Page 174

Games she reached new levels in each of the three rounds and came fifth in the final, two places ahead of the other New Zealander. Sad to say, Guthrie did not go ahead from there, as I’m certain she had the ability to do. In the next two national championships she was not even a competitor. In 1976 and 1977 she made a brief reappearance for a couple of silver medals. But after that, nothing. The eastern Europeans did not waste athletes like Guthrie.

The ‘other New Zealander’ whom Guthrie beat at the Games was none other than Matthews, making her second comeback. It is worth detailing the first of them, before the 1972 Olympics, to show what an athlete Matthews was. At that stage, remember, she had not run for four years, and the 100m hurdles was new to her experience.

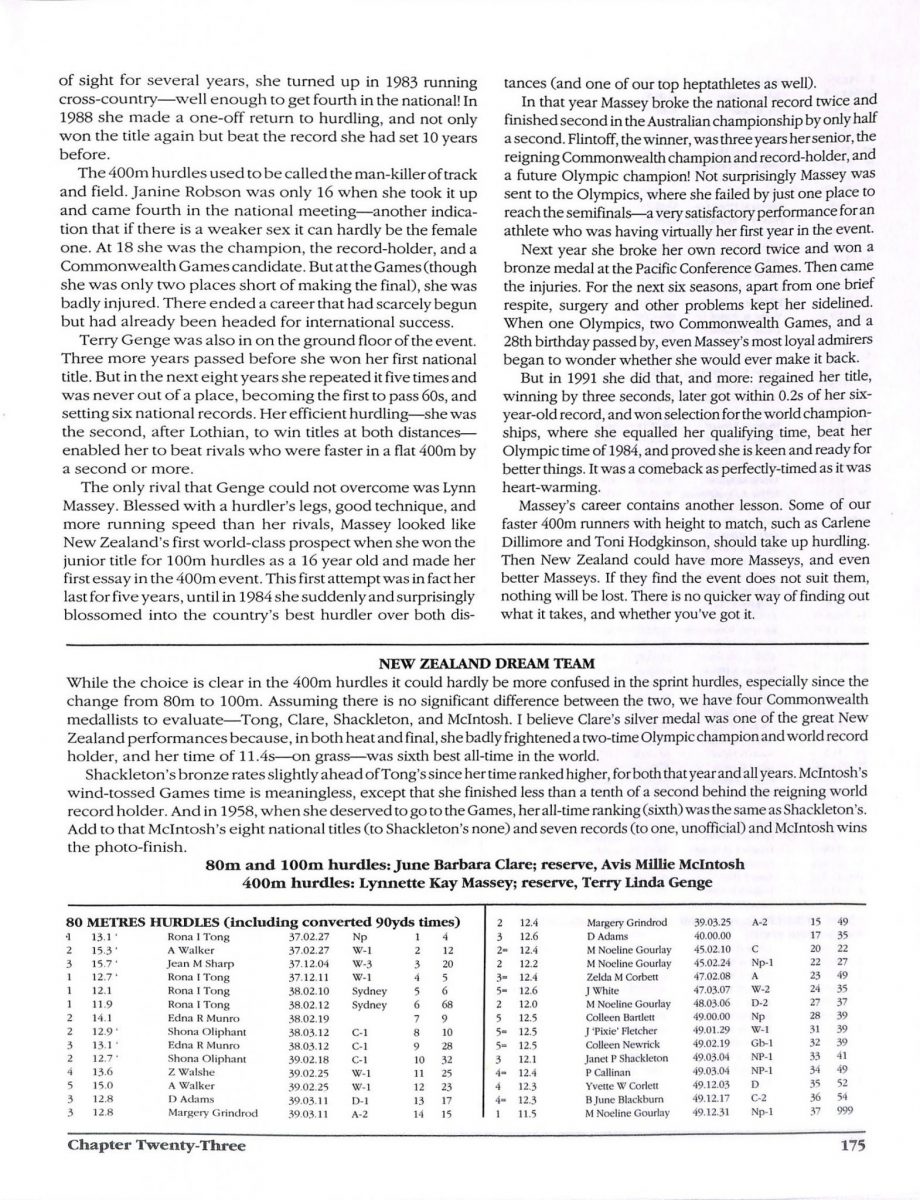

In her first attempt, even if it did have wind assistance, she put up a time of 14.0s. The national record was 14.5s. A week later, again with wind assistance, she did 13.6s. In the next six weeks followed times of 13.5s (wind-assisted), 13.9s (a record), and 13.6s (a handicap race, but otherwise valid). Later there were four more records of 13.9s, 13.7s, 13.6s, and 13.4s.

In her first season of the event Matthews had lowered the record by over a second. Again, as in 1966 and 1967, she was able to press Pam Ryan, Australia’s two-time Olympic medallist, to within a couple of metres. She was selected for the Olympic Games herself, put up her best automatically-timed performance, but got nowhere. The hopped-up Europeans were a second faster again.

Matthews More Capable

Matthews was also more capable than her seventh place at the Commonwealth Games would suggest. Her time for first in the heats was only beaten by two others, and (with the same amount of wind) equalled the time that eventually won the bronze medal. But how many athletes can expect to retire twice and still achieve their best?

If women were once regarded as the weaker sex, women athletes like Gail Swart have changed that idea. (Real strength, of course, is not just about lifting heavy weights.) Until 1975 Swart concentrated on sprinting, winning 10 championship medals including two golds in the 200m. She even picked up a silver medal in the long jump, which could have been her best event, since she cleared nearly 19ft as a 16 year-old beginner before giving it up altogether.

Once Swart turned her attention properly to hurdling she at once equalled Matthews’s hand-timed record – an improvement of 0.8s in one season. But, still unconvinced that she had made the right decision, she went back to sprinting for a year. When finally she got back into hurdling she made the Commonwealth Games team and got fifth. A couple of national titles later she retired, still only 25. Like Lowe, Swart suffered from such an embarrassment of talent that she never really settled down, and therefore never revealed her true capabilities.

After Swart retired the title passed to Terry Genge, who had already been runner-up three times. Genge would never profess herself a sprinter, as Clare, McIntosh, and Stuart were sprinters, and she owed her success to something those three lacked. She was tall – or, rather, long-legged – and thus she founded a new breed of hurdler that New Zealand had not seen before. Lynn Massey and Lyn Stock were of the same breed but, though all three were capable of well under 14s, Stock was the only one who really threatened to invade Matthews territory.

Through perseverance Stock became a fine technician, and through that technique was able to match Matthews’ (hand-timed) national record and beat her automatic times. Indeed Stock twice returned 13.67s, compared with Matthews’ 13.69s. The first time was in the 1985 Pacific Conference Games, where she won the bronze medal. The second was in the 1986 Commonwealth Games, but then she could not get past the semifinals. Why not? Because technique, however perfect, was no defence against opponents who could have made the New Zealand team as sprinters. One of them, in fact, could have broken our 100m record by over half a second.

The only hurdler of recent times with the necessary speed has been Helen Pirovano, from – where else? – Hastings. Already an international hurdler at 17, Pirovano hit the front a clear leader in 1987, when she won the New Zealand senior and Australian junior titles and was second in the Australian Open. In 1989 she was champion of Australia, a solid achievement because over the years Australia has won seven Olympic medals, three of them gold ones.

Pirovano has the fastest time by a New Zealander under any conditions, 13.47s (Wind-assisted), in the semifinals at the 1990 Commonwealth Games. In the final she was eighth in 13.61s and so became the first holder of the national record for automatic timing. She also ran in the 100m, after coming second in the national championship and returning very fast (but wind-assisted) times of 11.50s and 11.52s.

Pirovano, too, is a superb technician, and possibly the world’s fastest hurdler for the height. But there again is the catch – height. We still cannot produce a hurdler with the height and pace of Matthews who also has the technique of Stock or Pirovano, the inspiration of Guthrie, the durability of McIntosh, the fighting qualities of Stuart, the smoothness of Lothian, the nimbleness of Clare, and the zeal of Gourlay.

If we ever do, you will probably find her in the Hastings club – like Rona Tong, Margaret Stuart, and Helen Pirovano. What a trio!

400M HURDLES

During the 1970s the 400m hurdles became established as an event, but no-one was able to establish the kind of domination that is common in other events. Four different athletes won the first four titles; indeed to date (1992) the 17 titles have been shared by no fewer than eight athletes.

Among the early pioneers I would especially mention Marion Prior, who was the first to bring 60s within reach but gave up athletics after only two more seasons; the incomparable Karen Green; and Yvonne O’Brien, who set a national record and was a leading figure for four years.

Green was in at the start, winning two silver medals, followed by a title in record time in 1978, After dropping out

174 Athletes of the Century

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.