- Home

- Collections

- CLAPPERTON GW

- Various

- Pukemiro - The Story of the ADB Williams Charitable Trust

Pukemiro – The Story of the ADB Williams Charitable Trust

Page 4

FOREWORD

Donald Williams entrusted the management of the Charitable Trust created by him shortly before his death to Nigel Robertshawe and me. Nigel died on 2 June, 1985, taking with him much knowledge of Donald’s background and his life in Dannevirke.

Peter Noble-Campbell drew my attention to the obvious that Nigel’s passing meant that there were very few people living who knew anything about Donald’s life, and that, as time went on, the Pukemiro Staton staff, and beneficiaries of Donald’s generous gift would know nothing of this unobtrusive man.

In these circumstances, it was felt proper to commission Mr J.J.L. Sulzberger to prepare a brief biography on Donald and Gwen Williams.

Mr Sulzberger has spent much of his working life in Hawke’s Bay as Editor of the Dannevirke Evening News and subsequently as Associate Editor of the Hawke’s Bay Herald-Tribune. He also is the author of The Richmond Years.

With his wealth of background, derived from his association with so many things in Hawke’s Bay, he seemed to be the natural choice as author.

I am delighted with the result, knowing the difficulties encountered with such a lack of written or recorded material.

The lack of records reduces much of Donald’s life to a record of brief incidents and much that is ordinary. Donald would not have wanted it any other way I am certain.

Marcus Poole

Dannevirke

March 1987

Page 5

INTRODUCTION

Early in December, 1985, three senior students of the Dannevirke High School became the first beneficiaries of the A.D.B. Williams Charitable Trust. Each was granted a bursary of $2500 a year for three years to assist them in university studies in subjects related to farming.

The announcement of the grants caught many people by surprise. It was not widely known that when Allen Donald Buchanan Williams (Donald Williams) died in 1983 he had left his considerable estate, including Pukemiro Station in the Otope Valley, for charitable purposes.

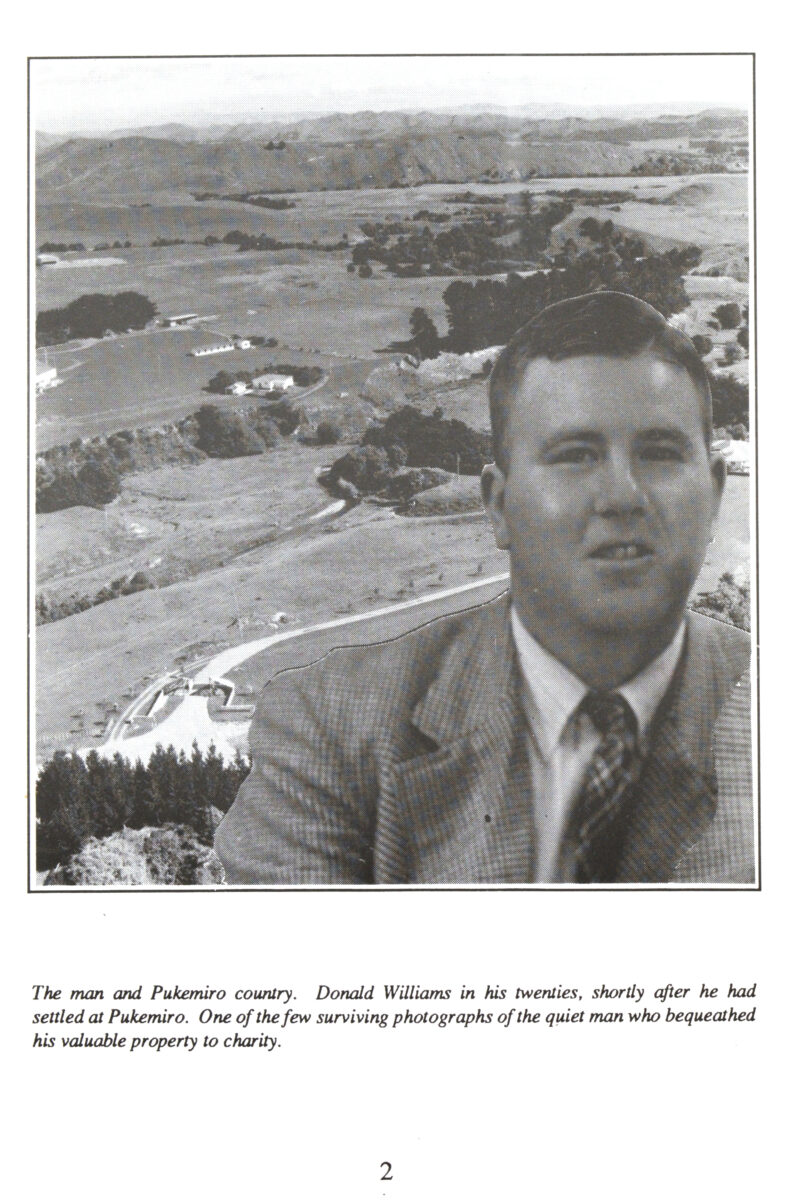

To many people in Southern Hawke’s Bay, Donald Williams was only a name. He had never been prominent or active in Dannevirke district affairs. Certainly, in the 46 years he had been associated with Pukemiro, he had given no hint that one day his assets would go to charity. When the announcement came it was almost a contradiction. In life, Donald Wiliams had earned a reputation for being careful with his money to the point of meanness. Generosity had never emerged as part of his nature.

He was a man who had lived with ill-health for many years. He died childless, his wife having predeceased him in 1981. He was a man who was difficult to get to know well. He was naturally shy, he was often inarticulate, though sometimes blunt to the point of rudeness, and he was careless about his personal appearance. He was sometimes regarded by people who did not know him well, or understand him, as being “somewhat odd”.

Deep down he was a sensitive man, often lonely and much misunderstood. In life he did not reflect the background from which he came, unless, in the end, by leaving his estate to a cause that would advance farming knowledge, he was expressing in his own way the deep love for the land that was part of his heritage.

Page 6

He left no diaries or letters that would throw light on his life. The following essay could never have been written without the co-operation and help of many people who knew and understood him, and who were prepared to share that experience, for this the writer expresses thanks.

For their part, the trustees of his estate who commissioned the work issued a simple brief: To record as far as was possible a biography of the life of Donald Williams and his parents so that what little was known of the man would not be lost. That entailed a journey back almost to the founding of Hawke’s Bay, and to Dannevirke when it was an infant village in the vastness of the Forty Mile Bush.

Donald William’s forebears filled a vital and visible role in the history of the area. He could not escape, even if only by association, from being part of it.

J.J.L.S.

The initial bursars of the A.D.B. Williams Charitable Trust. From Left: Sandra Fischer (Food technology), Edward Hardie (Agricultural Engineering), Joylene Whibley (B.Sc. specialising in Agricultural Science). All bursars were senior students of the Dannevirke High School and took up their scholarships at Massey University.

Page 7

CHAPTER ONE

The wealth was in the land and it demanded practical men of vision and of unbounded energy to release it. Hawke’s Bay was fortunate. In the central part of the province there were the Williamses, sons and grandsons of Pioneer Missionary-farmer the Rev. Henry Williams who had come to New Zealand in 1823 imbued with evangelical zeal and hard-headed business acumen. He was one of the first Europeans to plant crops in this new land and he and his descendants prospered.

In the south were the Knights and the Cowpers, strong-willed active men who recognised the potential hidden beneath vast tracts of bush, fern and scrub. They responded to the challenge.

These men were not dreamers. They were prepared to work for their own Utopias and they all contributed in large measure to the growth and development of Hawke’s Bay. They grew rich through their own efforts, and because, when the occasion demanded, they were not afraid to take risks. They were not always beyond criticism. They acted in good faith and they reflected the values of their own times. They all had one quality in common. They were self-assured men possessed of an unshakeable faith in their own ability and their own judgement. And behind all this was a shrewd and balanced sense of financial management.

The story of Pukemiro (the hill of the Miro Tree) and of Donald Williams’s long association with it, is inextricably linked with the achievements of these men. It had its genesis almost simultaneously in both Central and Southern Hawke’s Bay in the 1870s. It was around this time that Samuel Williams, Archdeacon of Hawke’s Bay, farmer extraordinary, rivers engineer

Page 8

and founder of Te Aute College, became owner of Mangakuri Station, 21,000 acres of rich sheep country on the coast 27 miles from Waipawa. And it was in 1877 that W.F. Knight and F.G. and H. Cowper purchased Kaitoki Station, 20,000 acres of bush, scrub and forest clearings five miles from the site of the infant town of Dannevirke.

Thirty years later both Mangakuri and Kaitoki were being broken up. The era of the great landholdings was coming to its end. From these divisions Mangakuri yielded Clareinch and from Kaitoki came Pukemiro. These events were greatly to influence the life of Donald Williams.

Samuel Williams came to Hawke’s Bay from the Otaki mission station in 1853 inspired with missionary eagerness and a promise from Bishop Selwyn and Governor Grey of 4000 acres of Crown land to be developed to finance Maori education. With his wife Mary he arrived at Te Aute to bitter disappointment. After an exhausting journey over rough tracks, across river fords and through virgin bush, they discovered that no shelter had been prepared for them. Nearly half a century later he was to comment wryly to the 1906 Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Te Aute and Wanganui School Trusts that “neither the Governor nor the committee of the Church Missionary Society nor the Bishop had taken into consideration that a missionary would require a house to live in.”

If Samuel Williams faced problems from the outset, he did not expect others to solve them for him. There was land to be broken in and a college to be built. He had brought with him a farming genius that had its origins in learning from experience. At the age of 15 he had worked some of the 11,000 acres of North Auckland land his father Henry, had acquired to provide for his growing family. Now, at the age of 31, his skills had grown and he was not, as were so many farmer settlers of the times, inhibited by adherence to the farming practices and the rural traditions of the England he had left as a child. He was to need all the skills he could muster.

His success as a farmer did not rest exclusively on his own practical knowledge of rural life and his undoubted ability as a judge of both land and stock. It rested to large degree on his ability to select the right men to

Page 9

oversee his undertakings.

One of these men was Donald William’s grandfather, Allen Marsh Williams, the fifth son of Samuel’s elder brother Edward, a respected judge of the Native Land Court.

Allen Williams came to Hawke’s Bay as a youth of 18 and for a time managed Keruru, the property of his cousin, James Nelson Williams. But Keruru was up for sale and Allen’s future was insecure. In 1875 he joined Samuel on Te Aute and before long was promoted, on ability, to become assistant-manager.

So began an association with Te Aute that was to last for 70 years. Hard work and a vision of what could be achieved were the keys to success. Te Aute flourished despite floods and droughts; despite plagues of caterpillars and crickets. Outbreaks of footrot and scab among the stock compounded the difficulties. Shorthorn cattle and Merino sheep were grazed to keep down regenerating undergrowth as more land was cleared. Later, Leicesters and Southdowns replaced the Merinos and Te Aute stock was acquiring an enviable reputation and was eagerly sought by breeders and runholders throughout New Zealand and Australia.

Samuel was not slow to recognise the qualities and the capabilities of his nephew. The work ethic was an essential ingredient of pioneer farming and Allen never spared himself. Within a short time he was promoted to manager, thus relieving Samuel of much of the responsibility of making Te Aute Station a profitable venture. It also left him with more time to devote to his missionary responsibilities and to the establishment of Te Aute College.

Allen did not fail him.

Working closely with Samuel he envisaged the broad sweep of development. More land was cleared, swamps were drained and thousands of willows were planted to protect the Waipawa river banks from erosion, but recurring floods were still a menace.

Page 10

Two early attempts by the Waipawa River Board to dam the river had failed so Samuel and Allen took over the task. It was a massive undertaking for those times. The dam was 500 yards long and 20 feet high at the river bank, but it was not beyond the capabilities of the Williams team. When the job was completed the lengthy task of draining Lake Roto-A-Tara began. Thousands of acres of land once under water were now available for farm development.

Allen was by now well-established at Te Aute and Samuel, prospering from Te Aute Station, was looking for new investments. By 1876 his nephew James had sold Keruru and had bought the 21,000 freehold acres of Mangakuri Station on the Waipawa coast. The property, for which he had paid £50,750 was then running some 18,000 sheep.

Samuel bought James out and put Allen in charge. If Mangakuri was to be brought up to its potential, Allen was the right man for the job. By 1900 Mangakuri was carrying 32,000 sheep and Allen was back at Te Aute. His brother George became Mangakuri’s new manager.

Allen continued to manage Te Aute and to supervise Mangakuri. In the 1870s he had married a Scottish girl, Annabella Milne Buchanan, who had left her home on Clareinch Island in Loch Lomond to come to New Zealand with her parents. There were five children of the marriage, two sons and three daughters.

Donald’s father, Douglas, was the elder son and spent his early years in the warmth and spartan security of the growing Williams community at Te Aute which was by now a focal point in the ecclesiastical, social and pastoral life of Central Hawke’s Bay.

Douglas was born to the land. The Wiliams farming tradition was almost as old as European settlement of the colony and Te Aute was at the forefront of farming method and technology of the times. But before Douglas could take active part, a sound formal education was regarded as essential. With his Anglican background it was inevitable that he should be enrolled at Heretaunga Preparatory School in Hastings.

The school had been founded in 1882 by William Rainbow and its

Page 11

curriculum embodied academic and theological values close to the conventions and the traditions of the Williams family. In the years ahead it was to fill an important role in the lives of successive generations of the family.

Douglas Williams as a lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion, 12th Canterbury Regiment. This 1917 photograph was taken shortly before he sailed for France where, as an infantry bombing officer, he was assigned one of the most dangerous postings in trench warfare. He was killed in action on March 27, 1918, a few weeks after Donald’s first birthday.

Page 12

In 1923 when the majority of the shares in the school were offered for sale, it was with the financial assistance of the Williams Family that the shares were purchased by the Anglican Diocese. Three years later the remainder of the shares were acquired by the diocese and in 1927 the school was amalgamated with Hurworth Preparatory School of Wanganui and the name changed to Hereworth.

Throughout the years it has maintained a close association with Wanganui Collegiate School. The Williams interest and influence continued as the school developed. The chapel, for which the foundation stone was laid in 1958, was a gift from Mr H.B Williams of Gisborne in memory of his son James Nelson Williams.

Douglas grappled with the three Rs at Heretaunga, but what was also of importance was that the school offered a grounding in the classics. A rounded education was desirable for the boy who could one day be expected to be a leader in the Hawke’s Bay farming community.

The Heretaunga years behind him, Douglas moved on to Wanganui Collegiate School. He was a keen student with an alert mind and a happy capacity to make friends easily and his developing qualities of leadership earned him the respect of his peers. He enjoyed the Wanganui years but the land was to be his life and with formal schooling completed he welcomed his return to Te Aute and the sunshine of Hawke’s Bay.

He revelled in the independence and the freedoms of rural life, but there were still disciplines to be observed within the Williams community at Te Aute. By now the days of struggle in breaking in the land were over and as the station’s reputation for the excellence of its stock continued to grow, so did its reputation as a farming training school.

The Te Aute farm cadet training school, presided over by Douglas’s father Allen, was breaking new ground in New Zealand. It was here that the serious business of preparing young men to cope with the practical as well as the theoretical aspects of Hawke’s Bay farming was carried out.

Douglas enjoyed no special privileges. He joined the other cadets, many of

Page 13

them his cousins among the sons of Hawke’s Bay landholders, and lived in the austere but adequate atmosphere of the cadets’ whare. His real farming experience was just beginning.

The Te Aute farm cadet training school remained in existence until 1914 when many of the Station’s leases expired and Te Aute Station itself was cut up.

Douglas’s future seemed to be assured. He had a sound formal education, he was growing in farming knowledge and in confidence, and the extensive Te Aute holdings offered ample opportunity for him to demonstrate his skills.

Archdeacon Samuel Williams. His vision and his energy, coupled with a shrewd business sense, made him one of the most wealthy and influential Hawke’s Bay personages of his time (Hawke’s Bay Art Gallery & Museum.

Page 14

CHAPTER TWO

While Samuel Williams was expanding his holdings in Central Hawke’s Bay, William Frederick Knight was similarly engaged in the southern end of the province. W.F. Knight was born at Old Milverton, Warwickshire, England in 1847, the eldest son of William and Augusta Williams. He was educated at Warwick College and until the family decided to emigrate to New Zealand was employed in an auctioneer’s office at Leamington. On October 28, 1862, at the age of 15, with his parents and his brothers, he embarked on the ship Devonshire at London.

One hundred and six days later he had reached Auckland.

It was a memorable voyage. Huge seas were encountered during a violent storm in the Bay of Biscay and the ship lost not only its main topmast, but also the 12 live sheep aboard which were to have provided fresh meat for the cabin passengers during the trip to New Zealand. The ship’s cow also became a casualty of the storm. The result was that the entire stock of fresh meat and fresh milk vanished overnight.

In the light of this calamity, it is of interest to note that a fellow passenger on the Devonshire was a young Scot named William Nelson. In the years to come he would establish the Tomoana freezing works at Hastings and play a significant part in the development of refrigeration which would completely change the face of food supplies on long sea voyages.

William Nelson and W.F. Knight struck up a friendship aboard the Devonshire that was to last a lifetime.

Page 15

W.F. Knight, entrepreneur, land-owner, sawmiller, businessman, and one of the dynamic personalities in the founding days of Dannevirke. His extensive landholdings in Southern Hawke’s Bay included the 2500 acre Otawhao block which was bequeathed to his daughters Clara Olive (Donald’s mother) and Freda on his death. Olive’s holding was re-named Pukemiro and purchased by Donald for $28,555 in 1951.

Page 16

Before the end of the 1860s W.F. Knight and his brothers had established themselves in business as general and farm contractors at Hastings and Clive. In 1866 he made his first visit to Southern Hawke’s Bay and to the tiny bush settlement that was to become Dannevirke. He saw at first-hand the potential of the forest yet to be cleared and the land that would one day be converted to rich pastures.

The Scandinavian settlement of the area in the 1870s saw him back in Southern Hawkes’s Bay. The Knight Brothers had successfully tendered for the transport of Danish and Norwegian settlers from the port of Napier to Norsewood and Dannevirke. It was a long creaking wagon journey over ill-formed roads and bush tracks. And again W.F. Knight was impressed with what he saw.

His chance came in 1877.

The Kaitoki block, then owned by Alexander Grant of Ruataniwha, was up for sale. The freehold was 16,145 acres of rolling hills and some bush-covered flats. There was fern and scrub on the open country. Kaitoki was then carrying slightly more than 4000 sheep. W.F. Knight, in partnership with F.G. and H. Cowper, saw the potential. They completed the purchase and set to work.

For weeks a pall of smoke hung over Dannevirke as fern and scrub were burned off and English grasses sown in the still-warm ashes. Where it was possible, the land was ploughed before sowing. Stock numbers rapidly increased and the bush that remained represented a fortune.

Kaitoki was part of the Forty Mile Bush, an ill-defined area sometimes referred to as the Seventy-Mile Bush. The names were apparently interchangeable, even in official correspondence. There was controversy then, and it still exists, about the extent of the area embraced by these names. Some sources place it as the land extending from the headwaters of the Manawatu River near Norsewood to the Ruamahanga River in the Wairarapa. Others describe it as stretching from the Takapau Plain to the Manawatu Gorge.

Even the name “Kaitoki” (food for the axe) roused some controversy when

Page 17

the official geographic form of the word became “Kaitoke”. F.G. Cowper would have none of it and he never compromised. He insisted that “Kaitoki” was the correct form and he insisted that it be retained for his landholdings.

There were huge problems of access when the Knights and Cowpers took over the land, but before long the first Knight Brothers’ sawmill was in operation. It was situated close to H.D. Knight’s home. “The Point” at the Manawatu River crossing.

More land was cleared and the joint Knight-Cowper venture flourished. But W.F. Knight was more entrepreneur than farmer. Soon more Knight sawmills were in operation and were a major source of employment in the Dannevirke area. It was the beginning of an involvement with the town and its development that was to last throughout his lifetime.

The Knights and Cowpers were by now well established and expanding their interests. Then a newspaper advertisement announcing that the Tahoraite [Tahoraiti] block, owned by D. McMaster, was to be sold was brought to W.F. Knight’s attention. He knew the land and he liked it. He did not hesitate. He bought the freehold and built his homestead on high ground overlooking the sweep of plain that stretched westwards to the Ruahines. Part of that land was later to become the site of the Dannevirke golf course. In those early days two of the most difficult holes on the course, “Crisis” and “The Cliffs” were on the eastern side of the road close to Tahoraite, and the rambling homestead itself, the scene of much of the district’s social life, was the venue for the presentation of the club’s trophies.

Tahoraite remained a well-known Dannevirke landmark until the late 1940s when it was destroyed by fire. It was aptly named. The Maori translates to “forest clearing”.

The Clive years held a special significance for W.F. Knight. It was in Clive that he met, and in 1822 married, Clara Wardley Brown, who, according to the newspapers of the time “had with her parents recently arrived from England”.

Clara Brown was a remarkable woman, years ahead of her time in terms of

Page 18

Golf was a major social activity at Kaitoki where the Knight homestead overlooked the Dannevirke Golf Club’s course. Two of the most difficult holes, “The Cliffs” and “Crisis” were on Knight land. These photographs show: Top, the opening of the 1905 season. W.F. Knight (with beard) is shown in the centre of the group. Donald’s mother, Clara Olive, is at her father’s left. Below, the presentation of trophies at the Knight homestead in 1909

Page 20

women’s emancipation. She had been one of the first women ever enrolled as a student at Oxford University, though no records remain to reveal details of her academic achievements in that illustrious hall of learning. From 1879 a few women were tolerated as members of the student body, but it was not until well into the 20th century that it was considered appropriate to confer degrees upon them.

Clara Brown, a clergyman’s daughter, had learned much and she brought to

Te Aute Station Homestead. Life was disciplined and often spartan, but there was some time for relaxation as shown in this turn-of-the-century photograph of the tennis courts. (Hawke’s Bay Art Gallery & Museum)

Page 21

what was then considered to be a distant and unsophisticated colony a love of learning for its own sake, a sense of culture and an appreciation of the quality of life. She set standards, and as far as she could, she insisted that within her own circle those standards be observed.

There were four children of the marriage. The sons, Bower and Eric, were to become well known throughout Southern Hawke’s Bay farming and business circles. The daughters, Clara Olive, Donald’s mother, and Freda, who was to marry Harry Cowper, were raised in the shadow of their mother.

There was a huge gap between the intellectual atmosphere Mrs Knight had known at Oxford and the practical down-to-earth reality of pioneering life in New Zealand. She was determined that her daughters should benefit from her own experience. She was also determined that they should make the best of what colonial society had to offer. Their formal education was completed at the exclusive and expensive Miss Bowen’s school in Christchurch and they then returned to Tahoraite.

Clara Olive, always known as Olive, and by a later generation simply as “Auntie O”, grew to be a strikingly handsome woman. She was vivacious, quick-witted and with a zest for life. She had assimilated much from her mother about the important part cultural interests and academic achievement could play in enlivening the day-to-day drabness of provincial life. Social respectability was not a quality lightly to be dismissed.

Given the landowning interests of the Williamses and the Knights, and the restricted structure of the society of the times, it was inevitable that she would one day meet Douglas Williams who was then still at Te Aute. They were married at Tahoraite in January, 1907. It was one of those special occasions in Hawke’s Bay life with the joining together of two of the province’s best-known and most respected families.

There were other dramatic developments that year. The Knight-Cowper partnership was dissolved and Kaitoki was subdivided. W.F. Knight and his sons took 7800 acres including the Otawhao Block. They were also expanding their other activities. Soon there were five Knight sawmills operating in the area and a few years later a further mill was established at Raetihi.

Page 22

It was also a period of land aggregation. The Knight Holdings eventually reached from the Manawatu River to include most of Tiratu. Also included was the homestead block of Mangatoro Station which had been broken up in 1902.

The Knight interests extended far beyond land ownership and milling. The Knight Brothers had financial interests in the Dannevirke Gas Company; they were major shareholders in Collett and Sons’ Foundry; they were connected with the Dannevirke-Herbertville Coaching Company and they had substantial real estate investments in the business area of Dannevirke. W.F. Knight was one of the prime movers in converting the Dannevirke Co-operative Association into a private trading company of which he became chairman. He remained chairman when the DCA merged with the then expanding Wairarapa Farmers’ Cooperative Association, though in the end, the depression years of the 1930s were to see what was a valuable asset diminish disastrously in value as WFCA shares were written down.

The Knight family had been involved with Dannevirke since the earliest days. They had seen it grow from a struggling bush settlement to a thriving town and they had been an active and important part of the driving force that brought the transition.

They had prospered in the process, and they were not ungrateful. When Dannevirke was constituted a borough in 1892, the mayoral chain and the mayoral chair were gifts to the town from the Knight brothers. The borough mottoes, “ne jupiter quidem omnibus placet” (even Jupiter can’t please everyone) and “magnum est vectigal parsimonia” (economy is a great source of revenue) are attributed to W.F. Knight, though Clara Knight, with her university background and her intellectual awareness, could well have been involved. The mottoes in themselves were not all that far removed from the Knight family philosophy. The marble tablets in St-John’s church, on which are inscribed the names of Dannevirke District Servicemen who died in action during the First World War, were also a gift to the town from the Knights.

When W.F. Knight died in Rotorua on April 27, 1920 after a heart attack while attending the celebrations to welcome the then Prince of Wales to

Page 23

New Zealand, the whole of Southern Hawke’s Bay was saddened. At his funeral service in St John’s Church, the Rev. G.B. Stephenson referred to him as “The Father of Dannevirke”. That may have been an overstatement that reflected the emotion of the occasion, but there is no question that Donald William’s grandfather on his mother’s side was a major and dynamic figure in the history of both the town and the district.

W.F. Knight had provided well for his children. The sons were well established on Knight land and the remaining 2500 acres of the Otawhao Block was bequeathed to Olive and Freda. For the next three decades it was farmed for them by Harry Cowper. Eventually it was subdivided to produce Awakeri and Pukemiro.

Page 24

CHAPTER THREE

On March 14, 1907, Samuel Williams died peacefully at Te Aute at the age of 85. He was a man who first and foremost devoted his life to his church and to mankind, and he had grown wealthy. His genius as a farmer and as a businessman is revealed by the fact that despite his unremitting attention to his work as a missionary and pastor, and the founding of Te Aute College, he left an estate valued at £429,566, a huge sum in those days. He had earned the respect, and often the admiration, of the Maori and Pakeha communities throughout Hawke’s Bay. He was undoubtedly one of the province’s outstanding pioneer figures.

Under the terms of his will those who had contributed so much to his success were not forgotten. Mangakuri Station was split up and the Clareinch Block, so named after Annabella Williams’s birthplace, went to Allen Marsh Williams, Donald’s grandfather. It was a generous benefaction, some 6000 acres of rich rolling sheep and cattle country sloping to the sea. But Allen Williams, firmly established at Te Aute and by now also owner of the 1200 acre Drumpeel Block, had no wish to move. He remained at Te Aute until his death in 1945 at the age of 93.

His son Douglas took over Clareinch and his future seemed to be secure. The homestead he built on the property reflected the lifestyle and the optimism of the times. Clareinch was planned in the grand manner of New Zealand country homes. It was a large rambling single-storey building with wide verandas giving access to a sweep of lawn and vistas of rich farmland. Space and grace were features of Clareinch. In the next few years it was to become a central point in the social life of wealthy Central Hawke’s Bay runholders as Douglas and Olive settled to their new life.

Page 26

Their first child, Bruce, was born at Clareinch and placed in the care of nanny Kathleen Ryan who was to become a beloved and trusted member of the Williams household for many years. Amy Margaret (Meg) followed in 1909, and again, nanny Ryan was placed in charge.

It was a boom time for farming. The outbreak of the First World War had brought an unprecedented demand for all the food New Zealand could produce and load on to ships for a beleaguered Britain. Prices remained high. Farmers had never had it so good.

Farming was part of the very fibre of Douglas Williams, but there were other traditions too. England was still the Mother Country and was now in danger. The spirit of patriotism ran high. Douglas was acutely aware that the Williams family had never flinched from duty. His grandfather, Henry, had served with distinction in Nelson’s navy. He had been a midshipman on the Barfleur in 1806 and a lieutenant at the Batte of Copenhagen. He had also taken part in the last naval engagement in the British-American war of 1812. It was only when peace came and he was retired as a lieutenant on half pay that he had turned to the church and to the adventurous territory of the South Pacific that had fascinated him since boyhood.

Samuel had also been involved in military affairs, though in a vastly different role. It was his deep understanding of the Maori way of life and the complexities of Maori land tenure that had enabled him to play an important part in keeping Maori-Pakeha conflict to a minimum during his years at the Otaki Mission, and later in Hawke’s Bay. And it was the trust he had earned through his deep understanding of Maoridom that had enabled him to avert widespread bloodshed during the Hau Hau uprising of the 1860s.

As the war dragged on and bogged down in the trenches of France, appeals to patriotism in New Zealand grew stronger. Many of Douglas’s relatives, cousins and uncles, were already serving in Palestine and in France with New Zealand British forces. His younger brother, Gordon, had been a volunteer and had sailed from New Zealand with the sixth reinforcement. He had been a sergeant in Gallipoli and was commissioned in the field.

Page 27

Now he was a captain serving in Palestine. Many of Douglas’s school friends from Wanganui were also serving overseas, as were many of the young men he had known in Central Hawke’s Bay. What was more, Douglas had his own sense of adventure that was not to be denied. He decided to enlist.

Olive was again pregnant and could not come to grips with Douglas’s reasons for wanting to join up. Farming was an industry essential to the war effort and farmers were exempt from conscription. Violence in any form was repugnant to her and she could not comprehend the driving forces deep within her husband that were prompting his actions. Suddenly the comfortable stability and security of the life at Clareinch was being shattered by the brutality reality of a distant war.

For the first time in her life she was on her own, and psychologically ill-equipped to deal with the trauma of this situation. With her husband absent, she had no desire to remain at Clareinch. She would move to Havelock North for the duration. Before Douglas entered camp he rented a family home in Duart Road, Havelock North.

Bruce was already a boarder at Heretaunga school and Meg, now aged seven, was to be enrolled at St George’s boarding school for girls, almost next door to the rented house. Meantime, Ernest Gilbertson, a mature and experienced farmer who already had a long association with Clareinch, would manage the property until Douglas returned. He was to remain there much longer than anyone could then anticipate.

Douglas entered Trentham camp with the rank of lieutenant towards the end of July, 1916, and was posted to the second battalion of the 12th Canterbury Regiment. His departure from New Zealand did not come as quickly as had been expected and he was able to make frequent visits to his family in Hawke’s Bay. In this atmosphere of uncertainty about when he would embark, Olive returned to the familiar surroundings of her parents’ home at Tahoraiti to await the arrival of the new baby.

Donald was born at Dannevirke on February 4, 1917, and like his brother and sister before him, was placed in the care of Kathleen Ryan. Even with all the uncertainties of those desperate times, it seemed that Donald’s future

Page 28

Donald as a boarder at Heretaunga School, Havelock North, before it was renamed Hereworth. He preferred the freedom of country life to the disciplines of boarding school.

was assured. The standing of the Williamses in Central Hawke’s Bay and of the Knights in the Dannevirke area, and the extensive landholdings and other interests of both families, meant that he had been born into a position of privilege. Financial security and social status were part of his inheritance. The war in Europe was a remote disruption that would pass.

Page 29

Douglas remained in Trentham Camp for almost a year. He embarked on the troopship Athenic at Wellington July 16, 1917. Donald was six months old when the father he would never know went to war. The Athenic reached Liverpool in September and by December 4, Douglas was with his battalion in France. He was almost immediately detached to the Gas School Corps and then to the Bombing School Corps for advanced instruction in trench warfare. He then returned to his battalion. The desperate German offensive of 1918 had already begun and the Second Battalion was ordered into the Auchonvillers sector in an attempt to stem the advance. Douglas was appointed bombing officer in the field on March 20, 1918. A few hours later he was killed in action.

He is buried at Greviller in France.

Olive, already having the greatest difficulty in coping with the stresses of separation, was now, at the age of 30, a widow with three young children, one of them only a year old. She learned to live with the shock and the grief of Douglas’s death, but the pain remained. Douglas had been the central pillar of her whole life and now that support was gone.

The New Zealand Free Lance of the period expressed what could well have been her own feelings. It said “Because he felt that duty called him, Lieutenant Williams gave up an unusually happy life and, after a few months on active service in France, he too has died on that field of honour where already many of his kinsmen have laid down their lives”.

Olive did not regard it as a field of honour, but she was determined that Douglas should not be forgotten. She commissioned a stained glass window for the chapel of his old school in Wanganui as a memorial to him, and endowed a scholarship in his name.

She had been left comfortably off, but that could not fill the gap. There were no worries about the running of Clareinch. Ernest Gilbertson was totally reliable and a trusted manager and she was content that he should be left to guide the fortunes of the property. But with Douglas no longer in the grand home he had built for her, she could not bring herself to return to Clareinch. A new home where the memories of the past did not constantly

Page 30

intrude would have to be found.

She vaguely knew what was needed to maintain some semblance of the lifestyle that had been built around Clareinch, but such a place in a suburban setting was difficult to find. Eventually she bought Endsleigh, a gracious house on ten acres of land off a pleasant tree-lined street in Havelock North. She was desperately in search of peach of mind as she set about rebuilding her shattered life.

With the assistance of a gardener she began planning a colourful and tranquil environment. Years later when she spoke of those stressful days she confessed that she “hated gardening”, but gardening kept her busy and provided a positive outlet for her energies and her creativity. As time passed, Endsleigh became the centre of a great deal of social activity. There were frequent tennis parties and a procession of visitors and friends from the Clareinch days and from Southern Hawke’s Bay. And in the quiet times there were cultural interests to be shared.

Donald was growing up under the watchful eyes of his mother and his nanny. He was a solid, healthy child, assertive in his own way and somewhat spoiled and overprotected. But the comfortable and sheltered existence at Endsleigh was soon to end. As soon as he was old enough he was enrolled at Heretaunga as a boarder, and with preparatory school behind him, went on to Wanganui Collegiate.

Whatever the initial sense of adventure, college turned out to be a lonely and traumatic experience. Donald had developed a love of the outdoors and did not relish the confines of the classroom. Neither was it in his nature to willingly embrace the cultural and social values which his mother accepted as an essential part of life. He was slow moving in his actions and hesitant in speech and, unlike his father, he found it difficult to make friends easily. He did not enjoy or excel in the highly competitive world of college sport.

In the years to come he seldom spoke of his schooldays, other than to leave an impression that they were best forgotten and that he was often the hapless victim of brighter and more active boys who made him the butt of their sometimes cruel jokes.

Page 31

There was never any doubt that his future would be in farming. From earliest childhood he had been made aware of the Williams’ and Knight traditions and encouraged to believe that one day he would take up land of his own. He had no other interests.

As a boy some of the happiest days were spent during the long vacations in the Otope valley with his aunt and uncle, Freda and Harry Cowper. The upthrust of the surrounding hills giving way to the flat and open land around Dannevirke and the backdrop of the Ruahines gave him a sense of freedom. What was perhaps more important was that here he found friends and acceptance, and perhaps some of the understanding that seemed so often to be absent in other spheres. He was building a bond and a love of the area that lasted as long as he lived. And in those days, too, there was a sharpening and empty awareness that unlike so many of his contemporaries, he had no father to turn to for guidance and advice.

Douglas had bequeathed Clareinch to Bruce and Donald in two-fifths shares, with the remaining fifth going to his sister Meg. Eventually Meg sold her interest to her brothers, thus leaving the way clear for an equal subdivision of the property. Years were to pass before that became a reality.

Olive remained at Endsleigh, but the good years had almost run their course. With the depression of the 1930s and with a succession of blazing summers followed by long, dry autumns, farming was feeling the pinch. Clareinch did not escape. Stock prices had plummeted to unrealistic levels. Prime lamb was bringing only 5½ d a pound and a fat ewe was worth only 5/-. Cattle prices too had slumped. Clareinch was surviving as well as any, but for Olive the future at Havelock North had suddenly become less attractive. Reluctantly she left Endsleigh and returned to Clareinch. A few years later, by the end of 1937, Endsleigh had been sold.

Meantime, Donald had completed his studies at Wanganui and had enrolled at Lincoln Agricultural College. Formal agricultural education, however, held little appeal for him. Years later when urging a young agricultural student to make full use of the opportunities offered by tertiary farming education, he confided regretfully that he had not done so himself. There were no second chances. It was the fun of undergraduate activity rather than the assimilation of farming knowledge and technology that had attracted him to Lincoln.

Page 32

But if Donald had left Lincoln at the end of 1936 still with much to learn about farming, his time there was not entirely wasted. The college years brought him a measure of independence hitherto unknown. From the age of five he had lived most of his life at two boarding schools and he experienced little of the warmth and sharing of family life. Lincoln added a new dimension and he was not quite sure how to handle it. And it was during those student days that he met Gwen Walls. That meeting was profoundly to influence his future life.

Elizabeth Marion Gwendoline Walls was a few years older than Donald, but that mattered little. She was a nurse from a farming background and in those days was imbued with a sense of fun and high spirits. Her exuberance and the warmth of her personality contrasted strangely with the normally taciturn Donald’s approach to life, but somehow there was a mutual attraction. Perhaps, for the first time, Donald had discovered someone with whom he could communicate.

Gwen was a product of her times. She placed a great deal of importance on her personal appearance and she enjoyed bright and colourful things around her. Life was something to be enjoyed and Donald responded, even when Gwen laughed irreverently at the more sober aspects of his family background. They were happy times, but Donald’s student days at Lincoln were almost at an end.

In February, 1937, he became a farm cadet under the tutelage of Peter Plummer on Tahuna, a few miles out of Waipawa. This was the ideal situation. Tahuna was typical Central Hawke’s Bay sheep and cattle country and Peter Plummer had a wealth of knowledge and practical experience, both on Tahuna and in Southern Hawke’s Bay where he had managed one of the Cowper properties. The conditions Donald could expect to experience on Tahuna would be duplicated on Clareinch.

Peter Plummer was not only a successful farmer. He was on the way up in the world of farm politics and was later to become New Zealand president of Federated Farmers and be deeply involved in private enterprise meat exporting as chairman of directors of W. Richmond Ltd in Hastings. But Donald was little interested in the behind-the-scenes manoeuvring of the rural power game. Whatever ambitions he held as a young man were

Page 33

centred solely only on the practical aspects of farming.

Peter Plummer, who had known him since boyhood, found him to be slow-moving and often inarticulate, but he was a willing enough worker and he seemed keen to learn. He had no other interests to entice him away from the land.

Donald remained at Tahuna for a year, often silent as he went about his tasks and a little difficult and awkward in company. In March, 1938, he left to broaden his experience as a shepherd on Glenross Staton on the Napier-Taihape Road. He rarely spoke of his experiences in that hard inland country and he did not stay long.

The following year he was back in Christchurch, more confident and self-assured than before, and making his own decisions about his future. On July 15, 1939, Donald and Gwen were quietly married there in St James’s Anglican Church. It was a family wedding with Gwen’s relatives and friends present. Donald’s side was represented by his mother and his brother and sister, but it was not a marriage of which they wholeheartedly approved. There was concern about the disparity in Donald’s and Gwen’s ages, but more importantly there were fears that their widely differing social backgrounds could create problems in the years ahead. Those fears were to turn out to be well founded.

Despite his half-share in Clareinch, Donald showed no intention of settling in Central Hawke’s Bay. The reasons for his not taking up his patrimony at the time are obscure. He did not get on well with his brother, Bruce, who had married a widow with two children and in 1937 had taken over the running of Clareinch. Olive, who had been living in the family homestead did not interfere. She moved from Clareinch and returned to the Knight family home at Tahoraiti where her mother now lived with Olive’s elder brother, Bower. That arrangement was to last until Tahoraiti was sold and Mrs Knight bought a property in Victoria Avenue in Dannevirke. Olive remained there until her mother’s death in 1948.

Page 34

CHAPTER FOUR

Two months before Donald’s wedding the Otawhao Block had been subdivided to give effect to the terms of W.F. Knight’s will. On May 10, 1939, the title of the 1385 acres that were to become Pukemiro Station, and also 16 acres of the Kaitoki No.3 Block, were transferred to Olive. The remainder of the Otawhao Block, now named Awakeri, was taken over by Wardley Cowper, son of Olive’s sister, Freda, who had married Harry Cowper. The 16 acres of the Kaitoki Block was considered to be land held in common as a site for a future Pukemiro-Awakeri woolshed and stock yards.

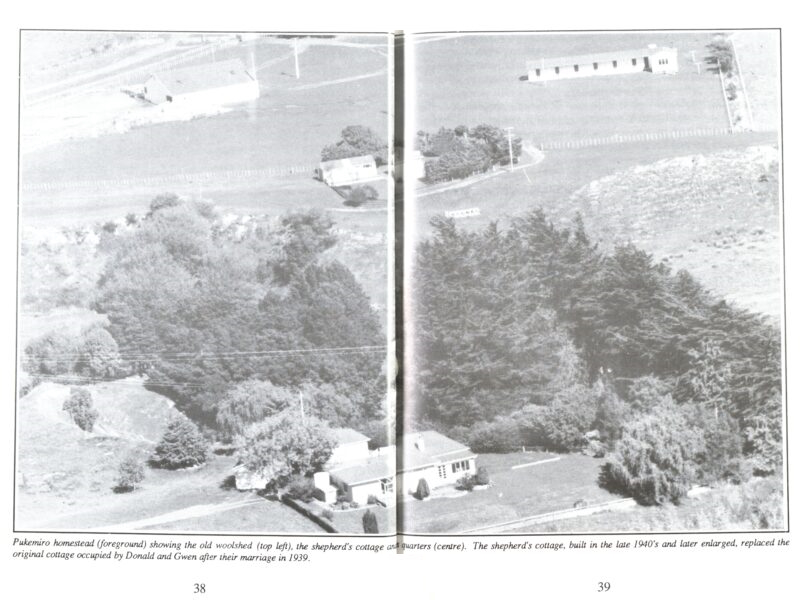

It was to Pukemiro rather than to Clareinch that Donald turned with his bride. They moved into what had been a shepherd’s cottage across the creek from where the homestead now stands. The living conditions were basic and primitive. The cottage was a ramshackle building that had been allowed to fall into disrepair over the years it had been left unoccupied. The piles had sunk, it was draughty and the roof leaked. There was little incentive for Gwen to do anything more than make it habitable but she made the best of the conditions.

One of their first weekend visitors was Donald’s mother. Gwen was about to discover just what was meant by adhering to social standards. The

Page 35

cottage was never designed for entertaining but Olive was unbending. It must have been the first occasion in those surroundings that a guest insisted on dressing formally for dinner!

At the time there was no certainty that Donald and Gwen would remain in Southern Hawke’s Bay, but major changes were not far away. Donald’s interests in Clareinch were being supervised by the trustees of the Douglas Williams estate. They were Donald’s uncle, Eric Knight, and Napier accountant Julius Sandtmann. Donald seemed content to leave matters entirely in their hands.

Things were not going well at Clareinch. Ernest Gilbertson’s expertise and his deep working knowledge of the property were now gone. Bruce had different priorities and his own ideas about how the station should be run.

They were good years for farming. The outbreak of the Second World War had seen prices boom and a return to commandeer purchasing as Britain again appealed for every ton of meat and wool that could be found for export. But while farmers, generally, were prospering, the returns at Clareinch were below expectations. The trustees were concerned that neither the land nor the stock were competently being managed.

By the middle of 1944 the trustees’ concern had deepened. Bruce could manage the property according to his own standards, but Donald’s interests had to be protected. Eric Knight approached Peter Plummer and expressed the trustees’ disquiet. The result of that meeting was that Peter Plummer agreed to become supervisor of Clareinch and for the next nine years held that position. It was no sinecure. Bruce was reluctant to listen to, or accept, outside advice or to act upon the supervisor’s recommendations.

In these circumstances, the trustees’ concern turned to alarm. On April 21, 1945, they had Clareinch valued and soon after that, the property was subdivided. Bruce retained the homestead block and Donald took the share that was to become Pawanui.

The name was well chosen. “Pawa” was apparently a corruption of the Maori “paua” for shellfish, to which was added “nui”, the Maori word for abundant. Pawanui swept from the upthrust of pastoral land to the beaches where, in the early days the wool clip from Mangakuri had been loaded into

Page 36

surfboats and rowed to ships lying at anchor beyond the dangerous reefs. Shellfish abounded in those reefs.

But Donald was never to farm Pawanui on his own account. A cottage was built on the property and on Peter Plummer’s advice, Douglas Malthus was appointed farm manager. It was a happy choice. Pawanui never looked back.

Olive was still with her mother at Dannevirke, but Mrs Knight was now nearly 80 years old and Olive was being forced into the realisation that she must seriously consider her own future. Her paternal inheritance was Pukemiro and in the normal course of events it seemed likely that Donald would one day take over Pawanui. It became a priority to have a homestead bult on Pukemiro.

After the grace and space of Clareinch, and the character of Tahoraite, Pukemiro was an unpretentious dwelling. It was a single-storey stucco building, scarcely visible from the road and reflecting in part wartime shortage of building materials and wartime building restrictions then in force. But it was comfortable enough, built to the sun with large windows facing across a strip of lawn to a wooded bank beyond a narrow gully. And reflecting Olive’s plans and expectations, the house included a separate flat designed to provide quarters for a maid.

Austere it might be by Clareinch standards, but there were plans for beautification. A landscape gardener was engaged to lay out a paved terrace and provide plans for future plantings. Those plans were never used.

It was in the 1940s, too, that the Pukemiro woolshed was built. It was a problem at the beginning and was to remain a problem for the next 40 years. It was a joint Pukemiro-Awakeri project, though the title of the land was still registered with Pukemiro. It was not until October, 1957, that a half interest in the land was transferred to Awakeri, then being farmed by Derek Cowper.

The shed was built of Matai and Totara milled from the remaining stands of native bush in the gullies of Pukemiro. It was not well designed, and even more badly built and it reflected the continuing shortage of building

Page 40

materials. There had been totara post-and-rail stock yards on the site and these were put to use. The timber from them was used to construct the new holding pens. No effort was spared to cut down on expenses and make do. In the long-run, the economies of those days were to turn out to be costly.

In the years ahead, Donald never impressed with either the design or the construction of the shed, was to nurture a nagging bitterness about real or imagined inequities in its use. As stock numbers increased, additional pressures were exerted on the shed itself, the yards and the paddocking. Donald was convinced he was on the losing end.

It was not until after his death that the problem of the woolshed was eventually solved. The original shed was designed to handle a flock of around 4000 sheep, but as Pukemiro was developed and stock numbers increased, it became increasingly obvious that it must be replaced.

In the mid 1980s Peter Noble-Campbell, by now supervisor of Pukemiro, and the new manager of the station, Kevin Murphy, made an exhaustive survey of Woolaway sheds then in use, and of design modifications that would be appropriate to Pukemiro’s requirements. Stock numbers had by then more than doubled to around 9000.

The estimated price of the new building, including redesign, erecting new yards and installing a power feeder line, was in excess of $100,000.

It was decided to go ahead with the project. The construction was completed and the new shed and yards came into use for the first time in 1986. The actual cost was below the estimate. The price for the job was $90,000.

Awakeri Station was not involved and continued to use the original shed which remains partly owned by Pukemiro.

If there were frustrations, there were happy times at the old woolshed too. In the 1950s it was the venue for many social gatherings and dances as Dannevirke conducted a queen carnival to raise funds to build a war memorial sports centre. These were times Donald and Gwen both enjoyed.

Page 41

For a brief time the cares and worries of Pukemiro could be forgotten. There was music and laughter as a welcome relief from the drabness of a lifestyle in which people did not laugh very much, and in which invisible barriers seemed to keep neighbours at a distance. There was, too, the generous hospitality of the organisers of these events who were happy to show their appreciation for the use of the property. And the police, recognising a good cause when they saw one conveniently failed to notice many of the fund-raising activities.

Page 42

CHAPTER FIVE

Olive stayed on with her mother in Dannevirke when the Pukemiro homestead was completed and Donald and Gwen moved in. Pukemiro was in good heart. Harry Cowper was a capable farmer and had managed the property well, though a backlog of development work awaited attention. There were pockets of heavy scrub, perhaps 200 acres in all to be cleared and in some areas gorse had taken hold and was spreading. More subdividing fences were needed to improve facilities for stock management.

There was plenty to do. The tasks ahead were not much more than routine, but even in those days Donald found it difficult to motivate himself to get on with the job.

For her part, Gwen now released from the cramped and inadequate quarters of the cottage, was taking an active interest in transforming the new homestead into a home. Her early interest in gardening was suddenly given a new impetus and soon the bank below the lawn was a blaze of floral colour. But this initial burst of enthusiasm was not to last. Unknown to them then, she was developing a serious mental illness that was to recur time and time again.

Page 44

There were breaks in the everyday farm routine when visitors arrived. Wartime petrol and food rationing were still in force and Gwen’s sister, Idris, then working in Masterton, would arrive by rail and spend weekends on Pukemiro. Sometimes Gwen’s two nieces would spend a few days on the farm and soon became firm friends with Donald. The place always seemed empty when they returned to Auckland. And as visitors departed, Gwen’s natural generosity and understanding would reveal itself. There were always gifts of farm produce, and sometimes a petrol coupon or two, to hep them on their way and make life a little easier.

Gwen’s illness worsened. She began to lose interest in her surroundings and the garden she had established became neglected. She seldom picked up the embroidery that formerly had occupied many of her leisure hours. Soon it was apparent that she would have to receive institutional care.

She was admitted to mental hospital and Donald was left disconsolate, lonely and confused. When his maternal grandmother, Mrs Knight, had died in 1948, Olive had returned to Havelock North. Now she came back to Pukemiro. She had come to Donald’s aid, but it was never a close relationship. More than once he confided to the few people close to him that he really did not know or understand his mother. They moved on different planes and communication was always difficult. The childhood years of separation had left their mark.

At that time it seemed that Gwen’s illness was incurable and that she would never resume a normal life at Pukemiro. That did not take into account rapid advances then being made in the formulation of new drugs and new and effective methods of psychiatric treatment.

For the next two years, while Gwen remained in hospital, Olive stayed on at Pukemiro, but living with Donald did not provide the lifestyle to which she was accustomed. Gwen was beginning to respond to treatment and the clouds seemed to be lifting. Olive returned to Havelock North. That time with Donald was the longest she ever spent on Pukemiro.

A Mrs Brown from Dannevirke was installed as Donald’s housekeeper, though it was only an interim arrangement. She did not stay long, but her presence bridged the gap until Gwen, apparently restored to health, was well

Page 45

enough to come home.

The illness was not beaten. There were periodic relapses which demanded that Gwen return to hospital. On those occasions, Donald would become morose and withdrawn. Sometimes his mother would pay short visits while Gwen was absent, but for the most part, Donald’s simple wants were met by whomever occupied the farm cottage at the time.

His uncertainty increased and he was content to leave the management of his financial affairs to his accountants. Perhaps he was taking the easy way out and avoiding decision-making, or simply because he lacked confidence. It could also have been because his own health was deteriorating.

He was already overweight, his eyesight, which had never been strong, was troubling him and he was experiencing the first impact of non-insulin dependent diabetes. These problems were compounded by the fact that he was reluctant to seek medical advice or help, and his condition was not helped when he continued to enjoy a few beers whenever he went to town. He seemed content to let matters drift.

By now he was well established in the Dannevirke area and he had no inclination to leave. There is nothing to suggest that any member of his family ever encouraged him to leave Pukemiro and take over his own property. Instead, whatever discussion ensued centred on him selling Pawanui and purchasing Pukemiro.

Towards the end of 1950, agreement was reached for a rearrangement of family landholdings which would finance the transactions.

Donald sold Pawanui for the sum of £23,025 to a newly formed company, Pawanui Land Company Limited and retained a one-third interest in that company. The other shareholders, each also holding a one-third interest, were his sister Meg, and Pawanui Land Company Trust with the sole beneficiary being Meg’s daughter, Mrs Susan Lindemann.

At the same time, Donald purchased Pukemiro from his mother for the sum of £28,555.

Page 46

By November, 1951, the legal formalities for both purchases had been completed and on February 29 the following year the Land Valuation Committee consented to the transactions.

Douglas Malthus continued to manage Pawanui for the new company which retained the property for the next 13 years. In 1983, Pawanui was sold to Douglas Malthus and his son.

Bruce lived on at Clareinch until his death in 1973. There were no children of his marriage but he had married a widow with a family of her own and the property eventually passed to them. Clareinch homestead remained occupied until about 1980, but it was too large for modern living and deferred maintenance had become a major problem.

The house was vacated and left empty for the next four years. There was concern that the rich panelling and the ornate mantels and doors of another era would permanently be lost as the building further deteriorated. Clareinch was demolished and the rich interior fittings that had contributed so much towards making it a showpiece home when Douglas Williams had it built nearly 80 years earlier were salvaged.

The property that had been purchased by Samuel Williams in the 1870s had at last passed out of Williams family hands.

Page 47

CHAPTER SIX

Pukemiro had entered a new era and one of the imperatives was to bring the scrub under control. A start had been made before Donald took over the property but the scrubcutting contracts had by now expired. Negotiating contracts, and especially with the calibre of gangs experienced in this work, had Donald out of his depth.

He did not seek advice. As he saw it, to have done so would have been interpreted as an admission of his own inadequacy. No one volunteered advice either, though there were neighbouring landowners who had been through the exercise before and could have been helpful. Rightly or wrongly, Donald felt that he was being placed under peer-group scrutiny and that no one would be unduly concerned if he made a mess of it.

He pushed ahead, uncertain of his ground and ended up on the losing end. He found himself dealing with some hard-headed gangs ready to exploit his inexperience with the result that in some cases, he was paying substantially more than the job was worth, while at the same time others were content to get on with the job at reasonable rates. He felt that not only had he been cheated, but in the process he had been outwitted and had made a laughing stock of himself.

Page 48

He was committed to live with the agreements he had made, but he never forgot the incident which had left him angry and to some extent embittered.

Years later some of his closest associates interpreted the disaster of Donald’s scrubcutting contracts as the trigger-point for the development of the streak of caution and petty meanness that was to characterise his attitudes and his behaviour from then on. When he had needed help it had not been forthcoming. Had his neighbours been prepared to deal with him more on equal terms as a practical farmer, things could well have been different.

Gwen’s health was again causing concern. There was a sense of isolation at Pukemiro, heightened by the fact that other landowners in the area made little effort to draw Donald and Gwen into any community of interest. Members of Donald’s family seldom called. When they did they were welcomed, but they had grown apart. The nucleus of family had not held and they met almost as strangers with little basis for mutual understanding.

Donald and Gwen had a brief holiday in Australia but the change in scene did little to improve Gwen’s condition. It was soon clear that she would have to be readmitted to hospital.

Donald resigned himself philosophically to the situation. He did not complain. He was on his own, engulfed by loneliness and his life seemed to lack direction. He had no enthusiasm for work and managed as best he could with the help of the couple now occupying the cottage.

He health continued to get worse. He lacked the energy and the drive to give Pukemiro the attention it required to make it a thriving and profitable undertaking. The essential aerial topdressing programme was maintained and the fences were in reasonable order, but other than that, development work was at a standstill. The scrub was by now virtually eliminated at high cost, but the subdivision of paddocks and attention to pasture and stock management were let go by default.

This state of affairs did not pass unnoticed in the district. There was criticism of his lack of decisiveness and of action, but little understanding of the reasons for it and no offers of help. Even had he wished it, there were

Page 49

few people in the area with whom he could discuss his problems. And his critics, well aware that Gwen was ill, failed to recognise that Donald was under severe emotional strain and that he, himself, was far from being well.

Gwen returned from hospital temporarily restored in health, but lacking vigour and with little inclination to become involved in housekeeping. Life at Pukemiro settled to a slow and mostly monotonous routine. Wool prices were holding firm and lambs sent to the freezing works were bringing good returns, but Pukemiro was not prospering. Donald was simply not managing the property well. His physical limitations no less than his attitudes to life were holding him back. He could not motivate himself to push ahead with work programmes that would increase production or improve the quality of his stock. Pukemiro was slipping back.

His reputation for penny-pinching increased. He flatly refused to spend money on anything other than farm essentials and this carried into his personal life. There were no luxuries, and Gwen suffered too, though she was never heard to complain.

What little social contact they had with neighbours further diminished. Donald said little, but he felt acutely that neither he, nor Gwen with her forthright manner and her recurring illness, were socially acceptable. If they did not find the companionship they both desperately needed among the other landowners, they were not without friends. They found warmth and friendliness with workers on other properties in the area, and they both enjoyed the freewheeling good humour of Dannevirke’s hotels where Donald earned an incredible reputation and created legends for his ability to consume massive quantities of counter-lunch in record time. He loved eating, and he liked food in huge quantities.

They found companionship, too, with the Maori community at Kaitoke. The Kaitoke pa was close to the Otope Road junction on the Dannevirke-Weber route and Donald had to pass the gate on his way home from town. Often he would stop and fill in a pleasant hour. Here he found he was taken at face value and it was easy enough to find shared interests. Like Samuel Williams he had a healthy respect for Maori values, though he lacked his great-uncle’s deep understanding of Maoritanga. He was always made to feel welcome at Kaitoke and he appreciated the open-handed Maori hospitality

Page 50

and easy going approach to everyday situations that contrasted sharply with his own upbringing.

In all of this, it often seemed that Donald was rebelling against, if not rejecting, the conventions of his own social background.

The duckshooting season was always a source of enjoyment for Donald. Each year he would look forward to the company of people with whom he had little contact at other times. They were mostly townspeople, appreciative of the opportunity to shoot over Pukemiro’s dams. They would return year after year, their activity beginning in April as they prepared their mai-mais and Donald welcomed this diversion from routine farm life and took a close and lively interest in all the activities. Because of his failing eyesight he could not himself take part in the shooting, but he joined fully in the spirit and often the excitement of the occasion.

There were, of course, some minor rewards. The duckshooters came well prepared to stave off the early morning chills and they made sure that Donald shared in their warming liquid refreshments. In addition he was partial to roast wild duck. Each group shooting of Pukemiro made certain that Donald received his full share of the bag and no one dared to defect. To have done so would have been to risk losing access to one of the best shooting places in the district. Late payment of this annual tribute was never kindly received and when he retired to town, the established tradition continued with Donald often in high good humour as he helped out with the plucking.

Throughout the latter part of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s Pukemiro’s fortunes continued to decline. Modern methods of pasture management and stock control had not been implemented and nothing had been done to improve and build up capital stock. Strangely enough, while his own stock was in poor condition, Donald was never happier than when inspecting well-bred and healthy farm animals.

By the middle of the 1960s, neighbours, friends and stock agents were openly expressing concern. Reluctantly, Donald was being forced to accept that if Pukemiro was to prosper he could no longer manage on his own. The accountant’s figures reinforced the advice he was already receiving. This

Page 51

was the turning point. When his accountants entered the discussion and gravely referred to Pukemiro’s shortcomings, Donald took notice. He agreed that more help would have to be engaged.

The success of such a move hinged on getting the right man for the job and Donald did not choose well. He hired a man who appeared to have the right qualifications, but once installed in the Pukemiro cottage, he too, seemed content to let matters drift. There was no dramatic improvement and Donald was left to complain that when the new man was most needed around the place he was difficult to find. His frequent trips to Dannevirke were a constant source of irritation and Donald was fast coming to the conclusion that the whole idea of reconstruction was, in effect, a colossal blunder. It was while he was ruefully contemplating this situation that he first met Peter Noble-Campbell.

Peter Noble-Campbell had come to neighbouring Tara Station as a single shepherd in 1963. Before long he was chatting to the normally taciturn Donald over the boundary fence. Neither knew it then, but they were laying the foundation for a long-lasting relationship that was to have a profound effect on Pukemiro in the years ahead.

Donald did not make friends easily but he liked the young and vigorous newcomer who was hard-working and who had a practical commonsense approach to farming. Donald did not hesitate to call on him for help when the occasion arose. There were many times when Peter Noble-Campbell would climb the dividing fence and help out with mustering and other chores. Donald was always grateful, though his gratitude didn’t extend to his chequebook.

By this time it was clear that sporadic help was not enough to get Pukemiro off the steep downward slide. There was talk of up to 300 dead sheep being counted on the Pukemiro flats, starved to death through lack of sound farm management. The figure could well have been exaggerated, but it indicated the way things were going. Other stock was desperately in need of attention. In addition to the concern of the neighbours who could see for themselves what was happening, the SPCA was becoming interested.

If Pukemiro’s fortunes were to be reversed a farm manager with full-decision-

Page 52

making authority would have to take over. Such a man would have to be able to assess the situation as it was and recognise the potential of the land. And it was essential that, in addition to having practical farming skills, he must be prepared to work.

The time was fortuitous. While Donald was struggling to find a way out of his dilemma, Noel Nilson and his wife Phillipa were at Pongaroa considering their own future.

Page 53

CHAPTER SEVEN

Noel Nilson was stock manager for Toby Humphreys on Wairakau at Pongaroa and happy in his job. But the Nilsons had five young children and the relative isolation of Pongaroa from secondary schools was causing them concern. In the early 1960s farm wages were not high and the cost of boarding school for the older children was prohibitive. If the Nilsons could find a suitable position on the land close to a town with a secondary school their problems would be solved.

While they were considering this, they were approached by Don Galloway, a stock agent for Williams and Kettle, who told them of the situation at Pukemiro. If Donald was to appoint a manager with full responsibility, the Nilsons would be interested. Pukemiro, only a short distance from Dannevirke, appeared to be the ideal place. Noel Nilson applied for the job.

When the Nilsons were interviewed their meeting with Donald and Gwen came as a shock. Donald was inarticulate and abrupt. His physical appearance was not helped by his shabby and untidy dress. Gwen was untidy too, and the house was a mess. The garden had by now disappeared and grass and weeds grew up to the windowsills. The place was overrun by cats.

Page 55

Such things, however, were of little consequence. Donald, his health still failing, and disillusioned by the poor performance of the man he had previously hired, was cautious, but Noel Nilson impressed him. What was of equal importance at the time was that Noel Nilson had fallen in love with Pukemiro at first sight and saw immediately the potential awaiting to be developed.

He got the job and Donald issued only one sweeping instruction. “All I want you to do,” he said, “is make this place pay for itself”. This single sentence contained the tragic admission that managing Pukemiro was beyond Donald’s capacity. A thousand acres of rolling hills and 300 acres of rich flats had run down to the point at which it could no longer support two people.

Noel Nilson cheerfully and confidently accepted the challenge, but Donald had struck a hard bargain. There was to be no subsidised superannuation scheme and no medical insurance. No account was taken of the fact that the Nilsons had taken a salary cut to come to Pukemiro. That was their choice and Donald was calling the tune. He would scrupulously observe all the terms of the contract but he would not go one penny beyond that. Even a direct approach from an insurance company pointing out the advantages to an employer in making some concessions in order to keep a good employee happy in his job failed to move him.

The Nilsons moved into Pukemiro and tackled a massive clean-up task to get rid of the scars of years of neglect and deferred maintenance. The neighbours were prepared to help. They arrived with buckets and scrubbing brushes and set to with a will. The Nilsons were off to a good start.

Donald and Gwen had left reluctantly. Most of Donald’s adult life had been spent in rural surroundings and the prospect of life in suburbia held little appeal. He had come to terms with his situation. With failing health he accepted that there was no prospect of ever returning to life as he had known it on the farm. He bought a modest but comfortable house in Victoria Avenue, once one of Dannevirke’s most prestigious streets but now succumbing to the ravages of time and change. Prestige areas meant little to either Donald or Gwen. They would have been as equally content, or

Page 56

discontented, in any urban setting. And now that Donald’s failing eyesight ruled out the possibility of his ever driving again, the new home had the advantage of being within easy walking distance of the town’s shopping area.

Donald found it difficult to adjust. He was content enough to leave the day-to-day running of Pukemiro to Noel Nilson, though he maintained a continuing interest and kept a watchful eye on the patterns of change. The few remaining stands of native bush were now jealously being guarded and the manager, in addition to primary considerations of farm management, had plans to improve the environmental quality of the dams on the property. Donald quietly approved but said little. He was well aware of the progress being made.

His health was a constant worry. He did little to help himself. He was erratic in taking medication and he refused to take seriously all advice to bring his diet under control. The result was that at a time when his weight should have been held in check, he was becoming even more obese.

Gwen’s health, too, was a continuing cause for concern. As time passed it became necessary for her to be readmitted to mental hospital from time to time. There was nothing Donald could do to assist but his deep sense of loyalty to his wife in these times of stress was unquestioned.

His mother now came less frequently when he was left on his own. She had developed her own interests in Havelock North and Hastings. The Rudolf Steiner system of education, and the associated Hohepa homes for the mentally retarded, occupied much of her time and she had become a member of the Anthroposophical Society which also stemmed from the Steiner philosophical teachings. She actively retained these interests until her death in 1970.

Donald would often break the monotony of town living by visiting Pukemiro, though never without an invitation from the Nilsons, or before letting them know of his intentions. He would arrive on the morning school bus and potter around the homestead or woolshed. By now his physical condition was such that any major exertion was out of the question and he could not venture into the hill country. He enjoyed these visits and

Page 57

was appreciative of the huge farm meals provided by Phillipa Nilson. In the late afternoon he would return home, again travelling by school bus.

On some occasions he would arrive with stock agents from Williams and Kettle, the stock and station agency founded by a distant cousin, Frederick Williams, who had financed the undertaking with a bank guarantee of £1000 underwritten by Samuel Williams. Such visits, often in the company of Don Galloway, gave him additional opportunity to discuss farming matters with men who were closely in touch with trends throughout the whole area. He liked to be informed, but whatever opinions he formed for himself, he was content still to leave Noel Nilson in charge at Pukemiro.

Things were going well, but when they went wrong, as they sometimes did, he did not complain or apportion blame. “Every man has to make a mistake now and again” was the only reaction.

Under the new manager’s guidance, Pukemiro was prospering. Stock numbers were rising and sheep and cattle were going forward for sale in better condition than ever before. Donald consented to the purchase of a farm ute. That represented an expense that previously would never have been considered. Donald didn’t like big expenses, but the purchase of a vehicle was at least tax deductible!