- Home

- Collections

- VOGTHERR GE

- I Too Have No Regrets

I Too Have No Regrets

Contents

Introduction 4

Dedication 4

My Childhood and Family Memories 5

My Sporting Memories 18

My Schooling Memories 24

My Working Memories 24

My Earlier Motoring Memories 28

My Aeronautical Memories 37

My Adult and Matrimonial Memories 40

My Later Motoring Memories 53

My Tourist Memories 68

My Great Race Memories 82

My Final Motoring Memories 92

My Later Memories 118

My Battlefield Memories 123

My Memories of Friends and Inspirations 125

My Early Karamu Road Memories 128

I Too Have No Regrets 3

My Childhood and Family Memories

My parents were married on 7 November 1923, by Canon Hall at the St. Matthews Anglican Church, in Hastings. My father was a 25 year old pork curer Ernest George Frederick Vogtherr and my mother Doris Ridgway Corbin. My mother was very level-headed and had meticulous accounting skills. They had a house built by Mr. Adamson at 707 St. Aubyn Street West, near the intersection with Grays Road. I came into this world on Monday, October 26, 1925. I was born at Sister Julia Fahey’s Private Maternity Home at 201 Grays Road, Hastings and as it turned out, I was to be an only child.

My father was born in the age of the horse, but brilliant engineers were beginning to perfect the internal-combustion engine and petrol driven vehicles were becoming a fascinating novelty. His earliest experience of petrol driven vehicles was riding occasionally on commuter buses.

My paternal grandfather Carl and his family of five had emigrated to New Zealand half way through 1913. There was his wife Sophia, three sons Ernest (16), Leonard (9) and Carl junior (6) and an only daughter Winifred (14). Carl senior had been born Friedrich Wilheim [Wilhelm] Karl Vogtherr in the town of Blaufelden, Germany on August 9, 1873. Blaufelden is town in the Baden-Wurttemburg region midway between Mannheim and Nurnberg. His parents were Johann Friedrich Vogtherr and Margaretha Barbara Martin.

Karl completed his schooling in Germany when he was 12½ years old. He was sent to live with relations in the North-East of England as a 14 year old. The family were led to believe it was to avoid military training and the ambitions of the ’iron chancellor’ Bismarck, and probably was prompted by his great-grandfather‘s decision in desert the Royal Prussian Infantry. Thus, as a fugitive traitor in 1804, he was destined to never see his wife and children again. More likely Karl’s move to England was the result of the industrial revolution, when England became a major land of the opportunity. The German butchers had become admired and their sausages had an outstanding reputation. The German immigrants of the middle of the 19th. century found it easy to establish a successful butchery business. Nearly all the butchers came from the small Hohenlohe district of Baden-Wurttemburg. This improvised agricultural area is only 30 miles in radius in the north-eastern of the former kingdom.

Karl was employed in the uncle’s big butchery and small goods shop in Sunderland. This was at 15 North Bridge Street in the Wearmouth section of the city. In the 1891 census, 23 year old pork butcher Ernest Martin and his English born wife Maria, were employing three Germans in the butchery. 24 year old John Saham was the assistant pork butcher, while 19 year old Friederich Keith and Karl were the apprentice pork butchers. All came from the same area of Germany as Karl. They all lived above the shop, along with two young English domestic servants. At the time, Karl Hanselmann from Blaufelden, had a pork butcher’s shop at 21 North Bridge Street. His younger brother Gustav had owned a butcher’s shop at 260 High Street.

After coming out of his apprenticeship, Karl took over the ownership of the business from his young uncle who was immigrating with his young family. Karl sold the shop and moved to a better location only a few blocks away. This butcher’s shop was at 264 High Street and he had fifteen people serving behind the counter. He lived above the shop as did most of the employees. He anglicized his name to Carl William Frederick Vogtherr, just prior to his marriage. He only had a very basic standard of English.

In the 1901 census he was employing four German immigrant lads, 21 year old Fred Schoch was a shop assistant, while 24 year old John Haln, 19 year old Gottlab Alldorfer and 18 year old Conrad Schmitz were all pork butchers. He also employed four German woman. 23 year old Barbara Manion was a shop assistant, while 35 year old Caroline Martin from Blaufelden was the domestic cook and she was an aunt, the sister of Ernest and Fred. Two German teenagers Maggie Buetshewort and Caroline Henne were domestic servants, along with local girl Hetty Snowball who was the housemaid.

Unfortunately during 1902, aged only 29, Carl suffered ill health and was forced into temporary retirement. He took his family to live in a small village called Cleadon, four miles north of Sunderland. Here he purchased a nice new brick villa on Whitburn Road, which he called Sunny Brae, after a Collie Club in Illinois. Carl was already breeding top class Rough Coated Collies and exporting them around the world. Until his health returned he concentrated on breeding and showing his dogs, plus numerous varies of fowls and racing pigeons. Karl was the judge of the sheep dog section at the International Dog Show at Berlin in 1907.

In a short period, he purchased several cottages in Chester Street, Sunderland which bought in a steady rental income. One of these was a Victorian Terrace house at 6 The Westlands, which was on the south side of Chester Street, forming part of the West High Barnes Estate. Carl mortgaged this property in April 1903 for £400. He on sold this property to a leading pork butcher George Bruck in June 1907.

The North-East was always very impoverished and in 1909 the Great Slump, a minor worldwide economic panic had put many out of work, and rents from the cottages dried

Photo caption – Carl Vogtherr

I Too Have No Regrets 5

up. Carl’s health had improved sufficiently for him to begin working again. He sold Sunny Brae, after turning one of the Chester Road cottages into a beautiful double fronted pork and beef butcher’s shop, with marble interior and several mirrors. At the time, there were 16 butcher’s shops on Chester Road. The family moved to one of their rented properties in High Barnes in the West end of Sunderland. Eventually financial issues forced them to shift into the upper storey, above the shop.

Carl opened another small branch in High Street, opposite the Empire Theatre, where you could see a silent movie for four pence from the ‘gods’. The economic slump worsened and business declined. Carl was forced to close both shops. In 1911 Carl leased a butchery’s shop at 36 King Street, South Shields, nine miles north of Sunderland. The 1911 census records Sophia helping in the shop, while Carl was employing another four German immigrants. 29 year old Fred Hafele was a journeyman pork butcher, while Albert Martin was still an apprentice pork butcher. Two women, Annie Harchtel and Rose Sahm were the domestic servants. This venture was a total disaster and the family were forced to sell all their furniture, his wife’s engagement ring and many presents from their wedding twelve years earlier.

Always the optimist, in 1912 Carl took over a butcher’s shop in Merrington Lane, a suburb of Spennymoor, 20 miles south of Sunderland. Opposite the shop was the large M. Coulson & Co. steelworks and close by a huge coal mine employing three thousand men. Within months the men at the Iron and Steel Works went on strike. After a month, the owners closed the business and transferred the work to another plant in Middleborough. Surprisingly my paternal grandfather’s business still prospered even after the steelworks closed.

Out of the blue he received a cablegram from his 56 year old uncle in New Zealand. Friedrich Martin was born in Erpfersweiler, five kilometres north-west of Blaufelden, Baden-Wurttemburg and after emigrating in 1874, he had become a naturalised New Zealander in 1882. He commenced two pork butcher’s shops in partnership with Johann Kuch in Wellington in 1882. One was at 59 Willis Street and the other at 153 Cuba Street. Although the partnership dissolved within 12 months, Fred kept operating in Willis Street for 25 years.

Fred Martin purchased the troubled Palmerston North Mild Cure Bacon Company in Grey Street in November 1907. He began providing Kiwi Bacon and Ham products. He killed up to 100 pigs a week. Now in 1913, he wished to retire as his health was not the best. He offered to pay the family’s fare to New Zealand and give Carl a half share of the business. The company was making a £3,000 annual profit. Surprisingly my paternal grandfather was going to turn it down, as emigrating was considered a gesture of failure. But his wife was having none of it and after a flaming row, Carl had to accept the challenge. The Merrington Lane shop was sold to a mean Yorkshireman.

On their last day in England the family took a Red Bus ride around the traffic jammed streets of central London, to see the famous sights. All my father remembers is fog, and his eyes stinging from all the petrol flumes. The family departed from London, as second-class saloon passengers aboard the New Zealand Shipping Company’s R.M.S. Ruapehu, under the command of Captain Greenwood on March 13. For the voyage, they were in pairs in three separate cabins. They experienced strong winds in the channel before arriving in Plymouth. They continued their voyage at 2 pm on March 15. The ship encountered a fresh south-west gale and heavy seas across the Bay of Biscay, to reach Teneriffe [Tenerife] on March 21. They sailed at noon the same day, and they had fine weather accompanied by moderate trade winds all the way down the Atlantic Ocean to Cape Town on April 5.

After only a four-hour stopover they were sailing across the Southern Ocean. The vessel immediately encountered one short violent westerly gale, with waves higher than the vessel, but otherwise they were blessed with favourable conditions. The R.M.S. Ruapehu berthed in Hobart on April 25, to unload a few passengers and 690 tons of general cargo. For the first time, they were allowed to leave the ship and have a few days on dry land.

There was trouble in Hobart, when a young Irish passenger Jimmy Duffy got inebriated and took on the whole bar, assaulted the bosun and finally the quartermaster back at the ship. The trouble maker ended up facing the local magistrate and four months gaol.

The family commenced the final leg of their voyage at 8 am on April 28. Across the Tasman Sea, they experienced south-west gales and monstrous seas. The captain would not risk bringing the vessel into Wellington in the dark, so they attempted to shelter in Cloudy Bay. Unfortunately, the wind changed to the south-east, bringing heavy squalls. Therefore, the Captain R. C. Clifford had to hove-to, and the ship spent the night in Cook Strait, until daybreak.

Early on Saturday May 3, the vessel came through the heads into Port Nicholson and anchored in stream at 8.30 am. After pratique had been granted by the Port Health Officer, the Ruapehu berthed at the King’s Wharf at 10.20 am. After a 52 day voyage, Carl Vogtherr brought his family down the gangway on to the land of promise.

Fred Martin’s wife Elizabeth met them at the wharf and took them by train to Palmerston North. They were surprised, the business situated at 12 Grey Street, opposite the Dalgety sale-yards was not a sophisticated

Photo caption – Dominion. 3 May 1913. Carl and his family arrive in Wellington, New Zealand.

I Too Have No Regrets 6

operation, but a small shed, and a small cool chamber refrigerated by a gas engine. My father started on 15 shillings a week, but his father would grab 12s. 6d. of this. Within six months he was earning 30/- a week.

The Vogtherr family lived at 12 Grey Street next to the bacon factory, before finding a large house in Frederick Street. They quickly moved on to another home in Campbell Street. In May 1914, Ernest Hansel an employee asked for the opportunity to purchase the business. Fred Martin agreed, believing Ernest wouldn’t find the finances, but he did and the offer had to be accepted. As compensation for losing the promised takeover agreement with his uncle, my grandfather Carl Vogtherr was paid a sum of £1000 by Hansel, with the understanding that he would not start in opposition, within 25 miles of Palmerston North for five years.

My grandfather bought a Hastings ham and bacon business in July 1914 from Walter Kessell and commenced setting up his business. Kessell a restaurant cook had purchased the Dainticure Bacon Company in June 1909, from William E.S.Wood. The factory and cool store was at 607 Miller Street and Kessell opened a shop on the corner of Heretaunga Street and Station Street, previously the site of H.J.Webber’s pharmacy. The Lowe Brothers Butchery took over the shop in December 1912, as their town shop. Walter Kessell operated out of Alfred Rebay’s old pork butchery location at 111 Heretaunga Street East, near the Grand Hotel. This was where my grandfather Carl Vogtherr set up the new Elite Ham and Bacon Company.

The property was owned by the chemist Herbert Knight. The premises were in a prime location, but not very desirable. It was a long but not very wide, producing a cramped work space. It had a 14 foot frontage and was 60 foot long. At the rear was a smaller room, 10 feet by 12 feet which had a right of way leading from Karamu Road. The ‘Elite’ delicatessen opened its doors for business, on the day the Empire declared war on Germany, August 4, 1914. The family lived on the second floor above the premises.

Carl originally offered 14 different products but found it didn’t work. He struggled to sell his classic types of German Bratwurst to the locals. Thereafter, he whittled it down to around four items. People wanted to eat bacon, so he advertised in the local paper for pigs and switched his focus to bacon and ham. He would kill and cut up the pigs in the back room of the store. The best pigs were female about nine months old. He hired cool chambers in the newly built Hawke’s Bay Fruit and Produce cool stores, on the corner of King Street and St. Aubyn Street. Working in the cool store office was a 14 year old boy named James Wattie and also a young blonde lassie named Doris Corbin.

Here in the cool chambers, my grandfather created a brine from hand-mixed curing ingredients including salt. The meat was put in the brine and left to cure. This would take seven days in the cool store at 1°-3° C. After removing the meat from the brine, it was washed with warm water then left to dry in a cool airy place for two days. Next it was lightly smoked for about 30 minutes with the smoke temperature no higher than 42° C. Oak and beech produced the best results. He would mature the ham and bacon by dry stacking or hanging the product, and drying it with a light air flow. This made it special and the slow method produced a quality product,

I Too Have No Regrets 7

ready for sale after eight weeks. The two styles of smoked hams were Westphalian and Kassler.

Meanwhile Ernest Hansel had offered my father, £3 a week and free board in the vacated Martin home next to the factory, as an incentive to stay on at the Palmerston North bacon factory. Six weeks later, my grandfather needed his assistance, so he followed the family to Hastings. Carl also employed Joseph Smith, who had been working at the Kiwi Bacon factory.

My grandfather’s business thrived, purchasing up to 100 pigs a week and providing rolls of ham and bacon for local stores, restaurants and families. The delicatessen would hand slice up to 60 cooked hams every week. A smoked cured pig’s head sat in the shop window for decades. This was novel way of advertising and a great attraction for young children, out shopping with their mothers.

Unfortunately during the war, the family were persecuted, because of our German surname, but friends, notably W. Richmond, assisted my grandfather to continue in business. It probably didn’t help that the outspoken Socialist in the Reichstag at the time was named Vogtherr. It wasn’t an ideal start for a German pork butcher and wasn’t helped when the Post Office Savings Bank froze his account with a tidy nestle [nest] egg.

My grandfather had to register with the police and other personal complications arose, such as the manager of a bank who turned down a cheque without even ringing up. My father meanwhile had several hundred pounds in his pocket ready for banking, so he quickly switched to become a customer of the National Bank. One local bacon company in direct competition tried dirty tactics, with a placard in the window, ‘Buy from the British firm‘, surmounted on the Union Jack. My grandfather’s business prospered because of his superior product and it went full circle, with this firm asking him to buy them out.

The hatred towards German people climaxed on the New Year Eve attack on a pork butchery in Gisborne. A crowd of about 2,000 people demonstrated outside the shop after sunset and culminated in throwing stones and bottles at the windows. The police were unable to halt the violence until the crowd dispersed about 2 am. Friedrich Wohnsiedler was born in Mulfingen, Baden-Wurttemberg and later became a pioneering figure in the winemaking industry in New Zealand. Similarly, C.Heinhold’s pork butchery in Wanganui was stoned and looted in May 1915. During this period, many Germans were sent for internment on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour, for the duration of the war.

The anti-German sentiment came to a head in Hastings, after the Gisborne reprisals. In the wake of the sinking of the Lusitania and the first usage of poisonous gas, a patriotic meeting organised by the local Liberal MP Dr. Robert McNab was held in the Princes Theatre on the night of May 17. Hogan, a tough police sergeant, was determined to stop any hooliganism. He organised a number of reliable citizens and mobilised the Legion of Frontiersmen. Meanwhile my father and his brothers set up kerosene tins as warning devices in the backyard of the shop and all night they sat outside and waited for the worst. A mob assembled in Heretaunga Street ready to cause havoc but eventually melted away, after seeing Hogan and his reinforcements of Legion of Frontiersmen in uniform. Afterwards the family had no further bother and people accepted them as equals.

Archie Lowe had commenced a butchery delivery in 1910 and was soon joined by his brother George, who owned land at Stortford Lodge on the corner of Maraekakaho Road and Omahu Road. They built a brick building

Photo captions –

Hawke’s Bay Fruit and Produce cool stores.

Downstairs boarded up, upstairs windows smashed.

I Too Have No Regrets 8

for fruit cool stores and a butchery. It had a sturdy oak outside the front entrance. The refrigeration unit was powered by a 35hp Trangye gas engine supplied by a gas plant and using an ammonia compressor pump. They had an ice making plant, producing 2¼ tons per day.

In September 1913, the Frimley Fruit Canning Factory had closed because of bad management. Therefore, late in 1914, part of the Frimley factory was relocated by the Lowe brothers on to their property at the Stortford Lodge intersection, to become the Stortford Lodge Bacon Company on Omahu Road. On the adjacent corner of the intersection was the Stortford Lodge Hotel and on the opposite corner Lynch’s Grocery store.

In early December 1916, my grandfather’s chief opposition the Lowe Brothers asked him if he would like to purchase the Stortford Lodge Bacon Company. The purchase price was less than the rent he was paying for the cool chambers. Part of the contract included the Lowe Brothers supplying the steam and refrigeration. On the same day the deal was signed, the Hawke’s Bay Fruit and Produce cool stores announced a rental increase. Carl moved all his stock to Stortford Lodge and commencing killing there on January 8, 1917. On Friday night April 27, the King Street cool stores were razed to the ground, in a massive fire which lit up the night sky, and the cool stores were never rebuilt.

My paternal grandfather renamed the Stortford Lodge factory the ‘Elite’ Ham and Bacon factory. The new premises were well equipped. Unfortunately, when they moved to Stortford Lodge the factory was full of mouldy unsold bacon and infested with bacon flies which took years to eradicate. My father ran the wholesale side at Stortford Lodge and my grandfather the retail side of the operation. The steam posed no problems but the refrigeration plant, using an ammonia refrigerant, struggled to supply the capacity to cool the bacon factory, fruit cool stores and ice plant, especially during the peak period December to April. Any variation in temperature was detrimental to the meat products.

The move to Stortford Lodge brought Elite into direct competition with the established firms. My grandfather now doubled his weekly kill to 200 pigs. The family and business had a postal box No. 266 and now had two phone numbers as seen in the photo.

In 1918, my grandfather purchased the whole of the Lowe’s enterprise, incorporating the butcher shop, the brick fruit cool stores and the ice plant for £2500. At the time aliens were not allowed to own property in New Zealand. The purchase was achieved through the mortgagee William Richmond holding the lieu over the property. Richmond’s very successful meat exporting business made him a powerful figure and he backed my grandfather’s endeavours.

With control over the whole enterprise, improvements were made. They gained a connection to the borough sewer system. They replaced the old gas engine running the refrigeration unit, with electric motors. My father quickly learnt how to run the refrigeration plant and all about fruit cool storage. During the season the cool stores held 40,000 cases for the local orchardists.

The staff employed at Stortford Lodge included Bill Napier the engineer, Jack Kelly, David Graham the office clerk, Bill Marven, Jack Kelt, Frank Wharton, storeman Bill Wilkins and Jack McCormack, who was a bacon curer in the factory for 17 years.

My father’s first adventures in motoring began by purchasing a second hand ‘Governor’ lightweight two stroke motorcycle in 1918. This bike provided one 14 mile push home and his first brush with the local constabulary. He sold the ‘Governor’ to purchase a B.S.A. for £12. This motorcycle had survived the H.B. Fruit and Produce cool store fire in April 1917. It didn’t last long. In avoiding a head-on collision with a cyclist on the wrong side of the road, Dad ended in a ditch and his motorcycle was left a little dented. Soon afterwards he sold the B.S.A, and began looking for a safer alternative. He was banking £4 every week from his £4.10s wages.

Photo captions –

Stortford Lodge butchery & cool stores. Bacon factory far right.

Elite Bacon Factory, Stortford Lodge.

I Too Have No Regrets 9

In 1923 new bylaws were introduced, making Nelson’s (NZ) Ltd at Tomoana, the only licensed abattoir in the borough. This instigated increased killing costs as the factory could no longer kill the pigs themselves. Up to this stage they had used a horse and cart for transporting to and from the Stortford Lodge factory. Bill Hyslop a salesman from Tourist Motor Company called one day to demonstrate the latest light truck to my grandfather. It was the very first Chevrolet truck to be sold in Hawke’s Bay. My father learnt to drive it that morning. In the afternoon, my father was entrusted with the 1924 ’Grasshopper’, to collect a load of frozen pigs from Tomoana. This included a tricky backing manoeuvre down a long tunnel. This model’s nickname ‘Grasshopper’ came from the characteristic sudden jump when engaging of the clutch. This truck was used for the ‘Elite’ Bacon Company’s pick-ups and customer deliveries for the next 14 years. About 1924, Heretaunga Street East was renumbered and the Elite delicatessen address became 128 Heretaunga Street East.

On May 8, 1925, my paternal grandfather became a naturalised New Zealander, thus gaining the rights to vote and old age pensions. For many years, the family continued breeding Rough Coated Collies and in 1926 my father won the champion puppy trophy with Sunny Brae Sentinel. The family had carried on the same stud name from Sunderland. In 1925, my father started breeding himself, after buying a black Collie bitch ‘Lassie’ from a saddler Bill Carberry, who lived in Grays Road. His father Carl wanted the first choice of the original litter, and this puppy registered as Champion Stortford Jack became one of the most successful prize winners in New Zealand between the two world wars. Lassie’s pups paid for my father’s first car.

My parents were engaged just prior to Christmas in 1922. My mother’s parents lived at 522 Grove Road. The Hastings Borough Council had just introduced a scheme, where they would lend up to £750 to home builders, at 5% over 25 years. The applicants had to have a fully paid freehold section. My parents found a section in early 1923 in St. Aubyn Street west and paid Billy Beale £175.10s for it. The Hastings Borough approved the building tender from prominent constructor Jimmy Adamson, who put Ted Wall in charge, with Billy Weaver as the carpenter and Billy Beale the painter and decorator. Bad weather delayed construction but the house was ready for my parent’s return from their honeymoon.

In 1925, my father purchased his first car, a 1912 Hillman 12hp roadster for £50. It was a three seater and had huge brass headlights lit by acetylene from a cylinder on the running board. Strangely appropriate, during the evening prior to Labour Day, my mother began having contractions, so was escorted to the maternity home. I was born about 8 am on Labour Day. When it was time for my mother to take me home, my father had to pay £12.12s to Sister Fahey for the pleasure. My father named me Gordon in honour of the then Prime Minister Joseph Gordon Coates.

Soon afterwards, my father had biked home from Stortford Lodge to have lunch, when his mother rung to say his father had been involved in an accident at the bacon factory. He rushed back and found his father smothered in blood. Dr. Harry Wilson was called and Carl Vogtherr was immediately whisked off to Royston Hospital at 207 Avenue Road West. While oiling parts of the revolving shaft, he had failed to turn it off, and was hit in the head by a moving part. Knocked unconscious, he fell on to the revolving shaft, which gripped his apron. It twisted tighter and tighter until it began ripping skin and flesh from his stomach. On coming to, he had released himself from the belt and phoned for help. Carl was in hospital and off work for a long period and Dad ran the whole Stortford Lodge operation. My uncle Len was employed to handle the books and invoicing. He demanded £5 a week, while my father was only getting £3.

My mother told me that I was a little monkey and wouldn’t sleep. The chemist Herbert Knight prescribed a Plunket Society diet. To stop me crying as a baby, she would carry me outside and put me in the car, and Dad would start up the car engine of his new 1926 Chevrolet Tourer. Instantly the crying would cease. My father said to make me sleep, they parked the car outside my bedroom window with the motor running. Immediately I would relax and nod off. As benzine was 1s. 9d. per gallon, it was a cheap method of sedation. Therefore, it will surprise no one, that the first word I spoke was “car”. Someone once said, “Give me the child until he is seven and I will show you the man.” With me it was probably just seven months. Petrol was obviously in my veins.

I had more than my share of ailments as a child. I was in and out of Royston Hospital on numerous occasions, before I reached five years of age. At the time, the hospital was a two storey building in Avenue Road West. I encountered a series of ear problems, stomach disorders and nose complaints. Not helped by falling down the backstairs at home before I was two years old, and breaking my nose. Another illness occurred after riding on my father’s back in the Tuki Tuki River and swallowing some scummy water. I got terrible diarrhoea, and Dr. Harry Wilson admitted me to the hospital. I eventually recovered, but on the day I was to be released, there were complications. At 11 am, Royston Hospital rang the bacon factory and told my father I urgently needed a blood transfusion. My father rushed into town and gave the blood. It did the trick and I was allowed home that night. Unfortunately, two weeks later I had a relapse and was again in Royston Hospital.

I had ear problems and Dr. Harry Wilson was reluctant to do several incisions inside my ears but recommended a Napier specialist. My father wasn’t impressed with the £21 bill, and Dr. Wilson had it reduced to £10. A few years on, I attended a kindergarten adjoining Royston Hospital. About this time, we purchased our first radio. My father gave up smoking and stopped attending race meetings. Hence his money went further. Furthermore, Betty a lovely Rough Coated Collie became my playmate, whether she liked it or not. I used to lead her around by pulling her mane.

During 1928, my grandfather gave notice to the butcher shop tenants at Stortford Lodge to start looking for new premises, as he wished to turn the corner location into a petrol bowser station. Immediately the word spread,

I Too Have No Regrets 10

two fuel companies signed a supply agreement, after my grandfather paid a £10 deposit. My grandfather spent £600 on alterations to the building, while the petrol companies insured the supply of the pumps and oil cabinets. Both these oil companies failed to deliver. Eventually my grandfather was operating a petrol station on the corner selling Plume Motor Spirit, Big Tree and Union petroleum brands. The bowser station had two large metal concertina gates that my father opened and closed every day. Eventually the service station had seven pumps, three owned by Atlantic Union Oil, another one supplying Shell Petroleum and another Vacuum Oil Company. The other two were owned by my grandfather himself.

When my grandfather returned to work after his long convalescence, he was belligerent and very difficult. My father knew a showdown was imminent. Dad took a Saturday afternoon off work. He took Mum and I across to Nelson Park, Napier to watch Hawke’s Bay play the touring English cricketers on a glorious summer’s day. The illustrious visitors plundered 511 runs off the local attack. That day February 1, 1930 my grandfather and Uncle Len had a huge ’barney’ and my uncle had walked out on his father. Fifteen years later Len would be national secretary of Meat Producers‘ Association.

Six weeks later, my grandfather employed a new man in the office. Immediately the books would not balance. Finally, my father had some evidence that dishonestly was before the shortfalls. My grandfather abused my father for even suggesting the new man was stealing. This was in October 1930, and my father just walked away from the factory and the family business. During the Depression, it wasn’t easy to find paid employment and he quickly encountered the difficulties involved. He started hay baling before spending several weeks digging out weeds along the railway siding for the Atlantic Union Oil Company. They liked his ethics so kept him on, to fill four-gallon tins of oil. He then spent a week driving a truck for Alex Wilkie, for £5.

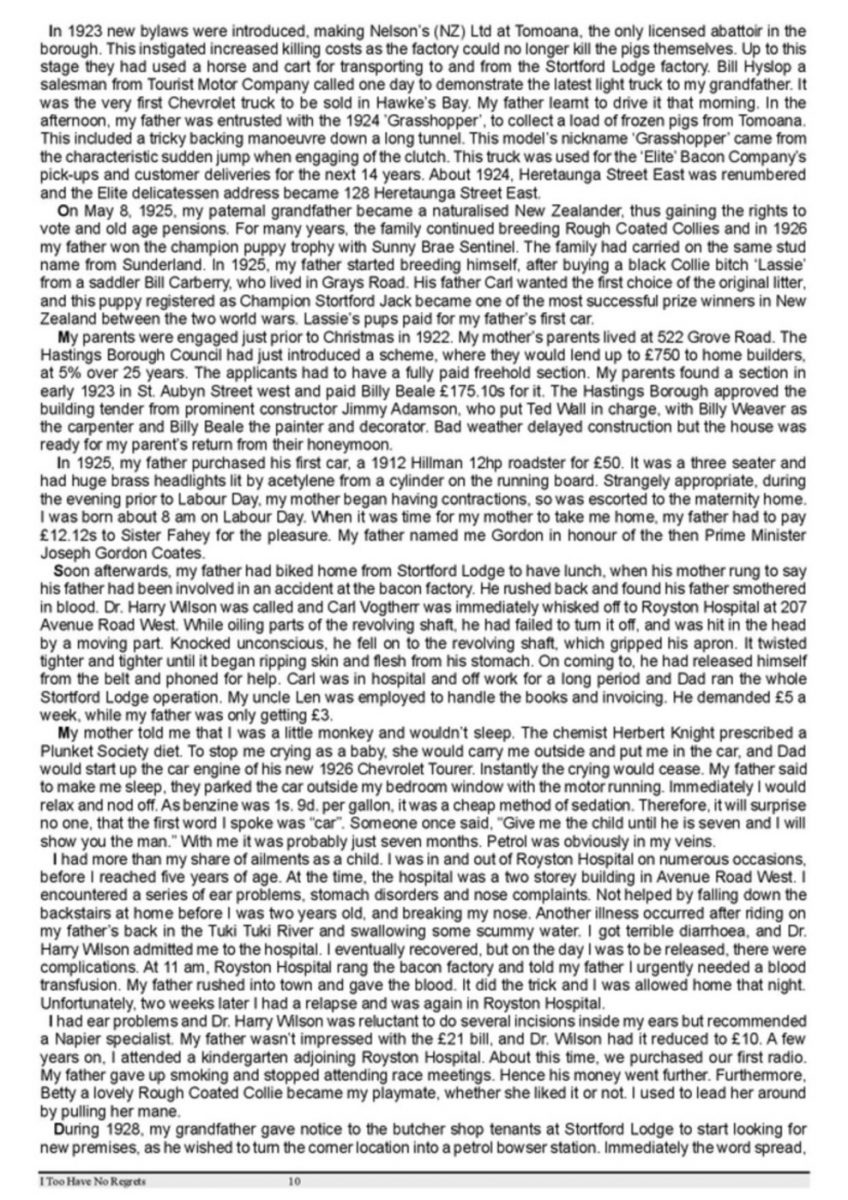

During November, a vacancy for a manager for a new bacon factory opening in Nelson, appeared in the Situations Vacant column in the Dominion newspaper. They received 26 applicants but my father was the only one the Department of Agriculture would recommend. The owner, a broad spoken Scot with a wooden leg arrived at our door wishing to talk to Dad in mid-December. James Wyllie had been born on Blackbyre Farm, east of the village of Fenwick in Ayrshire during 1884. His family still resided on the farm but he had taken over Kershaw Engineering in Nelson. He enlisted during the war and became a Lance Corporal in the NZ Engineers. Eleven months after arriving in Europe he was admitted to a Casualty Clearing Station in the Le Touquet sub sector, suffering from gunshot wounds. He had a fractured right humerus and a severe foot wound. His right leg was amputated above the ankle. He spent 19 months in hospital, in which time he designed two artificial limbs, which were manufactured and supplied in June 1918. These were eventually damaged in New Zealand and he made new artificial legs himself at his engineering works. Wyllie’s first wife had just died and in the near future he was to marry his children’s housekeeper.

Wyllie had been left £3,000 by his mother in her Will and wished to invest in a new venture. He assured my father he wouldn’t interfere in the running of the bacon factory. My father’s first impressions of Wyllie weren’t good. He appeared to be combative but offered to pay for Dad to travel to Nelson to look at the prospective operation. The following Monday, Dad sailed across to Nelson, on the Arahura. They went out to Appleby, where an old Cider factory was to be the proposed bacon factory. It was a converted coolstore on the Nelson-Motueka Road. It had no water supply, two large soakage pits for drainage, generator power, coal fired refrigeration but had plenty of steam. The killing would take place on site. My father suggested to James Wyllie to forget about this enterprise and left Nelson thinking he had persuaded him against further progress.

Just before Christmas, Dad began selling Electrolux refrigerators for the Hastings branch of the Napier Gas Company on commission. He was one of 126 applicants, and got the job because he was the only one with refrigeration experience. On his first day, he sold a big unit to Charlie Slater for his fruit storage and received £8.10s in commission. On the second day, he sold another refrigerator. That was the last sale he was to make. Door knocking at hundreds of homes produced the same result. No one had any money and my father was not making any. So, he handed in a fortnights notice. Roach’s Department Store promised to put in five fridges but that was a future project. During Monday February 2, my father had met with the former mayor George Ebbett and measured the kitchen in their Southland Road home for a new fridge. He was to show Mrs. Ebbett a range of choices at 11 am the next morning.

In mid-January, my father had gone to Auckland to look at a business for sale, in Karangahape Road. They wanted £1,000. My father put in a stupid £300 offer and it was accepted. The vendor also agreed to a £50 deposit and the balance to be paid from profits. The deal was to be finalised on February 4.

Tuesday February 3, 1931 was my first day at Mahora School. At 10.50 during morning break, came the devastating 7.9 Richter scale monster Hawke’s Bay earthquake. New to the school I hadn’t worked out which door in the hallway led to the playgrounds. I was thrown off my feet as several waves struck the school building.

Photo caption – James Wyllie – Kershaw Engineering

I Too Have No Regrets 11

In a blind panic I grabbed my cap, and found my way outside by the nearest exit. I remember seeing the swell in the school baths still sloshing water over the sides. I didn’t wait around for any instructions, I ran across the schoolyard and all the way home. A strange smell of smoky bricks hovered in the atmosphere everywhere. All the way home, little infants were gripping their mother’s legs or on the footpaths in tears.

When the world started to move, my father had been standing outside Thompson’s Butchery in Heretaunga Street West, just marking time until his appointment to demonstrate a new model fridge to Mrs. Ebbett. The Napier Gas Company showrooms were just around the corner on King Street. He immediately ran 15 yards passing the grocer’s shop to the corner of Heretaunga Street and King Street, then the force of the shockwaves threw him off his feet and headfirst across the intersection into a large telephone pole outside the Cosy Theatre. Bricks rained down one by one, but none directly hit him, but slowly they buried both his legs and crept up his torso. Luckily the Cosy Theatre had been poorly built and the bricks separated and didn’t fall in large lumps.

Exactly where he had been standing, 38 year old clerk Julia ’Ivy’ Thompson had rushed out of her father’s shop and had been crushed by falling masonry. Across the road seventeen people perished as the façade of Roach’s Department Store crashed into the centre of the road before the whole building caved inwards. Dad extradited himself from the bricks, grabbed his bike from outside the gas company and rushed home to comfort us.

My father found mum standing on the footpath outside home. Dad set off on his bike for the school to bring me home. But couldn’t find me anywhere. He was most relieved when he arrived home again to see his terrified youngster hugging mum outside our home. I remember Dad arriving home on his bicycle, his suit covered in dust and totally missing the seat of his pants. Both business districts of Napier and Hastings were heavily devastated by the quake and many buildings left in ruins. But additional devastation was to follow.

Like most of the private homes, both our chimneys had come smashing down. The main fireplace fell outwards and not through the roof into the living area. Disastrously the little chimney in the kitchen had come down through the roof. My mum was left with china, glassware, crockery, jam sauce, jars of preserves and wall hangings, smashed or broken on the floor of our home. My grandparents had suffered ill luck. The façade of their delicatessen had collapsed, along with the neighbouring Donovan’s billiard saloon and the large five storey Grand Hotel, spread a mountain of debris that blocked easy access to the area.

My father went back into town to look for his mother and sister, who both worked in the ‘Elite’ delicatessen shop. He clambered over the rubble in the street to find amazingly the shop intact. As it was a wooden building it had ridden the storm and only the ferro-concrete front had crumbled. My grandparents and aunt lived on the second storey and he climbed the stairs which had remained undamaged. He found no one and discovered not even one glass had been broken. Dad was relieved to hear that his mum and sister were at the home of Miss

Photo caption – The King Street and Heretaunga Street Intersection after the earthquake.

I Too Have No Regrets 12

McKennie, a family friend.

Elite Bacon Company, wooden storage building, cool storage building, bacon factory and petrol station at Stortford Lodge.

At Stortford Lodge, the brick building housing the petrol station was a total wreck, but the wooden bacon factory was practically undamaged. Luckily the fruit picking had not started, but there was still the problem of no power to run the refrigeration for the meat stocks. By 2 pm it didn’t matter as the emergency relief committee commandeered all the stock from both the delicatessen and the factory. The dodgy office clerk had bravely rescued the cash books from the safe. Not surprisingly he was never to hand them over, and burnt them to cover his murky tracks. The landlord had adequate earthquake insurance for the shop, but my grandfather had never taken out any insurance on his premises at Stortford Lodge or the contents of the Heretaunga Street shop.

In the afternoon, my father and a young employee Jack Kelly returned in the old Chevrolet truck to salvage the stock and some belongings for the shop. It was nerve wrecking as more shakes were occurring regularly. My grandfather’s 1924 Austin 12 Tourer was undamaged in the brick building behind the shop, but was trapped by a large timber beam. They planned to return the following day to collect more belongings. My grandparents and aunt, suddenly homeless, came to live with us. They had practically lost everything in the earthquake.

Amongst the 151 aftershocks that day came a severe shock of 5.8 at 8.41pm. Much more of the Grand Hotel came crashing down on to the surrounding properties, but it also ignited a broken gas line in Bell’s Grocery on the Russell Street corner. With no water available for fire-fighters, the furious fire went uncontrolled, eventually sweeping through my grandparent’s wooden dwelling and gutted every building in the block on Heretaunga Street and Karamu Road. My mother’s sister woke us at 5 am with the bad news. My grandparents not only lost the equipment from the stop, but their car and the remainder of their personal belongings, including Granny’s beautiful linen and handiwork. Auntie Winnie lost her cherished Fritz Kuhla piano. All were taken by the fire.

Until our chimneys was repaired, we were not permitted to live in our house. No one wanted to live inside our house any way, as the region experienced 612 aftershocks before the month was out. We owned a large tent, which was erected on the back lawn, but most of the extended family slept inside our large garage. The final death toll of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake rose to 256, with hundreds more injured in varying degrees.

Meanwhile, my father volunteered for the special police force and he was one of three appointed as an inspector for the next ten days. This quasi-military force was to keep law-in-order, control the CBD and help with

Photo captions –

‘Elite’ delicatessen still smouldering the following morning.

Fire destroyed the whole northside of Heretaunga Street.

I Too Have No Regrets 13

the evacuation. Dad didn’t get home for a sleep for three days. There were 306 men employed on picket duty at every intersection every minute of the day. One of my father’s earliest tasks was to drive a group of nurses to the emergency hospital in the huge camp in Nelson Park, Napier. It took hours to negotiate the huge cracks in the coastal road, only to find Napier more devastated than Hastings. He chose to return to Hastings via Taradale, which was a mistake as the roads were almost unpassable and the Waiohiki bridge down. One day while manning the pickets, his team even refused to allow the Commissioner of Police passage and the esteemed gentleman was forced to take a large detour, but took it in good humour.

My father received a certificate signed by the Mayor George Roach, in appreciation of his services as a special constable, which I still possess. During the week, my father was surprised to get a cable saying the Nelson bacon factory venture was opening on February 23 and the position was his if he still wanted it. I think my father felt a little guilty leaving Hastings in its hour of need, but mum’s wisdom shone through. He accepted the position in the South Island. My grandparents and Aunt Win would stay in our house, as they were still homeless. My parents loaded our faithful 1928 Detroit built, straight eight cylinder Hupmobile Tourer with crockery, utensils, bedding, Betty and myself and we were off. We sailed across on a Cook Strait ferry Arahura and I remember being seasick.

Therefore, my father became manager of the Blackbyre Bacon Company at Appleby and was promised 10% of the profits and a weekly wage of £6. Wyllie had organised accommodation in a small cottage in a back paddock, where I would have to wade across the river to get to school. My father dismissed the offer and found a large bungalow in Queen Street, Richmond for 22 shillings and six pence weekly rental. Dad brought some furniture from the mart. We later moved to a new bungalow, straight opposite, with a rental of just 17s. and 6d.

Wyllie had made several improvements, some good and others were bad. Hence the factory was still quite crude and some machinery was still being installed. Wyllie had organised five employees including Charlie Austin a 56 year old butcher from the West Coast, Frank Wagner and Harry Best an engineer to run the plant, refrigeration and steam boiler. But Dad was still the curer, boner, roller, smallgoods man, salesman and bookkeeper. They had an Albion five ton truck available, which did five miles to the gallon. Wyllie operated a 30 acre pig farm on the opposite side of the road, where he introduced the Large White breed of pig. Over nine months, 12 sows produced 156 piglets but only 24 survived the winter, most succumbing to pneumonia. Dad managed to get the factory running smoothly, although the depression made things demanding.

By March 4, my grandparents who had lost almost everything had established temporary premises in 423 Heretaunga Street West and the ‘Elite’ Pork shop operated from this location until the old premises were rebuilt the following year. This building was in front of Alex Manson’s machinery business. It was situated next to Bill Carberry’s saddlery. We had purchased Lassie from him. The wooden factory building at Stortford Lodge remained and was only eventually demolished to make way for the present Cumberland Court Motel in 1999.

My grandfather was about to gain an earthquake recovery loan from the treasury amounting to £1650 to rebuild the cool stores at Stortford Lodge. While he was rebuilding the cool stores, outside operators moved in and afterwards his income from the cool stores dropped by an average of £6,000 per year.

After the rebuild, my grandfather already had accommodation, so opened the ‘Elite’ delicatessen a few doors from the previous location, below Donovan’s billiard saloon at 120 Heretaunga Street East. After a few years, he relocated again to 118 Heretaunga Street East, beside the State Theatre.

After five weeks in Nelson, no one had received their wages. Dad arranged with the bank for a weekly cheque to pay the employees, so no one would be caught out if the venture failed. Flyblow was a major problem, because of the manure pit. The Nelson Freezing Works at Stoke had offered to kill the pigs for 2/- 6d and store them until needed but Wyllie blindly couldn’t see the financial benefits.

Wyllie had accepted orders not realising it took six weeks to product the products. They secured Tamworth pigs from Takaka which were outstanding meat producers, and some Berkshire pigs. Dad secured the ham and bacon supply to J.Wood and Son, who were the leading grocery in Nelson.

Photo captions –

H.B. Herald Tribune

4 March 1931

Heretaunga Street showing the ‘Elite’ delicatessen block after the rebuild.

I Too Have No Regrets 14

Unfortunately Dad had problems with Harry Best enjoying too much of the factory‘s previous product, so Jock Brough became the new factory engineer. The factory was killing 40-50 pigs every Monday. Dad had a small but efficient operation. In the first year, they made a profit and the following year the books were looking even better, and my father received a £1 weekly wage increase.

Regrettably, the Governor General Viscount Bledisloe made an official visit to the Blackbyre Bacon factory. He was a breeder of pigs and had his own bacon factory. He suggested to James Wyllie that killing 120 pigs a week was the only way to make ends meet. Wyllie started making big plans. He bought in pigs to fatten on pea hay and applied for an export licence. This proposal meant the local health inspector Dr. Mercer called to inspect the premises. Dad was given 24 hours to get rid of the digester, which he hated, and was happy to oblige.

The factory owner purchased a new refrigerator from England with a Tangye diesel motor. Sadly, the diesel motor couldn’t develop the required power to sustain the cooling unit. My father had been very successful, phoning the local outlets every morning to obtain orders. Wyllie decided to send Jock the engineer door knocking every morning and sales quickly fell away. My father quickly reverted back to his successful selling practice but Wyllie cut everyone’s wages by 10 shillings a week to cover the losses. He soon tried again to reduce the wages, but this time my father stood firm.

I had to go into wearing glasses when I was eight years old. I was getting continuous headaches and a Nelson optician put me into spectacles. At primary school and at home I would always be drawing motor vechiles [vehicles]. Just about every time it would be a stylish sports car, open top with long flowing guards.

During 1934, the Rangitikei Bacon Company in Marton, went bankrupt and my father had read an advert for the leasing of the factory in the Dominion newspaper. James Wyllie and my father were still having their differences and argued a lot. Dad had found the cheapest and most successful form of advertising Blackbyre products, was window displays at several outlets. In September 1934, he had just completed a new display in Howcroft’s Grocery Store, when Mr. and Mrs. Wyllie removed it and created their own presentation. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Dad threw the keys across the table and within a week our family had embarked on the Arahura and moved back to Hastings. Within 18 months, Wyllie’s venture would be bankrupt, and he lost the farm, the factory and almost everything.

My father went to Marton to check on the prospects of the Rangitikei Bacon Company. This was just a one-man business in Hair Street, behind Panny Lurajud’s fish shop. This Greek gentleman owned the factory and supplied the refrigeration. The lease was £3 a week. Lurajud had a medium sized Reo truck and was prepared to do all the bacon factory’s carting. Dad recommenced operating the Rangitikei Bacon Company. I stayed in Hastings with Auntie Gert for a short period until my parents had found a house in Marton.

While in Marton, we lived at No. 1 Station Road, near the Tutaenui Stream which ran past our property and was always in my mind as a flood risk. The house was owned by Mr. Leonard Carey, a local builder, and the rent was 25 shillings a week. This time my parents had most of their furniture moved from Hastings to Marton. My father worked tirelessly on his own and build up the small business. At first, the suppliers were weary having suffered a financial lose with the previous owner but Dad started curing for the local farmers.

My father had always banked with the BNZ and before leaving Nelson got a credit reference from the branch manager. He gained a £180 overdraft by depositing his insurance policy as security. Eventually he needed another £25 and the bank manager was reluctant to give him more credit. Consequently, he switched to the Union Bank of Australasia. Here he was aided by the generous support of his bank manager Mr. John Thorp, who increased the overdraft to £400.

Regrettably the floor of the curing room collapsed, but the owner converted another room into a refrigerated curing facility. He also installed a new 30 gallon gas copper which cost £12. A gas line had to be laid passing Panny Lurajud’s home. Then came another obstacle, the steam boiler was condemned.

Dad had been fascinated by Holly self-raising flour brand, made by Buchanans Flour Mills in Ashburton, and their advertisement appeared in the old Edmonds Cookery books. My father chose ‘Holly’ as the possible brand name for his products and began using it, as there were no copyright issues. The factory made a small profit for the first year and my mother took over the clerical side of the business. Dad would drive to Bulls, Palmerston North, Halcombe and Feilding to secure new customers and get weekly orders.

One day I was riding my mother’s bicycle and at a good clip as usual. I misjudged a corner and hit the roadside gutter. Bike and I went flying, and I received several bruises. Alas Mum’s bicycle did not fare too well. It had a U shape bend in the front wheel. I had to pay off three-pence a week to my father until the repair bill had been recuperated.

By 1937 my grandfather’s business had still not recovered from the 1931 disaster and he could not repay the loan from the treasury or any of the mortgage taken out with William Richmond. He applied for relief of mortgages through the new ‘Mortgagers and Lessees Rehabilitation Act of 1936’. He gained a satisfactory arrangement, but the consequence was he was ineligible to get any more accommodation from the bank. Dad received a letter from the manager of the National Bank in Hastings, stating that the ‘Elite’ Bacon and Ham Company was in a dire financial predicament. He suggested if my father could come back to Hastings and take charge of the ailing business and invest £1200 into the business, they would extend the credit limits. Otherwise the business wouldn’t last six months. Dad spoke to his father, but he seemed impervious to the serious state of his finances.

I Too Have No Regrets 15

Dad had always considered returning to Hastings to commence his own enterprise and now seemed the right time. My father wanted to create a completely new business and he found advertised in the newspaper a suitable arrangement. Harry Mossman, a land speculator offered to build new premises on a large spare section on Karamu Road, between the newly built Thompson Motors and the Public Trust Office, which was situated on the Queen Street corner. He was happy for architect Robert McDowell to create a structure to house a new factory to my father’s specifications and to fulfil my father’s requirements for a bacon processing facility.

Afterwards the basic agreement to lease the premises from Harry Mossman for a designated period was signed. The rent would be £3 and 10 shillings per week for five years, with the right of renewal for another five years. Charlie Palmer was awarded the contract to build the premises, after submitting a reasonable tender. Immediately he hit a snag, when he was presented with the architect’s plans which included the technical tongue and groove method and using no nails. This was quickly rectified when the agreed set of plans were produced which stipulated nailing of the skeleton framework.

With his plans in place, Dad did not renew the Marton lease for a fourth year. We returned to Hastings on Labour Day in 1937 and we went back into our old home in St. Aubyn Street West. My grandparents and Auntie Winifred had to move out and found a nice residence at 106 Park Road South. While the factory was being constructed, my father drove again for Wilkies Transport for a short stint. He vowed he had never worked so hard in his life than during this period, when he was employed by Wilkies.

Dad hoped to be operating by Christmas and received a small stock of frozen legs of pork but the opening target couldn’t be achieved. For that reason, he gave all the pork to his sister to sell at the delicatessen, as Nelson’s Tomoana Freezing Works were already refusing to supply my grandfather. In 1937, Kiwi farmers produced more than one million pigs for the New Zealand market.

The ‘chippies’ under the local contractor Charlie Palmer had put the final excellent touches to the factory in early February and the new Hastings Bacon Company officially opened for business on February 19, 1938. An indication of Dad’s confidence was the expenditure to make the premises thoroughly up-to-date. He made provisions for future expansion. Utility was not sacrificed for beauty, as it was most convenient and very few steps were necessary to get around all the essential parts of the factory.

The refrigeration unit for the factory was the first contract awarded to the newly created Agnew Refrigeration Company. Ted Tucker installed a unit, built by Hallmark in England. It was fully automatic with two Larkin Coolers installed in the curing chamber. These coolers were fitted with electric fans which run for 24 hours a day, thus ensuring complete uniformity of temperature throughout.

The cooking of the ham was done by gas, operated under controlled heat which ensured the retention of the valuable meat juices in the hams during the process. The whole building was thoroughly ventilated by a current of air and the glass doors and skylights made it a healthy and well-lite factory.

Originally the quality pigs were selected from local farms and slaughtered under excellent conditions and Government inspection at Tomoana Freezing Works. Now the ‘Holly’ brand had a new home and this very high-grade product would be available in more local outlets.

My mother continued with all the book-keeping and ledger entries for the company. The Hastings Bacon Company took a postal box, P.O. Box 71, Hastings. This is still our postal address, 80 years later.

Photo captions –

H.B. Herald Tribune- May 7, 1937.

An aerial photo from 1934, showing the vacant sections north-east of the Public Trust building.

Hastings Bacon Company

I Too Have No Regrets 16

By commencing business in Hastings, my father went into direct competition with his father. Meanwhile my grandfather’s businesses was completely floundering and rapidly he found bankruptcy papers being served on him. Two bad seasons in 1937 and 1938 finally saw the curtain come down. My paternal grandfather had been battling the bottle for years, which didn’t help. The bookie at the Stortford Lodge Hotel was also gaining a regular profit.

My father’s business flourished under his astute management. He began by processing just ten pigs a week, until he had established a reliable cliental. Within a year, he was killing ten every day. We sourced the pigs direct from the farmers as far away as Woodville. They arrived by rail, already killed and dressed.

Being an energetic twelve year old, already with a mechanical bent, life was exciting. Sure, I was supposed to help my father, before school, after school and occasionally at lunch time. Even in the school holidays, I was unofficially helping the family business. I was given no pay but Dad would put a little directly into my POSB account. Sadly, our return to Hastings, brought the decision to put my best mate Betty down. Dad had imported her from England as a puppy in 1928, and on the long sea journey, she had been poorly nourished and suffered irreparable damage curtailing for longevity.

Wilkies transport did all our carting of pigs from the abattoir at Tomoana, and transporting orders to and from the rail head. Alex Wilkie’s son Cyril took over the business later. How did we ever get away with carrying carcases on an open truck tray with just a tarpaulin over the pigs.

In November 1938, the ‘Elite’ Bacon Company went into liquidation, my grandfather appeared before the High Court in Napier and was declared insolvent. The delicatessen location at 118 Heretaunga Street East continued until a next court hearing. Afterwards 118 Heretaunga Street East became a marble bar for Health Foods (NZ) and eventually during the war, changed its name to the Tip Top Milk Bar.

On 17 February 1939, my grandfather appeared in the Hastings Courthouse to face the bankruptcy proceedings. He had been declared bankrupt on the 9 February. He was represented by his solicitor Mr. Hallett. The main creditors were Atlantic Union Oil, the Treasury, National Bank, William Richmond and three employees. These secured claims amounted to £8272, while there was £1762 owing to unsecured creditors.

His main assets included a life insurance worth £9000, but with a surrender value of only £412. The shop and bacon factory had been for sale for two months, without receiving any offers. Carl Vogtherr stated the land building and plant cost £7540 and there had been £5000 spend on additions and improvements. His other assets included two petrol pumps and three tanks, an air tank and motor pump worth £45, stock including 30 gallons of benzine, two gallons of oil and 400 blocks of ice. The only machinery was a typewriter, Chevrolet truck Reg.No.H9020 and a large tarpaulin.

The three employees Jack Kelly, Bill Wilkins and Mr. Duckitt were claiming a substantial amount for wages not paid. Wilkins was claiming for 8 weeks and 2½ days at £5. 8s. 2d. a week. Carl Vogtherr could not confirm the amounts because the wages book had not been kept up to date after the office accounts clerk David Graham took ill. David Graham had begun suffering from blood clots in his legs. Thrombosis claimed his life, as the clots travelled to his brain. David would die aged 34 years old, on April 16, 1939.

The Official Assignee estimated the total assets were £1230. 5s. He made a tentative judgement that there was a £248.16s. 9d. deficiency, but everyone knew the true figure was much higher.

Soon afterwards part of the Stortford Lodge site was sold to Mr. A Robson, while the mortgagee William Richmond took the remainder. The tentative price for the land was £4,000. The fruit cool stores at Stortford Lodge became the Richmond Cool Stores. Richmond sold the bacon factory to L.J. Fisher and E.E. Rixon. It became the Stortford Lodge Bacon Company operated by Mr. Rixon, with Fred Green as the curer. The bowser station was abandoned, with no parties interested in operating it. The Chevrolet truck was sold to Mr. E. Wiggins, 606 Oak Road.

My grandfather began earning a living by growing vegetables at home and selling them from his gate. He never drunk alcohol or gambled again. Aunt Winnie went to work for L.J.Harvey Ltd, eventually giving 24 years loyal service. My father made a pledge to pay out all the creditors who wanted reimbursement, to ensure that the Vogtherr family still had a good name. This took many years to achieve. By July 1948, my father had paid all the

I Too Have No Regrets 17

preferential secured claims. By January 1950 he had paid off £545 of the unsecured claims but still had over £433 unsecured claims outstanding. Finally on 13 November 1952, my father paid off the last claim. One cheque had been generously returned, and my father paid off another two unrecorded claims, including £20 to C.H.Slater.

In the early days of the Second World War, Dad was conscientious and did his best to save petrol and was allocated the minimum number of coupons, two gallons of petrol per month. That wasn’t too much of a problem because we only lived about ¾ of a mile from the factory. Before the war, I would do local deliveries to customers on a factory bike, with a large carrier basket. During the war and while I was at boarding school, the Hastings customers were still supplied by this delivery bike. Freight costs from the abattoir and railhead was ½ d. per lb. The pigs cost my father about £3.10s.

When Dad found out that George Passey and George Green, the panel-beaters next door had been allocated 40 gallons of petrol a month, he found it difficult to accept. During those days when severe rationing was in force, many would beg, borrow, bargain or buy any coupons that might be circulating. Dad’s friend Mr. Thomas Clissold, became affectionately known as ’Father Christmas’, because of his uncanny ability to produce these valuable petrol coupons more often than not. He was a small robust man, with a ruddy complexion and always had a cheeky grin. He always wore a brown suit and hat. He had told us that in 1912, he was a cook on the ‘Terra Nova’ during Captain Falcon Scott’s ill-fated Antarctic expedition. We thought it was a tall tale and didn’t believe him, until one day to our astonishment, he turned up with King Neptune’s three foot long wooden razor, inscribed with the words ’Terra Nova’ on it. Mr. Clissold must have filched it, as a souvenir during the voyage. One wonders where the wooden razor is today?

To my knowledge the family suffered no anti-German sentiment during the Second World War. Although the Department of Justice and Department of Internal Affairs both opened a file under my grandfather’s name in 1940. During the war my father purchased a furnished beach cottage at Te Awanga for £460. It lay on the northern end of the lagoon, with a lovely view of the Bluff Hill at Napier.

My Sporting Memories

After helping my Dad in the bacon factory after school, I would run alongside his bicycle, all the way home about a mile away through the streets of Marton. One evening the local tailor Mr. Twigg saw me and asked how far I thought I could run. “Down to the railway station and back.” I replied. He was surprised, as this was about a mile. He was an official of the Marton Harrier Club and suggested to my father that I should join the local club. At the time, the club had a strong reputation in the region, and Frank Hill was the best runner in the club. He had many royal battles with Charlie Wellar of Wanganui, the three time New Zealand Harrier Champion. My father went and talked to Mr. McPherson, the local Gas Company manager, and D’Arcy Foster the foreman at the Ford dealership in Marton. They were both active members of the harrier club. My father allowed me to start running and therefore I commenced racing when I was still only ten years old.

In 1935, I joined the club. I came under the guidance of a couple of the local runners. The club’s president, Mr. Dashwood organised a series of three races for 9 to 11 year olds at Marton Park. On a 440 yard track, the races were over one lap, two laps and three laps on successive weeks. I finished with two seconds and a third placing, and just a point behind the overall winner. I received a miniature cup for being runner up overall. My first trophy, and still treasured today.

I joined the Hastings Harrier Club for the 1938 season, along with other juniors including Peter Single, John Campin and John Philpott. We all came under the guidance of club stalwarts Colbourne Wright, Tod Taylor and the Spurdle brothers, who gave us helpful advice with training and racing. Unfortunately, the Hastings club did not have a separate junior grade. We could keep up with many seniors over short distances, and from the beginning were trying to outrun as many seniors as possible. I have vivid memories of laying a paper trail with Jim Moran after the big flood of 1938. We both waded through mud up to my hips down Poplar Avenue on April 30, five days after the heavy rains.

Later in 1939, I remember running down Karamu Road, passing the Showgrounds with Bill Tully, during the annual Napier to Hastings Road Race. Because of my age I couldn’t compete, so I ran part of the course as a training run. By now, my father was getting worried that I was punishing my body and would burn out. Les Spurdle, the harrier club’s coach and handicapper supported my father’s suggestion to moderate my athletic ambitions, by sending me away to New Plymouth Boys’ High School

I rejoined the Hastings Harrier Club in late 1942, but because of the war there was very few organised racing. Many other clubs were in recess and there were no official championship races. The club had introduced a junior grade and my first race back was the inaugural six mile Clive to Hastings Road Race for junior runners in September. With only my reputation to go by, the handicapper ungraciously started me off scratch, ten minutes behind the limit runners. I did record the fastest time 36.30 but I never caught two runners off more generous handicaps. C. Baumfield off a 10 minute handicap was still 74 seconds ahead of me at the finish, and W. Shattky

Photo caption – Two early harrier images of me.

I Too Have No Regrets 18

off 8 minutes was still 59 seconds clear at the finish.

I won the Hastings Junior Club Championship over 5,000 metres the following August, in 20 minutes dead. In the 1943 Clive to Hastings Road Race I was again off scratch, but this time I won both line honours and recorded the fastest time. Henderson off 5 minutes was second, John Philpott (6.30) was third, while the previous year’s winner C. Baumfield (4.50) was the next finisher. The weather that day was atrocious, and everyone was frozen stiff by the time they finished at the Hastings Post Office, in Russell Street. Luckily soaking in hot water was available at our factory in Karamu Road, but still many were overcome by severe muscle cramps. That was the coldest I ever experienced while harrier running. Mum started a scrapbook, to record my running achievements and the achievements of my other athletic heroes including Doug Harris.

1944 was my final season as a junior. I specially targeted the six mile Clive to Hastings Road Race again. I was training conscientiously and running confidently, with an eye on the first ever National Junior Cross Country Championships to be held at Miramar, Wellington. In the local event, I was off scratch again, paired with Albert Pay, a visitor from the capital. The conditions were the complete opposite to the previous year. A very hot Hawke’s Bay day. Albert and I were well matched and ran stride for stride until we reached the three mile peg at the Karamu Stream bridge. We had both worked hard and were feeling the strain, but I decided to put in a surge, just to test the water. Surprisingly there was no strong response and he dropped behind. He still made me work for my sixth placing but I crossed the finish line at the Post Office in a new record of 33 minutes 10 seconds. The 1944 season was a good one as I won both the senior and junior club titles, which probably still hasn’t been repeated by another runner.

July 22, 1944 Hastings Harrier Club Championship

Senior Grade-6¼ miles: 1. Gordon Vogtherr

Junior Grade-3 miles and 220 yards: 1. Gordon Vogtherr

August 5, 1944 Hawke’s Bay-Poverty Bay Provincial Harrier Championships at Hastings.

Junior Grade-3 miles and 220 yards. 1. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 19.33½, 2. Guy Instone (Has) 20.16, 3. David Lowe (Has) 21.43.

On September 23, Mum and I travelled to Wellington for the national harrier champs. The race was over 3 miles and 220 yards, on a good testing course with hills, road and a cross country section at Miramar. Pete Tulloch and Albert Pay were able to burn me off although I was only 20 yards behind at halfway. In a desperate finish, I was credited with equal third with Neil Stanyer from Auckland. The Auckland runner had come with a powerful late challenge and I was not aware he was challenging until the last two strides. Thankfully there was no photo finish cameras in those days, otherwise one of us could have been disappointed. My time was 19.58, some 38 seconds behind the winner Tulloch. Unfortunately, this ultimately ended up being by far my best harrier placing on the national stage.

After the cease fire in 1945, life gradually returned to normal as servicemen returned to civvy street. My father, Reg Cabot, Colbourne Wright and others reformed the Hastings Athletic Club. I was keen to run track, to bridge the summer gap between harrier seasons.

1945 was my first year in the senior ranks and with many servicemen returning to civilian life, the competition was expanding. I took out the fastest time for the King’s Birthday Road Race in Napier and again I was successful winning the senior club title. It was raced in prefect conditions overhead, but the ground was very heavy and greasy after recent rain. As well I won the first Hawke’s Bay-Poverty Bay Senior Harrier Championship to be held since 1941. I won comfortably from Tod Taylor, who had won the title three times prior to the war. The time was a slow 41 minutes 15 seconds, illustrating just how challenging the Taradale course could be.

I travelled to Dunedin for the N.Z. Cross Country Championships and while flying south, they announced that peace had been declared, V. J. Day. The races were held in wet conditions on the Wingatui racecourse. I finished a creditable sixteenth. A week later I ran the Heretaunga Baton race for the first time. This was an annual four man baton relay race, from Hastings to Napier between the two local clubs. I was lead off runner and our team won by almost three minutes. On September 15, Dad drove three of us to Wellington for the Vosseler Shield at Lyall Bay. In a field of 111 competitors, Tod Taylor came seventh, Tom Manley fourteenth and I was a further two places back. This was my first ever 10 mile event and I lacked the conditioning for the extra distance.

July 21 1945 Hastings Harrier Club Championship at Havelock North.

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Gordon Vogtherr 41.00, 2. H.E.Taylor 41.34, 3. Bernie Anderson 43.36

August 4 1945 Hawke’s Bay-Poverty Bay Provincial Harrier Championship at Taradale

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 41.15, 2. H.E.Taylor (Has) 41.51, 3. G. Healey (Gis) 42.55.

When we lived in Havelock North, I would regularly train over the club championship course, which ran past our front door in Duart Road. Also, I often ran home from the Hastings boundary after work. One day, my father dropped me off at the boundary. It was only as his car disappeared towards Havelock North, I realized I had not

Photo caption – The titanic lunge to finish third equal at Miramar.

I Too Have No Regrets 19

put my shorts on. That particular run home was very fast.

During this period, many club runners just ran in sandshoes. I was lucky I had a pair of proper soft leather running shoes, which were good for road running. But I needed more grip for the grass tracks and especially the winter cross country racing. Spikes were only just starting to appear overseas, but only the top international athletes had them. Anyway, I found my running style did not suit spikes. I cut some rubber soles into horse shoe shapes and glued three to each running shoe as cleats, similar to those used by baseball players. They were surprisingly affective and gave tremendous grip. I could run on all surface with the cleats and suffer no discomfort or loss of performance.

In March 1946, Bill Wells, the West Coast-North Island Harrier champion, attempted to break the New Zealand six mile record in Hastings at Nelson Park. Hastings athletes, including myself, were invited to act as pacemakers. He broke the record with a time of 30 minutes 55 seconds.

I recorded the fastest time at the King’s Birthday race in Napier. For the first time since 1941, the hugely popular Anderson Rally at Dannevirke was conducted. I ran a solid race for fifth place in a field of 52 starters. Later in the year I lost my club title. The course was very heavy with ankle deep mud and the creeks in flood. But I retained my provincial harrier title on the same course at Havelock North by over two minutes.

Unfortunately, at the New Zealand Championships three weeks later things didn’t go to well. I had surveyed the Trentham course on Friday afternoon and it was hard and fast. With atrocious overnight weather and more heavy rain and a bitter southerly throughout the next day, the ground was a slippery, waterlogged challenge. This played into Jim Matheson’s strengths to finish 21st. while I struggled to stay upright in the mud and finished 31st. Cliff Cox passed me ploughing through the appalling footing. He was minus his shorts, which he had lost to the mud. That day the annual North verse South rugby match at Athletic Park was called off after 65 minutes.

June 8 1946 Anderson Rally at Dannevirke.

Senior A Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Ken Galloway (Pal.Nth) 34.40, 2. L.Hawthorn (Pal.Nth) 35.05, 3. V.Fiddes (Pal.Nth) 35.15, 4. Clem Hawkes (VicU) 35.47, 5. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 36.00.

July 6, 1946 Hastings Harrier Club Championship at Havelock North.

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Jim Matheson 40.34, 2. Gordon Vogtherr 41.26, 3. George Foulds 43.18

July 27 1946 Hawke’s Bay-Poverty Bay Provincial Harrier Championship at Havelock North.

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 38.31, 2.J.Matheson (Has) 40.40, 3.G.Foulds (Has) 40.52.

In 1947, Derek Turnbull joined the Hastings Harrier Club and we became very good friends and regular training partners. Derek was working for Mr. Tod on his farm at Otane and owned a brand new Triumph Speed Twin motorcycle. He was an enthusiastic runner and along with Jack Bartlett, Colbourne Wright, Jim Matheson and George Foulds, the Hastings club had a formable look. At the annual King’s Birthday open handicap road race, I arrived 10 minutes after my start time, but the officials allowed me to run unofficially, and with no warm-up I recorded third fastest time.

Three weeks later, I was third at the prestigious Dannevirke Rally. This was a very controversial race because a marshal sent us off course. There were numerous protests over the results. Then our club had to swallow a bitter pill, when we were defeated in the Heretaunga Baton race for the first time since its inception in 1934. I finished fifteenth in a field of 47 at the National Harrier Championships at the Ellerslie racecourse. I wasn’t too disappointed as I only faded over the last mile after lying eighth for most of the journey. This came on top of a disappointing third at Gisborne two weeks earlier, while defending my provincial title. Although our club did retain the Eagle Shield.

I won the club title the following month. At the end of the season, our club finished second in the Marton-Wanganui Road relay race behind New Plymouth. I ran the final leg into Wanganui, against Bill Wells the reigning NZ Harrier champion and George Bromley (Marton). I began the leg a minute behind Wells and 45 seconds in front of Bromley.

June 21, 1947. Anderson Rally at Dannevirke

Senior A Grade 6¼ miles: 1. John Eccles (VicU) 35.29, 2. Clem Hawkes (VicU) 35.30, 3. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 36.20

July 19, 1947. Hawke’s Bay-Poverty Bay Provincial Harrier Championship at Kaiti, Gisborne.

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Eric Tee (Gis) 41.34, 2. Jack Barlett [Bartlett] (Has) 42.29, 3. Gordon Vogtherr (Has) 43.05.

August 23, 1947. Hastings Harrier Club Championship at Havelock North.

Senior Grade 6¼ miles: 1. Gordon Vogtherr 39.25, 2. Jack Bartlett 40.42, 3. Jim Matheson 42.01.

September 20, 1947 Marton to Wanganui Road Relay

A Grade: 1. New Plymouth 2.15.16, 2. Hastings 2.18.57, 3. Marton 2.19.41, 4. Pal. North YMCA 2.20.03

I had won a solitary one mile provincial championships on the track, and three times secured the three mile title, but when Derek Turnbull arrived, I never saw which way he went and he took track titles with ease. I thought I was a reasonable track runner but quickly discovered I was a draught horse because I did not have a good

I Too Have No Regrets 20

finishing sprint. The six mile championship was held for the first time on February 21, 1948 and Derek recorded 33 minutes 22 seconds. I was third some 300 yards distant. I did run a track race in Auckland and was blown away by the opposition, reinforcing my doubts that I could ever be a good track runner.