don’t like artificial things,” says Estelle.

The house itself has a pottery feeling no wallpaper, but unpainted concrete block; no carpeting, but smooth red patio tiles in every room. Colourful tiles over bathtub and hand basins.

Even the name of the place – ‘‘Kamaka” – means rock of stone. “There is no equivalent word in Maori for pottery because it didn’t exist,” explains Bruce.

Light floods in high narrow windows, filters through bright draperies, heightening the woody hues of polished rimu, kauri, totara and matai. The feeling of natural texture continues in Douglas fir ceiling beams, stained black.

Comfortable upholstered furniture and woven throw rugs add the soft touch.

The Martins say they had no fixed ideas about what they wanted in their new house except to ‘‘have as little maintenance and housework as possible,” hence no venetian blinds, no wallpaper, no carpeting.

Left to architect

They left it entirely to the architect, John Scott, of Haumoana. “We felt that an architect is like ourselves, trying to create something,” says Bruce. “We don’t like being restricted by people saying ‘We want this size, this colour, this everything.’ Surely an architect must feel the same.”

Estelle adds, “John builds for individuals and got to know us before he began on the plans. He’d drop in at our other house to see how we lived, what we liked to do.”

The house is small, the rooms cozy, intimate. Yet, as Estelle says, “There is a feeling of space. John builds on a human scale.”

The residence is in two facing parts, connected by a covered walkway the left section for the Martins’ three sons (now grown up and living away), the right section for the adults.

The idea of two separate buildings was born when the eldest son drove his parents crazy with high decibel amplification, so they had to banish him to a room over the garage.

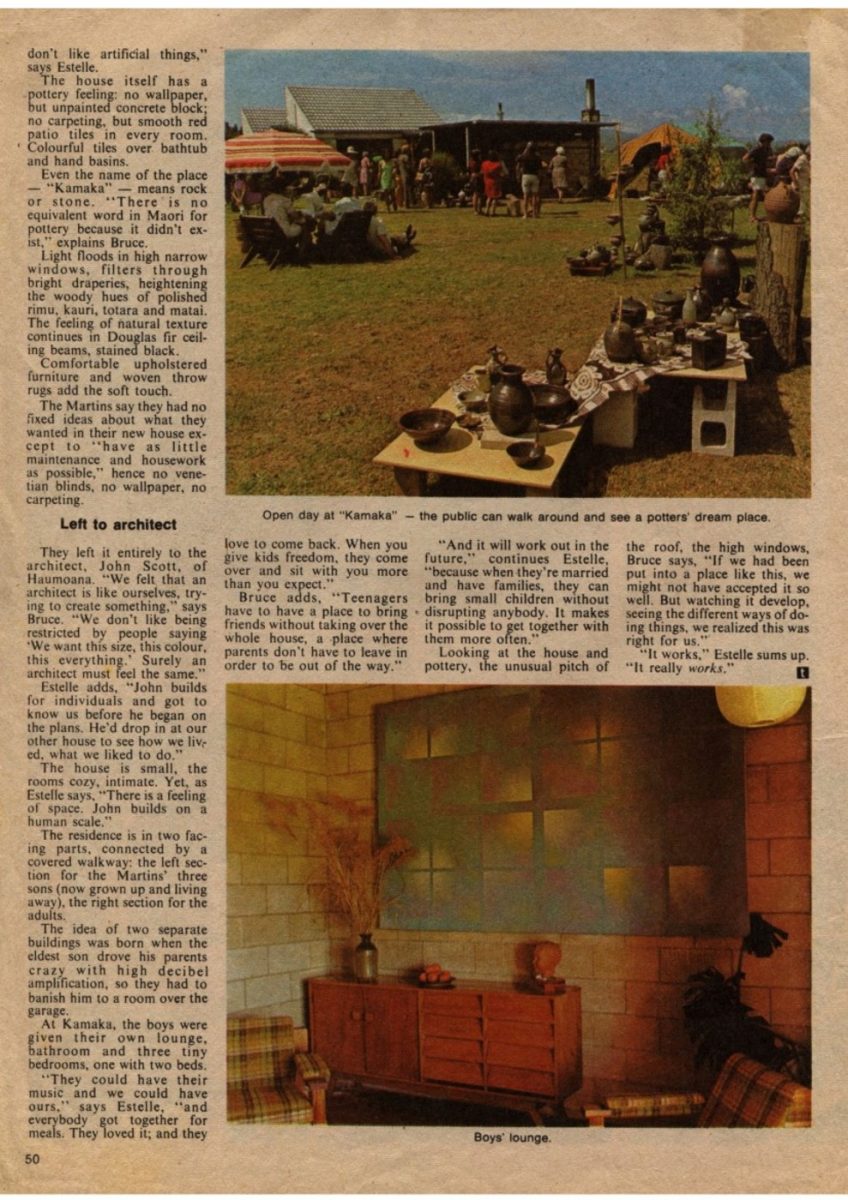

At Kamaka, the boys were given their own lounge, bathroom and three tiny bedrooms, one with two beds.

“They could have their music and we could have ours,” says Estelle, “and everybody got together for meals. They loved it; and they love to come back. When you give kids freedom, they come over and sit with you more than you expect.”

Bruce adds, Teenagers have to have a place to bring friends without taking over the whole house, a place where parents don’t have to leave in order to be out of the way.”

“And it will work out in the future,” continues Estelle, “because when they’re married and have families, they can bring small children without disrupting anybody. It makes it possible to get together with them more often.”

Looking at the house and pottery, the unusual pitch of the roof, the high windows, Bruce says, “If we had been put into a place like this, we might not have accepted it so well. But watching it develop, seeing the different ways of doing things, we realized this was right for us.”

“It works,” Estelle sums up. “It really works.”

Photo captions –

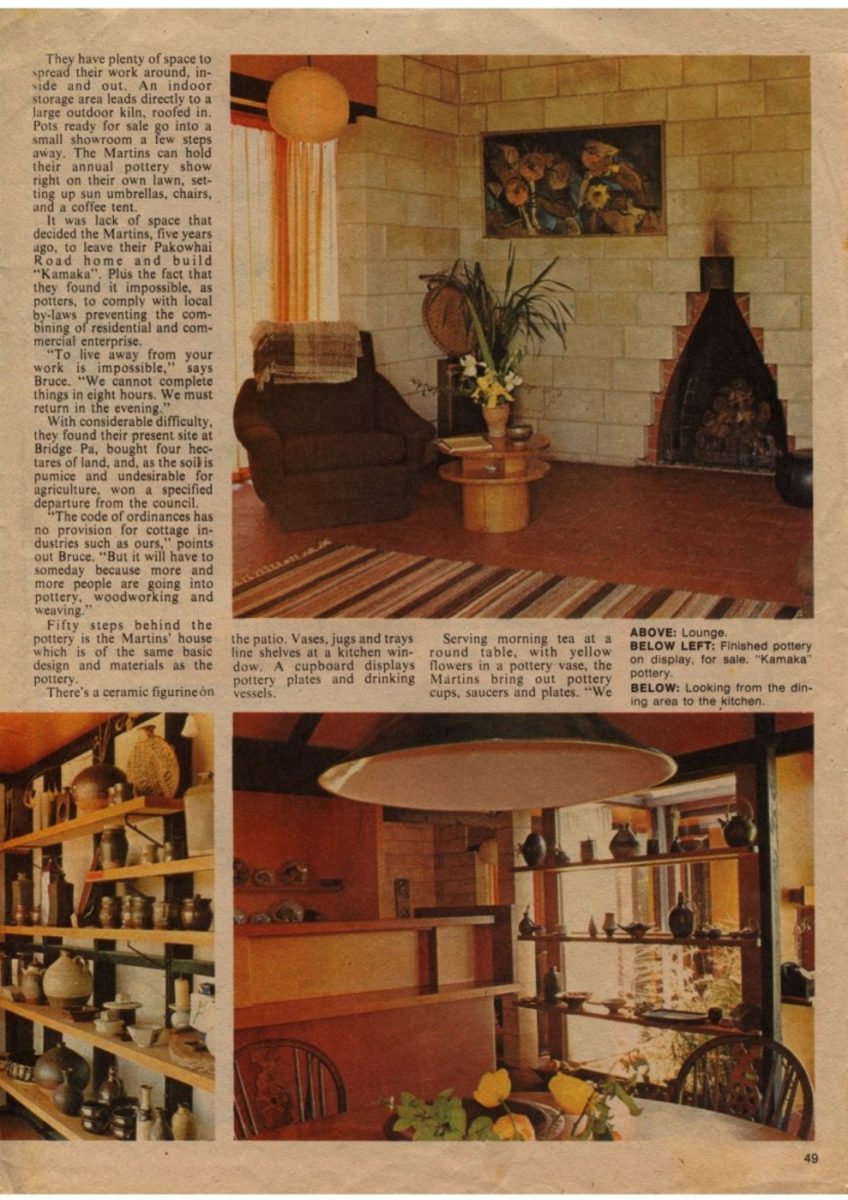

Open day at “Kamaka” – the public can walk around and see a potter’s dream place.

Boys lounge.

50

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.