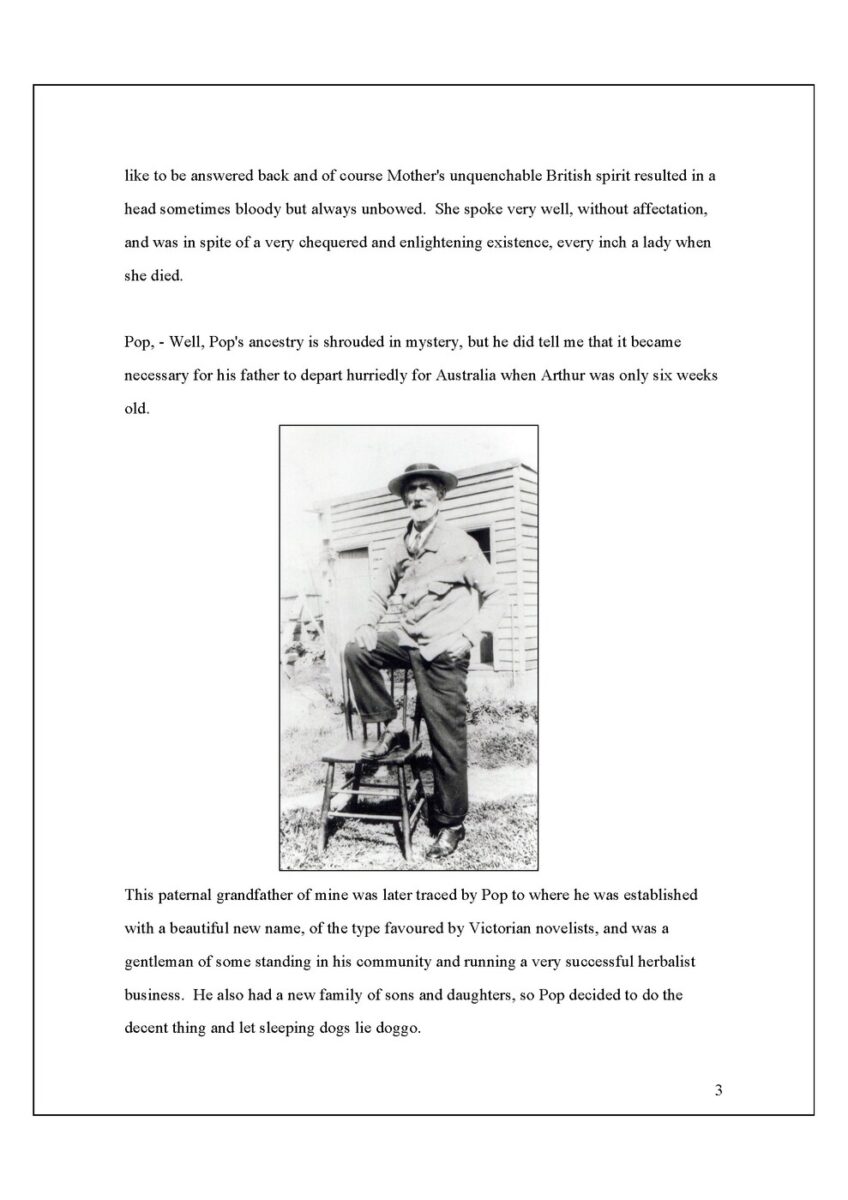

Pop, – Well, Pop’s ancestry is shrouded in mystery, but he did tell me that it became necessary for his father to depart hurriedly for Australia when Arthur was only six weeks old.

This paternal grandfather of mine was later traced by Pop to where he was established with a beautiful new name, of the type favoured by Victorian novelists, and was a gentleman of some standing in his community and running a very successful herbalist business. He also had a new family of sons and daughters, so Pop decided to do the decent thing and let sleeping dogs lie doggo.

Page 4

I hope Dad’s deserted mother remarried, because there were brothers and a sister all younger than Pop and it appears that the early upbringing of young Arthur was left in the capable hands of his grandparents.

Arthur seems to have been a bright enough lad, with strong leanings to poetry and in later years, when he had “a few in” I would sit upon his knee entranced whilst through a, beery haze he recited many dramatic poems, snatches of which I remember to this day. One was: –

“A little boat in a cave

And a child there fast asleep,

Floating out on the wave;

Out to the perilous deep”

The child returned safely to land I know, but the method of salvation escapes me. Also,

“Hark how the wind is roaring

Over the roofs in a pitch dark night”

In this, a man sheltered from the storm under a bush, then,

“Something rustled, two green eyes shone

and a wolf lay down beside me!”

That part always scared the daylights out of me, but later verses allayed my fears, as the man and the wolf huddled together because they were both so scared. In the morning they each went their own way, feeling a kind of brotherhood through danger shared and so not caring to kill each other. I always saw my father in the role of this man, perhaps because the narrative was recited in the first person.

Another was,

“A nightingale made a mistake.

She sung a few notes out of tune.

Her heart was ready to break and

she hid away from the moon.”

Page 5

A sparrow or a wren spoke words of encouragement and the nightingale burst once more into song. All Pop’s tales had a happy ending, though I never did feel that it was quite the thing, in the song of “Tin Gee Gee” to “take down the label from the upper shelf and mark him two and three, and mark the other one, one and nine, which was very, very wrong of me.” I definitely concurred on that last point.

I don’t know quite what Emily expected of life in the colonies, but the arrival at her mother-in-law’s house brought her down to earth abruptly. Perhaps Arthur couldn’t pluck up enough courage beforehand to describe the old wooden shack to which he was escorting his bride. Mother entered, surveyed her surroundings and promptly exited again, announcing that she would not be living there, thank you. Arthur’s grandmother, who lived nearby, had a long talk with Emily and they parted on good terms, but diplomatic relations with the rest of the in-laws were never restored and the young couple departed forthwith to Napier to commence life on a higher plane.

Page 6

Mother had quite a tidy sum of money with which she set Dad up in business and before long they had a house in Wellesley Road, a big white car for Mother and a motor cycle for my father. Kitty was born followed two years later by me.

Life was pleasant apart from occasional squabbles over drink and parties and things went on a fairly seven keel. Mother sang gaily as she flitted round the house in the latest fashion in dust caps and as soon as I was big enough, I would climb my beloved pepper tree in the front of the house and sit there happily watching for Pop to come home from work. We were all well dressed, Mum in the latest flapper styles, including a beautiful feather boa and Kitty and I had a fur coat apiece before we reached school age. There were trikes, prams and big dolls, musical seagrass chairs and a girl to help look after us. Pop, however, spent too much time away from the business in the Club – and things consequently did not flourish, as they should have. Two or three times, when the shop rent was in arrears Mother dressed in her finery and departed to interview the landlord, who was threatening to sue for his rent. She managed, several times, to stave off disaster with promises to see that the business was properly conducted in the future, but by now the writing was on the wall.

Page 7

Mother would return from her visit to the landlord and she and Pop would then have a “ding dong go” about the evils of drink and the folly of letting a good business go to rack and ruin, then things would settle down for a while and Kitty and I were secure in our little world again. We had lovely birthday parties, which were the envy of our friends and picnics on riverbanks and at the sea. Perhaps Pop found it too hard to live up to the standard required of him, because sooner or later the performance would be repeated and the spirited arguments increased in number as the volume of business at the shop decreased.

Mother was not quite alone in the new land, as her sister, whom we knew as Auntie Bill, had come out a little earlier and was happily married to Uncle Alf, who was captain of a coastal vessel, the “Ripple”.

Kitty and I loved Uncle Alf dearly – he had a brown suit and a potbelly and made a great fuss over us whenever he came to visit us. Auntie Bill had lost her first baby, Peter, when he was only six weeks old, but now another baby was expected and there was much happy anticipation, which was as short-lived as the baby itself. Auntie Bill was heartbroken, but Alf had more to bear when he was told that his beloved wife had contracted an incurable infection and could not last more than a few months. He said to Mother, “But it cannot be true! She looks so very well.” Indeed she did look well at first, but slowly she failed and he knew he would soon lose her. In August 1924, the Ripple, went down with all hands and Auntie Bill waited alone for death’s release. Kitty and I were taken to visit her in hospital, but had no idea that it was for the last time. She died in January 1925, taking with her Mother’s last shred of hope and comfort in what was becoming a nightmare world.

After this, things went from bad to worse in every way. I became aware for the first time that Pop occasionally had one over the eight, when I beheld him lying asleep on the bed in his clothes one afternoon.

Page 8

“What’s wrong with Daddy, Mummy?” I asked and she, in a moment of aberration replied,

“Shh! He’s schickered!”

I woke him up by asking in a loud voice, “What’s shickered mean?” and I found out then and there that it meant, “Let sleeping men lie.”

Dad’s drinking was probably not half as bad as we thought, but Mother was so dead against liquor that even the smell of beer could cause trouble in the early days. One night father came home in a merry mood and upon being asked, “What is the meaning of this behaviour?” replied, “Well, it’s your birthday isn’t it?”

Perhaps if he had produced a gift for the anniversary his condition would not have caused so much bitter comment.

My mother received quite a few blows during these episodes and one night I woke in terror to find an argument in stormy progress in my parents’ room where I had been sleeping after one of my frequent illnesses. Pop had his fist raised, when Mother leapt to the bedroom window, threw up the sash and was half way through when Pop reached her. I screamed in fright, and Pop turned to me and said gently, “it’s quite alright Bett. Don’t cry.” – and then returned to haul Mother back into the room, boxing her ears as he did so.

After one of these experiences I said to Mother, “Why don’t you cry?”, because I was convinced that she wouldn’t be hit if she was weeping her heart out, but she just replied that one did not give a bully the satisfaction of knowing that he had reduced his victim to tears.

It is difficult to say whether it was this unquenchable spirit which tamed the tiger, or whether the short iron bar which I spotted under my mother’s pillow did the trick, but after a few years the beatings diminished and then stopped. Perhaps adversity brought my parent’s closer or the business of just scraping a living required too much undivided attention.

Page 9

Fate slung her next shaft, this time in my direction. I developed diphtheria and nearly became one less mouth to feed.

After the tracheotomy, Mother would not leave my bedside, even though there was a nurse on duty all the time. So it happened that one night, when the poor nurse was standing at the end of my bed, nearly asleep on her feet, my mother roused her to say that Betty didn’t look very bright at all. The nurse said, “you worry far too much Mrs Stowell, she’s going to be alright.” “But she’s changing colour!” said Mother, whereupon the nurse rushed for the ‘phone bringing the doctor in double quick time clear the blocked tube and give me another innings.

I was delighted on my return home to find that a new dustbin had been bought as a token of thanksgiving for my recovery. Apparently the old bin had been a subject of scathing comment from four year old Bett for some time. Striking while the iron was hot, or at least luke warm, I asked Pop to build me a summer house, which he did expediently by placing two palings at an angle against the six foot wooden fence at the end of the back yard, with a wooden box for a seat. I sat there happily clasping my doll, while Mother stalked inside in disgust at this exhibition of indolence. Happy days!

Next came brother Ron, who, in view of the circumstances at the time, must have appeared to be one more calamity, but turned out to be a very good idea. My mother had longed for a son in happier days and Kitty and I were ecstatic about our new toy. We all sat on Mother’s bed and suggested hundreds of possible and impossible names, before Ronald Arthur was decided upon. As I too, had started school by now, he became a great little companion for Mother, who was determined to bring him up to be a credit to the family back in England.

When Ron was about twelve months old, the two men came, armed with notebooks.

Page 10

I was sent outside to play while the men proceeded to take an inventory of the furniture and contents of the house and Mother found for the first time that Pop had mortgaged the lot and was now in the process of going bankrupt. The furnishings had of course all been bought with Mother’s money, but she was unable to prove it, so that was the end of an era.

We were told that the family was now poor and that we would have to get used to going without, but the first austerity Christmas really brought our new situation home to us. We had always received loads of toys, overflowing from the pillowslips we hung for Father Christmas, and when Mother said, now Bett, you must not expect anything at all this Christmas,” I smiled to myself convinced that I would wake on the happy morning to the usual mound of surprises. I woke full of hope and expectancy, looked in vain for the pillow slip at the end of the bed and experienced the shock of my young life at finding exactly what I had been promised – nothing!

I was lying there, miserably preparing to cry forlorn teats [tears] of self pity, when I espied, hanging at the head of the bed, a sixpenny Christmas stocking, with an orange tucked into the top. Oh Joy! We hadn’t been forgotten. Gone were all the visions of sleeping dolls, prams and tea sets and the reality of cheap paper comics, little tin dishes and cardboard squeakers restored my world in a flash.

I woke Kitty who was as delighted as I was at this wonderful gift and we stormed into the parental bedroom with cries of joy and delight. What a relief it must have been to them to see how genuinely happy we were. That was our last Christmas in the ancestral home and we started on our series of moves from hovel to shack.

We went to inspect a little old house in Enfield Road, with Mum silently despairing and Kitty and I wildly enthusiastic, saying, “Do let’s come to live here, Mum. It’s lovely!” We went there to live and it wasn’t lovely at all, though we played in the Botanical

Page 11

Gardens and spent hours reading the tombstones in the nearby cemetery and enjoyed a change of school.

After three months, we moved to Cameron Road, which wasn’t so bad – a bigger house, but pretty unkempt. At this stage Kitty and I discovered Sunday school and attended the Anglican one in the mornings and the Gospel Hall in the afternoons – and any bunfights, which were on the go anywhere. We had always gone to Sunday school from Wellesley Road, but our motives were different now. It was quite a job for Mother to dress us well enough to go and whenever we had new shoes or home-made coats, we had to be careful not let Pop see us dressed up, as he would feel that the meagre housekeeping money had been juggled for extras and was quite capable of reducing this allowance. We rarely had a penny to put in to the collection plate, but soon got over the shame of passing it without adding to the contents, when we found that there were other waifs in the same boat. Food was not plentiful and we were really feeling the pinch, but it was not too hard for the children to adapt. We thought bread and bacon fat was a treat. Pop had the bacon, we had a plate apiece of warm dripping and a piece of bread. I don’t know what Mother had!

With the sharp change in our fortunes, Mum tried to abandon all her friends, as she had no desire to accept charity and pride led her to pass acquaintances in the street without apparently seeing them. We soon learnt not to tug her sleeve and say, “Look Mum. Here comes Mrs Archer.”

We [when] she was forced to stop by those determined to be friends in adversity, she pleaded short-sightedness and would make her escape as soon as she courteously could.

This method certainly sorted out the gold from the dross and there was still some very good pals’ left. There were others, who envying some of beautiful linen brought from England by the happy bride of a few years back, would spy, “My Dear, I do love that table cloth. Would you consider selling it to me for 2/-?” and family heirlooms and treasures were exchanged for the price of a meagre meal for five.

Page 12

One neighbour kindly handed over several lots of surplus vegetables and then went into raptures over our huge celluloid doll, named Billy, one of our earliest toys and beloved by all of us. We watched it being given to the neighbour for her little girl, in helpless rage and hated that child forever more. We weren’t beholden to them, but it was quite hard to digest this line of reasoning when eight years old. We were never allowed to let Pop know of these transactions, as it would only spark off a row of a, dissertation on “man’s inhumanity to man”, which was the theme song of the moment.

I think on the whole, the women were the mean ones, as they took advantage of the situation and knew full well the value of their trophies, perhaps even savouring the reversal of social positions. Mother often mourned the passing of her hand made lace table cloths in later years and would say, “You know, May Brown gave me only one and sixpence for that, and it took your Auntie Rose such a long time to make.” Hunger is a hard master. Auntie Rose had died at the age of twenty-six, so to part with her handwork meant that starvation was a very real threat.

One day, Mother gave me a very elaborate gold watch and asked me to take it to one of the jewellers’ shops in town, to see what I could get for it – three shillings! Another meal; another link with – Rose gone forever. I didn’t know it was Rose’s watch, but when I visited Auntie Kate in England in later years, she said to me that it was such a shame that Rose’s beautiful old watch had been lost in the earthquake. I neglected to mention that it was gone before then and I was the one who did the deed.

Page 13

On 3rd February 1931, Kitty and I were at Central School. It was playtime and we were waiting for the bell to ring and so as to be first in line to march back into school, were standing by the wall of the new brick lavatory building. Came a prolonged angry roar, someone knocked the wall down and we were a mass of arms, legs, squeals and bricks. I was on my feet in time to see the walls of my classroom dissolve in dust, with the light swinging madly from the ceiling as it too went down.

The teachers rallied smartly and told us all to sit cross legged on the ground, which most of the children did, whilst howling their eyes out, but I felt I would have a better command of the situation if I remained on my feet. The Headmaster appeared carrying an injured boy in his arms, blew his whistle and all the children ran to him like a wave to shore. As we reached him he shouted, “Go home!” and the wave receded in the direction of the school gate.

We ran home, noting elderly ladies being led from houses and settled on chairs by the roadside, chimneys down everywhere and gaping cracks in concrete houses and the road

Page 14

surfaces. We saw one young couple strolling along chatting as if nothing had happened and decided that they were mad, but perhaps they had nobody else to rush home to.

Quite a few people had cuts and wounds and we did not know what awaited us at home. Mother was standing outside our house holding Ron, when Kitty and I hove into view. Kitty was immediately received by Mother’s one free arm, which left none for me and I can remember hanging back and feeling very sorry for myself, as I was, at that stage living in imagination the life of ‘the little one in between’. The one who was always neglected in favour of the elder or the younger child. How I could find time for such thoughts at that time, I do not know. What a miserable wretch of a child!

Pop had been wheeling his motor bike up the hill when the earthquake struck and at first blamed himself for having a couple of beers on an empty stomach, but was soon able to exonerate himself on this count.

Another was revelling in the fact that the landlord had redecorated the kitchen – dark grey paint below and pale grey above. Ron, aged two, had just had his pants removed and gone to the outside toilet, while mother was mixing a steamed pudding in a glass dish, when all hell broke loose. She rushed to the kitchen doorway, to call – Ron, who met her on the threshold, where she dropped on her knees to hold him. The kitchen chimney collapsed onto the table, causing the glass mixing bowl, complete with pud, to fly through the air over their heads and out onto the back verandah. The bowl did not break, which was cold comfort at the time, but cause for great wonderment and comment upon the pudding’s consistency later.

The family was intact, apart from Ron’s pants, but the house was rather the worse for wear, as the chimney between the sitting room and kitchen had not been boarded over and there was nothing to stop it from collapsing, which it did in both directions, smashing the head of Mother’s sewing machine and her best tea service on one side and quite spoiling the new paint work in the kitchen on the other.

Page 15

We sat on somebody’s lawn and watched the town burning below us. Word of a tidal wave reached us and this worried me more than the continuous earth trembles and I sat on the grass recklessly bargaining with God, promising to lead a life of never ending virtue, if he would just keep the sea away from the earth. Dad took us in turn to the end of a lane where we could see, to better advantage, the shops burning and I was most concerned to observe a string of shoes hanging in a shop doorway being consumed by flames. Buildings were blazing everywhere, but the shoes worried me quite a bit.

Our father made several trips into the house to bring out bits and pieces for us and we were allowed to say what we wanted most of all. I chose unhesitatingly an old scruffy doll, who rejoiced in the name of “Poppy, and a red and white figured dress, which one of our real friends had convinced Mum her daughter had grown ou6 [out] of whilst it was still nearly new. Kitty was brave. She went in with Pop and grabbed a few of her own possessions and pants for Ron’s naked Posterior. I was an arrant coward and refused to go near the house again, as ‘quakes of varying degrees continued all the time and I was sure the few remaining bricks from the chimney would slide off the roof and put paid to Kitty and Pop.

I was all for leaving the place as it was and even Mother didn’t have much interest in salvage apart from a request for the old eiderdown from her bed, as several drops of rain were falling and it would be a shelter of some sort.

We were offered a lift to Taradale Camping grounds by a kindly neighbour and after driving past blazing buildings and over cracked and distorted roads, spent a night there in a tent, before being taken next day to the racecourse at Palmerston North. About this time, it was realised that there was no way of keeping track of refugees who were streaming off in all directions, so orders were given that nobody was to leave in the meantime. However, Mother had spoken to a gentleman from Hawera who offered her his beach house at Ohawe Beach, so after convincing officials that we had no relatives in New Zealand to enquire for us, we were driven through the night to the cottage, which

Page 16

was to be our home for several happy weeks, till Pop, who had returned to Napier as soon as we were settled in, could make the house habitable for us again.

Our stay in Taranaki was our last holiday of any sort for ten years, but it was a complete change for us and the wonderfully kind man who had loaned us his cottage, also told Mother to charge groceries and food to his account at the local store. His daughters gave Kitty and I some of their dresses and a beautiful sleeping doll with a china head, purple satin trousers and green jacket. We loved her dearly and I, naturally, was the one to drop her and break her lovely little head, Kitty’s heart and my own into the bargain. Abject guilt ridden misery!

There were several refugee families staying at Ohawe Beach and a businessman from nearby took us to Tokora School in his car every day. We walked home after school, but that never seemed to bother us, though it was quite a distance. One day, while classes were in progress, we felt one of Napier’s continuing earthquake jolts and the Napierites at the school were outside before the local residents, still sitting at their desks, had analysed the bump.

We played happily in the sand hills, collecting from the rocks prodigious quantities of purple crabs in an old bucket and taking them home to Mother, who did not share our concern for the welfare of these friends from the shore and always told us to return them whence they had come. We swam in the lagoon and sometimes we would stand watching the Maoris launching a long boat to go fishing beyond the breaker line. Later we would see the fish strung up to smoke or dry.

One Saturday afternoon, we gave a concert for our parents in somebody’s backyard and while I dispensed lemonade, Kitty stood up and sang, “Home Sweet Home”, with feeling. I was rather annoyed with my mother, because she seemed to be overcome with mirth – but perhaps she had to either laugh or cry, and chose the former.

Page 17

It was a happy summer for the Stowell children and some of the tension left Mother for a while, as she enjoyed the spell from poverty and strife. The time came though to return to the fray, but the train trip was another thrill, terminated by a reunion with Pop on the station platform, after which, I received, in private, a lecture from my mother on my unladylike behaviour in giving too enthusiastic demonstration of affection in public.

Page 18

On returning to Napier, Pop found that lots of helpers had moved in to the town and to start with had helped themselves to all his tools and most of our other meagre belongings. Without more ado Pop became a burglar and by the time we returned, he had a few well selected items to start us off with again. He never committed a mean theft and assured Mother that he took only from the “bloated capitalists”, whoever they were.

There was one awkward moment when a neighbour exclaimed over the carnet [carpet] runner in the hall. “Mrs Murray had a carpet just like that, but it was a much lighter colouring and it was stolen after the ‘quake.” Mum said she had seen it in a lighter colour, which I knew was the truth, because I had helped her to apply the Fairy dye, – but with young children the darker shade was more serviceable. I think the dinner set with which Pop replaced the broken tea set was an even nicer design. Though it did not have the sentimental value of the latter. I still have a meat dish from the dinner set and for me it has acquired that value over the years.

The chimney was not repaired for a while, as the “brickies’ had rather an accumulation of work, so we had barbecue cooking, though we had never heard it called that then. It was often a case of “first steal your food” and as the looters had kindly left some of Dad’s colours, which he used in French polishing, one of his favourite characters for these excursions, was that of a Chinaman. An application of yellow ochre powder, a moustache of hairs from the broom and the ‘Yellow Terror’ would strike again.

We kids were terrified of Pop getting caught. In my case, it wasn’t because he would have to go to gaol and maybe perform hard labour, breaking rocks on Bluff Hill, but because I knew the girls at school would turn their noses up at me if they heard about it.

Once, I was an unwilling accomplice. Pop said “There’s a table cloth or something fallen from a balcony where it was airing, into the bushes below. It’s been there for a couple of days. I think we’ll take a walk tonight Bett.” We were right out of tablecloths at the time and newspapers didn’t look the same somehow. Mum begged for me to be left at home, but I was I good size, thanks to malnutrition, for getting under the bushes, so away we

Page 19

went. Pop wore dark glasses, sandshoes and carried a walking stick. I wore my school clothes and I was quite sure that if things went wrong, I would be abandoned at the scene of the crime without any compunction whatsoever. My father gallantly hoisted me up on to the bank where the house was and I crept up to the bushes, grabbed the white object and returned smartly to dear old Pater, who escorted me home with our trophy.

Mother, already overwrought at my apprenticeship, nearly wept when we examined the takings. “Why, it’s a baby’s satin pram cover,” she said. “It’s no use to us and such a pretty thing. The mother will be so upset.” I refused point blank to return it, so Mother dyed it dark green, folded it double and we had a green satin cushion for twenty five years. After that Pop worked alone and usually concentrated on outside food safes. Once he broke into a butcher shop in Hastings Street, but was nearly caught, which damped his ardour somewhat and after that he tried to keep to the great outdoors.

Of course, there was the odd windfall, if one knew how to seize opportunity with both hands. One day, when we lived in Shakespeare Road, a duck flew off the back of a truck and over our hedge. In all the town, she could not have chosen a worse Sanctuary. Pop heard a “Quacking which was the duck’s last utterance. The truck roamed back and forth along the street while the driver searched for his lost passenger and on the road overlooking our backyard, a detective sergeant, who lived above us, in more ways than one, stood smoking his pipe and surveying his back garden, while Pop, with a bucket of hot water, sat in the washhouse handling the situation “pluckily”.

Mother went to the mart one day and came home greatly excited. She had bought a sewing machine to replace the one smashed in the earthquake. It had cost four shillings and after bidding for it, without a penny in her purse, she asked the Auctioneer, who knew her from happier days, to trust her till the end of the week to pay for it.

One of the first things she made was a little overcoat and cap for Ron. Mother taught him to doff his cap to the few remaining ladies we knew and they were all charmed with the little gentleman. This training in the art of gentle living continued till Ron started school,

Page 20

when within a week, he came home with this first “blood nose” administered by a classmate because poor Ron, true to his training, rose and opened the door for a lady teacher as she was about to leave the room.

And so we came to Coote Road, to a little old wooden shack up a right of way and along past the backs of other houses. It was the sort of place that people these days strive to preserve for posterity to see how the early pioneers lived. Kitty and I liked it because our bedroom had a ceiling, which sloped down to within about four feet of the floor.

We were nearer to starving in Coote Road than anywhere else and I have vivid memories of a Christmas repast of bacon rinds and barley boiled together. A deal old lady lived next door and she felt so sorry for us that she started cooking huge rice puddings, which she would hand over the fence to us and we tucked in happily till Mother’s pride got the better of her and she declined to accept any more offerings, which must have hurt the old lady even more than it did us.

Our dresses at this time were made solely from remnants or old clothes of Mother’s, but it was really amazing what she could produce from two or three pieces of different patterns and she turned out some real masterpieces, with front panels or sleeves of different designs and colours, but always toning beautifully. Perhaps that is why I cannot today take to the present fashions incorporating more than one colour or material they bring the smell of poverty too close.

In one of the houses down the right of way, there was a family with about six little ragged kids playing in a. stonewalled yard which never saw the sun. Mother took a fancy to the youngest little urchin, always giving her a gracious nod and smile as she passed. There was a, remnant of orange checked material that was too small to utilise for any of us, so

Page 21

Mother set to and turned out a cute little frock, which she parcelled up neatly and dropped over the wall to the child. We were uncertain how the parents of the child would receive this offering, but a few days later she was wearing it and we were delighted that the offering was accepted.

On Sunday mornings the family would go for a stroll, with the three children carrying small bags into which we put puha, picked from the roadside when nobody was looking and then home we would go to cook it for Sunday dinner. It made a nice change from bread and dripping. Sometimes we had meat, but sometimes too, the butcher would turn us away sadly saying, “Tell your mother I can’t let you have any more meat till her account has been paid.” The shame we felt on these occasions was crushing and we always waited till there was nobody else being served before we dared to enter the shop, as an audience was the last thing we wanted on these miserable moments.

We stole our electric power and Pop even found a way to get the shillings back from the gas meter once they were in. Perhaps he should have patented that. Of course, both the gas and light meters were changed after a while because, as the meter readers said “they weren’t registering correctly” and we had to watch our step after that. Dad got some French polishing jobs to do at home, but it was mid-winter and for good results the temperature must be just right. One day, he put in the card to hold the meter from going round (some people used a, needle, but we deemed that a dangerous practice), placed a 200 watt lamp, which he had “come by” in the light socket and with an old bar heater going as well, raised the room to polishing heat, whilst the rest of us froze in the kitchen. Suddenly, Mother saw the meter reader puffing up the track to the front door, which was cheating on his part, because the meter was at the back and he wasn’t supposed to come on a Saturday afternoon anyway. There was just time to whip the card out, turn off the heater and hide it in a cupboard, before the knock came on the front door and the reader was admitted. To get to the meter he had to pass the room where Pop was working and

Page 22

the blast of warm air stopped him in his tracks. He looked very puzzled but I think he was on our side, because though he made some comment on the 200 watt bulb, which had been left burning to account for the heat, being rather strong for a small room, there were no repercussions from his visits apart from the account, which we probably didn’t pay anyway.

We were unable to pay the nine shillings a, week rent and the landlord, Mr. Luke, was understandably, becoming rather impatient with us, so we looked around and finally found a very nice house back in Wellesley Road at 25/- per week!! We couldn’t pay nine shillings, but were willing to owe 25/-. The parents must have been feeling optimistic about this time – perhaps Pop had a job lined up – for they paid 10/- deposit and when next Mr. Lake [Luke] called Mother informed him that we would be leaving that weekend. When he enquired as to our future address, Dear Old Innocence told him, and later that day our future landlord’s son, who, to add to my shame, was in my class at school, returned the deposit with a brief note, which put the lid on that move.

Pop was justly incensed upon his return home, to learn that our plans had gone awry, and after calling Mother all sorts of Pommie and Woodbine (she called him a crude colonial in return) he turned his rhetoric powers to the unfortunate Mr. Luke and we had long speeches on, “Man’s inhumanity to man” and “bloated capitalists”. Goaded by Mr. Lukels [Luke’s] inhuman treatment, we found our first house on the Marine Parade, up near the Prison Reserve and as Pop was a great one for poetic justice, we did a moonlight flit from Coote Road and Mr. Luke still hasn’t got his rent. Whenever this gentleman came face to face with Pop in the street, Mr. Luke would look away and Dad would call out brightly, “Good day Mr. Luke. Lovely day!”

Years later, when we had climbed quite a distance up the social ladder once more, Mother and I were at a garden party where the grounds overlooked Coote Road. We wandered with a girl friend of mine to the hedge, to survey the scene below. “What a,

Page 23

funny little house that is back there,” said Coral. “Whoever would live in a place like that”.

“Who indeed?” replied Mother gravely and I said, “Just like a doll’s house, isn’t it?”

“More like a dog’s kennel,” replied Carol, almost forfeiting my friendship on the spot.

After a short stay on the Parade, we moved to Miller Street and thence to Thackeray Street, to a house where the previous occupants had tried to run a tearoom. They had a placard on the front porch which read, “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you may get work”. Dad was on relief work it this time, with stand down week every third week, which meant that just as the family was recovering a little, it was time to have a week without work or pay and that put us two steps back from the step forward we had taken. The middle week was always shadowed by the words, “Stand down week next week – We’ll have to be carefully [careful] – as if we were ever anything else by this time. Pop tried to earn some honest money by putting all the old vases and books he could find in the front room window, with prices like 3d and 6d on them but trade was not brisk. One day, he took the portable writing desk given to him on his wedding day, by his father-in-law, and sold it in a shop in “Tin Town”, which was the business centre of Napier after the ‘quake, before the shops were rebuilt. He received 4/6 for the desk and after he had pocketed this, the shop keeper, who had seen a similar desk before, showed Pop where the secret drawer was – and there was a gold sovereign therein – which the shopkeeper pocketed. This upset my father so much that he got beautifully drunk, with the 4/6 and that was that.

Page 24

There came a, strike by relief workers and Pop wrote a poem to mark the occasion, which began, “There came a call from Station Street, A call from Mr. Kay, that the relief workers were on strike in the province of Hawkes bay.” I thought, it was a wonderful effort, but it didn’t feed us – in fact achieved nothing at all.

Ron had a birthday and Dad, in a burst of energy, made him a wooden horse on wheels, which Ron proudly dragged round the streets. It had its name; “Phar Phrom It” painted on the side, as at that time the great horse “Phar Lapp [Lap]” was hitting the headlines. Whimsical man, my father.

I was coming home from school one night, when I met a girl from next door to our place. She said, “You have to hurry home at once. Your Auntie Kate is coming on the 5 0’clock [o’clock] train tonight.” This was rather surprising, as Auntie Kate lived in London with the rest of Mother’s family and she had neglected to write and tell them of our varied changes of address and that life in the colonies was not quite up to her expectations. How Kate traced us, I know not, but we were all polished, admonished and taken to the station where sure enough Auntie Kate stepped from the train in her elegant London clothes, to greet her threadbare relatives. She was escorted, on foot, to our place of residence, with Pop struggling manfully with her cases.

It was a bitter sweet time for Mother. Auntie Kate purchased miles of sensible navy blue wool and we were speedily decked out in new jumpers and matching berets. The words of the popular song of the day, “You are my heart’s delight”, were written on a scrap of paper and attached to the wall over the stove, so that the house was filled with this song, and many others, for the length of Kate’s stay. We were immensely proud of her. She had served as a nurse in France in the First World War and had been matron of Royal Sussex Infirmary for many years. She had been places and seen things and had many gripping stories to tell, which rivalled even Pop’s masterpieces.

Page 25

Auntie Kate’s husband had died shortly before the news of the Napier earthquake was received, so she took off round the world to find for herself how we had fared, as Mother had not sent any word of our fate. She stayed for a month, sharing the double bed with Mother, where it seemed to me they spent most of the night whispering to each other, and boosted the morale all round, once the shame of having been found by her in such a situation was overcome. Pop was relegated to the back bedroom and of course he didn’t risk any burglaries while we had an honoured guest under our roof. When I visited Kate in England twenty years later, she said “We all had a good cry over you when I returned to England with news of your circumstances.”

Page 26

We lived under the shadow of constant hunger, fear and cold and though thousands of people were in the same desperate straits, we felt that we were different and therefore outcasts.

One teacher at Central School dealt me a blow I have never forgotten. I had pains in my knees one winter and could not do my P.T. very well. One day the teacher called out to me, “Betty, YOU are the ugly duckling of this class. You are far too stiff in your movements.” I found enough courage to say, “My mother thinks I have rheumatism in my knees.” “Well, what do you expect when you come to school in midwinter in just sandshoes and no stockings.” This information I duly conveyed to Mother, who racked her brains and the rag bag. The only answer she came up with was a pair of old silk stockings, which she spent half the night darning, though it was a major reconstruction job. Thereafter my legs were warmer and my shame complete. Perhaps the sight of this scarecrow in silk stockings and sandshoes informed the teacher concerned that I was not lightly clad from choice. She never married and developed into a tightly corseted bitter old woman, who walked like an aged bulldog. I can’t say that the Ugly Duckling turned into a swan though!

On Saturday mornings we were able to buy food very cheaply at a social service depot nearby and there was always a fight when it was time to do this errand, as nobody wanted to been seen receiving this charity. However the job fell alternately to Kitty and I and if we encountered any of our schoolmates there on a similar errand, we would try not to be spotted or else exchange a subdued “Hello” and inspect the floor intently till we were served and could make our escape.

At our most desperate moments, even Mother had to bend to a little dishonesty and she gradually unloaded all her foreign coins through her innocent children. She never told us till we returned from the errand that the sixpence we just spent on food was actually ant [an]

Page 28

Over the years, Mother learned to turn her hand to many trades, one of her most successful talents being that of shoe repairer. Pop tried it once, but Mother found that the reason for Kitty’s limp was a layer of leather applied by Pop with more enthusiasm than skill on top of the curled edges of a gaping hole in the sole of her shoe. She became without more ado the family “snob”. We would be sent for 2/6d worth of green leather (must be green) and Mother would get to work, removing the old sole and applying the new with ever-increasing dexterity. Of course, it was often necessary to effect the repair with a piece of cardboard on the inside of the shoe, until the price of a piece of leather became available.

Pop earned 4/- for each radio cabinet he re-polished for one of the local music stores and this little extra was well worth having. Mother and I became expert polishers all of a sudden. It happened that the man from the shop had called twice for a cabinet, which Mother informed him was not quite finished, as Mr. Stowell was out on a job. The work wasn’t even started. Pop was a job and he was “out”. We tried in vain to rouse him and then got to work with dark mahogany shoe polish and lots of elbow grease. The man collected the cabinet, we collected and spent the 4/- and came near to collecting a thick ear when Pop came to. However, we then learnt to polish properly so that we could help out if ever the pressure of business became too great again.

Of course sewing paid for many necessities and Mother treadled Kitty and I through high school with her machine. People did take advantage of our situation and the pay for various garments varied greatly according to the means or nature of the client. It was a mechanised “song of the shirt”, though Mother’s voice was never of dolorous pitch thank goodness.

Page 29

We loved the Marine Parade and were very lucky to have lived in three different houses there. The beach was our playground and the sea from time to time, provided unexpected bounty. When Ron was a little chap, he played all day on the beach and I think loved it more than any of us. He had to come home and report to Mum every hour, by the T. & G. Clock and if he was required at home before then, Mum would open the front door a crack to make sure there was nobody to view her unladylike behaviour and when all was clear she would open the door wide and give voice to a most amazingly powerful yodel, which set the seagulls on their ears and never failed to bring Ron at the run. The door was then quickly and quietly closed and startled pedestrians resumed their promenades convinced that it must have been the mating call of a [a] gull.

Ron kept us supplied with drift wood for the fires and at various time returned in triumph with other trophies, such as a 22lb snapper, which he was too small at the time to lift, but being reinforced with big sister and a big old basket, managed to bring home his splendid catch. We decided it hadn’t been dead very long and it was delicious. After particularly rough seas there were lots of crayfish, obviously torn from their hiding place washed up on the shore all alive ho. We had several old cane baskets of large size and would walk along the shore picking up the live crayfish and I still remember Mum’s spirited reaction when she came in one day to find fifteen live crays crawling over the kitchen table.

Another day, six black swans flew over from Bay View and settled just past the breaker line so Pop settled on the beach and was rewarded beyond his wistful dreams when an extra big wave bowled three of the birds and they were caught in a flurry of foam. Pop was there and a quick twist of the wrist ensured a lovely dinner. A little boy, about five years of age, who had also known an empty belly, ran down and followed suit, but Pop kindly helped him with the neck wringing and it must have been a wonderful sight to that child’s parents to see their boy stagger home with a swan as big as himself. The

Page 31

Once the tidemark was beautifully outlined in tiny silver herrings and the old wicker baskets were pressed into service. Another time Ron really amazed us when he came home with a rainbow trout, but even the hungry Stowell family couldn’t stomach that one and it was returned to the foreshore to the audible relief of the seagulls.

One bleak Sunday afternoon Kitty, who was becoming a very comely young lady, was humping her basket of driftwood over the old sea wall, when the manager of the local tobacco came by and was touched at the sight of this poor child gathering wood for the fires. He inspected her load and said, “That is too wet for firewood. Buy some coal my child.” He handed her half a crown and she went and bought a lovely big box of chocolates, which we ate as we sat round the driftwood fire.

After a stormy sea, we would be down on the beach, gathering wood, admiring seaweed and from time to time bringing home wonders of the deep. Once Ron and I found a cute little puppy still alive among the debris on the beach, but when we took it home it could only move round in round on its belly and Pop had the job of knocking it on the head and disposing of it. I treasured a dead sea-horse for a long time and Ron had similar favourites.

Ron soon learnt that beer bottles were and excellent source of revenue and he would mark the site of any drinking parties and return later for the bottle’s [bottles].

Every evening after tea Ron would say, “Are we going for our nights walk Bett?” and off we would go along the seafront to inspect the ever-changing scene. Sometimes the way the little breakers curled over would remind us of a loin of mutton while at other times, there would be a hiss and a roar and a swirl as the flat waves lashed up the beach towards us. We would find flat stones among the shingle to skim, or sometimes we would throw one piece of pumice in the air and try to hit it with another shot before it came down.

Page 32

After the earthquake, the rubble from the ruined shops was taken down to the beach and gradually the new promenade was formed on top of it. At first, it was quite a long run down to the beach, from the top of the curving wall, but over the years the shingle piled up till it was possible to step from promenade to shingle without much effort at all.

In November every year Ron started his bonfire collection of old tyres, driftwood, dried seaweed and anything else that came to hand. This he would build on the beach and add to until the great day came. We would restrain him till it was dark enough for the fire to be lit, in company with all the others which had been built by industrious children, and we would hoist the poor old guy to the top of the pyre and dance with glee as the flames soared round him.

Ron’s store of beer bottles would have been transformed into fireworks, which he shared generously with Kitty and I who preferred the pretty ones to the loud bangers which were Rons speciality. A launch or two would sometimes cruise close on shore if the sea were calm enough and this added to the general air of festivity.

Of course we swam in our ocean most days in the summer and became used to its changing moods and fancies. We would feel gingerly with one foot to find out where the “dip” started and report to each other on its depth as this varied considerably from day to day.

We learnt to respect the rolling billows, which flowed in unceasingly with a dull roar, as an error in judgement could result in the swimmer being rolled round and round and then soundly dumped, which could be both painful and embarrassing, unless it happened to one of the others, when it became an uproariously funny incident.

There were days when the waves did not appear very big, but suddenly three whoppers would appear in quick succession and if we were drawn out by the undertow of the first, we learnt to wait for number three to ride back in on. The undertow on these occasions

Page 33

was terrific and Ron was made to play on the edge until he was big and strong enough to hold his own with the waves.

One day, when Ron was about six years old, he and a friend named Eric were playing on the edge with an old wooden box as it was too rough for them to venture out with the rest of us. After three big waves came the cry, “Eric’s caught!” and there was Ron jumping up and down on his own and I had a glimpse of Eric being swept past at a great rate and out under the waves. His head bobbed up close to me and as I grabbed him in a manner not recommended in our life saving lessons, I wondered at the size of his great black eyes as they opened briefly. The sea had done its worst and was now sulkily jogging up and down, but I was able to push Eric in front of me to where Kitty and Pop could take him. He recovered quickly enough and I doubt if his parents ever heard what had happened. I lived in a virtuous glow and smirked happily when Pop called me “Life saver Bett” at tea that night. I thought my great deed would go down in history, but just a few weeks later I overheard Mother relating the tale to a friend and as I paused to gloat once more over the tale, I heard, and if Kitty hadn’t been there to catch him as he came up, we would have lost him, I’m sure.” Farewell fame! They couldn’t even get the heroine’s name right.

We saw a real rescue one very rough day, when two men went in swimming near the baths. One was local and the other was from Australia and assured everyone who tried to dissuade him that he knew how to handle a “bit of surf like this.” The local lad came ashore very quickly, but then he walked up and down the beach calling to his friend, “Fight! Fight!”

It was obvious that the swimmer was in difficulty and when he put his hand up as he went under a couple of times, Kitty, Mother and I were nearly beside ourselves and asked each other “Why doesn’t someone help him?” Soon the lifebelt was brought out and it was the swimmer’s friend who donned the belt and went to the rescue. After a terrible

Page 34

struggle, both men were brought to shore, the rescuer collapsing in the foam at the water’s edge, while the rescued strode manfully up the beach. The exhausted man was revived with brandy, but when the Australian asked for a sip also he received a very cutting reply instead.

We swam in the baths, the cheapest way of getting in, being to get wet in the sea first and then run in with dripping costumes along with the legitimate customers, who would often leave the baths for a dip in the sea and then return without further charge.

Sometimes the sea would be warm mild and friendly and even the dip would iron out in to rippling sand instead of the hard scoured pebbles we knew so well. The water would be blue instead of greeny grey and we would float happily on our backs though still keeping an eye open for a big wave from nowhere. How we loved those calm days after the zestful roaring stormy ones, but if the sea were calm too long we would then wish for something to fight and struggle with once more.

Yachts, launches, fishing boats would come close to shore sometimes and once I gazed spellbound at a canoe being propelled with flailing paddles on the crest of a wave, heading for the shore. The interesting thing was that the canoe beat the wave. Wow! I had a glimpse of sky between wave and craft before all was lost in a flurry of foam on the hard shore. Luckily the canoe appeared more sheepish than hurt, though he ventured no more to sea that day.

Mother always walked down to the sea and got wet quietly without any fuss or bother, Ron and I usually dived in, while Kitty waded out and then ducked under. Pop usually brought up the rear a few minutes later and would stroll down to the sea, stooping every now and then to rub sea water over his arms and legs and winding up with a sort of flat twisted belly flopper into the waves. Then he would strike out manfully for a few minutes and return up the beach to lie in the sun, while Mother exhorted us, “Don’t go too

Page 35

far out. You’re far too venturesome.” Mother at one time decided that a mouthful of seawater a day all round would be beneficial, so for a while it was, Ron, have you had your mouthful yet?” “Come along Bett. It will do you good.” We were glad when she forgot about it.

Ron and I knew the Parade and beach from the Gun Club at Awatoto to the breakwater and wharves at the Port, though most of our walks were towards the reef and breakwater. We would pass Dr. Moore’s Hospital, leaning over backwards after the ‘quake, the baths, swings, paddling pools and head down towards the reef, which always seemed to hold great interest for us. We were allowed sometimes to go fishing at the wharf, though if Mother had seen us walking round underneath on planks, she would have put the place out of bounds on the spot. We never brought home any worth while catch, but there was always hope and a feeling of great adventure, as we knocked at barnacles on the piles down below or even ventured far out on the breakwater and clambered over the huge square slabs of concrete as close as we could get to the waves.

Other times we would lie quietly on our bellies on the sunbaked wharf and watch the tiny fishes darting at our lines in the dark green water. How is it that the sun doesn’t have that sort of warmth to wrap round one any more? We never felt a breeze or felt a chill as a cloud crept over the sun. It was just one long sunbaked delight. Ho. Hum.

In Ron’s early days toys were conspicuous by their absence, but ingenuity made a lovely swing for him – an old tyre hung from a tree. Mum invented a game called motor cycle races” three marbles placed in the bottom of the colander and the vessel slowly rotated while the marbles raced round the side like “the human daredevils”, coming right up to the rim and down again. What a racket they made! We had some tennis balls left from when Mum played tennis with the other ladies in the old days and Ron and I played skittles with dolly pegs for targets.

Page 36

We had illnesses of course, but the doctor was out of the question till all else had failed.

Mum had several terrible bouts of toothache and would walk round the house with swollen face, trying, to relieve the pain with a clove or a drop of eucalyptus on the offending molars. It was many years before she was able to have dental treatment. Ron had congestion of the lungs and was sent to a Health Camp for convalescence, but he was as pale as a ghost for months after. I became very ill, but was old enough to know that a visit from the doctor would cost 10/6, so insisted that I was feeling better, while my doubting mother sat by my bed, knowing that I was a little liar. When the pain in my chest finally won I was rushed off to hospital with pneumonia, which took quite a while to clear up, but the food in there was plentiful and I rather enjoyed the experience, once the worst was over.

Things gradually improved. Pop had more regular work, such as polishing the woodwork in new buildings rising from the ashes of the ‘quake and Kitty started work at the magnificent sum of 12/6 a week. Of this, she gave Mother 10/- and was passing rich on 2/6 a week for clothes and other luxuries. Mother sewed frocks for her more affluent friends, generally receiving 2/6 per frock.

The sheets we had known for years, with the faded red inscriptions, “Use no hooks” and “Champion”, were gradually replaced with real ones that were not joined all over like patchwork. The first lot of sheets and blankets were put to excellent use as we could then take in a boarder, though sometimes the shoe was on the other foot as the boarder would be even worse off than we were.

Young Farrow, our first lodger paid, (or owed) 2/6 a week for our best front room. He was a sewing machine salesman and not remotely successful in this role, though quite a decent young man. He was often hungry and sometimes, when his “belly thought his

Page 37

throat was cut”, according to Pop, he would stand talking to us in our kitchen doorway, while we ate out [our] dinner, his eyes following the forks on their journeys and I would feel so bad about this that I would try to time my intake for the moment when he was watching Pop or one of the others.

As we all felt like this to some extent, there would be long pauses in consumption and if we had any bits left over, Mother would weaken and say, “Would you care for a meal?” Mr. Farrow?” and the poor drooling wretch would either make a feeble attempt to drag himself away, or, if the pangs were too great, accept with shameful alacrity. He left owing us quite a bit of rent, but we know it was not his fault and bore him no rancour – in fact we worried about him for some time, as we suspected that he was living in a little storeroom with his sewing machines for company.

We next had a nice quiet girl, a hairdresser, I think. She was so quiet and slow that we naturally called her “Fireworks” among ourselves. The lodgers came and went and as most of the later ones paid their rent, we bought more beds and sheets – and took lodgers – but never more than three at a time. Gradually we had a real home again and life chugged gaily on, with the ever beloved sea, at our front door. We were never allowed to think of our place as a boarding house and the residents were to be called at all times lodgers, never boarders. Casuals coming to the door looking for rooms were all turned away with the words, “No, this is a private house”.

There was great excitement when Mother managed the purchase of an ancient piano, complete with borer, but with quite a pleasant tone, rather like a spinet. Kitty began to take lessons and was soon able to play hymns for her class at Sunday school. My mother played by ear and often we would find her sitting in the light of a softly shaded lamp reviewing old favourites like “Moonlight and Roses” or “Sweet and Low”.

Page 38

I went to work, Ron to High School and Pop, when the war started, promptly joined up again, even though he had been discharged as permanently unfit after the First World War. He was too old to go overseas, but threw himself into Army life with enthusiasm. Usually he was able to live at home, so it was just like an ordinary job.

Kitty’s fiancée went overseas and I abandoned the role of leader of Ron’s gang to become her companion. We joined the Services Club, where we helped to entertain visiting servicemen and boys from our own town who were on leave and helped out with the Sunday evening services

Becoming belatedly culture conscious, I decided to take piano, singing, and ballet lessons and joined the Church choir and one of the local drama clubs – no half measures for me!

We were never allowed to go to parties where there was drink, but we seemed to fill in our time quite happily in spite of this ruling.

Kitty kept an eye on my romances at the Club, which was just as well, as I occasionally did get my lines tangled, in all innocence of course. Once I met an English sailor from a ship in port and at the end of the week, I agreed to go to the pictures with him, as he was due to sail on the morrow. We had a pleasant and uneventful evening and as he said farewell at the gate, he announced that he had fallen in love with me. If the ship kept to its present run he would be back the following July, so would I wait for him? I thought, well, I’m not likely to be anywhere else by then,” so I said, “Yes I’ll be here”. I received a couple of very flattering letters from him to which I replied in light hearted vein and then heard nothing more for three years. One evening came a knock at the door and there he was. The ship was in Wellington, so held got leave and rushed up to see if I would marry him right away. The engagement ring I was wearing helped to dissuade him and he went sadly on his way saying, “My Mum kept telling me I should write to you more often”.

Page 39

One day, when I was working in a music shop, another young Englishman entered the shop and my life. He was suffering from a bad cold and it took quite a bit of agonised whispering on his part before I deducted that he was interested in purchasing a recording of the “Nutcracker Suite”. I was delivering my usual line about the difficult we were having in obtaining records from overseas, when my eye fell upon the small Merchant Navy badge on his lapel, so I didn’t waste any more breath on the subject. The sailor then asked me, as so many did, what dances were on in town, so I directed him to the Services Club. “Will you come and dance with me?” he asked. “No, I’m afraid I can’t be there tonight.” I replied and then weakened saying, “Perhaps I will be there tomorrow night.” I went home to Mother who always heard all about my romances and said, “I met an English sailor today. He wants to see me at the Club dance tomorrow night, but I’m not too sure about whether I like him or not.”

“You’d better take Kitty with you then, if you do go,” said Mother. Came the evening in question and it was nine o’clock before I decided perhaps I would go after all, so my long suffering sister was obliged to accompany me. We met Bill, the sailor, in the doorway. “I’d given up hope,” he said. “I was just leaving.” He changed his mind and we had a wonderful time which Kitty also was able to enjoy, as Bill had a friend with him, who was engaged to a girl in England and they danced and, exchanged notes about their fiancées, while Bill and I just danced till the music finished.

Two days later, the ship sailed and we settled down to a steady correspondence and I regarded it as absolutely miraculous that whatever subject I chose to write upon, Bill’s letter from some outlandish place of the same date, would so often contain very similar sentiments. He was an Engineer on the “Glenartney” which had just come from Singapore.

Page 40

The cargo, I learned many years later, consisted of Spitfires, ordered by the Dutch Government and delivered to Batavia, where the ‘planes were machine gunned by the Japs and burned on the roadside soon after unloading. On board was also a gun barrel to be delivered to the “Prince of Wales” at Singapore. The “Prince of Wales” was sunk as the Glenartney was approaching harbour, so they had a spare gun barrel to carry round.

After returning to England, Bill went to the States as part of a crew to take delivery of a Sam-boat, and he sailed from Baltimore to Calcutta with a vital cargo of “old Gold” and “Pepsi Cola” and then back to England. He was always hopeful that the next trip would be the one to bring him back to our part of the world.

We had agreed that as we had known each other only three days, it would be as well to go out with other friends as we wished. I had two or three local boys who took me out from time to time, but they all knew about Bill and that I was determined to have another look at him before settling down. We also took home boys from the Club, when we found how Mum loved to hear first hand of the old country, though she had long given up any hope of seeing it again. We found a boy from Forest Gate, London, where our mother had grown up and Kitty and I might just as well not have been there, for all the attention we got. If any of the boys had a favourite dish, he would be invited to dinner and that dish would be on the menu.

Mum really loved these little dinner parties of hers and so did the boys, because long after Kitty married her returned fiancée and I, having stuck my neck out as usual, had been manpowered to the munitions factory at Wellington these lads would call on Mum, with bouquets of flowers and have dinner there as often as they were invited.

After Bill had tried for two years to return to New Zealand, he missed several of my letters in a row, and became a little concerned. This caused him to cable me from Bombay, “Missing mail. Will you wait”. I had already decided not to do anything rash before he returned, so sent the economically worded reply “I will wait”. I was amazed a

Page 41

week later to receive a cheque and cable, saying “Wish I could help you choose your engagement ring”. I said, “Mum, I must have got engaged! Surprise, surprise! The engagement ring was chosen the local boys retreated and hope fluctuated for two more years before Bill managed, the war having at last finished, to find a supernumerary passage on “The Nestor” or as far as Sydney and then on to Auckland by flying boat. My girl friends were all agog to meet Bett’s mystery man and I was offered wedding frocks to borrow and several friends were busy deciding for me just where we would have the reception and how many guests there would be!

I was concerned with why all this was going to cost my parents, who still had no little nest egg put by and also the nagging thought, “What if I don’t like him?” and worse still “What if he doesn’t like me?” In this frame of mind, I met the flying boat in Auckland – and we seemed to like each other all right, but Bill was naturally nervous at the thought of a wedding among so many strangers. We started the journey by train to Napier, but stopped off at Putaruru and arrived on Kitty’s doorstep with the words, “Do you mind if we get married from here on Friday?” As this was Monday, she was a little taken aback, but rose to the occasion magnificently and we got in touch with Mum by ‘phone to break the news. She was probably secretly relieved at the solution to the problem and popped the wedding cake into the oven without more ado. Pop was for some reason unable to get leave from the Army at the time, but sent me a token in the form of a good pair of brown kid gloves, very closely resembling those issued to WACC’s, from the Quartermaster’s stores.

Mum and the cake arrived and the minister and lady organist from Kitty’s church entered into the romantic spirit of the occasion with great enthusiasm. It was a pleasant ceremony and we had the Wedding march” and “Where ‘ere you Walk”, into the bargain.

After the honeymoon, we returned to pacify all the friends who had so dearly wanted to organise the proceedings and they were all very decent about it and wished us well.

Page 42

None of us were much good at helping in the house I’m afraid and Pop least of all. Mum would be tearing round like a scolded [scalded] cat serving the meal and Pop, who would have got on very well with Andy Capp, would say, “Bring the sugar while you’re resting”. Or, occasionally conscience would spur him a little and he would say, “Any more tea in the pot?” then “I’ll get it” but never moving a muscle so to do. A nice thought though. Every day for decades, Mum would get up at seven, make a pot of tea and then climb the stairs with Pop’s cup first and then make a second trip with tea for Kitty, Ron and I and we took it for granted.

Even after we were married and returned home for visits the routine was the same, though by this time we had developed enough decency to try to beat her to it, but the home beds were so soft and comfortable that we never did wake till the telltale creak would sound on the stairs.

Came a time when Mum finally went to the doctor and it was found not surprisingly, that her heart was in a very shaky condition and she was advised to take things quietly and not rush anywhere. Pop was quite concerned over this – to the extent that he rigged up a plastic basket which he tied to the top of the banisters upstairs and when Mum had made his tea in the mornings, she no longer had to climb the stairs with it. A gentle yodel from her in the hall sufficed and Pop would climb slowly out of bed, lower the basket, into which Mum would place the cup of tea and Pop would haul in his catch. He was a clever man, was Pop! The only time I tried it the cup tipped over, but those two had it down to a fine art and never a drop did they spill.

The idea of taking things quietly was not well received by mother and she digested the Doctor’s words as she walked briskly home, indulging in her usual practice of nipping across the road between the traffic – still a Londoner at heart, however weak that organ might be now.

Page 43

By the time she reached home she had decided against a quiet life and the thought that she would never be permitted to run or dash up the stairs again irritated her so much that she went straight out to the back yard, raised her skirts a respectable distance above her knees, and ran like the wind up and down the yard. Nothing happened, so she decided to forget the whole business and enjoy herself, which she did. The last movie I have of her is at the age of 72, a month before she died, swinging Indian Clubs in the back yard! My son had found them – tucked away under the stairs and asked what they were result – a very lively demonstration.

The auction marts were a never ending source of pleasure to my mother and I and whenever I visited Napier, weld include these places in the itinerary. Pop would get most annoyed if any money were spent on old junk, so we often had to smuggle things into the house and it wasn’t always easy to conceal our purchases. I remember going home one weekend and Mum whispering that she had a lovely full length mirror for me, if we could only get it out of the wood surrounding it, thus making it possible to fit it in the car. My husband, poor man, was asked to challenge his father-in-law to a game of snooker at the Club and make it last as long as possible. They departed and Mum led me into her be room, where the mirror was concealed behind a chest of drawers. It was a huge oval affair and I think had been the backing of an elaborate display in a confectioner’s shop – a type of overgrown sideboard. It was a terrible job trying to get the wood off the glass and I got to work with a carpenter’s saw, in the middle of the bedroom, so that there would be no telltale sawdust elsewhere.

It was slow work so Mum produced another saw and there we were, both going for the lick of our lives, giggling like mad, scared the men would return before the deed was done, scared the glass would break and I had the additional thought that Mum could drop dead at any minute and everyone would blame me! However, we did it!

Page 44

The joy Mum got from this piece of carefully planned and executed deception probably did her heart more good than all the pills she had lined up by her bedside.

By now, Mother had made a very nice home, well polished and with objects d’art chosen with great discernment from the marts over the years, it was a really elegant establishment. I don’t know at what stage my parents decided not only upon separate beds, or rooms, but floors, but with the big house to themselves, Pop slept upstairs and Mother downstairs. It seemed that as they became older, they slept less at night and with this arrangement, either one could turn the light on to read whenever they felt so inclined. Mother also liked to get up and drift round the house in the moonlight and when we were home at holiday times, I would see the pale ghost float by, her hair hanging in braids down her back Nobody else saw her as she was so silent in her movements and once I became used to her nocturnal perambulations, I felt a quiet enjoyment in her presence .

Pop left the army at retiring age and spent his last fifteen years doing odd jobs as the mood took him, sitting in the sun watching the sea, or occasionally acting as unofficial custodian of the Parade if he saw anyone throwing litter on the beach or otherwise offending his sense of what was right and proper. His methods of meting out justice were often unorthodox but always apt and efficient.

At this stage he decided he needed some form of locomotion, so he bought an old Indian motor cycle and jogged happily around on that ever after. One of his first trips was over the hills from Napier to Taupo. Something happened to the clutch half way there, but an old bent nail effected an adequate repair and the trip was completed without further incident. Then he fell off in the main street of Taupo and bruised his hip.

Pop was now able to go out to the rivers near Clive to catch whitebait and many a hearty row he had with the other crusty old codgers who took his favourite place. I think it gave from [them] all something to live for.

[Page 45 blank]

Page 46

Then came the final big trip and Pop set off on the trusty and rusty machine to revisit the scenes of his childhood down Levin way. He told me he went to the district where he was born and slept the night under a hedge on the farm he knew as a child. He appeared deeply satisfied with the trip, but did not give us any detailed report.

The residence was in close proximity to one of the hotels and when in later years a beer garden was built, it provided joy anger and entertainment for us all.

Whenever we visited home, we knew that on Saturday evening at six sharp we had to be all in our chairs in the upstairs front room where Mother could “Tut tut” and Pop and the rest of us enjoy to the full the spectacle of closing time. Saturday was of course the best night, but other nights could be fun too.

Mother and Pop of course had names for many of the regulars and I often think kindly of “Flagon”, “Scavenger”, “Malt” and “Oughterbee”. The latter was so named because he one evening negotiated his way as far as our front gate, where he stood and surveying with distaste the world around him, pronounced to the strained ears above, “A feller oughterbee bloody well dead.”

Mother had a great affection for the police dog “Luger” and was always pleased when this star made his appearance.

The crowds often showed reluctance to depart finally and there was general getting in and out of cars, people wandering first this way and then that, abortive attempts to commandeer taxis ordered by other patrons and hazardous crossing of the streets. It was always interesting to watch an intoxicated cyclist attempt to mount and ride his vehicle, especially if he had a parcel to cope with into the bargain. Then it would be, “Look, he’s on! “Oh, hard luck, old boy!” “No look, this time, no, careful – Hooray – Whoops!”

Page 47

Now and then someone would casually pluck one of our geraniums to place behind and [an] intoxicated ear, whereupon Mother would rap sharply on the window pane and shake an admonitory finger. Usually though the command was, “Don’t let them see you peeping at them, or we may have trouble.”

There were other regulars along the Parade who were not necessarily patrons of the hotel, but part of the general scene. I well remember a gentleman named “Cough Spit”. He lived about four doors away and each morning he would come out of his gate coughing loudly, clear his throat two doors away and when he got to our place, spit on the footpath. Mother found that the loud comment “filthy creature.” fell on deaf ears, so one morning when the poor bloke was just reaching the grand finale of his performance, he became aware of a huge notice tacked on the telegraph pole outside our house – “Don’t spit!” – and he didn’t, but I don’t know how he managed his ad lib.

There was the “Squatter” who sat on the seat over the road, it seemed to us, all day and everyday. The “Sheik” strode purposefully along at the same time every morning and then we had “Moonface”. Pop named her that and then became rather emotional[ly] involved with her and the family insisted in using the name even after Pop had started calling her that “Poor little woman” instead. He called her husband “Crosspatch”, but he was quite a nice old chap really and we never adopted the name for him.

One lady who enjoyed a nice little evening promenade was the wife of a councillor. She often took the air with a small newspaper parcel under her arm. The parcels would be left quietly and efficiently on the Parade seats until she left one across the road from our place. Pop, investigating, found the parcel to contain kitchen scraps and returned it, under cover or [of] darkness and none too gently to the front porch of the lady’s residence. Thereafter her little walks took her further afield.

Page 48