- Home

- Collections

- HOLLYWOOD G

- Various

- Colenso - The Man

Colenso – The Man

COLENSO – THE MAN

It is fitting that a Colenso anniversary should be commemorated in Napier on the Brown/Herschell Streets site where there has been a cultural centre for 96 years, and where now there is an ethnological Museum and a Library devoted to New Zealand history.

With increased knowledge of Colenso interest tends to be centred less on his successes than on the inherent qualities which animated all his work. Other men could have achieved success as printer or missionary, scientist or philologist etc. But could many have reached the same high levels in several spheres and done so despite frustrations and disappointments such as were suffered by Colenso?

To see the man for what he was one must know something of his beginnings. Colenso’s early life provided a preparation for what was to come for he was not brought up for soft living. He had a sufficiently sound education in a private school to whet his appetite for more and give him ability to acquire it. Whether he learned anything of a second language is not evident but it is recorded that a few years later he wished to buy a book from which he might study Greek on the voyage to New Zealand. At the age of 15 years he was articled to a Penzance printer who was also a book-seller. In his term of six years he used his opportunities to advantage. He read the books available, he joined the local Natural History Society and he learned to see and record what he saw. Being of a religious turn of mind he took part in church activities. At the end of six years he was an efficient young printer and bookbinder. He sought work in London.

The London firm which printed for the Church Missionary Society engaged the young man as a compositor. He used his free time to wander about London. He often visited the British Museum and the Zoological Gardens at Kew, he attended churches other than the denomination in which he had been brought up and found pleasure in a more evangelical type of worship than he had hitherto experienced. This did not make his relations with others of a High Church persuasion as easy as they should have been. Soon he heard the Church Missionary Society required a printer for New Zealand. He had a keen desire to visit distant lands. When he was engaged he had not inquired what his salary was to be. The competent printer was to receive £30 a year and living such as was given to the workers supplied from among the convicts in New South Wales. But Colenso had never had money to spend on anything but necessities.

With other people bound for the Mission field Colenso set sail on the 18th June 1834. While waiting in Sydney for a ship for New Zealand he was kept busy at the Mission Station there. He landed in the Bay of Islands on the 30th December 1834. A cumbersome press was man-handled from the sailing ship to the shore at Paihia and along to the printing-house where he too was domiciled. Here a shock awaited him, one which could have been spared him. In London he had not been permitted to see or to supervise the packing of the equipment for his craft. What culpable ignorance of New Zealand conditions was shown by the staff at Headquarters, London! The New Zealand station had been efficiently controlled for about eleven years so orders must have gone to London but they had

2.

not been filled.

Now Colenso must “make bricks without straw”. The difficulties were truly daunting. There was no trained help for him except that of Mr Wade, nominally his press superintendent, actually he was generally given other mission work. Faulty packing had caused severe breakages in the press and with the type etc. With the help of the mission blacksmith Colenso had to make new parts with what was available in the isolated country. Moreover many essential adjuncts for his craft had not been sent. The list of missing articles is incredible. There was no compositors stone, “cases, leads, rulers, ink-table, roller stocks or frames, lye brush or potash”. There was no page-cord, cardboard or printing paper. Fortunately Colenso had his own compositors stick.

To order from London through the Society would delay printing for perhaps eighteen months. There was an irregular and infrequent sailing ship service to Sydney. Surely the difficulties could be considered insurmountable yet in less than two months the first edition (2,000 copies) of the FIRST COMPETENTLY PRODUCED BOOK IN NEW ZEALAND was ready for circulation. The Maori people were to read the first book made in their country, and in their own tongue; they were to read the portion of the Scriptures – the Epistles to the Ephesians and the Philippians. There was an instant demand for it so the press was kept busy with a second edition, and hymn and lesson sheets. It was no 40 hour week for Colenso, it was a day-break to night-fall task with no time for private interests for on Sundays he had the duties of a catechist. He had now proved both his proficiency in his craft and his ability to overcome difficulties.

Three years later Colenso completed the first edition of THE NEW TESTAMENT. It was an edition of 5,000 copies of 356 pages of printing and he composed, printed and bound these himself. At the time of his death in 1899 Copeland Harding, a skilled printer himself, paid a tribute to Colenso when he said he thought the New Testament printed in 1837 was one of the most wonderful productions that had ever been issued from a printing press – when the imperfect outfit provided was considered.

The rapid publication of these two books brought about a stablization of the language which now had a scientifically based alphabet, a system of spelling, a printer grammar book and vocabulary – all prepared in England. The books had a profound effect on the Maori people who were natural orators. The poetry of the Scriptures entered into their written and spoken English. Surely it may be considered that Colenso had an important part in introducing good literature to the Maoris.

His printing craft enabled Colenso to share in an historic occasion for, by order of the British Resident and of Governor Hobson, in 1840 he printed circulars and proclamations and well composed copies of the Treaty of Waitangi. He was present at the signing; he for one could understand the emotions of the signatory chiefs as they ceded their land to the Crown. His “history of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi” was adopted as the official account. He also printed the first Government Gazette. As a producer of books for every stage of which he did the work Colenso was at the top of his profession. Old well-used copies of the New

3.

Testament show the quality, the enduring quality of his work.

From round about Paihia and to the north Colenso collected specimens of shells and insects. His interest in Natural History was soon to be strengthened by those who encouraged him to travel along the road that would show New Zealand to the scientists of the Old World. Little known New Zealand was then on the route to a more distant and less explored land. In Paihia Colenso was to meet three scientists of note. On Christmas Day 1835 he saw and heard Charles Darwin, the great botanist and writer. Of more importance to him was his all too short friendship with Allan Cunningham who in 1826 had made known something of New Zealand botany and now in 1838 came to Paihia. He and Colenso worked together when possible. Colenso had the unforgettable happiness of gathering plants with his new friend by the waterfall at Kerikeri. Here the spray gave rise to a vigorous growth of a greater variety of plants than was found in any other accessible place. He corresponded with Cunningham who was probably his first congenial friend in New Zealand, a friend who procured for him in Sydney necessary botanical material but who soon was to die. He helped and encouraged the young printer-botanist and through him another important contact was made in 1841. This was a momentous year. Colenso’s work impressed Lady Jane Franklin. She with her husband, Sir John Franklin, Governor of Van Dieman’s Land, had done much for the encouragement of science in the Southern Hemisphere. On her return to Tasmania from Paihia she sent Colenso a botanical microscope. He was asked to contribute to the newly founded “Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science” – the controlling society of which he had been elected a corresponding member.

A still more important event was to occur in August 1841. “Erebus” of the “James Clark Ross Expedition to the Antarctic” came in to the Bay of Islands and remained till November. The brilliant young scientist, Joseph Dalton Hooker, came into Colenso’s life. He carried a letter from Captain King, Allan Cunningham’s friend, for Colenso. He visited him and recorded seeing 150 species of shells, many insects and some minerals. From then on Natural History in one or other branch was to permeate Colenso’s life. He was not free to join Hooker as often as they wished, but often enough to learn much of plant hunting and to begin a life-long friendship. With increasing confidence Colenso sent specimens to Sir William Hooker. Surely there were outstanding qualities in Colenso which caused him to be accepted as a fellow traveller on the same road by these friendly people.

Some of the most important of the journeys made by Colenso took place while he was still at Paihia. He had amazing energy. In less than ten years he crossed the North Island from east to west by at least three routes. He walked its length from Cape Maria Van Dieman to Cape Terawhiti using varied routes. He explored his mission district, an area of approximately 10,000 square miles – almost a quarter of the North Island. Much of the country had not previously been

4.

seen by a European. He was accompanied by a changing group of natives as he visited different tribes, often those of famous fighting chiefs in remote pas. He was always accepted and respected. The Maoris were quick to recognise his integrity, his prowess and his devotion to duty. Never did he cease to add to his knowledge of the country and its rare treasures. From his notes and compass bearings he traced his route on a map. He showed the position of pas, available fiords, course of rivers and other data gathered during his exploration of the area from the East Coast through the Urewera, Waikaremoana, Rotorua, Tauranga, across to the Waikato, by canoe to its mouth, along the coast to Manukau Harbour, across to Auckland thence to Bay of Islands. His plan was sent to Arrowsmiths, mapmakers, London, and his data was included on the next map of the North Island.

Rarely in existing records does one read of Colenso carried away by intense pleasure so a passage from his diary is quoted. It tells of his first attempt to cross the Ruahine Range. The attempt failed in its objective but was far from fruitless. He wrote in 1845: ….. “When at last we emerged from the forest and the tangled shrubbery on its outskirts on to an open dell-like land just before we gained the summit, the lovely appearance of so many and varied, beautiful and novel wild plants and flowers richly repaid me the toils of the journey and the ascent, – for never before did I behold at any time in New Zealand such a profusion of Flora’s stores ….. I was overwhelmed. I have often seen pleasing botanical displays in many New Zealand forests and open valleys …. but all were as nothing when compared with this …. either for variety or quantity, or novelty of flowers – all too – in sight at a single glance ….”

Sheer necessity forced him to take off coat and shirt and to form bags which, with his hat, carried his rich treasure to camp. While the natives slept he packed his “darling specimens” which he planned to send to Kew Herbarium. Some were named for him as their discoverer. He wrote to Sir William Hooker that he had sent “beyond 600 specimens hoping that 300 at least will be found desirable and 50 or more entirely new ….”

Long journeys with natives caused Colenso to offer his services as a travelling missionary. He wished to return to England to qualify as a priest and marry but was not given leave. His training at St. John’s College, Auckland was not complete when he, as a Deacon, was put in charge of a new Mission Station in Hawke’s Bay. The marriage of convenience arranged for him was not happy through incompatibility. Happiness was found in work. In eight years of occupation of the Mission he established his district on a spiritual basis. The Spectator of Wellington in 1846 reported that Mr Colenso did all he could do to uphold the law. There was then no European authority but Colenso in the district. He tried to settle differences between the natives and men from the sea who often visited and sometimes violated the coastal settlements. He insisted on a return of goods “picked up” by natives from ships. His influence made for a peaceful penetration of settlers in the province.

5.

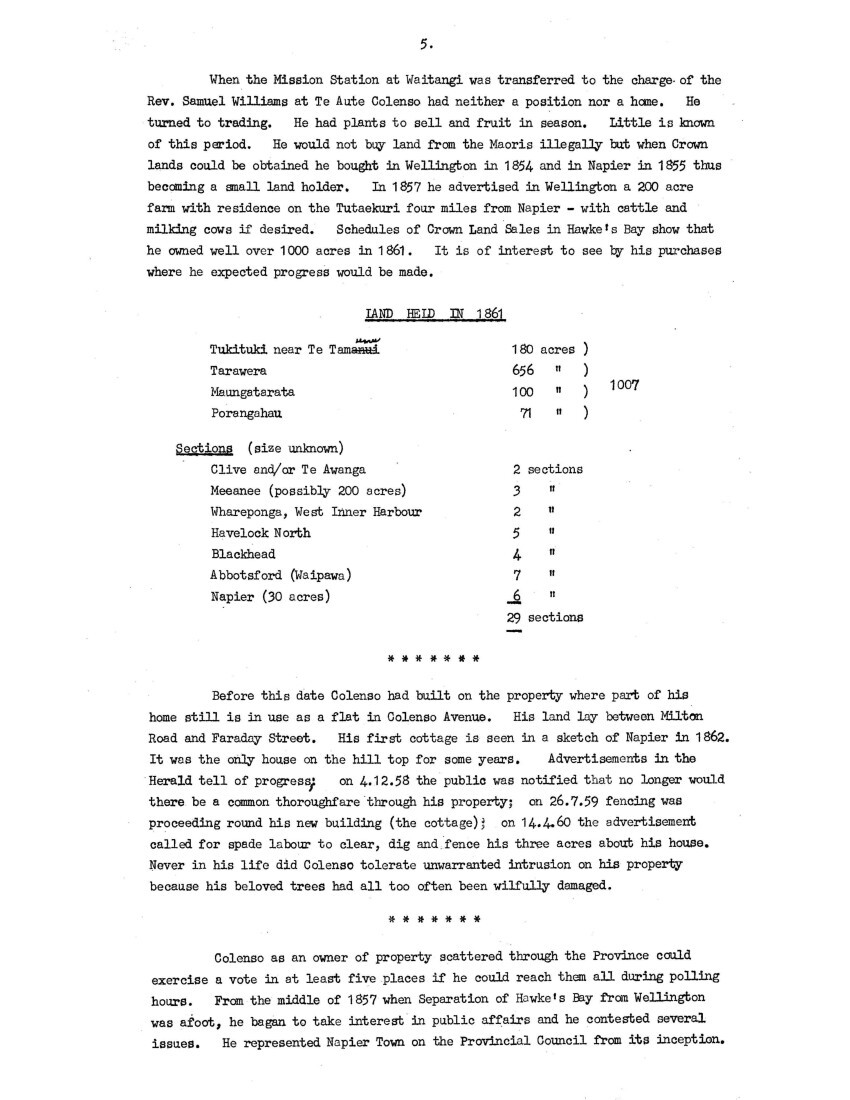

When the Mission Station at Waitangi was transferred to the charge of the Rev. Samuel Williams at Te Aute Colenso had neither a position nor a home. He turned to trading. He had plants to sell and fruit in season. Little is known of this period. He would not buy land from the Maoris illegally but when Crown lands could be obtained he bought in Wellington in 1854 and in Napier in 1855 thus becoming a small land holder. In 1857 he advertised in Wellington a 200 acre farm with residence on the Tutaekuri four miles from Napier – with cattle and milking cows if desired. Schedules of Crown Land Sales in Hawke’s Bay show that he owned well over 1000 acres in 1861. It is of interest to see by his purchases where he expected progress would be made.

LAND HELD IN 1861

Tukituki near Te Tamamu 180 acres)

Tarawera 656 acres)

Maungatarata 100 acres) 1007

Porangahau 71 acres)

Sections (size unknown)

Clive and/or Te Awanga 2 sections

Meeanee (possibly 200 acres) 3 sections

Whareponga, West Inner Harbour 2 sections

Havelock North 5 sections

Blackhead 4 sections

Abbotsford (Waipawa) 7 sections

Napier (30 acres) 6 sections

29 sections

Before this date Colenso had built on the property where part of his home still is in use as a flat in Colenso Avenue. His land lay between Milton Road and Faraday Street. His first cottage is seen in a sketch of Napier in 1862. It was the only house on the hill top for some years. Advertisements in the Herald tell of progress; on 4.12.58 the public was notified that no longer would there be a common thoroughfare through his property; on 26.7.59 fencing was proceeding round his new building (the cottage); on 14.4.60 the advertisement called for spade labour to clear, dig and fence his three acres about his house. Never in his life did Colenso tolerate unwarranted intrusion on his property because his beloved trees had all too often been wilfully damaged.

Colenso as an owner of property scattered through the Province could exercise a vote in at least five places if he could reach them all during polling hours. From the middle of 1857 when Separation of Hawke’s Bay from Wellington was afoot, he began to take interest in public affairs and he contested several issues. He represented Napier Town on the Provincial Council from its inception.

6.

During his time of service he held one or other of the offices of Provincial Treasurer, Auditor, Secretary, Acting Speaker, School Inspector and Interpreter – also he represented Hawke’s Bay in the General Assembly. He was reported fully whenever he made a speech. The local papers always gave much space in the Correspondence columns also for Colenso was always NEWS.

What a difficult man he was at meetings, a veritable thorn in the flesh. He was a man of quick perception intolerant of humbug and of those who did not respect the law. He was filled with wrath at wrong-doing; his own failures to live up to his ideals tormented him and may have been one of the causes of his temporary withdrawal from his interests in science and even in friendships and driven him to seek offices in which he could not have found pleasure. Yet he was kind and ever ready to help others. This action is typical. Trees were advertised for sale, fruit trees they were. Colenso wrote to the Herald “wishful of helping those desirous of cultivating trees of the fatherland”. His column-long letter told settlers the sorts best adapted to the district and the proper methods of planting. He made special reference to the king of British fruits, the apple, upon which he discoursed, referring to the classics and quoting Virgil, Milton and others. (A volume of the classics was always carried on his journeys).

About 1867 Sir Joseph Hooker’s work “The Flora of New Zealand” was published. Colenso had the honour of being one of the principal contributors. Hooker, now the senior British botanist, paid tribute to his enthusiasm and devotion as a collector saying – “In every respect Mr Colenso is the foremost New Zealand botanical explorer and the one to whom I am the most indebted for specimens and information.”

The first cultural organisation in Napier was the Mechanics Institute. It was promoted in 1858 and secured a grant from the Provincial Council of £300. The request for the use of the reserve in Clive Square was refused. A reading-room was opened in the Masonic Hall in 1863. Two years later the Council granted a site close to the beach. Not one of the three thoroughfares which bounded the site – Browning Street, Herschell Street and Beach Road (Marine Parade) was then formed. The first building was erected in 1865. Though it was little more than a cottage it was named the Atheneum. With extensions it provided a meeting-place and a Reading-room and later a Library for 68 years (1865-1933). An enlargement in 1874 provided a room where temporary natural history displays could be made. Colenso was in the forefront in the nucleus of a Museum.

In 1867 the New Zealand Institute was formed in Wellington. Colenso was a foundation member. In 1864 and 1865 he had prepared two papers for the Dunedin Exhibition. The first was entitled “Geographic and Economic Botany of New Zealand”. The second was on “The origin of the Maori Races”. From the entries ten were chosen for printing – both of Colenso’s being among them. They appeared in Vol. I of

7.

“Transactions of the New Zealand Institute”. From this time Colenso was a constant contributor.

The Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Philosophical Institute was formed on September 4, 1874 at a meeting in the Provincial Chambers, Mr J.D. Ormond, Superintendent of the Province in the Chair. He was elected President and Colenso as Secretary-Treasurer, also as a member of Council.

At this time Colenso was a fully occupied man. In 1872 he was appointed Inspector of the Common and Private Schools under the Provincial Council. At this time there were 18 schools between Wairoa and Te Tamamu, but increase was constant as land was opened up. When the Provincial Councils were abolished in 1876 Colenso continued until 1878 as Inspector of Government Schools. (Initial salary – £150 and £100 travelling allowance annually – both increased to a final salary of £300 and £150 at the end of his service).

Colenso was truly a great pioneer of education in the Province. He made valuable reports on the standard of education and the working conditions. He visited every school for a full day three times a year travelling on horse-back on difficult roads. His heavy clerical work is shown in his letter book. This book also reveals that he was just and kind. In his clear script he would pen a note telling the teacher concerned of new pupils. It might be in these words – “Please receive two little girls, daughters of Mrs Garry, Margaret aged 7, and Mary aged 5 …” – so intimate in comparison with cold forms to be filled in. Colenso was a humane man who saw that each child was treated properly. There was a spate of correspondence between him and a teacher who was betraying the three placed upon her by not acting in the best interests of all the children. He wrote to her saying – …. Our Public Schools are for the children of all settlers, whatever their station in life may be. They are not instituted for the benefit of the teacher, neither for that of the children of the wealthy few, nor of those who are better off than their poorer neighbours and, (as I told you before), even if children come to school poorly clad and without shoes such are not to be ill-used or roughly spoken to, and cannot be turned away …..”

When a well-esteemed lady was retiring from a Trust School in Napier Colenso wrote to the Trustees. He said “….. I do hope you will not elect any applicant who does not possess the necessary fitness – that aptitude to each – without which all other qualifications are certain to be neutralised and further that you will not be led to confer the position upon any decayed gentleman or elderly respectable person maintain because such a one has been highly education and now requires some pecuniary help …..” His letters clearly reveal some of the social and economic history of the period.

In 1878 Colenso at the age of 66 years retired from all official positions and took time to enjoy his home and garden, and to set in order his shells, fossils and herbarium. The New Zealand Institute became his chief link with public life. This is the first mention found of leisure. Soon he returned to botany with all his old

8.

enthusiasm. He often went by rail to Dannevirke and Woodville and lodged there. His solitary figure was often seen as he hunted in the remnants of the great forest – the Seventy Mile Bush. The tangible result was seen in the sketches and specimens which accompanied the papers he read at every Institute meeting in 1879.

Colenso resigned office as secretary of the Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Institute after ten years of honorary service. He was President elect for 1885.

Although Colenso’s early associations with Charles Darwin, Allan Cunningham and Joseph Hooker appear to be his only contacts with notable men of science his own work was such that in 1885 certain Fellows of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Hooker, W.D., and three members of the New Zealand Institute – Dr. Hector, Sir Walter Buller and Sir J.E.J. Von Haast nominated him for election as a Fellow of the Royal Society, a signal honour indeed. He was elected in 1886. His name stands with those of two famous Fellows associated with New Zealand, Captain James Cook and Lord Rutherford but only Colenso had done all the work thus recognised entirely in New Zealand. Moreover it was done when he was without contact with other workers in the same field.

Colenso’s minute of election read thus:

“Fellow of the Linnaean Society, Hon. Secretary of the Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Philosophical Institute, Author of numerous Memoirs on the Botany and Zoology of New Zealand and on the History, Language, Manners and Customs of the Native Race published in the London Journal of Botany, Tasmanian Journal of Science and the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute.

Mr Colenso’s labours as a Naturalist, Philologist and Ethnologist in New Zealand commenced half a century ago and have continued ever since ….”

This year the Council of the Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Institute offered Colenso Life membership.

(A tattered copy of “The Evening News” 16.9.1885 made interesting reference to Colenso and the Atheneum so some of the long report has been fitted in with other happenings of the period)

An important event of 1885 was the provision of improved accommodation in the Atheneum for a second floor was added. The Institute gave £75 towards building costs and agreed to pay £25 annual rental and provide for fuel and light. A report of the first meeting in the new room tells that “the room is a commodious one with lofty walls and is sufficiently well lighted at night by four gas jets while there is plenty of window space for a good light by day. The walls are shelved …… the specimen cases occupy a good deal of the floor space ….. The capacity of the room was well tested between thirty and forty gentlemen and about a dozen ladies being present.

9.

“The President, Mr W. Colenso read portions of a long paper on a recent botanical tour of the Seventy Mile Bush his extracts referring principally to some new cryptogems [cryptogams] (ferns, liverworts and mosses) of which he found in all 59 new species. A number of microscopic mosses elicited his admiration and he remarked that a rich harvest still awaited the sucker for these …. He especially mentioned two new tree ferns found by Mr Hill and handed round samples of the fronds for inspection ….

The interest of the evening however centred on the statements of observations made on a recent eclipse of the sun – Messrs J. Goodall, H. Bryson, R.C. Harding and T. Tanner each gave accounts of their observations, all observed at different points in the Seventy Mile Bush ….”

The room occupied by the Institute was described in detail, the larger room was used for meetings and served also as the Institute’s Museum. A small room was used for the Secretary and for the library which contained some valuable books. These rooms and the Lecture Hall adjoining them were above the Library and Reading Room. The Lecture Hall was a pleasant room, quite a big venture in 1885 for its dimensions were 57ft. x 29ft. And 20ft. high in the centre of the caved ceiling with possibly accommodation for 50 people on the pew like seats. In this Institute room from 1885 until 1898 Colenso read many papers and brought to its Museum many specimens and gifts, gifts which might have been on display tonight but for happenings which he anticipated a few months before his death. He protested strongly that a move from the new rooms of 1885 had been made whereby meetings of the Institute and the Museum collections had been transferred to the Lecture Hall. The cases had been placed round the north, west and east sides, the fourth being occupied by the platform. The library had been put downstairs in the public room. The cupboard was kept locked. Colenso protested because he felt there was no restraint placed on boys and others who come there. (He was right; all the best things were appropriated – taken from this unguarded room. It is a sad story). The Lecture Hall is well remembered by some members who attended in the years just before 1931, remembered as a place for good company and good lectures. As for the Museum collections further pillaging in 1931 left little of any value.

Of New Zealand fauna little will be said. Colenso was not the first to discover moa bones for they were comparatively plentiful in some districts. He is acknowledged to be the first person with sufficient scientific knowledge to investigate the nature of the fossilized bones and make correct deductions therefrom. In a short period he wrote on moths, butterflies, spiders, insects, lizards, the Maori dog etc. His material is considered to be exact and authoritative. One wonders what might have happened had his distinctive qualities been directed into one narrow, deeper channel. Without any special training he, at the age of 72 years, accepted a commission from the New Zealand Government to compile a Maori-English Lexicon which was to be a comprehensive Dictionary of the Maori tongue.

10.

Colenso’s interest in philosophy might have been foreseen after reading his paper of 1865 on “The Origin of the Maori Races”. His reference to dialects attracted the attention of a member of the British Institute who was working on the subject. He, in Europe, could seek the guidance of scholars who had devoted years to the study of philology but Colenso worked alone far from such help yet as the years passed his shelves became filled with manuscript which could have been his life work. A change of Government brought loss of financial support for publication so the Lexicon remained unfinished.

What of the physical aspects of this man? He was slender with broad shoulders and great strength of powers of endurance. The artist Lindauer who portrayed him in 1894 showed a man with a high forehead and keen eyes, full bearded but for a clean shaven chin. His hair hung almost to his shoulders as was then not noticeably behind the current mode. His face even at the age of 83 was not heavily lined. His pictures show a well-dressed man. Lindauer was accounted a good portrait painter. He was commissioned to paint many notabilities of the North Island. Several were on the walls of the Waiapu Cathedral and were destroyed so the Museum portrait of Colenso is a valuable example of Lindauer’s art.

Colenso had the friendship of some leading men of the Province. Of all Europeans he had most influence with the Hawke’s Bay Maoris. They knew him as a staunch friend. The leading rangitira [rangatira] was Te Hapuku. Between him and Colenso was sincere friendship based on mutual respect and trust.

Donald McLean, Chief Land Purchase Commissioner, and Colenso were friendly colleagues in the work of establishing the Province. They differed on the Maori Land question. McLean came often to the Mission Station for advice. “I have every reason to think highly of Mr Colenso as a zealous, conscientious man and an excellent and devoted missionary” he wrote. Of him Colenso said – “McLean was such a straight forward excellent man that I have a great respect for him.”

A friend from the earliest days of European settlement was Henry Stokes Tiffen, Commissioner of Crown Lands and a man of affairs. He and Colenso shared a love of trees and philanthropy.

On the firm basis of shared interest in botany and education was genial, kindly Henry Hill who was for 37 years School Inspector for Hawke’s Bay. They both enjoyed the friendship of a younger man, scholarly William Dinwiddie, the legally trained editor of the Hawke’s Bay Herald. All three were writers, all three were keen members of the Institute.

11.

On 11th May 1896 Colenso offered to give a site for a Napier Museum together with £1,500 on condition that an additional sum of £2,500 be raised by the end of the year. At this time he was President elect for 1897. Time passed – His year of office ended on 14th February 1898. At the Annual Meeting he withdrew the offer for only £163 had been paid in. He was obviously very distressed; he had intended to give his books and collections to Napier. He spoke hotly about it. He said not one wealthy man nor one early settler had contributed. He said he would now give £1,500 to his native town of Penzance. This he did and the interest on this sum still supplies help for the needy under the name of the “Colenso Dole”.

In a further effort to do something for the town Colenso spoken to Mr R.D.D. McLean who told him there was between £700 and £800 held in trust for a statue of other member for his father, Sir Donald McLean. This he was prepared to make up to £1,000 for the Museum. No more was found about this project but McLean Park and the Cairn Memorial tell that the money went in that direction.

During 1898 Colenso attended meetings regularly through a cold winter. Moreover on 10th October 1898 according to the next issue of Transactions W. Colenso, F.R.S., F.L.S. (Lond.) read two papers, one a description of some newly discovered ferns; the other (which had a title that in its verbosity recalled earlier usages) was his last contribution to Transactions after thirty years of faithful striving towards the goal that is named in the title – “A Description of a few more newly discovered Indigenous Plants – being a further Contribution towards the making Known the Botany of New Zealand”. As the Branch went into recess about this time this was Colenso’s last meeting. His vitality and good health did not fail until a short time before his death early in the next year.

The Rev. William Colenso who was born in Penzance, England in 1811, landed in New Zealand in 1834, died in Napier in 1899. He was buried close to the entrance of the first Napier cemetery (on Napier Terrace). Close by were the graves of others who had been leaders in Hawke’s Bay, men with whom he had worked. His old friend, Henry Hill wrote – “The scene … was sad, and withal beautiful. An old man full of years and honours was borne to his last resting place. Yet no wife, no child, no relative was there to mourn his passing.”

Yet Colenso, the philanthropist lives on in his annual benefactions. After the settlement of his estate in 1908 it was revealed that he had remembered the needy such as had found their way to his door in times of stress. He did not forget the school children. A Schedule entitled “The Religious, Charitable and Education Trust” was drawn up. The interest from the investment of specific sums of money was to be used annually as directed to – poor prisoners on their release from gaol; to stranded seamen and strangers; to poor families in the Borough of Napier; to Napier High Schools for special prizes. To the Anglican Church a sum of money was left outright. Changes in social conditions during over half a century have

12.

caused the Trust to be considered by the Court on occasions so the above terms are not exactly the original ones but the intention remains intact. The Trust is administered by the Civic Authority.

Colenso’s intense interest in and anxiety for the Institute (as well as for his collection and for the treasures of a life-time that had not been lost in the fire at the Mission Station) had prompted a codicil to his Will after the failure of his plan for a Museum. The wording reveals much of Colenso, some of whose most cherished friends had predeceased him;

“I give and bequeath to my friend Henry Hill, inspector of Schools, William Isaac Spencer, Surgeon, and J.W. Carlile, Solicitor, all of Napier Esquires in trust for the Hawke’s Bay Philosophical Institute the sum of £200 for the common benefit of Library and Museum of the said Society, and also to them in trust for the said Society all my dried plants in bundles and in boxes (roughly put up as they are now), all my zoological wet natural history specimens; my large framed and glazed portrait of my friend, Sir J.D. Hooker, my framed and glazed portrait of my earliest botanical friend, Allan Cunningham, a large coloured photograph of myself (by Carnell) the last to be framed and glazed at my expense (if not already done so by me) before handed over and my framed drawing of my ancient Tamil bell: Provided always that if the said Society shall have ceased to exist or should have fallen in the estimation of those my appointed Legatees in trust, into a state of inanition, that then in such case this devise shall wholly fail and be of none effect as if it were not made.”

The bequest from Colenso to the Branch of the Institute was discussed at the first meeting in 1899. The Council decided to place the sum of £75 on fixed deposit and to spend the remainder of the £200 legacy on a first class lantern and a microscope. A resolution was passed – “that this Branch …. place on record the great loss it has sustained by the death of the Rev. William Colenso, F.R.S., F.L.S (Lond.) who from the foundation was closely associated with the Society as Secretary, member of Council and President and as a contributor of papers on botany, anthropology, and kindred subjects for the advancement of science throughout the world.”

At the first meeting in 1899 of the New Zealand Institute the Director, Sir James Hector, M.D., F.R.S. said he and Mr Colenso had been friends for thirty-five years …. Mr Colenso had been a constant contributor to the work of the Institute ….. He contributed articles of the greatest value upon almost every branch of natural science He did valuable work as an explorer in the early days of settlement … and good work as a recorder in zoological science. But above all things he expended the knowledge of botany in New Zealand. No one who turned over the pages of Hooker’s “Flora of New Zealand” could fail to see what a master mind was his, and what a master hand he had in collecting accurate knowledge in Natural Science.

13.

But these were by-paths in comparison with his great work in philology. He spoke of the New Testament and of how he with his own hands composed, printed and bound it in 1837 and how in addition he carried on a very large charitable work among the Maoris. But above all his mind was for many years almost solely devoted to the collection of the great treasures of knowledge that were “buried” in the languages of Polynesia and particularly to the tracing out of the words involved in the Maori tongue. For many years he has been collecting and arranging and preparing a lexicon of the Maori language and the cognate languages of Polynesia. In every way he had displayed a most liberal mind and he left behind him an influence for good.

Colenso’s home has always been of interest yet it has been quite difficult to separate fact from fancy. His home at Waitangi was lost by fire before there was a Napier but its unusual form became attributed to his Napier home.

From about 1856 or 1857 Colenso owned land on the hill which now bears his name. As it was a flattish hill the land fell steeply into Milton Road and Faraday Street. He owned 30 acres. He built the first section of his home in 1868 and fenced in 3 acres for a garden and orchard. He planted native and exotic trees and shrubs which soon screened the place from public view. This, combined with Colenso’s determined efforts against marauders, gave an aura of mystery to what was really a lovely garden. Older residents still tell of the rare plants and the well tended fern house. Only recently olive trees and myrtles were uprooted to make way for still another house in Colenso’s garden. A few years ago a 170 foot high pine tree near the southern boundary provided for many a winter fire. Some of his trees are still there where he tended them.

Colenso’s home for a few years was in a one gable portion in style similar to the larger portion built later. It is said to have been two rooms and an attic. Later it was attached to the new larger portion by a glassed-in passage about 10ft. x 6ft. and it became the kitchen and store room of his home for many years. It is still on the same site now used as a flat, but is altered by an added room. It was the first house on the hill in 1858.

Colenso’s home as seen in 1894 photograph was attractive, with Victorian comforts but not the over-ornateness of the period. It was set about with garden and shrubs. The photograph, being taken from the southern corner, does not show the space between the two parts.

When Colenso died in 1899 his property was divided into building sections and sold. Mr Plowman bought the land on which the house stood. He took down the main part of the house, left the floor intact, lifted it on to new piles and erected a large house. He used both the old and some new material. Four of the large windows, each with six rows of four panes of glass, were used on the western side and the front door with its large lock and key and the original floor which still shows the marks of

14.

the dividing walls are about all that can be identified as Colenso’s. The house erected in 1901 is now an apartment house and is in no way reminiscent of the home that once was there. In 1931 one prized property of Colenso’s, his never failing well, was heard to empty immediately after the great upthrust of the land. It is now filled in. The 30 acre property too is filled for many homes have been built on it.

In this paper Colenso’s words have often been used and those of his intimate friends and colleagues for nothing else could so clearly reveal his qualities to those who seek to know of him. At times reading of his life brings a dim sense of the magnitude of his search in the far distant past – a past beyond the time computed from Polynesian genealogies of the early occupiers of this land – his search into many aspects of the Polynesian people that might also bring an answer to the whys and wherefores of New Zealand’s rare flora and fauna. Modern nuclear science, undreamed of in his time, may show Colenso to be a man ahead of his time, gifted beyond the comprehension of most of his generation.

It is open to question in which field Colenso accomplished his best work – this master of many crafts and branches of science, this man whose reputation extended beyond the Antipodes. Unwittingly the Church Missionary Society sent to New Zealand a great man but failed to continue to use him to the best advantage, but Colenso continued to help the Maori people, to succour the needy, to further justice in the land of his adoption and to serve the Lord.

Paper compiled – by Aileen M. Andersen, M.B.E.

H.B. and E.C. Art Society – 1961

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Subjects

Tags

Format of the original

Typed documentDate published

1961Creator / Author

- Aileen M Andersen

People

- H Bryson

- Sir Walter Buller

- J W Carlile

- Carnell

- William Colenso

- Allan Cunningham

- William Dinwiddie

- Lady Jane and Sir John Franklin

- Margaret, Mary and Mrs Garry

- J Goodall

- Copeland Harding

- R C Harding

- Sir James Hector

- Henry Hill

- Governor Hobson

- Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

- Sir William Hooker

- Lindauer

- Sir Donald McLean

- R D D McLean

- J D Ormond

- William Isaac Spencer

- T Tanner

- Henry Stokes Tiffen

- Sir J E E Von Haast

- Reverend Samuel Williams

- Messrs Plowman, Wade

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.