- Home

- Collections

- CLAPPERTON GW

- Various

- Vegetation of the Ruahine Range

Vegetation of the Ruahine Range

THE FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE

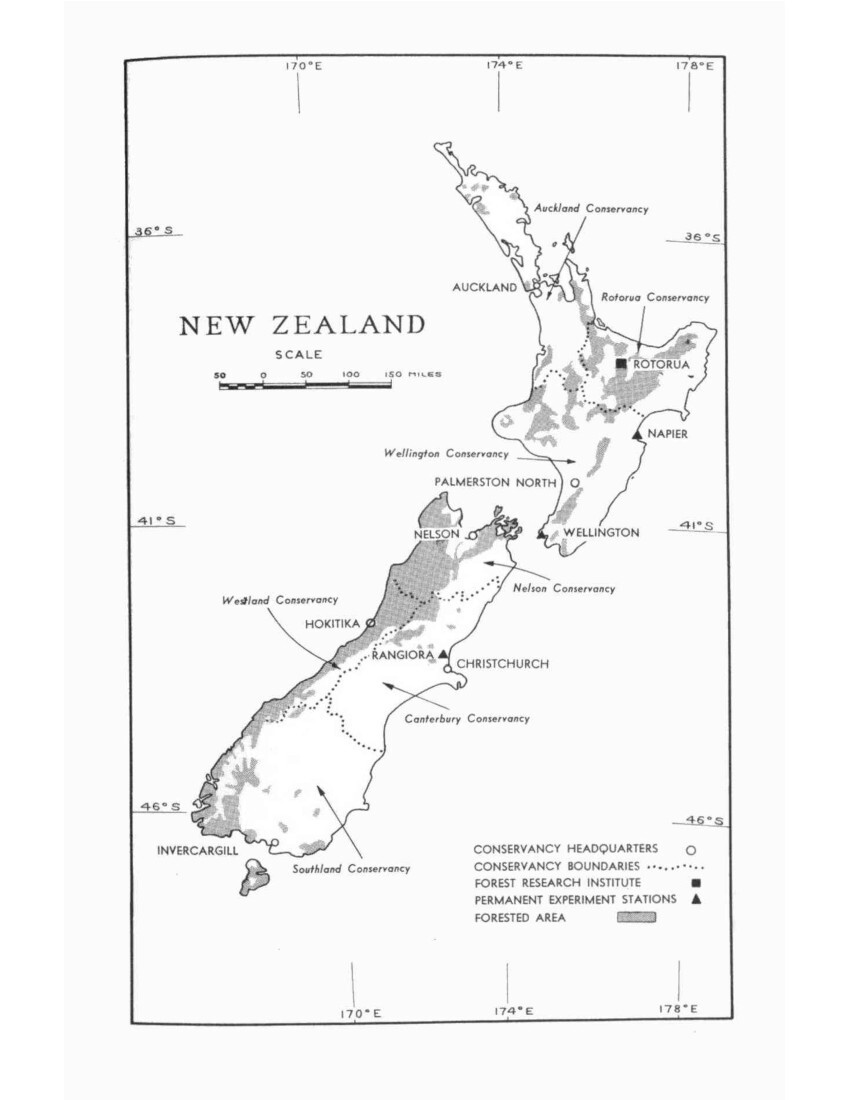

THE functions of the Forest Research Institute are to supervise all forestry and forest-products research carried out by the New Zealand Forest Service, and to undertake a programme of research approved by the Director-General of Forests. The work of the Institute is organised under six branches: Silviculture, Pathology, Forest Management, Protection Forestry, Forest-tree Improvement, and Forest Products. Most of the professional staff, together with field and auxiliary-service personnel, are based on Rotorua, but subsidiary Experiment Stations are located at Rangiora, Napier, and Wellington. All come under the charge of the Director of Research, who is directly responsible to the Director-General of Forests.

The work of the Institute is reported in its Annual Report and through the following media: New Zealand Forestry Research Notes, New Zealand Forest Service Technical Papers, and New Zealand Forest Service Bulletins. Papers published in scientific journals may be issued in a Reprint series. These publications are available from either the Director-General of Forests, Private Bag, Wellington, or the Director of Research, Private Bag, Whakarewarewa, Rotorua.

S.D. RICHARDSON,

Director of Research

TRANSACTIONS

OF THE

ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND

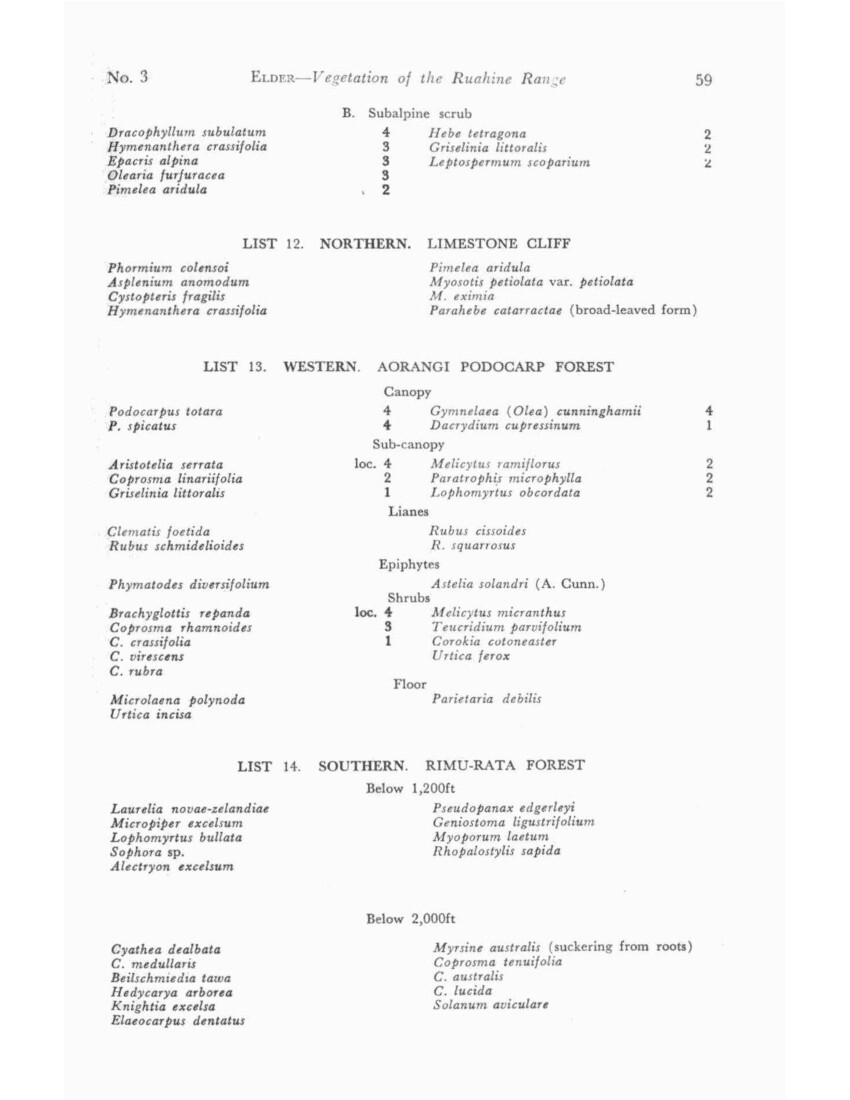

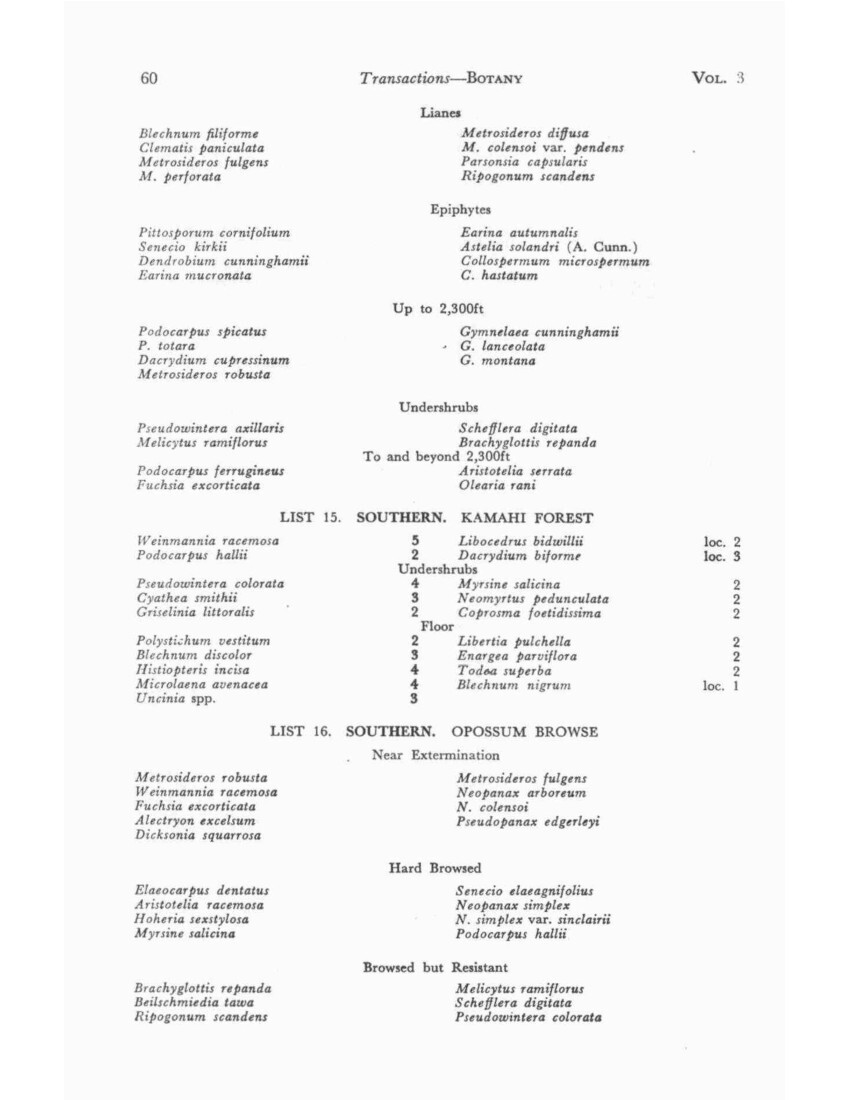

BOTANY

VOL. 3 No. 3 APRIL 14, 1965

Vegetation of the Ruahine Range: An Introduction

By N.L. ELDER

(Received by the Editor, 25 March 1964.)

Abstract

THE Ruahine Range forms a vegetational bridge between the volcanic plateau and Cook Strait, that is from the driest and sunniest environment in the North Island to one of the cloudiest and wettest. Past and present changes are conspicuous and their causes various. This paper summarizes observations over the last 30 years and is presented in the form of an introduction to the more specialized and detailed surveys now being carried out by the New Zealand Forest Service.

LOCALITY

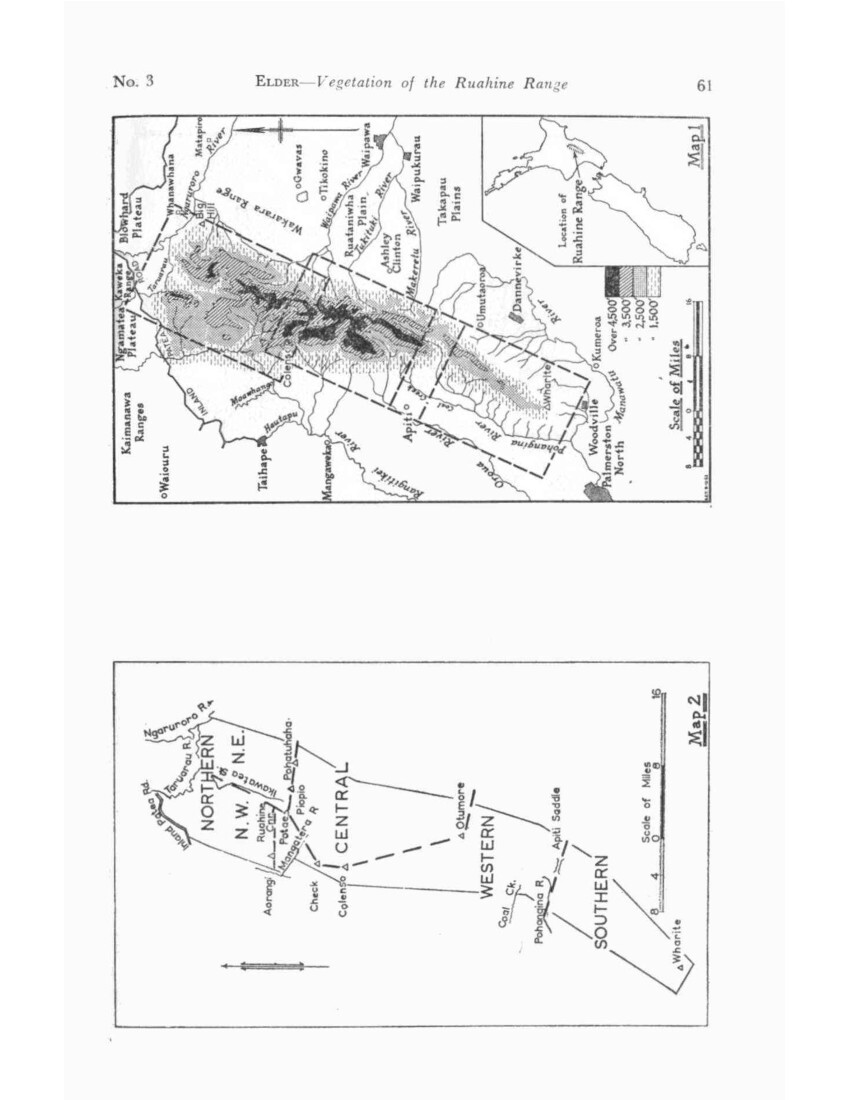

THE Ruahine Range is that portion of the main North Island fold mountains which lies between the Manawatu and Taruarau-Ngaruroro gorge systems. These separate it from the Tararua Range to the south and the Kaweka Range to the north. (Map 1.)

The Ruahine Range extends 56 miles in a NNE direction from the Manawatu Gorge, and is comparatively narrow, the southern third having an average width of little more than five miles, then widening to a maximum of some 15 miles towards the northern end. There are few foothills, and on the eastern side the divide forms a high continuous scarp above the plains of Hawke’s Bay, but there are a number of high subsidiary ranges diverging from the divide on the western side.

On either side farmlands extend to the foot of the main slopes, and at the southern end farmlands separate the range from the Manawatu Gorge itself. The induced scrubland of the Taruarau Gap intervenes between the Ruahine and Kaweka Ranges.

STRUCTURE

It is thus a high (5,678ft max.) continuous narrow range cut off from the rest of the mountain system. Its eastern boundary is formed by the Hawke’s Bay fault system, its western by the echeloned valleys of the Rangitikei, Oroua, and Pohangina Rivers and its northern and southern boundaries by the traverse gorges already mentioned.

Published by the Royal Society of New Zealand, c/o Victoria University of Wellington, P.O. Box 196, Wellington.

14 Transactions – BOTANY Vol. 3.

In profile as seen from the eastern side the range rises in notably smooth and even slopes from the gorges at either extremity up to an altitude of 4,000 – 4,500ft above sea level. The outline then becomes broken, but its peaks continue this gradient until the central block of the range is reached when there is a well marked step up of 500 feet or so. All points approaching or exceeding 5,500ft lie in this central block.

From the western side the profile does not show such distinct features. From the central block several high subsidiary ranges diverge in a NNW direction and hide most of the main divide. South of this divide between the Pohangina and Manawatu Rivers swings east and falls away to a scrubby ridge which is completely hidden from the west by two echeloned side ranges with a southerly trend. South of these again the divide rises to the oblong block of the Southern Ruahine Range.

The structure of the northern end of the Ruahine Range is more complicated. The greywacke axis terminates in a plateau overlooking the Taruarau Gorge and is about the only coherent geological features here in a crazy pavement of faulted blocks; the actual divide lies across the Pohokura basin from this, at first following the limestone scarp of the Mangaohane plateau, then continuing along a greywacke outlier, the OtupaeRange, to abut on the Ngamatea plateau which separates the Rangitikei and Ngaruroro catchments.

As described by Kingma (1959) the range has been elevated in recent geological times with Tertiary limestones occurring intermittently across its northern end and capping spurs in the Makaroro valley. It is probably moving as a series of transcurrent faults southward relatively to the Kaweka and Kaimanawa Ranges, leaving the Taruarau Gap and on a lesser scale the Pohokura basin and Colenso’s Lake as collapsed blocks, the latter two of especially stratigraphic interest as preserving the sequence of the original Tertiary deposits.

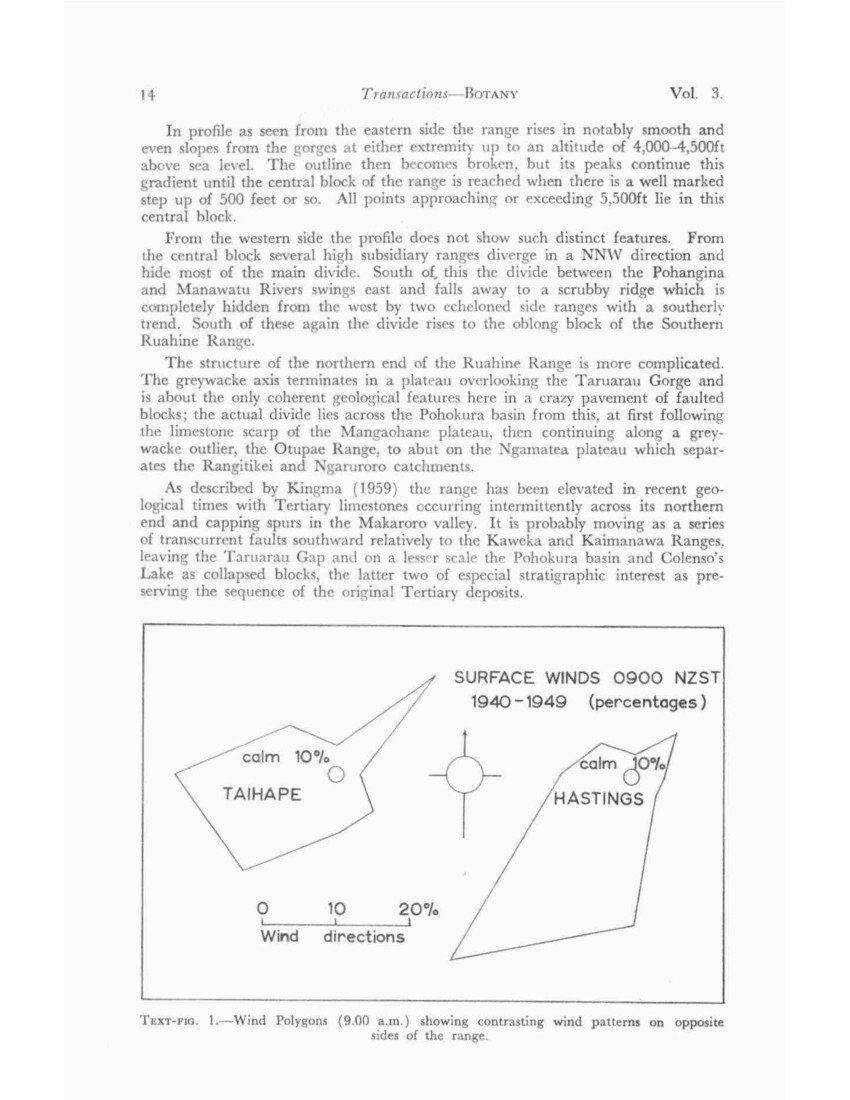

SURFACE WINDS 0900 NZST 1940-1949 (percentages)

calm 10% TAIHAPE

calm 10% HASTINGS

Wind directions

TEXT-FIG. 1. – Wind Polygons (9.00 a.m.) showing contrasting wind patterns on opposite sides of the range.

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 15

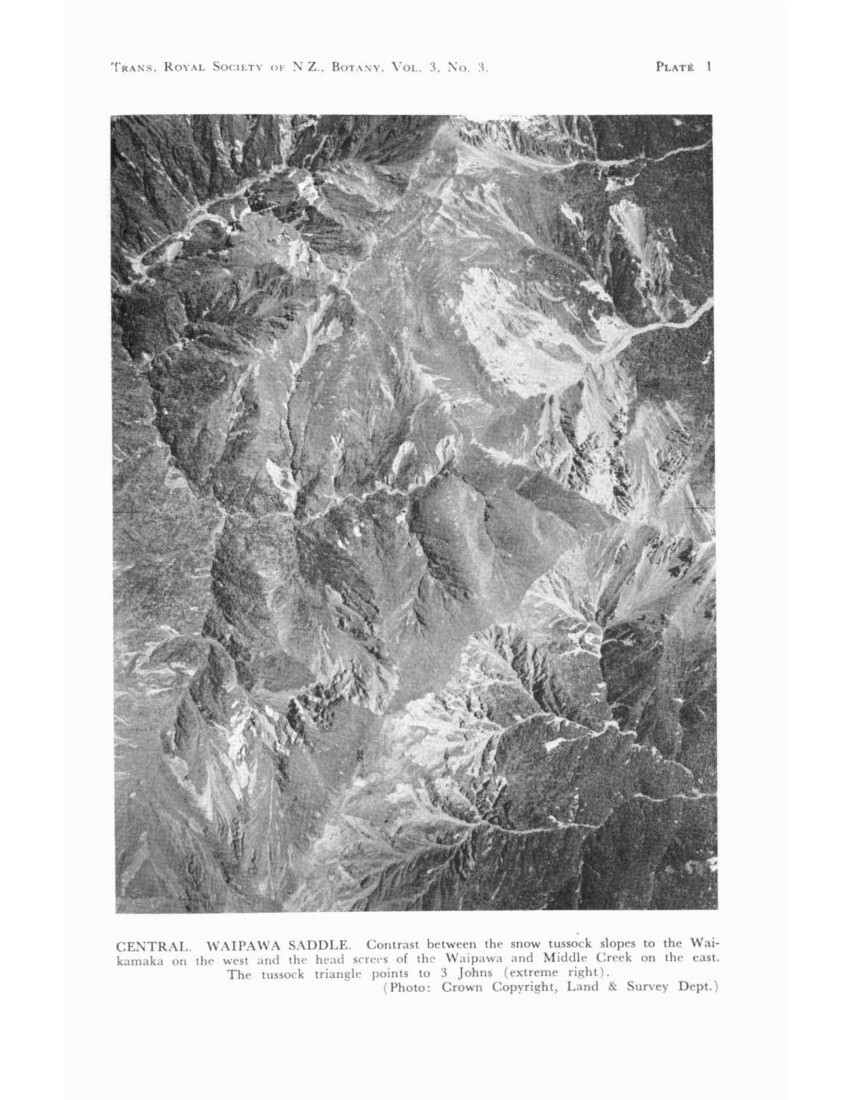

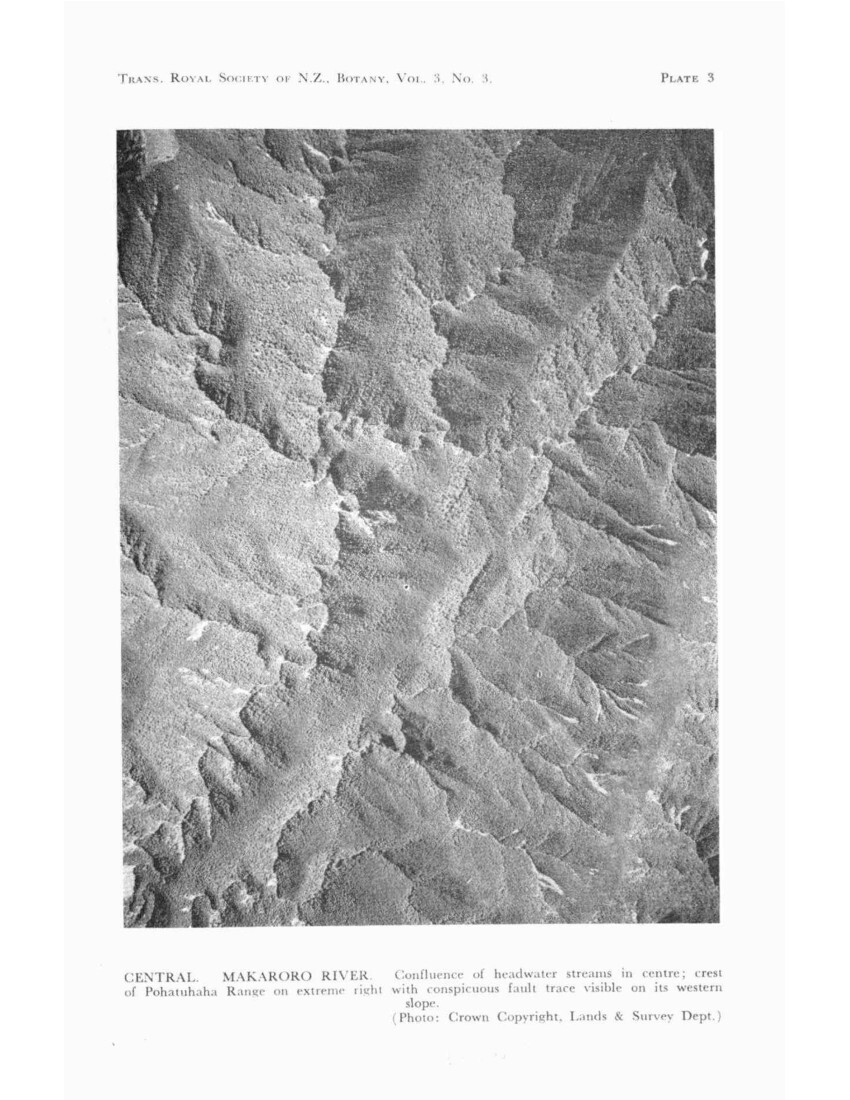

Although steep slopes and extensive screes are characteristic of the eastern face of the range, where they may be assumed to be mainly tectonic in origin (Plate 1), as well as several of the inner valleys of the central block, wide rolling crests and plateaux are characteristic particularly on the western wide. The sculpture of the Ruahine comes between that of the Kaimanawa and that of the Tararua, being further advanced than the former but not carried as far as the latter.

VOLCANIC ASH

Deposits of volcanic ash are negligible in amount except for remnant pumice hummocks of up to 3ft in depth on the lower part of the NE plateau, apparently an accumulation of wind drift. Two deposits can be distinguished in peat on the NE and Mokai Patea plateaus and as far south as Whanahuia. The most recent shower here is 3in thick, but beyond this both decrease sharply in thickness. Below the Waimihia ash, to the full depth of the peat on the No Man’s bog, are six or seven narrow separate ash bands, but there is no indication of a massive “Tongariro” shower.

CLIMATE

In general terms over 40% of the winds in the central areas of New Zealand have a westerly component, and over 20% come from between south and east; but these directions are considerably modified by topography, so that the differences on either side of the Ruahine Range are considerable. (Text-fig. 1.)

Nor’westerlies and westerlies in the South Taranaki Bight converge into the wind funnel of Cook Strait, with a change of direction tending to follow the coastline. Inland of this, towards the barrier of the Ruahine Range westerly-wind velocities appear to drop, and only occasionally do these winds cross the range with the development of a characteristic Fohn arch. The Manawatu Gorge, however, forms a minor wind funnel for westerly winds, bringing a high proportion of cloud to the lower slopes north and south of it.

On the Hawke’s Bay side of the range sou’westerlies and southerlies supply most of the cloud and most of the rain days, though the heaviest falls are brought by the comparatively infrequent winds between NE and SE.

The Taruarau Gap appears to have no effect on wind patterns, unless perhaps it contributes to the anomalous NE component of the Taihape wind polygon.

RAIN. Except for some gauges that the Hawke’s Bay Catchment Board have recently installed on or near the divide, rainfall is measured on the margins of the range only. The distribution of rainfall in the Ruahine Range is therefore at present not known.

Figures are low at the northern end, Mangaohane averaging below 40in though it is at an altitude of 2,750ft, and Whanawhana, opposite it at the eastern end of the Taruarau gap, just over 40in. (North of this, however, at Kuripapango, the rainfall approaches 60in in the lee of the Kaweka Range.) A slight increase appears to occur towards the south, reaching 50in at Rangiwahia on one side of the range and the same at Blackburn on the other. There is then a considerable increase, Table Flat, where the Oroua leaves the range, having 75in, and a new station (1,670ft) behind Ashley Clinton, probably over 90in, while south of this again Umutaoroa has 100in. No information is yet available from a gauge established on the divide (4,353ft) at the head of the Waipawa River.

16 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

SNOW. The heaviest snowfalls appear to visit the western side of the range. Colenso mentions snow damage on one of his early journeys, but damage to forest from this cause is not typical. The series of heavy snowfalls of the winter of 1961 were quite exceptional. They lay for a period and one particularly heavy fall, probably early in August, did considerable damage, particularly in red beech forest.

CLOUD. Cloud levels have been observed (9 a.m., 4 p.m.) from Havelock North along most of the eastern side of the range over a period of three years, July 1938 to August 1941, and over 13 months of this period observations from Kumeroa of the southern part of the range were also taken, together with a short check period of a month from Dannevirke.

The preponderance in Hawke’s Bay of winds with a southerly component has an effect on the cloud cover in the northern half of the range. From observations made from Havelock North the peaks at the head of the Oroua River, where the highest part of the divide begins, 25% of the days were reckoned to be substantially sunny. On the same basis this increased to 30% at the northern end of the range, while further north again in the Kaweka Range it reached 34%, the greatest value observed.

The southern half of the range is lower and the weather is increasingly dominated by a westerly component as the gap of the Manawatu Gorge is approached, with a considerable decrease in sunny days and increase of low cloud, and with these a marked change in the vegetation. The transition is difficult to observe from the Hawke’s Bay Plains, as the higher Ngamoko Range to the west of the divide shields it from the westerly winds but is largely concealed by it. South of the Pohangina Gorge, however, low cloud is characteristic of the Southern Ruahine, averaging 67% on Maharahara at about its centre and even higher on Wharite, the southernmost peak, both averaging only some 11% of sunny days over a 13-month period.

No comparable information is available for the western side of the range, but from sporadic observation cloud or fog frequently forms or lies along the western slopes when the rest of the range is clear. The different composition of the higher forest on these outer faces suggests that diminished sunshine is a factor.

TEMPERATURE. Both summer (63° F.) and winter (46° F.) isotherms run N-S along the general line of the range, the Hawke’s Bay side being warmer in summer and cooler in winter than the western side.

HISTORY

The Ruahines, like other ranges, were visited by the Maoris when hunting for birds (the skeleton of a lost hunter was noted by Colenso near Puketaramea) and as refugees (several traditional sites are recorded in the headwaters of the Mangatera); a number of traditional high-country routes are on record. As the Ruahines are a comparatively long narrow range, cross-country routes to and from Hawke’s Bay and the Inland Patea were of particular importance (the Te Atua Mahuru route, Te Parapara, being used by a war party as late as 1828), and there were also routes, less certainly known today, between southern Hawke’s Bay and the lower Rangitikei. In addition traditional routes ran north and south along the open crests in the northern part of the range. The more exposed routes could obviously be used only in favourable weather for lack of suitable clothing, and groups of tarns, which are a certain source of water even in periods of prolonged dry weather,

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 17

have traditional names. It has been suggested that muttonbirds, which were formerly known to nest above the bush line in considerable numbers, would have afforded a seasonal food supply of considerable value to parties making high-level traverses. The main effect on the vegetation of the use of the high country by Maoris lies in their use of fire for hunting or track marking, and several extensive areas of old fires suggest such fires that had got out of control. However, by no means all Maori routes took advantage of the open snowgrass tops; the best known (Te Parapara) followed valleys on either side, reducing travel above the bush line to a minimum. Colenso records the tradition of the destruction of a war-party here on a snow slide coming off Te Atua Mahuru.

This route is of particular botanical interest, as Colenso ascended it in 1845, making the first collection for the whole of New Zealand of a large number of high-country species. The listing of type localities in Allan’s Flora Vol. I (1961) gives at least 80 species and accepted varieties, exclusive of monocotyledons for the Ruahine Range and its neighbourhood.

Since Colenso’s time a certain amount of sporadic botanical collection appears to have been done along the flanks of the range, but it is not until after 1900 that there is any further record of extensive journeys, the most important being that of F. Hutchinson and B. C. Aston retracing Colenso’s route in 1911.

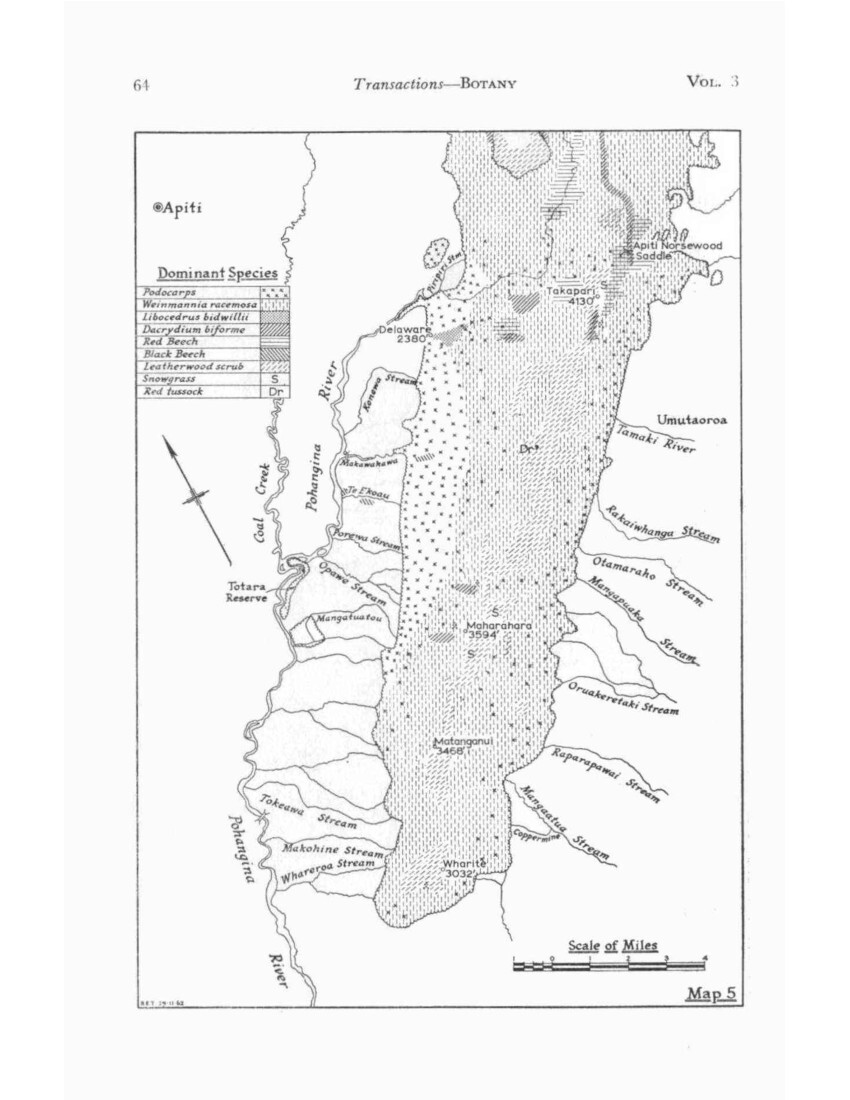

A more methodical botanical exploration of the range began in 1933 and, as a result of this, comprehensive vegetation maps were drafted by Druce in 1946, summarizing the coverage that had been made up to the break caused by the war. In the last 10 years various surveys have been carried out by different branches of the Forest Service with the aid of aerial photographs. This paper is for the most part a summary of the earlier work and essentially an introduction to those more detailed surveys.

FAUNA

BIRDS. There is a rumour or tradition that huias survived in the NW Ruahine up to about 1907, and a story is on record (Phillipps) of a skin collected in the same area by Morgan Carkeek in 1894 which was recognised as that of a “mohoau” (Notornis). Wekas were last seen at Kereru about 1925 (L. Masters, pers. comm.).

The narrowness of the range makes it a poor refuge, and visitors over at least the past 25 years have been repeatedly struck by the apparent paucity of bird life. The restriction of seasonal movement with the general replacement of flanking podocarp-hardwood forest by grassland is probably a sufficient cause. The winter migration of tuis to the eucalypts of the Heretaunga plains has been regular for at least the last 30 years, and recently bellbirds and, more surprisingly, pigeons and kakas have wintered in Havelock North, 30 miles or more from the nearest extensive forest. Some introduced birds are widely distributed throughout the range, the blackbird and the chaffinch being the most conspicuous; others are mainly marginal, the Australian magpie, for example, being strictly confined to grassland. Chaffinches have been noted flocking on occasion, but otherwise the paucity of bird life extends to introduced species.

This apparent scarcity of bird life needs confirmation. Some assessments are being made in the course of forest surveys (Ellis). If true it must be expected to have a bearing on insect control and on seed distribution and/or consumption. The only evidence of this nature comes from the Pohangina valley, where local

18 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

residents reported heavy defoliation of kowhai along the river flats by pigeons. The most likely reason for this is that competition from opossums in the adjacent Southern Ruahine had forced the pigeons on to alternative winter browse. The heavy flowering of kowhai in the Pohangina since that report suggests that the pressure has since eased, the opossum population being lower since the peak and collapse of mid 1955.

MAMMALS. The comparatively accessible tussock country of the northern and western Ruahines was stocked in the 1880’s, in the first place with merino sheep, and this was accompanied by more or less intense tussock burning. The NE plateau and the Otupae Range have been abandoned, apart from strays, for 20 years or more, but stock, mainly cattle, are still run on Mangaohane and the Mokai Patea, while the Pohokura basin has recently (1956) been disced and sown down in grass.

Towards the southern end of the range the practice of wintering cattle in the bush has not entirely died out, and names such as “The Cow Saddle” recall a former Te Ohu Station mustering route across the divide.

When the present survey began in 1932 the effect of red deer was inconspicuous except in the NE comer of the range, while opossums and goats were practically absent. As the survey proceeded, information about the animals, their spread and, later, measures for their control, together with observations on their effects on the vegetation became an integral part of what had begun as a botanical survey. It forms, however, an unwieldy component of the paper in its present form and for neatness’ sake has been treated separately (Appendix 1).

FIRE

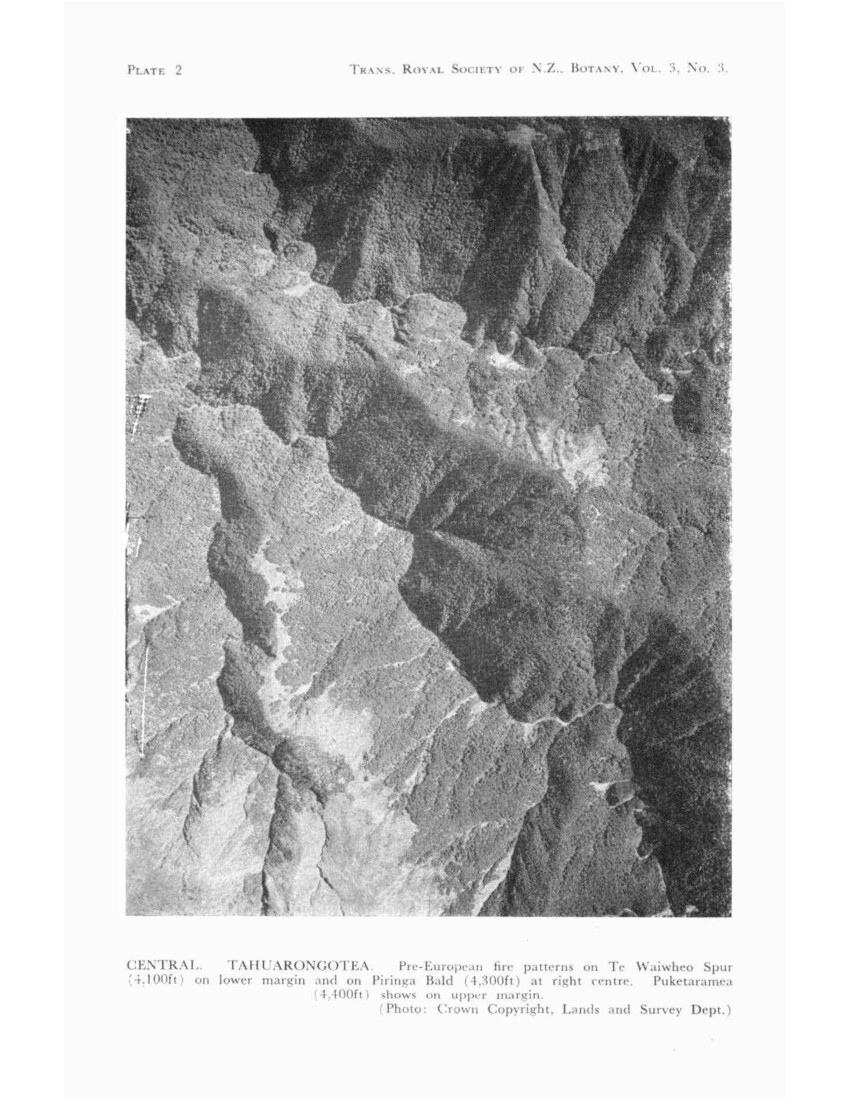

There is some evidence of pre-European fires at three points in the north and west of the range. On the Mokai Patea plateau the name Tahu-a-Rongotea (now given in the shortened form, Rongotea, to its culminating point) refers to fire. Early maps show that it was given to an area about half way down the plateau; and the irregular and unusual timber line on the eastern slope, together with, across the valley, an anomalous scrub face bearing a Maori name, Otukota, is supporting evidence of fire (Plate 2). Unfortunately there is no legendary information from which an approximate date might be estimated, but the recent discovery of buried charcoal, resembling deposits that are being studied in Canterbury, indicates that it occurred in the early stages of Maori occupation of the country (Wardle, pers. comm.).

A fire pattern extending from the margin of the Mangaohane tussock down the Otorere tributary of the Mangatera could well be thought, from a distant view, to be a consequence of European burning; but from the size of the regeneration dominants (Phyllocladus) this must be reckoned to be of considerable age.

The Pohokura basin may be considered a third area affected by pre-European fire as it is first recorded as occupied by tall kanuka (Leptospermum ericoides) scrub, a highly unlikely climax in a low-lying sheltered limestone basin with occasional pockets of matai (Podocarpus spicatus) forest.

The Inland Patea tussock was occupied at an early stage of European settlement, and a good deal of the isolated Otupae Range carries young beech (Nothofagus) forest which has partly regenerated after burning of that date. Although evidence of tussock burning is general it should be put on record that at one period Mangaohane policy was against burning (Morrin).

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 19

On the eastern side of the range the original Seventy-mile Bush, the belt of podocarp-dominant forest that ran between the foot of the range and the tussock-covered Takapau and Ruataniwha Plains from the head of the .Manawatu River to Kereru has been almost entirely replaced by grassland, its outline being roughly preserved by the scattered totara (Podocarpus totara, see Appendix 2) of bushy form which appears to have been able to regenerate m grassland m the face of browsing.

Fires have here and there run up the face of the range, and in some instances have been more extensive. In 1910 a fire ran up the Makaroro valley for several miles as far as the start of Colenso’s Track, and in 1939 fire in cut-over bush adjacent to this in the Makaroro mill workings has left an area of several hundred acres partly in grassland, partly in dense wineberry (Aristotelia serrata) thickets which are still persisting.

There are traces of fire on both sides of the northern head of the Waipawa River, and if even-aged regeneration of mountain beech (Nothofagus solandri var. cliffortioides) on old screes in the basin is connected with this, as seems likely, an extensive fire occurred here prior to 1903.

Two major fires have occurred near the head of the Tukituki, the first, some time in the 1880’s, spreading from either Howlett’s Hut or the head of the Moorcock Stream, across the range into the head of the Oroua and further south across the Pohangina Saddle and into the head of the Makeretu River, an area of some 5,000 to 6,000 acres. The name Daphne Ridge is said to come from the abundance of Pimelea buxifolia in the scrub-tussock succession that followed the burn

During the drought of 1946 a fire starting in the Pohangina Hut ran over part of this area, reaching the divide just south of Otumore, but mainly travelling back into the head of the Moorcock valley.

In the Southern Ruahine there are traces of fire on the lower forest margins and up some of the outer spurs, characteristically indicated by dense stands of Cyathea medullaris, the large black tree fem, but none of these is extensive. One fire, however, in 1915 ran up the Pohangina Gorge from the west, crossed the range at the Apiti-Norsewood saddle, and went on to Te Ohu Station. My information comes from L. H. Bowden, who stresses that this was a series of spot fires and that the bush in between was untouched. Today a few anomalous patches of Coprosma/Myrsine scrub in the forest near this saddle presumably mark the sites of these spot fires.

An extensive fire which is stated to have run southwards along the western margin of the Southern Ruahine about 1927 appears to have been confined to farm land and to have had little effect on the main forest.

VEGETATION

TAXONOMY. For so comparatively limited an area the Ruahine Range has become the type locality of an exceptional number of high-country plants, thanks to Colenso’s early missionary visits to the Inland Patea. The regular listing of type specimens and localities in the 1961 Flora is, because of this, of particular assistance to work in the Ruahine Range. In addition, the provision of footnotes explaining the history of the nomenclature and the status of the various synonyms and partial synonyms which have bedevilled taxonomists in the past is most welcome, as so many of these originated with Colenso’s collections in his later

20 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

years in the remnants of the Forty-mile Bush around Dannevirke. Some of these can usefully be distinguished as true-breeding forms when one is working on a local scale. Names that are in popular use for certain widespread or characteristic species are used in the text. Their formal equivalents are listed in Appendix 2.

SPORADIC DISTRIBUTION. The Flora records geographical distribution in general terms. Consequently a number of species, such as those occurring on the volcanic plateau and again in NW Nelson, are given a range which includes the Ruahine, though they have not in fact been observed there. Others are known only from one small colony, as that of semi-juvenile Pittosporum turneri (Mangaohane forest margin), or even from solitary plants, as P. colensoi (Oroua) and Phymatodes novae-zelandiae (Pohangina) at considerable distances beyond their previously known distribution. There are probably others, but none of these is likely to prove of any significance in their communities. This sporadic occurrence applies to two species for which the Ruahine Range is the type locality, Lycopodium novae zelandicum and Nothofagus truncata, neither of which has been recorded in field surveys in the past 30 years; in fact there is a gap in the known occurrence of the Nothofagus at the present day of 100 miles or more along the East Coast. Ascarina lucida may be mentioned here. Its pollen has been recognized in a Western Ruahine bog though the living plant has not been recorded.

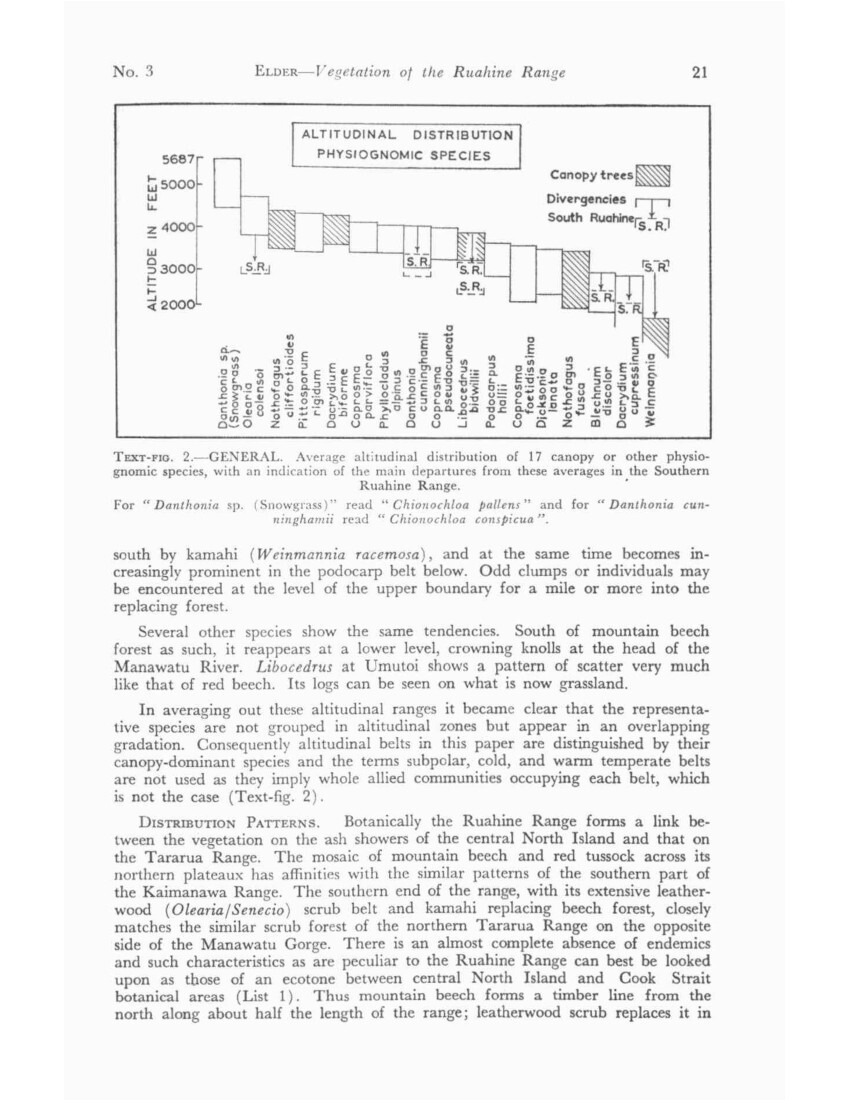

ALTITUDINAL BELTS. The most striking feature of high-country vegetation is its stratification into well marked altitudinal belts, and the examination of these is the most obvious line for investigation of distribution. These belts were used as the basis of an earlier survey of the Tararua Range, but there was a suspicion there that there had been a tendency to lump groups of species into belts on rather too arbitrary a basis. Therefore from the commencement of work in the Ruahine care has been taken to check on this tendency by establishing a network of corrected spot heights and noting the altitude at which different species occur. Frequencies also have been recorded on a scale which, though necessarily approximate, is as consistent as it can be made on a personal estimate. Field experience with Forest Service survey plots has afforded a valuable check on the accuracy, within limitations, of such estimates.

Analysis of these records for a selection of the more important species shows, of course, variations recognizably due to exposure, aspect, and presumably in some instances to soils, but these average out to give mean altitudinal ranges which can be accepted with confidence. Upper limits are very sharp and in practice it is fairly easy to select a line above which any given species ceases to be a recognizable component of its community; occasional individuals which may occur above this are most commonly limited to a vertical interval of the order of as little as 200ft.

The corresponding lower limit is usually less sharply defined and the sporadic scatter of individuals of a species to lower altitudes is wider. However, sufficient information is available to indicate that the vertical range of nearly all the main species examined (that is to say, the range within which they can be classed as a definite component of their community) is with quite striking constancy, between 900 and 1,200ft.

Red beech (Nothofagus fusca), on first calculation, was the chief exception, with some wide downward fluctuations below a fairly regular upper boundary. A re-examination of observations showed that these were associated with the absence of red beech from both ends of the range. In either case as it approaches its limit it is increasingly replaced, in the north by mountain beech and in the

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 21

south by kamahi (Weinmannia racemosa), and at the same time becomes increasingly prominent in the podocarp belt below. Odd clumps or individuals may be encountered at the level of the upper boundary for a mile or more into the replacing forest.

Several other species show the same tendencies. South of mountain beech forest as such, it reappears at a lower level, crowning knolls at the head of the Manawatu River. Libocedrus at Umutoi shows a pattern of scatter very much like that of red beech. Its logs can be seen on what is now grassland.

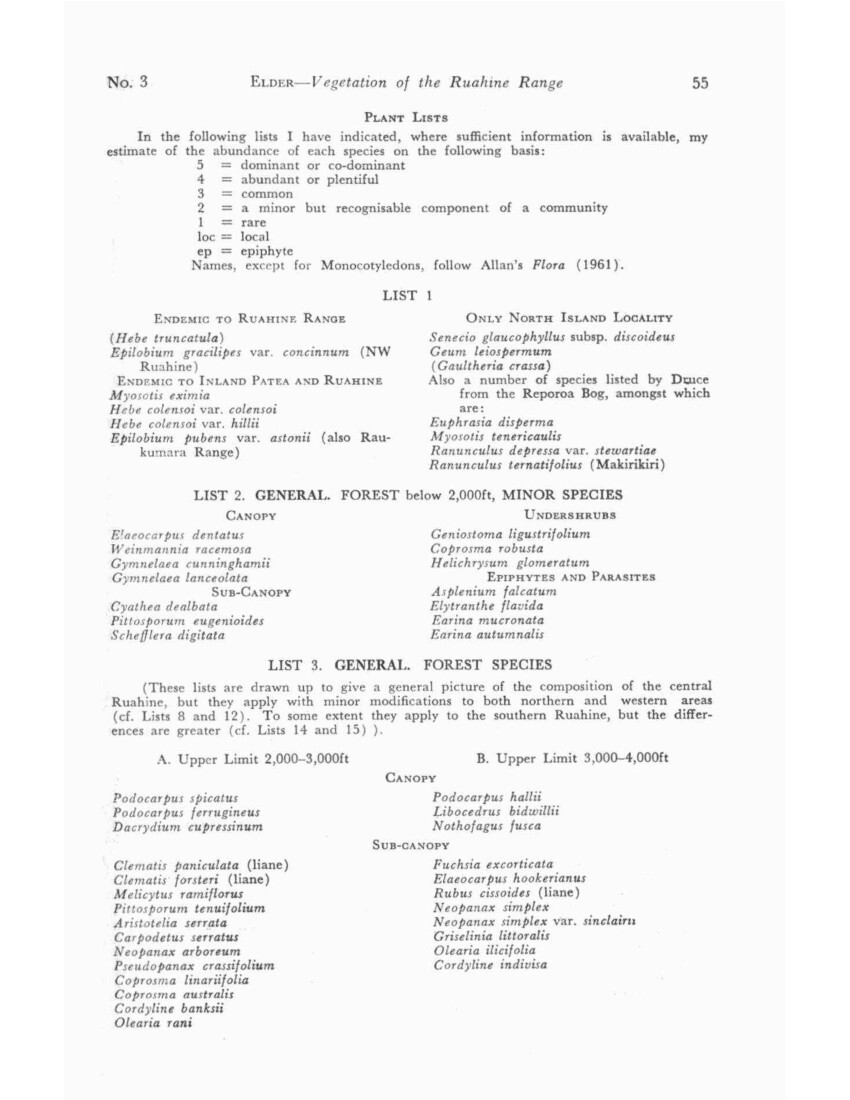

In averaging out these altitudinal ranges it became clear that the representative species are not grouped in altitudinal zones but appear in an overlapping gradation. Consequently altitudinal belts in this paper are distinguished by their canopy-dominant species and the terms subpolar, cold, and warm temperate belts are not used as they imply whole allied communities occupying each belt, which is not the case (Text-fig. 2).

DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS. Botanically the Ruahine Range forms a link between the vegetation on the ash showers of the central North Island and that on the Tararua Range. The mosaic of mountain beech and red tussock across its northern plateaux has affinities with the similar patterns of the southern part of the Kaimanawa Range. The southern end of the range, with its extensive leatherwood (Olearia/Senecio) scrub belt and kamahi replacing beech forest, closely matches the similar scrub forest of the northern Tararua Range on the opposite side of the Manawatu Gorge. There is an almost complete absence of endemics and such characteristics as are peculiar to the Ruahine Range can best be looked upon as those of an ecotone between central North Island and Cook Strait botanical areas (List 1). Thus mountain beech forms a timber line from the north along about half the length of the range; leatherwood scrub replaces it in

Photo caption –

ALTITUDINAL DISTRIBUTIONPHYSIOGNOMIC SPECIES

TEXT-FIG. 2. – GENERAL. Average altitudinal distribution of 17 canopy or other physiognomic species, with an indication of the main departures from these average in the Southern Ruahine Range.

For “Danthonia sp. (Snowgrass): read “Chionochloa pallens” and for “Danthonia cunninghamii read “Chionochloa conspicua”.

22 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

the south and it overlaps it in the centre but is absent from the northern quarter of the range. Both are physiognomically important and with associated species enable natural areas to be distinguished in a north-south direction along the main backbone of the range.

There is also an east-west ecotone running from this main axis across the subsidiary ranges which run out on the western side. Mountain beech does not reach the western margin; its place is taken by cedar (Libocedrus) forest, an extension of the cedar forest which occurs in a broken pattern from the margin of the Waimarino Plain, round the western side of the volcanic plateau and across the south-western extremity of the Kaimanawa Ranges.

Thus the timber line, with or without a scrub line, shows several distinct patterns both from north to south and from east to west, and the presence or absence of red beech and kamahi at lower altitudes also shows patterns which correspond to some of these and together form a basis for a subdivision of the range into natural areas.

NATURAL AREAS (Map 2)

These may be listed in their simplest form as follows:

CENTRAL RUAHINE. Mountain beech dominant above 3,600ft, red beech below this.

NORTHERN RUAHINE. Mountain beech dominant or alternating with red tussock, red beech scarce.

WESTERN RUAHINE Cedar dominant above 3,600ft, red beech below.

SOUTHERN RUAHINE. Leatherwood dominant above 3,000ft, kamahi below this. Beeches absent.

The ecotone between Central and Southern Ruahine forms a belt about six miles wide which runs diagonally across the Ngamoko Range, and, though here included in the Western Ruahine, may be considered as a further subdivision. Though mountain beech is absent, it differs from the Western Ruahine in so far as Dacrydium biforme tends to replace cedar at the timber line and dominates it on the eastern side.

The Central Ruahine is considered first as the basic pattern of which the surrounding areas are variants.

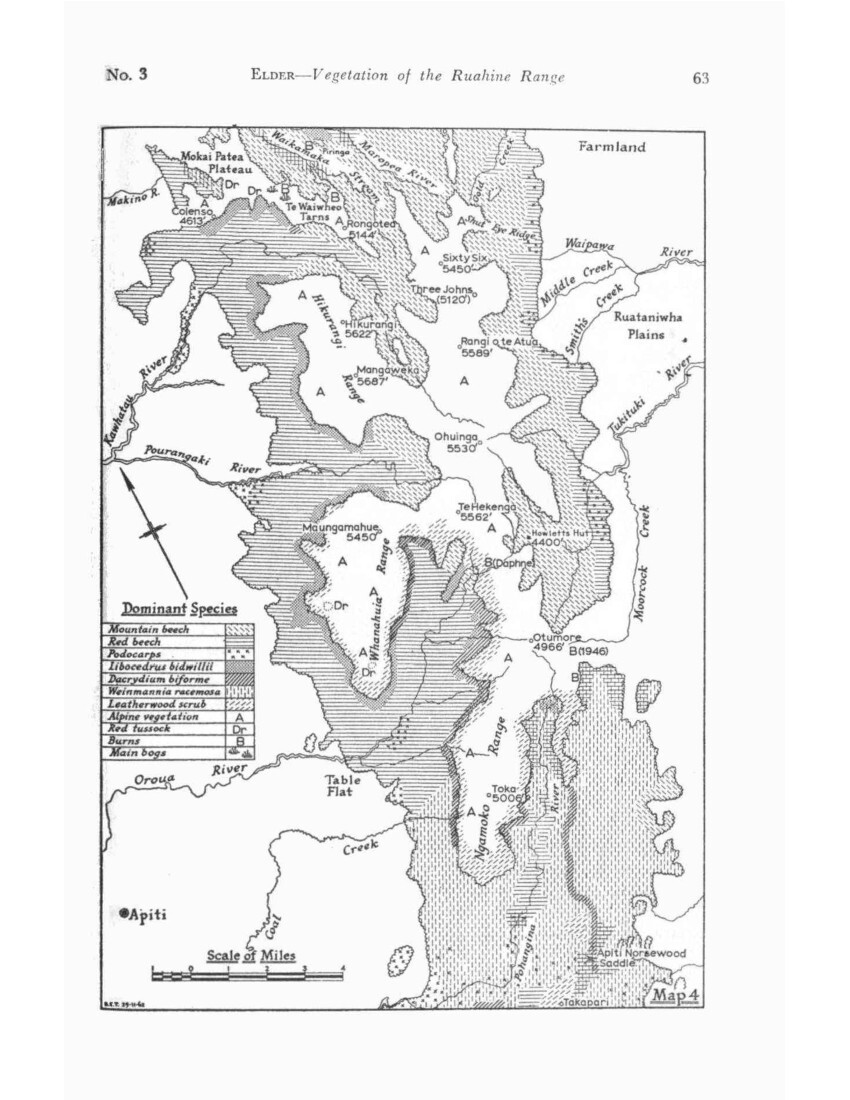

CENTRAL RUAHINE (Map 4)

On this basis the Central Ruahine includes all points on the divide exceeding 5,500ft and most of the diverging ranges to the west of it between the Mangatera and Pourangaki valleys, so that about a third of the area lies above the timber line and the only considerable areas of high country outside its boundaries are the Whanahuia and Ngamoko Ranges to the south, carrying a western type of vegetation.

The boundaries are on the whole fairly satisfactory. The northern boundary cuts off the plateau country which terminates at the head of the Makaroro valley; the southern boundary slanting across the Pourangaki and Oroua valleys marks fairly closely the replacement of mountain beech timber line by cedar. The western boundary also follows the change in timber line but is less satisfactory in that the

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 23

tussock and bog of the Mokai Patea would more conveniently be grouped with those of the Whanahuia Range, bringing out certain affinities between the western and northern subdivisions.

The eastern face of the range drops abruptly 3,000 to 3,500ft on to the plains of Central Hawke’s Bay, and contains only two longitudinal valleys of any size, the Makaroro and Tukituki, so that forest on this side occupies a fairly narrow belt along the face of the range; west of the divide larger forested areas occupy the Mangatera and Maropea basins. The upper portions of these as well as of the Kawhatau and Pourangaki valleys fall within the area of mountain beech forest.

CENTRAL: PODOCARP FOREST

In the course of European settlement, the whole of the Hawke’s Bay (eastern) side of the range has been cleared and grassed up to the foot of the main scarp, to an altitude, opposite the middle of the range, of about 2,000ft. Consequently only traces remain of lowland forest, the former belt of podocarp-maire (Gymnelaea spp.), the extension of the Forty-mile Bush known as the Seventy-mile Bush, which ran between the tussock of the Takapau and Ruataniwha Plans and the Ruahine Range to as far north as Kereru. From the few remaining pockets, of which Gwavas Bush is the largest and most important survivor, totara was an important constituent in places and the regeneration of totara in grassland which is now a feature of the rolling country from Ashley Clinton to Kereru appears to outline the area what was previously forested, although Podocarpus totara has not been seen within the boundary of the range in the vicinity. (List 2.)

At the present day a fringe of podocarps, mainly rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) with a little matai (Podocarpus spicatus) and kahikatea (P. dacrydioides) occur either scattered through the lower red-beech forest or in small pockets on favourable sites (List 3A). Scattered trees of miro (P. ferrugineus) are also present to somewhat higher altitudes, while thin-barked totara (Podocarpus hallii) is rather a component of red-beech forest, whose altitudinal range it matches, than of podocarp forest proper. Logging in these remnants at the northern (Makaroro) and southern (Moorcock) margins has only ceased in the past few years.

In the heart of the range at Colenso’s Lake (2,300ft) which lies on a down-faulted tertiary block in the upper Mangatera valley, podocarps occur in red-beech-dominant forest together with a number of characteristically lowland species. The abundance of matai and relative scarcity of rimu relate this community to the matai-dominant podocarp remnants in the Northern Ruahine. Although totara has been reported from Colenso’s Lake this appears likely to have been a misidentification as only the related Podocarpus hallii could be found on a recent visit.

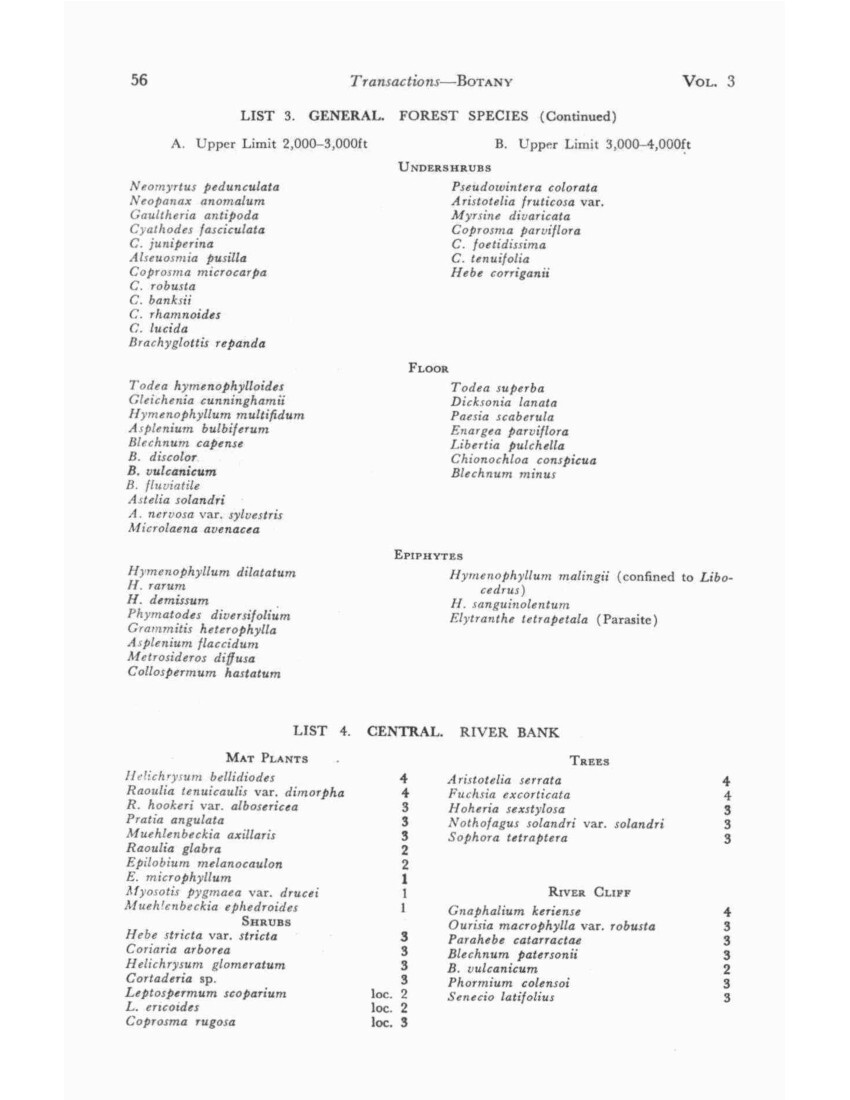

CENTRAL: RIVER BANK

The streams in the larger valleys, particularly those draining the eastern side of the range, are unstable at the present ay with frequent changes of channel and much deposition of shingle and scouring out of older terraces, which suggest at least one previous cycle of activity. An occasional local cloudburst, as that of the winter of 1954 in the Makaroro-Waipawa area, brings about major changes which will be recognizable over a long period.

24 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

A succession of specialized plants (List 4) colonizes the bare shingle, beginning with mat plants, continuing with shrubs and certain trees, the more stable terraces eventually being occupied by the neighbouring forest species. Some species which may not be found in the main forest, such as kowhai (Sophora tetraptera) and kamahi, commonly occur on the hill slopes immediately above the terraces, probably favoured by the increased light that reaches them there. A sprinkling of high-altitude species that have come down stream is characteristic.

River cliffs, both dry and wet, also support characteristic communities, including at the resent day a number of plants that are palatable to browsing animals and which have almost disappeared from accessible sites.

A few species in these categories but otherwise confined to the Northern Ruahine extend into the central area, the Central North Island form of Hebe parviflora var. arborea on river terraces in the Makaroro on cliffs Carmichaelia odorata var. pilosa in one of the Makaroro tributaries, and Angelica rosaefolia in the Makaroro, Maropea, and Mangatera valleys.

CENTRAL: RED BEECH FOREST (List 3)

From 2,000ft upwards red beech is the usual dominant and above the limit of rimu (c. 2,800ft) it is the sole canopy dominant up to 3,600ft, higher in sheltered basins and on deeper soils, lower on exposed ridges. Closely associated with it is Podocarpus hallii with an almost identical altitudinal range, but usually, in this type of forest, as a sub-canopy species. As has been noted in describing podocarp forest, miro overlaps into red-beech forest as a minor component. A fair amount of light filters through the canopy and over wide areas one or other of two species of fern, Dicksonia lanata or Blechnum discolor forms a dense waisthigh floor cover. Few shrubs can compete with this cover and seedlings beneath it are infrequent: Neither fern appears to show any site preference over the other and it is exceptional for either to show any trace of browsing. The Dicksonia, until the new Flora appeared, was listed as of infrequent occurrence- “somewhat scarce and local in the North Island” (Dobbie, 1951). Its abundance at the [the] present day over wide areas in several of the central ranges may be a recent development and the opening of the floor by deer a possible factor.

North-facing slopes on which scattered large red beech form a discontinuous canopy with no replacement in sight (pole, sapling, or seedling) and with a dense fern cover beneath them are frequent in the Ruahine, as in the northern part of the Kaweka Range. As neither fern species flourishes under full exposure to light the further opening of the canopy may be expected to give rise to major changes, but it is not yet clear what these will be.

Towards the northern boundary of the area – that is to say, approaching the belt of country across the Inland Patea where red beech occurs sporadically or is absent from wide areas, it tends to persist at low altitudes but is increasingly replaced by mountain beech above 3,000ft. In several localities where it persists at ca. 3,600ft a canopy of stag-headed red beech with mountain-beech saplings and seedlings beneath indicates a process of replacement.

Towards the southern boundary sub-canopy kamahi is an increasingly important component of red-beech forest, becoming co-dominant beyond this and replacing it in the Southern Ruahine.

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 25

Some islands of mountain-beech forest below 3,000ft are conspicuous in aerial photographs, chiefly between the Makaroro and Waipawa Rivers. Their dense canopy suggests even-aged fire patterns, but investigation has shown no trace of fire, and in one of them at least on the Shut Eye Ridge not only is the mountain beech all-aged, up to 125 years old, but several large red beech, up to 40in in diameter, are scattered through with their trunks shorn off below canopy level and their crowns merging with and indistinguishable from it. These islands occur on knobs and ridges, the even canopy is a wind roof and the pattern probably originated from a destructive gale more than 120 years ago.

One feature in red-beech forest on steep valley faces has been the increase in the number of slip faces, first apparent about 1940 in the Waipawa and Makaroro, where their development has been most closely followed. The increase can fairly certainly be attributed to deer, which reached their peak in this area about 1935. Slips frequently started where deer had congregated on sunny slopes, their trampling destroying the moss and root cover, after which the exposed rock began to disintegrate. Recent observation (1962) shows the beginning of revegetation on several of these in the Waipawa, and fresh rock falls only on a minor scale; intensive hunting had then been carried on for three years in this valley and seems to be the major reason for this recovery.

In the Makaroro one large scree blocked the river about 1957 and formed a lake which persisted for two or three years; a similar dam across the Maropea River was encountered in 1941.

In the Makaroro deer damage is only part of the story. The valley sides are steep and present a series of comparatively stable faces or bluffs with unstable rubble faces between them. The fire of 1910 swept these slopes in the lower part of the valley and today second-growth scrub forest with a good deal of exposed rock is common below Colenso’s Track. Upstream of this, however, although red beech is dominant, with exceptionally vigorous regeneration on stable slopes, the rubble slopes are usually occupied by Pittosporum eugenioides, Melicytus ramiflorus, or Aristotelia serrata, the latter sometimes in pure stands. The floor commonly consists of loose boulders or rubble and large beech logs are frequent. Clumps of pole red beech occur sporadically, but otherwise over most of these faces the absence of beech regeneration is marked. The pattern does not suggest fire and no trace of charring has been found in the upper part of the valley.

However, some catastrophic event seems to have been responsible, and the abundant evidence of recent faulting in the Makaroro headwaters, some of which is conspicuous in aerial photographs, suggested that a major earthquake within the last 200-300 years was a likely cause.

The most conspicuous and apparently most recent fault trace which shows up as a narrow furrow in the canopy a mile or more in length along the western slope of the Pohatuhaha Range, was examined with this possibility in mind, but the presence of large cedar, reckoned to be 400-500 years old, growing in the actual fault trench, fails to bear this out (Plate 3).

CENTRAL: MOUNTAIN BEECH FOREST

Above red beech (c. 3,600ft) mountain beech is the dominant canopy species to the timber line, which has an average maximum altitude of 4,400ft, but its discontinuity is a conspicuous feature of the Ruahine Range, with tongues of

26 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

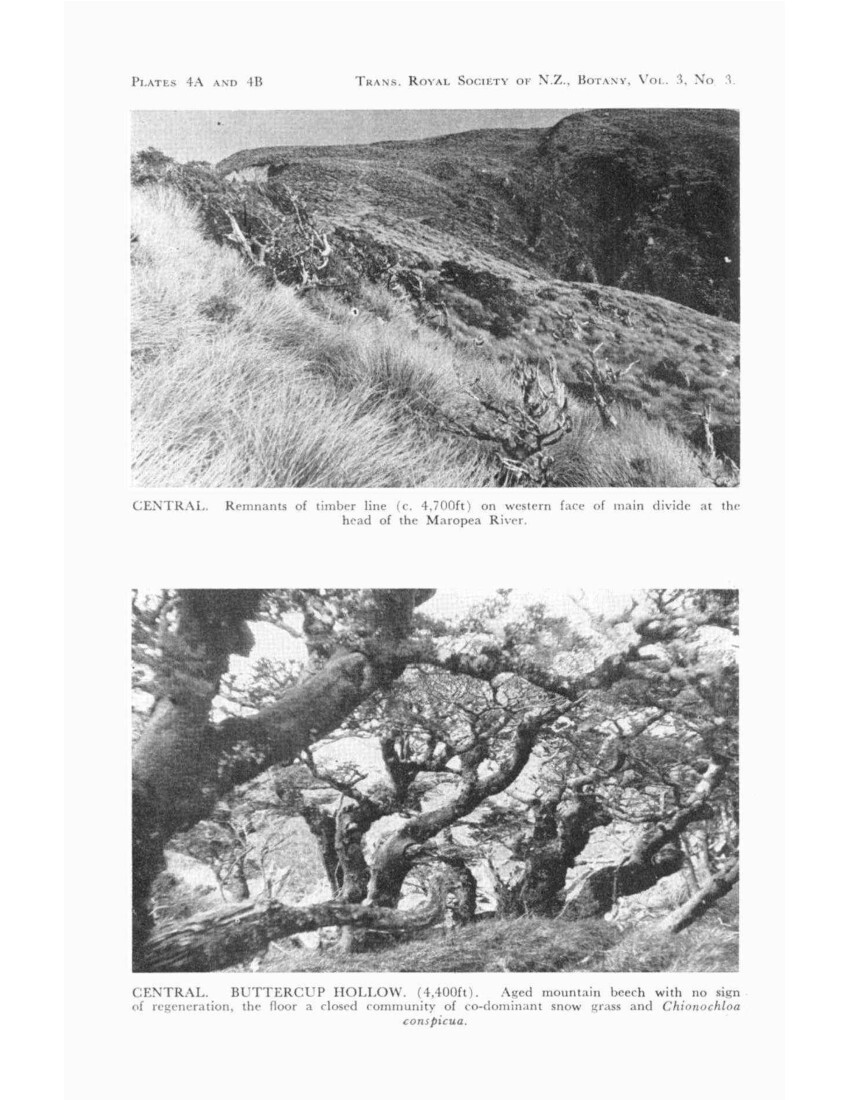

tussock and leatherwood breaking its outline, mainly down gullies which, however, show traces of a former tree canopy not only in fallen logs but also in dead standing trees whose branches may still outline a former wind roof. There is also similar widespread evidence of a former timber line some 200-300ft above the present one (Plate 4A). Ring counts of mountain beech in the Ruahine Range have not produced a figure of above 150 for the largest trees, and, on the assumption that few dead trees will remain standing for more than a further 50 years, this gives evidence of a considerable change having taken place over as recent a period as the last 200 years. (It must be noted that these ring counts were made in the field. Wardle (1963b, p. 35) gives consistently higher counts and considers (pers. comm.) that scanning by microscope is necessary for slow-growing timber.) Not only has there been a retreat in altitude, but the pattern of the slopes, with trees clustered on the drier ridges and knolls and regeneration confined to them, with leatherwood and tussock replacing them in gullies, suggests that conditions have become wetter.

A timber line community of old gnarled mountain beech over a closed tussock floor of Chionochloa conspicua ssp. cunninghamii and/or snowgrass is associated with level or slightly sloping ground and so has presumably some connection with drainage (Plate 4B). There is little sign of replacement of the canopy, which may be so open as to approach a park-like pattern of separate trees. This is described more fully in dealing with its occurrence in beech-cedar ecotones (p. 38).

A terrace above the Waikamaka valley at an altitude of 3,600-4,000ft (that is, towards the lower limit of mountain beech) though of small extent is of particular interest; for when first observed in 1940 it had the same pattern of dead trees standing in Chionochloa conspicua meadow, but has since changed with some rapidity. Aerial photographs taken in 1950 showed an unusual texture of scattered conical trees appearing, and by 1954 in addition to these the tussock had been largely replaced by dense scrub while most of the dead trees had fallen. The conical trees were found to be, rather unexpectedly, mountain beech some 12-15ft in height and 33-34 years of age, the scrub mainly species of Coprosma but with some leatherwood and tussock, the latter tending to dominate up the slope. A local fire dating prior to 1922 would seem to be the most likely origin of this pattern, but no trace of charring has been found.

In the snowgrass above the present timber line what appear to be scattered buses of mountain beech may occur among the logs of the former timber line, particularly along the divide above the head of the Maropea River, but still more so on lower ridges east of the divide, as for instance the Shut Eye ridge, which is particularly exposed to violent downdraughts and eddies in westerly gales. On examination these are often found to be the branches of prostrate trees whose trunks may be up to 20ft in length and a foot in diameter.

On the western and southern boundaries of the Central Ruahine area where mountain beech is replaced by cedar forest and scrub, several distinctive patterns occur which indicate the downward and outward movement of beech forest into the neighbouring formations. This is described in more detail at the end of the Western Ruahine section where the cedar-beech ecotones are discussed.

CENTRAL: CEDAR – DACRYDIUM BIFORME

Cedar, more or less associated with Dacrydium, occurs over most of the range m mountain-beech forest, most commonly at an altitude a little below 4,000ft, where its corneal heads frequently form a distinct belt. It is, however, almost impossible to find a sound tree, even apparently healthy and vigorous trees commonly having only an inch or so of sound timber, with close and even rings, surrounding a core of rotten wood. Seedlings or saplings are practically non-existent

NO. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 27

in the upper part of its range (see Text-fig. 2), but become more frequent lower down, and where cedar occurs below its usual range they may become common. One all-aged stand occupies a limited area on a scrubby shingle slope on the northern boundary towards the foot of Pohatuhaha (c. 3,300ft). Narrow spurs above the inner river valleys frequently carry a conspicuous line of cedars also descending below their usual range.

A pattern of scattered bushy Dacrydium biforme on the tussock spurs that rise above the beech timber line is frequently seen throughout the Central area.

CENTRAL: UPPER STREAM BANK

Mountain beech commonly colonizes river terraces and stream banks well below its usual range. In the lower part of the Waikamaka valley silver beech, extending from the adjacent Mokai Patea colonies (Western Ruahine), is common and may even be co-dominant with mountain beech.

A characteristic shrub of the upper river terraces near the timber line is Hebe truncatula, which is also a pioneer colonizer of screes and is described in that connection. Coprosma rugosa is abundant in many places, though less widespread, and Muehlenbeckia axillaris is a conspicuous mat plant of these higher reaches, where the proportion of subalpine plants of the same form increases with altitude.

CENTRAL: SUBALPINE

Except for the major volcanoes all the mountains of the North Island lie well within the range of vegetation, but a considerable proportion, exceeding 30%, of the area of the Central Ruahine lies above the timber line. Dissection has not gone as far as on the Tararua Range, so that there is a mixture of narrow ridges and wide rolling summits with a considerable proportion of bare rock and scree on their sides. Two closed communities cover much of the surface; leatherwood scrub dominated by Olearia colensoi below 4,700ft; and snowgrass tussock, which reaches the highest altitudes and covers considerable areas, particularly on the western side. Extensive peat bogs occupy the upper part of the Mokai Patea plateau, and similar smaller bogs occur north of Tupari and on the Hikurangi Range in the lee of the higher crests. There are also small boggy areas on ledges where snowdrifts accumulate; these are occupied by a distinct community of mat species. Screes in the initial stages of stabilization carry a sparse vegetation of specialized plants with extensive root systems.

CENTRAL: SUBALPINE SCRUB

Olearia colensoi and Senecio elaeagnifolius are present in and above the timber line throughout the Central Ruahine, but typical dense leatherwood scrub dominated by the former is only encountered in limited areas, mainly in basins or on the broader spurs below 4,700ft (List 7).

On the southern boundary, in the near absence of mountain beech, the steep south-facing slope into the Oroua River is occupied by a major scrub formation with a vertical range approaching 1,000ft. (This was the scene, in 1948, of the arduous Howlett’s search for a crashed RNZAF plane which had disintegrated in 10-foot leatherwood.) This adjoins the induced scrub-tussock association of the extensive Daphne Ridge burn of the 1880s, where the original pattern is obscured.

28 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

Over most of the Central Ruahine a characteristic scrub-tussock formation extends downwards into the numerous gaps in the timber line, Chionochloa conspicua replacing snowgrass below 4,500ft. Olearia colensoi has not been found on the Kaweka or Kaimanawa Ranges to the north and Senecio elaeagnifolius occurs only sporadically, so that leatherwood scrub as a formation is absent from a belt 40-50 miles wide. On the Ruahine Range the northernmost occurrences of Olearia lie on an oblique line from the lower end of the Mokai Patea plateau to the vicinity of Apias Creek on the NE plateau, thus roughly following the boundary between the western and central areas. The distinctive features of leatherwood along this boundary are described more fully in the western Ruahine section of this paper.

Though scrub as a formation ceases at about 4,700ft, Olearia colensoi persists as a sprawling shrub, often only a few inches high, to above 5,000ft, typically on south-facing slopes. Dracophyllum recurvum has a somewhat similar range and habit, but several woody shrubs, the chief of which are Senecio bidwillii, Hebe odora, and Hebe subsimilis, maintain an erect bushy form scattered through snowgrass tussock to above 5,500ft (List 5B).

A comparison of earlier species lists with more recent ones shows that considerable changes have taken place over the past 20-25 years in the composition of alpine scrub; some, once regularly listed as common and occasionally even as abundant, are now inconspicuous or recorded only on inaccessible sites. All are species favoured by deer, and the period covers the build-up of the deer population along the range. Neopanax colensoi has almost completely vanished; Aristotelia fruticosa (the Tararua variety) and Olearia arborescens have become infrequent, as has Gaultheria subcorymbosa south of the Waipawa Saddle. Until recently this last species had been listed as absent north of the Saddle but the recent sighting of a solitary specimen on a cliff in the Mangatera, together with the consistent rarity of Aristotelia in the northern half of the range, suggests that these had already been reduced by browsing before the main southward movement of deer began.

In addition to the species mentioned, Coprosma foetidissima has been almost invariably hard-browsed, though survivors are frequent. Its recovery in areas of high-priority hunting such as the Waipawa headwaters is now becoming conspicuous. Under the scrub Polystichum vestitum, once abundant and Ranunculus insignis, formerly luxuriant along watercourses, only survive reduced in number and size.

The main subalpine scrub species are listed downwards in the altitudinal sequence in which they occur (List 7). Others of minor importance are Gaultheria subcorymbosa and Pimelea buxifolia south of the Waipawa Saddle the Hebe truncatula group where scrub is encroaching on to scree, and of very local occurrence Dacrydium bidwillii, though this is more characteristic in snowgrass in the neighbourhood of bogs. The ball koromikos H. odora and H. venustula and the whipcord H. subsimilis only enter the margins in stunted scrub and are hardly typical scrub species.

CENTRAL: SUBALPINE TUSSOCK

Above the timber line the most widespread formation is tussock grassland dominated by a uniform, rather narrow-leaved form of snowgrass, Chionochloa pallens, distinct from either of the two species that occur in the Tararua Range. Where the divide is narrowest tussock mainly occurs on the easier western slopes, but where the crest broadens out to north and south, and particularly on the

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 29

wide summits of the Hikurangi Range and Mokai Patea plateau, it covers extensive areas. At lower altitudes on the Mokai Patea snowgrass is replaced on wetter ground by red tussock below 4,500ft. Taramea (Aciphylla colensoi), formerly associated with snowgrass in sufficient abundance for its dagger-like leaves to be mentioned by Colenso as a considerable obstacle to his lightly clad Maoris, and giving its name, Puketaramea, to a peak on his route, has since become comparatively rare. It is obviously keenly relished by browsing animals -certainly by deer and perhaps by hares – and over the past 30 years has become confined to inaccessible sites except in one or two limited localities. There is evidence of its recovery in the past 4-5 years, presumably connected with a decline in deer population, accelerated towards the eastern side of the range by intensive hunting.

Low-growing shrubs are scattered through the tussock, and a number of low-growing plants, most of them herbaceous, are plentiful beneath them (List 5A). On more exposed sites, tussocks are more widely spaced and less luxuriant, allowing low-growing plants such as Celmisia spp. to appear in greater variety and to form a larger proportion of the ground cover. In still more exposed sites fell field appears: a surface of lichened rock fragments carrying an open community consisting partly of plants associated with snowgrass (which commonly persists in scattered stunted tussocks), but with the addition of certain plants more or less confined to that situation (List 5c).

CENTRAL: BOG

The main peat bogs lie on the western and northern plateaux and share in different degrees elements of a common flora. This has been most fully recorded in the Northern Ruahine and can best be dealt with in the account of that area. The upper part of the Mokai Patea is the most extensive area of peat bog lying outside the Northern Ruahine and within the Central Ruahine area as here defined.

Floristically this bog is most closely linked with the Northern Ruahine bogs and to a lesser degree with the western (Whanahuia) bogs (List 9).

Smaller bogs occur on the divide near Tupari, south of Te Atua Mahuru, and on the western end of the Hikurangi Range. In each case tarns with raised sphagnum rims or their relics are evident, but otherwise the associated plants in most cases are merely those of wetter sites in the neighbourhood. Near Tupari, however, a somewhat larger bog area (perhaps the traditional waterhole Ngaroro a Kahupakiri) carries a number of plants (for example, Drosera arcturi, Myriophyllum propinquum, Hypolaena lateriflora, and Geum leiospermum) which do not occur over a considerable area around but are characteristic of the larger bogs.

On the Mokai Patea peat formation is not now active except in one or two areas round tarns, and the erosion of peat or the invasion of its surface by tussock vegetation is characteristic (Moar). At higher elevations snowgrass is the tussock species, but below 4,500ft red tussock is increasingly prominent on wetter ground with snowgrass confined to drier sites. Buried timber has been observed in the vicinity up to nearly 4,700ft but not in the bogs themselves, and as far as investigation has gone it only occurs intermittently.

30 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

CENTRAL: SCREE

Screes, rock falls and shingle-choked watercourses are conspicuous through most of the Central Ruahine, particularly along the eastern fault scarps, an impressive example being shown in the aerial photograph of the Waipawa Saddle (Plate 1), where the contrast between the tussock-covered western slopes at the head of the Waikamaka and the great area of rock faces and shingle on the Hawke’s Bay side is strongly marked. There is also a considerable development of screes in some of the inner valleys, particularly those of the Makaroro, Mangatera, Kawhatau, and Pourangaki. A scree system in the northern head of the Mangatera, is closely associated with a series of scarplets and on a small scale shows the most conspicuous relationship of faulting to scree formation in the range.

Where the whole face of the range can be viewed, as for example the Hikurangi Range from across the Kawhatau valley, or Te Atua Mahuru from Remutupo, it is clear that there is some sequence of scree formation. A former system or systems of screes now completely revegetated in snowgrass or scrub has interspersed with it, rather than superimposed on it, a comparatively recent active system. The general impression suggests two or more cycles of scree formation. Elsewhere individual screes occur in varying stages of stabilization, which suggests that scree formation can be a continuing process, each scree reaching maturity when its head has eaten back to the crest of the ridge. At this point, where the slope eases out to a surface of fine rubble or clayey soil, a scattered community (see List 6A) is conspicuous.

Further down the slope characteristic scree species with wide-ranging root systems frequently occur in running shingle (List 6B)

As the base of a scree becomes stable it is invaded by Hebe truncatula, a pioneer species of such sites m the Central Ruahine, where it forms characteristic pure sands whose dense canopy opens up after a period of about 20 years. Though listed as a true species individual plants show variations, mainly in leaf shape, texture, and colour; in cultivation, when it is grown from seed, two flowering periods (November and February) are common, while some bushes consistently produce up to 80% of branched racemes. These characters suggest a hybrid origin, but the parentage is in doubt as the geographical and taxonomical considerations do not agree.

The process of recolonization has been followed on a 1,100ft scree opposite the Waikamaka Hut. It shows on a 1933 photograph as apparently bare shingle, and in 1939 was still free running shingle over almost the whole of its length. The Hebe then began to appear at the foot and inward from the flanks; subalpine plants and snowgrass started to move in higher up, and, although the scree had not yet eaten back to the crest and still had an overhanging lip corniced in winter scattered prostrate plants began to establish footing across the upper surface. This is now approaching a closed cover, while the lower third has become an almost impenetrable Hebe thicket. Between them a few lanes of loose shingle persist on which scree plants are becoming established, Epilobium pycnostachyum within the last five years or so.

One interesting pattern of scree occurs on the back of the Shut Eye Ridge facing the northern head of the Waipawa, where older screes are occupied by 50- to 60-year-old mountain beech and are now being undercut by a recent active scree. Charred timber has been found on either side of the valley, so it is possible that the beech regeneration and subsequent erosion are effects of a fire occurring about 1900.

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 31

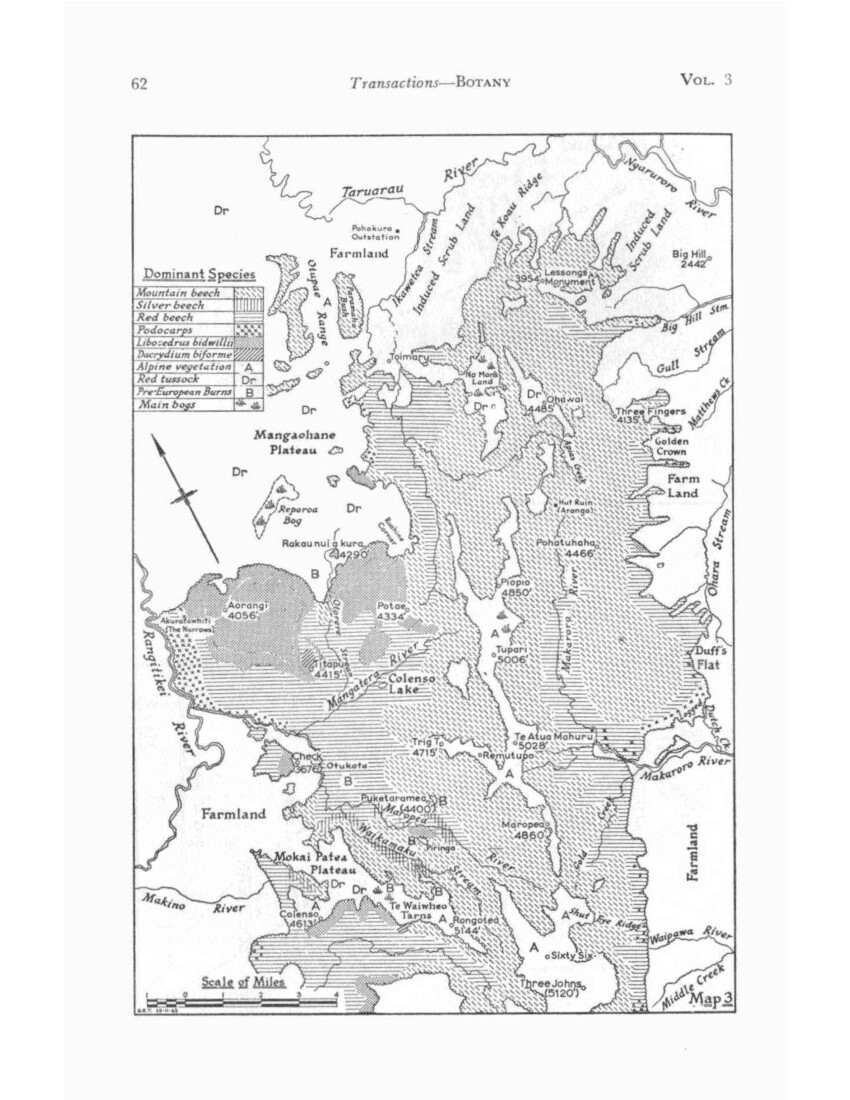

NORTHERN RUAHINE (Map 3)

The Northern Ruahine consists of three blocks – the NW and NE plateaux, and the Pohokura basin between them – each of which has botanical characteristics of its own. The NW plateau is a southerly extension of the Ngamatea plateau and its affinities are with the Inland Patea. Both the Pohokura basin and the NE plateau have closer floristic relations with Hawke’s Bay, so that the Northern Ruahine could be divided into NW and NE areas, though it is here treated as a whole. Several species with a northern distribution extend on to it, more especially on lo the NW corner, and a number of coastal species persist in the eastern gorges, while several species that are prominent further south drop out or become less prominent (e.g., leatherwood, and red beech).

Both plateaux at the time of European occupation were occupied by a mosaic of mountain beech and red tussock like the Inland Patea and Ngamatea country to the north. It is still a matter for speculation as to how far these were Maori fire patterns, as the evidence has been so generally overridden by European burning

The Pohokura basin between them, however, when first recorded, carried what was evidently an induced cover of tall kanuka scrub with islands of matai-dominant forest; it may be matched with the Omahaki basin downstream of it on the Kaweka Blowhard

One difference between the Inland Patea and Ruahine plateaux is the sharp falling off of the Taupo ash to a thickness of less than an inch, and associated with this the absence of subsurface charcoal. At the same time there is evidence (cf. p. 34) particularly in bogs, of the replacement of Dacrydium biforme by red tussock at about the level of the Taupo rush.

Almost the whole of the red-tussock grassland has been stocked with sheep, and for the most part burnt, over a period of up to 80 years, and cattle have been run on parts of it, though perhaps more recently. It was also the first part of the range to be heavily browsed by deer, so that both tussock and forest have been considerably modified from their pre-European state. Evidence of earlier Maori burning is still indefinite and undated, but seems likely, as it accumulates, to be recognized as important.

NORTHERN: PODOCARP FOREST

Vestiges of podocarp forest remain at several points round the margins of the area and in the Pohokura basin, generally at rather low altitudes, beech forest generally dominating above 2,000ft. The exception is an isolated area of podocarp-hardwood forest towards the head of the Wild Sheep Spur at nearly 3,000ft, between the Ikawetea and Makirikiri Streams. These remnants resemble those of the Kaweka Blowhard and differ from the rimu-dominant stands common elsewhere along the margins of the range in that matai is the dominant species, quite often associated with totara, though rimu is a fairly constant minor component. Kahikatea occurs frequently, but on the other hand miro is rather rare. With podocarp forest are associated such broad-leaved species as black and white maire. Mountain maire, though rare, occurs at Herrick’s Hut (1,500ft).

NORTHERN: RIVER CLIFF

In the gorges of the Ngaruroro, Taruarau, and Rangitikei Rivers at the lowest altitudes in the area (ca. 1,000ft) there occur a number of pockets of strictly lowland species which also occur at the other end of the range in the Pohangina and

32 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

Manawatu valleys. Myoporum laitum, Dodonaea viscosa, Rubus squarrosus, and the rupestral form of Hebe angustifolia var. parviflora are characteristic. The north-eastern communities have in addition a striking Hawke’s Bay coastal component (List 10) mixed with such Inland Patea endemics as Hebe colensoi and Myosotis eximia. There are also several miscellaneous and more localized species: Coprosma virescens and C. rubra (Rangitikei and Pohokura) an extensive colony of Solanum aviculare var. albiflorum (Big Hill Stream) and Hebe angustifolia var. arborea.

NORTHERN: RED BEECH FOREST

Except in the upper Ikawatea valley and in one or two stands of limited extent, as for example at Toimaru, red beech becomes infrequent and is absent from most of the area, its place being taken by mountain beech, and in the Paramaho Bush by black beech merging into a black-mountain swarm. The latter is a feature of some interest, as the Paramaho Bush lies in a zone several miles wide which extends westwards into the SW Kaimanawa Range and also makes its appearance in the opposite direction-to the NE on the Kaweka Blowhard, in which a black-mountain swarm is dominant in the relics of forest that remain. Elsewhere in the Ruahine Range, where black and mountain beech occupy different altitudinal belts separated by the red-beech belt, the two species are recognizably distinct, but where the red-beech belt thins out (as in the Makaroro mill workings which lie just outside the boundary of the northern area) with black and mountain beech present on either side of it, a narrow belt of hybrids occurs in the red beech along the 2,000ft contour.

Evidence has recently come to light from buried beech leaves on the margin of the Taupo shower in the Kaweka Range that there has been a change within the last 2,000 years in the composition of a black-mountain swarm (Cunningham).

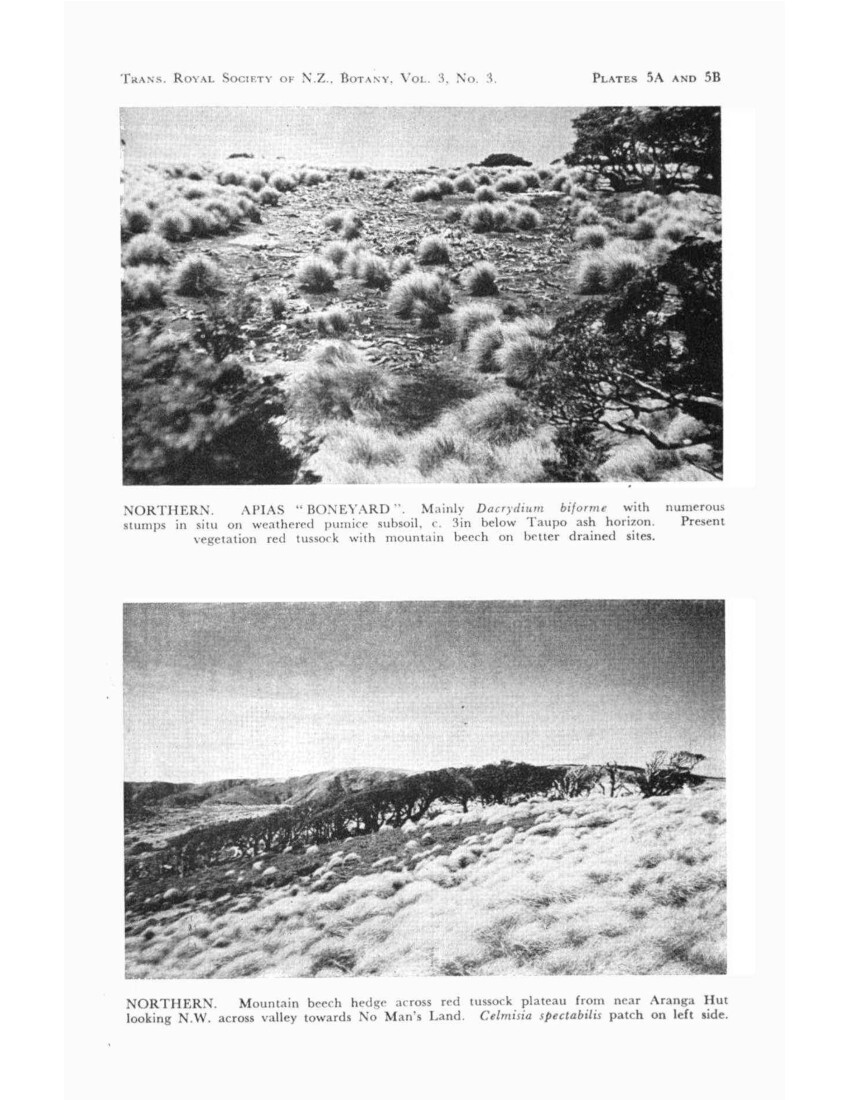

NORTHERN: MOUNTAIN BEECH FOREST

Few points in the area exceed 4,500ft, so that practically the whole lies within the altitudinal range of mountain beech. However, red tussock dominates the wider crests and easier slopes, with beech forest dominating the steeper slopes and narrower ridges. Tongues of forest or occasional clumps of trees may occur in the tussock areas, and narrow lines of wind-blown trees across the tussock slopes may persist and are characteristic (Plate 5B). These narrow lines appear to mark a change of slope or the margin of deeper peat. Thickets of stunted beech and Dacrydium biforme also huddle in troughs close to the highest point of the No Man’s bog (4,500ft), and here shelter from wind is an obvious factor of their persistence as well as depth of peat. The troughs appear to be due to the checking of Sphagnum formation under the dense canopy. Where the formation is more open the shelter of individual bushes favours Sphagnum, and mountain beech in this situation largely roots in it. Dacrydium biforme, however, tends to supplant beech where the drainage is poor. Cursory observations on No Man’s Land suggest about 1 ½ ft depth of peat as the limit for beech and something more than 3ft for Dacrydium. Along much of the level surface of the plateau an open type of beech/scrub forest occurs, with scattered crowns and a high proportion of dead trees over a dense divaricating scrub of browse-resistant or unpalatable species. The earliest concentration of red deer occurred here and they must largely be held responsible for this pattern, but there is also a longer-term cause. Clusters of dead beech trees tend to occur on waterlogged ground on which Dacrydium biforme is coming in; the entry of this species indicates an early stage of formation of peat bog.

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 33

Where forest occurs on the slopes the canopy is usually closed, but until recently undergrowth was sparse and on the eastern side almost completely absent even before goats came in from the Wakarara Range. Young beech regeneration is conspicuous at the present day along the brow of the plateau; but it is absent both from the crest and from the slopes under dense canopy. The relation of this to drainage and light is clear; its relation to browsing pressure is dealt with later (Appendix 1).

At the north-eastern extremity of the range cedar is associated with beech, but at lower levels and hence mainly on the slopes. It is not in great quantity and appears to be dying out, as dead trees are frequent in forest. In scrub, how ever, on the Pohatuhaha Spur at 3,300ft there is one notably vigorous all-aged stand, while occasional saplings occur at lower levels along the foot of the Pohatuhaha Range. A somewhat similar pattern of failure above and success below has been noted towards the other end of its range at Umutoi (Western Ruahine).

NORTHERN: TUSSOCK

The dominance of red tussock is associated with level or gently sloping ground and hence frequently with the formation of peat, certainly with a reduced rate of drainage and presumably with a higher soil acidity. Where snowgrass is associated with red tussock it shows a marked preference for drier sites, as on mounds of drift pumice (Ohawai). A tendency has also been noted along forest margins (Ruahine Comer) for snowgrass to replace red tussock.

As practically all areas of the Northern Ruahine carrying red tussock have been utilized for grazing accompanied by periodical burning, considerable modification has taken place. Where stocking and burning are still carried on introduced plants have appeared, with areas in which scab-weed communities have replaced tussock, extensively so near Makirikiri trig on the rim of the limestone scarp of the NW plateau.

On the NE plateau the tussock and topsoil have been removed from two or three localities, exposing buried timber in sufficient quantity to make it evident that the wide tussock slopes of Ohawai once carried forest. Both here and at Apias Creek, where the stumps are exposed in situ, this was predominantly Dacrydium (mostly D. biforme) forest, which at Apias was rooted above a horizon of weathered ash and a few inches below a Taupo ash horizon (Plate 5A). The Piopio exposures south of the plateau are in snowgrass but have also uncovered wood, in this case almost certainly Olearia colensoi. These exposures could have been initiated by the trampling of sheep, perhaps on a surface exposed by the burning of tussock, or later by the burrowing of rabbits or even later still by the trampling of deer. They have certainly developed through the action of wind on Ohawai (where drift dunes colonized by snowgrass have developed on their margins) as well as of water, the latter being more evident at Apias.

NORTHERN: BOG

The Reporoa and No Man’s bogs on the NW and NE plateaux respectively carry the largest and most specialized flora and the bogs farther south along the range show some relationship to them, as has already been mentioned in dealing with those on the Mokai Patea and near Tupari (List 9). Features common to all of them, though most developed in the north, are the shallow tarns with raised sphagnum rims, the association with red tussock, which may even mask the existence of peat, and the presence of ash horizons.

34 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

Reporoa Bog. This bog lies on the Mangaohane limestone at an altitude of 3,800ft and has been the most closely investigated botanically. Of 119 species listed by Druce in 1948, 13 were not previously recorded north of Cook Strait, and a further 33 had been recorded in the North Island only from the Tongariro National Park.

Peat profiles show a depth of 16ft and the main features of their pollen are the steady increase from the base of the beech as against podocarp pollens, the prominence of rimu as against all other podocarps, and the extreme scarcity of cedar.

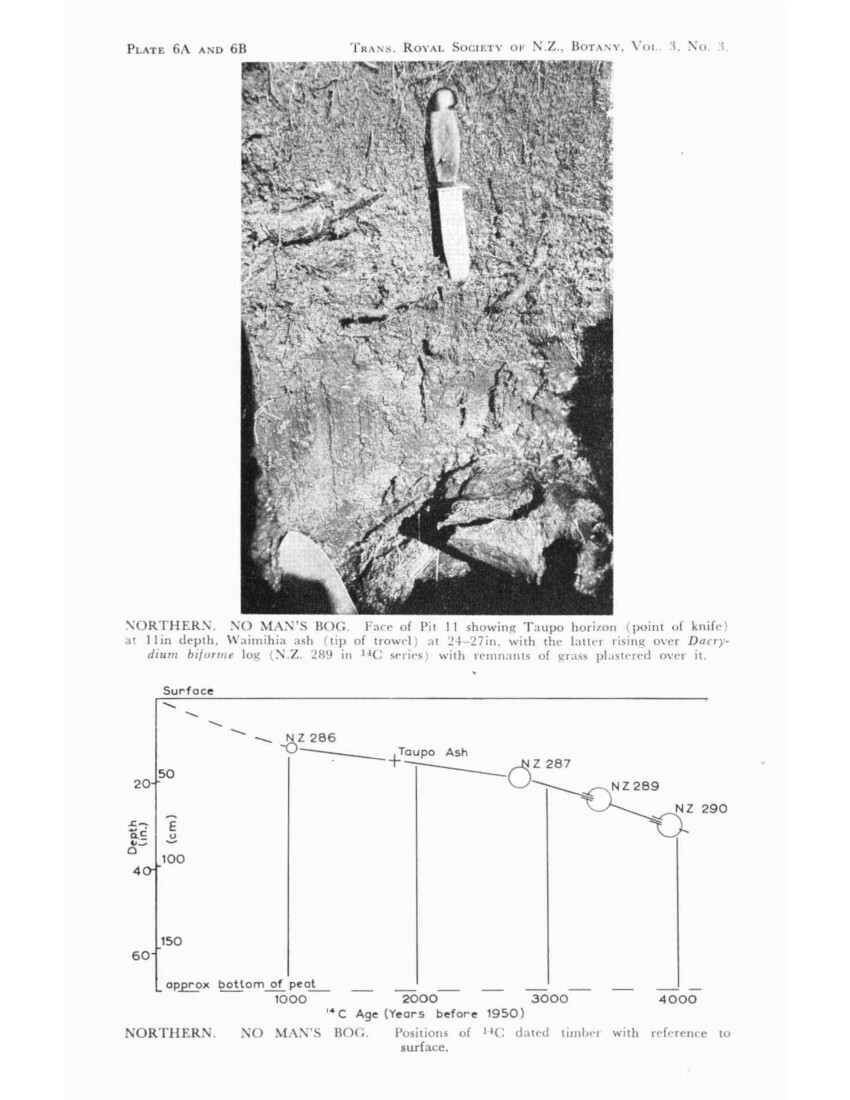

No Man’s Bog. This bog lies at an altitude of 4,500-4,300ft about the timber line and several hundred feet above Reporoa. Red tussock covers most of its surface, with a little gnarled and frequently moribund Dacrydium biforme and mountain beech where the peat is shallower. The blanket of peat is generally 5-6ft deep, its chief features being the clearly defined ash horizons and the abundance of preserved timber (Plate 6A). It has been found possible with a sounding rod to distinguish not only logs but layers of twigs and even volcanic ash to depths exceeding 5ft. By this method some 200 probes have been made on a grid covering about an acre which show a fairly even distribution of timber with a possible maximum a little below the Waimihia ash over a period of several thousand years (that is, from more than twice the depth of the recognizable Waimihia ash shower) until about the time of the Taupo shower (1840 years B.P.) after which there is a pronounced diminution in the amount of timber.

Samples of timber have been collected to a depth of 30in, identified by wood structure, and a selection of them carbon dated (Grant-Taylor and Rafter 1962). Except near the bog margins all timbers have been identified as Dacrydium and most as D. biforme.

A plot of C14 ages against depth suggests that the rate of peat accumulation had been decreasing for a long period prior to the Taupo shower, followed by an increase (Plate 6B). The progressive disappearance of the earlier ash showers towards the margins shows that this bog has been expanding laterally for several thousand years.

The present distribution of Dacrydium biforme on the NE plateau shows that it will flourish on deeper peats than mountain beech will tolerate. Buried Dacrydium logs with a maximum of at least 4ft of peat below them are widespread in the No Man’s bog and, as the frequency of timber falls off sharply above that level, this suggests at first sight that the depth of peat is the limiting factor. Against this is the abundance of subsurface timber in the form of stumps in situ on clay subsoil as well as logs further along the plateau (Ohawai and Apias). The presence of the Taupo ash horizon in all these exposures shows that the replacement of timber by red tussock on these different kinds of sites was approximately contemporaneous. Some indirect association with the Taupo eruption is a possibility, as for example fires spreading on the periphery of the area to the north where hot ash destroyed the vegetation.

Pollen analysis shows a dominance of beech over the whole period of peat formation, with a general decrease of Dacrydium biforme type pollen prior to the Taupo shower and only intermittent appearance since. The profiles from No Man’s do not match those from the western (Mokai Patea and Whanahuia) bogs, but no detailed comparison has yet been possible (N. T. Moar, pers. comm.).

No. 3 ELDER – Vegetation of the Ruahine Range 35

NORTHERN: SCRUB

As a result of stocking and burning of the more open country and prolonged browsing of the whole area by deer, there is perhaps no natural scrub formation left in the area. Forest undergowth [undergrowth] (List 8) appears to have developed into a dense, divaricating scrub form, particularly where mountain beech is dying out and ceasing to form a canopy. Olearia colensoi only occurs towards the southern boundary; seedlings of Senecio elaeagnifolius are remarkably widespread on protected sites, but the rarity of adult plants suggests that this species has been reduced by browsing.

Towards the NE extremity of the range fire-induced manuka scrub is extensive up to about 3,500ft. This resembles the scrub of the Kaweka Blowhard in species composition and relative abundance of Leptospermum ericoides. Its heavy defoliation, presumably by opossums, behind Kereru is a recent (1962), and on the steep slopes, an unwelcome development (List 11A).

An open scrub community on higher exposed crests, particularly the Otupae Range and Te Koau Ridge, also shows affinities with that of similar situations in the Kaweka Range. Manuka takes the same prostrate form, but the frequency of clumps of Griselinia littoralis huddled in the lee of small hummocks is peculiar, especially in the presence of deer (List 11 B).

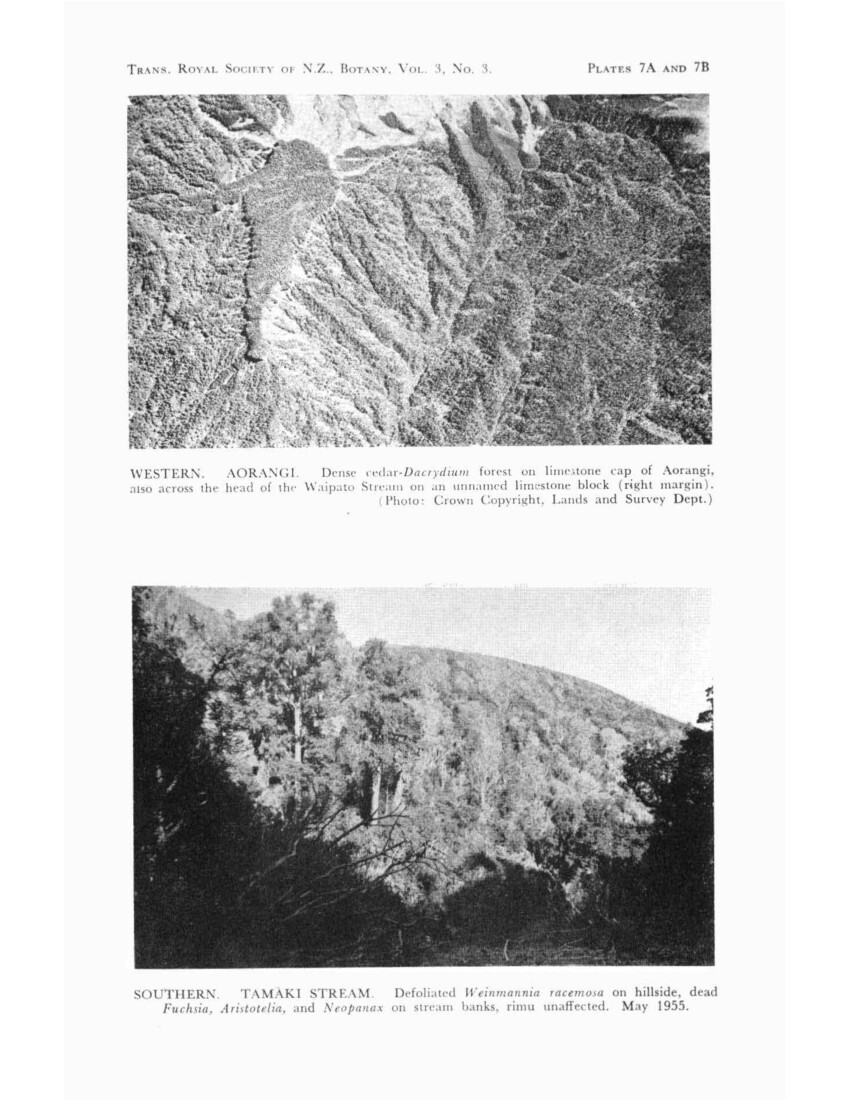

NORTHERN: LIMESTONE CLIFF

Besides the river-cliff communities which have been described in an earlier section several limestone blocks (Aorangi, Rakaunui a Kura, and Potae) exceeding 4,000ft in height, which are striking features along the southern margin of the NW plateau, support a distinct assemblage of plants on their cliffs and in the numerous clefts of the plateau itself (List 12).

WESTERN RUAHINE (Maps 3 and 4)

The clear-cut line of cedar forest across the end of the Mangaohane tussock marks the northern margin of the Western Ruahine forest. Cedar forest occupies most of the Mangatera basin and runs south along the outer flank of the range till the Oroua River emerges, then continues in an increasingly modified form as far as the mouth of the Pohangina Gorge, where it is indistinguishable from the forest of the Southern Ruahine in which cedar is no longer dominant.

Although cedar occurs throughout the range, as does Dacrydium biforme, it is only where mountain beech is absent that one or the other species can dominate the timber line so that on this basis the boundary between Central and Western Ruahine follow the edge of the mountain-beech forest. This boundary begins near the divide at Potae and runs obliquely SW across the Mangatera valley to the Mokai Patea. A narrow strip of cedar forest continues south along the western face as far as the Whanahuia Range. Cedar continues to dominate on the outer face of this but on its inner side Dacrydium biforme becomes increasingly important in a wide belt running obliquely SE across the Oroua and Pohangina valleys to the Hawke’s Bay side of the range.

As earlier stated, the upper Pohangina valley could be treated as a separate natural area. but for simplicity’s sake is here considered as an extension of the Western Ruahine area which then is distinguished by the absence of mountain beech, the presence or red beech, and the dominance of cedar and/or Dacrydium biforme at the timber line.

The Western Ruahine thus consists of two main areas, a triangular one in the north and an oblique band across the range in the south, joined by a narrow outer strip across the foot of the Mokai Patea tussock.

36 Transactions – BOTANY VOL. 3

WESTERN: PODOCARP FOREST

Podocarp forest has generally been cleared and milled along the western flank of the range. Such vestiges as remain are mainly rimu scattered through redbeech forest, but this may not give a true indication of the composition of the virgin podocarp forest. In the two or three unaltered areas of podocarp forest of any size that remain – on the western slope of Aorangi and in the Pourangaki valley, to which may perhaps be added a third in the Oroua valley – rimu is not generally the dominant podocarp.