DESIGN

FLAME into FAME

Honouring the work of two living treasures. BY DOUGLAS LLOYD JENKINS

The residents of Hastings seem particularly fortunate. Not in the frequency of blossom festivals or the abundance of Spanish mission architecture but in an art gallery (they call it an exhibition centre) that seems to serve them particularly well.

At the moment, Hastings is being exposed to a fairly typical combination of shows in the two-gallery building: a major touring show, Ans Westra’s retrospective Handboek, and Kamaka: The Ceramics of Bruce & Estelle Martin – a locally generated exhibition that celebrates two of the region’s (and New Zealand’s) leading arts practitioners.

Any art gallery or museum has two audiences to please: the visitors who come through the door, most of whom will be locals, and the wider audience of artworld professionals around the country. A successful gallery or museum balances both. Satisfying the first delivers attendance figures, while impressing the second delivers the all-important national reputation.

Not all art galleries get the balance right. Some ignore local patronage in search of national or international reputation. Others focus so strongly on the local community that they fail to appear on the national radar, which is good neither for those who work in them nor the communities they purport to support.

The Hastings Exhibition Centre gets the balance just right – an achievement reflected in its attendance figures. Seventy percent of its visitors are drawn from the local community and the rest are a mixture of tourists and art professionals who feel the need to make the trip.

Well-designed exhibitions, supported by modest but well-written catalogues, ensure not only that exhibitions at the Hastings Exhibition Centre are usually worth the trip but also that a permanent record remains of the scholarship brought together for such occasions. Because this is a relatively small organisation, it has become particularly good at looking around to find the right curator for the job, and often succeeds by convincing a candidate prepared to work outside their natural territory.

Kamaka was curated by Peter Shaw – well-known as an architectural writer and music and art critic but not an obvious choice as a curator of pottery exhibitions. Yet Shaw is something of an expert on the aesthetic connections between Japan and New Zealand, and the catalogue for this show contains some of his best writing – nicely nuanced, carefully contextualised and with a reference to the Czech composer Leos Janacek thrown in for good measure.

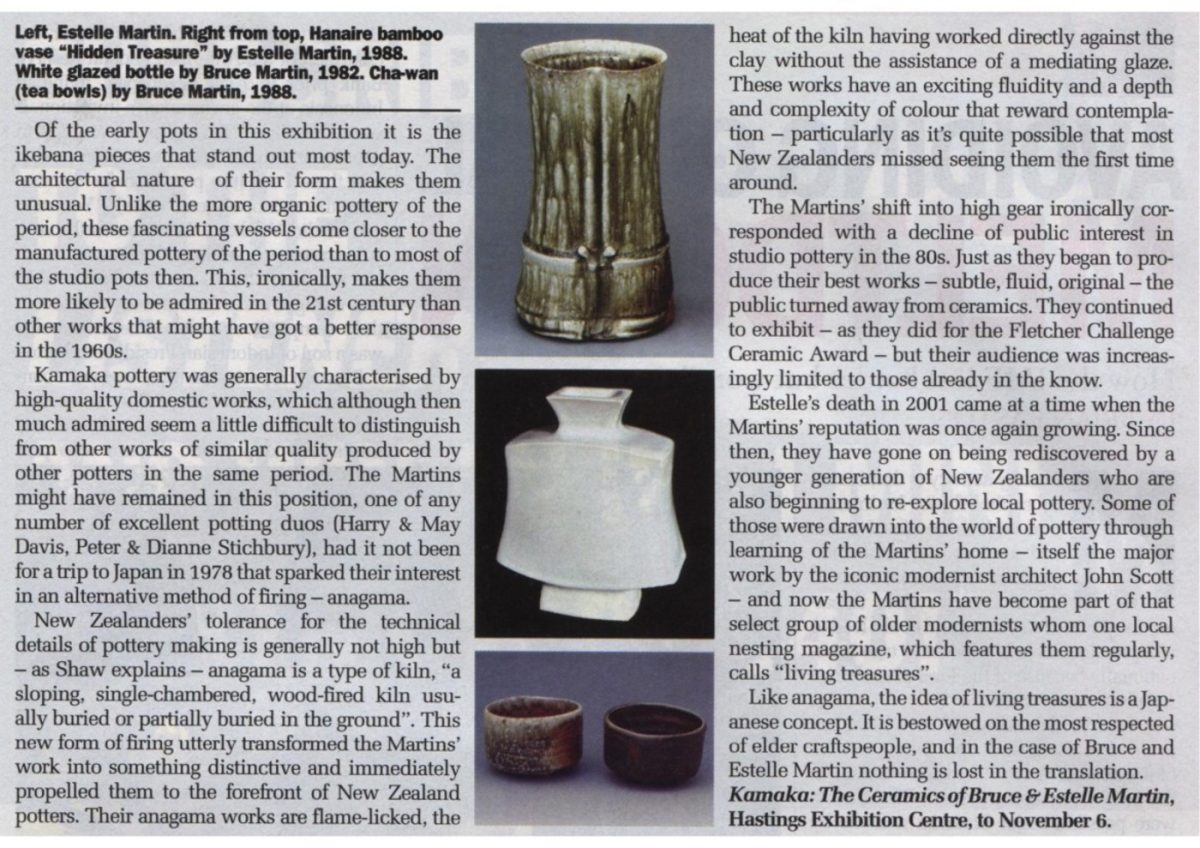

Where Kamaka does best, however, is in its careful handling of the first retrospective exhibition of two potters who found their personal métier relatively late in life. Bruce and Estelle Martin, of New Zealand and Scottish birth respectively, married in Hastings in 1950, and not long afterwards Estelle was introduced to Japanese aesthetics. As with many women of her generation, this happened through ikebana – the Japanese art of flower arranging – the austerity of which was just then beginning to find a place in the New Zealand imagination. In a way, the Martins’ story is a familiar one: unable to buy suitable ikebana pots, they decided to make their own. They became skilled potters (fulltime from 1965 on) and rode the wave of demand for studio pottery that lasted till the end of the 1970s.

50 LISTENER – THE THINGS THAT MATTER OCTOBER 22 2005

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.