THE SHIPPING STORY

… from front cover

“If it is not produced, it cannot be sold or shipped.”

To a large extent the shipping department of a freezing company dictates the most important facet of the company’s operation – finance. Without shipment the company is not paid.

A major portion of our meat trade hinges on the correct forecasting of shipping space, which has to be nominated two months in advance.

Stock is usually in store for one to three months prior to shipment. But as the company has paid for the livestock at the time of initial processing, any delays to shipping will mean decreased or delayed revenue and a direct loss to the company.

800,000 tonnes

With 800,000 tonnes of meat being exported nationally each year in addition to slipe wool, pelts, hides and casings, it is no mean feat to ensure the orderly movement of cargo. Ships do not just materialise. There are daily assessments and communication between producer, supplier, buyer and shipowner to ensure that ships are available as and when required.

“To those not immediately involved shipping is a matter of a ship in the harbour or at the wharf – something going on or coming off,” Mr Sloane commented. “But it is rather more organised than that!

“Even when our products are loaded, that is not the end. We are involved with harbour boards, transport operators, the MAF, NZ Railways, shipping companies, producer boards and, of course, the ultimate buyer who requires full and accurate documentation for the product shipped to meet customs and agriculture department requirements both here and at the destination.”

Conference lines

About two-thirds of the company’s tonnage is lifted by ships within a conference or semi-conference shipping concept, with the balance shipped by charter vessels.

The Northbound (United Kingdom – Continent – Mediterranean) Conference is contracted by the NZ Meat Producers’ Board in conjunction with the NZ Dairy Board, and covers freight costs and frequency of service and calls. Similar conferences operate for shipments to North America, Japan and Korea.

The guarantee of refrigerated meat cargo (and dairy products) also brings benefits for other exporters, who can negotiate for the excess space available on the contracted services.

Improvements

Most traditional markets are now served by containers, which have brought obvious advantages to the industry and the consumer alike. The product is handled less frequently, delays are minimised with better product out-turn, and temperature and hygiene control have been improved over conventional shipping.

As containers are treated as a unit from packing through to wholesaler, processor and distributor, the contents are not touched and the product arrives in top condition.

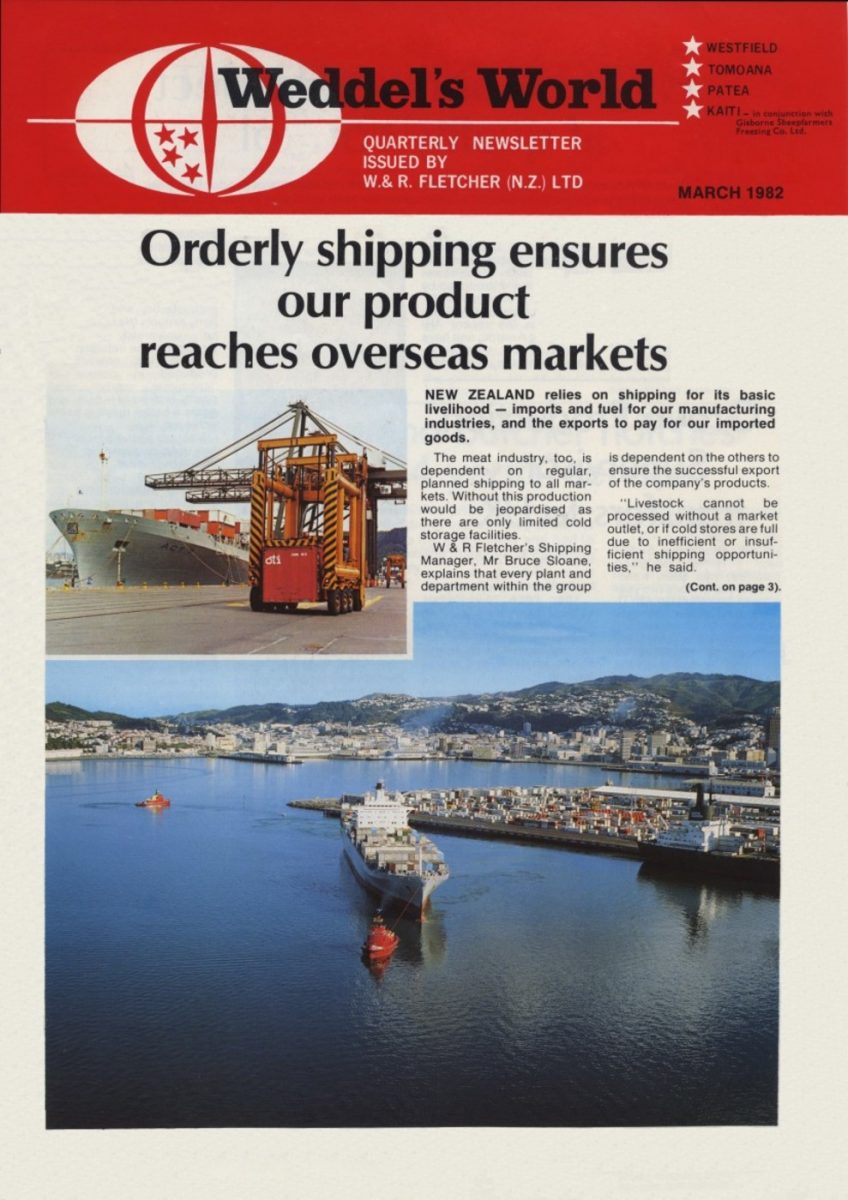

Cover photos:

The Act 7 sails for the UK after loading a cargo of refrigerated meat at the Port of Wellington.

The Act 7 and its sister ship, the Australian Venture, are the Blueport line’s largest vessels and two of the four largest reefer ships in the world. With a length of 248.58 metres and dead weight 39,454 tonnes, the ship can hold 2152 containers (1119 refrigerated and 1033 general containers).

The smaller photo shows containers being loaded from the terminal stack by straddle carrier. The crane can lift three eight by twenty-foot containers at a time, stacked vertically.

Tomoana butcher notches up 54 years’ service

WHEN Lawrence (Milky) Mills started his first job as a labourer at Tomoana, he didn’t expect to be there for long. He was only 13 years old at the time, and had to obtain special approval from the Inspector of Factories before being allowed to stay.

Times were hard, and there was no unemployment benefit for those who didn’t manage to find a job. But the young lad proved to be a keen worker and stayed on – for a grand total of 54 years!

Too young to be a butcher at first, he stayed permanently on piece work and “did the hooks” in the lunchtime. When the chains came in 50 years ago, he looked after the six butchers in the abbatoirs [abattoirs].

His starting salary was $157 a year with no provision for overtime, although he worked until eight o’clock at night. There were no showers for labourers, only “three old tin things”, and most bosses were “really tough”.

“They had to be – they were dealing with tough men in those days,” he says. “You were too frightened to complain in case you lost your job.”

Some incidents still leave him grinning, though.

“I reckon I was the first streaker there,” he told Weddel’s World. “We had a three-foot trough of warm water where we scalded the pigs, and I thought I’d have a bit of a swim.”

Unfortunately the manager appeared on the scene and young Milky took off, leaving his clothes behind. “I got a tune-up!” he added.

The earthquake of 1931 was another unforgettable experience.

“When the shake came an office fell against the door and no-one could get out – we finally got out down the sheep race.”

Milky has lived on three acres of land outside Hastings since 1950, when he bought the property for 50 pounds. He also used to lease additional land for cropping and sheep, getting up at 4 am to do his chores.

He would arrive at the works at 6.30, an hour before starting time. “l don’t believe in rushing,” he says; explaining that he had time to sharpen his knives and enjoy a cup of tea before getting down to the day’s work.

Many interests

Milky has been involved in training horses, played Rugby for Napier’s Marist Club and still enjoys watching local games. A large garden also keeps him occupied. But he and Mrs Mills both enjoy travelling to race meetings in Wellington and Rotorua, as well as the Hawkes Bay area.

He also likes to keep in touch with some of the friends he made during his many years at Tomoana. “I’ve met some great fellows there,” he says. “I reckon I’ve met as good as any in the freezing works.”

Photo caption – MR and Mrs Lawrence (Milky) Mills enjoy a brief moment of relaxation. Milky retired last year after 54 years at the Tomoana Freezing Works in Hastings.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.